3.1. Genetic Algorithm Combined with Migration

In traditional genetic algorithms to solve path planning problems, the initial population is often generated randomly. It tends to produce initial populations with numerous redundant nodes and may even produce infeasible grids, especially when obstacles are large. To enhance the quality of population initialization, this paper adopts the following approach. First, excluding the rows containing the start and end points, a feasible grid is randomly selected in each row in ascending order. Combined with the start and end points, these selected grids form a node sequence for the path. Subsequently, the continuity between adjacent nodes in the sequence within the grid environment is evaluated on the following basis:

where

and

represent the coordinates of the corresponding node in the sequence. If the value of

O is one, it indicates that the adjacent nodes in the sequence are continuous. Otherwise, feasible nodes will be added to form an uninterrupted continuous path sequence. To this end, the following mean value interpolation method is employed.

where

is the node to be added; and

floor(·) denotes the floor function. In the case where

is an obstacle grid, feasible nodes around it should be selected. Through multiple iterations, a continuous sequence of path nodes is generated to complete the initialization of the population.

To enhance the overall fitness of the population, migration is performed. This operation enables different feasible solutions to share information so that inferior feasible solutions learn from superior ones. The immigration and emigration rates are calculated as follows [

17]:

where

is the immigration rate;

is the emigration rate;

I is the maximum possible immigration rate;

E is the maximum possible emigration rate; and

Smax is the largest possible number of species.

