A Matheuristic Framework for Behavioral Segmentation and Mobility Analysis of AIS Trajectories Using Multiple Movement Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A behavior-based segmentation approach is introduced using speed, acceleration, and turning rate, where turning rate captures geometric variation without relying on distance thresholds. Each behavioral attribute is discretized independently using Jenks algorithm, which reduces interference among attributes and provides interpretable feature labels for subsequent behavioral analysis. Furthermore, key feature points, identified by label differences between consecutive trajectory points, narrow the candidate set of segmentation boundaries and thereby accelerate the subsequent optimization process.

- To enhance generalizability across vessels of varying sizes and to adapt to the noisy and irregular characteristics of AIS data, the MDL principle is employed as the segmentation objective. This formulation ensures consistent multi-attribute segmentation with movement features normalized by their respective maximum values and enables the discovery of diverse navigation patterns.

- A MFSS algorithm is developed to achieve an effective balance between segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency. The framework incorporates a segmentwise reformulation of the problem to linearize MDL terms and mitigate sensitivity to isolated point fluctuations, a random fixed set for global exploration, a mixed-integer programming (MIP) solver for local refinement, and the GRTD initialization to generate high-quality candidate solutions.

2. Related Work

3. Matheuristic-Based Behavioral Segmentation

3.1. Basic Definitions

- Feature Dissimilarity : The Euclidean distance between two points in the normalized feature space:

- Segment Cohesiveness : The behavioral homogeneity within a segment relative to its centroid:

- Inter-segment Distinctness : The dissimilarity between adjacent segment centroids:

