1. Introduction

As a crucial component of transportation, shipping plays a significant role in bulk cargo transport due to its advantages of low cost and high capacity. The rapid development of the shipping industry has promoted high-quality regional economic growth, but has also led to increased air pollutant emissions from ships. Statistics indicate that global ship emissions contribute approximately 15% of NO

X and 8% of SO

X emissions [

1,

2]. Excessive air pollution can cause cardiovascular diseases, bronchitis, emphysema, and even lead to lung cancer, posing serious threats to the health of coastal populations. Simultaneously, SO

2 pollution can cause acid rain, which corrodes public facilities and damages ecosystems [

3]. The challenge of real-time monitoring of SO

2 and other ship-emitted pollutants, and of effectively identifying fuel with excessive sulfur content, is a crucial and urgent task to maximize the impact of emission control areas [

4,

5,

6].

Traditional methods for supervising ship exhaust emissions have significant shortcomings. Approaches relying on manual boarding inspections and fuel sampling analysis are inefficient, have limited coverage, and pose considerable challenges for monitoring ships underway. In recent years, monitoring methods based on sniffer technology and optical remote sensing have improved efficiency to some extent but still suffer from issues, such as monitoring accuracy that is greatly affected by meteorological conditions and the inability to accurately identify single emission sources [

7,

8,

9]. Against this backdrop, remote monitoring technology for ship exhaust based on AIS information has emerged for real-time calculation and traceability of ship emissions [

10,

11,

12].

Ship emission calculation methods form the basis for studying ship air pollution and have evolved from macro-estimation to refined calculation. Early research primarily used “top-down” approaches to estimate emissions based on fuel consumption. However, “top-down” methods have limitations such as low spatial accuracy and an inability to distinguish operating modes [

13]. With the popularization of AIS information, the “bottom-up” activity-based approach has gradually become mainstream [

14]. In this approach, ship design parameters such as main engine power, auxiliary engine power, and design speed are important factors that affect the model’s calculation accuracy. Existing research mainly employs four methods: retrieval from classification society databases, questionnaires, regression prediction, and empirical value assignment [

15,

16,

17,

18]. For instance, Goldsworthy et al. [

15] used the Lloyd’s Register database to establish an emission inventory for the seas around Australia.

Gas dispersion models are essential tools for studying pollutant transport and distribution. In ship exhaust dispersion research, Gaussian models are widely used for their computational simplicity and broad applicability. However, most existing studies treat ships as fixed emission sources, neglecting their moving characteristics [

19]. Recently, scholars have begun to focus on the exhaust dispersion characteristics of ships underway. Tang [

20] established a wind-oriented coordinate system that accounts for ship speed, transforming moving sources into fixed-point sources for study; Gan et al. [

21] used the Gaussian puff model to simulate ship exhaust dispersion in Shenzhen Port. However, existing studies directly use ground-level wind speed without accounting for the difference in wind speed at the emission source height. In addition, practical methods for synthesizing concentration fields from multiple overlapping dispersion sources are lacking.

The goal of ship exhaust monitoring is not only to detect suspected non-compliant ships but also to accurately identify and match the responsible ship. Existing matching methods primarily operate at three levels: concentration contribution analysis, trajectory similarity calculation, and the application of intelligent algorithms [

22,

23,

24]. In concentration contribution analysis, early research often used contribution ranking methods based on dispersion simulation. While intuitive, this method suffers from high misjudgment rates in inland waterway environments with multiple ships and variable wind directions, due to difficulties in accurately simulating multi-source overlapping dispersion [

25]. In trajectory and concentration sequence similarity analysis, scholars have begun exploring the use of time series similarity for refined ship matching. Langella et al. used the Pearson correlation coefficient to assess the correlation between simulated and measured concentration sequences, identifying the ship with the highest correlation coefficient as the most suspicious target [

26]. Although correlation analysis is computationally efficient, it is insensitive to amplitude differences between sequences, potentially leading to false matches when simulated concentrations are generally low but highly correlated with measured sequences. With the rise in intelligent algorithms, machine learning, and data fusion techniques have been introduced to address the complexity of matching [

27]. However, it requires a large number of confirmed exceedance cases as labeled data for supervised learning, which poses challenges for practical application due to sample scarcity. Grey system theory has shown potential for environmental traceability due to its ability to handle uncertainty with limited data and poor information. Grey relational analysis assesses the degree of association by measuring the similarity of the geometric shapes of sequence curves and imposes no strict requirements on data distribution. For example, Huang and Wu proposed a method combining dynamic thresholds adapted to multiple scenarios with relational analysis, providing an entry point for the systematic application of grey relational analysis to match ship underway exhaust emissions [

25,

28].

In practical navigation environments, simultaneous exhaust emissions from multiple ships are widespread. This multi-ship emission scenario presents challenges for concentration matching and inversion calculation. When only one ship passes the monitoring point, the monitored concentration minus the background concentration can be equated to the real contribution concentration of that ship’s exhaust. Based on this concentration, source strength inversion and sulfur content back-calculation can be performed to determine the ship’s fuel sulfur content and further identify whether it is a suspected violator. However, when multiple ships pass near the bridge simultaneously, the monitored pollutant concentration reflects the combined emissions from these ships. Therefore, directly attributing the monitored concentration value after background subtraction to a single ship’s emissions is inaccurate. Because the emission source strength of each ship is unknown and emission characteristics vary with factors such as ship type, fuel type, speed, and operating conditions, accurately allocating the monitored concentration to specific ships is difficult [

28,

29].

In light of these considerations, this study examines a monitoring and matching method for excessive ship emissions based on AIS data. This method applies a ship emission calculation model to obtain real-time SO2 emission source strength for each ship. An improved Gaussian puff model that accounts for the moving characteristics of ships is established to calculate time-series SO2 diffusion concentrations at monitoring points for each ship within the study area. Furthermore, a matching algorithm for identifying ships with excessive emissions based on grey relational analysis is designed to match the calculated time-series diffusion concentration of each ship with the actual monitored concentration, achieving precise traceability of ships with excessive emissions under multi-ship conditions. This study uses the Yangtze River waterway at the Nanjing Dashengguan Yangtze River Bridge as the empirical area to validate the method’s feasibility and effectiveness. The research results can not only improve the efficiency and accuracy of ship emission supervision but also provide critical technical support for the green development of shipping and air pollution prevention and control.

2. Methodology

This study proposes a hybrid method for monitoring and matching ships with excessive emissions. The method consists of three parts: (1) using a ship emission calculation model to obtain the real-time SO2 emission source strength for each ship; (2) based on the calculated emission source strength, combined with a Gaussian puff model, obtaining the SO2 diffusion concentration from these ships at monitoring points; and (3) using a grey relational analysis method to match the calculated time-series concentration of each ship with the actual monitored concentration to identify ships violating emission standards.