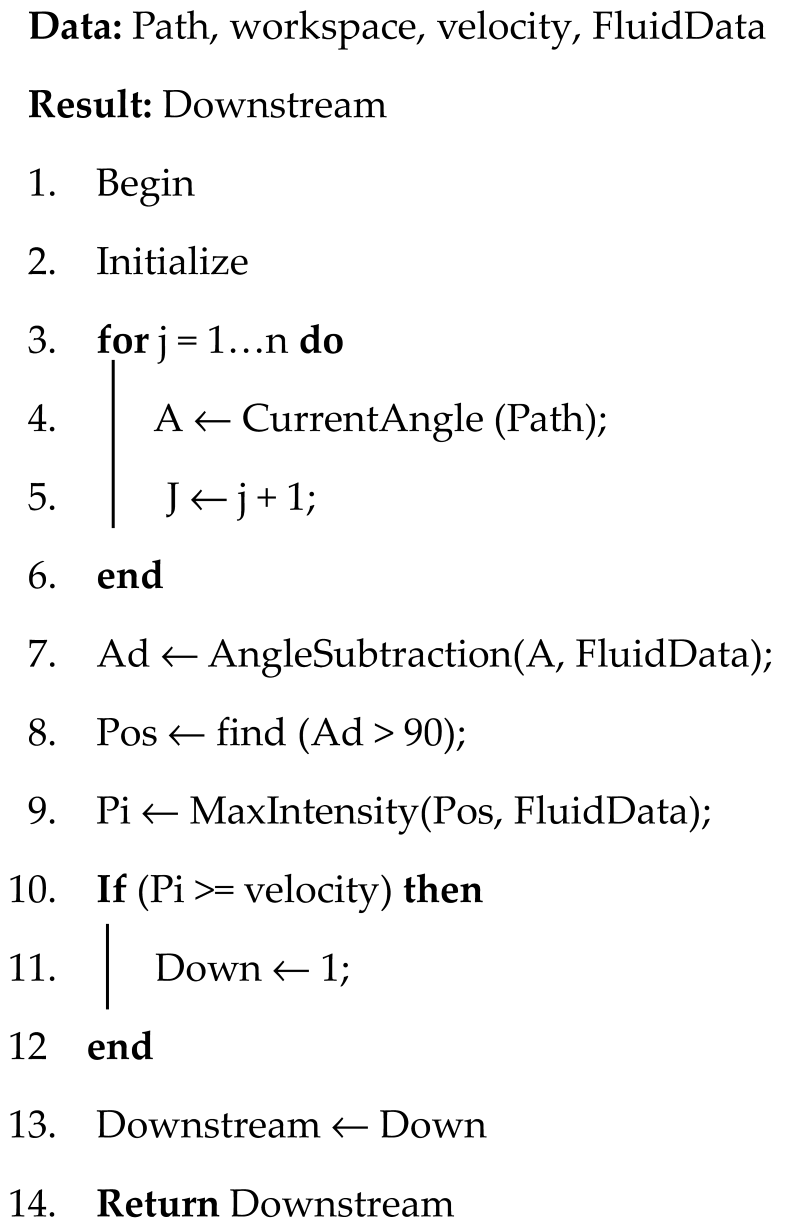

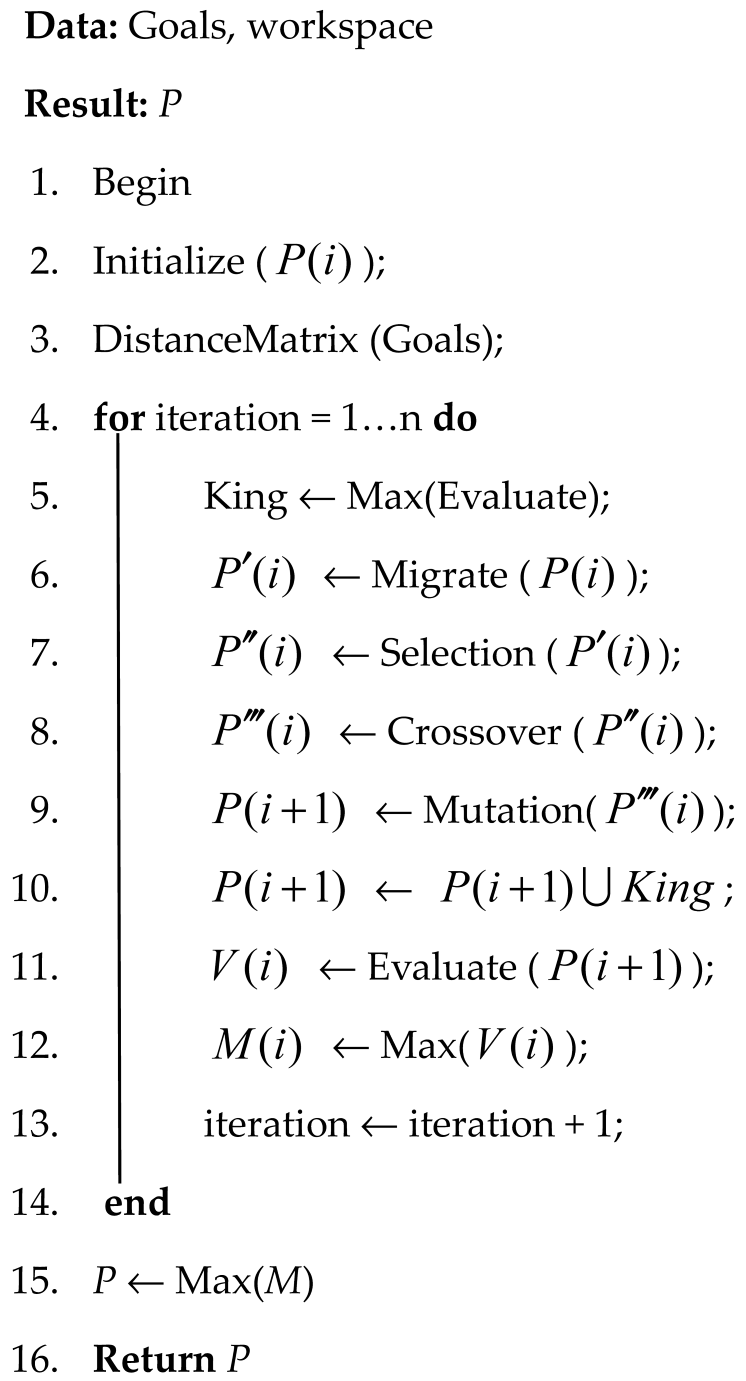

The pseudo-code of the proposed genetic algorithm combined with the migration (GAM) algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1. First, the initialization of population is performed. The obtained feasible solutions form a sequence of grid nodes. The fitness value of these feasible solutions is calculated by using a Euclidean distance-based evaluation function. Next, an elitist preservation strategy is employed. The feasible solution with the highest fitness value is selected and does not participate in subsequent operations. Afterwards, the migration operation is conducted to improve the fitness values of feasible solutions. The immigration and emigration rates are calculated and the paths for immigration and emigration are selected using the roulette wheel method. In the crossover stage, a random number within the range [0, 1] is generated to determine whether a crossover operation should be performed. The population is divided into three parts according to the fitness values and crossover is conducted within the same parts to reduce low-quality crossovers. First, all feasible solutions are ranked by their fitness values. Based on this ranking, they are categorized into three groups (good, medium, poor). Subsequently, within the same group, two feasible solutions are selected. A common node (excluding the start and end points) is randomly chosen as the crossover node to exchange their path segments. These solutions of intra-group crossover inherently impose a degree of constraint on the search direction. Compared to the traditional genetic algorithm, where two solutions are randomly selected from the entire population for crossover, our method substantially reduces the generation of low-quality offspring, thereby accelerating the convergence rate. Similar to the crossover operation, mutation is executed when the regenerated random number is less than the mutation probability. The population is sorted by fitness values. The top fifth is classified as elite solutions that do not undergo mutation, while the remaining solutions undergo mutation. Following the mutation stage, the fitness values of the population are updated and the optimal solution is recorded. When the maximum number of iterations has been reached, the iteration stops and the optimal path is obtained.

Traditional GA initializes paths through pure randomness, resulting in a low probability of feasible paths near large obstacles and computationally wasteful repair attempts. Our method overcomes this by directly generating a higher-quality initial population, requiring no repair. The design is two-fold: row-by-row progression provides macro-directional bias from start to goal, avoiding local traps; and in-row randomization preserves micro-level exploration as a form of constrained randomness. Path diversity will be further supplemented by subsequent migration, mutation, and crossover operations.

In Algorithm 1, Evaluate(

P(

i)) refers to the calculation of the fitness value for each path in the

i-th population generation using the path fitness function

E (Equation (5)). The evaluation criteria for the quality of a planned path generally involve multiple aspects such as path length and smoothness, which can be measured by a specific fitness function. In this paper, the primary research metric is the length of the planned path, while smoothness is taken as the secondary metric. As a path is composed of a sequence of nodes, the Euclidean distance is selected to determine the distance between two adjacent nodes. The path fitness function is defined as follows [

30]:

where

is the weight;

D is the Euclidean distance; and

S is the cost of path smoothness.

where

n is the number of nodes.

where

angle is the angle formed by three adjacent nodes, which can be calculated using the cosine theorem.

Migrate((

P(

i)) denotes the migration operation applied to the paths generated after the

i-th iteration;

where

is the new

k-th path after undergoing the migration operation;

is the function of the path generated; and

is the

j-th path as the migration path through roulette.

Selection(

P(

i)) represents the selection process for the paths produced in the

i-th generation. In this step, the probability of each individual being selected is computed based on its fitness value (higher fitness corresponds to a greater probability). These probabilities are summed to form a cumulative probability distribution over the interval [0, 1]. A random number is then generated, and the individual corresponding to the cumulative probability interval in which this number falls is selected. This process is repeated until the new population reaches the size of the original population, as shown below:

Crossover(

P(

i)) performs the crossover operation as follows: First, the population is sorted in descending order based on fitness and then divided into three groups. Within each group, two paths are randomly selected. It is then determined whether these two paths share any common points (excluding the start point and end point). Next, a random number

x between 0 and 1 is generated. If

x <

PC (predefined probability in crossover operation), a common point is randomly selected and crossover is performed at that point. If

x ≥ P

C, no crossover is applied. If the two paths do not share any common points (other than the start and end points), a segment from each path is randomly selected and joined together. If this process fails to produce a valid path after 100 attempts, the original paths are retained to avoid generating invalid solutions.

where

and

are the

i-th and

j-th paths within the same group, respectively; and

is the Cross-path generation function.

Mutation(

P(

i)) refers to the mutation operation applied to the paths generated in the

i-th iteration. First, all paths are sorted according to their fitness values. The top 1/5 of the paths are preserved without any mutation. For each of the remaining paths, a random number

y between 0 and 1 is generated. If

y <

Pm (predefined probability in mutation operation), a mutation operation—specifically, path segment replacement—is performed on that path; otherwise, no mutation is applied.

where

are the paths within the top fifth of the fitness values; and

is the function that path generated after mutating;

P(

i) denotes the path generated after the

i-th iteration, while

P denotes the path with the highest fitness value after 50 iterations.

