A Review of Microplastics Research in the Shipbuilding and Maritime Transport Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

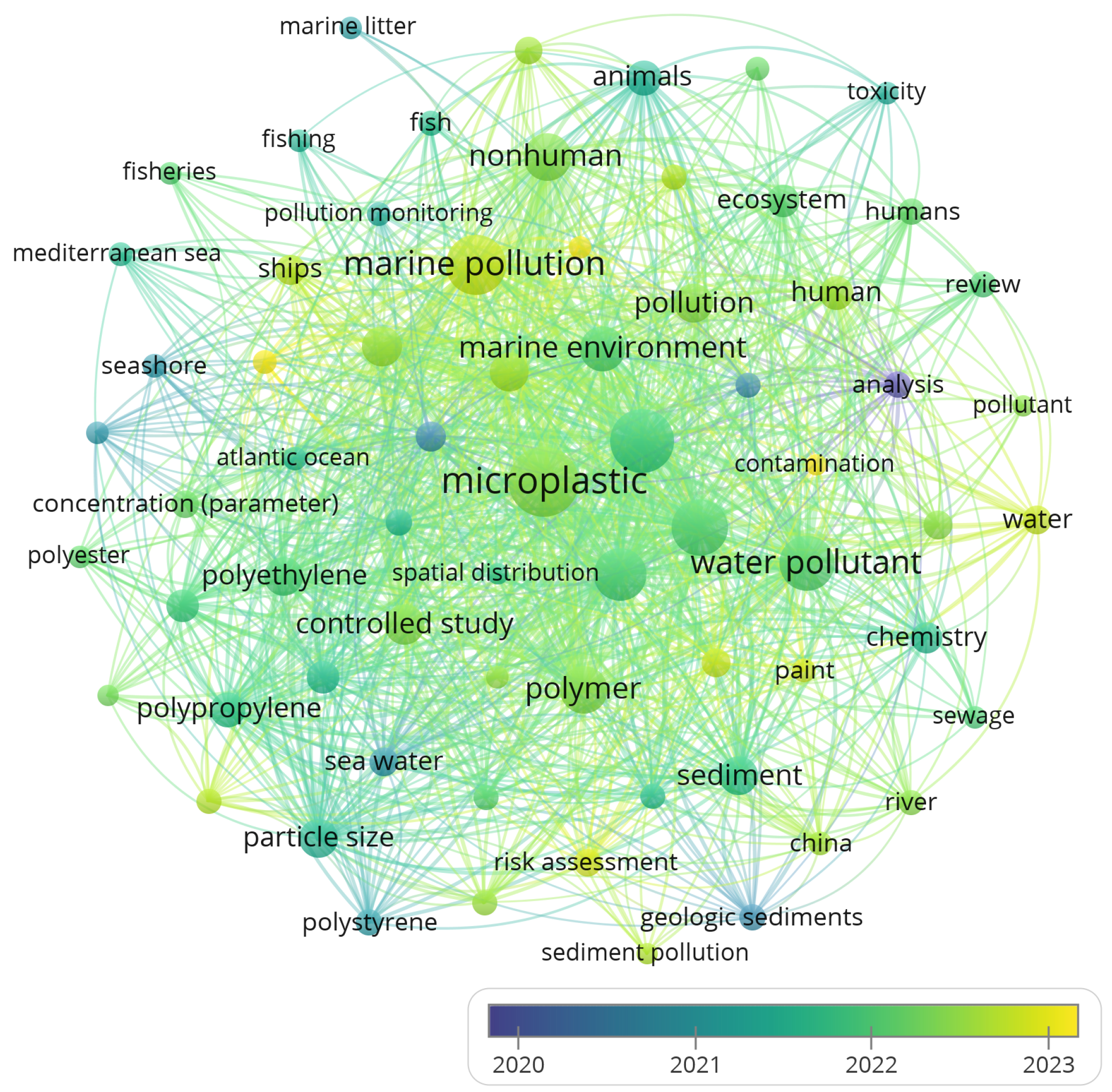

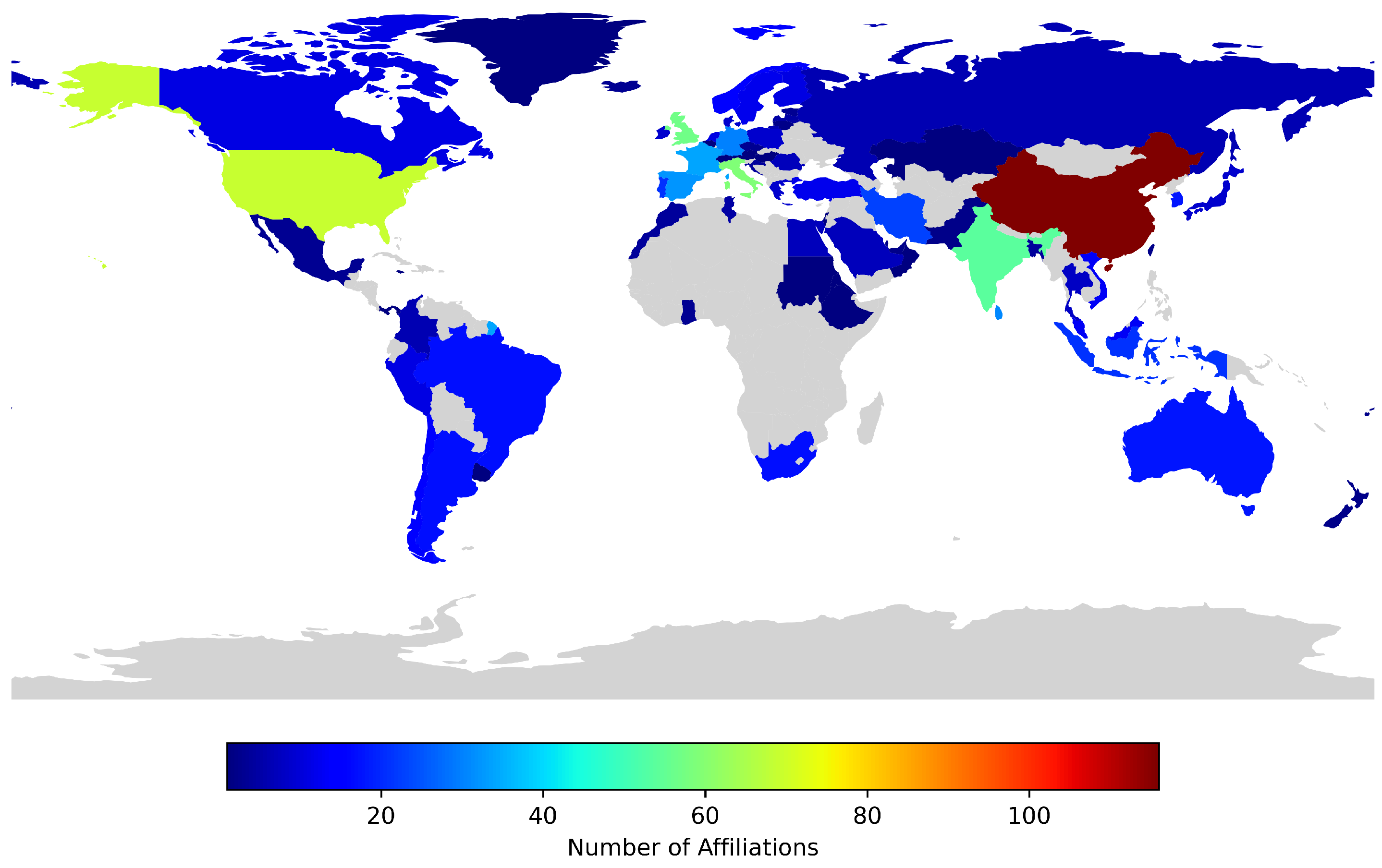

2. Materials and Methods

3. Measurement and Modeling of Microplastic Pollution in the Sea

4. Sources and Vectors of MP-Related Pollution in Maritime Transport

4.1. Paint Erosion During Vessel Operation

4.2. Gray Water

4.3. Ballast Water

5. Sources of MP-Related Pollution in Shipyards

5.1. Antifouling Paint

5.2. Plastic Piping Fabrication Debris

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Graywater treatment procedures demonstrate significant potential to reduce the release of MP particles into the marine environment. The available evidence indicates that passenger ships require particular attention due to their comparatively higher MP emissions.

