1. Introduction

Among the many challenges of autonomous navigation in maritime environments, the need for efficient and safe autonomous obstacle avoidance stands out. For an autonomous vessel to operate reliably, its perception system must identify, in real time, the position and motion of obstacles and other vessels, enabling the control system to perform precise maneuvers to prevent collisions.

The ongoing growth in the use of USVs (Unmanned Surface Vessels) in Brazilian waters has led to updates of the national regulatory framework. A notable result is NORMAM-205 (Maritime Authority Standards for Autonomous Vessels), the standard issued by the Brazilian Navy that governs autonomous craft. NORMAM-205 states that an autonomous vessel must have “the capability to interpret on-board sensor data in a manner adequate to ensure the safety of the vessel itself and of other vessels with which it may interact during navigation, in compliance with COLREGs and other international conventions and codes” (NORMAM-205; free translation) [

1].

The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs) lay down the rules that govern safe navigation, playing a role similar to traffic regulations on land [

2]. This set of guidelines is essential for ensuring safety and order at sea. Consequently, an autonomous ship must not only monitor its surroundings continuously, but also robustly incorporate the principles established by the COLREGs into its decision-making and trajectory-planning algorithms.

This research implements and experimentally validates Collision Avoidance algorithms for autonomous vessels, with special emphasis on verifying their conformity to the COLREGs. The objective is to enhance USVs ability to avoid obstacles, ensuring safe and reliable autonomous maneuvers.

This work proposes the following:

- (1)

To implement three COLREGs-compliant collision-avoidance algorithms on a real USV: Behavior-based Collision Avoidance, Modified Velocity Obstacles (VO) Algorithm and an Modified A* path-planning algorithm.

- (2)

To perform a comparative field evaluation of these algorithms using consistent scenarios and metrics.

2. Overview of Collision-Avoidance Strategies Considered

This section provides an overview of the collision-avoidance algorithms implemented and evaluated in this study, outlining their theoretical foundations and operational principles as used in our field experiments.

2.1. COLREGS Overview

Although the COLREGs encompass a wide range of navigation-related provisions, the majority concern light and sound signals for ensuring navigational safety. The algorithms employed in this study concentrate on Rules 13–17, which present challenges from an autonomous-navigation perspective.

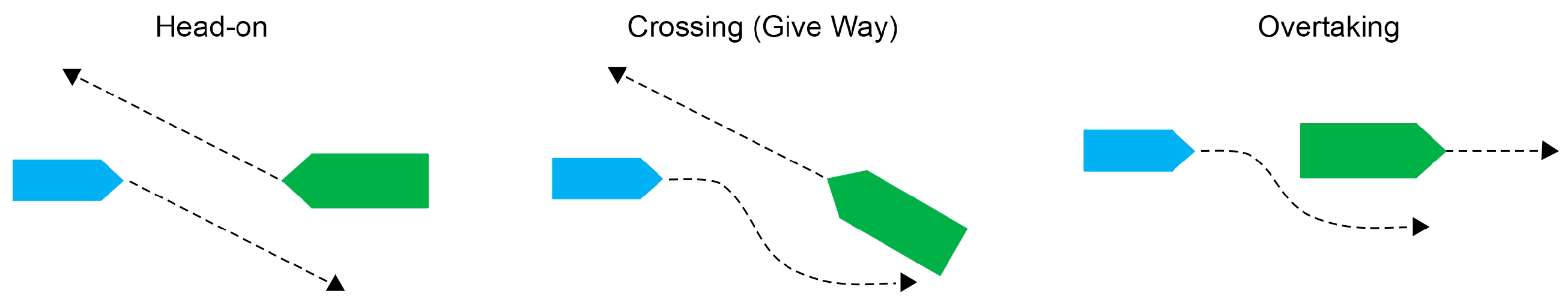

According to Rules 13–17 of the COLREGs, potential collision scenarios can be categorized into three types: head-on, crossing, and overtaking [

3].

Figure 1 presents an illustration of these maneuvers, where the blue vessel represents our USV and the green vessel represents the contact to be avoided. These maneuvers were selected in this study to enable a comparative assessment of the algorithms and to identify which one exhibits superior performance.

2.2. Behavior-Based Collision Avoidance

MOOS-IvP modular architectural framework was developed for the autonomous operation of maritime vehicles. A defining characteristic is its suite of

behaviors that drive real-time decision making. These behaviors are activated under specific environmental and mission conditions, allowing the system to react dynamically to hazardous situations and thus maintain navigational safety [

4].

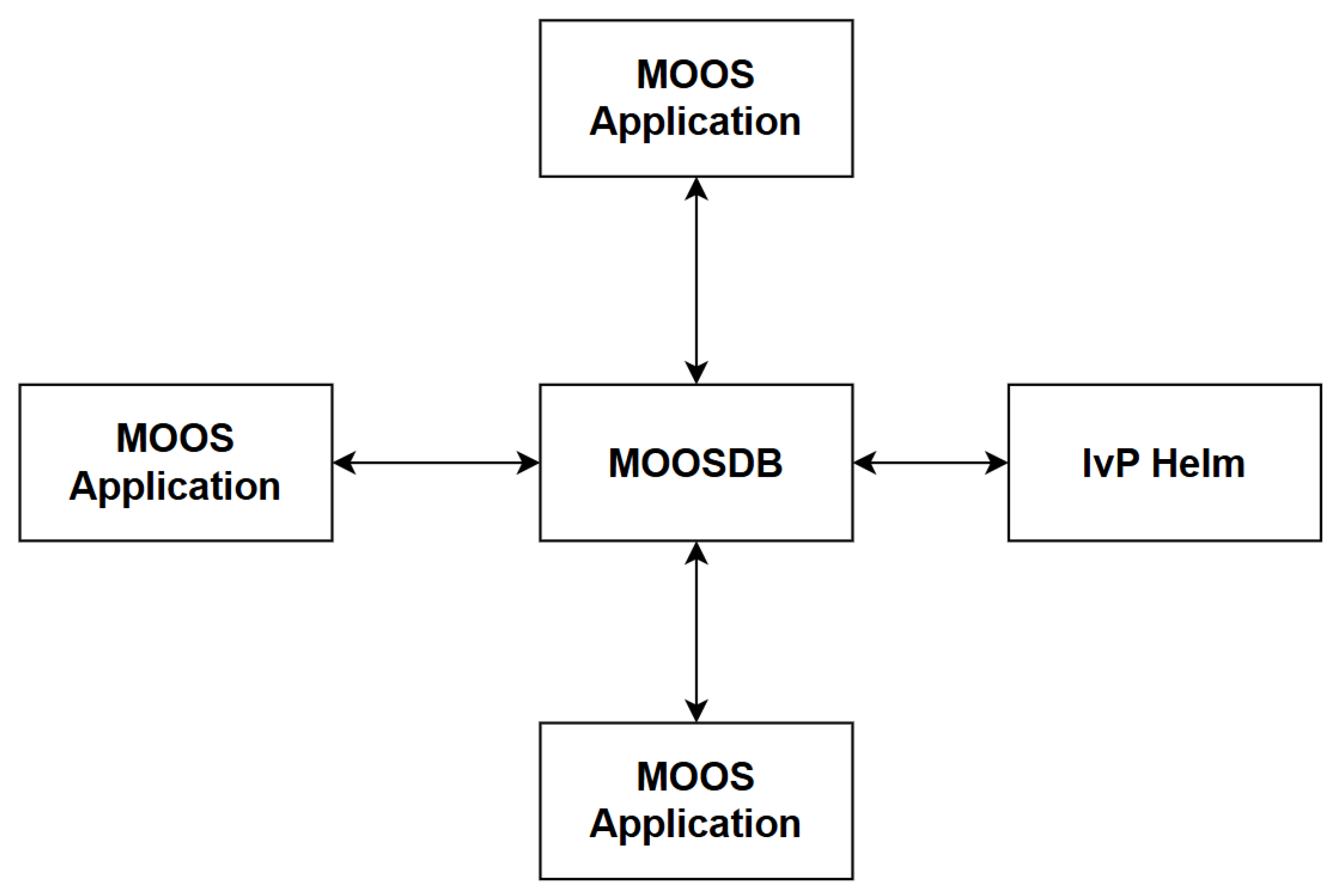

The system has a star topology, where the MOOS applications are connected to the MOOSDB, which acts as the central database that gathers all variables, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