| Algorithm 1: GAM |

![Jmse 14 00074 i001 Jmse 14 00074 i001]() |

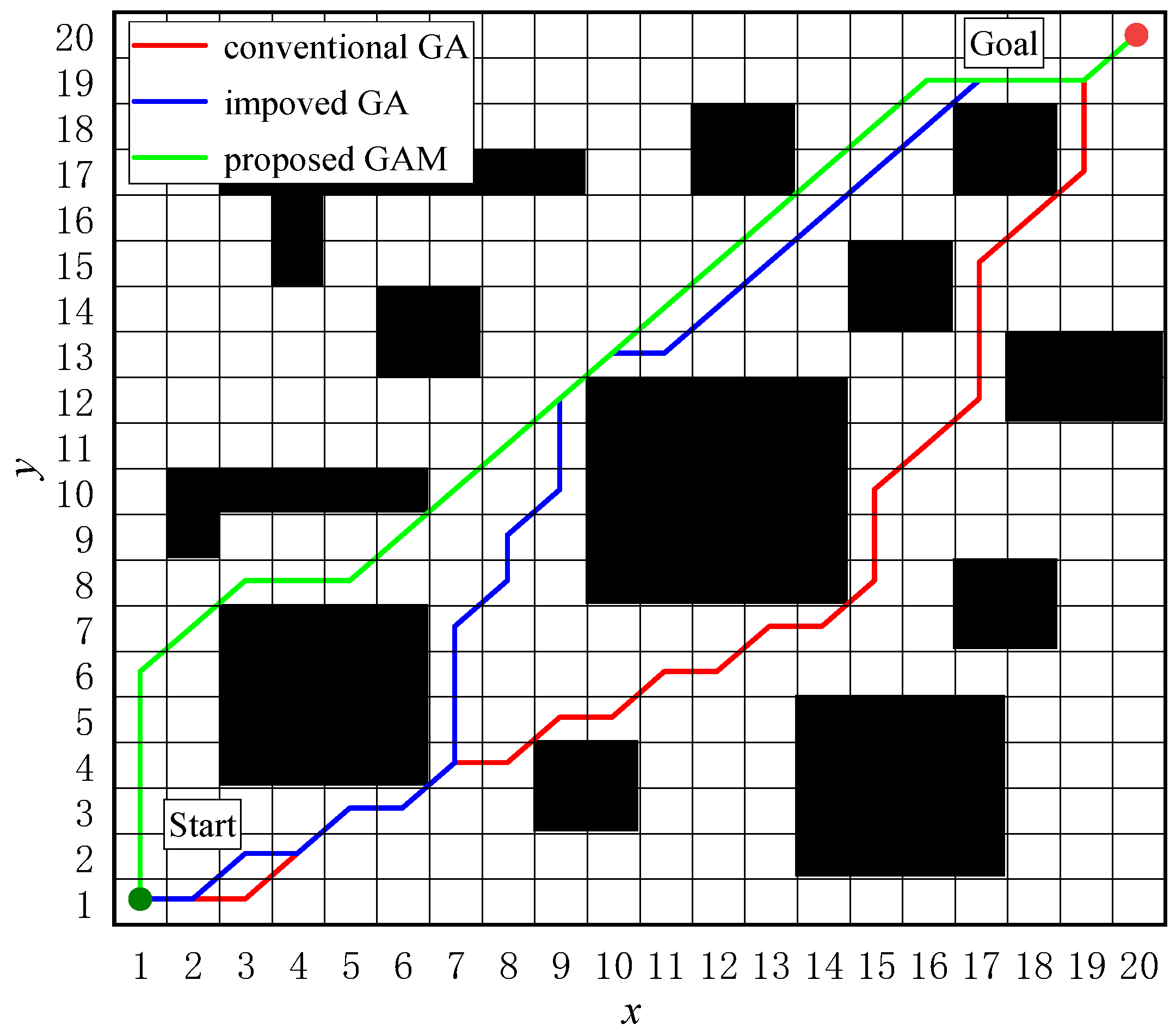

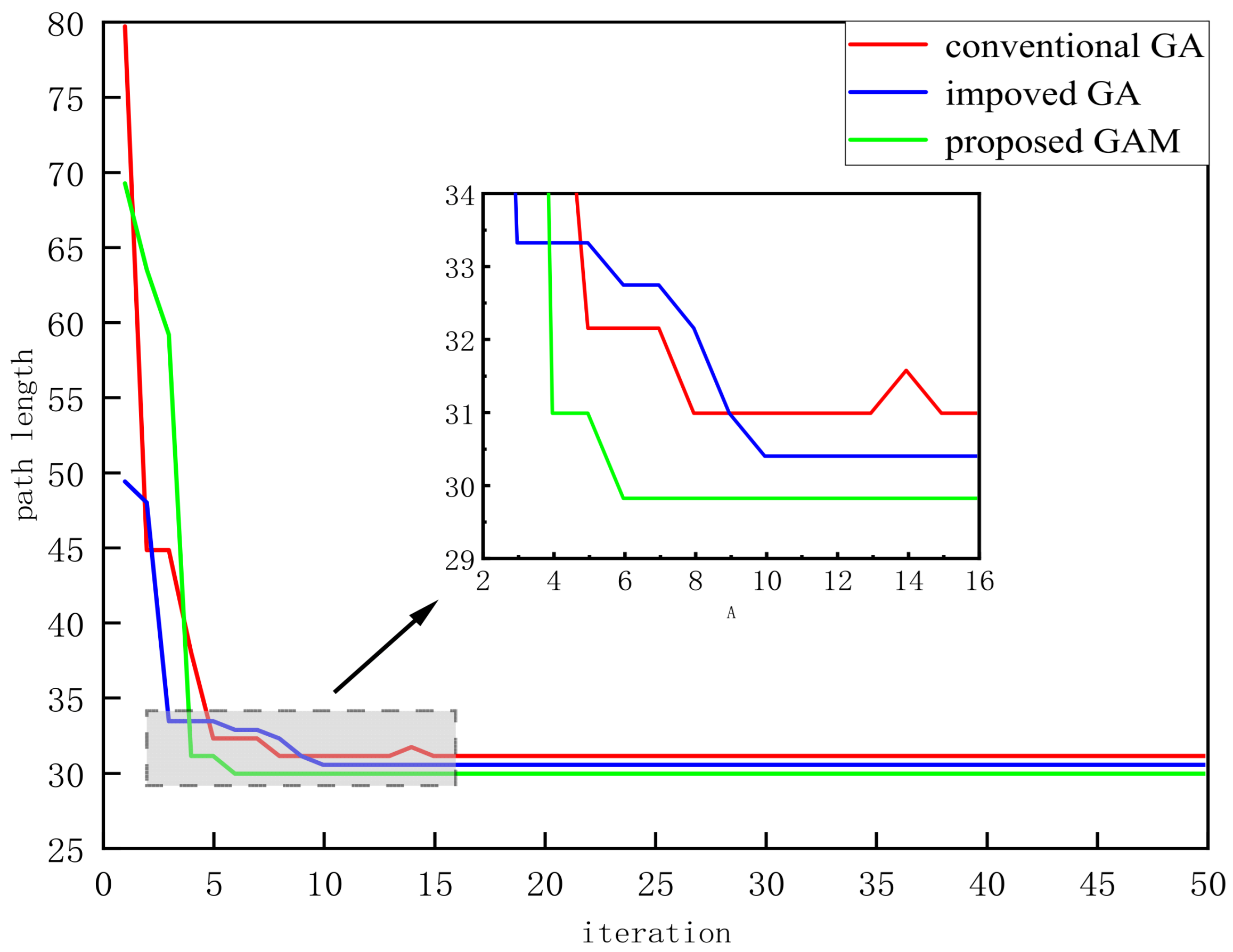

