1. Introduction

As an intelligent waterborne system, the Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) has demonstrated significant application potential in areas such as marine monitoring and investigation, patrol, fishery resource monitoring, and safety inspection of water conservancy facilities. Equipped with a complete control system, sensor system and communication system, USVs can autonomously perform tasks without human control. However, conditions like environmental variability and model uncertainty may affect the performance of the USV control system [

1]. Consequently, achieving accurate trajectory tracking control (ATTC) for USVs has emerged as a pivotal concern within the realm of ocean engineering and control [

2]. An underdriven ship is one in which the number of input dimensions to the control system is less than the number of degrees of freedom [

3]. Its typical feature is the absence of direct driving force in the lateral or longitudinal degrees of freedom. Owing to the strong nonlinearity and actuation constraints of such marine systems, trajectory tracking and stabilization for underactuated ships are particularly challenging.

In studies on trajectory tracking controllers underactuated ships, the main approaches can be classified into two categories: model–based methods and data–driven methods. Common model-based control methods include sliding-mode control (SMC), model predictive control (MPC), linear–quadratic regulation (LQR), adaptive control, and backstepping control. When the controlled object is modeled precisely and its parameters are known accurately, these control methods can fully utilize the information and achieve optimal control performance of the system. Accordingly, model-based control has shown substantial practical value in a variety of control tasks. Several studies on USV trajectory tracking have been built on these methods, including the following: Wei et al. [

4] proposed an anti-saturation backstepping control strategy. Zhu et al. [

5] designed a distributed nonlinear model predictive (NMPC) control method for multi–target tracking surrounding control problem of the multi-USV system. Xu et al. [

6] designed an adaptive line-of-sight (ALOS) guidance to transform the fuzzy adaptive fault-tolerant path following control (PFC) problem into the heading tracking control problem. Chen et al. [

7] proposed a prescribed performance compensation control scheme to reduce the impact of uncertainty on the USV-UAV control system. However, these algorithms hinge on accurate kinematic and dynamic models. Environmental disturbances such as wind and waves often cause mismatches between the plant’s actual dynamics and its model, thereby degrading controller performance. Moreover, when the plant’s dynamic model is intrinsically complex, the design of such controllers and the real-time computation of the control system become more challenging.

Another widely used approach is data-driven control. Rather than directly relying on an explicit mathematical model of the vessel, this approach designs the controller by exploiting the vessel’s input–output mapping and the data collected during operation. Proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control is a representative data–driven method and has been widely applied to the control of USVs [

8,

9,

10]. However, when confronted with systems exhibiting nonlinear, time–varying, or high–order dynamics, PID controllers often fall short of the desired performance and show marked limitations in disturbance rejection.

Within the field of machine learning, reinforcement learning (RL) is an algorithmic paradigm that focuses on how an agent learns through interactions with its environment to maximize cumulative reward [

11]. RL–based controllers adapt parameters in response to environmental feedback and reward signals. Through continuous experimentation and learning, the controller can effectively adapt to dynamic, complex, and uncertain environments [

12]. In recent years, with advances in reinforcement learning, the field of USV control has made significant progress [

13,

14,

15,

16], and numerous exemplary studies have made outstanding contributions to RL-based USV trajectory tracking control. To overcome complex environmental disturbances, Zhou et al. [

17] proposed a deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based policy for USV trajectory tracking control. Wu et al. [

18] proposed a proximal policy optimization (PPO) control scheme for highly coupled systems with nonlinear relationships. Wen et al. [

19] presented a novel approach for achieving high-precision trajectory tracking control through utilization of receding horizon reinforcement learning (RHRL). Wang et al. [

20] introduced an integral compensator to the conventional deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm and thus improved the tracking accuracy and robustness of vessel’s controller. Dai et al. [

21] presented adaptive neural tracking control of underactuated surface vessels with modeling uncertainties and time–varying external disturbances. By leveraging system data, these machine learning–based control methods dispense with reliance on an accurate system model effectively improve the system’s robustness.

To achieve superior control performance, model–based and data–driven methods can be combined to exploit their respective strengths, thereby accommodating diverse models and practical application scenarios. In the field of USV trajectory tracking control research, researchers combine reinforcement learning methods with certain model–based control approaches. By setting rewards to guide the adjustment of controller parameters, they enhance the system’s robustness. Huang et al. [

22] proposed a probabilistic neural networks model predictive control (PNMPC) to avoid the computational complexity associated with sample capacity. Cui et al. [

23] proposed a local update spectrum probabilistic model predictive control (LUSPMPC) approach to enhance the computational efficiency of USV under unforeseen and unobservable external disturbances. Qin et al. [

24] applied DDPG to achieve the optimal control performance for the controlled plant.