3.2. AIS Data Preprocessing

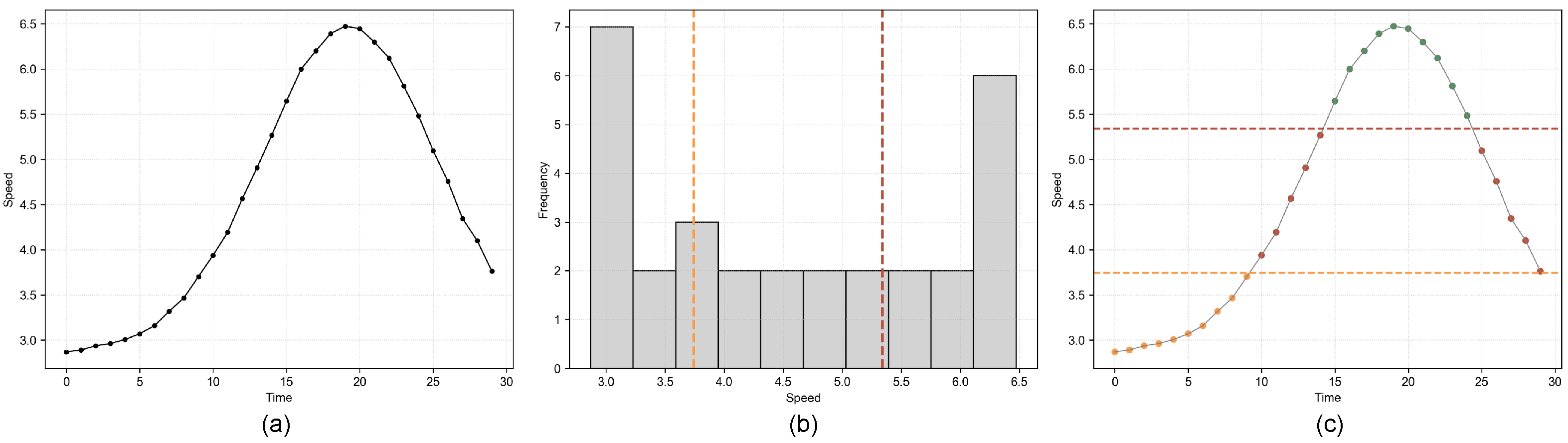

3.3. Movement Feature Generation, Decomposition and Key Feature Point Extraction

3.4. Problem Description

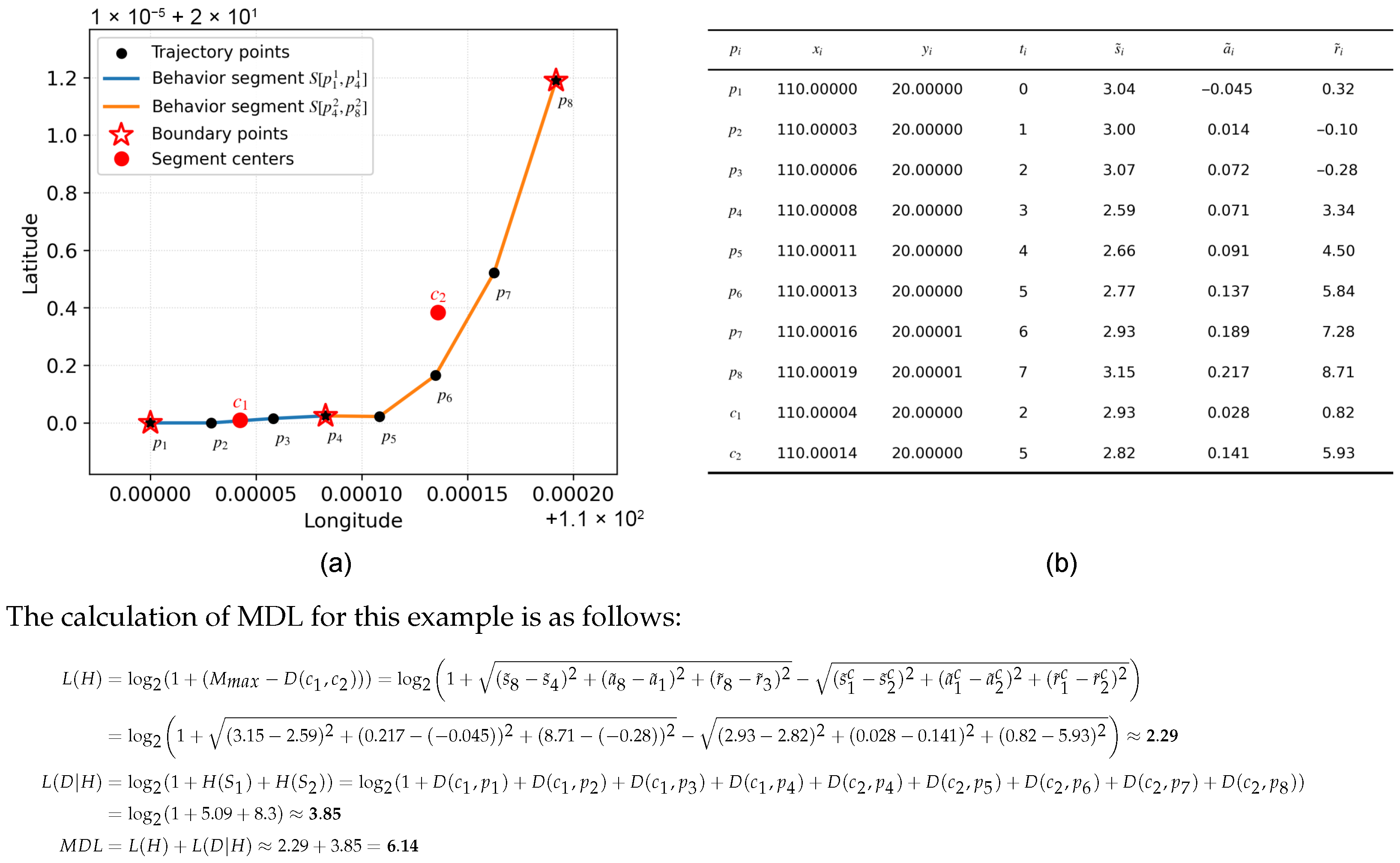

3.4.1. The MDL Principle

3.4.2. Mathematical Model

3.5. Matheuristic Fixed Set Search

3.5.1. Problem Reformulation

3.5.2. Solution Initialization

| Algorithm 1 GRTD: Greedy Randomized Top-Down Initialization. |

|

3.5.3. Fixed Set Generation

3.5.4. Population Evolution

| Algorithm 2 MFSS: Matheuristic Fixed Set Search. |

|

4. Experiment and Results Analysis

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Baselines and Experimental Setup