- Reported MP concentrations in ballast water vary substantially across studies. Due to the lack of information on ballast water origin and the limited number of studies, no general conclusions can currently be drawn. Nevertheless, emerging treatment approaches show promise for capturing MP particles.

- Existing estimates of plastic and MP releases from vessel operation and maintenance activities indicate potentially concerning emission levels; however, direct measurements remain limited, highlighting the need for more comprehensive investigation.

- Manufacturing procedures that minimize plastic debris generation should be investigated, alongside operational strategies to prevent debris from entering marine environments.

- Gray water research should encompass a wider variety of vessels with varying passenger capacities to determine true MP contributions. A comprehensive analysis of both treated and untreated wastewater samples is needed to identify effective treatment strategies for MP reduction.

- Studies investigating ballast water should explore how the geographic source of ballast water influences MP contamination, using larger sample sizes to establish reliable trends.

- Standardized methodologies for quantifying MP emissions from different maintenance operations should be established to enable accurate assessment based on the maintenance operation.

- Standardized methodologies for measuring MP concentrations are needed to enable reliable assessment and comparison of emerging filtration techniques and other treatment technologies for MP removal.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Directive 2005/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on Ship-Source Pollution and On the Introduction of Penalties for Infringements. 2005. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2005/35/oj/eng (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2019/883 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on Port Reception Facilities for the Delivery of Waste From Ships. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/883/oj (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Gesamp, G. Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment: Part two of a global assessment. IMO Lond. 2016, 220, 1–221. [Google Scholar]

