A Hybrid Statistical and Neural Network Method for Detecting Abnormal Ship Behavior Using Leisure Boat Sea Trial Data in a Marina Port

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Establishment of Criteria for Detecting Abnormal Ship Behavior

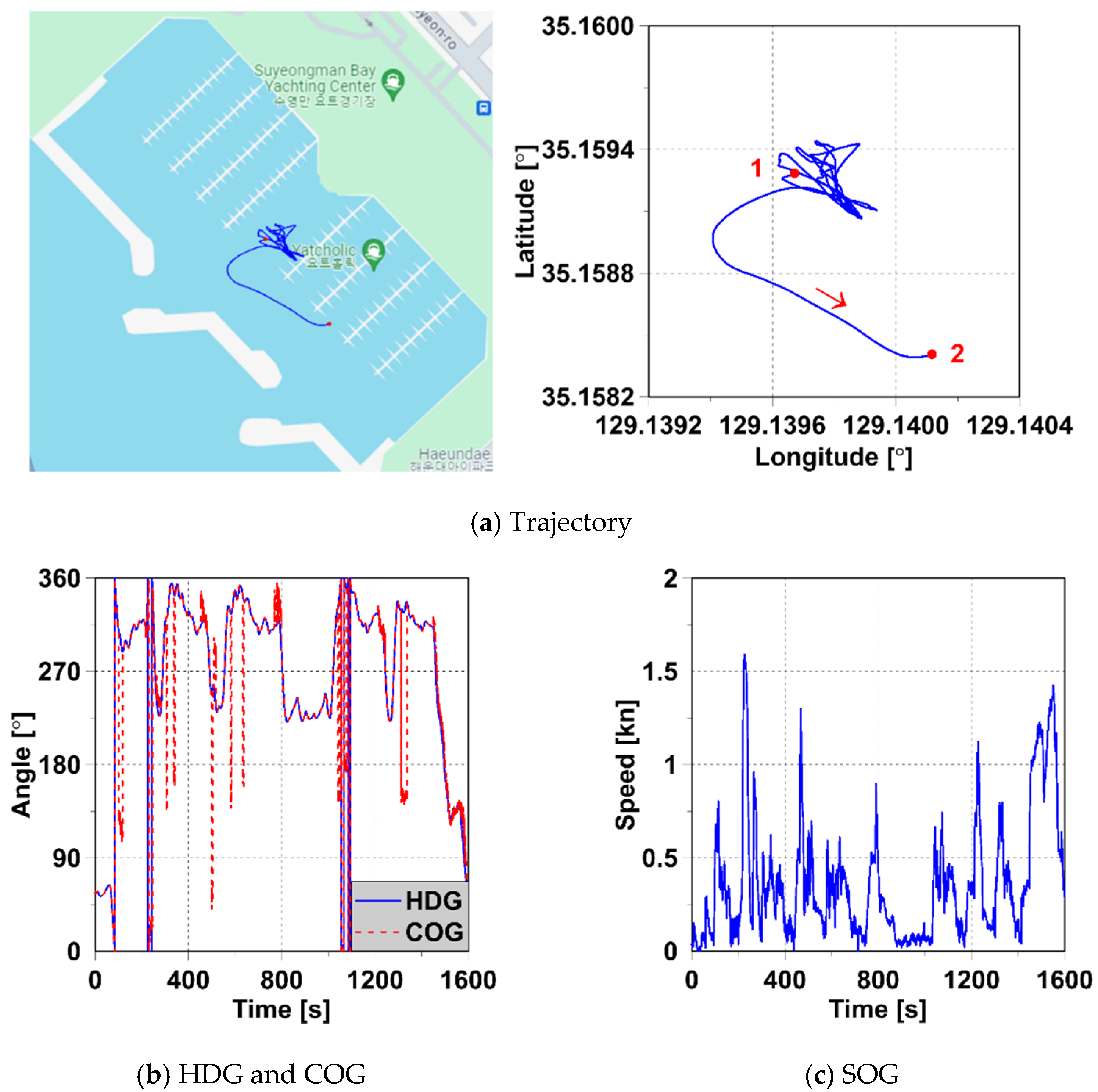

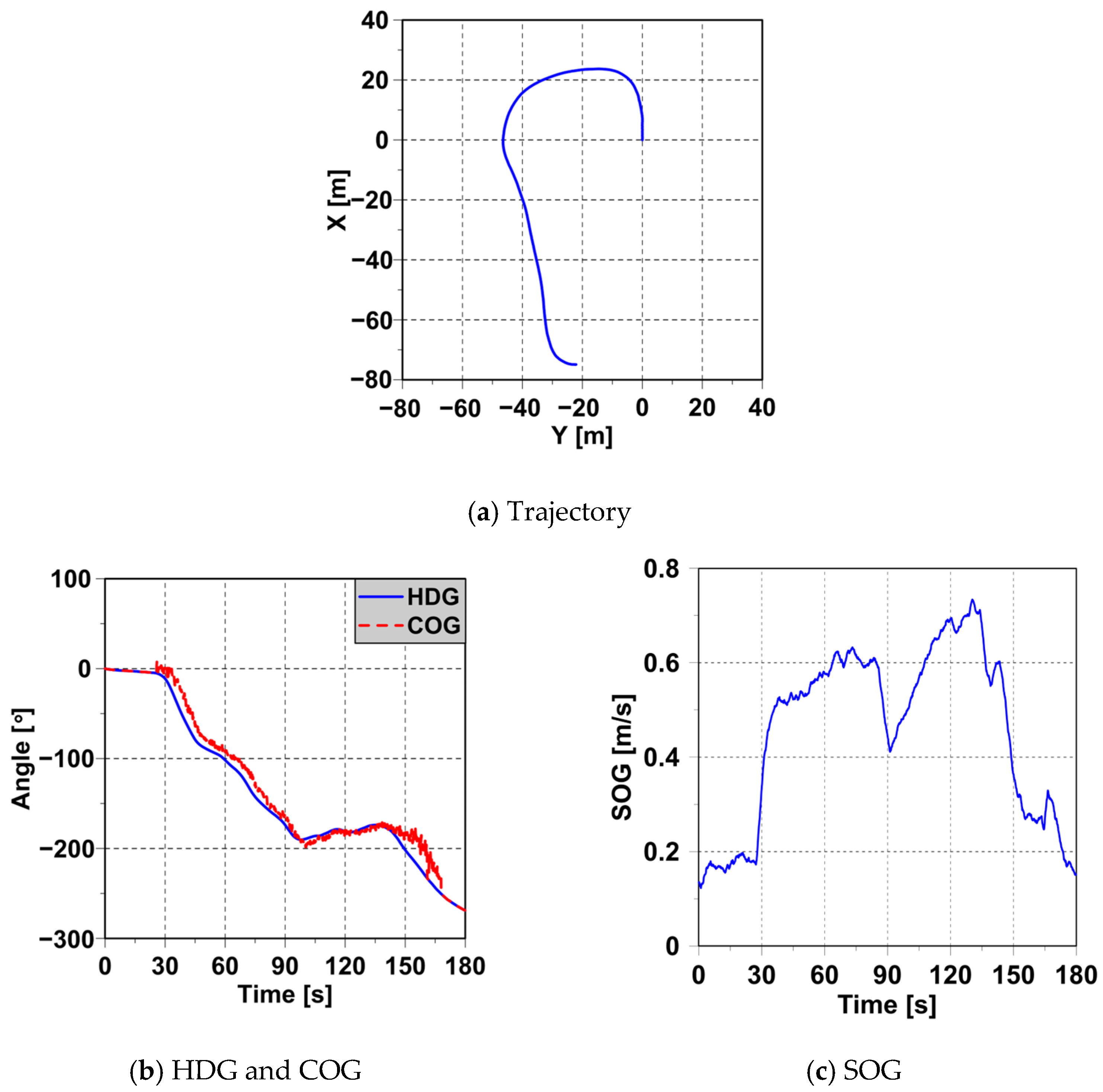

2.1. Target Ship and Sea Trial Data

2.2. Establishment of Criteria

- Sudden speed changes: Boats in port areas usually change their speed slowly. This is because ports are narrow and crowded, and there are safety rules to follow. A sudden increase or decrease in speed may indicate evasive action, mechanical issues, or unintentional throttle control, which could lead to collisions or loss of control.

- Unusual course changes: In a port, boats usually follow a smooth and steady course along marked paths. Large or sudden changes in course could mean that the boat is trying to avoid an object, has made a wrong turn, or the operator is inexperienced. These issues are more common for leisure boats, where drivers may not have formal training.

- Extended stationary periods: In a port area, boats are expected to stop only at designated docks or anchoring zones. If a leisure boat stays still for a long time outside these zones, it may indicate loitering, unauthorized activity, or engine trouble. Because space in ports is limited and tightly managed, unexpected stops can disrupt operations and raise safety or security concerns.

- Deviation from the expected route: Boats in port usually follow fixed or expected routes. Large or repeated deviations from these routes may happen if the operator does not know the local rules, is intentionally entering off-limit areas, or is experiencing navigation problems. This is especially important for leisure boats, which may not have advanced navigation systems and often rely on visual guidance. In this study, the expected route is assumed to be the normal route, which is predicted by the LSTM model.

- Complex maneuvers: Under normal port conditions, the boat moves in smooth lines and avoids sudden or complex turns. Maneuvers like zigzaging, turning, or tight looping are rare and often happen during testing, risky behavior, or when the operator loses control. Spotting these actions is important in areas where both commercial and leisure boats operate together.

- Track continuity issues: In this study, sea trial data were collected from onboard navigation sensors, which usually provide continuous tracking. However, if there are frequent gaps or missing data, it may mean that the equipment failed or someone has turned off the system on purpose. These tracking problems make it hard to monitor behavior accurately and could signal rule violations or suspicious activity.

