Pore Structure Evolution in Marine Sands Under Laterally Constrained Axial Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Experimental Apparatus and Materials

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Image Processing and Phase Segmentation

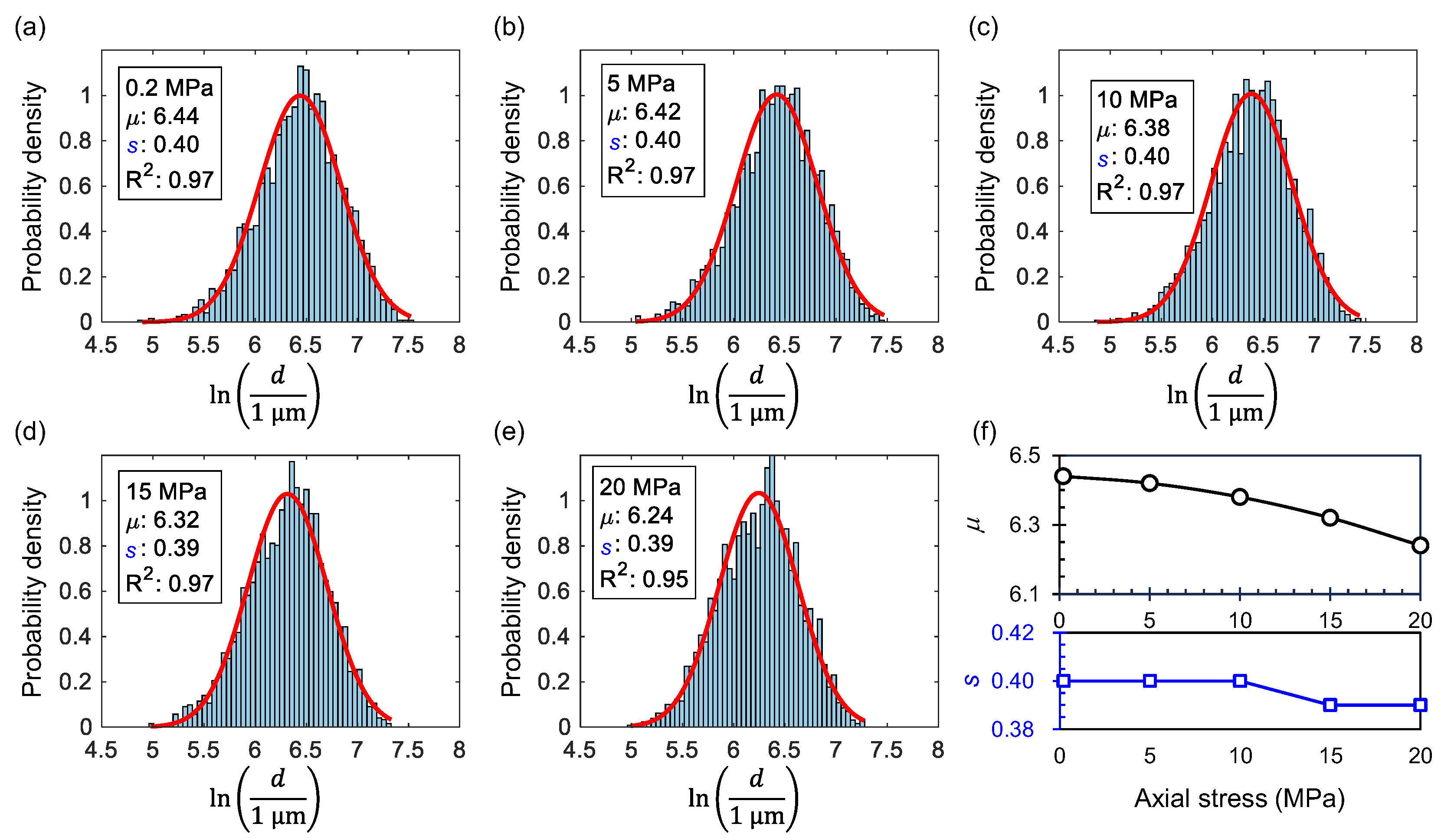

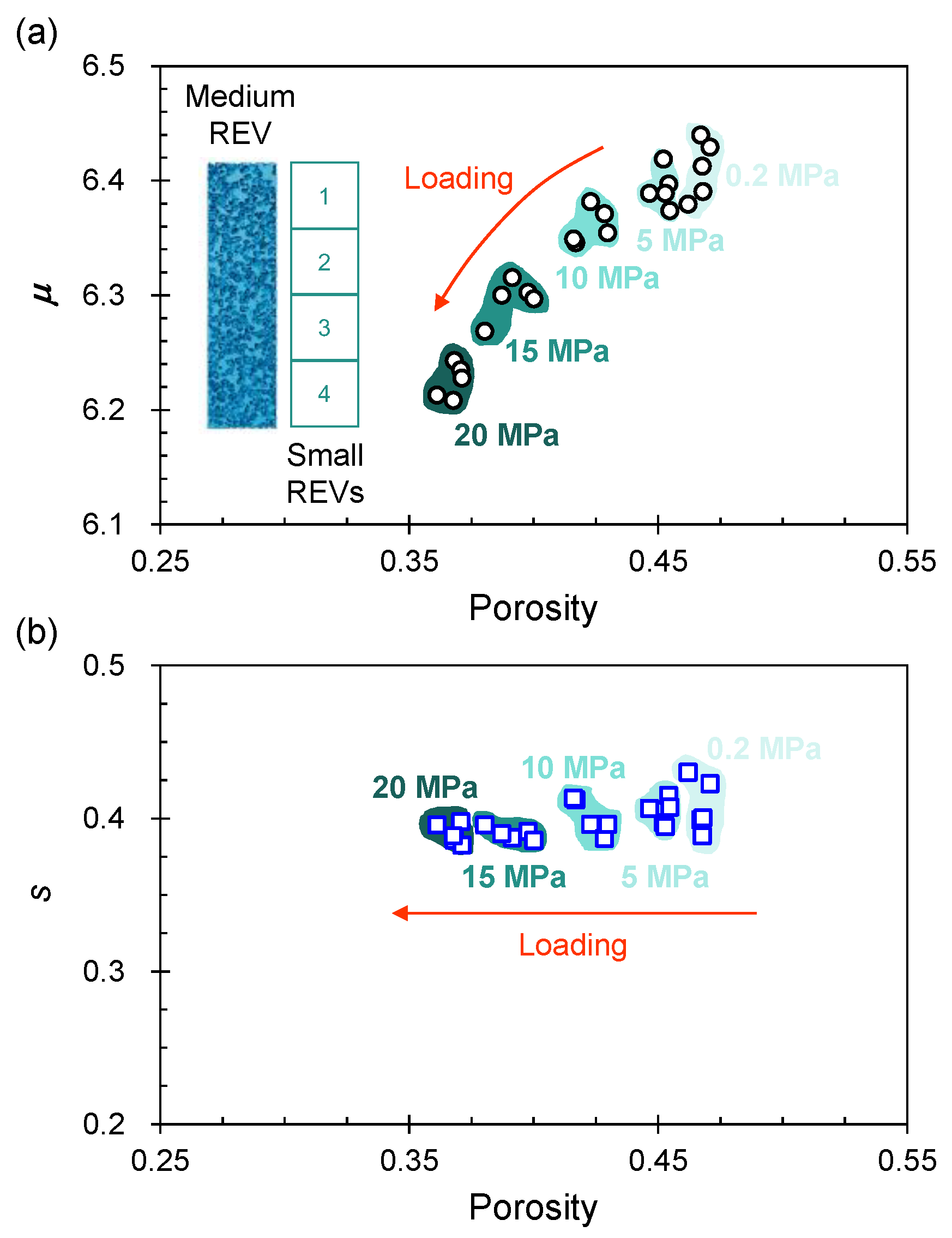

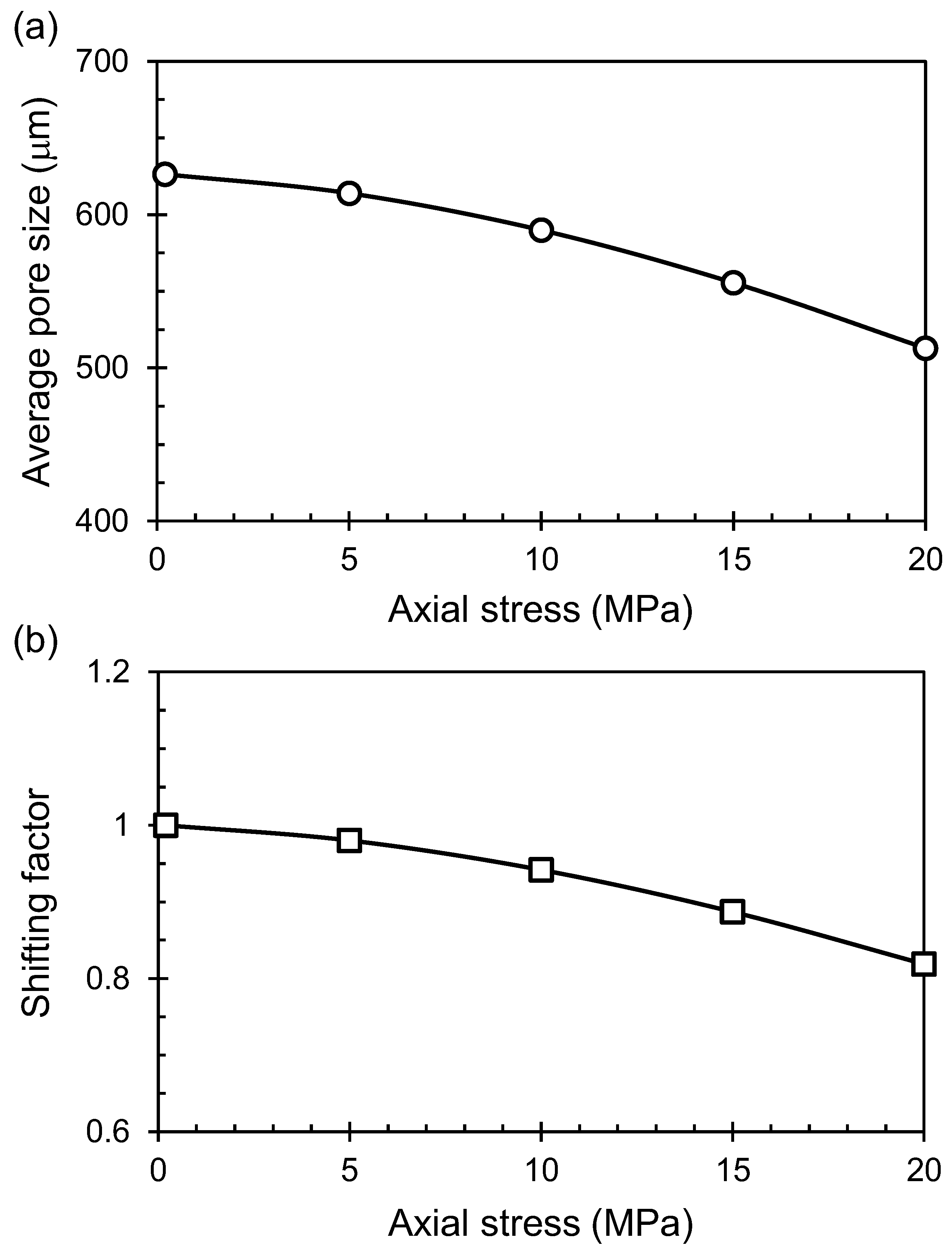

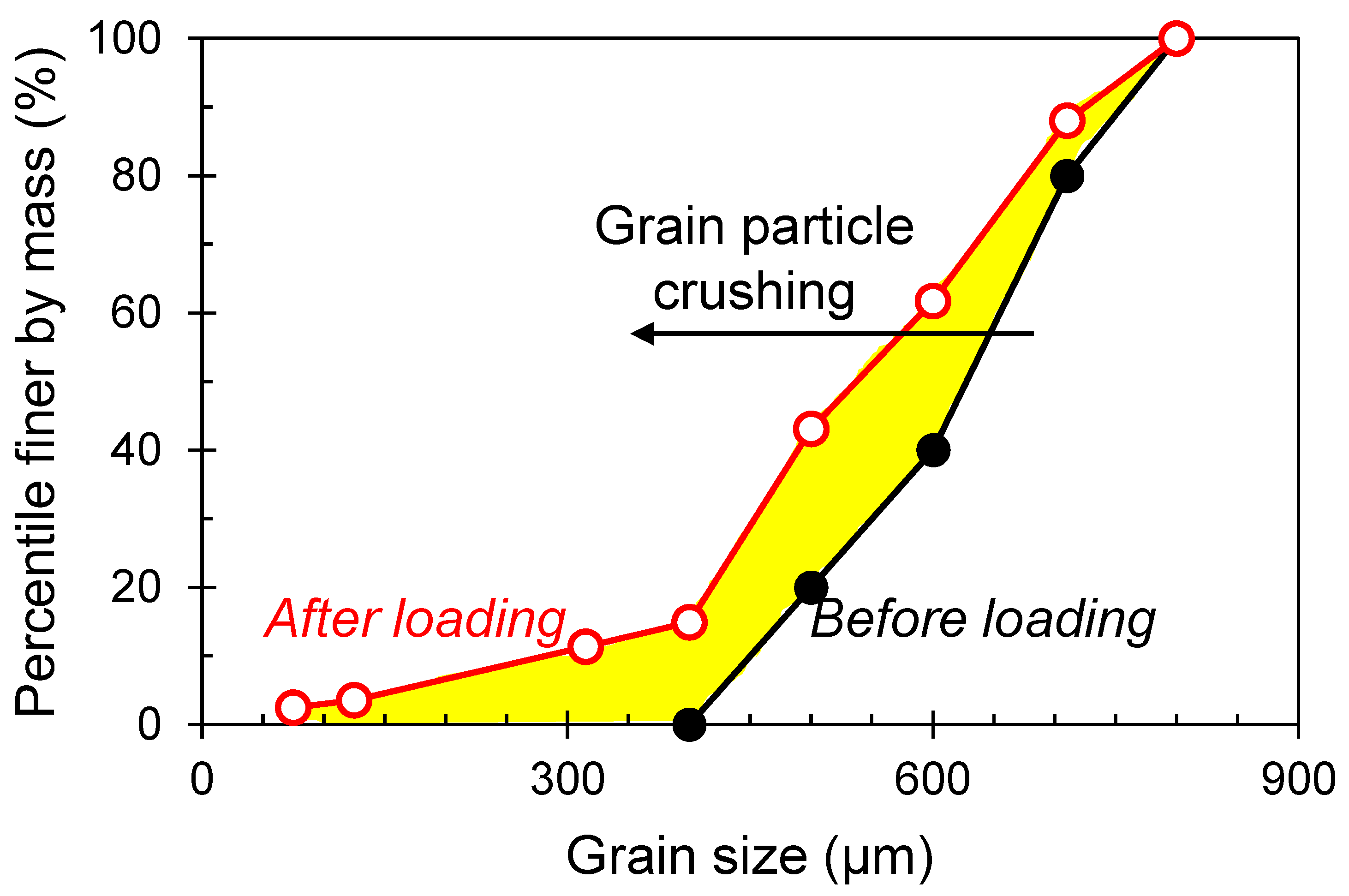

3. Results and Analysis

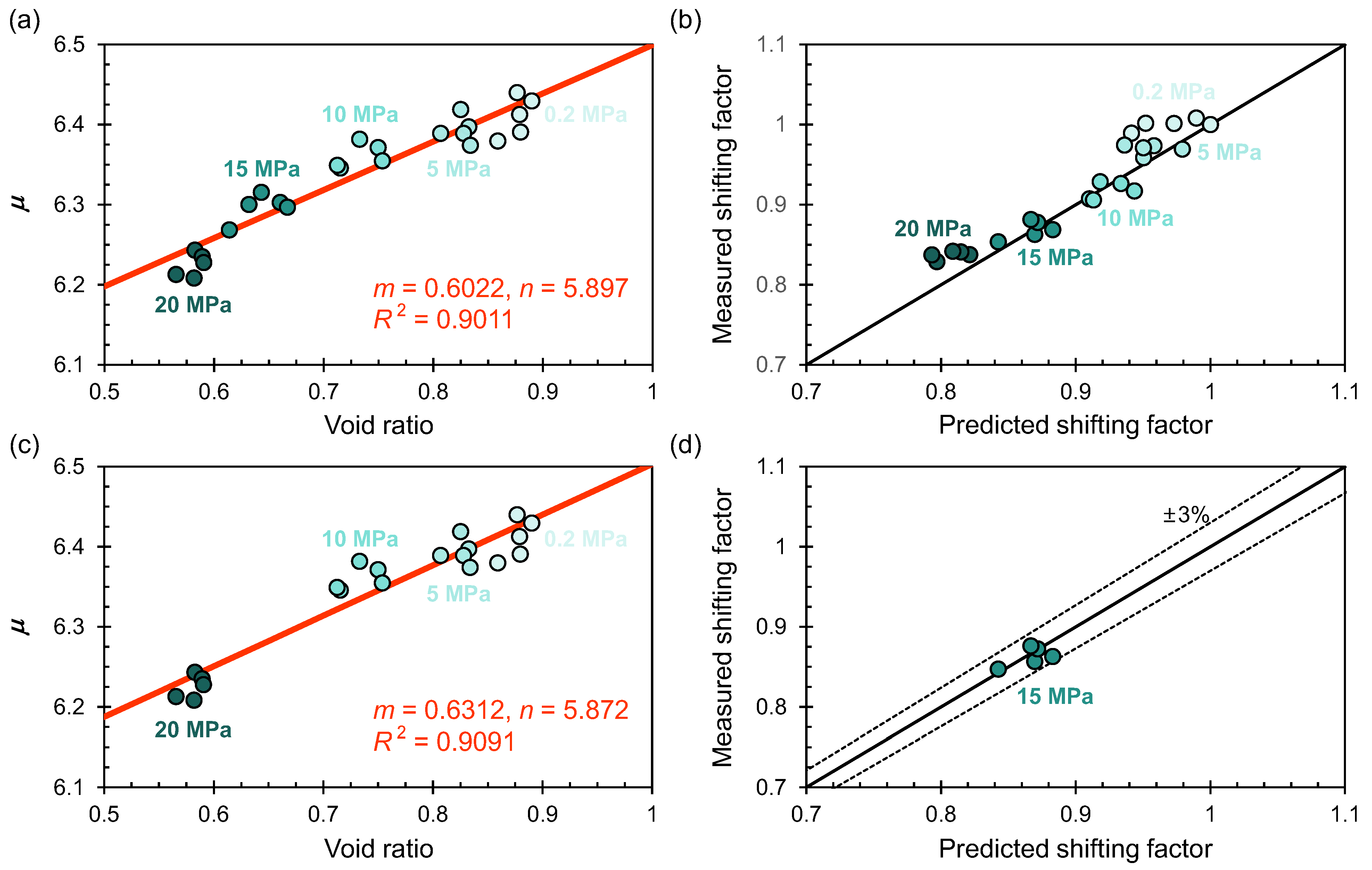

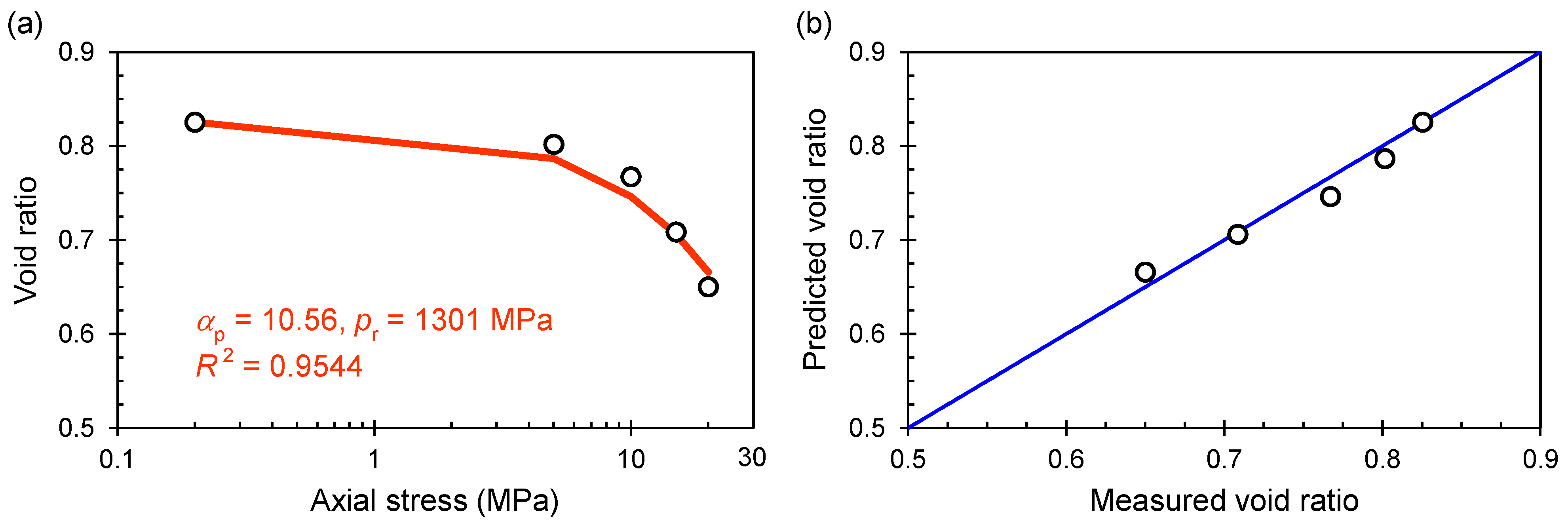

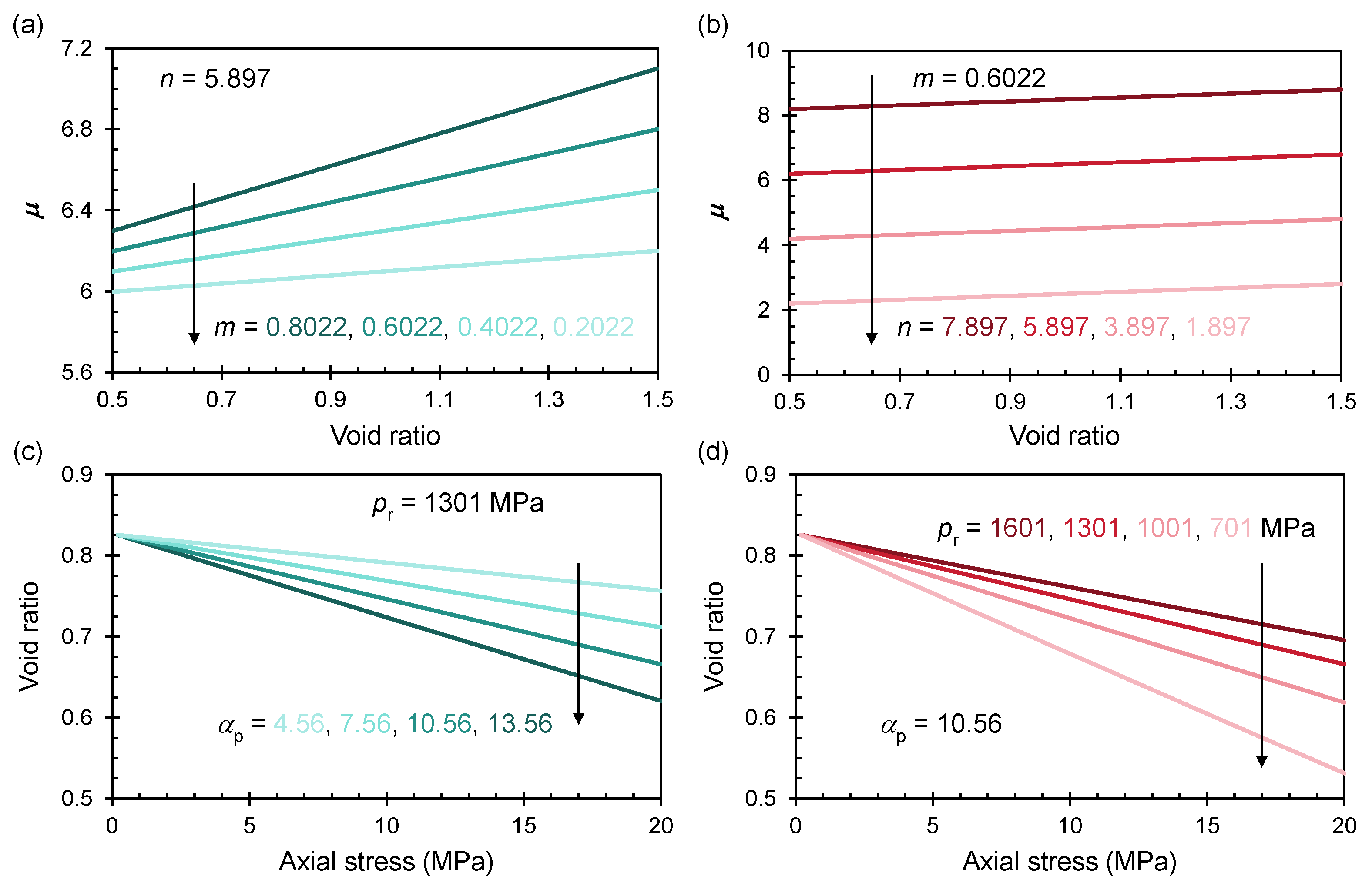

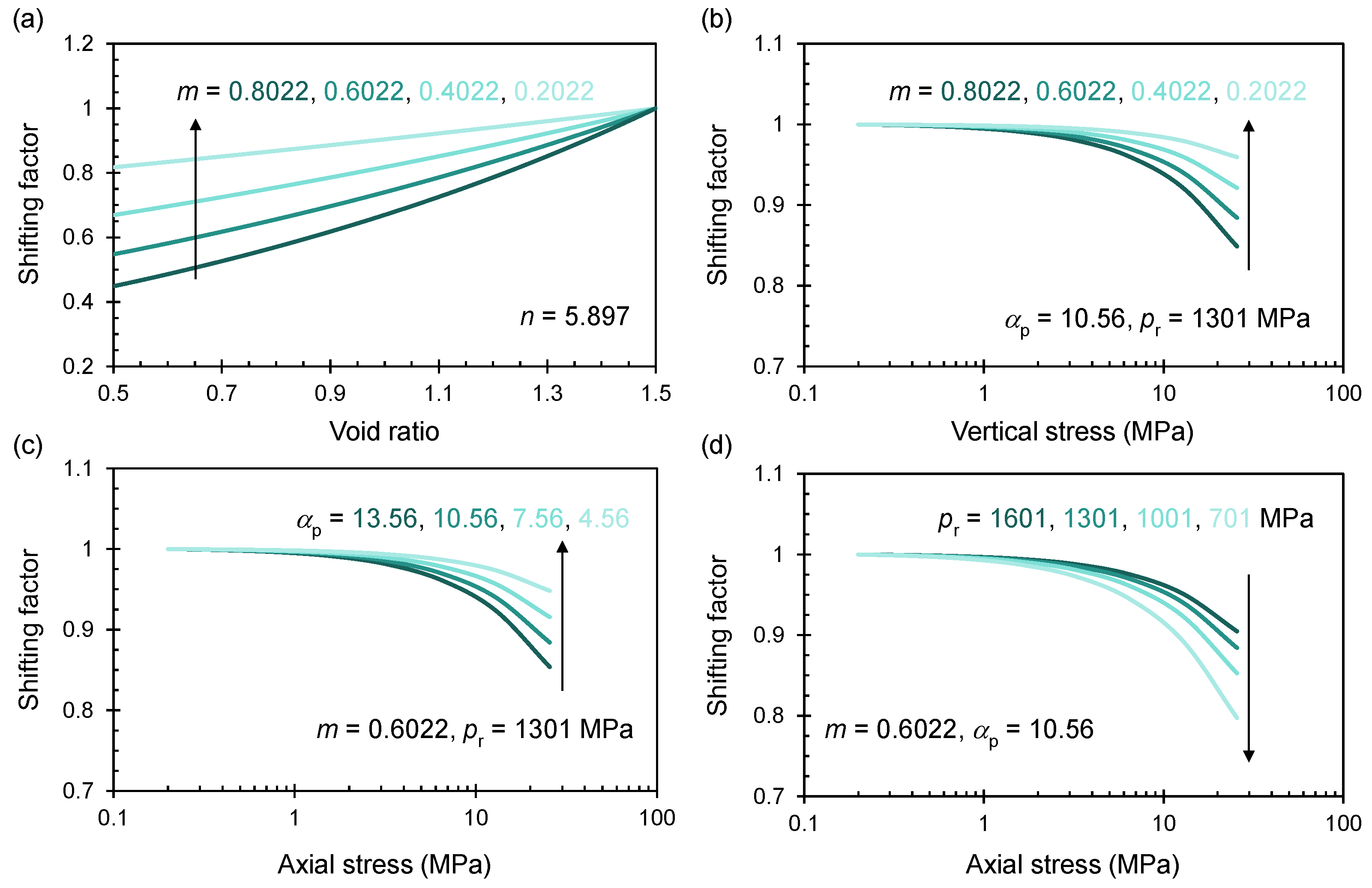

4. An Analytical Model of the Shifting Factor

5. Implications and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evro, S.; Oni, B.A.; Tomomewo, O.S. Global Strategies for a Low-Carbon Future: Lessons from the US, China, and EU’s Pursuit of Carbon Neutrality. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.C.; Holcombe, A.; Brown, S.; Ransley, E.; Hann, M.; Greaves, D. Evolution of Floating Offshore Wind Platforms: A Review of at-Sea Devices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; McMorland, J.; Zhang, H.; Collu, M.; Halse, K.H. Floating Offshore Wind Farm Installation, Challenges and Opportunities: A Comprehensive Survey. Ocean Eng. 2024, 304, 117793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Development of Offshore Wind Power and Foundation Technology for Offshore Wind Turbines in China. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerfontaine, B.; White, D.; Kwa, K.; Gourvenec, S.; Knappett, J.; Brown, M. Anchor Geotechnics for Floating Offshore Wind: Current Technologies and Future Innovations. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 114327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Jostad, H.P. Effects of Tension Gap on the Holding Capacity of Suction Anchors. Mar. Struct. 2020, 69, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Gilo, A.; Park, S.J.; Choo, Y.W. Centrifuge Model Test on the Bearing Capacity of Suction Anchors Subjected to Monotonic and Cyclic Inclined Pullout Loads in Clay. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Ma, H.; Yi, E.; Sun, K. Extraction of Suction Anchors in Sand with Overpressure-Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis. Ocean Eng. 2024, 297, 117058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Mu, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, M.; Huang, M.; Li, Y. Rate-Dependent Uplift Behavior and Soil Failure Mechanisms of Suction Anchors in Loose Sand: A Transparent Soil PIV Study. Ocean Eng. 