Although existing studies have extensively explored USV control from the perspectives of various model-based control methods, deep reinforcement learning, and their hybrid architectures, several critical gaps remain to be addressed. Most existing hybrid approaches focus on coupling RL with conventional controllers at a single level, and their typical forms can be summarized into several categories as shown in

Table 1.

As can be seen, these architectures restrict RL to the role of either a parameter scheduler [

25] or high-level decision-maker [

26], making it difficult to explicitly handle multi-thruster inverse dynamics and complex execution-layer nonlinearities [

27]; or they concentrate complexity in high-dimensional models and model–based receding–horizon optimization, which imposes stringent requirements on real-time performance and engineering deployment and makes the controller highly sensitive to model structure and system dimension.

For USV trajectory-tracking tasks with kinematic constraints and complex hydrodynamic characteristics, existing work still falls short of fully decoupling the problem in a hierarchical manner. Most methods either directly employ robust or adaptive control and single–layer model–based controllers at the dynamics level, or use RL for high–level path planning, parameter scheduling, or model learning. Such approaches typically depend on relatively accurate dynamic or hydrodynamic modeling. When the plant exhibits unmodeled dynamics, contains parameters that are difficult to obtain, or suffers from uncertainty in the specific parameter values and identification procedures, it becomes challenging to guarantee control performance and closed–loop stability, and the resulting controllers exhibit limited transferability.

Moreover, existing RL-based control studies mostly rely on static, manually specified reward functions based on prior knowledge. These rewards remain fixed throughout training and cannot promptly reflect the dynamic performance requirements of the plant in complex, time-varying environments, which leads to pronounced limitations in terms of convergence smoothness and robustness to disturbances.