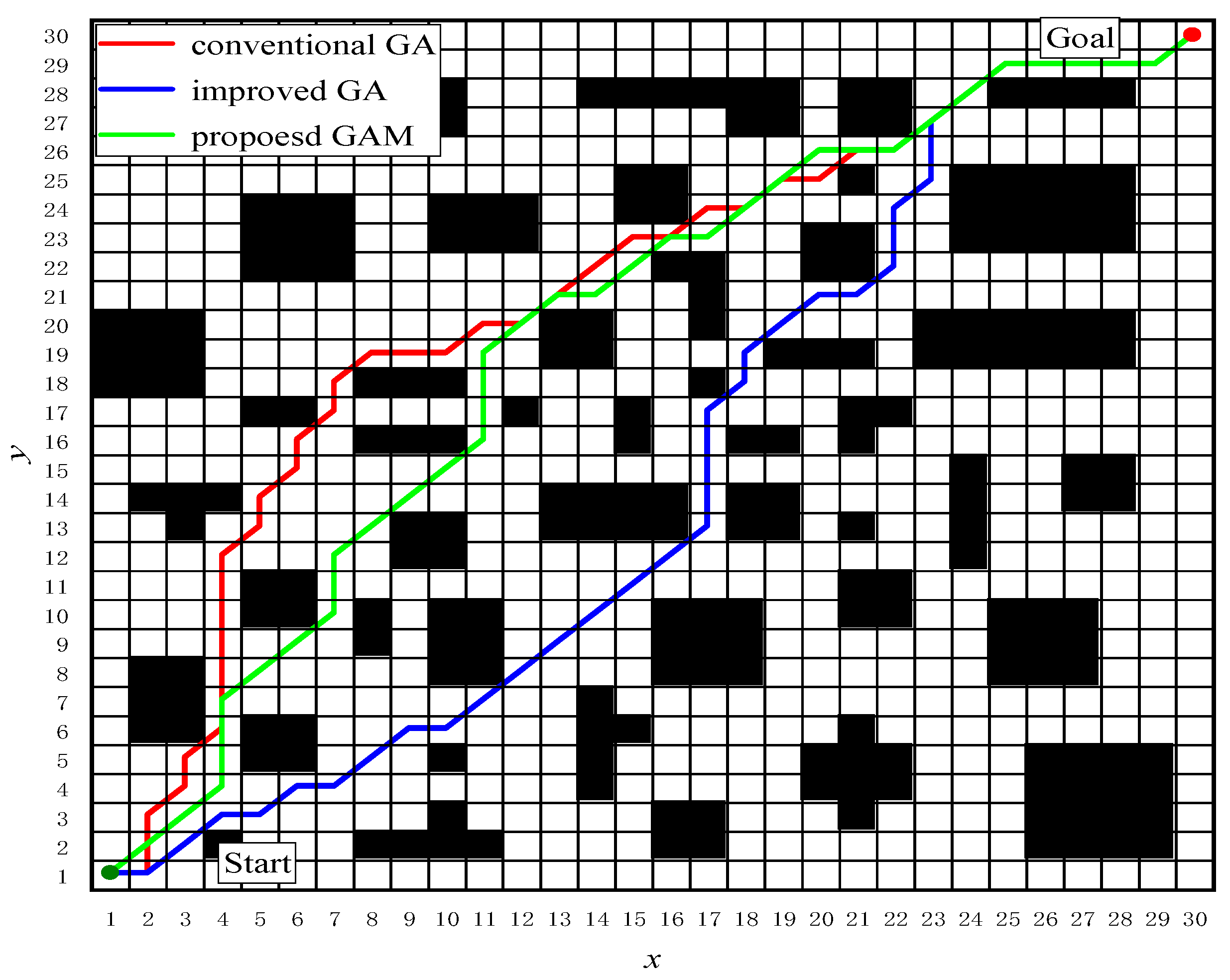

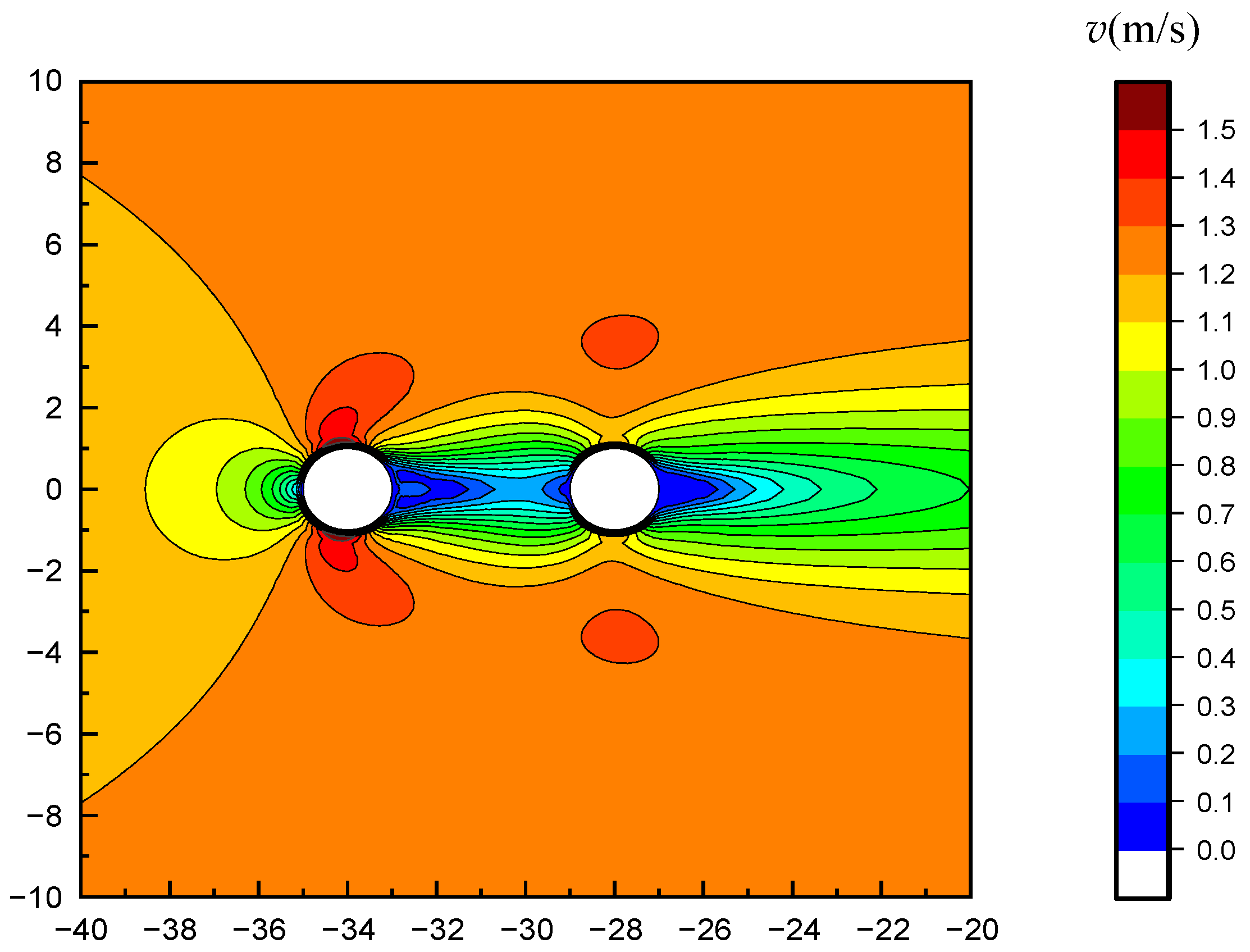

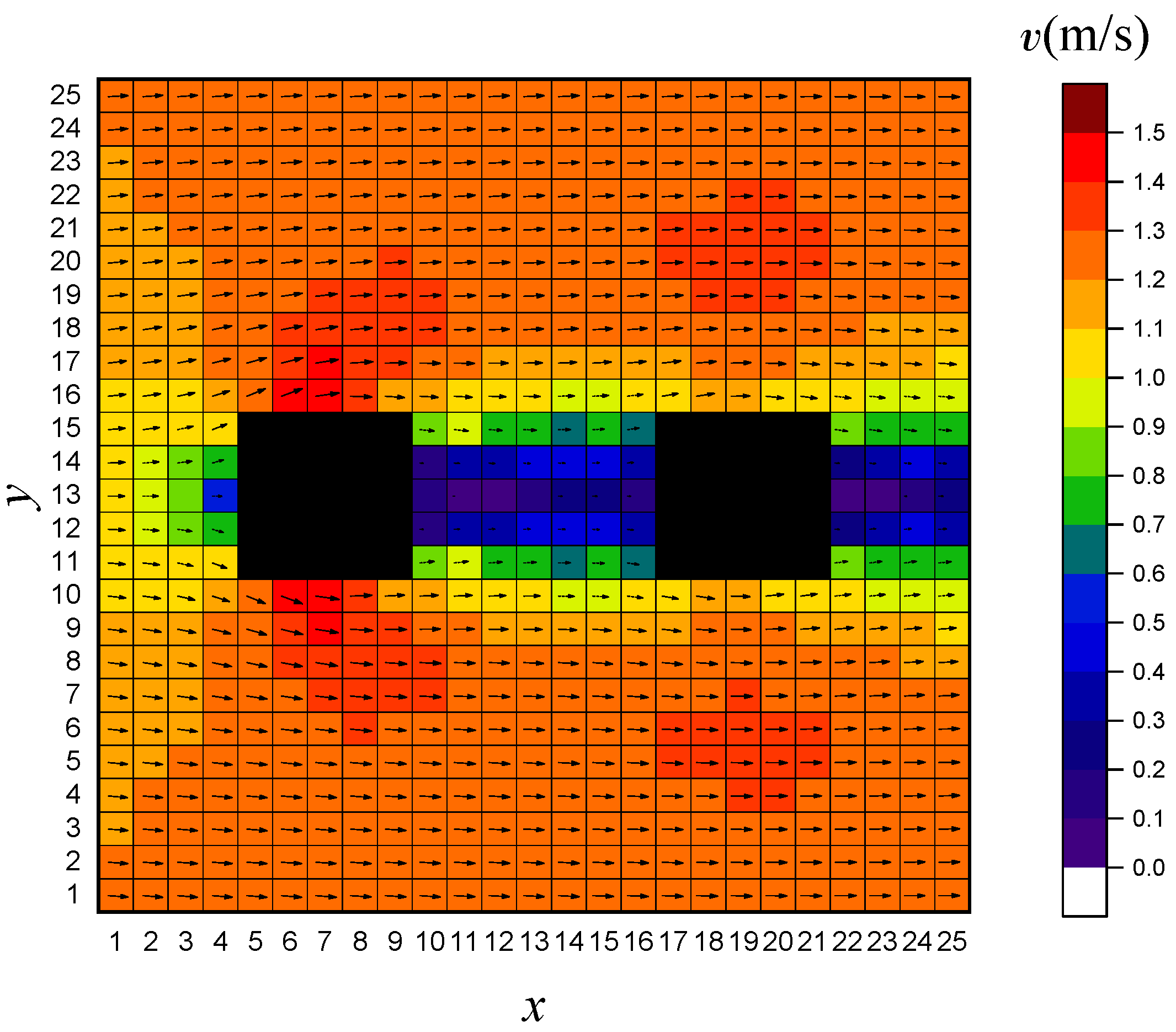

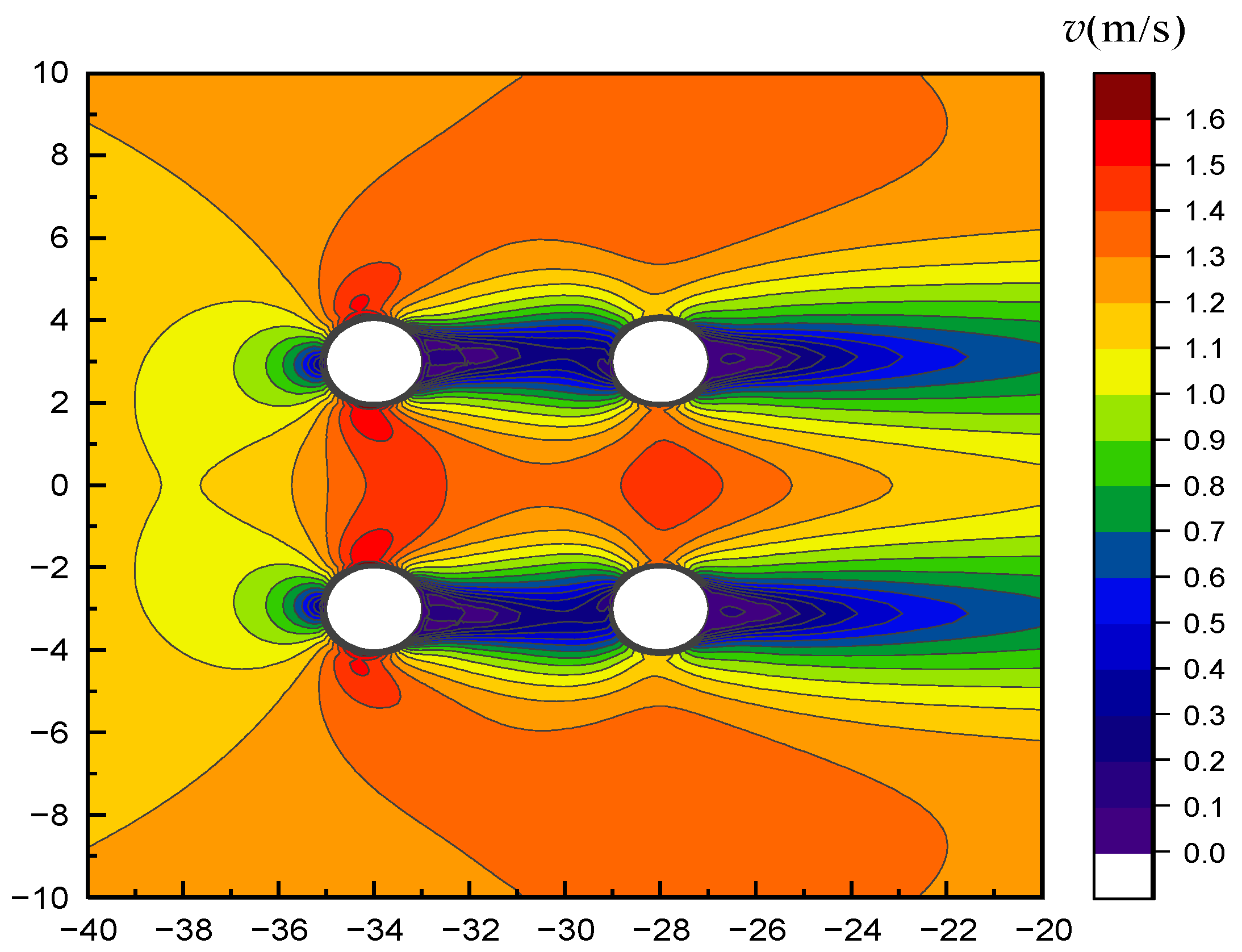