- Schernewski, G.; Radtke, H.; Hauk, R.; Baresel, C.; Olshammar, M.; Osinski, R.; Oberbeckmann, S. Transport and behavior of microplastics emissions from urban sources in the Baltic Sea. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 579361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Yu, K.; Wang, S. Underestimated microplastic pollution derived from fishery activities and “hidden” in deep sediment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 2210–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apete, L.; Martin, O.V.; Iacovidou, E. Fishing plastic waste: Knowns and known unknowns. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 205, 116530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Court of Auditors. Special report 06/2025: EU Actions Tackling Sea Pollution by Ships—Not Yet Out of Troubled Waters. 2025. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications/SR-2025-06 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Karlsson, T.M.; Arneborg, L.; Broström, G.; Almroth, B.C.; Gipperth, L.; Hassellöv, M. The unaccountability case of plastic pellet pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Preventing Plastic Pellet Losses to Reduce Microplastic Pollution. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52023PC0645 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Koelmans, A.A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Nor, N.H.M.; de Ruijter, V.N.; Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; Da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, K.; Green, D. The potential effects of microplastics on human health: What is known and what is unknown. Ambio 2022, 51, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graca, B.; Szewc, K.; Zakrzewska, D.; Dołęga, A.; Szczerbowska-Boruchowska, M. Sources and fate of microplastics in marine and beach sediments of the Southern Baltic Sea—A preliminary study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7650–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belioka, M.P.; Achilias, D.S. Microplastic pollution and monitoring in seawater and harbor environments: A meta-analysis and review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supe Tulcan, R.X.; Lu, X. Microplastics in ports worldwide: Environmental concerns or overestimated pollution levels? Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 1803–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yanai, H.; Yap, C.K.; Emmanouil, C.; Okamura, H. Anthropogenic microparticles in sea-surface microlayer in Osaka Bay, Japan. J. Xenobiotics 2023, 13, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Suzuki, T.; Viyakarn, V.; Hagita, R.; Joshima, H.; Arakawa, H. Pollution, degradation, and risk assessment of microplastic (>30 μm) in subsurface (5 m) seawaters along Tokyo-Bangkok shipping route. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 998, 180261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Iglesias, L.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Á.; Fernández, S.; Casement, E.; Menéndez-Teleña, D.; Carrera-Rodríguez, I.; Dopico, E.; Soto-López, V.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Citizen science study on maritime traffic and plastic debris in Asturias estuaries. J. Mar. Syst. 2025, 252, 104153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, C.; Awe, A. Concentrations and risk assessment of metals and microplastics from antifouling paint particles in the coastal sediment of a marina in Simon’s Town, South Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 59996–60011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islas, M.S.; Díaz-Jaramillo, M.; Pegoraro, C.; Sliba, A.M.; Gonzalez, M. Spatio-temporal characterization of paint-related debris as a source of metals in high maritime traffic and maintenance areas from the SW Atlantic coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2026, 223, 119016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuan, P.M.; Nguyen, M.K.; Nguyen, D.D. The potential release of microplastics from paint fragments: Characterizing sources, occurrence and ecological impacts. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburri, M.N.; Davidson, I.C.; First, M.R.; Scianni, C.; Newcomer, K.; Inglis, G.J.; Georgiades, E.T.; Barnes, J.M.; Ruiz, G.M. In-water cleaning and capture to remove ship biofouling: An initial evaluation of efficacy and environmental safety. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, Z.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Yoon, C.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, M. Characterization of hazards and environmental risks of wastewater effluents from ship hull cleaning by hydroblasting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, Z.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Loh, A.; Yoon, C.; Shin, D.; Kim, M. Seawater contamination associated with in-water cleaning of ship hulls and the potential risk to the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, Z.Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, M. Metals and suspended solids in the effluents from in-water hull cleaning by remotely operated vehicle (ROV): Concentrations and release rates into the marine environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Park, J.G.; Kang, H.M.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.W. Toxic effects of the wastewater produced by underwater hull cleaning equipment on the copepod Tigriopus japonicus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Javed, A.; Kim, T.; Shim, W.J.; Kim, M. Effect-directed analysis of hazardous organic chemicals released from ship hull hydroblasting effluents and their emission to marine environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oertel, G.; Vaagen, H.; Glavee-Geo, R. Identifying and managing ship paint microplastic pollution along the supply chain: A shipbuilding case study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 218, 118182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.K.; Naik, M.M.; D’Costa, P.M.; Shaikh, F. Microplastics in ballast water as an emerging source and vector for harmful chemicals, antibiotics, metals, bacterial pathogens and HAB species: A potential risk to the marine environment and human health. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L.; Dekker, R.; Van Den Berg, J. A comparison of two techniques for bibliometric mapping: Multidimensional scaling and VOS. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 2405–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.B.; Huffer, T.; Thompson, R.C.; Hassellov, M.; Verschoor, A.; Daugaard, A.E.; Rist, S.; Karlsson, T.; Brennholt, N.; Cole, M.; et al. Are we speaking the same language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Recommendations for Quantifying Synthetic Particles in Waters and Sediments. 2015. Available online: https://ikhapp.org/all-publications/laboratory-methods-for-the-analysis-of-microplastics-inthe-marine-environment-recommendations-for-quantifying-synthetic-particles-inwaters-and-sediments/ (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Chae, B.; Oh, S.; Lee, D.G. Is 5 mm still a good upper size boundary for microplastics in aquatic environments? Perspectives on size distribution and toxicological effects. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Transport of microplastics in coastal seas. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 199, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Maity, J.P.; Singha, S.; Mishra, T.; Dey, G.; Samal, A.C.; Banerjee, P.; Biswas, C.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Patra, R.R.; et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in environment: Sampling, characterization and analytical methods. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 26, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N.; Safhi, A.E.M.; Laissaoui, A. Insightful analytical review of potential impacts of microplastic pollution on coastal and marine ecosystem services. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, C.; Yin, J.; Ding, J.; Cao, W.; Fan, W. Overview of monitoring methods and environmental distribution: Microplastics in the Indian Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 214, 117715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fytianos, G.; Ioannidou, E.; Thysiadou, A.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. Microplastics in Mediterranean coastal countries: A recent overview. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, P.P.; Pan, K.; Krishnan, J.N. Microplastics: Global occurrence, impact, characteristics and sorting. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 893641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Rasaq, M.F.; Omotoye, E.V.; Araomo, O.V.; Adekoya, O.S.; Abolaji, O.Y.; Hungbo, J.J. Microplastics in freshwater and marine ecosystems: Occurrence, characterization, sources, distribution dynamics, fate, transport processes, potential mitigation strategies, and policy interventions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, V.; Litti, L.; Lavagnolo, M.C. Microplastic pollution in the North-east Atlantic Ocean surface water: How the sampling approach influences the extent of the issue. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, F.; Kochleus, C.; Bänsch-Baltruschat, B.; Brennholt, N.; Reifferscheid, G. Sampling techniques and preparation methods for microplastic analyses in the aquatic environment—A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 113, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesamp, G. Guidelines for the monitoring and assessment of plastic litter in the ocean. J. Ser. GESAMP Rep. Stud. 2019, 99, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenfeld, N.; Arbuckle-Keil, G.; Beni, N.N.; Bartelt-Hunt, S.L. Source tracking microplastics in the freshwater environment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 112, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Li, Y.; Lu, N.; Qu, L.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Y.; Lu, D.; Han, J.; Han, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Abundance, characteristics and ecological risk assessment of microplastics in ship ballast water in ports around Liaodong Peninsula, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 207, 116812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, T.; Abunama, T.; Kumari, S.; Amoah, D.; Seyam, M. Applications of mathematical modelling for assessing microplastic transport and fate in water environments: A comparative review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senathirajah, K.; Pattiaratchi, C. Microplastics in bays: Transport processes and numerical models. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 993, 179995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, F.G.; De-la Torre, G.E. Environmental pollution with antifouling paint particles: Distribution, ecotoxicology, and sustainable alternatives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A. Paint particles in the marine environment: An overlooked component of microplastics. Water Res. X 2021, 12, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, Z.T.; Chen, Y.; Rochman, C.M. Paint: A ubiquitous yet disregarded piece of the microplastics puzzle. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2025, 44, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburri, M.N.; Soon, Z.Y.; Scianni, C.; Øpstad, C.L.; Oxtoby, N.S.; Doran, S.; Drake, L.A. Understanding the potential release of microplastics from coatings used on commercial ships. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1074654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistenschneider, C.; Burkhardt-Holm, P.; Mani, T.; Primpke, S.; Taubner, H.; Gerdts, G. Microplastics in the Weddell Sea (Antarctica): A forensic approach for discrimination between environmental and vessel-induced microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 15900–15911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero-López, A.D.; Colombo, C.V.; Loperena, A.P.; Morales-Pontet, N.G.; Ronda, A.C.; Lehr, I.L.; De-la Torre, G.E.; Ben-Haddad, M.; Aragaw, T.; Suaria, G.; et al. Paint particle pollution in aquatic environments: Current advances and analytical challenges. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, M.; Kiil, S.; Gostin, P.F.; Dam-Johansen, K. Characterization of microplastics from antifouling coatings released under controlled conditions with an automated SEM-EDX particle analysis method. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 386, 127251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwuzor, I.C.; Idumah, C.I.; Nwanonenyi, S.C.; Ezeani, O.E. Emerging trends in self-polishing anti-fouling coatings for marine environment. Saf. Extrem. Environ. 2021, 3, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Gao, G. Divergence to concentration and population to individual: A progressive approaching ship detection paradigm for synthetic aperture radar remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, E.; Gil-Solsona, R.; Mikkolainen, E.; Hytti, M.; Ytreberg, E.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Petrović, M.; Gros, M. Identification of emerging contaminants in greywater emitted from ships by a comprehensive LC-HRMS target and suspect screening approach. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujingni, J.; Ytreberg, E.; Hassellöv, I.M.; Rathnamali, G.; Hassellöv, M.; Salo, K. Sampling strategy, quantification, characterization and hazard potential assessment of greywater from ships in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 208, 116993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Schyff, V.; Stiborek, M.; Šimek, Z.; Vrana, B.; Meraldi, V.; King, A.L.; Melymuk, L. Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals and Other Anthropogenic Compounds in the Wastewater Effluent of Arctic Expedition Cruise Ships. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Xu, B.; Li, D. Gray water from ships: A significant sea-based source of microplastics? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folbert, M.E.; Corbin, C.; Löhr, A.J. Sources and leakages of microplastics in cruise ship wastewater. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 900047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, R.; Lu, D. Research status and prospect of microplastics in ship grey water. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Sustainable Development and Energy Resources (SDER 2024), Chongqing, China, 9 August–11 August 2024; Volume 573, p. 01019. [Google Scholar]