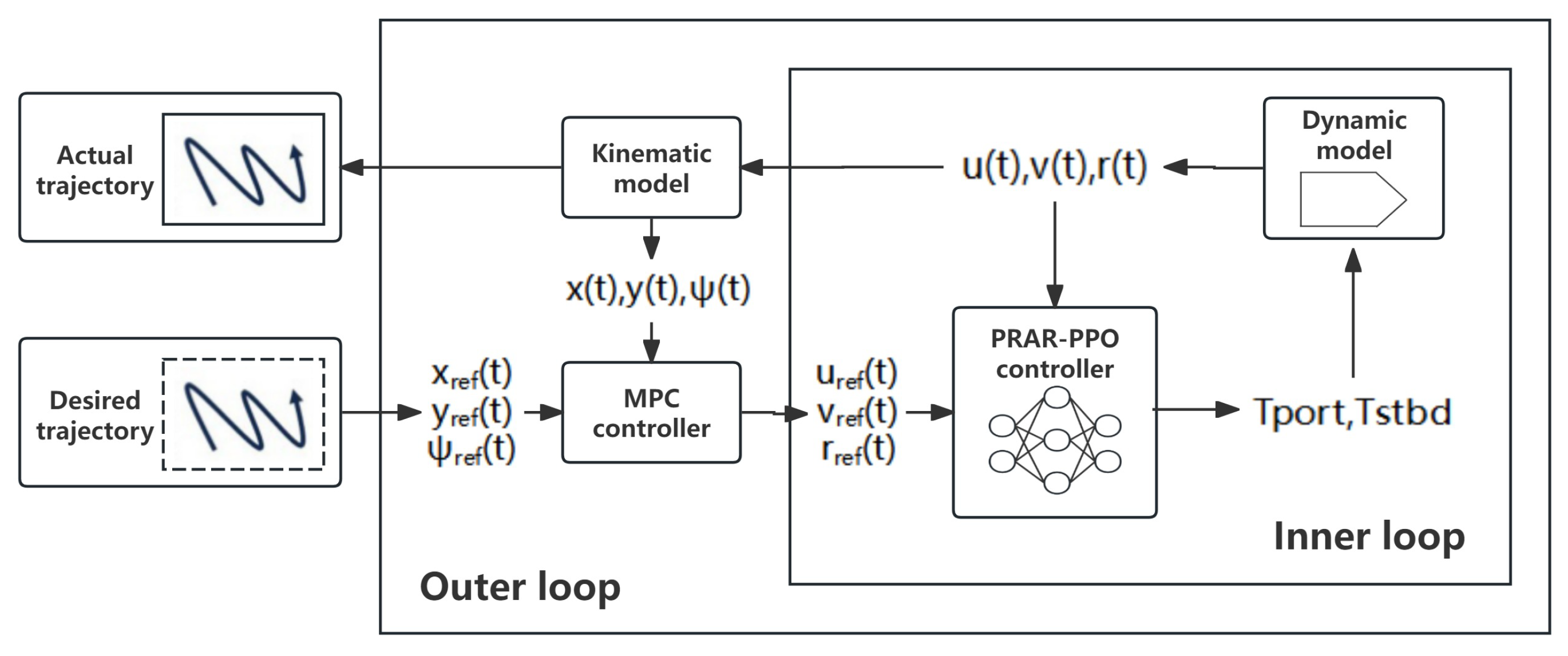

Motivated by the above gaps, we design a Proactive–Reactive Adaptive Reward (PRAR)-driven dual–loop USV trajectory–tracking controller, referred to as the PRAR–driven Dual–Loop Controller (PRAR–DLC). The outer loop of this controller adopts Model Predictive Control (MPC), while the inner loop employs Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The overall objective is to ensure constraint feasibility at the trajectory–planning level and to achieve high–precision, adaptive, and cross–model generalizable control at the dynamic execution level within a unified control framework. Specifically, the aims of this study are as follows:

- (1)

Construct a dual–loop structure with kinematic–dynamic hierarchy.

In the inertial reference frame, the outer loop designs a planning controller based on MPC, performing receding–horizon optimization on a simplified kinematic model. By explicitly incorporating speed, acceleration, and safety constraints, it guarantees the dynamic feasibility of the reference velocity commands. In the body–fixed reference frame, an execution controller is designed for the inner loop. This controller is structurally decoupled from the outer loop so that constrained planning and dynamic tracking are handled by different loops, forming a clear hierarchical control architecture.

- (2)