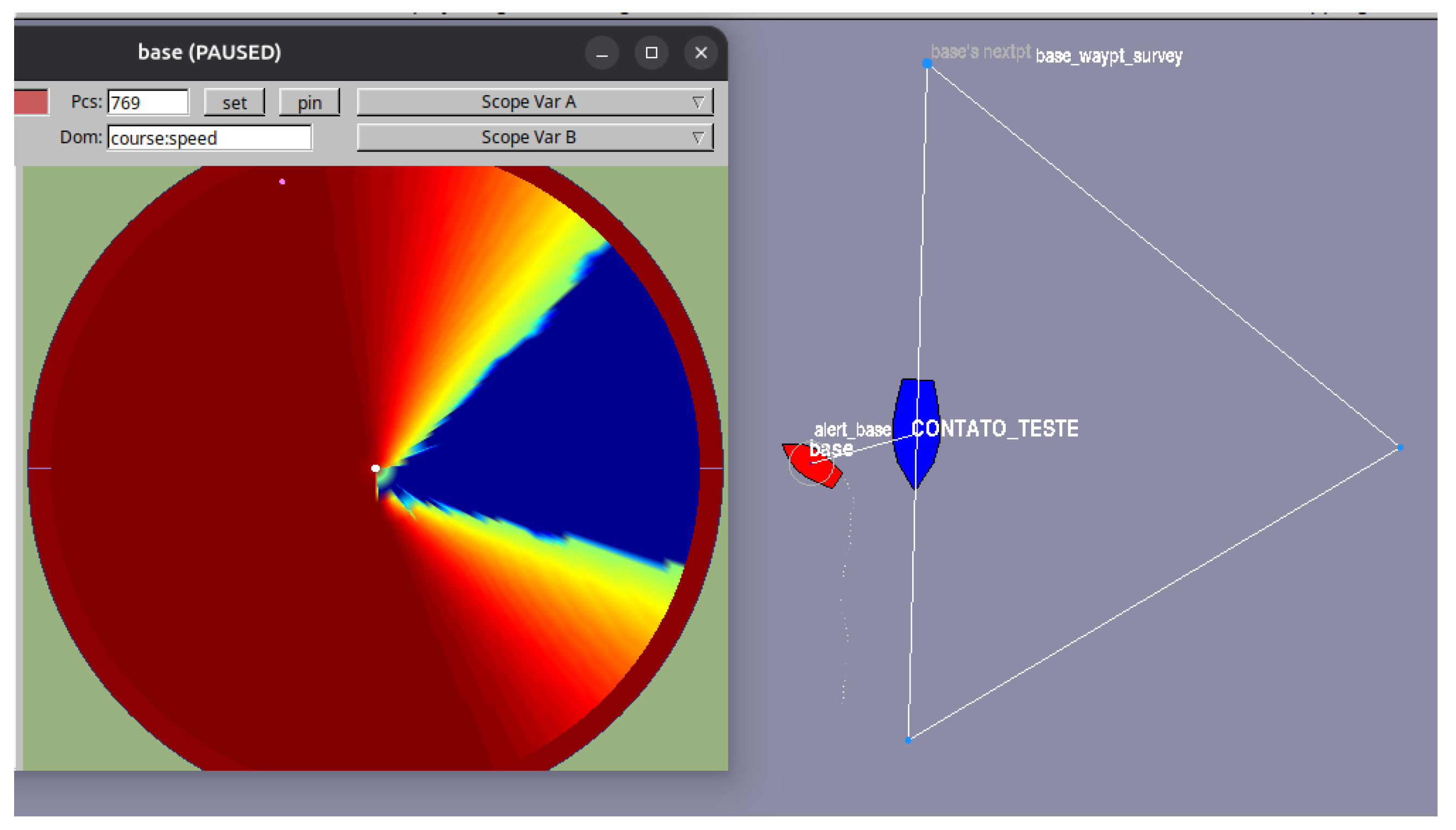

Each behavior generates an IvP function, which is subsequently sent to the IvP solver as we can see in

Figure 3. In this process, each function is assigned a specific weight, and the solver produces the final decision for the vehicle.

Among the core MOOS-IvP behaviors is the

Collision Avoidance behavior [

6], which is grounded in the CPA (Closest Point of Approach) concept. The CPA represents the minimum separation distance between two vessels, assuming both maintain their present speeds and headings. This metric is pivotal for predicting potential collisions and triggering timely corrective actions.

Figure 4 illustrates the MOOS-IvP collision avoidance behavior during operation. The right side presents a crossing scenario where the vessel designated as

base executes an avoidance maneuver to prevent collision with a contact identified as

CONTATO-TESTE. The blue region indicates zero Closest Point of Approach (CPA), while the red and yellow regions represent progressively larger CPA values. Consequently, the USV’s behavioral decision, as depicted in the figure, prioritizes contact avoidance by navigating toward regions with increased CPA values.

Some works that utilized MOOS-IvP for field tests include [

7,

8,

9]. In [

7], the COLREGs behavior was employed within the MOOS-IvP framework to perform collision avoidance maneuvers based on the AIS (Automatic Identification System) position of the contact during real tests conducted in a lake environment. In Alhattab et al. [

8], the MOOS-IvP framework was also utilized in field experiments for collision avoidance; however, in this case, the behavior was limited to obstacle avoidance without explicit compliance with the COLREGs. Similarly, MOOS-IvP was applied to avoid static obstacles in Benjamin et al. [

9], using a pre-existing behavior that was already available within the framework.

2.3. Velocity-Obstacle (VO) Algorithm

Originally proposed by Fiorini and Shiller for robot motion planning in dynamic environments [

10], the Velocity Obstacle (VO) method has become a popular real-time collision-avoidance approach.