- Kalnina, R.; Demjanenko, I.; Smilgainis, K.; Lukins, K.; Bankovics, A.; Drunka, R. Microplastics in ship sewage and solutions to limit their spread: A case study. Water 2022, 14, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.L.; Jeong, J.; Eo, S.; Hong, S.H.; Shim, W.J. Occurrence and characteristics of microplastics in greywater from a research vessel. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 341, 122941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Su, Q.; Li, Y.; Qu, L.; Kong, L.; Cheng, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, J.; Han, J.; Wang, X. Characterization of microplastic distribution, sources and potential ecological risk assessment of domestic sewage from ships. Environ. Res. 2025, 268, 120755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, S.B.; Pambudi, D.S.A.; Ahmad, M.M.; Alfanda, B.D.; Imron, M.F.; Abdullah, S.R.S. Ecological impacts of ballast water loading and discharge: Insight into the toxicity and accumulation of disinfection by-products. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiddi, M.; Tornambè, A.; Silvestri, C.; Cicero, A.; Magaletti, E. First evidence of microplastics in the ballast water of commercial ships. In Proceedings of the MICRO 2016, Lanzarote, Spain, 25 May–27 May 2016; pp. 136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Zendehboudi, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Dobaradaran, S.; De-la Torre, G.E.; Ramavandi, B.; Hashemi, S.E.; Saeedi, R.; Tayebi, E.M.; Vafaee, A.; Darabi, A. Analysis of microplastics in ships ballast water and its ecological risk assessment studies from the Persian Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalnina, R.; Andze, L. Microplastics in Ballast Water and Limiting Movement in the Global Aquatic Environment: A Case Study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 221, 118538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, R.K.; Chakraborty, P.; D’Costa, P.M.; Mishra, R.; Fernandes, V. A simple technique to mitigate microplastic pollution and its mobility (via ballast water) in the global ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 283, 117070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Sector Performance Report. Shipbuilding & Ship Repair. 2008. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/sectors/web/pdf/shipbuilding.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- López, M.; Lilao, A.L.; Ribalta, C.; Martínez, Y.; Piña, N.; Ballesteros, A.; Fito, C.; Koehler, K.; Newton, A.; Monfort, E.; et al. Particle release from refit operations in shipyards: Exposure, toxicity and environmental implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Grythe, H.; Klimont, Z.; Heyes, C.; Eckhardt, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Stohl, A. Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Verla, A.W.; Verla, E.N.; Ibe, F.C.; Amaobi, C.E. Airborne microplastics: A review study on method for analysis, occurrence, movement and risks. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, Z.Y.; Tamburri, M.N.; Kim, T.; Kim, M. Estimating total microplastic loads to the marine environment as a result of ship biofouling in-water cleaning. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1502000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Eo, S.; Shim, W.J.; Kim, M. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of microplastics derived from antifouling paint in effluent from ship hull hydroblasting and their emission into the marine environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la Torre, G.E.; Dioses-Salinas, D.C.; Dobaradaran, S. A perspective on the methodological challenges in the emerging field of antifouling paint particles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 65884–65888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghilinejad, M.; Kabir-Mokamelkhah, E.; Nassiri-Kashani, M.H.; Bahrami-Ahmadi, A.; Dehghani, A. Assessment of pulmonary function parameters and respiratory symptoms in shipyard workers of Asaluyeh city, Iran. Tanaffos 2016, 15, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Lučin, B.; Čarija, Z.; Alvir, M.; Lučin, I. Strategies for green shipbuilding design and production practices focused on reducing microplastic pollution generated during installation of plastic pipes. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Al Amin, M.; Gibson, C.T.; Chuah, C.; Tang, Y.; Naidu, R.; Fang, C. Raman imaging of microplastics and nanoplastics generated by cutting PVC pipe. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298, 118857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaway, A.M.N.; Rajput, R.; Mohan, G.; Katsuma, Y.; Pu, J. A systematic review of microplastics perception and its factors: Implications on SDGs. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 10, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Eo, S.; Shim, W.J.; Kim, M. Characterization of ship paint-derived microplastics by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and density analyses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Sewage Type | Average Concentration (n/L) | Pore Size (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalnina et al. [63] | Gray water | 71 | 0.7 |