2.1. Ship Emission Calculation Model

Gaseous pollutants emitted by ships are primarily generated by the operation of the main engine and auxiliary engines. The main engine provides the power required for ship propulsion, while the auxiliary engines supply the necessary electricity for the entire vessel. The operational conditions (i.e., load status) of both change with the ship’s sailing status. By analyzing the sailing status data, the specific SO

2 emission can be calculated using the following formula:

In the equation,

represents the type of engine, including the main engine and auxiliary engines;

represents the SO

2 emission (g);

represents the continuous operating time of the engine (h);

represents the SO

2 emission factor (

). The SO

2 emission factor is directly related to the engine type, fuel type, and fuel sulfur content. When the fuel sulfur content is around 0.1%, the emission factors can be taken as: 0.38

for main engines using high-speed engines; 0.42

for main engines using medium-speed/low-speed engines; and 0.42

for auxiliary engines using high-speed engines. According to the relevant literature, the main engines of inland waterway ships primarily use medium-speed engines, while auxiliary engines generally use high-speed engines [

25,

30].

represents the engine’s rated power (

). Due to the difficulty of obtaining real-time power data from ship engine rooms, main and auxiliary engine power can be estimated based on ship gross tonnage using multi-source data-matching and regression-fitting methods, as shown in

Table 1 [

31,

32]. The regression equations between gross tonnage and main engine power in the table were established by Chen et al. [

31] based on a comprehensive selection of 406,616 different types of ships from the Yangtze River Basin, the Pearl River Basin, and the Bohai Sea area in China, demonstrating strong representativeness.

represents the engine load factor, which is an indicator measuring the actual load level of the ship’s engine during operation. The auxiliary engine load factor is closely related to ship type and sailing speed, as shown in

Table 2 [

33]. It should be noted that directly measuring the load factor and fuel flow rate from shipboard instruments would provide the most accurate data for emission calculations. However, acquiring real-time, ship-specific engine performance data poses significant practical challenges for large-scale maritime monitoring applications. Due to issues with data accessibility, technical integration, and the heterogeneity of shipboard monitoring systems across different ships and operators, direct measurements are currently not feasible for the scope of this study. Therefore, in line with established practices in regional and port-level ship emission studies, this study adopts the widely recognized speed-load relationship, in which the load factor is estimated as the cube of the ratio of the actual speed to the design speed. This approach, while an approximation, has been extensively validated and applied in numerous authoritative studies to derive representative emission estimates in data-scarce environments [

34]:

In the equation,

represents the ship’s actual sailing speed (knots);

represents the ship’s design speed or maximum speed (knots). The actual speed can be obtained from AIS data. The average design speed or maximum speed can be taken as follows: cargo bulk carrier, 15 knots; cargo oil tanker, 15 knots; cargo container, 21 knots; passenger, 21 knots; other types of ships, 15 knots [

28].

2.2. Gaussian Puff Diffusion Model

The Gaussian diffusion model assumes that pollutant concentrations follow a normal distribution and is suitable for simulating the diffusion of small and medium molecular weight gases. Its applicable scale matches the scenario of ship exhaust emission monitoring. The Gaussian puff model approximates the smoke emitted by a ship at a specific moment as an instantaneously released point source, which can reasonably describe the unsteady diffusion of smoke from instantaneous emissions during ship movement. Therefore, this model is more adept at capturing the instantaneous diffusion characteristics of smoke plumes. Especially when considering dynamic factors such as ship motion and changes in wind speed, discretizing continuous emissions into a series of instantaneous puffs can more accurately simulate diffusion behavior shortly after emission, thereby better reflecting the actual situation.

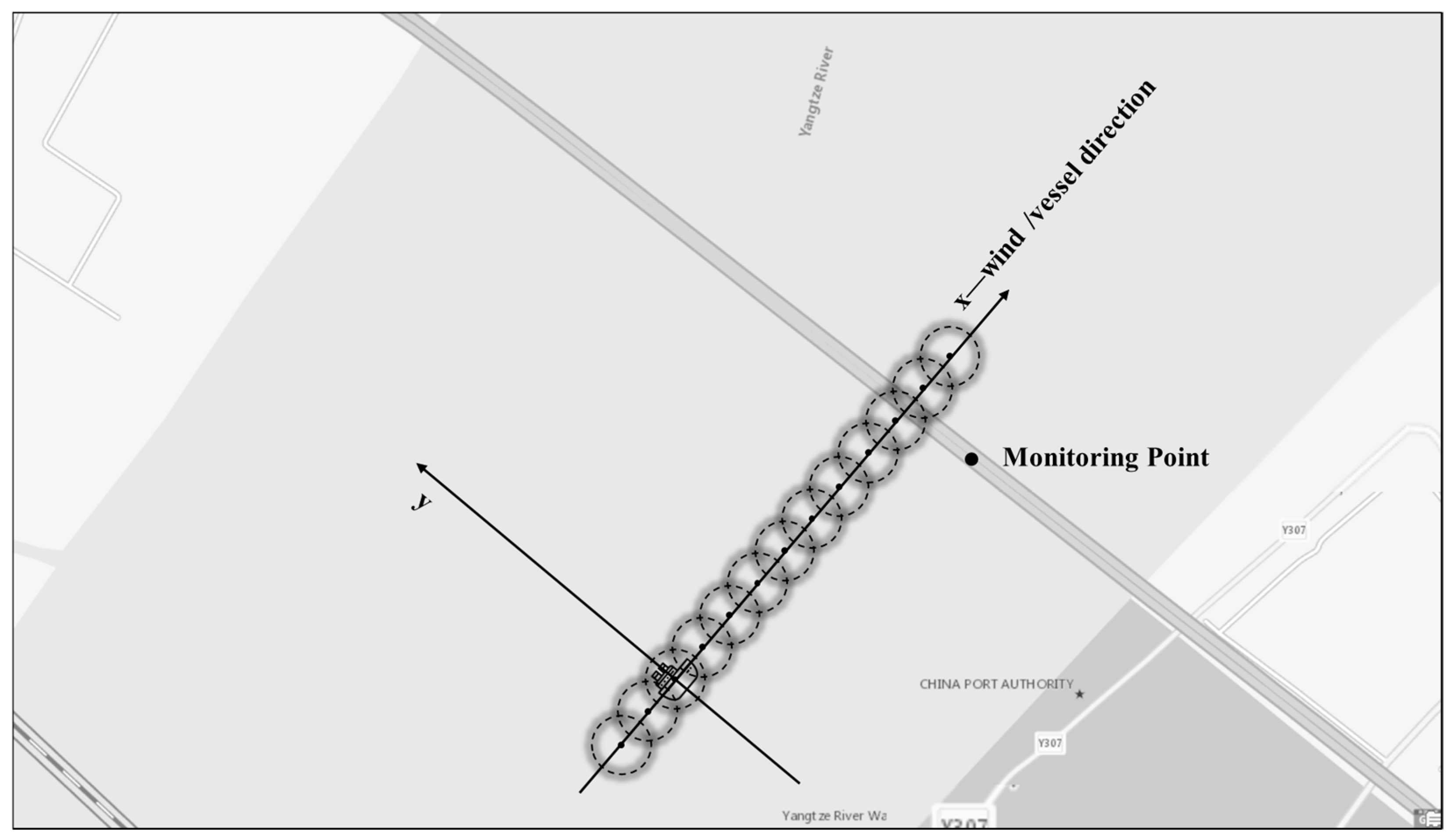

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of a moving ship emission source and a monitoring point in the Gaussian puff model. Ship exhaust emissions can be simplified as an instantaneous point source moving along a straight horizontal line. Because each puff is instantaneous in time and discrete in space, this characteristic allows the Gaussian puff model to better represent the instantaneous and spatially heterogeneous nature of ship exhaust diffusion. Therefore, this model is suitable for instantaneous or short-term emission scenarios and emphasizes the impact of time on changes in pollutant concentrations.