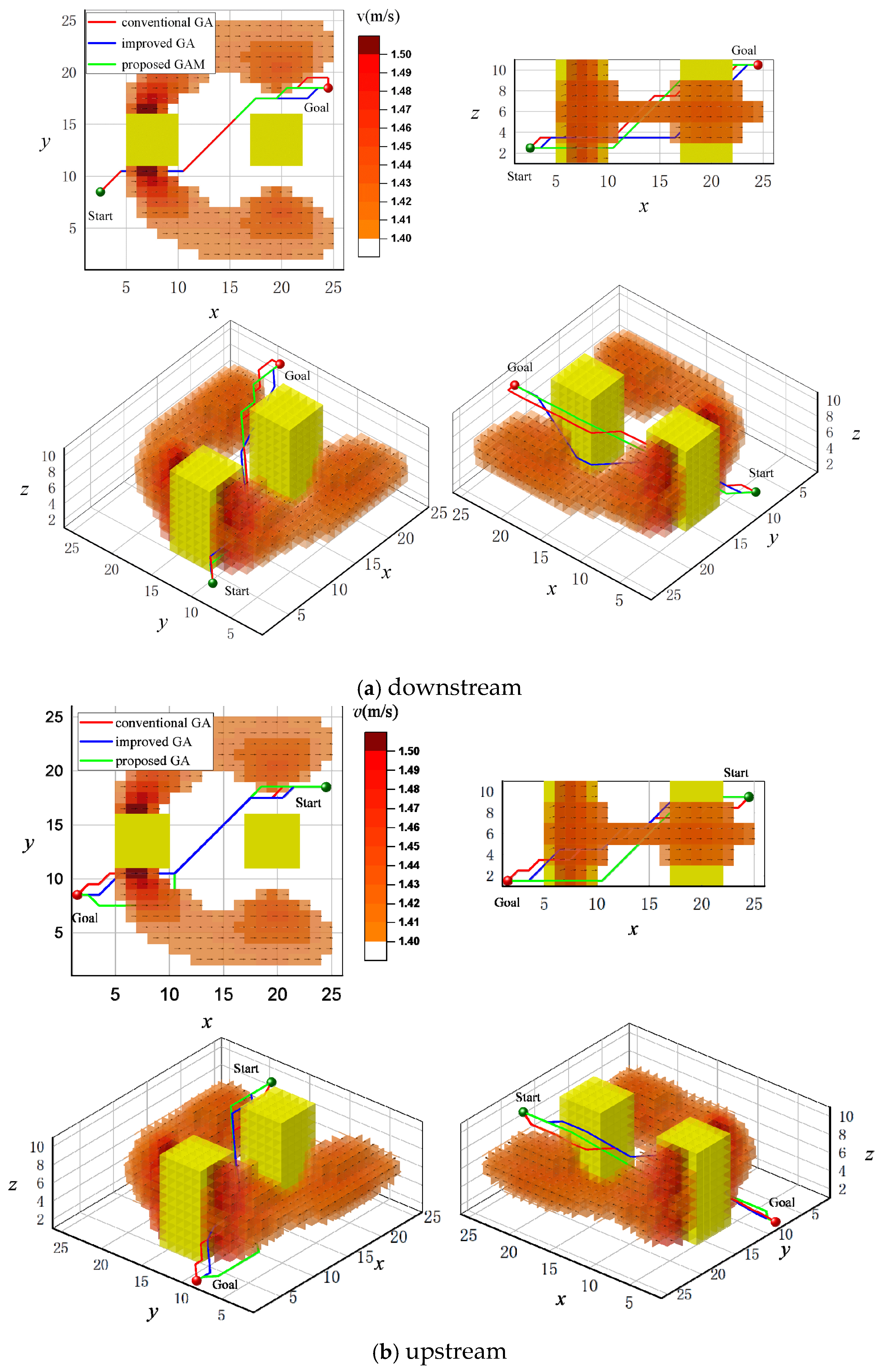

This paper conducted a comparative study of the GAM algorithm against both the traditional GA and an improved GA on 20 × 20 and 30 × 30 grid maps.