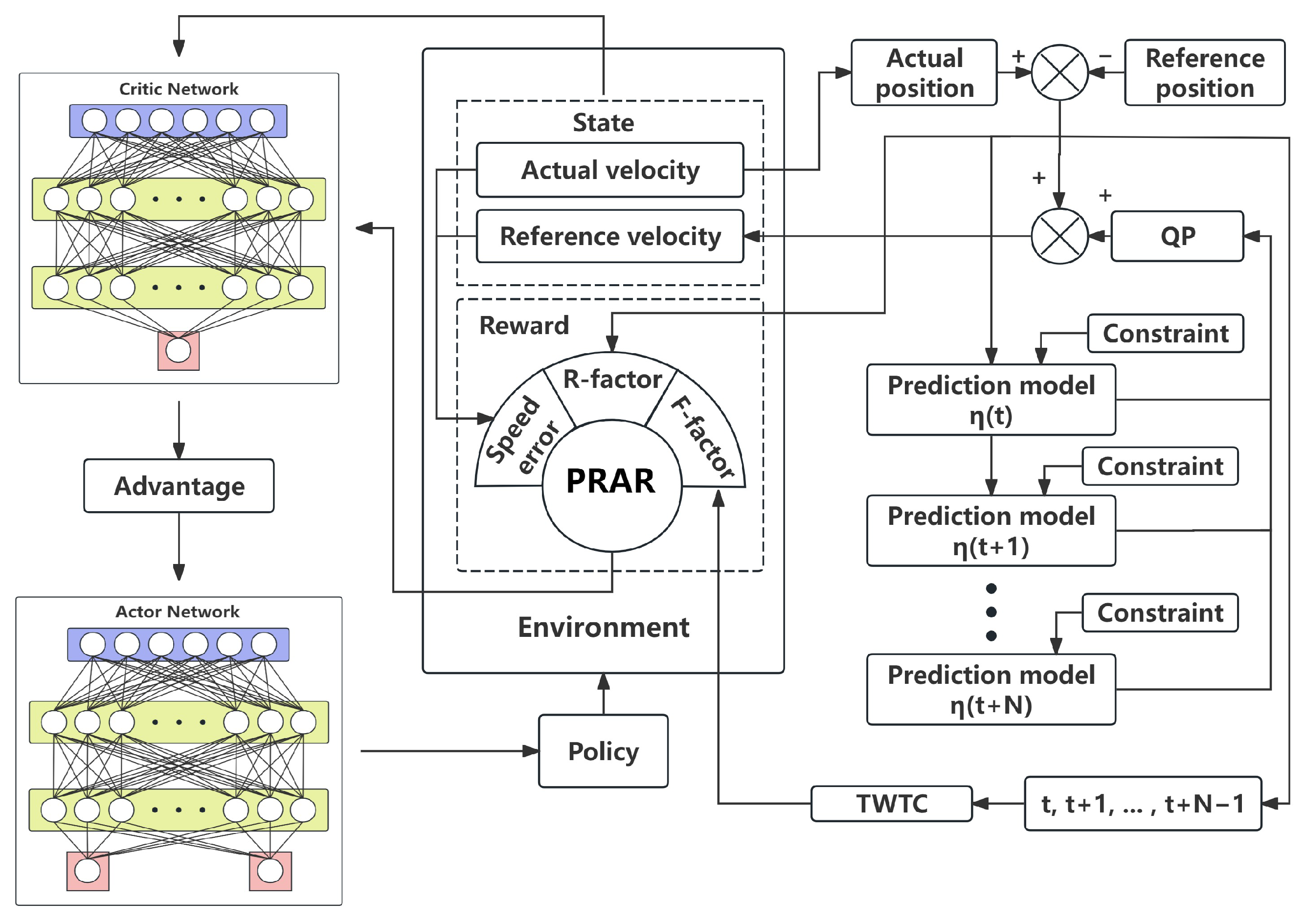

Employ reinforcement learning exclusively at the execution layer to achieve weak dependence on complex dynamics and cross–model generalization.

In the inner loop, we introduce a PPO–based policy network that directly learns a nonlinear inverse–dynamics and compensation mapping from the outer–loop velocity references and USV state observations to thruster forces. In this way, complex hydrodynamic effects and multi–thruster couplings are absorbed into the learned RL policy instead of being explicitly modeled via a detailed dynamic description. The outer loop only requires a simplified kinematic model to generate feasible references, and the control architecture is structurally decoupled from the specific USV dynamics. Consequently, when changing the vessel type or propulsion configuration, one only needs to retrain or fine–tune the inner–loop policy to complete controller transfer.

- (3)

Develop a Proactive–Reactive Adaptive Reward (PRAR) to enhance the training efficiency and robustness of the inner–loop PPO.

Leveraging the hierarchical information of the dual–loop structure, we design an adaptive reward mechanism that simultaneously accounts for anticipated future trajectory trends and the current pose–tracking error, allowing the reward to adjust dynamically with the system state and trajectory evolution rather than remain fixed. By using PRAR to shape the PPO update process in a targeted manner, the learned policy attains heightened sensitivity to both long–term trajectory quality and instantaneous tracking error, thereby outperforming conventional static reward designs in terms of sample efficiency, convergence smoothness, and robustness to disturbances and model uncertainties.

The PRAR–DLC, through the coordinated division of labor between the outer–loop MPC and inner–loop PPO, is designed to provide a hierarchical intelligent control scheme for USV trajectory tracking in complex hydrodynamic environments and under diverse propulsion configurations, simultaneously ensuring constraint safety, weak dependence on explicit models, and cross–platform transferability.