3. Methodology

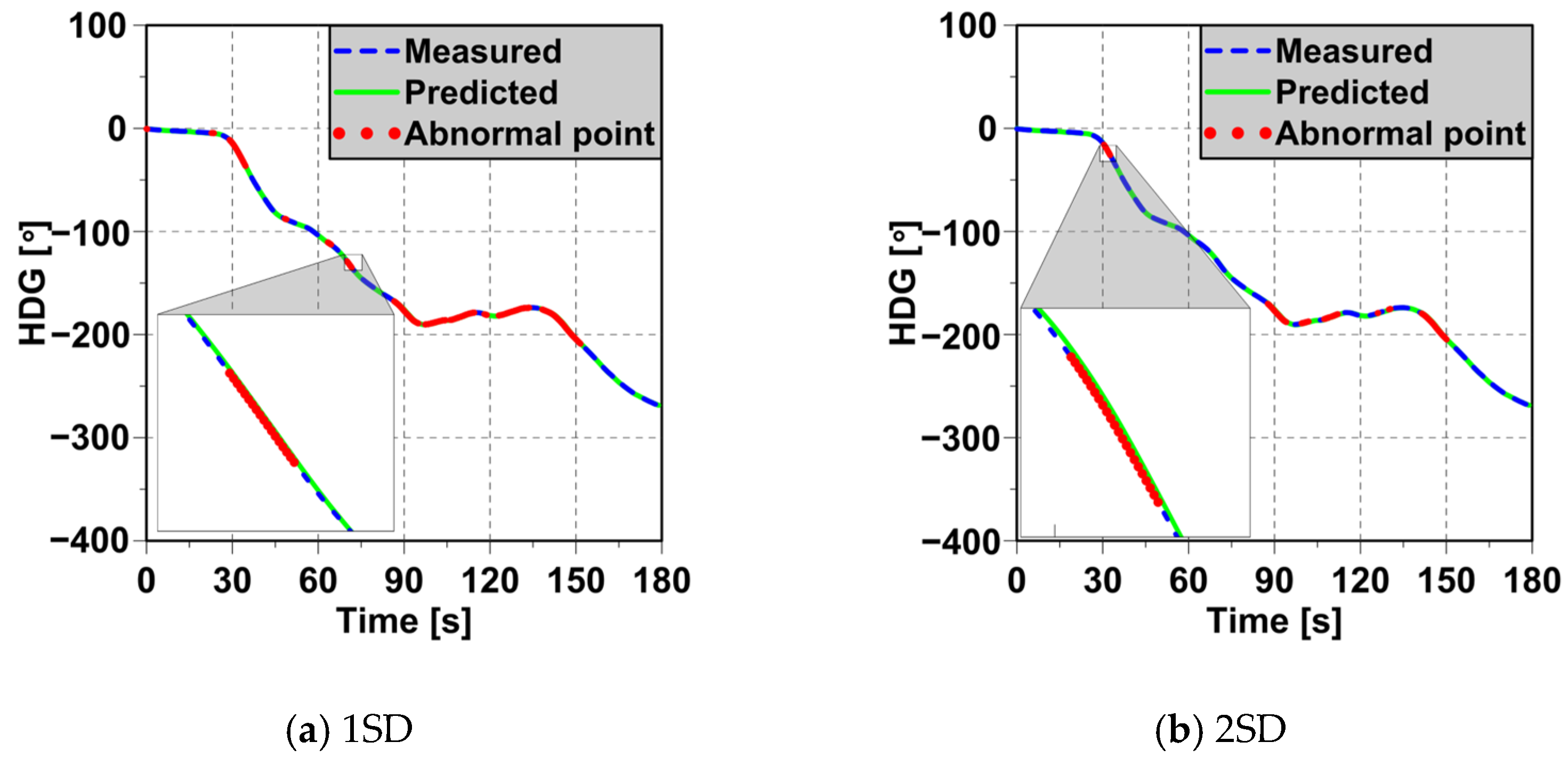

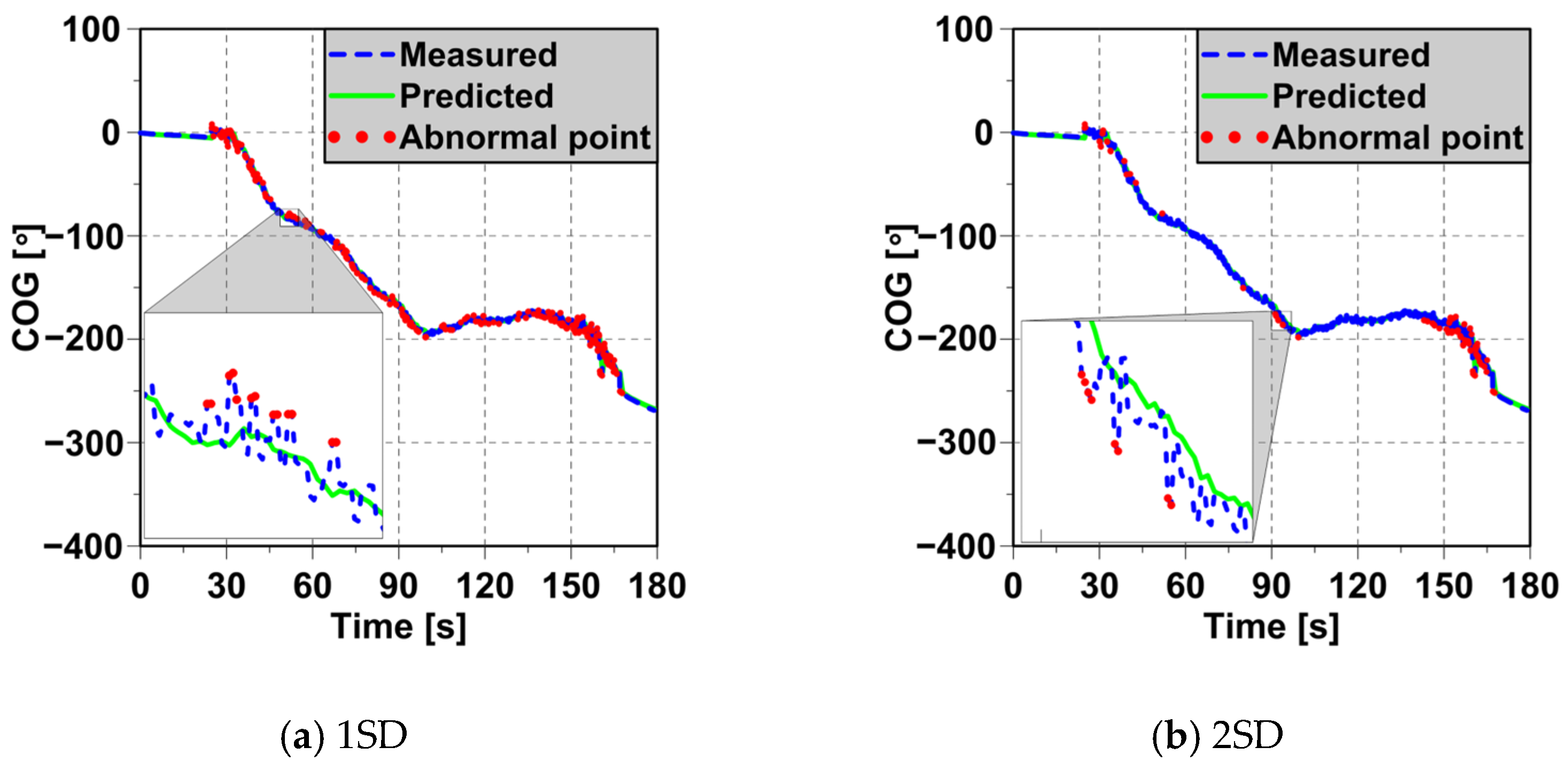

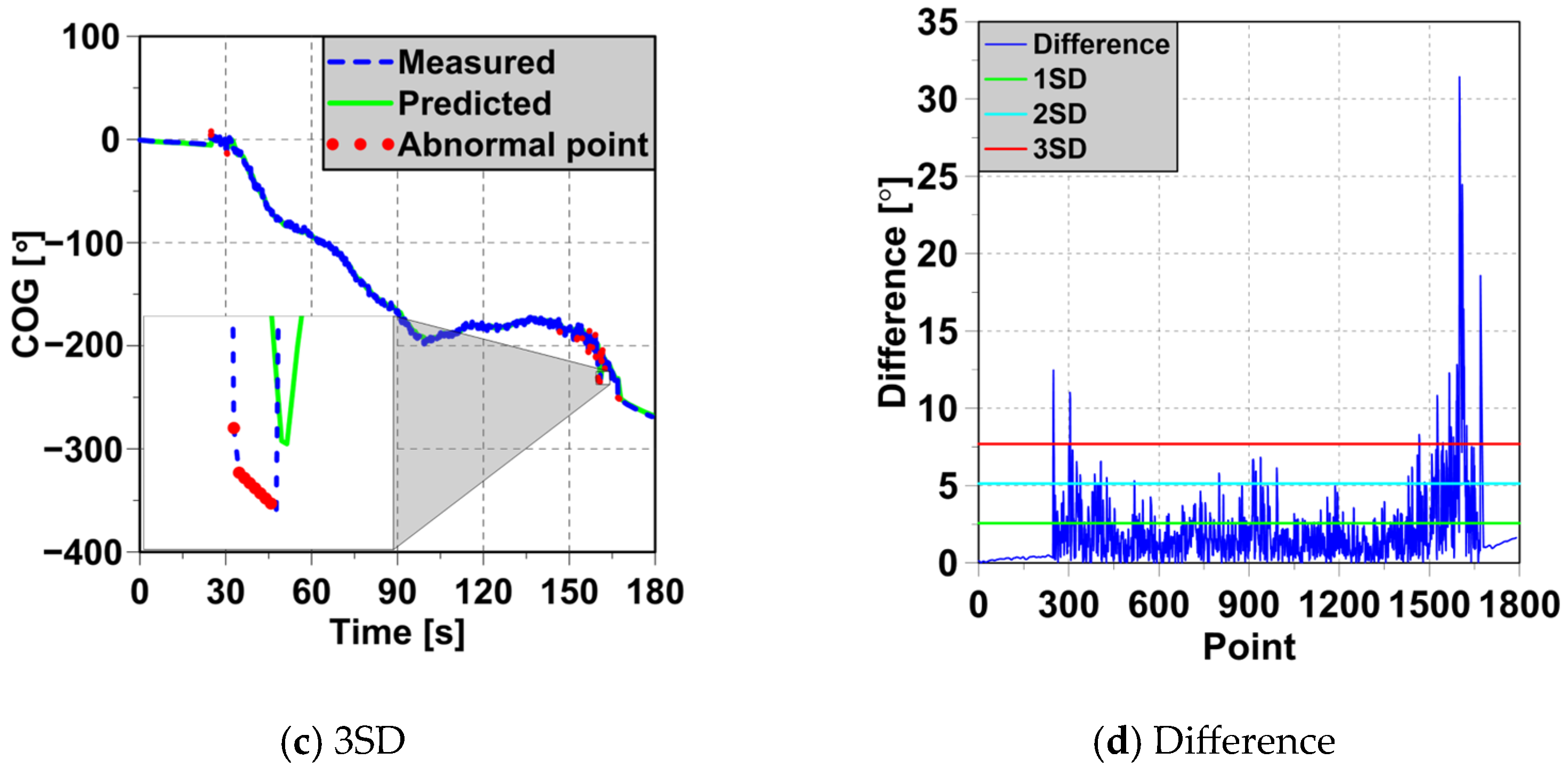

3.1. Rayda’s Criterion and Standard Deviation

| Algorithm 1: Rayda’s criterion for abnormal behavior detection. |

| Input: Time-series data Threshold multiplier Step 1: Compute the mean and the standard deviation for each variable for each time index do for each variable do if then Add to outlier set end if end for end for Output: Outlier set |