The Gaussian puff model assumes that pollutants are released into the atmosphere instantly in a specific volume or mass. After release, diffusion occurs in both horizontal and vertical directions, effectively simulating the initial stage of pollutant diffusion. In this study, continuous exhaust emissions from navigating ships were discretized into a series of instantaneous puffs at a 1 s time resolution. This choice was based on a balance between computational accuracy and efficiency. Given the sailing speeds and spatial scale of the study area around the bridge, a 1 s interval ensures that the displacement of a ship between successive puffs is enough to accurately represent its moving trajectory as a continuous emission source. A finer resolution would significantly increase computational load without providing a commensurate improvement in the simulated concentration field at the monitoring point, which has a data sampling frequency of 5–10 s. The Gaussian puff diffusion model can be expressed as:

In the equation,

represents the SO

2 diffusion concentration from the ship at a downwind monitoring point (

);

Q represents the emission source strength of the ship (

;

t is the emission time of the ship’s exhaust source, i.e., the ship’s travel time (s);

H is the effective height of the emission source (m);

is the wind speed at the effective height, i.e., the wind speed at the ship’s stack outlet (m/s);

,

, and

are the diffusion coefficients in the

x (downwind),

y (crosswind), and

z (vertical) directions. Dispersion coefficients in atmospheric dispersion models depend on atmospheric stability and downwind distance. Traditional empirical methods can characterize gas dispersion over long distances, but they lack resolution and accuracy for small-scale dispersion, such as ship pollutant emissions. Thus, the traditional empirical dispersion coefficient equation is modified by introducing different directional dispersion coefficients:

where x represents the downwind distance from the emission source (m);

and

are the horizontal dispersion coefficients;

and

are the vertical dispersion coefficients;

and

are the dispersion indices. The values can be obtained from the Briggs dispersion coefficient equations [

1,

35], as shown in

Table 3.

Variables such as wind speed and the emission source height during ship exhaust diffusion not only affect the dispersion range and concentration distribution but also determine the potential environmental impact. Therefore, in practical emission environments with complex meteorological conditions and dispersed ship movements, corrections are necessary based on the characteristics of ship exhaust emissions. As the emission source height increases, the dilution effect of the exhaust in the atmosphere also enhances, leading to a significant reduction in pollutant concentration at the monitoring level. This effect is particularly prominent for different types of ships and emission source heights [

36]. The effective height of the emission source can be expressed as the geometric height of the ship’s stack plus the plume rise of the ship’s exhaust. Due to the numerous parameters required to calculate ship exhaust plume rise and the difficulty in obtaining them, limited by a lack of practical data, values recommended in the literature can be adopted [

20].

Furthermore, the model uses real-time wind speed at the emission source, which may differ from ground-level wind speed. The influence of wind speed at different heights can be significant, necessitating wind speed correction:

In the equation,

is the ground-level wind speed (m/s);

is the monitoring height of the ground-level wind speed (m);

m is the power-law constant determined by the atmospheric stability class. Atmospheric stability is a measure of the vertical consistency of the atmosphere, reflecting the degree of turbulence present. A higher level of stability reduces the potential for air to spread. Atmospheric stability depends on several factors, such as observation time, solar hour angle, solar dip angle, solar altitude angle, cloud cover, solar incidence class, and wind speed. Initially, the solar hour angle is computed from the local longitude and the timing of the observation. Following this, the solar altitude angle is calculated based on the solar hour angle, solar dip angle, and local latitude. The solar incidence classification is established by analyzing the solar altitude angle along with cloud cover. Finally, the atmospheric stability class is ranked from grade A to F, where A indicates a high degree of instability, and F denotes complete stability. The method for determining atmospheric stability is described in the relevant literature [

20].

2.3. Multi-Ship Exhaust Monitoring Concentration Matching Method Based on Grey Relational Analysis

Historical data analysis reveals that while a single ship typically accounts for exhaust monitoring readings at any given time, multi-ship influences, where two or three ships collectively impact emission data, occur in approximately 30% of instances. When multiple ships traverse a monitoring point simultaneously or in close succession, conventional inversion methods fail to account for multi-source superposition effects, leading to significant deviations in back-calculated results. Consequently, in practical applications, sulfur content evaluation is generally avoided during such multi-ship scenarios to prevent inaccurate assessments.

To address the matching problem, this study analyzes the extent to which the monitored concentration value is influenced by exhaust from different ships. Specifically, when multiple ships pass by, the monitored SO2 concentration is attributed to emissions from all ships. By combining ship trajectories, meteorological conditions, and emission models, concentration curves for each ship are generated and compared with the monitored concentration curve, ultimately achieving ship concentration matching. The grey relational analysis method can effectively solve the above problems.

Grey relational analysis is an important analytical tool in grey system theory, primarily used to handle complex problems with unclear internal relationships and incomplete information within a system. It is suitable for analyzing the interrelationships among multiple factors, especially when data are limited or samples are uncertain, demonstrating good adaptability. The core idea of grey relational analysis is to assess the relationship between two sequences by comparing the geometric shapes of their trajectories. If the trend of two sequences is similar, their correlation is high; if they differ, their correlation is low. The general analytical steps of the grey relational analysis method are as follows:

- (1)

Determine the reference sequence and comparison sequence. The reference sequence typically represents the ideal state or target value of the system; the comparison sequence is the objects within the system that need to be compared and analyzed.

- (2)

Data dimensionless processing. To eliminate the effects of different dimensions or numerical differences, data usually need to be dimensionless processed, such as by initial-value processing or range normalization.

- (3)

Calculate the correlation coefficient between sequences. By calculating the difference between the reference sequence and the comparison sequence at each time point, and converting it into a correlation coefficient using the following formula:

In the equation, is the correlation coefficient at time k, representing the degree of correlation between the reference sequence and comparison sequence at this time point; represents the absolute difference between the reference sequence and the comparison sequence at time k; the minimum value of the absolute differences across all times is , and the maximum value is ; is the resolution coefficient, which adjusts the weight of the minimum and maximum differences in the calculation of the correlation coefficient, increasing the system’s sensitivity to extreme value differences. The resolution coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, usually set to 0.5, to avoid overemphasizing or diminishing the influence of the maximum difference.

- (4)

Calculate the grey relational grade. The relational grade is the average of the correlation coefficients, used to measure the overall degree of correlation between two sequences:

In the equation, represents the grey relational grade; n is the sequence length, representing the number of data points in the sequence.

- (5)

Analyze the results. Evaluate the correlation among various factors in the system using the grey relational grade. A larger relational grade indicates that the change trends of the two sequences are more similar, and the correlation is stronger.

The reference sequence can be expressed as:

The comparison sequence can be expressed as:

The formulas for the correlation coefficient and relational grade between the reference sequence and comparison sequence are:

In the equation, is the absolute value of the difference sequence at time k; is the two-level minimum difference; is the two-level maximum difference.

When more than one ship passes the monitoring point, the ship concentration matching calculation is required. The matching process is as follows:

- (1)

Define a matching time window. Determine the start time and end time of the matching period based on the peak concentration.

- (2)

Determine the comparison sequence and reference sequence. Calculate the time-series diffusion concentration of SO2 from each ship diffusing to the monitoring point as the comparison sequence, where m is the number of time points in the diffusion concentration time series within the matching period. The reference sequence is composed of the actual monitored concentration minus the SO2 background concentration, representing the true contribution concentration.

- (3)

Calculate relational grade. Use the grey relational analysis method to calculate the relational grade between each ship’s diffusion concentration sequence and the reference sequence . For benchmarking, a ship with a diffusion concentration always equal to 0 needs to be included in the comparison sequence, and its calculated relational grade is

- (4)

Calculate ship matching probability. The benchmark ship, with a diffusion concentration of 0, also has a ship-matching probability of 0. Using this benchmark value, the matching probability for other ships is calculated through interpolation.

- (5)

Ship matching determination. Based on the relevant literature, in this study, a ship with a matching probability exceeding 70% is identified as the ship currently exerting the primary influence on the concentration change. If no ship’s matching probability exceeds 70%, it is considered that the ship corresponding to the monitored concentration cannot be identified within the current time period [

25,

28].

3. Data Collection and Preprocessing

In a previous engineering application by the research team, a spectral analysis-based remote sensing system was deployed at the Nanjing Dashengguan Yangtze River Bridge in 2021. This bridge links Pukou District with Nanjing’s main urban area, China. The installed system enables real-time collection and monitoring of pollutant emissions concentration data from ships. The Nanjing Dashengguan Yangtze River Bridge features a navigational clearance width of 650 m. The transmitter for the monitoring system is mounted on the bridge deck above the upstream channel, while the receiver is located on the maintenance platform of the northern tower. With a total optical path of about 350 m, the setup provides adequate monitoring coverage for vessels traveling upstream. A dedicated 4G network on the bridge ensures stable data transmission for the spectral monitoring devices. As shown in

Figure 2, the equipment comprises three main components: an analyzer unit, a light emitter, and a light receiver. A xenon lamp in the transmitter produces a light beam directed toward the detector, establishing an unobstructed optical pathway. The analyzer identifies and quantifies specific substances by assessing the absorption characteristics they exhibit in the detected spectrum.