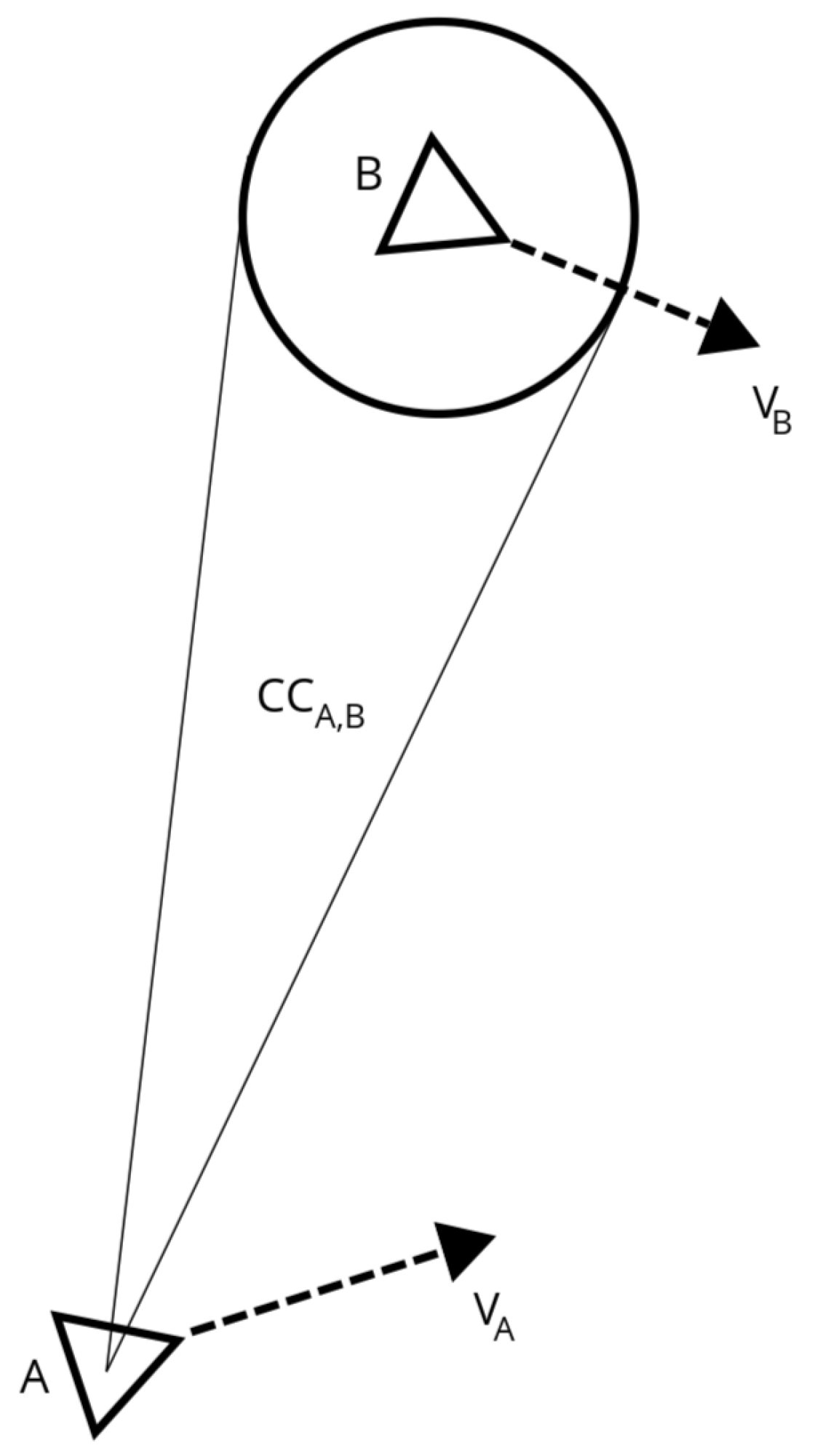

A VO represents the set of relative velocity vectors that would lead to a potential collision with an obstacle within a specified time horizon.

Figure 5 illustrates the conceptual representation of the VO approach, where

is the Collision Cone where any relative velocity that lies inside this cone would cause a collision between A and B. Once the own ship detects an obstacle, the collision avoidance logic requires it to execute a maneuver that shifts its velocity and course to a region outside the boundaries of the Collision Cone.

One early demonstration by Kuwata et al. [

11] integrated COLREGs (maritime right-of-way rules) into a VO-based collision avoidance system for USVs. This approach was validated both in simulation and through on-water trials, proving that VO could safely guide a USV in compliance with navigation rules. The VO algorithm in this system was able to execute rule-compliant maneuvers during close-quarters encounters.

In a different implementation, Zhuang et al. [

12] developed an embedded collision avoidance system that employed VO in conjunction with a marine radar sensor. The algorithm continuously adjusted the USV’s heading and speed in real time to avert collisions, using radar detections of dynamic obstacles. Multi-obstacle sea trials confirmed the effectiveness and reliability of this radar-based VO system, demonstrating safe navigation in a complex and cluttered maritime environment.

More recently, Cho et al. [

13] applied a modified VO algorithm, augmented with line-of-sight guidance and COLREGs compliance logic, on a full-scale experimental USV known as the M-Searcher. In extensive on-water experiments, the VO-based autopilot enabled the vessel to perform safe and COLREG-compliant evasive maneuvers under dynamic encounter conditions. The results showed that the system maintained proper rule-following behavior while avoiding collisions with both static and moving obstacles.

Each of these implementations underscores the practicality of VO methods for USV collision avoidance. By continuously recomputing safe velocities and incorporating maritime rules, VO-based systems have achieved real-time obstacle avoidance and rule-compliant navigation in live sea trials, marking an important step toward autonomous maritime operations.

2.4. A* Path Planning Algorithm

A* is a popular graph-search algorithm that has been widely applied to USV path planning for collision avoidance. It finds optimal paths on a grid-based map using heuristic cost evaluation and has been used in maritime navigation research since the 1990s [

14]. For example, Han et al. [

14] implemented an A*-based planner on the ARAGON USV to generate safe trajectories while respecting COLREGs. Their approach dynamically adjusted the search space based on collision risk and selected an optimal route that obeys COLREGs constraints. The ARAGON system was tested in real-world scenarios, including crossing and head-on encounters with multiple vessels, and successfully demonstrated autonomous collision avoidance in field trials.

Despite its efficiency, the standard A* algorithm produces piecewise-linear paths with abrupt turns and assumes static obstacles. To improve path feasibility for USVs, researchers have developed enhanced versions of A*. For instance, Song et al. [

15] proposed a

Smoothed A* variant that applies post-processing with multiple smoothers to eliminate sharp turns, yielding more continuous, navigable routes. Their refined A* algorithm, tested on the Springer USV platform, significantly reduced unnecessary deviations and outperformed the basic A* in both sparse and congested environments.

Another crucial improvement is incorporating dynamic obstacles and COLREGs into the planning. Traditional A* alone does not account for moving traffic or right-of-way rules, which are critical for maritime navigation [

16]. Recent studies address this issue by adding rule-based constraints and time-varying risk assessments to the A* search. For example, Singh et al. [

16] developed a constrained A* approach that enforces a safety buffer around the USV and factors in ocean currents and moving obstacle trajectories when generating waypoints. Such modifications enable the planner to remain effective in complex, changing environments.

In practice, A* is often integrated into a hybrid collision-avoidance framework to ensure real-time responsiveness and rule compliance. A common strategy is to use A* for global or mid-term path planning, then rely on a local avoidance algorithm for immediate collision prevention. For instance, Liang et al. [

17] combined a coarse global path from a “

-increment A*” with a local Dynamic Window Approach (DWA) that fine-tunes the trajectory in real time, explicitly incorporating COLREGs into decision-making. This layered approach leverages A*’s optimality for overall route planning while the local module handles dynamic avoidance maneuvers and compliance with maritime rules.