3.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Network

| Algorithm 2: Grid search for LSTM model architecture. |

| Input: Time series data Window size Grid search space: Number of layers Units per layer Number of training epochs Loss function (Mean Squared Error) Step 1: Sequence generation Create input-output pairs from overlapping windows: Step 2: Data splitting Partition into training and validation sets: Step 3: Grid search over architectures for each architecture do Build LSTM model with: Input shape , where is the number of variables stacked LSTM layers, each with units Training using for epochs, minimizing: Evaluate validation loss Track best architecture: end for Output: Final training and validation losses for all Epoch-wise training history Best architecture () |

| Algorithm 3: LSTM model for normal behavior prediction. |

| Input: Time-series data Window size Step 1: Data standardization for each variable do Compute mean and standard diviation Normalize: end for Step 2: Sequence generation (Windowing) for to do Input sequence: , where Target output: end for Step 3: LSTM model calculation for each input sequence do for each time step to do Forget gate: Input gate: Candidate cell state: Cell state update: Output gate: Hidden state: end for Predicted output: Step 4: Prediction recovery (Inverse transform) for each predicted value do Recover original scale: end for Output: Predicted normal sequence: |

4. Results and Discussion

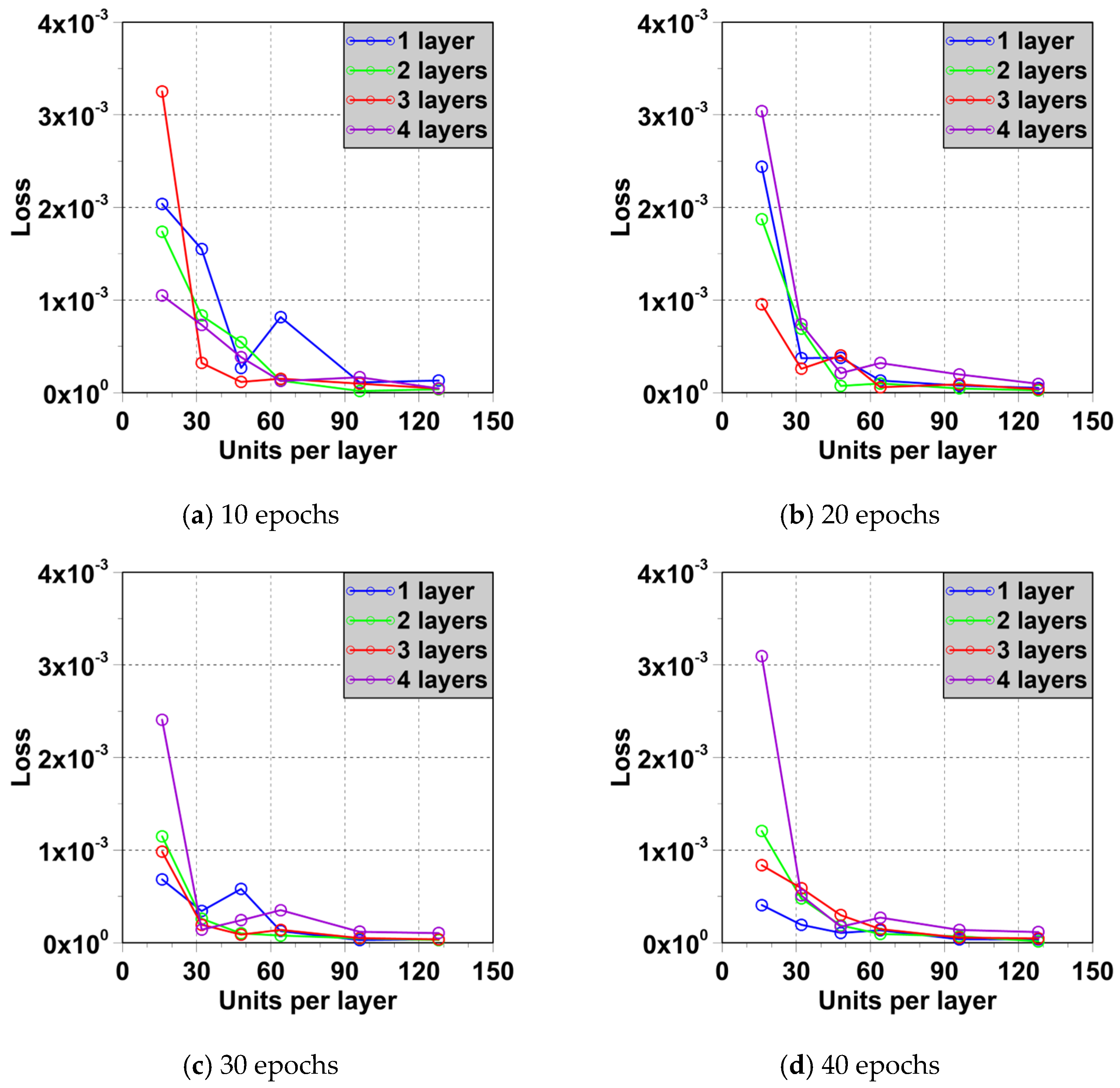

4.1. Training of LSTM Model

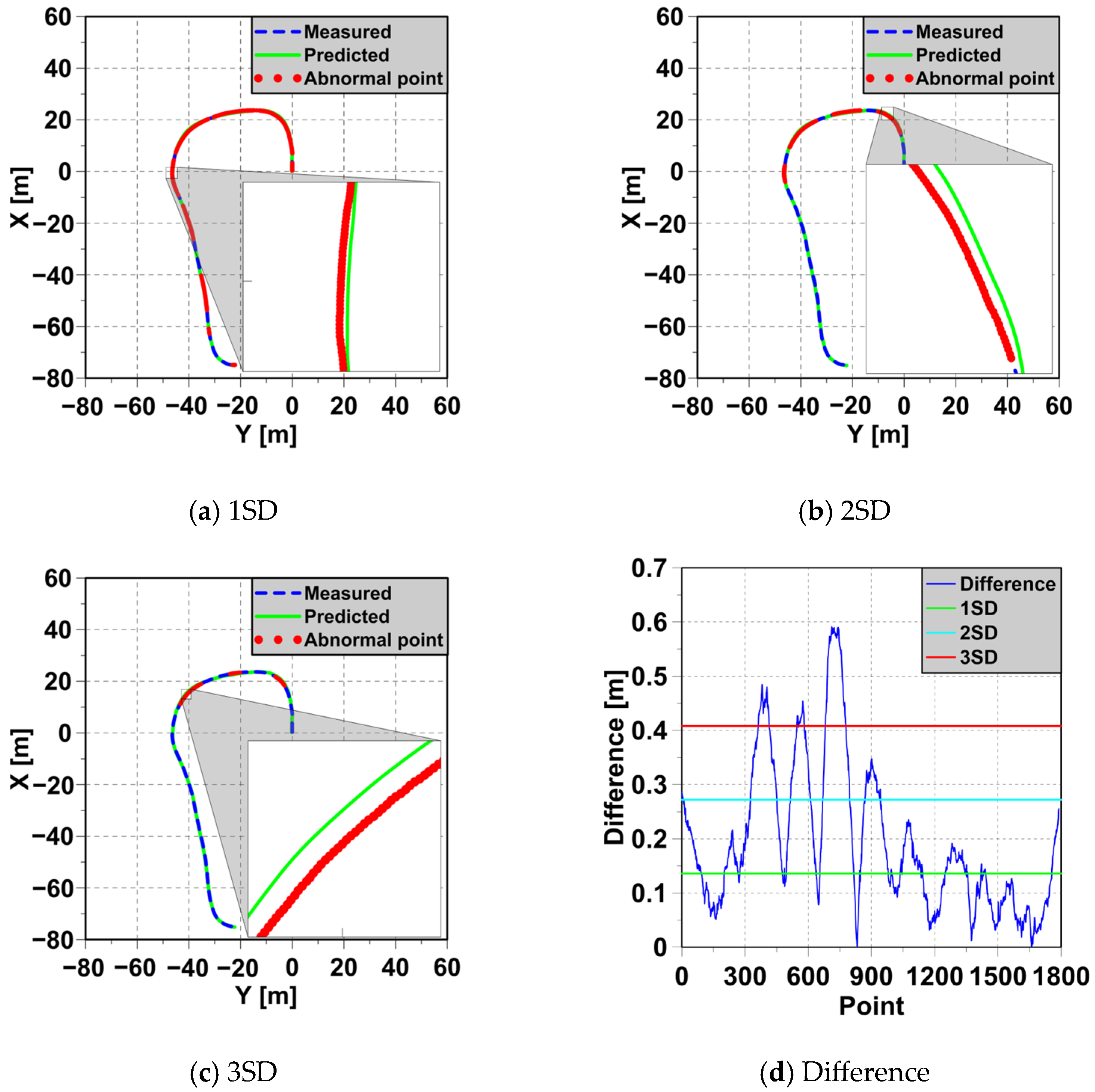

4.2. Prediction of Normal Ship Behavior

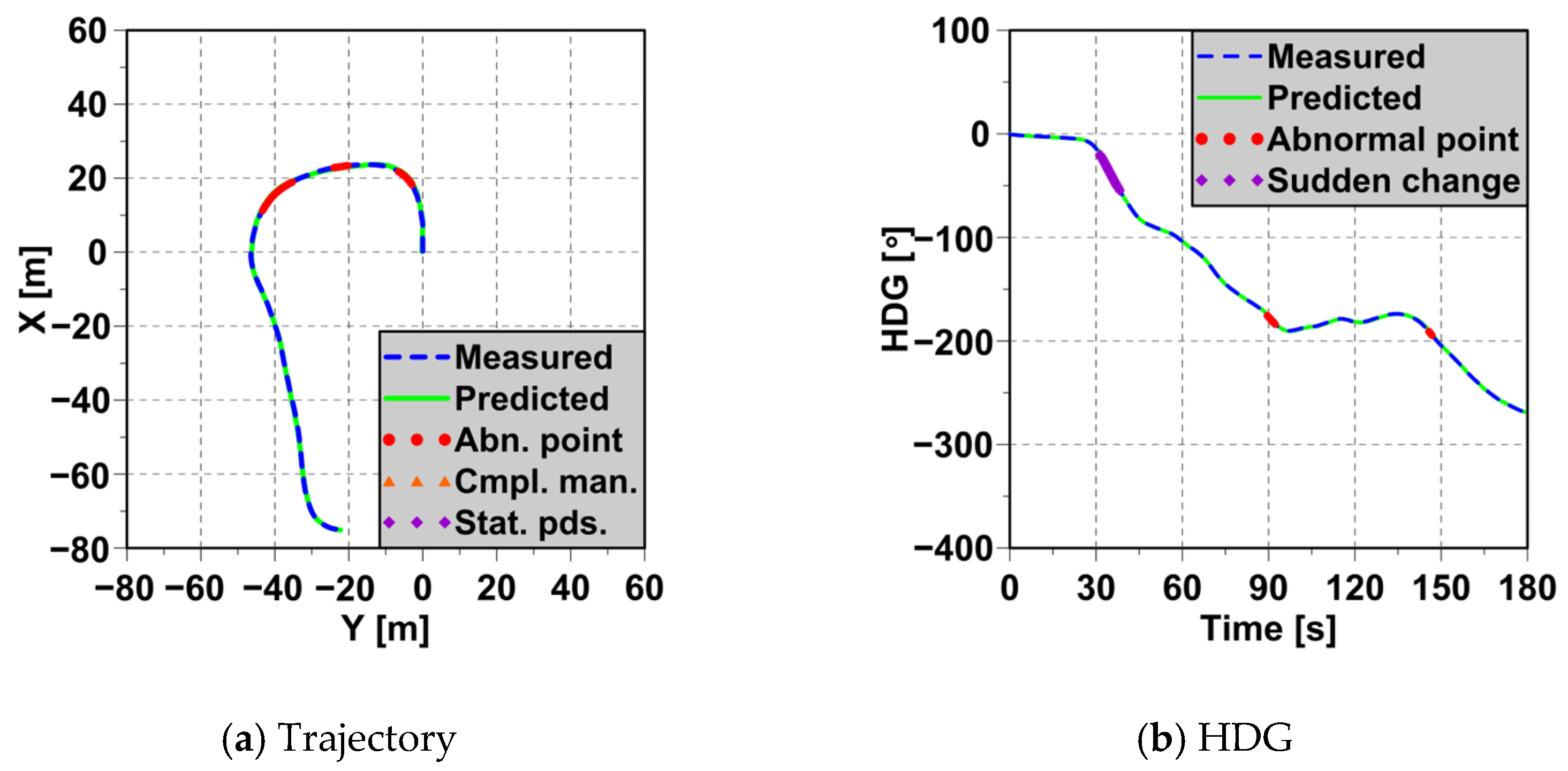

4.3. Detection of Abnormal Ship Behaviors

4.4. Evaluation Based on Abnormal Behavior Criteria

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, B.R.; Park, Y.K. ArcGIS based Analysis of Multiple Accident Areas Caused by Marine Plastic Litter in Republic of Korea. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2022, 33, 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.W.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Z. Data-driven methods for detection of abnormal ship behavior: Progress and trends. Ocean Eng. 2023, 271, 113673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksciuk, J.; Kuhlemann, S.; Tierney, K.; Koberstein, A. Uncertainty in maritime ship routing and scheduling: A Literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 308, 499–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.; Lagdami, K.; Mejia, M. Enhancing maritime safety: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in the domestic ferry sector. Marit. Technol. Res. 2024, 6, 268911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Song, D.