2025, 341, 122555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Liang, R.; Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Inclined Pullout Capacity of Suction Anchors in Clay-Silty Sand-Clay Soil Deposits. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 158, 104549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Hossain, M.S.; Hu, Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Ullah, S.N. Failure Envelope of Suction Caisson Anchors Subjected to Combined Loadings in Sand. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 114, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yang, N.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, X. Inclined Pullout Capacity of Suction Anchors in Clay over Silty Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2023, 149, 4023030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbrich, C.T.; Tjelta, T.I. Installation of Bucket Foundations and Suction Caissons in Sand-Geotechnical Performance. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 3–6 May 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst, J.R. Field Trails with Large Diameter Suction Piles. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 5–8 May 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Harireche, O.; Mehravar, M.; Alani, A.M. Soil Conditions and Bounds to Suction during the Installation of Caisson Foundations in Sand. Ocean Eng. 2014, 88, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wu, S.-D.; Yang, J.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Chen, X. Failure Mechanism of Suction Anchor Based on FEM-SPH Method Considering Torsion Effect. Ocean Eng. 2025, 332, 121408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.H.; Jostad, H.P.; Dyvik, R. Penetration Resistance of Offshore Skirted Foundations and Anchors in Dense Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2008, 134, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.N.; Randolph, M.F.; Airey, D.W. Experimental Study of Suction Installation of Caissons in Dense Sand. In Proceedings of the ASME 2004 23rd International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–25 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R.B.; Houlsby, G.T.; Byrne, B.W. A Comparison of Field and Laboratory Tests of Caisson Foundations in Sand and Clay. Géotechnique 2006, 56, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.N.; Airey, D.W.; Randolph, M.F. Study of Seepage Flow and Sand Plug Loosening In Installation of Suction Caissons In Sand. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 19–24 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Senders, M.; Randolph, M.F. CPT-Based Method for the Installation of Suction Caissons in Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhao, L.; Luo, X.; Shi, Z.; Shen, K.; Wang, B. Evaluating Installation of Suction Caisson in Sand via Accounting for Soil Seepage-Deformation Coupled Process. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310, 118728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allersma, H.G.B. Centrifuge Research on Suction Piles: Installation and Bearing Capacity. In BGA International Conference on Foundations: Innovations, Observations, Design and Practice, Proceedings of the International Conference Organised by British Geotechnical Association, Dundee, UK, 2–5 September 2003; Newson, T.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7277-3904-9. [Google Scholar]