Overall, the A* algorithm (and its variants) has proven to be a viable foundation for USV collision avoidance and has seen successful real-world implementations in autonomous surface vessels.

3. Algorithm Suite Implemented on the USV

This section details the practical integration of each algorithm into the USV autonomy stack. All implementations run within MOOS-IvP, with behavior-level interfaces and consistent parameterization to enable fair comparisons under matched scenarios.

3.1. Geometric Classification of Collision Scenarios

For both the modified A* and the Velocity Obstacle (VO) algorithms, a set of mathematical formulations was employed to determine the geometric nature of potential collision situations. The approach follows the geometric reasoning proposed by [

18], which allows for classification of encounters based on the relative motion between vessels.

The relative course, or contact angle

, represents the angular difference between the target ship’s (TS) course

and the ownship’s (OS) course

, as illustrated in

Figure 6. It is defined as:

The relative bearing

corresponds to the difference between the bearing from the ownship to the target ship

and the ownship’s course

, expressed as:

These angular relationships enable the geometric classification of encounters—such as overtaking, crossing, and head-on situations—which are fundamental for determining the appropriate collision avoidance behavior according to the COLREGs.

In the implemented algorithm, these parameters are continuously computed during runtime from the navigation data of both the ownship and the contact vessel. The variable quantifies the relative orientation between both vessels’ headings, while provides the relative bearing of the target from the ownship’s perspective. By evaluating these angles, the system can infer the encounter type as follows:

Head-on: Detected when the relative bearing of the contact is approximately aligned with the ownship’s bow () and the relative course angle is nearly (). In this case, the system anticipates a reciprocal approach and enforces starboard maneuvers by blocking the starboard region in the A* grid map, steering the ownship to port in accordance with Rule 14 of the COLREGs.

Overtaking: Identified when the target vessel’s course is nearly aligned with the ownship’s (), indicating that the ownship is approaching from behind. The algorithm predicts the future position of the target by extrapolating its motion over a calculated interception time and plans a trajectory passing forward and to starboard, complying with Rule 13.

Crossing: Recognized when and fall within intermediate ranges (e.g., or ), indicating that the vessels’ paths will intersect. The algorithm prioritizes avoidance actions based on COLREGs Rules 15–17, typically yielding to a vessel approaching from starboard.

Once the encounter type is determined, the collision avoidance module dynamically adjusts the goal node of the A* path planner to guide the ownship toward a safe trajectory. For head-on situations, a fixed avoidance point is generated on the port side, and a starboard obstacle sector is inserted into the occupancy grid to enforce a safe deviation. In overtaking and crossing scenarios, the goal point is computed adaptively based on the predicted future position of the target vessel, enabling continuous recalculation of the path as the encounter evolves.

This integration of geometric classification with real-time path planning allows the system to combine deterministic COLREGs-compliant maneuver selection with optimal trajectory generation. As a result, the USV can autonomously resolve encounters by interpreting the spatial geometry of relative motion and adjusting its navigation decisions accordingly, achieving robust and compliant collision avoidance behavior at sea.

3.2. Behavior-Based Collision Avoidance

The implementation leverages the BHV_AvdColregsV22 behavior available in the MOOS-IvP distribution. This behavior calculates the Closest Point of Approach (CPA) for all detected contacts and evaluates potential collision risks based on geometric encounter classification. When a contact is deemed to pose a collision threat, the behavior activates and produces an objective function that modifies the vessel’s heading and speed to achieve safe separation.

The COLREGs behavior distinguishes between different encounter types—head-on, crossing, and overtaking—by analyzing the relative bearing

and relative course

of the contact vessel, as described in

Section 3.1. Based on this classification, the behavior enforces the appropriate right-of-way rule:

Head-on encounters (Rule 14): Both vessels alter course to starboard, passing port-to-port.

Crossing encounters (Rule 15): The give-way vessel (with the contact on its starboard side) alters course to pass astern of the stand-on vessel.

Overtaking encounters (Rule 13): The overtaking vessel maneuvers to pass clear of the vessel being overtaken, typically on the starboard side.

For this study, the behavior was configured with the following key parameters:

pwt_outer_dist = 50: Activation distance threshold (50 m) at which the behavior begins to influence the vehicle’s trajectory.

pwt_inner_dist = 30: Critical proximity distance (30 m) where maximum avoidance priority is assigned.

completed_dist = 1000: Distance (1000 m) at which the contact is considered safely passed and the behavior deactivates.

min_util_cpa_dist = 30: Minimum acceptable CPA distance (30 m) for trajectory selection.

max_util_cpa_dist = 50: CPA distance (50 m) beyond which no collision risk is perceived.

pwt_grade = linear: Linear interpolation of priority weight between outer and inner distance thresholds.

extrapolate = true: Enables extrapolation of contact trajectory when position updates are delayed.

decay = 30,60: Contact information decay parameters (30 s until start of decay, complete decay at 60 s).

Unlike the modified A* and VO algorithms, which were developed specifically for this study, the COLREGs behavior is a mature, field-tested component of the MOOS-IvP ecosystem. Its integration into the USV autonomy stack required minimal customization beyond parameter tuning, making it an efficient baseline for comparative evaluation. The behavior’s modular architecture allows it to coexist with other MOOS-IvP behaviors, such as waypoint following and station-keeping, enabling seamless transitions between mission phases.

3.3. Modified Velocity Obstacles (VO) Algorithm

The collision avoidance system implements a modified Velocity Obstacles (VO) algorithm adapted for maritime navigation and COLREGs compliance. This approach provides reactive collision avoidance by computing velocity-based collision cones in real-time.

The traditional VO algorithm addresses two main tasks: path planning and velocity planning. However, since the USV-M currently does not employ a velocity controller due to safety constraints during the development stage, only the path-planning component of the algorithm was utilized in this study.

Consequently, the primary difference between the original VO method described in

Section 2.3 and the approach implemented here lies in the integration of COLREGs-based decision rules to guide the maneuver once the obstacle’s Collision Cone has been identified.

The core collision avoidance logic executes at each iteration cycle, performing the following operations:

The modified VO algorithm follows the execution flow illustrated in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Modified Velocity Obstacles Collision Avoidance |

- 1:

Input: Ownship state , Contact list - 2:

Output: Avoidance heading , Avoidance speed - 3:

- 4:

if

then - 5:

, - 6:

return - 7:

end if - 8:

- 9:

for each contact do - 10:

Calculate relative bearing - 11:

Calculate distance - 12:

Determine COLREGs situation (Head-on, Crossing, Overtaking) - 13:

if and situation requires avoidance then - 14:

Compute collision cone angle - 15:

Calculate cone boundaries - 16:

Apply COLREGS rules - 17:

Goes to Desired Heading - 18:

end if - 19:

end for - 20:

- 21:

Normalize to - 22:

return ,

|

3.4. Modified A* Path-Planning Algorithm

This study proposes a modified A* search algorithm as one of the approaches for maritime collision-avoidance scenarios within the MOOS-IvP framework. The core difference from the conventional A* algorithm is the incorporation of the COLREGs decision logic described in

Section 2.1. As a result, the generated trajectory is no longer solely the shortest path but instead respects the navigational constraints imposed by the applicable maritime rules.