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, H. Design and Motion Performance Analysis of Turbulent AUV Measuring Platform. Sensors 2022, 22, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Long, C.; Yang, X.; Deng, M. Abnormal Ship Behavior Detection Based on AIS Data. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ren, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, D. Research Progress on Ship Anomaly Detection Based on Big Data. In Proceedings of the IEEE 11th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 16–18 October 2020; pp. 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, H.; Teixeira, A.P.; Guedes Soares, C. Data mining approach to shipping route characterization and anomaly detection based on AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2020, 198, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radon, A.N.; Wang, K.; Glasser, U.; Wehn, H.; Westwell-Roper, A. Contextual verification for false alarm reduction in maritime anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 29 October–1 November 2015; pp. 1123–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Wang, S. Study of Data-Driven Methods for Vessel Anomaly Detection Based on AIS Data. Smart Innov. Syst. Tecnol. 2019, 149, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Iphar, C.; Ray, C.; Napoli, A. Data integrity assessment for maritime anomaly detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 147, 113219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Teixeira, A.P.; Guedes Soares, C. A framework for ship abnormal behavior detection and classification using AIS data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 247, 110105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Lian, S.; Zhang, D.; Lang, X.; Rong, H.; Mao, W.; Zhang, M. A machine learning method for the recognition of ship behavior using AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2024, 315, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Matwin, S. Anomaly detection for maritime navigation based on probalility density function of error of reconstruction. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 32, 20220270. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z. A Novel Hybrid Approach for Detecting Abnormal Vessel Behavior in Maritime Traffic. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Xi’an, China, 4–6 August 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.T.; Yang, H. Ship-Route Prediction Based on a Long Short-Term Memory Network Using Port-to-Port Trajectory Data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.W.; Hu, K.; Liang, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, D. QSD-LSTM: Vessel trajectory prediction using long short-term memory with quaternion ship domain. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 136, 103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qiang, H.; Peng, X. Vessel Trajectory Prediction Using Vessel Influence Long Short-Term Memory with Uncertainty Estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Fu, Y. Ship Trajectory Prediction Based on Attention in Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Science, Computer Technology and Transportation (ISCTT), Shenyang, China, 13–15 November 2020; pp. 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Tang, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhang, G. Short-term ship motion attitude prediction based on LSTM and GPR. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 118, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Khan, J.; Lee, E.; Hussain, S.; Balobaid, A.S.; Aburasain, R.Y.; Kim, K. An Efficient Long Short-Term Memory and Gated Recurrent Unit Based Smart Vessel Trajectory Prediction Using Automatic Identification System Data. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 81, 1789–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xinya, P.; Zexuan, D.; Jiansen, Z. An Approach to Ship Behavior Prediction Based on AIS and RNN Optimization Model. Int. J. Transp. Eng. Technol. 2020, 6, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsing, K.; Roepert, L.; Bauer, J.; Wehrle, K. Anomaly Detection in Maritime AIS Tracks: A Review of Recent Approaches. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Ou, M.; Liang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, M. Abnormal Detection Method of Transship Based on Marine Target Spatio-Temporal Data. J. Internet Technol. 2023, 24, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyasayumranani, W.; Hwang, T.; Hwang, T.; Youn, I.H. Anomaly detection model of small-scaled ship for maritime autonomous surface ships’ operation. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2022, 6, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hirayama, K.; Ren, H.; Wang, D.; Li, H. Ship Anomalous Behavior Detection Using Clustering and Deep Recurrent Neural Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Shu, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, W.; Wang, J. Ship Anomalous Behavior Detection in Port Waterways Based on Text Similarity and Kernel Density Estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. A mathematical investigation on the distance-preserving property of an equidistant cylindrical projection. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Architecture | 10 Epochs | 20 Epochs | 30 Epochs | 40 Epochs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [128] | 1.317 × 10−4 | 5.193 × 10−5 | 3.765 × 10−5 | 3.435 × 10−5 |