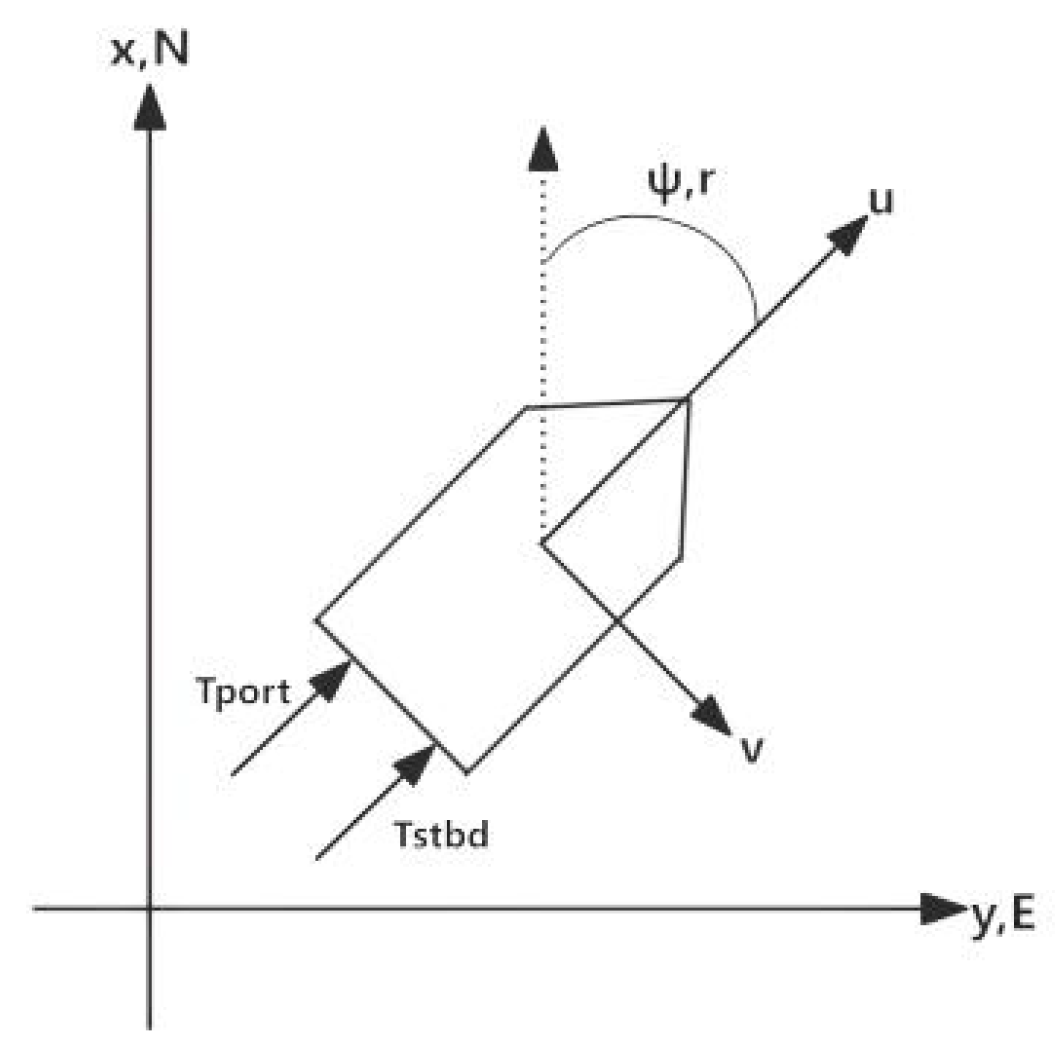

2. USV Dynamic Model

For USV trajectory tracking, three–degree–of–freedom (3–DOF) kinematic and dynamic models are typically formulated and analyzed. For notation, we adopt the convention introduced by Fossen [

28]. The controlled vessel is a waterjet propulsion vessel with fixed thruster vector angles [

29]. An illustration of the vessel in the inertial and body-fixed reference frames is provided in

Figure 1.

The USV model comprises two parts [

29]. The first relates the 3–DOF control inputs—surge force, sway force, and yaw moment—to the dynamics governing the vessel’s velocities, and can be written as:

where

is a vector of forces and moments generated by the port and starboard thrusters:

is the inertia matrix, comprising the vessel mass, moments of inertia, and added–mass terms, and it characterizes the inertial properties during acceleration.

is denoted by:

The Coriolis matrix

captures the coupling between inertia and velocity; it is typically skew-symmetric and accounts for Coriolis and centripetal effects during motion.

is expressed as:

The damping matrix

describes the influence of fluid damping and frictional losses on the vessel’s motion and usually contains both linear and nonlinear components.

is denoted by:

The velocity vector

denotes, in the body-fixed reference frame, the surge and sway linear velocities and the yaw rate with physical units

and

, respectively.

The second part of the model describes the kinematic mapping between the body-fixed and inertial reference frames, transforming body-fixed velocities into the time derivatives of the inertial-frame pose, and is given by:

where

denotes the position and heading in the inertial reference frame, and

is the coordinate transformation matrix that maps velocity vectors between the body-fixed and inertial reference frames:

The kinematic relations are formulated in an East–North–Up (ENU) right–handed inertial reference frame. Therefore,

corresponds to a counterclockwise rotation in the horizontal plane.

In the vessel’s dynamic model, the values of certain elements in

,

and

are determined by the vessel’s structural configuration. Moreover, the entries of

and

are velocity-dependent, and considerable parameter uncertainty is exhibited [

30].

In this study, the specific values of the aforementioned parameters and the identification methods can be found in [

1]. This USV dynamic model provides the foundational basis for the entire control system; subsequent controller design and simulation experiments are conducted on this model.