A two-dimensional grid of

nodes was generated to represent the operational area as we can see in

Figure 7. Each node stores its Cartesian position

, obstacle and visitation flags, and connections to its four adjacent neighbors (north, south, east, and west). Prior to each search, all nodes are reinitialized with infinite costs and unvisited status. The heuristic and distance functions are Euclidean, and the start node is initialized with zero local cost and a global cost equal to the heuristic distance to the goal.

The fundamental cost definitions follow the standard A* formulation:

| Symbol | Meaning | Computation |

| g | Local cost () | Cumulative distance from start to current node |

| h | Heuristic | Direct Euclidean distance to goal node |

| f | Global cost () | |

At each iteration, the node with the smallest f value is expanded first.

To tailor the algorithm to maritime navigation, several modifications were introduced:

Start and Goal Selection: The start node corresponds to the USV’s current position, while the goal node depends on the encounter geometry. In head-on situations, the goal is positioned diametrically opposite to the vessel’s heading.

Obstacle Modeling: Each contact ship is modeled as a circular obstacle, with its radius representing a safety distance around the target. The grid cells intersecting this region are marked as occupied.

Dynamic Updates: The A* path is continuously updated while the contact remains forward of the USV beam. Once the target passes abeam, dynamic updates are halted and the nominal route is resumed.

Safety Correction: In cases where the USV’s initial position lies within an obstacle zone (e.g., due to close contact proximity), the algorithm selects the nearest free node as the effective start position.

Overtaking Rule Adaptation: During overtaking maneuvers, an additional constraint is imposed to favor trajectories passing astern of the target, preventing bow crossings in compliance with COLREGs Rule 13.

For each encounter type (head-on, crossing, overtaking), a region of the grid corresponding to the target’s restricted sector is treated as an obstacle zone. For example, in head-on encounters, the starboard sector extending from the contact’s bearing to the edge of the grid is masked as a forbidden region, enforcing the prescribed maneuver to starboard.

The Algorithm 2 begins with an input consisting of the USV’s own state, specifically its position and velocity, along with a list of nearby contacts in proximity to the USV. If no contacts are present, the algorithm is not executed. When contacts are detected, the algorithm determines the collision type for each contact and subsequently calculates a desired heading for the USV to follow. In the current implementation, the USV’s velocity remains unmodified due to the absence of a velocity controller at this stage of development.

| Algorithm 2: COLREGs-Aware A* Path Planning |

- Require:

Grid map with obstacle zones, start node S, goal node G - Ensure:

Safe path from S to G avoiding forbidden sectors - 1:

Initialize all nodes: , visited ← false - 2:

, Euclidean(S,G), - 3:

Push S into OpenList (priority queue ordered by f) - 4:

while OpenList not empty do - 5:

node with lowest f from OpenList - 6:

if then break - 7:

for each neighbor m of n do - 8:

if m is obstacle or forbidden (COLREGs zone) then continue - 9:

Euclidean(n,m) - 10:

if then - 11:

- 12:

Euclidean(m,G) - 13:

- 14:

parent - 15:

Push m into OpenList - 16:

end if - 17:

end if - 18:

end for - 19:

end if - 20:

end while - 21:

return reconstructed path from G to S

|

As explained in

Section 2.2, MOOS-IvP, one of the frameworks used in the USV-M, enables the use of multiple behaviors during runtime. After computing the path to be followed by the USV using the Modified A* algorithm, the calculated points are sent to the MOOS-IvP Waypoint Behavior [

19], which receives a route of waypoints for the USV to follow. Since the framework allows multiple behaviors to run simultaneously, the behavior priority was adjusted according to the distance from the target to be avoided. When the target is within a certain range, the behavior containing the modified A* algorithm points is activated, and the USV follows the path determined by those waypoints.

4. Materials and Methods for Field Validation

4.1. Hardware System

The USV-M (Unmanned Surface Vehicle Multipurpose) (

Figure 8) is being developed by the Naval Systems Analysis Center (CASNAV) through a project funded by FINEP in partnership with DGS Defense. The platform features advanced technical specifications and can be equipped with a wide range of payloads, including side-scan and multibeam sonars, infrared-spectrum surveillance cameras, ruggedized onboard computers, satellite gyroscopes, and inertial measurement units (IMUs). The sensor suite is customized on a case-by-case basis, with each mission defining its own optimal configuration of hardware and instrumentation. Therefore, this USV is restricted to near-shore operations and is not intended for open water missions. The principal dimensions of the USV are presented in

Table 1.

The vehicle supports three operational modes: tele-operated, semi-autonomous, and fully autonomous. In the experimental campaign described later in this paper, the USV-M was operated in autonomous mode to evaluate its capability to detect the presence of nearby vessels and dynamically adjust its trajectory to prevent potential collisions.

The USV-M represents an evolution of the USV-Lab, whose autonomous control architecture was previously implemented and validated in [

20].

4.2. Software System

As we can see in

Figure 9 in the center of the USV software system there is a ROS2 implemented proprietary code that communicates with MOOS-IvP through a TCP Bridge, with this framework being responsible for carrying out the path planning task for the USV.

All algorithms were implemented within the MOOS-IvP autonomy stack. The community follows the standard star topology, with a central MOOSDB hosting inter-application variables, while behaviors and applications publish/subscribe to execute perception and decision-making in real time. The IvP Helm aggregates behavior objective functions and solves a multi-objective problem, issuing the final helm command.

Three MOOS-IvP applications were developed for this study and are available open-source in our repository:

pContactSpawn: spawns virtual contacts for controlled encounter geometries (head-on, crossing, overtaking). Contacts are generated with user-defined kinematics to exercise COLREGs-compliant responses.

pAstarColAvd: performs collision avoidance using an A*-based algorithm with COLREGs-aware forbidden sectors and dynamic re-planning.

pColAvdvo: performs collision avoidance using a modified VO algorithm with COLREGs-aware forbidden sectors and dynamic re-planning.

Three mission bundles are provided to reproduce the experiments with matched scenarios and metrics:

col_avd_moos (IvP COLREGs behavior),

astar (modified A*), and

velocity_obstacle (VO) (see repository

1). The repository’s README documents the modules and the exact contact-spawn interface, which we used verbatim in sea trials.

4.3. Algorithm Parameters and Configuration

To ensure reproducibility and enable comparative analysis, all algorithms were configured with consistent safety parameters where applicable.

Table 2 summarizes the key parameters used in each collision avoidance approach.

Parameter Selection Rationale

The parameters in

Table 2 were selected based on the following considerations:

Safety distances (25–50 m): The safety radius and activation distances were chosen based on the USV-M’s operational characteristics: a 4.5 m vessel length with maximum speed of 30 knots. The 25 m safety radius provides approximately 5 vessel lengths of clearance, consistent with maritime safety practices. The 50 m activation distance allows sufficient time for maneuver computation and execution at typical operating speeds.

CPA thresholds (25–50 m): The minimum acceptable CPA of 30 m ensures safe passage while avoiding excessive detours. The maximum CPA threshold of 50 m defines the boundary beyond which collision risk is negligible, preventing unnecessary avoidance maneuvers in open water scenarios.

Grid resolution (1 m/node): The A* grid resolution balances computational efficiency with path precision. At 1 m spacing, the grid provides sufficient granularity for a 4.5 m vessel while maintaining reasonable memory requirements.