| [128,128] | 3.697 × 10−5 | 2.510 × 10−5 | 3.002 × 10−5 | 1.548 × 10−5 |

| [128,128,128] | 4.465 × 10−5 | 3.678 × 10−5 | 3.625 × 10−5 | 4.752 × 10−5 |

| [128,128,128,128] | 4.575 × 10−5 | 9.636 × 10−5 | 1.041 × 10−4 | 1.155 × 10−4 |

| Threshold Value | All Points in Data | Abnormal Points | Abnormal Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory | |||

| 1SD = 0.136 m | 1790 | 1056 | 58.994% |

| 2SD = 0.272 m | 427 | 23.855% | |

| 3SD = 0.408 m | 183 | 10.223% | |

| HDG | |||

| 1SD = 0.296° | 1790 | 605 | 33.799% |

| 1SD = 0.592° | 253 | 14.134% | |

| 3SD = 0.888° | 109 | 6.089% | |

| COG | |||

| 1SD = 2.568° | 1790 | 377 | 21.061% |

| 2SD = 5.128° | 121 | 6.760% | |

| 3SD = 7.692° | 44 | 2.458% | |

| SOG | |||

| 1SD = 0.045 m/s | 1790 | 858 | 47.933% |

| 2SD = 0.090 m/s | 272 | 15.196% | |

| 3SD = 0.135 m/s | 85 | 4.749% | |

| Item | Threshold Value | Abnormal Points |

|---|---|---|

| Trajectory | ||

| Abnormal deviation | 0.408 m | 183 |

| Complex maneuver | 13.041°/s | 0 |

| Stationary period | 1 m, 5 s | 0 |

| HDG | ||

| Sudden change | 0.471° | 65 |

| COG | ||

| Sudden change | 7.113° | 32 |

| SOG | ||

| Sudden acceleration | 0.0723 m/s | 12 |

| Sudden deceleration | 6 |

| Criteria | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Sudden speed changes | Satisfied |

| Unusual course changes | Satisfied |

| Extended stationary periods | Unsatisfied |

| Deviation from the expected route | Satisfied |

| Complex maneuvers | Unsatisfied |

| Track continuity issues | Unsatisfied |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vu, H.T.; Mai, V.T.; Nguyen, T.T.D.; Yoon, H.K.; Choi, H. A Hybrid Statistical and Neural Network Method for Detecting Abnormal Ship Behavior Using Leisure Boat Sea Trial Data in a Marina Port. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122391

Vu HT, Mai VT, Nguyen TTD, Yoon HK, Choi H. A Hybrid Statistical and Neural Network Method for Detecting Abnormal Ship Behavior Using Leisure Boat Sea Trial Data in a Marina Port. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122391

Chicago/Turabian StyleVu, Hoang Thien, Van Thuan Mai, Thi Thanh Diep Nguyen, Hyeon Kyu Yoon, and Hujae Choi. 2025. "A Hybrid Statistical and Neural Network Method for Detecting Abnormal Ship Behavior Using Leisure Boat Sea Trial Data in a Marina Port" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122391

APA StyleVu, H. T., Mai, V. T., Nguyen, T. T. D., Yoon, H. K., & Choi, H. (2025). A Hybrid Statistical and Neural Network Method for Detecting Abnormal Ship Behavior Using Leisure Boat Sea Trial Data in a Marina Port. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122391