The data collected in this study are primarily categorized into three types:

- (1)

Ship AIS data, which consists of both static information and real-time dynamic data. Static data includes ship name, Maritime Mobile Service Identify (MMSI), and vessel type. Real-time dynamic data comprises current latitude and longitude, navigation status, speed over ground, and course over ground. Due to high vessel traffic density in the waterways, potential human operational errors, and equipment or system malfunctions, the collected AIS data may contain missing values or anomalies. Direct utilization of such unprocessed data for emission calculations would compromise the accuracy and reliability of the results. It is essential to perform preliminary data preprocessing, including correcting or removing outliers and applying interpolation techniques to address missing data. The specific criteria and procedures applied are summarized as follows: (1) Validity and format filtering. The raw AIS data were checked for valid formatting and completeness. Records with missing critical fields, specifically MMSI, position, timestamp, and sailing speed, were discarded. (2) Duplication removal. Duplicate AIS messages, defined as records with identical MMSI, timestamp, and position, were identified and removed to ensure that each data point represented a unique vessel state. (3) Outlier removal. To remove implausible data, sailing speeds were constrained to a realistic range for inland waterway navigation. Records indicating a sailing speed of less than 0.5 knots (considered drifting or stationary for practical purposes) or greater than 30 knots (an unrealistic high speed for this inland context) were excluded. (4) Interpolation processing for gap-filling. A linear interpolation scheme was applied to the AIS dataset to achieve uniform 1 s time steps, thereby facilitating subsequent computational procedures.

- (2)

Wind speed and direction data are acquired using an anemometer, enabling real-time measurement and continuous monitoring of wind variations. The anemometer has a maximum measurable wind speed of 60 m/s and offers 360-degree coverage for wind direction, with an accuracy of ±3 degrees and high resolution. To quantify the potential effects of wind speed and direction, this study conducted a perturbation analysis of Gaussian model parameters. The results indicate that a wind direction perturbation within ±5° leads to only minor changes in the calculated concentration time series and has a negligible impact on the final matching probability. More significant fluctuations in wind direction will be the focus of a dedicated investigation in future research.

- (3)

Ship exhaust SO2 concentration data are collected by a differential optical absorption spectrometer (DOAS) installed on the Nanjing Dashengguan Yangtze River Bridge, with a monitoring frequency of 5–10 s. This instrument utilizes the narrowband absorption characteristics of gas molecules to identify gas types. It quantifies concentrations based on absorption intensity, offering advantages such as wide coverage, high sensitivity, and strong stability. The calibration of the DOAS system was conducted using a standard reference gas. The DOAS system undergoes regular calibration (e.g., quarterly or before critical measurement campaigns) using certified SO2 reference gases with known concentrations. This procedure is designed to verify the system’s linear response and detection sensitivity, and to correct for potential optical drift or systematic errors.

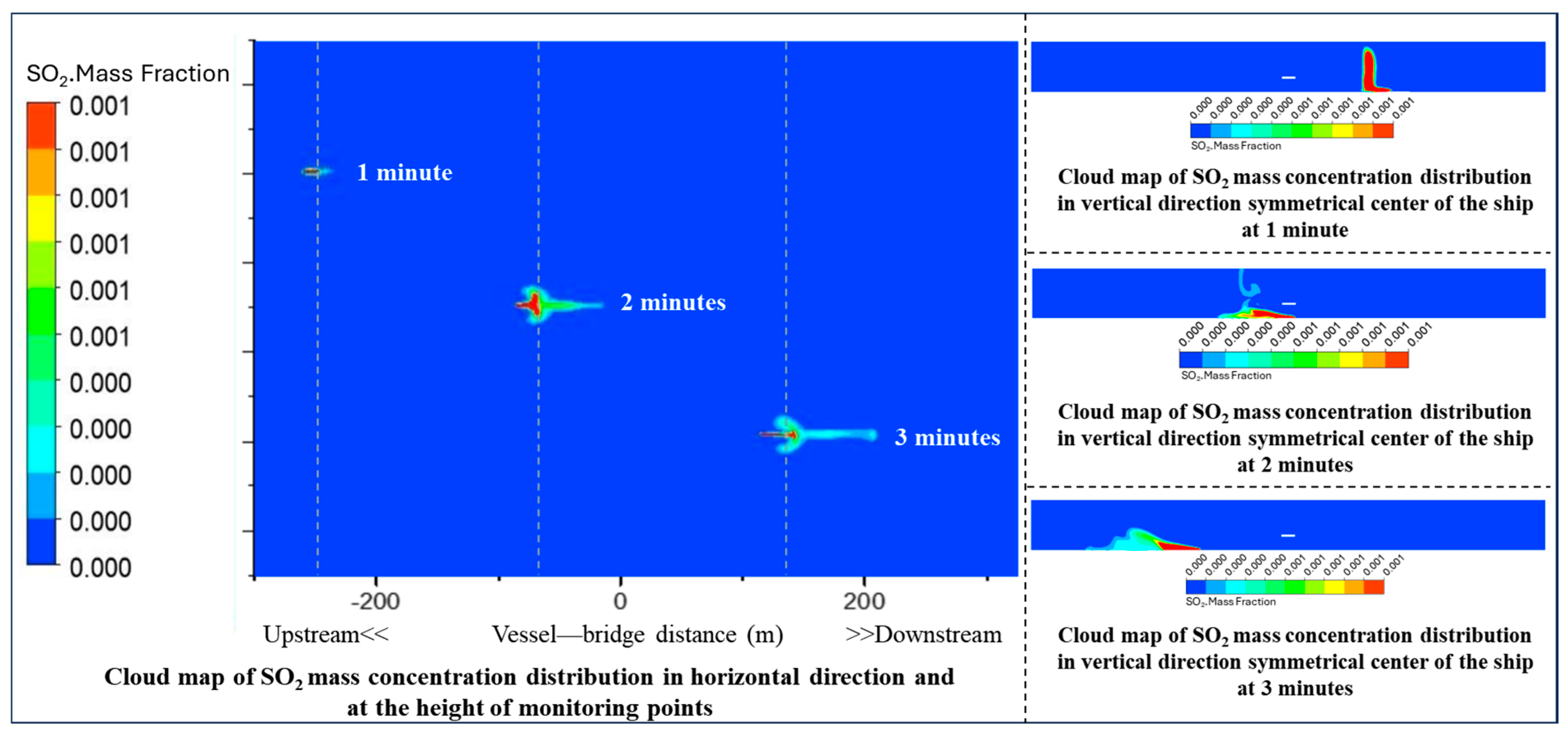

To visually characterize the spatial distribution of SO

2 dispersion at different time intervals, horizontal cross-sectional concentration maps at monitoring point height and vertical concentration profiles along the ship’s central axis were plotted after 1, 2, and 3 min of vessel operation, as shown in

Figure 3. A comparison of these spatial distributions reveals that SO

2 diffusion from the navigating ship is non-stationary, with a clear positive correlation with emission duration. As the vessel proceeds, the affected area of SO

2 emissions expands. The SO

2 released by the ship forms a concentration gradient each minute, with longer emission times leading to greater influence from exhaust plume dispersion and consequently higher monitored SO

2 levels. This indicates that emission duration is a significant factor influencing SO

2 diffusion. Although the overall shape of the horizontal concentration distribution at the monitoring height appears similar across different time points, the magnitude of diffusion concentration varies substantially. In the downwind direction, due to the combined effects of wind and ship speed, the diffusion range of SO

2 is considerably larger than in other directions. Meanwhile, the extent of diffusion perpendicular to the wind direction shows a symmetric pattern, with a relatively slower diffusion speed and a lower mass concentration distribution. Therefore, the combined influence of wind and vessel speed also plays an essential role in the dispersion of SO

2 from ships.