5. Conclusions

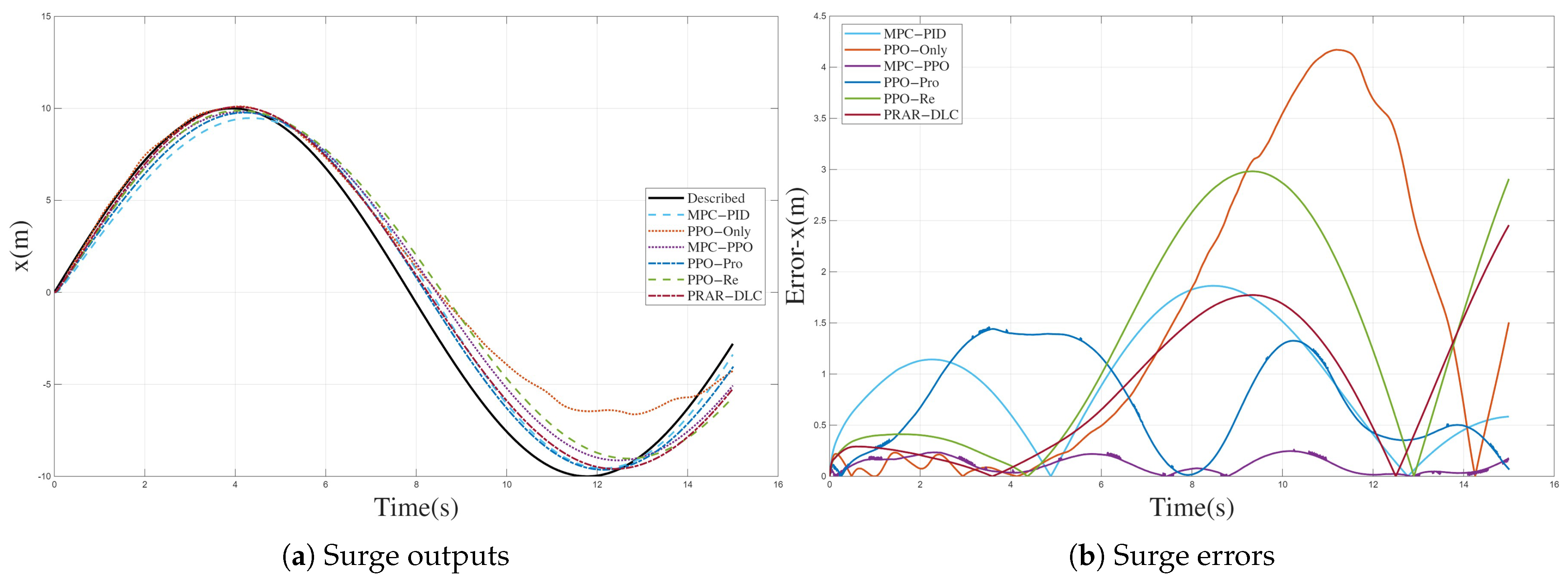

This study proposes a dual–loop USV trajectory–tracking framework that combines MPC with PPO. The USV dynamics are explicitly decoupled into a kinematic layer and a dynamic layer, for which the outer and inner controllers are designed, respectively. In the outer loop, an MPC planner operating in the inertial reference frame uses a kinematic model and explicit velocity and safety constraints to generate dynamically feasible body–fixed velocity references together with a prediction sequence over the horizon. In the inner loop, a PPO–based execution controller operating in the body–fixed reference frame learns the nonlinear inverse mapping from commanded velocities to multi-thruster forces and performs online compensation for unmodeled hydrodynamics and external disturbances. This design enforces a feasible–first–then–refine behavior, in which the policy is guided to remain within the outer–loop feasible set while progressively improving tracking accuracy. Building on this dual-loop structure, we further design a Proactive–Reactive Adaptive Reward (PRAR) mechanism that fully exploits the outer loop’s prediction sequence in combination with real–time pose–tracking errors: PRAR derives a time–weighted trajectory–complexity measure from the predicted velocities and adaptively reweights the surge, sway and yaw components of the reward, allowing the controller to anticipate upcoming aggressive maneuvers while remaining sensitive to instantaneous deviations.