| Treated gray and black water | 51 | ||

| Jang et al. [64] | Laundry gray water | 177 | 10 |

| Cabins gray water | 133 | ||

| Galley gray water | 75 | ||

| Lu et al. [65] | Gray water | 167 | 0.7 |

| Black water | 36.96 | ||

| Mixed domestic sewage | 46.57 | ||

| Passanger ships | 57.2 | ||

| Oil tankers | 44.4 | ||

| Unprocessed domestic sewage | 87.43 | ||

| Processed domestic sewage | 40.96 | ||

| Average value | 50.82 |

| Source | Ref. | Focus | Contribution | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray water | [63] | 50 gray water and treated sewage samples from 5 transport ships | Quantified MP treatment reduction | Limited vessel count |

| [64] | Galley, cabin, laundry tanks on research vessel | MP quantification by source type | Single-vessel study | |

| [65] | Gray and black water from 33 vessels | Compared treated vs untreated water across vessel types | Unbalanced sampling |

| Reference | Number and Type of Vessel | Average Concentration (n/L) | Filtration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matiddi et al. [67] | 9 cargo ships | 0.651 ± 0.160 | 50 m (mesh aperture diameter) |

| Zendehboudi et al. [68] | 30 ships | 12.53 ± 4.85 | 0.45 m (pore size) |

| Su et al. [45] | 13 transport ships | 6.07 ± 1.3 | 0.7 m (pore size) |

| Kalnina and Andze [69] | 5 tankers | 26 | 0.7m (pore size) |

| Vector | Ref. | Focus | Contribution | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballast water | [67] | MP in ballast water of 9 cargo vessels | First ballast water MP study | No size/polymer data |

| [68] | 6 seawater and 30 ballast water samples from vessels | Baseline comparison | Source impact unclear | |

| [45] | 13 transport vessels at 5 sites | Considered vessels on international and domestic routes | Small subgroup sizes | |

| [69] | 5 tankers with samples collected in different regions | Proposed novel technical solution | Efficiency not evaluated |

| Ref. | Activity | Global Plastic Fleet Emission Estimation (Tons/Year) | Pore Size (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soon et al. [75] | Manual in-water cleaning by divers | 2319 to 13,481 | 0.2 |

| ROV-based system without capture | 295 to 1183 | ||

| ROV-based system with capture and debris processing | 68 to 302 | ||

| Kim et al. [76] | Hydroblasting | 665.6 (MP 550.2) | 10 |

| Source | Ref. | Focus | Contribution | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP | [54] | MP emissions during simulated low-sailing conditions | Measured MP release from commercial coating | Single coating, reported methodological limits |

| [75] | MP emissions from diver and ROV brushing | Compared 2 cleaning techniques | MP estimation based on total suspended solids | |

| [76] | MP from hydroblasting | Quantification and characterization | Single case study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lučin, I.; Sikirica, A.; Lučin, B.; Alvir, M. A Review of Microplastics Research in the Shipbuilding and Maritime Transport Industry. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010073

Lučin I, Sikirica A, Lučin B, Alvir M. A Review of Microplastics Research in the Shipbuilding and Maritime Transport Industry. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleLučin, Ivana, Ante Sikirica, Bože Lučin, and Marta Alvir. 2026. "A Review of Microplastics Research in the Shipbuilding and Maritime Transport Industry" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010073

APA StyleLučin, I., Sikirica, A., Lučin, B., & Alvir, M. (2026). A Review of Microplastics Research in the Shipbuilding and Maritime Transport Industry. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010073