4. Results Analysis

To illustrate and validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, three sections were presented in this study: (1) To verify the feasibility and accuracy of the ship matching method in practical applications, this study randomly selected three effective matching cases (including frequent peaks scenario, and sparse but conspicuous peaks scenario) of ships with excessive emissions from the monitoring area of the Nanjing Dashengguan Yangtze River Bridge. (2) Using the information on 97 exempted ships provided by the maritime authorities to validate the effectiveness of the excessive ship exhaust emissions monitoring and matching. (3) To evaluate the robustness of this method, an uncertainty analysis for several key parameters is conducted, such as the emission factor, AIS errors, and wind direction.

4.1. True Contribution Concentration of Ship Exhaust Emission

When a ship approaches the monitoring point, distinct fluctuations in SO2 concentration occur, producing peak concentrations. However, this peak concentration cannot be used directly as the monitored concentration to match ships with excessive emissions, because SO2 remains in the atmosphere even when no ships are present. This concentration is known as the ambient or background concentration. Therefore, the background concentration must be removed before ship matching.

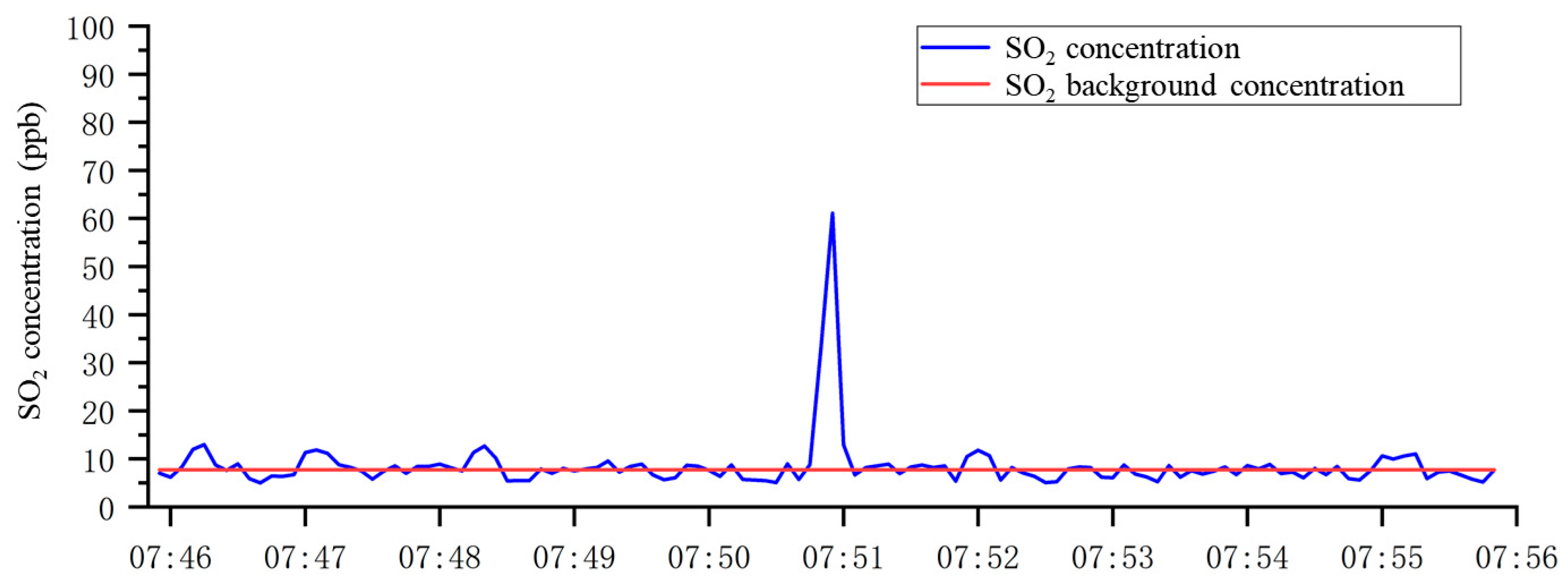

Figure 4 shows the monitored SO

2 concentration data at the monitoring point from 7:46 to 7:56 on 17 March 2022. The true contributions of SO

2 are obtained by removing the background concentration. In a laboratory setting, the background concentration would be the average value after removing the peak concentrations. However, in practice, multiple ships pass by alternately, interfering with the background value. Thus, the collection interval for background concentration samples should be increased to avoid interference from other ships’ emissions. According to the relevant references [

7,

25,

28], the background concentration of SO

2 is the average over the 30 min preceding the peak concentration in this study, because sulfur dioxide concentrations do not fluctuate significantly when no ships are passing by.

4.2. Case Analysis for Concentration Matching of Ship Emission

To verify the feasibility and accuracy of the ship matching method in practical applications, this study randomly selected three effective matching cases (including a frequent peaks scenario and a sparse but conspicuous peaks scenario) of ships with excessive emissions from the monitoring area of the Nanjing Dashengguan Yangtze River Bridge:

- (1)

Case analysis of monitoring data on 5 April 2022 (Frequent Peaks Scenario)