- Harireche, O.; Mehravar, M.; Alani, A.M. Suction Caisson Installation in Sand with Isotropic Permeability Varying with Depth. Appl. Ocean Res. 2013, 43, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mana, D.S.K.; Gourvenec, S.; Randolph, M.F. Numerical Modelling of Seepage beneath Skirted Foundations Subjected to Vertical Uplift. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 55, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Datta, M.; Gulhati, S.K. Pullout Behavior of Superpile Anchors in Soft Clay under Static Loading. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 1996, 14, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X. Effect of Partial Drainage on the Pullout Behaviour of a Suction Bucket Foundation. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 5322–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, Q.; Kang, J.; Li, D.; Wang, D. A Relation of Hydraulic Conductivity—Void Ratio for Soils Based on Kozeny-Carman Equation. Eng. Geol. 2016, 213, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Q.; Tang, X. Responses of Suction Buckets Subjected to Sustained Vertical Uplift Loads in Sand. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2022, 40, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Tang, X.; Uzuoka, R.; Luan, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, M. Suction Caisson Uplift Behavior in Multilayered Sand under Varying Drainage Conditions. Ocean Eng. 2025, 332, 121361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkunaite, E.; Nielsen, B.; Ibsen, L. Bucket Foundation Response under Various Displacement Rates. Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 2016, 26, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wu, K.; Luo, H.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Z.; Hao, D. Uplift Performance of Suction Foundations in Sandy Soils for Offshore Platforms. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 2845–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Ren, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Sun, Z. Micro-Macro Analysis of the Uplift Behavior of the Suction Anchor in Clay Based on the CFD-DEM Coupling Model. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 174, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augarde, C.E.; Lee, S.J.; Loukidis, D. Numerical Modelling of Large Deformation Problems in Geotechnical Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review. Soils Found. 2021, 61, 1718–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikura, Y. Estimation of Permeability for Sand and Gravel Based on Pore-Size Distribution Model. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 4019289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestel, J.; Dathe, A.; Skaggs, T.H.; Klakegg, O.; Ahmad, M.A.; Babko, M.; Giménez, D.; Farkas, C.; Nemes, A.; Jarvis, N. Estimating the Permeability of Naturally Structured Soil from Percolation Theory and Pore Space Characteristics Imaged by X-Ray. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 9255–9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhang, S. Modeling of Permeability for Granular Soils Considering the Particle Size Distribution. Granul. Matter 2023, 25, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Jeng, D.-S. Pore Scale Study of the Influence of Particle Geometry on Soil Permeability. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 129, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.-L.; Feng, X.-L.; Liu, L.-L.; Zhang, A.; Wang, D. Changes in the Effective Absolute Permeability of Hydrate-Bearing Sands during Isotropic Loading and Unloading. Pet. Sci. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Ning, F.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Hyodo, M.; Liu, C. Effect of Stress on Permeability of Clay Silty Cores Recovered from the Shenhu Hydrate Area of the South China Sea. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 99, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Zhou, C. A New Model for Water Retention and Hydraulic Conductivity Curves of Deformable Unsaturated Soils. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR037826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Ng, C.W.W.; Zhou, C.; Tang, C.S. A New Water Retention Model That Considers Pore Non-Uniformity and Evolution of Pore Size Distribution. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 5055–5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, M.; Donato, S.; Alessandro, F.; Campilongo, G.; Cianflone, G.; Costanzo, A.; Guido, A.; Lanzafame, G.; Magarò, P.; Maletta, C.; et al. Can Crystal Imperfections Alter the Petrophysical Properties of Halite Minerals? Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 168, 107013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Xu, X.; Yang, L. Experimental Study on Rebound and Recompression Deformation Characteristics of Different Soils. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Dai, S.; Jang, J.; Waite, W.F.; Collett, T.S.; Kumar, P. Compressibility and Particle Crushing of Krishna-Godavari Basin Sediments from Offshore India: Implications for Gas Production from Deep-Water Gas Hydrate Deposits. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 108, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.E.; Gens, A.; Josa, A. A Constitutive Model for Partially Saturated Soils. Géotechnique 1990, 40, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ng, C.W.W. A New and Simple Stress-Dependent Water Retention Model for Unsaturated Soil. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 62, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.-F.; Zhao, D.; Zeng, L.; Dong, H. A Pore Size Distribution-Based Microscopic Model for Evaluating the Permeability of Clay. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 5002–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Flury, M. Capillary Bundle Model of Hydraulic Conductivity for Frozen Soil. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Luo, L.; Ma, J.; Ji, Y.; Xiao, T.; Wu, N. Permeability Prediction in Hydrate-Bearing Sediments via Pore Network Modeling. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2025, 16, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlsby, G.T.; Byrne, B.W. Design Procedures for Installation of Suction Caissons in Clay and Other Materials. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Geotech. Eng. 2005, 158, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlsby, G.T.; Byrne, B.W. Design Procedures for Installation of Suction Caissons in Sand. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Geotech. Eng. 2005, 158, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y. Penetration Behaviors and Soil Plug Developing of the Scaled Suction Caisson during Installation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310, 118737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Hossain, M.S.; Kim, Y.; Ullah, S.N.; Hu, Y. Installation and Inclined Loading of a Suction Caisson Anchor in Calcareous Sand. Ocean Eng. 2025, 316, 119997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.X.; Hossain, M.S.; Kim, Y. Installation and Monotonic Pullout of a Suction Caisson Anchor in Calcareous Silt. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2017, 143, 4016098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-H.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Fu, Y. Numerical Investigation on the Pull-out Capacity of Suction Anchors in Sand Considering Torsional and Mooring Line Effects. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 160, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.-T.; Ji, C.-L.; Liu, L.-L.; Ma, H.-L.; Fu, D.-F. Pore Structure Evolution in Marine Sands Under Laterally Constrained Axial Loading. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122367

Zhang X-T, Ji C-L, Liu L-L, Ma H-L, Fu D-F. Pore Structure Evolution in Marine Sands Under Laterally Constrained Axial Loading. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122367

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xia-Tao, Cheng-Liang Ji, Le-Le Liu, Hui-Long Ma, and Deng-Feng Fu. 2025. "Pore Structure Evolution in Marine Sands Under Laterally Constrained Axial Loading" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122367

APA StyleZhang, X.-T., Ji, C.-L., Liu, L.-L., Ma, H.-L., & Fu, D.-F. (2025). Pore Structure Evolution in Marine Sands Under Laterally Constrained Axial Loading. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122367