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

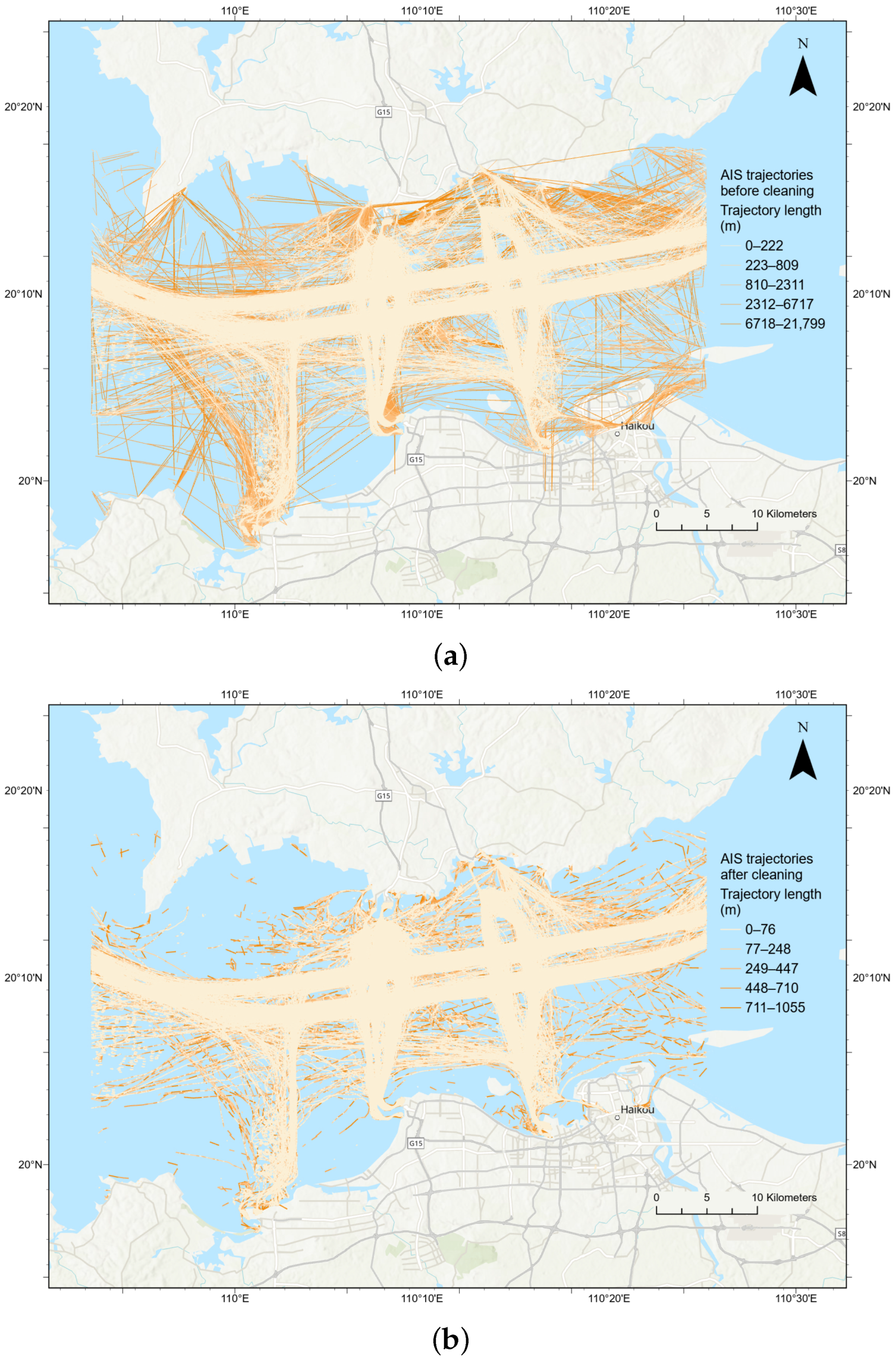

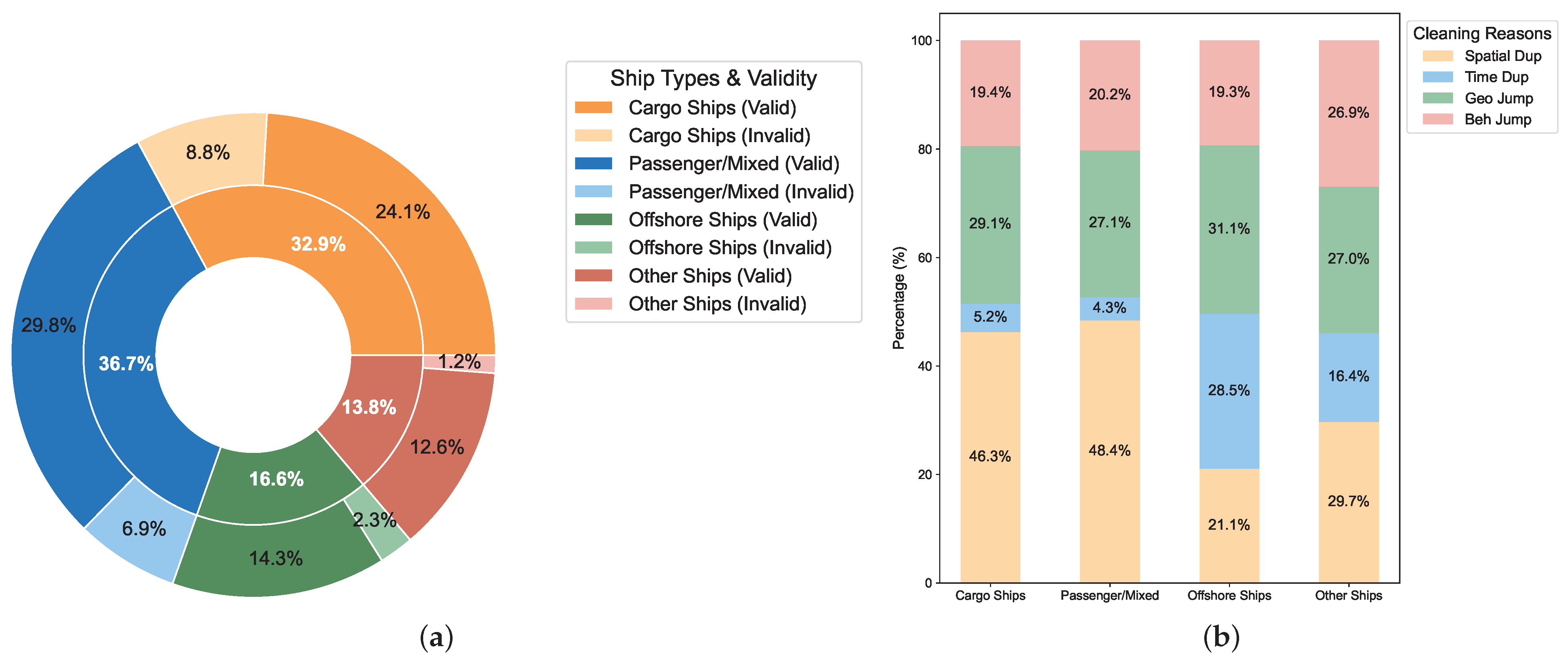

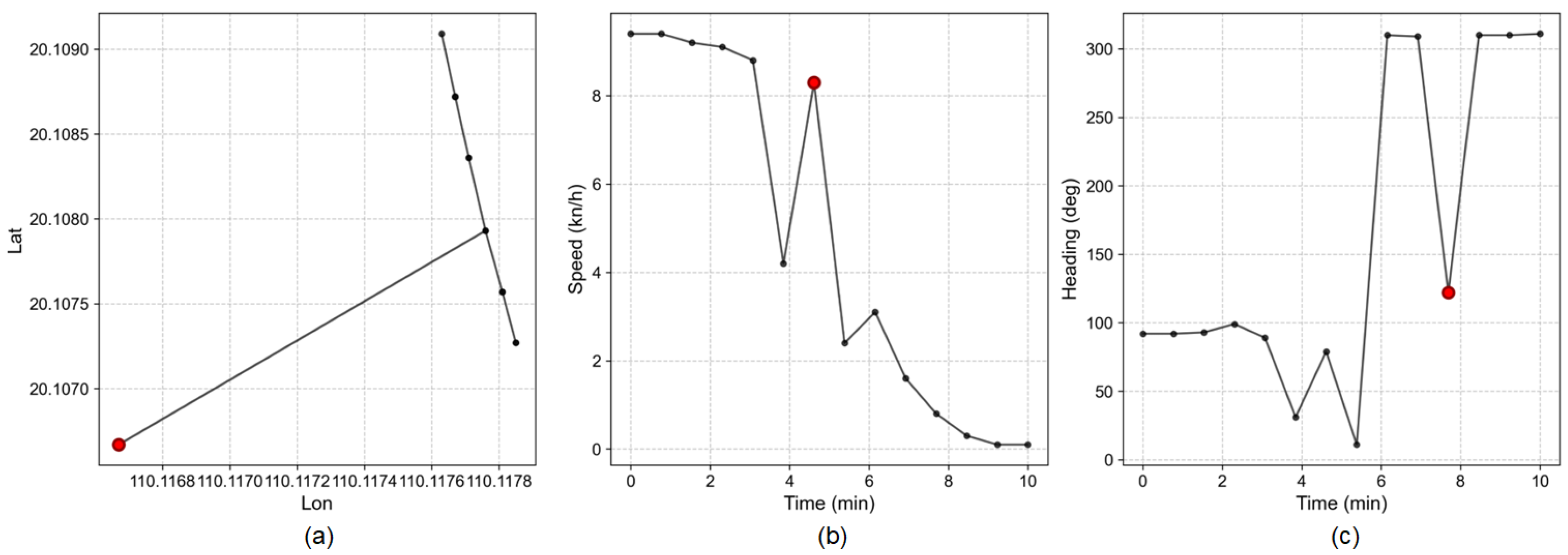

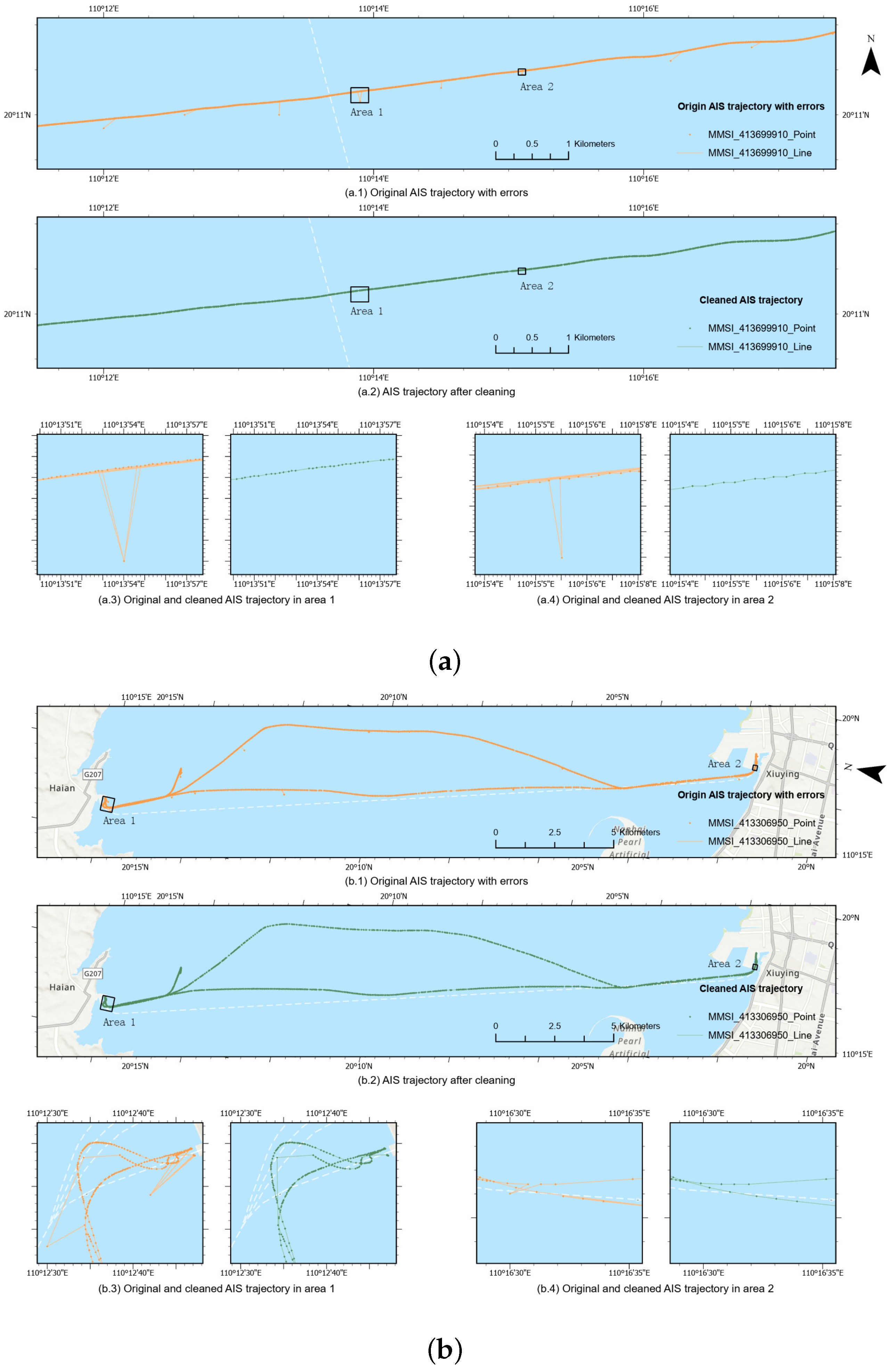

4.4. Data Preprocessing Results

4.5. Segmentation Results

4.5.1. Evaluation Analysis

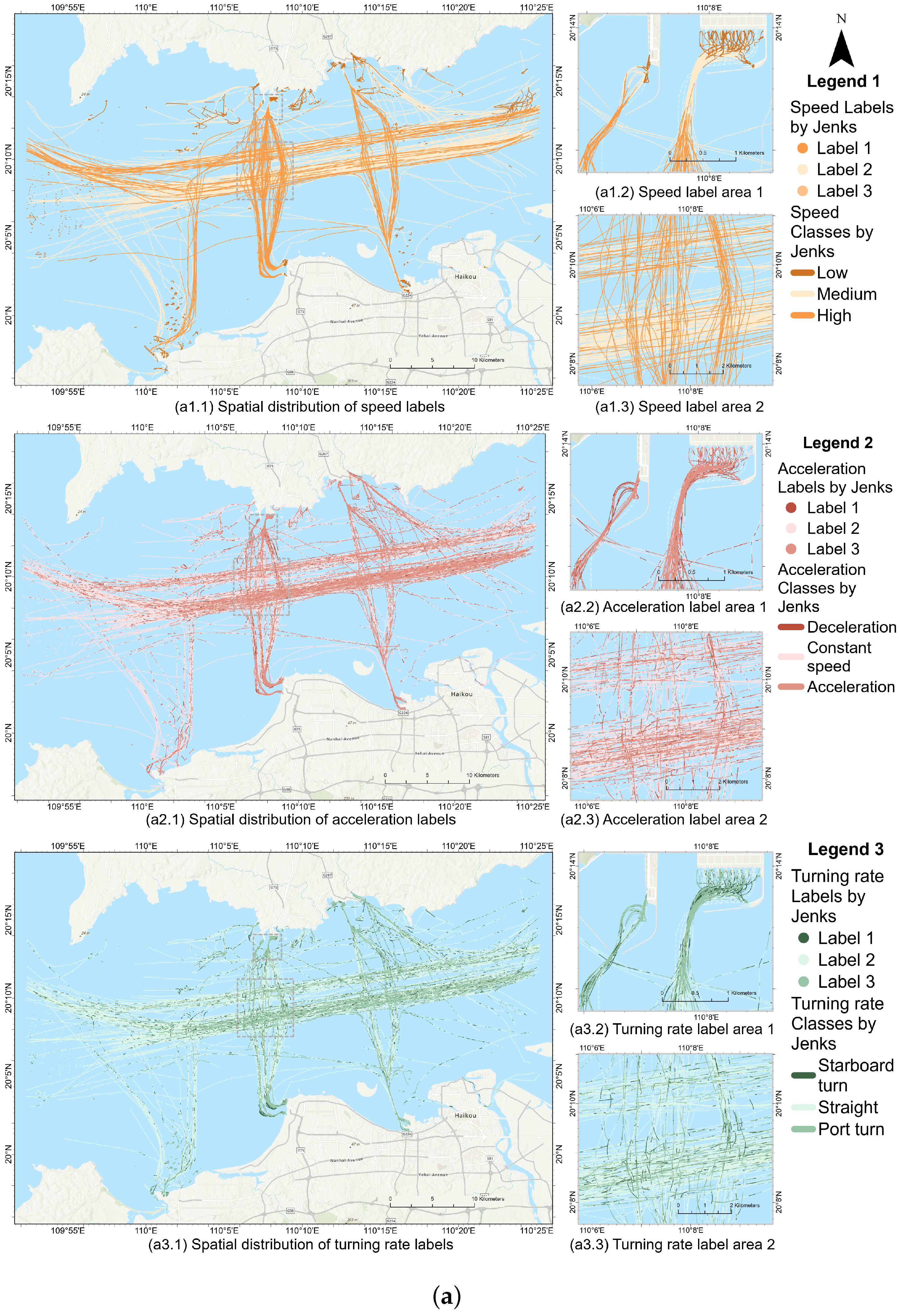

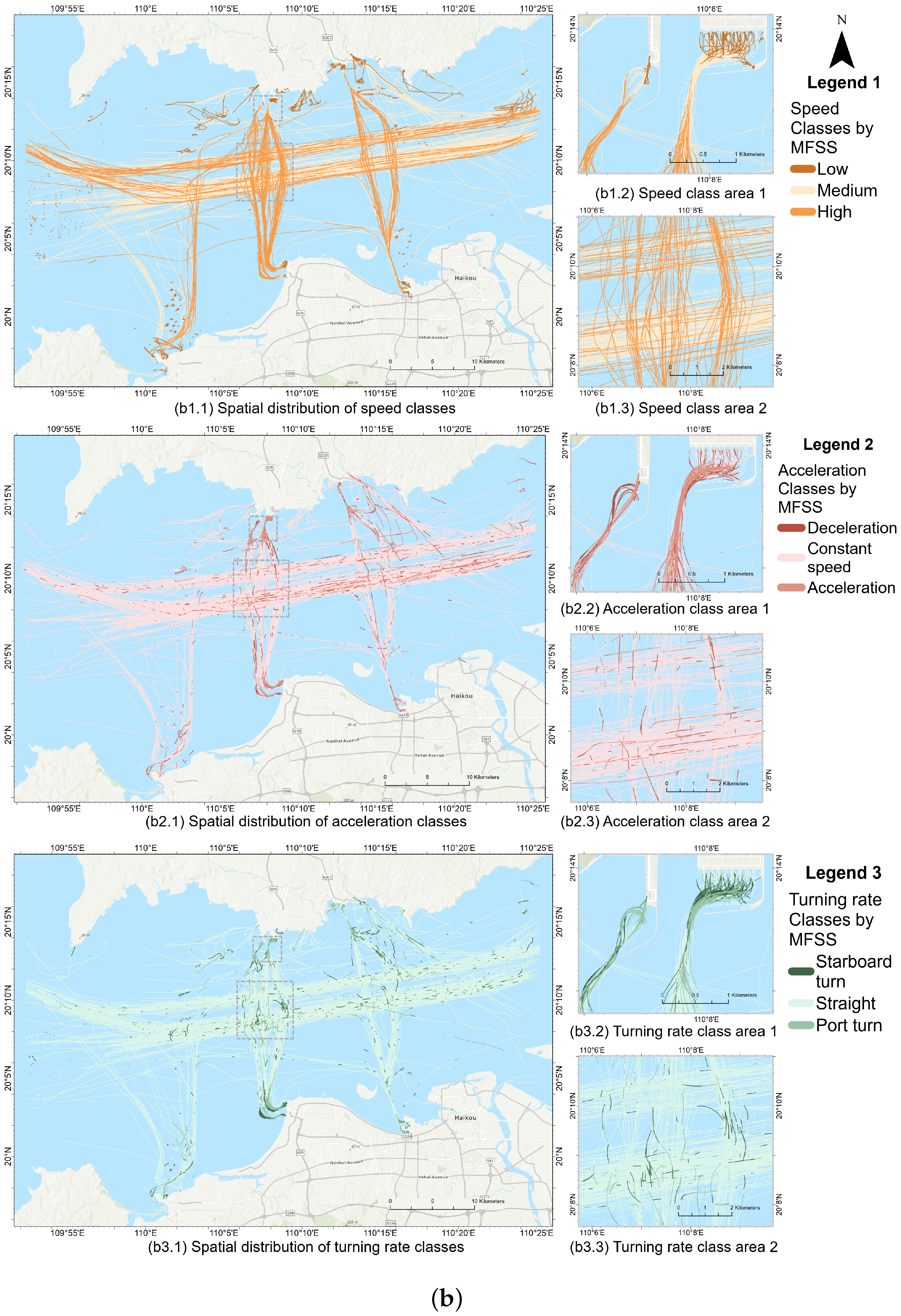

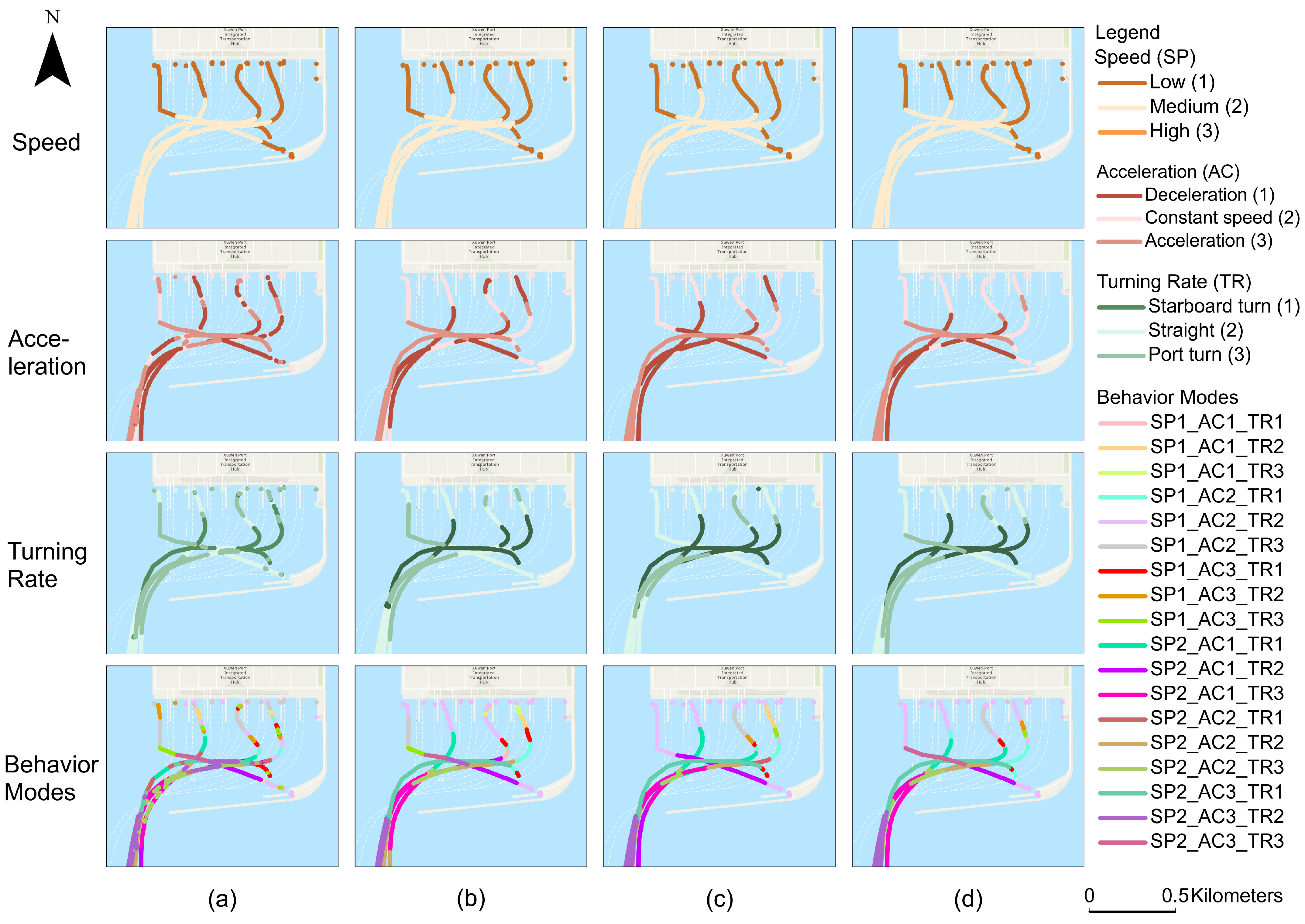

4.5.2. Trajectory Movement Patterns

4.5.3. Trajectory Segment Behaviors