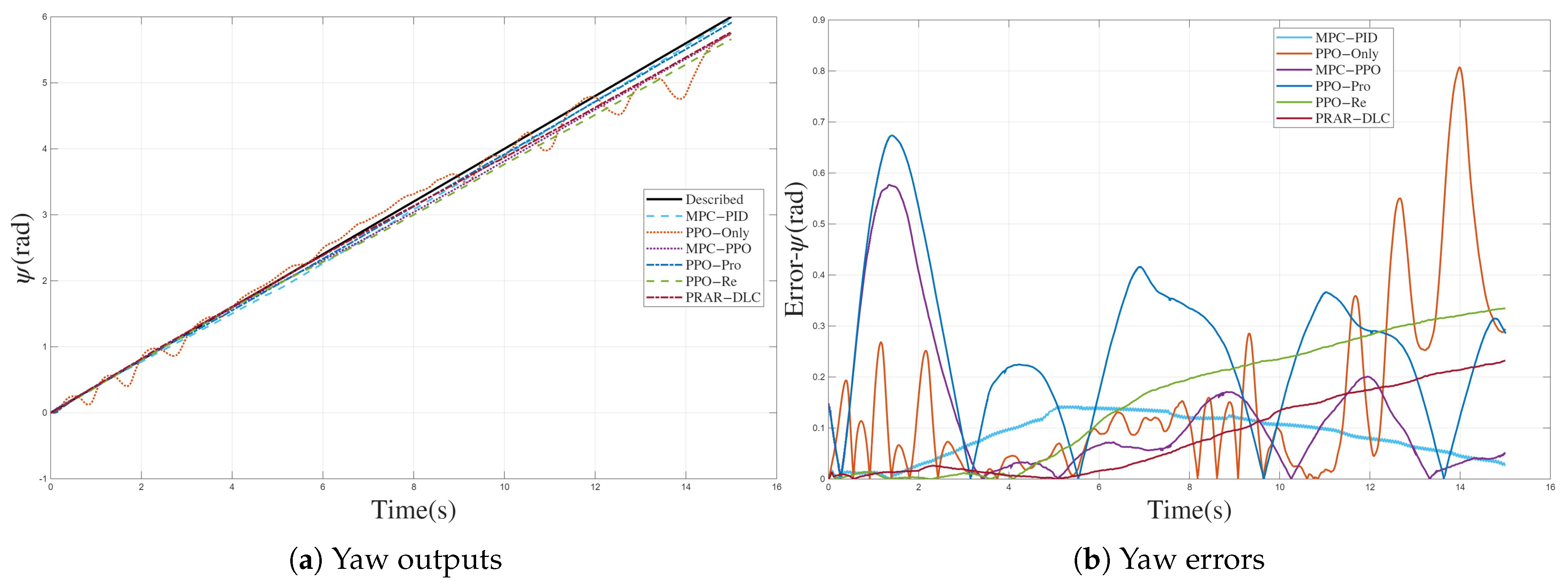

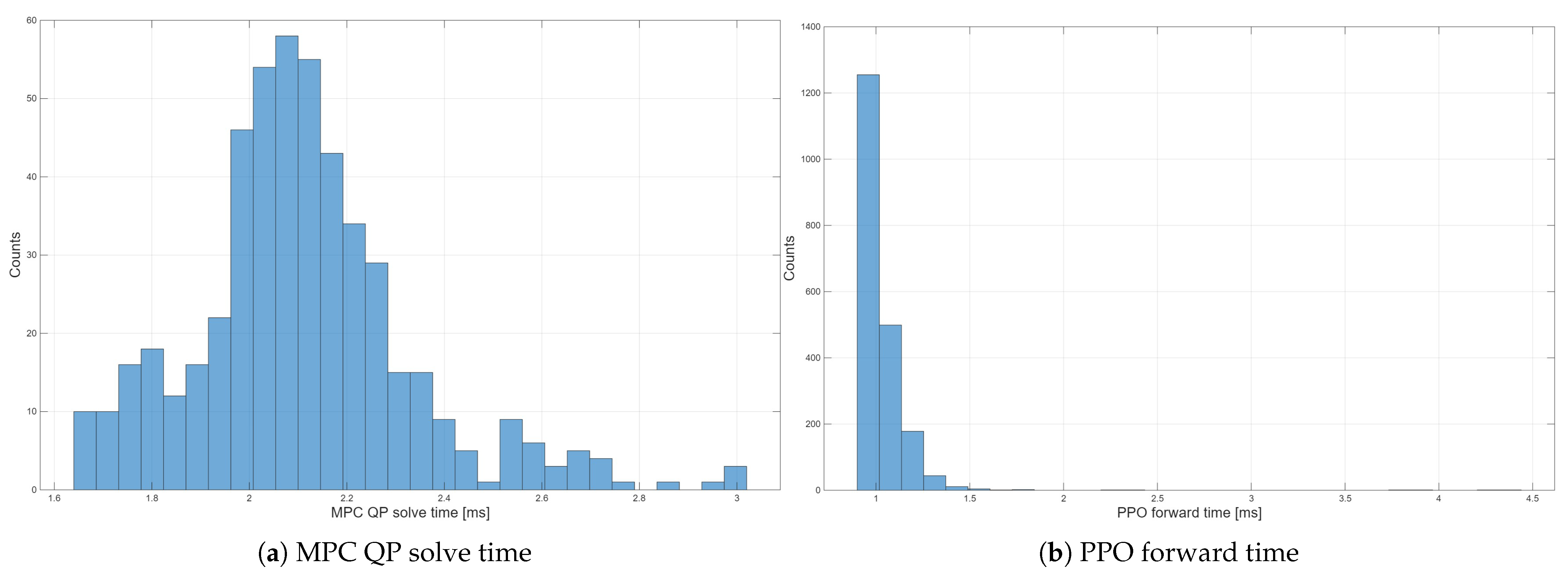

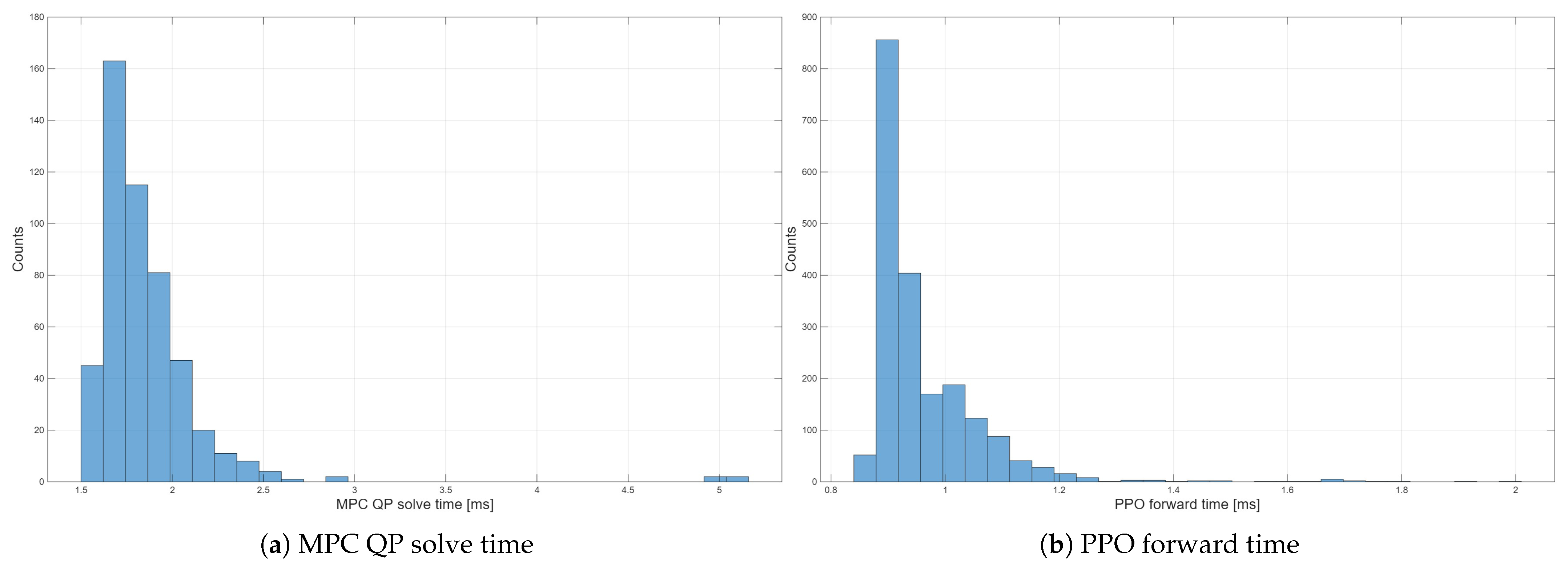

The simulation results on both circular and curvilinear trajectories show that the USV controlled by the proposed framework maintains high–precision tracking under disturbances and model mismatch. Compared with a nominal hydrodynamic MPC–PID baseline, the PRAR–driven dual–loop controller reduces surge MAE and maximum longitudinal error on the curvilinear trajectory from 0.269 m and 0.963 m to 0.138 m and 0.337 m, respectively, and achieves about an 8.5% reduction in surge MAE on the circular trajectory while keeping sway and yaw MAE at a level comparable to the baseline. Across all scenarios, it also significantly suppresses error tails and avoids the large drifts or oscillations observed in PPO–Only, MPC–PPO and other PPO variants, confirming strong robustness. In addition, the proposed PRAR mechanism integrates the outer–loop MPC prediction sequence with real–time pose errors to adaptively reweight the reward, which, compared with fixed–weight PPO, improves generalization capability while keeping the average MPC and PPO computation times in the low–millisecond range, compatible with real–time on–board implementation.

Future work will focus on two directions. First, hardware–in–the–loop and full-scale waterborne experiments will be conducted to validate the controller under unmodeled actuator dynamics, onboard sensor noise, and network–induced latency. Second, to further reduce computation load and facilitate deployment on resource–limited USVs, we will investigate model lightweighting, including reduced–order MPC, neural surrogate models for prediction, and compact policy networks for thrust allocation. Extending the framework to over–actuated USVs and cooperative multi–vessel missions also constitutes a promising direction for the hierarchical architecture introduced in this study.