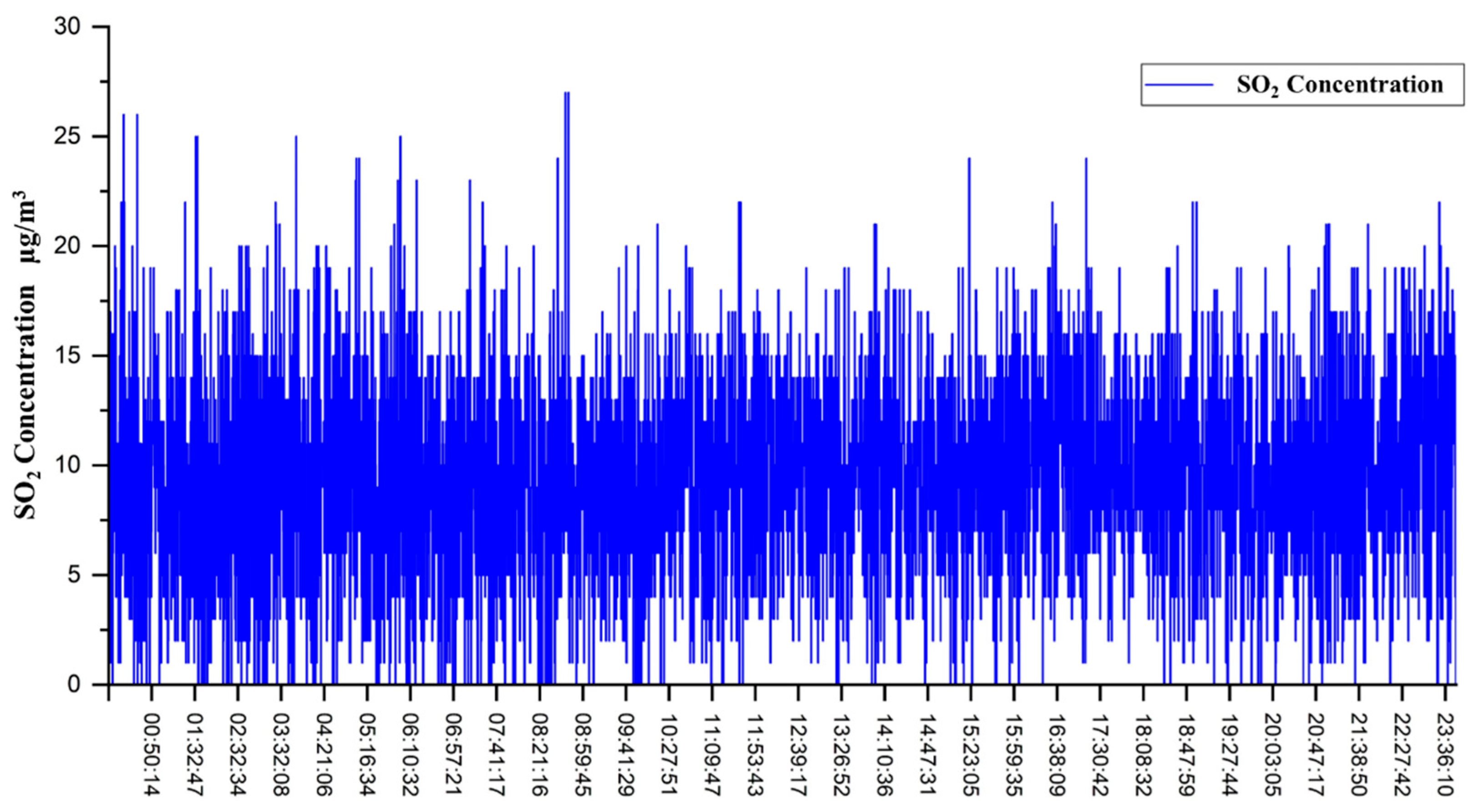

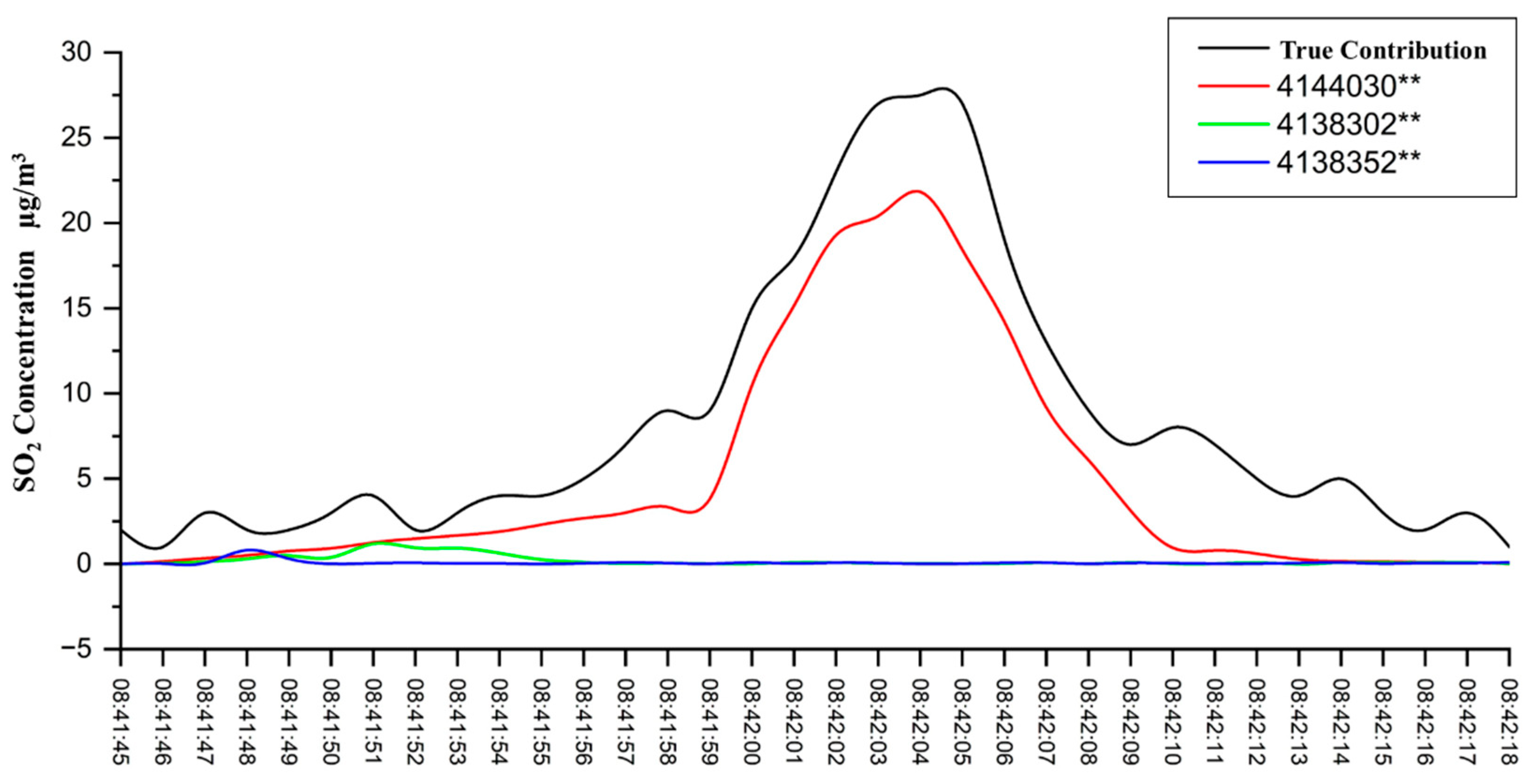

Figure 5 shows the variation in monitored SO

2 concentration on 5 April 2022. The data indicate significant fluctuations in SO

2 concentration throughout the day, with most values ranging between 5 and 25

, accompanied by frequent peaks. These peaks are likely related to frequent ship passages. Combining monitored concentration information and AIS information, a specific peak concentration time window was randomly selected for matching: 08:41:45 to 08:42:18. Three ships passed during this period.

Table 4 lists the type, speed, and operating conditions of these three ships (for privacy, the last two digits of the MMSI for each ship are replaced with “**”).

Based on the proposed ship monitoring concentration matching method for multi-ship scenarios, the diffusion concentration sequences for these three ships were calculated as comparison sequences. The true contribution concentration sequence of the ship exhaust was used as the reference sequence. The relational grade between each ship and the reference sequence was calculated, and the matching probability for the three ships was further determined through interpolation. The results are shown in

Table 5.

Figure 6 shows the calculated concentration curves of the three ships and the true contribution concentration curve. For the ship with MMSI 4144030**, the calculated curve shows a consistent trend with the true contribution concentration curve, and the matching probability calculated using grey relational analysis is 88.40%. The low similarity between the calculated concentration curves of the other two ships and the true contribution concentration is corroborated by their low matching probabilities. Fuel sulfur content testing was conducted on this ship, resulting in 0.349%, confirming excessive sulfur content (greater than the limit of 0.1%).