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis

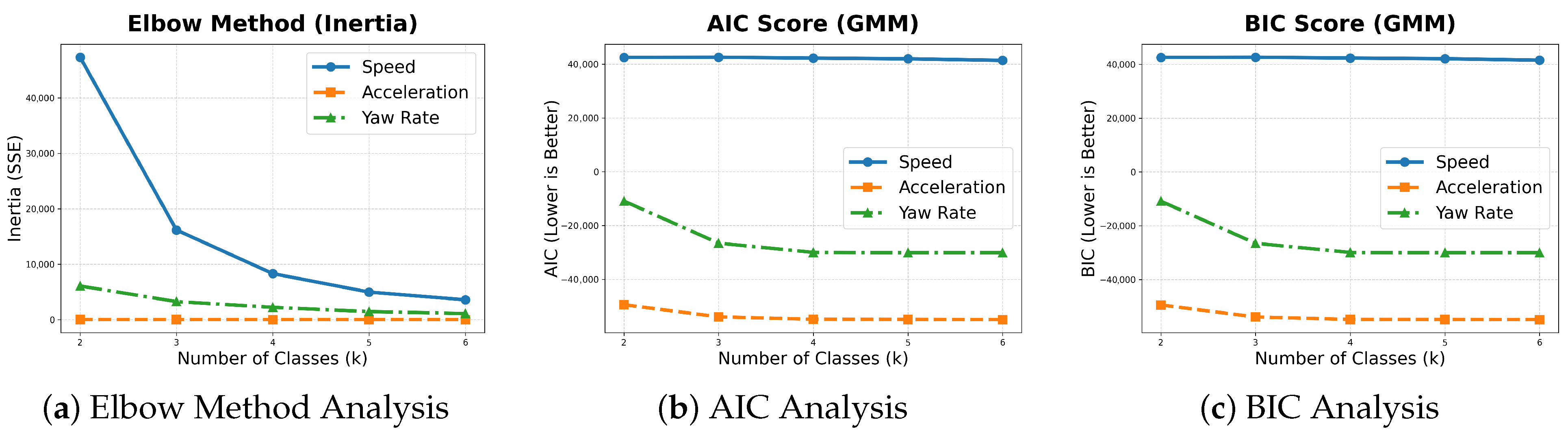

4.6.1. Feature Class Selection

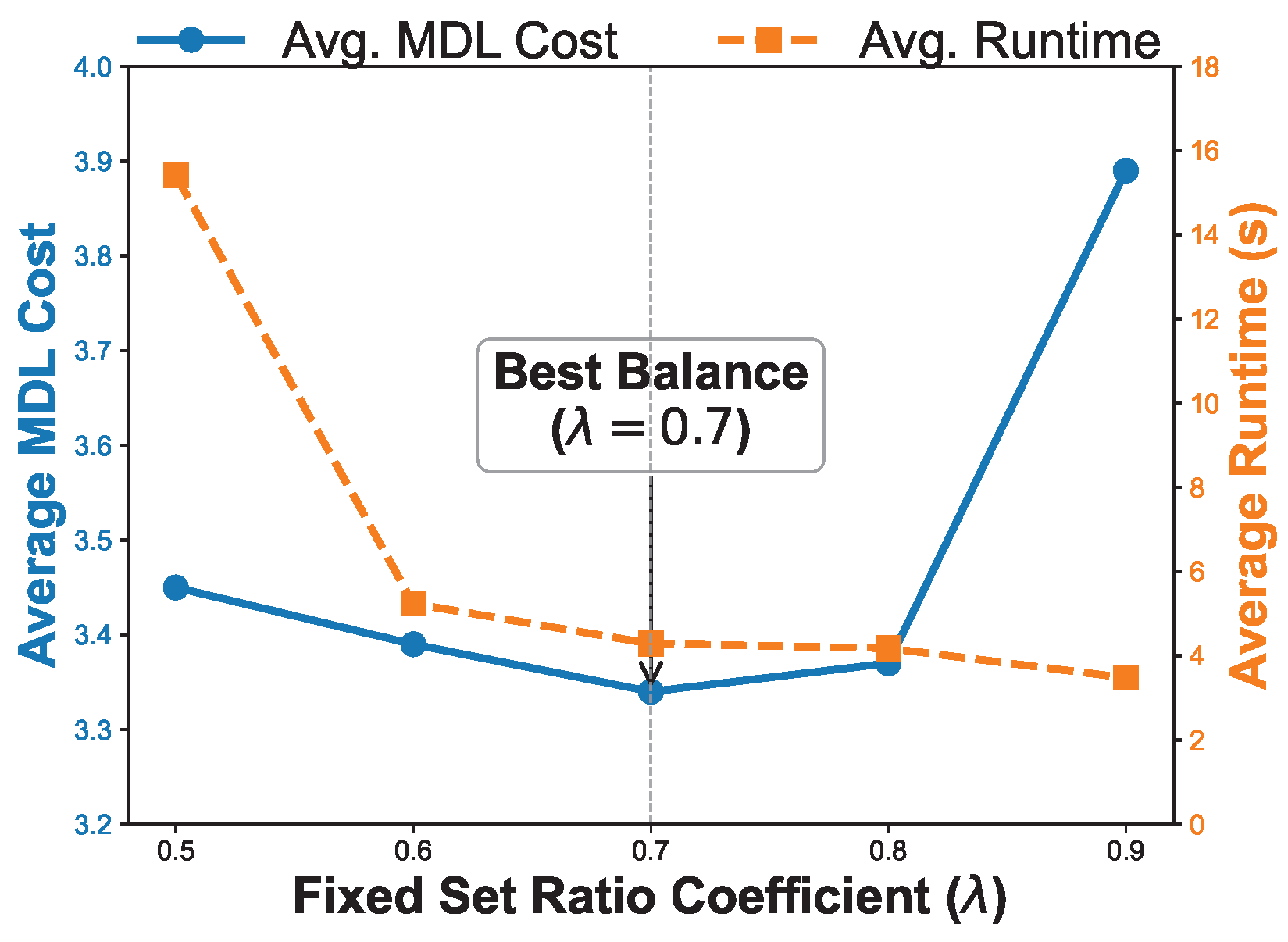

4.6.2. Parameter Selection and Justification of MFSS

4.6.3. Problem Complexity and Computational Efficiency

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample of Original AIS Trajectory Data

| Static Information | Dynamic Information | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSI | Ship Type | W (m) | L (m) | Lon | Lat | Spd (kn) | Hdg (°) | Crs (°) | Nav. Status * | Timestamp | |

| 413508170 | Chemical/Oil tanker | 14 | 89 | 110.23489 | 20.16195 | 7.3 | 78 | 76.6 | UWE | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

| 413210640 | Container ship | 24 | 129 | 110.26017 | 20.06549 | 7.0 | 302 | 341.1 | UWE | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

| 413232470 | Passenger ship | 21 | 128 | 110.13545 | 20.22967 | 3.3 | 61 | 50.3 | UWE | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

| 412522250 | Ro-Ro passenger ship | 22 | 165 | 110.11448 | 20.21002 | 11.3 | 16 | 17.4 | UWE | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

| 413358570 | Bulk carrier | 16 | 99 | 110.15248 | 20.17945 | 10.4 | 511 | 263.3 | UWE | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

| 413523230 | Passenger ship | 20 | 123 | 110.13617 | 20.23290 | 0.0 | 0 | 21.8 | MRD | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

| 412000002 | Fishing vessel | 5 | 20 | 110.23166 | 20.27136 | 5.8 | 511 | 111.0 | UNK | 2025/08/31 00:00:08 | |