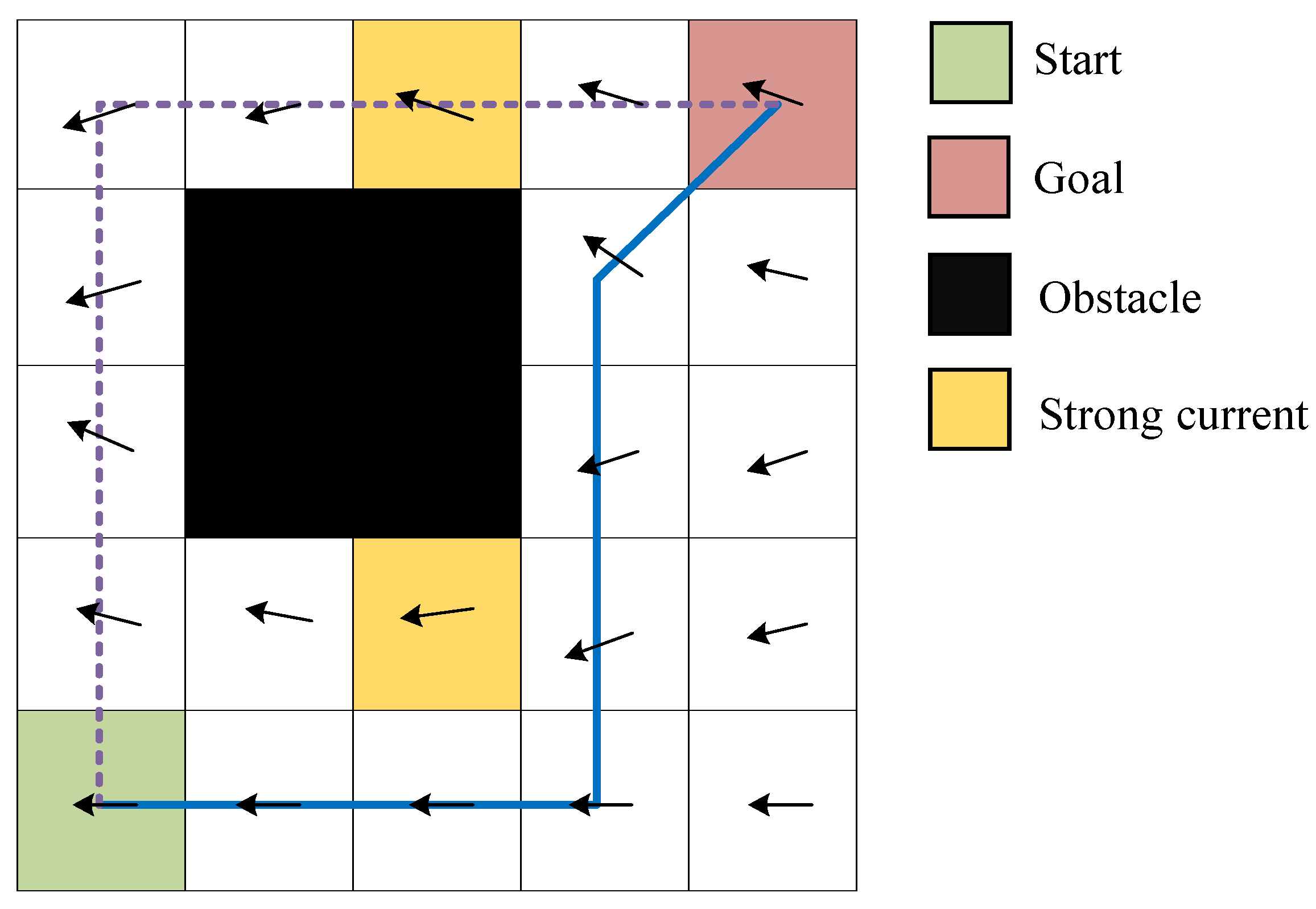

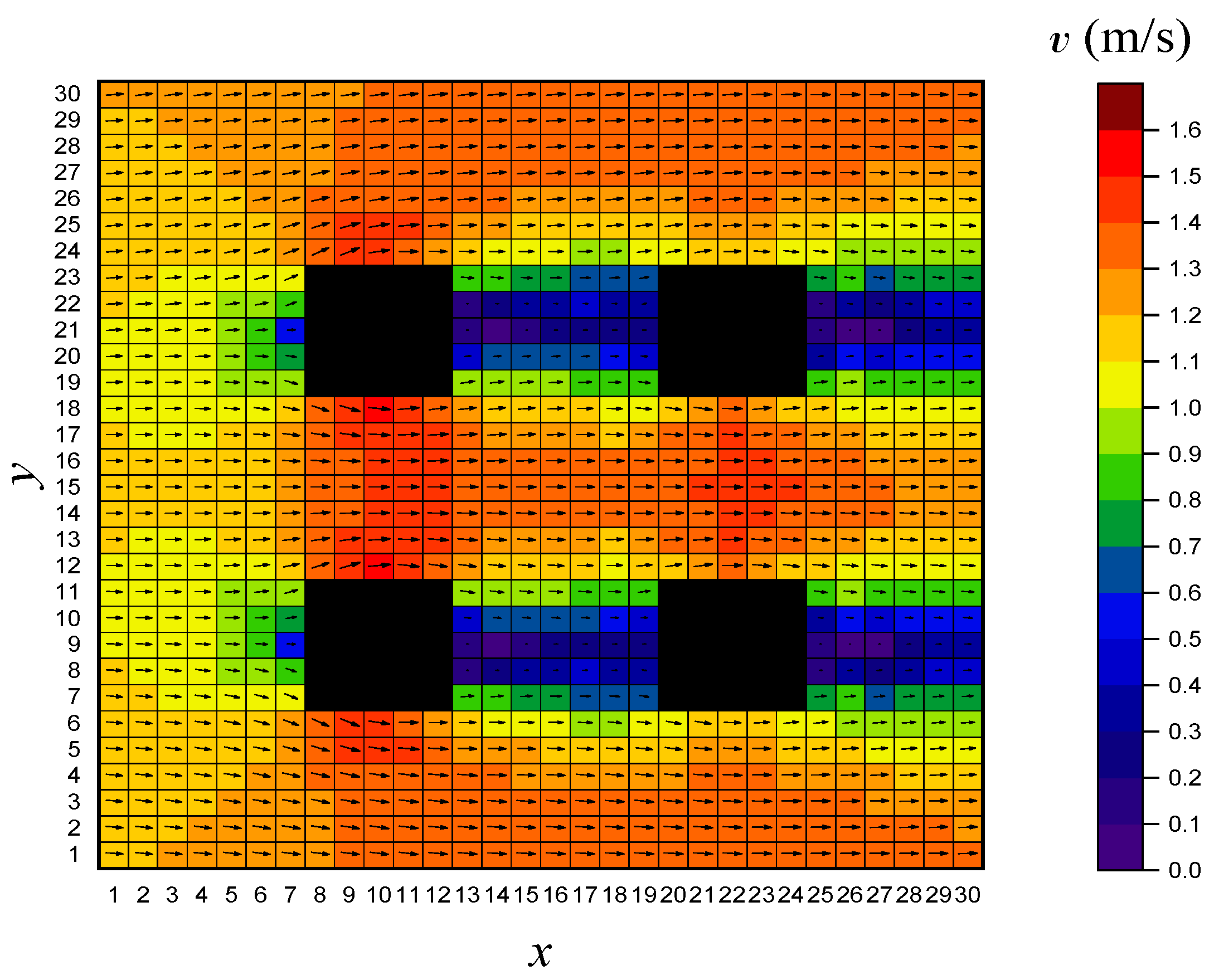

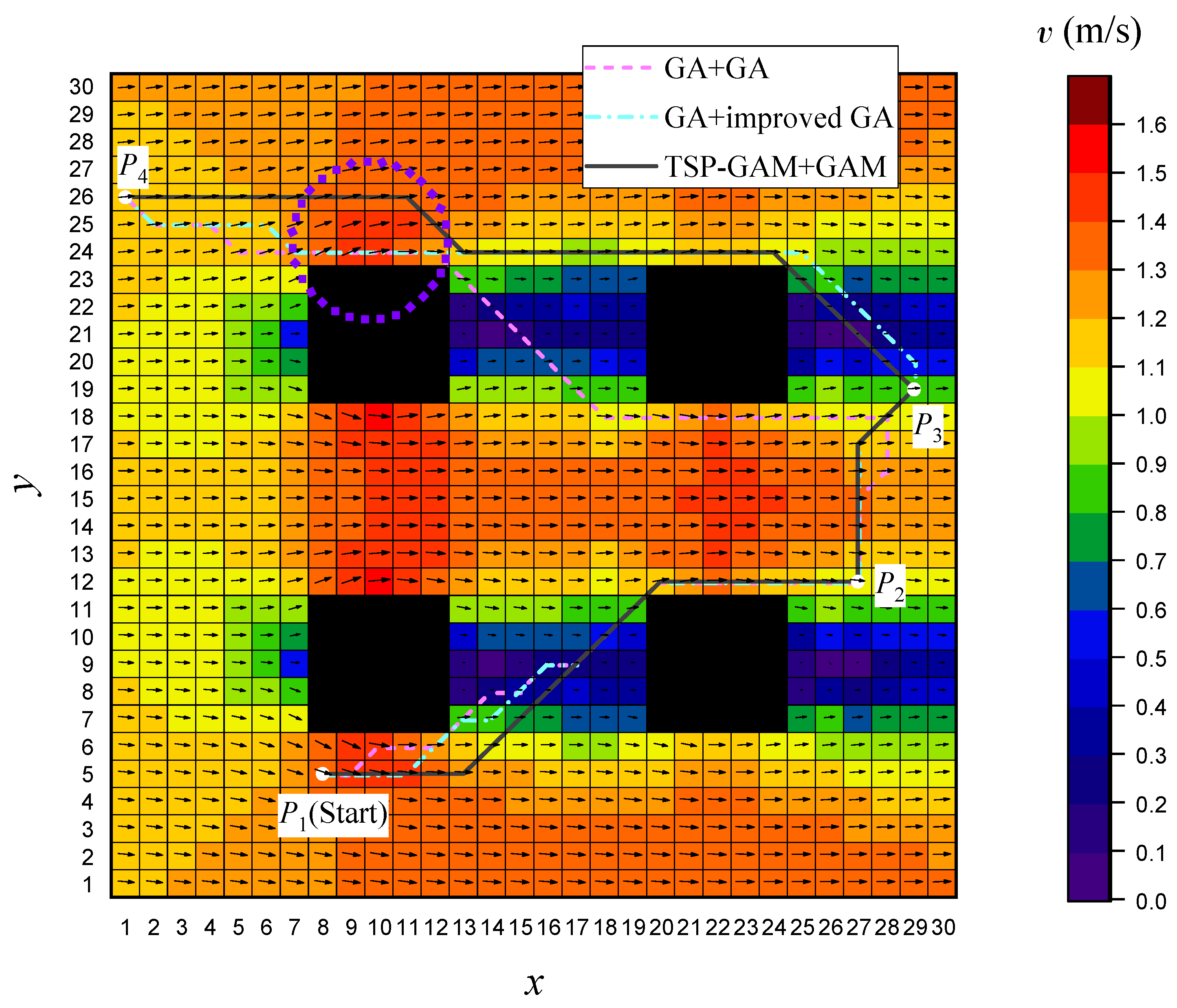

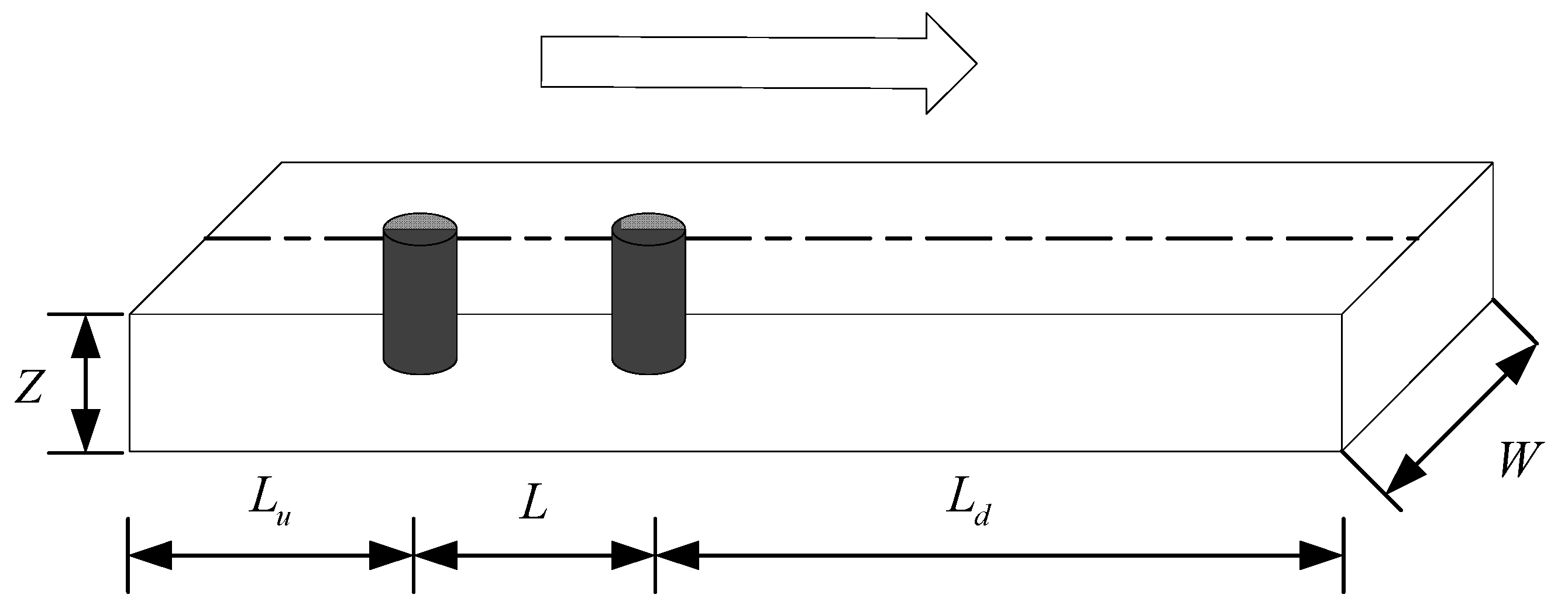

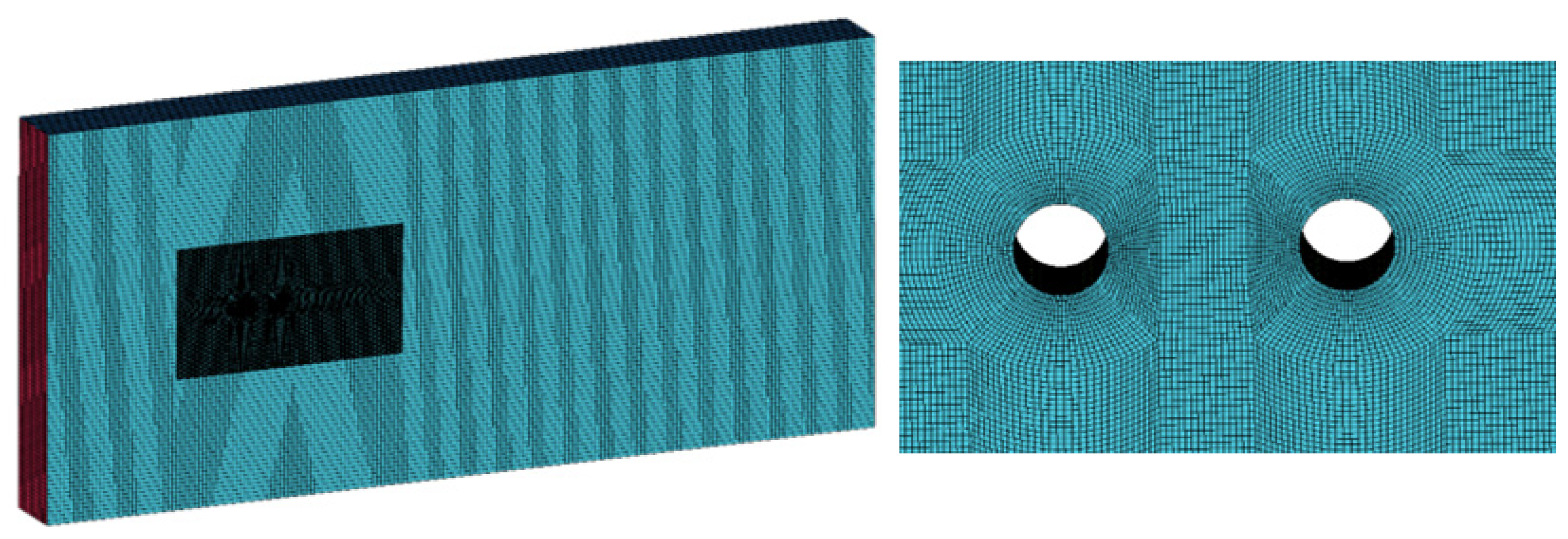

In the scenario of

Figure 1, the underwater vehicle’s starting point is set at coordinates (1, 1), with target points at (a) (20, 20) and (b) (30, 30).

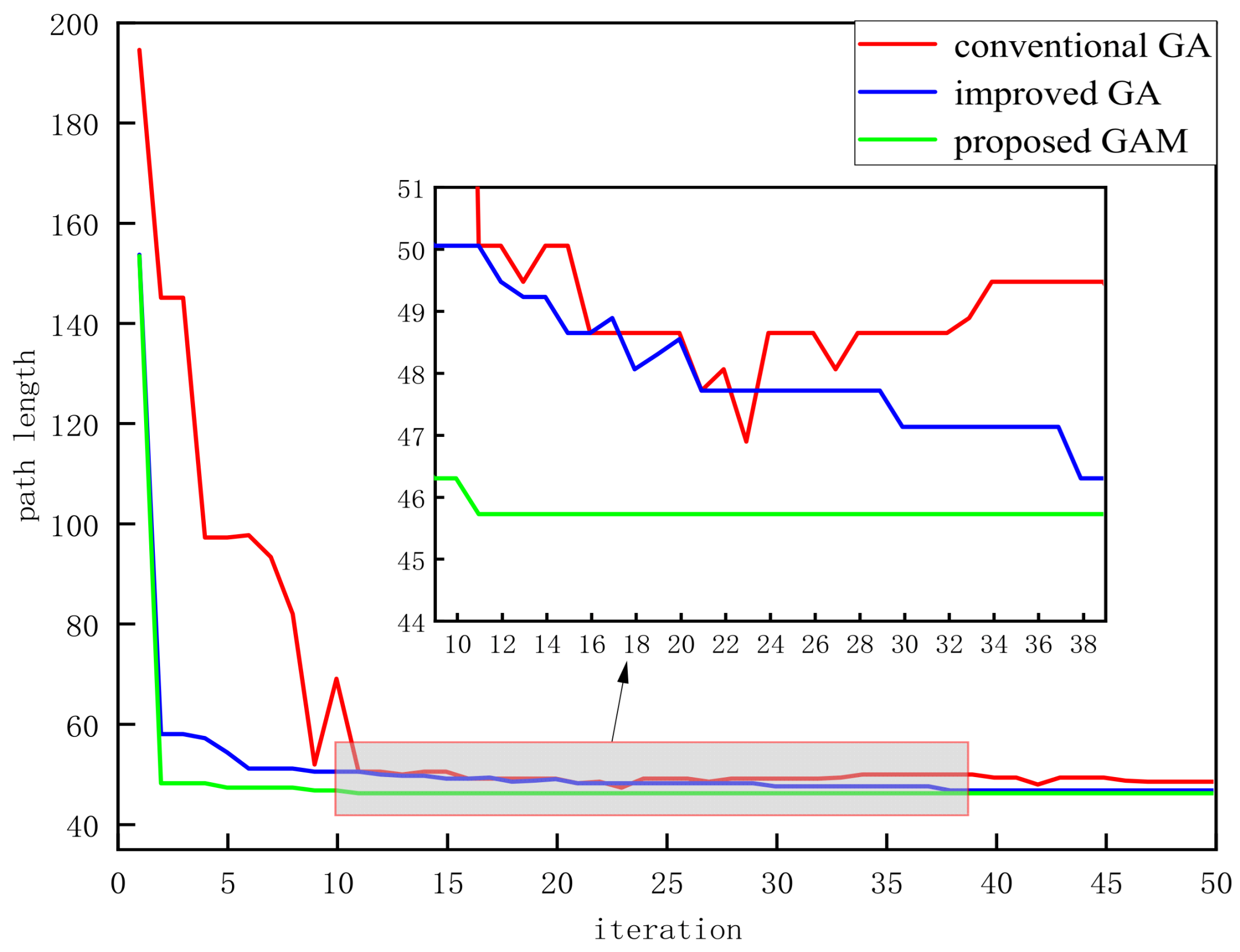

The GAM algorithm parameters are configured as follows: a population size of 50, a crossover probability of 0.8, a mutation probability of 0.2, and a maximum of 50 iterations. The calculation results are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. To eliminate the effects of randomness, each of the three algorithms was executed for 10 independent trials. The experimental results are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 below.

The simulation results indicate that the proposed migration operator enables the GAM algorithm to find the optimal solution faster while also demonstrating superior performance in reducing the inflection points. It is noted that the inflection point is determined by comparing the two movement directions of the adjacent three nodes.

As shown in

Table 1, the proposed GAM algorithm demonstrates superior performance across all evaluated metrics. Specifically, it achieves reductions of 58.57% and 12.78% in the average number of iterations, and 56.76% and 54.6% in the average number of turns, compared to the traditional genetic algorithm and the improved algorithm, respectively.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrates that as map complexity grows, the required iterations and path turns increase, causing algorithm performance to diverge sharply. The traditional GA suffers from severe convergence issues, while the improved GA, though better, yields inadequate paths and slow convergence. The proposed GAM algorithm, however, demonstrates consistent robustness throughout.

As shown in

Table 2, while the traditional genetic algorithm failed to find an optimal path, the proposed GAM algorithm achieved significant efficiency gains. It reduced the average iteration count by 55.33% compared to the traditional GA, and by 35.31% compared to the improved GA. Furthermore, GAM decreased the average number of turns by 32.4% relative to each of them. The simulation results confirm that the advantages of GAM become even more pronounced in complex maps with numerous obstacles.