Update frequency (1 Hz): The 1 Hz update rate for both VO and A* algorithms ensures responsive collision avoidance while limiting computational load.

4.4. Experimental Design

To enhance the safety level of the experiments and eliminate the risk of physical collisions, all vessels were represented as simulated contacts.

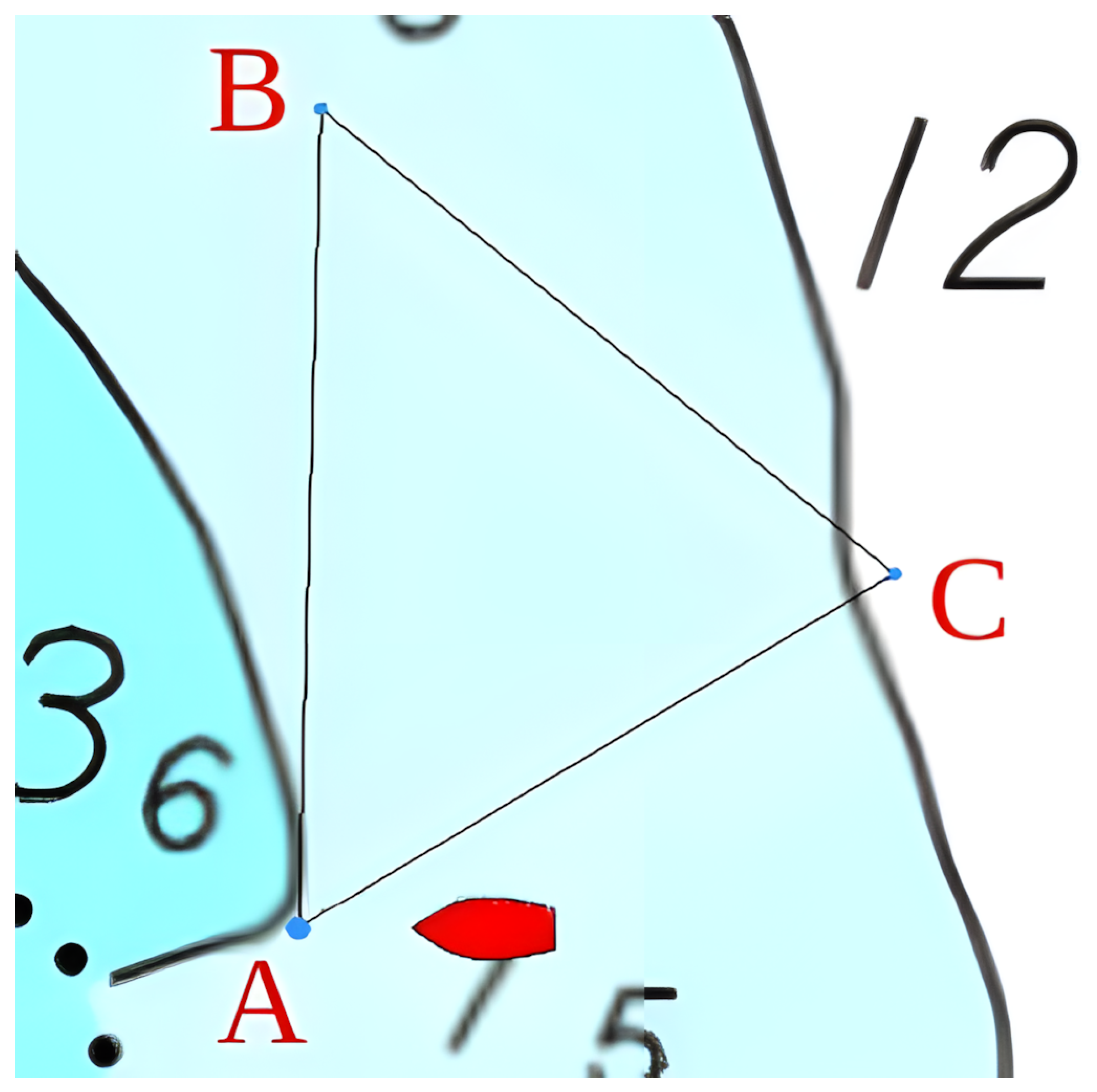

Virtual contacts appeared each time the USV reached one of the triangle vertices, positioned as shown in

Figure 10 and

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Figure 11 illustrates the three virtual contact scenarios used in the experiments, which simulate three distinct collision avoidance situations prescribed by the COLREGs at each virtual contact encounter. Specifically, the virtual contacts represented: (i) a head-on encounter (

Figure 11a), in which the contact approaches and the USV is required to execute a starboard turn to avoid collision; (ii) an overtaking encounter (

Figure 11c), in which the USV would collide with the stern of a stationary virtual contact if it continued toward the waypoint; and (iii) a crossing encounter (

Figure 11b), in which the contact crosses the USV bow, requiring an evasive maneuver. These maneuvers are described in

Section 2. The position, speed, and course parameters of each virtual contact for all encounter situations are detailed in

Table 3.

4.5. Data Analysis

In this study, we adopt a set of indicators inspired by the metrics proposed in Yu and Roh [

21], enabling a direct comparison between different collision-avoidance algorithms. These metrics include:

CPA (m)—Closest Point of Approach:

Indicates the minimum distance between the vessels’ projected paths, and is fundamental for assessing the severity of a potential encounter. A larger CPA value indicates safer navigation, as it represents greater separation between vessels. Conversely, smaller CPA values indicate higher collision risk.

Distance traveled (m):

Evaluates the total path length, allowing for the assessment of whether collision-avoidance maneuvers significantly increase the voyage distance.

Percentage change in distance traveled (%):

Quantifies how much the final route length differs from the original in relative terms.

Time (s):

Amount of time between waypoints during sea trials.

5. Field Validation

The experimental sea trials were conducted in Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), near the Brazilian Naval Academy (Escola Naval), as show in

Figure 12In the conducted tests the contacts for avoidance were placed virtually. However, this area presents excellent opportunities for future studies on avoidance algorithms due to the heavy vessel traffic, as verified in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. This condition also required reducing the USV speed during the tests.

For better visualization, the nautical chart background was removed from the triangular trajectory plots in

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, which subfigures (a) and (b) depict the head-on scenario, subfigures (c) and (d) illustrate the overtaking scenario, and subfigures (e) and (f) demonstrate the crossing situation.

Figure 17 presents the complete paths executed by each algorithm.

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 summarize the performance of the COLREGs Behavior, modified Velocity Obstacle, and modified A* algorithms across the three legs of the triangular trajectory.

6. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate distinct performance characteristics among the evaluated collision avoidance algorithms. The Closest Point of Approach (CPA) analysis revealed that both the COLREGs behavior (30.0 m average) and the Modified A* algorithm (30.0 m average) achieved safer separation distances compared to the Velocity Obstacle algorithm (13.0 m average). While the VO algorithm maintained trajectories closer to the obstacles, potentially increasing collision risk, it should be noted that all algorithms maintained CPA values above critical safety thresholds for the USV’s operational parameters.

Regarding trajectory efficiency metrics, the COLREGs behavior consistently outperformed alternative approaches across multiple parameters. Specifically, this behavior achieved the shortest total distance traveled, the minimum mission completion time, and the smallest distance increment relative to the optimal path.