Appendix B. Parameter Settings of the MFSS Algorithm

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Population size (number of solutions maintained in the pool) | 20 | |

| Size of randomly chosen subset for similarity evaluation | 8 | |

| Maximum number of stagnation iterations before parameter update | 10 | |

| Initial size of fixed segment set (adaptive to m) | ||

| Adjustment rate of fixed set size when stagnation occurs | 0.95 | |

| Initial time limit (s) for the MIP solver (adaptive to n) | ||

| Adjustment rate of MIP solver time limit during search | 1.2 | |

| Overall runtime limit of the MFSS process (adaptive to n) | ||

| Stall limit: maximum consecutive iterations without improvement | 50 |

| 1 | Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/safety/pages/ais.aspx (accessed on 1 December 2025). |

| 2 | Available online: http://www.hifleet.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2025). |

References

- Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y. A novel ship trajectory clustering analysis and anomaly detection method based on AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.W.; Zhu, Y.S.; Zhang, J.F.; He, Y.K.; Yan, K.; Yan, B.R. A novel MP-LSTM method for ship trajectory prediction based on AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2021, 228, 108956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L. A big data analytics method for the evaluation of maritime traffic safety using automatic identification system data. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Rong, H.; Soares, C.G. Shipping route modelling of AIS maritime traffic data at the approach to ports. Ocean Eng. 2023, 289, 115868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.K.; Shi, G.Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Zhao, Z.W.; Wu, Z.L. Data-driven based automatic maritime routing from massive AIS trajectories in the face of disparity. Ocean Eng. 2018, 155, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wan, C.; Liu, Z. AIS data-driven approach to estimate navigable capacity of busy waterways focusing on ships entering and leaving port. Ocean Eng. 2020, 218, 108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dong, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L.; Liu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, C. AIS data-driven analysis for identifying cargo handling events in international trade tankers. Ocean Eng. 2025, 317, 120016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Trajectory data mining: An overview. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. TIST 2015, 6, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakian, Z.; Mesgari, M.S.; Weibel, R. A feature extraction based trajectory segmentation approach based on multiple movement parameters. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 88, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, P.; Imfeld, S.; Weibel, R. Discovering relative motion patterns in groups of moving point objects. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2005, 19, 639–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, L.O.; Bogorny, V.; Kuijpers, B.; de Macedo, J.A.F.; Moelans, B.; Vaisman, A. A model for enriching trajectories with semantic geographical information. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual ACM International Symposium on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Seattle WA, USA, 7–9 November 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, A.T.; Bogorny, V.; Kuijpers, B.; Alvares, L.O. A clustering-based approach for discovering interesting places in trajectories. In Proceedings of the ACM symposium on Applied computing, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, 16–20 March 2008; pp. 863–868. [Google Scholar]

- Soares Júnior, A.; Moreno, B.N.; Times, V.C.; Matwin, S.; Cabral, L.d.A.F. GRASP-UTS: An algorithm for unsupervised trajectory segmentation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminikhanghahi, S.; Cook, D.J. A survey of methods for time series change point detection. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2017, 51, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchin, M.; Driemel, A.; Van Kreveld, M.J.; Sacristán, V. Segmenting trajectories: A framework and algorithms using spatiotemporal criteria. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2011, 3, 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, A.; Cai, Y.; Ai, B. An asynchronous trajectory matching method based on piecewise space-time constraints. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 224712–224728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsea, C.W.; Franklin, J.L. Atlantic hurricane database uncertainty and presentation of a new database format. Mon. Weather Rev. 2013, 141, 3576–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, M.; Etemad, Z.; Soares, A.; Bogorny, V.; Matwin, S.; Torgo, L. Wise sliding window segmentation: A classification-aided approach for trajectory segmentation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 33rd Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Canadian AI 2020, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 13–15 May 2020; Proceedings 33. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 208–219. [Google Scholar]

- Junior, A.S.; Times, V.C.; Renso, C.; Matwin, S.; Cabral, L.A. A semi-supervised approach for the semantic segmentation of trajectories. In Proceedings of the 19th IEEE international conference on mobile data management (MDM), Aalborg, Denmark, 26–28 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H. An adaptive trajectory segmentation and simplification algorithm based on vessel behavioral features. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, M.; Soares, A.; Etemad, E.; Rose, J.; Torgo, L.; Matwin, S. SWS: An unsupervised trajectory segmentation algorithm based on change detection with interpolation kernels. GeoInformatica 2021, 25, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, S.; Laube, P.; Weibel, R. Movement similarity assessment using symbolic representation of trajectories. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 26, 1563–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wu, H.; Yin, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhang, R. Vessel trajectory segmentation: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications, Tianjin, China, 17 April 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 166–180. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, D.H.; Peucker, T.K. Algorithms for the reduction of the number of points required to represent a digitized line or its caricature. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 1973, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shi, G.; Li, W.; Jiang, D. A direction-preserved vessel trajectory compression algorithm based on open window. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, E.; Chu, S.; Hart, D.; Pazzani, M. An online algorithm for segmenting time series. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, San Jose, CA, USA, 29 November–2 December 2001; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Xu, Z.; Qiu, M.; Wang, X.; Han, T. Noise filtering, trajectory compression and trajectory segmentation on GPS data. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), Nagoya, Japan, 23–25 August 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Amigo, D.; Pedroche, D.S.; García, J.; Molina, J.M. Segmentation optimization in trajectory-based ship classification. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 59, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, L.A.; Vidal, E. Warped k-means: An algorithm to cluster sequentially-distributed data. Inf. Sci. 2013, 237, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birant, D.; Kut, A. ST-DBSCAN: An algorithm for clustering spatial–temporal data. Data Knowl. Eng. 2007, 60, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ji, M.; Wang, J. T-DBSCAN: A Spatiotemporal Density Clustering for GPS Trajectory Segmentation. Int. J. Online Eng. 2014, 10, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, J. Modeling by shortest data description. Automatica 1978, 14, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Han, J.; Whang, K.Y. Trajectory clustering: A partition-and-group framework. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Beijing, China, 12–14 June 2007; pp. 593–604. [Google Scholar]