- (2)

Case Analysis of Monitoring Data on 5 August 2022 (Sparse but Conspicuous Peaks Scenario)

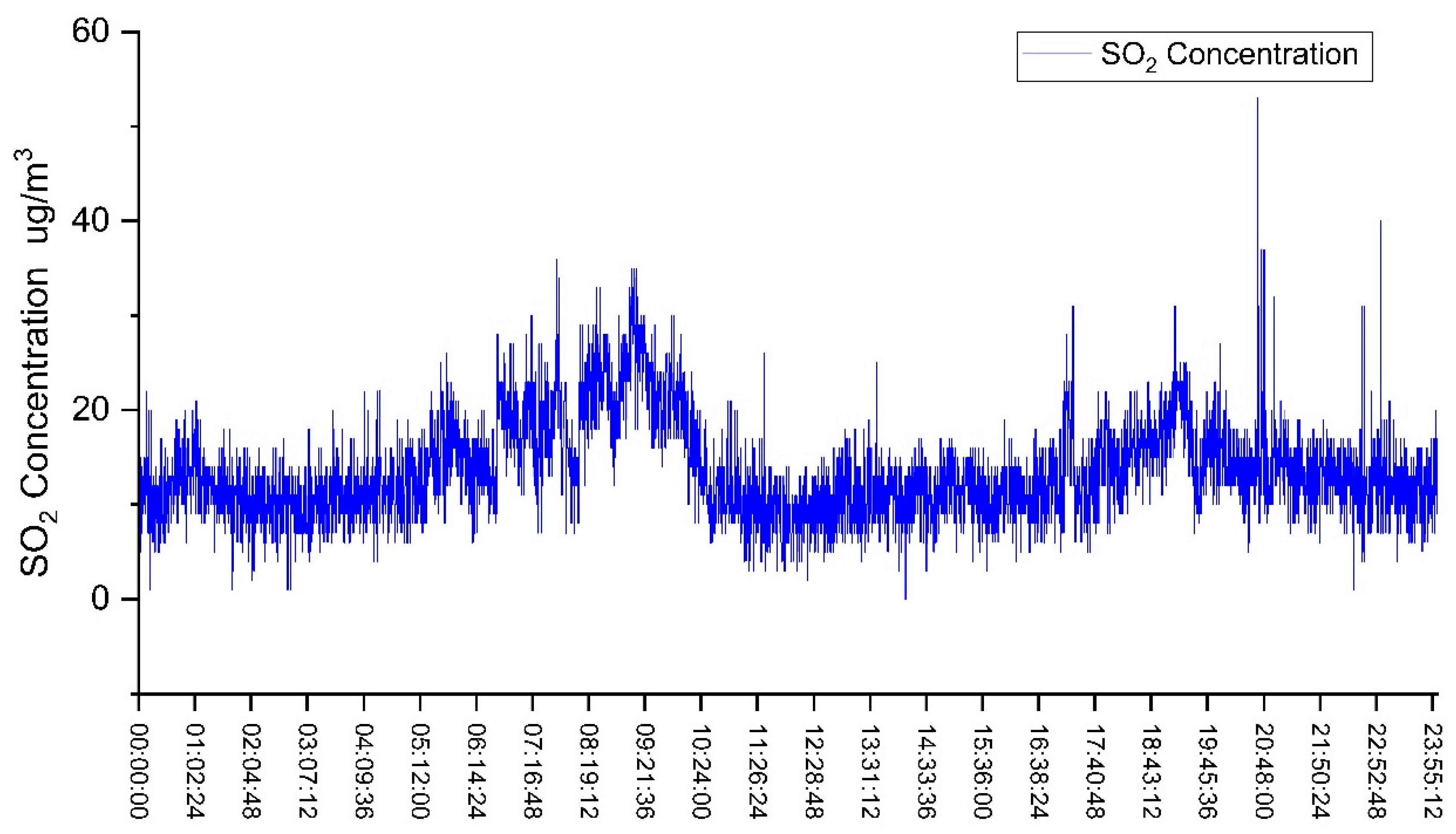

Figure 7 shows the variation in monitored SO

2 concentration on 5 August 2022. It can be observed that the monitored SO

2 concentration trend is relatively stable, mainly within the range of 10–20

. Combining monitored concentration and AIS data, two periods with excessive concentrations were identified: 20:45:43–20:46:45 and 22:57:22–22:58:14. Ship matching was performed for these two periods.

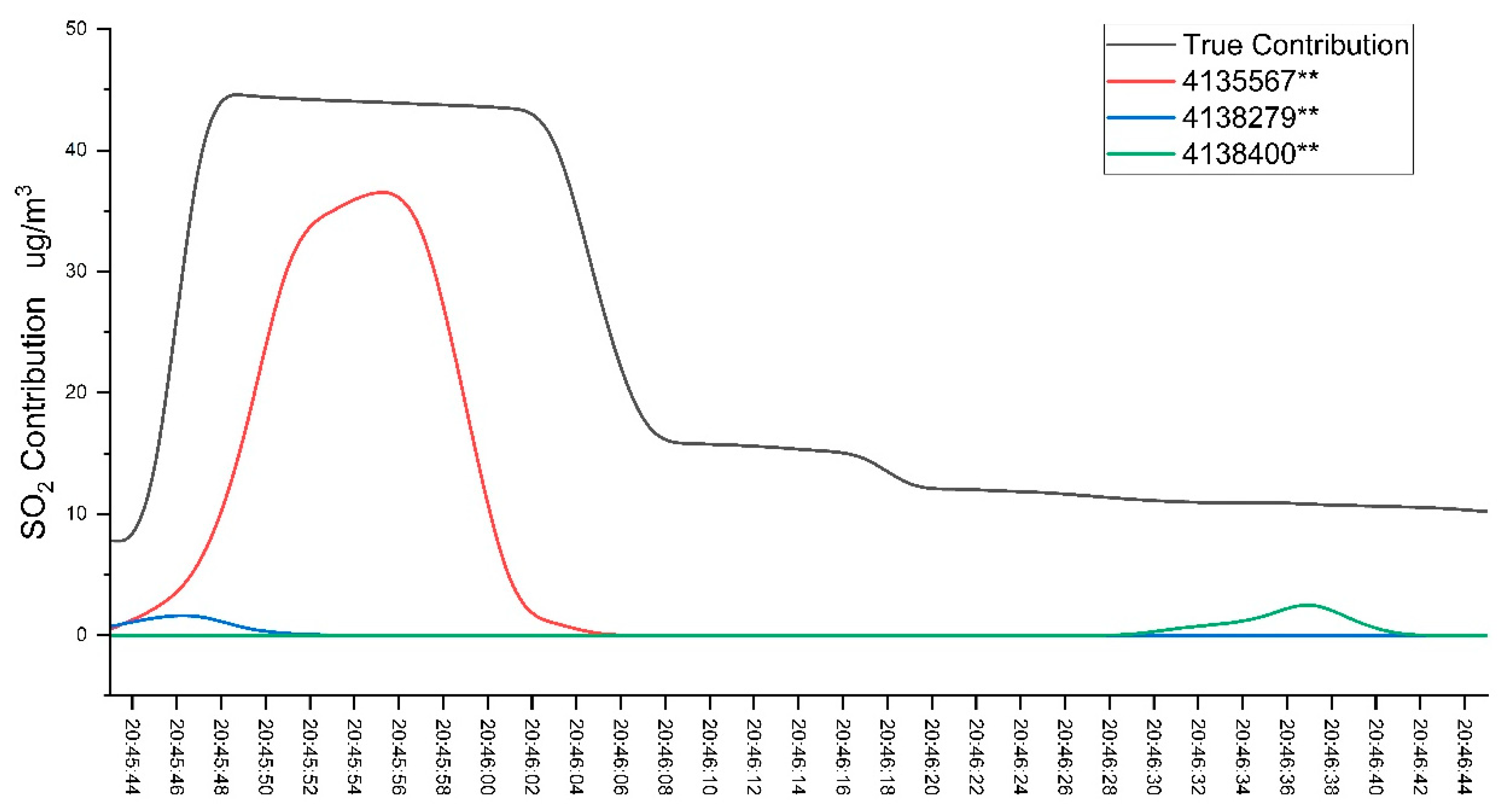

The matching results for the ship with excessive emissions during the period 20:45:43–20:46:45 are shown in

Table 6. The results indicate that the matching probability for the ship with MMSI 4135567** is significantly higher than that of the other two ships. The calculated concentration curves of the three ships and the true contribution concentration curve also confirm these results. As shown in

Figure 8, the calculated concentration curve for the ship with MMSI 4135567** exhibits a consistent trend with the true contribution concentration curve, and the matching probability calculated using grey relational analysis is 85.45%. Fuel sampling and testing by maritime authority staff confirmed a sulfur content of 0.645%, verifying excessive sulfur content (greater than the limit of 0.1%).