In terms of overall performance assessment, the COLREGs behavior implementation within the MOOS-IvP framework demonstrated superior performance compared to other algorithms evaluated in this study. This superiority was evidenced through reduced total distance traveled, decreased mission execution time, and minimal path deviation from the original trajectory. These findings suggest that the COLREGs behavior approach provides an effective balance between regulatory compliance and navigational efficiency in autonomous surface vehicle operations.

Several limitations of this work should be acknowledged. First, due to operational constraints each collision avoidance algorithm was evaluated through a single experimental run. Second, all collision scenarios were based on virtual contacts rather than real vessels, which simplified the experimental setup but may not fully capture the complexity of real-world encounters. Third, the trials were conducted in a specific geographic location with particular environmental conditions, which may affect the generalizability of the results.

Regarding the algorithms themselves, each approach has inherent limitations that should be considered. The Modified A* algorithm depends on a fixed local grid and is computationally intensive for large areas, this was mitigated in our study by using a limited operational area. Additionally, this implementation only handles single contact scenarios. The Modified VO algorithm, in its current implementation, also addresses only one contact at a time. In contrast, the Behavior-Based Collision Avoidance algorithm demonstrates the capability to handle multiple contacts simultaneously, which represents an advantage for more complex encounter scenarios.

Future work should address these limitations through replicated trials under varying environmental conditions, with real-vessel encounters using onboard sensor data acquisition, and by extending the single-contact algorithms to handle multiple simultaneous collision avoidance scenarios.

7. Conclusions

This study implemented and compared three collision avoidance algorithms for USVs. Through sea trials, quantitative results were obtained to evaluate the performance of each algorithm and to identify the optimal solution for the USV platform under investigation. The experimental results demonstrated that the COLREGs behavior algorithm, which is natively implemented in the MOOS-IvP architecture, exhibited superior performance compared to the other tested algorithms across all evaluated metrics.

The experimental results demonstrated that the COLREGs behavior algorithm exhibited the best balance between safety and efficiency. While the VO algorithm achieved closer passages to obstacles (13.0 m average CPA), this represents a higher risk profile rather than superior performance. The COLREGs behavior maintained adequate safety margins (30.0 m average CPA) while achieving the shortest total distance (179.4 m), minimum completion time (174.7 s), and smallest route deviation (27.2% increase), demonstrating that safety and efficiency are not mutually exclusive when properly implemented.

These findings represent a significant contribution to the advancement of obstacle avoidance technology for autonomous maritime systems. The comparative analysis provides valuable insights for the selection and implementation of collision avoidance strategies in USV applications, particularly in scenarios requiring compliance with international maritime regulations while maintaining operational efficiency. The validation through real-world sea trials enhances the reliability and applicability of these results for future autonomous navigation system development.

8. Future Work

Future research will focus on enhancing the collision avoidance algorithm through the integration of multi-sensor fusion techniques for the autonomous detection of multiple contacts and obstacles in various environmental conditions. The proposed approach will incorporate radar, camera and AIS systems to enable real-time obstacle identification and avoidance maneuvers. This sensor fusion strategy aims to provide robust environmental perception capabilities, allowing the USV to autonomously detect and classify maritime obstacles without human intervention. The implementation of this integrated perception system will further advance the autonomy level of unmanned surface vehicles, contributing to safer and more efficient maritime operations in complex navigational scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.d.L., G.A.B. and E.A.T.; methodology, D.S.d.L., G.A.B. and E.A.T.; software, D.S.d.L.; validation, D.S.d.L.; formal analysis, D.S.d.L.; investigation, D.S.d.L.; resources, D.S.d.L.; data curation, D.S.d.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.d.L.; writing—review and editing, D.S.d.L., G.A.B. and E.A.T.; visualization, D.S.d.L.; supervision, G.A.B. and E.A.T.; project administration, G.A.B. and E.A.T.; funding acquisition, E.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by FINEP, CASNAV (Naval Systems Analysis Center), by the CNPq – Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (process #300884/2025-7) and TPN-USP Ship Maneuvering Simulation Center.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

To the Brazilian Navy, TPN-USP, CASNAV and the entire VSNT project crew for all the support and for making resources available for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marinha do Brasil, Diretoria de Portos e Costas. Normas da Autoridade Marítima para Embarcações Autônomas—NORMAM-205/DPC; Portaria DPC/DGN/MB nº 177, de 27 de Março de 2025; Documento oficial da Autoridade Marítima Brasileira; Autoridade Marítima Brasileira: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization. International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs); As Amended; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, H.; Hao, Z.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Sun, X.; Zhang, G.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. Ship Autonomous Collision-Avoidance Strategies—A Comprehensive Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M.R.; Schmidt, H.; Newman, P.M.; Leonard, J.J. Nested autonomy for unmanned marine vehicles with MOOS-IvP. J. Field Robot. 2010, 27, 834–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M. IvP Helm Autonomy, n.d. Available online: https://oceanai.mit.edu/ivpman/pmwiki/pmwiki.php?n=Helm.HelmAutonomy (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- MIT, O. Behavior: AvoidCollision. Available online: https://oceanai.mit.edu/ivpman/pmwiki/pmwiki.php?n=BHV.AvoidCollision (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Cole, B.; Benjamin, M.R.; Randeni, S. AIS-Based Collision Avoidance in MOOS-IvP using a Geodetic Unscented Kalman Filter. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2021: San Diego–Porto, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–23 September 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhattab, Y.A.; Abidin, Z.B.Z.; Faizabadi, A.R.; Zaki, H.F.M.; Ibrahim, A.I. Integration of Stereo Vision and MOOS-IvP for Enhanced Obstacle Detection and Navigation in Unmanned Surface Vehicles. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 128932–128956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M.R.; Defilippo, M.; Robinette, P.; Novitzky, M. Obstacle Avoidance Using Multiobjective Optimization and a Dynamic Obstacle Manager. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 44, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, P.; Shiller, Z. Motion planning in dynamic environments using velocity obstacles. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1998, 17, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, Y.; Wolf, M.T.; Zarzhitsky, D.; Huntsberger, T. Safe maritime autonomous navigation with COLREGs, using velocity obstacles. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 4728–4734. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Z.; Gong, J.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, J. Radar-based embedded system for collision avoidance of USVs using VO method. Ocean. Eng. 2016, 127, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Park, B. Autonomous navigation system for unmanned surface vehicles using COLREGs-based fuzzy reasoning and velocity obstacle method. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 180, 212–229. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Campbell, S.; Naeem, W.; Xu, T.; Sutton, R. COLREGS-compliant collision avoidance using velocity obstacles and A* search. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 1300–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Smoothing A*-based path planning for unmanned surface vehicles in marine environments. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2019, 82, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Patel, A.; Verma, N. Constrained A* path planning for USVs in dynamic maritime environments with COLREGs compliance. In Proceedings of the IEEE OCEANS Conference, Gulf Coast, MI, USA, 25–28 September 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, M. Hybrid global-local collision avoidance for USVs: Integrating angle-based A* and DWA with COLREGs logic. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 280, 116123. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, J.; Dunbabin, M.; Ford, J.J. COLREG Scenario classification and Compliance Evaluation with temporal and multi-vessel awareness for collision avoidance systems. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 313, 119552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT Ocean Engineering. BHV_Waypoint—MOOS-IvP Autonomy Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://oceanai.mit.edu/ivpman/pmwiki/pmwiki.php?n=BHV.Waypoint (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- De Lima, D.S.; de Oliveira Carvalho, P.A.; de Carvalho, E.E.; Tannuri, E.A.; de Moraes, C.C.; Breitinger, A.R. Towards Autonomous Control System in Brazilian Navy’s USV-Lab using MOOS-IvP framework. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Roh, M.I. Method for anti-collision path planning using velocity obstacle and A* algorithms for maritime autonomous surface ship. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 16, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Illustrative diagram of the COLREGs rules used in this work.