- Etemad, M.; Júnior, A.S.; Hoseyni, A.; Rose, J.; Matwin, S. A Trajectory Segmentation Algorithm Based on Interpolation-based Change Detection Strategies. In Proceedings of the EDBT/ICDT Workshops, Lisbon, Portugal, 26 March 2019; Volume 31, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Z.; Xie, X.; Ma, W.Y. Recommending friends and locations based on individual location history. ACM Trans. Web TWEB 2011, 5, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, X.; Ching, W.K.; Dan, R.; Li, W.K.; Zhang, Z. GPS trajectory data segmentation based on probabilistic logic. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2018, 103, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Gao, M.; Wu, T. Extracting stops from noisy trajectories: A sequence oriented clustering approach. ISPRS Int. J.-Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; He, G.; Long, Y. A semantics-based trajectory segmentation simplification method. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2021, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Xiang, J. Vessel pattern recognition using trajectory shape feature. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Beijing, China, 4–6 December 2021; pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Wen, R.; Zhang, A.N.; Yang, D. Vessel movement analysis and pattern discovery using density-based clustering approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on big data (Big Data), Washington, DC, USA, 5–8 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; 2016, pp. 3798–3806. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, J.A.M.; Times, V.C.; Oliveira, G.; Alvares, L.O.; Bogorny, V. DB-SMoT: A direction-based spatio-temporal clustering method. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Conference Intelligent Systems, London, UK, 7–9 July 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zimányi, E.; Sakr, M.; Torp, K. Semantic segmentation of ais trajectories for detecting complete fishing activities. In Proceedings of the 23rd IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM), Paphos, Cyprus, 6–9 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.D.; Winter, S. Automated urban travel interpretation: A bottom-up approach for trajectory segmentation. Sensors 2016, 16, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, M.; Han, J.; Ji, G.; Liu, X. Efficient semantic enrichment process for spatiotemporal trajectories. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 4488781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, L.; Feng, J.; Wang, X. Semantic trajectory segmentation based on change-point detection and ontology. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 2361–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, F.; Peng, X.; Zhan, W.; Sui, Z. Semantic modelling of ship behavior in harbor based on ontology and dynamic bayesian network. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cai, Z.; Yu, W.; Sun, W. Trajectory data compression algorithm based on ship navigation state and acceleration variation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharghabi, S.; Ding, Y.; Yeh, C.C.M.; Kamgar, K.; Ulanova, L.; Keogh, E. Matrix profile VIII: Domain agnostic online semantic segmentation at superhuman performance levels. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–21 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Dong, S. Application of artificial intelligence in an unsupervised algorithm for trajectory segmentation based on multiple motion features. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 9540944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Lai, K.h.; Qian, W. Semantic recognition of ship motion patterns entering and leaving port based on topic model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wen, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, M. Mobility pattern analysis of ship trajectories based on semantic transformation and topic model. Ocean Eng. 2020, 201, 107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Lv, J. Research on geographical environment unit division based on the method of natural breaks (Jenks). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, P.D. The Minimum Description Length Principle; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, R.; Tuba, M.; Voß, S. Fixed set search applied to the traveling salesman problem. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Hybrid Metaheuristics, Málaga, Spain, 20–22 June 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, R.; Voß, S. Fixed set search matheuristic applied to the knapsack problem with forfeits. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 168, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Hammer, P.L.; Simeone, B. Quadratic Knapsack Problems. Math. Program. 1980, 12, 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, R.; Voß, S. Solving the Quadratic Knapsack Problem Using GRASP. In Metaheuristics for Machine Learning: New Advances and Tools; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lalla-Ruiz, E.; Shi, X.; Voß, S. The waterway ship scheduling problem. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 60, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lon (°) | Lat (°) | Speed (kn) | Course (°) | Heading (°) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Duplicate Records (MMSI: 100661111): Identical information repeated at adjacent timestamps | |||||

| 110.06675 | 20.12604 | 6.8 | 68.0 | 68.4 | 2025/8/31 02:12:17 |

| 110.07040 | 20.12759 | 3.4 | 68.0 | 68.3 | 2025/8/31 02:14:26 |

| 110.07040 | 20.12759 | 3.4 | 68.0 | 68.3 | 2025/8/31 02:14:27 |

| 110.07040 | 20.12759 | 3.4 | 68.0 | 68.3 | 2025/8/31 02:14:29 |

| 110.07394 | 20.12876 | 3.2 | 78.0 | 78.4 | 2025/8/31 02:16:38 |

| (b) Temporal Conflicts (MMSI: 101103668): Multiple distinct points recorded at the exact same timestamp | |||||

| 110.04914 | 20.13507 | 3.7 | 74.0 | 74.9 | 2025/8/30 23:36:02 |

| 110.04957 | 20.13517 | 3.8 | 74.0 | 74.6 | 2025/8/30 23:37:02 |

| 110.05036 | 20.13534 | 3.7 | 78.0 | 78.5 | 2025/8/30 23:37:02 |

| 110.04986 | 20.13523 | 3.7 | 78.0 | 78.0 | 2025/8/30 23:37:02 |

| 110.04970 | 20.13520 | 3.7 | 78.0 | 78.4 | 2025/8/30 23:37:02 |

| 110.05103 | 20.13555 | 3.8 | 77.0 | 77.6 | 2025/8/30 23:38:02 |

| Method | DBI | SC | CHI | ISV | ESV | AP (%) | AC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFSS | 1.685 | 0.120 | 12.031 | 0.274 | 0.786 | 70.547 | 98.881 |

| SWS | 2.578 | 0.085 | 6.335 | 0.355 | 0.673 | 70.615 | 98.915 |

| TDS | 1.973 | 0.064 | 4.911 | 0.370 | 0.767 | 70.287 | 99.163 |

| Jenks | 7.340 | −0.414 | 1.938 | 0.213 | 0.251 | 80.865 | 86.353 |

| Points | Cplex | MFSS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDL | Runtime | Avg MDL | Best MDL | Avg Gap | Best Gap | Runtime | ||

| 50 | 3.11 | 109.03 | 3.11 | 3.11 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 4.29 | |

| 100 | 4.11 | 600.00 | 3.88 | 3.85 | −5.60% | −6.33% | 28.15 | |

| 200 | 4.99 | 600.00 | 4.74 | 4.60 | −5.01% | −7.81% | 139.14 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Voß, S. A Matheuristic Framework for Behavioral Segmentation and Mobility Analysis of AIS Trajectories Using Multiple Movement Features. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122393

Wu F, Liu Y, Li R, Voß S. A Matheuristic Framework for Behavioral Segmentation and Mobility Analysis of AIS Trajectories Using Multiple Movement Features. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122393

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Fumi, Yangming Liu, Ronghui Li, and Stefan Voß. 2025. "A Matheuristic Framework for Behavioral Segmentation and Mobility Analysis of AIS Trajectories Using Multiple Movement Features" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122393

APA StyleWu, F., Liu, Y., Li, R., & Voß, S. (2025). A Matheuristic Framework for Behavioral Segmentation and Mobility Analysis of AIS Trajectories Using Multiple Movement Features. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122393