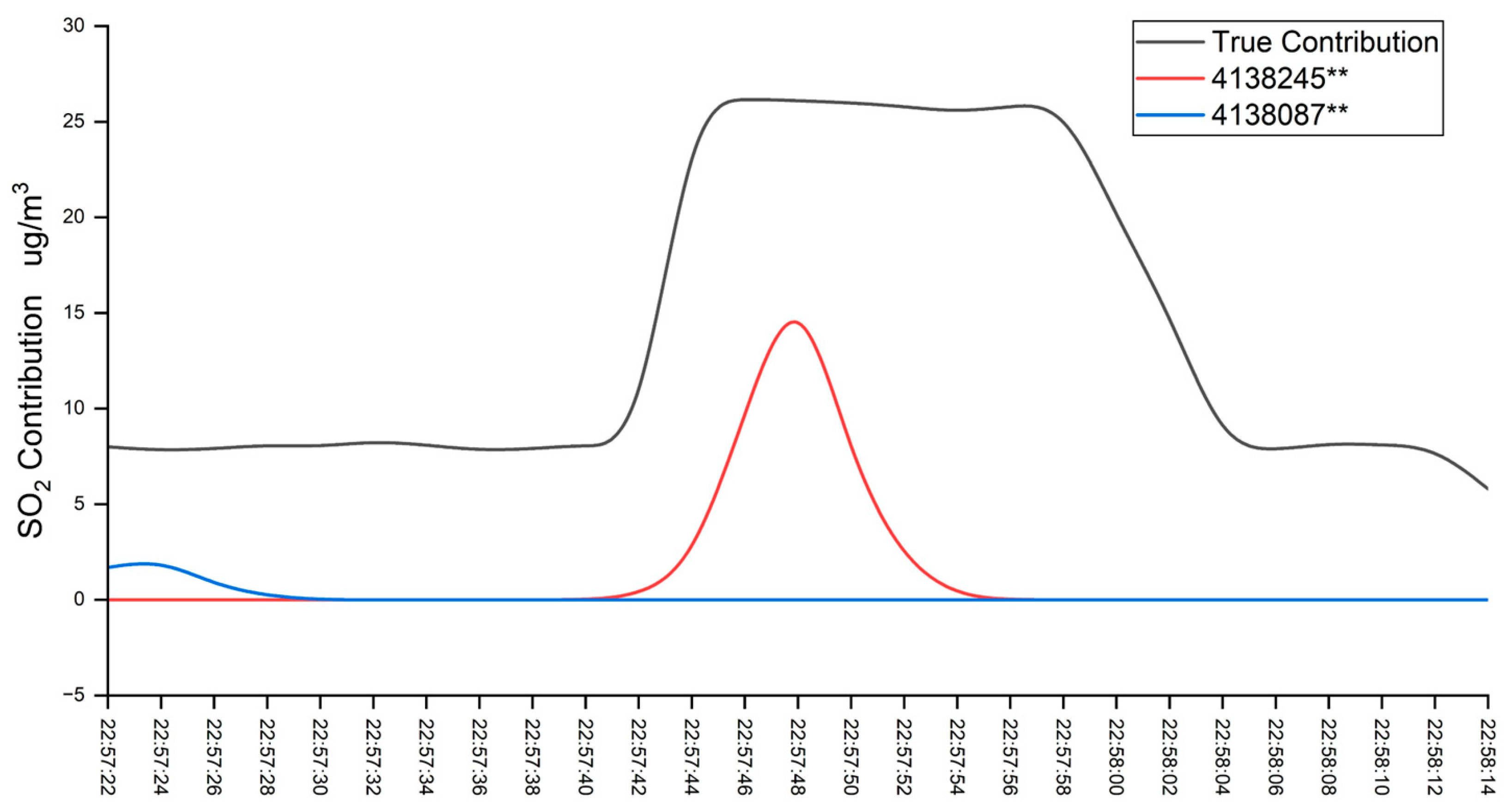

The matching results for the ship with excessive emissions during the period 22:57:22–22:58:14 are shown in

Table 7. The results show that two ships were matched during this period. The matching probability for the ship with MMSI 4138245** is 82.02%, which is much higher than that of the other ship. In

Figure 9, compared to the other ship, the calculated concentration curve for the ship with MMSI 4138245** shows a consistent trend with the true contribution concentration curve, aligning with the results from the grey relational analysis. Fuel sulfur content testing for this ship showed 0.571%, confirming excessive sulfur content (above the limit of 0.1%).

4.3. Sulfur Content Assessment for Exemption Ships

In ship fuel sulfur content monitoring, obtaining real-world data requires onboard sampling and laboratory analysis. This process is not only time-consuming and labor-intensive but is also constrained by ship operation schedules and enforcement conditions. These challenges make it difficult to validate large-scale estimates of ship fuel sulfur content directly. Therefore, this study utilizes a dataset comprising 97 exempted ships to validate the effectiveness of the proposed matching methodology. Exempted ships are those whose fuel exceeds the sulfur content standard but have been pre-reported to the maritime authorities and granted the necessary passage permits. Since the fuel sulfur content of exempted ships is known to exceed the standard, the number of ships identified with excessive sulfur content (>0.1%) through the calculations can be used to verify the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed method.

Analysis of AIS data from 97 ships during their passage past the monitoring point revealed that 32 ships (approximately 33%) encountered scenarios in which multiple ships navigated simultaneously within the detection range. This prevalent occurrence further substantiates the inadequacy of the traditional single-source assumption in real-world monitoring environments. Conventional methods neglecting this multi-source superposition effect are consequently prone to miscalculation of sulfur content in ship fuel.

As presented in

Table 8, among the 32 multi-ship scenarios, the proposed method calculated sulfur content exceeding the 0.1% threshold for 27 ships, achieving an evaluation accuracy of 84.38%. In contrast, conventional approaches typically exclude such complex multi-ship scenarios from sulfur content assessment to avoid potential inaccuracies. Furthermore, within the total set of 97 exempted ships, 85 were identified as exceeding sulfur content standards, yielding an overall accuracy of 87.63% for the sulfur content evaluation methodology. These results demonstrate that despite the challenges posed by multi-source superposition effects, the matching method successfully identifies non-compliant ships, confirming its superior performance in complex operational environments.

4.4. Uncertainty Analysis for Matching Results

In this study, variability in emission factors is a significant factor influencing the accuracy of SO2 emission estimates. The factors such as ship type, fuel quality, and operational conditions introduce inherent variability. Collectively, these factors mean that a single emission factor cannot fully reflect real-world conditions. However, in practice, the differences in ship emission factors are generally limited, primarily due to the convergence of industry standards, the relative stability of marine fuel quality, and the constrained range of operational profiles. These factors collectively limit the amplitude of emission factor variation across conditions, typically confining fluctuations to 10% to 30%, with no considerable deviations observed even under extreme scenarios. The magnitude of this variation is insufficient to affect the final analytical outcomes significantly. Consequently, the use of average or typical values reasonably reflects overall trends while avoiding undue model complexity and computational burden.

Errors in AIS data typically manifest as missing values or anomalies. Without proper preprocessing, these errors can lead to calculated results that deviate significantly from actual values. For instance, in Case 2, the ship (MMSI 4135567**) exhibited abnormal latitude and longitude data in its AIS records. Had these raw data been used without correction and repair, substantial deviations would have occurred in the forward-calculated emission concentration curve for this ship. As illustrated in the matching diagram comparing the calculated concentrations of the three ships against the true contribution concentration, the uncorrected AIS data resulted in significant errors in both the matching probability and the calculated sulfur content (as shown in

Table 9 and

Figure 10). The proposed method incorporates comprehensive AIS data preprocessing and repair procedures, effectively preventing such inaccuracies from occurring (as shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 8).