Figure 1.

Illustrative diagram of the COLREGs rules used in this work.

Figure 2.

MOOS Community.

Figure 2.

MOOS Community.

Figure 3.

IvP Helm Architecture. Source: Adapted from [

5].

Figure 3.

IvP Helm Architecture. Source: Adapted from [

5].

Figure 4.

Collision Avoidance Behavior in MOOS-IvP.

Figure 4.

Collision Avoidance Behavior in MOOS-IvP.

Figure 5.

Velocity Obstacle Representation.

Figure 5.

Velocity Obstacle Representation.

Figure 6.

Geometric Representation of Ownship and Target Ship. Source: Adapted from [

18].

Figure 6.

Geometric Representation of Ownship and Target Ship. Source: Adapted from [

18].

Figure 7.

Region of the modified A* grid in the Nautical Chart.

Figure 7.

Region of the modified A* grid in the Nautical Chart.

Figure 8.

Unmanned Surface Vessel Multipurpose.

Figure 8.

Unmanned Surface Vessel Multipurpose.

Figure 9.

Software System Overview.

Figure 9.

Software System Overview.

Figure 10.

Triangle trajectory proposed to the tests.

Figure 10.

Triangle trajectory proposed to the tests.

Figure 11.

Path comparison for different virtual contact scenarios.

Figure 11.

Path comparison for different virtual contact scenarios.

Figure 12.

USV-M during Sea Tests in Guanabara Bay.

Figure 12.

USV-M during Sea Tests in Guanabara Bay.

Figure 13.

Vessels Traffic during Sea Tests with USV-M in Guanabara Bay.

Figure 13.

Vessels Traffic during Sea Tests with USV-M in Guanabara Bay.

Figure 14.

Collision Avoidance Maneuvers using COLREGs Behavior—Top row: Head-on collision avoidance; Middle row: Overtaking collision avoidance; Bottom row: Crossing collision avoidance.

Figure 14.

Collision Avoidance Maneuvers using COLREGs Behavior—Top row: Head-on collision avoidance; Middle row: Overtaking collision avoidance; Bottom row: Crossing collision avoidance.

Figure 15.

Collision Avoidance Maneuvers using the modified velocity obstacle algorithm—Top row: Head-on avoidance; Middle row: Overtaking collision avoidance; Bottom row: Crossing collision avoidance; The red lines represent the Collision Cone in real-time execution.

Figure 15.

Collision Avoidance Maneuvers using the modified velocity obstacle algorithm—Top row: Head-on avoidance; Middle row: Overtaking collision avoidance; Bottom row: Crossing collision avoidance; The red lines represent the Collision Cone in real-time execution.

Figure 16.

Collision Avoidance Maneuvers using the modified A* algorithm—Top row: Head-on collision avoidance; Middle row: Overtaking collision avoidance; Bottom row: Crossing collision avoidance.

Figure 16.

Collision Avoidance Maneuvers using the modified A* algorithm—Top row: Head-on collision avoidance; Middle row: Overtaking collision avoidance; Bottom row: Crossing collision avoidance.

Figure 17.

Complete USV trajectories using different collision avoidance methods.

Figure 17.

Complete USV trajectories using different collision avoidance methods.

Table 1.

Principal Dimensions of the USV.

Table 1.

Principal Dimensions of the USV.

| Specifications | USV-M |

|---|

| Length | m |

| Breadth | 2 m |

| Draft | m |

| Displacement | t |

| Payload | 500 kg |

| Max Speed | 30 knots |

| Propulsion | 1 × 90 hp motor |

Table 2.

Algorithm configuration parameters for field trials.

Table 2.

Algorithm configuration parameters for field trials.

| Algorithm | Parameter | Value |

|---|

| COLREGs Behavior | Activation distance (pwt_outer_dist) | 50 m |

| | Critical proximity (pwt_inner_dist) | 25 m |

| | Completion distance (completed_dist) | 1000 m |

| | Minimum acceptable CPA (min_util_cpa_dist) | 30 m |

| | Maximum CPA threshold (max_util_cpa_dist) | 50 m |

| | Priority weight function (pwt_grade) | linear |

| | Contact extrapolation (extrapolate) | true |

| | Contact decay parameters (decay) | 30, 60 s |

| Modified VO | Safety radius () | 25 m |

| | Collision detection threshold () | 50 m |

| | Update frequency | 1 Hz |

| Modified A* | Grid dimensions | 1023 × 938 nodes |

| | Grid resolution | 1 m/node |

| | Obstacle safety radius | 25 m |

| | Heuristic function | Euclidean distance |

| | Path update frequency | 1 Hz |

Table 3.

Virtual contact configuration for collision avoidance scenarios.

Table 3.

Virtual contact configuration for collision avoidance scenarios.

| Parameter | Head-On | Overtaking | Crossing |

|---|

| Distance from USV | 142 m | 63 m | 161 m |

| Speed | 2 knots | 0 knots | 4 knots |

| Course | 182° | 130° | 16° |

Table 4.

Triangle waypoints.

Table 4.

Triangle waypoints.

| Waypoint | Latitude (deg) | Longitude (deg) |

|---|

| A | | |

| B | | |

| C | | |

Table 5.

COLREGs Behavior algorithm performance metrics.

Table 5.

COLREGs Behavior algorithm performance metrics.

| Leg | CPA (m) | Distance (m) | Time (s) | Distance Increase (%) |

|---|

| First (A→B) | 23 | 203.5 | 163 | 31.4 |

| Second (B→C) | 42 | 197.4 | 226 | 43.4 |

| Third (C→A) | 25 | 137.3 | 135 | 6.7 |

| Mean | 30.0 | 179.4 | 174.7 | 27.2 |

Table 6.

Velocity Obstacle algorithm performance metrics.

Table 6.

Velocity Obstacle algorithm performance metrics.

| Leg | CPA (m) | Distance (m) | Time (s) | Distance Increase (%) |

|---|

| First (A→B) | 4 | 193.3 | 165 | 24.8 |

| Second (B→C) | 21 | 239.0 | 258 | 73.6 |

| Third (C→A) | 14 | 147.2 | 135 | 14.4 |

| Mean | 13.0 | 193.1 | 186.0 | 37.6 |

Table 7.

A* algorithm performance metrics.

Table 7.

A* algorithm performance metrics.

| Leg | CPA (m) | Distance (m) | Time (s) | Distance Increase (%) |

|---|

| First (A→B) | 22 | 188.5 | 156 | 21.8 |

| Second (B→C) | 39 | 202.8 | 234 | 47.4 |

| Third (C→A) | 29 | 219.2 | 217 | 70.4 |

| Mean | 30.0 | 203.5 | 202.3 | 46.5 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).