Modelling the Longevity of Beach Nourishment and the Influence of a Detached Breakwater

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framework and Objectives

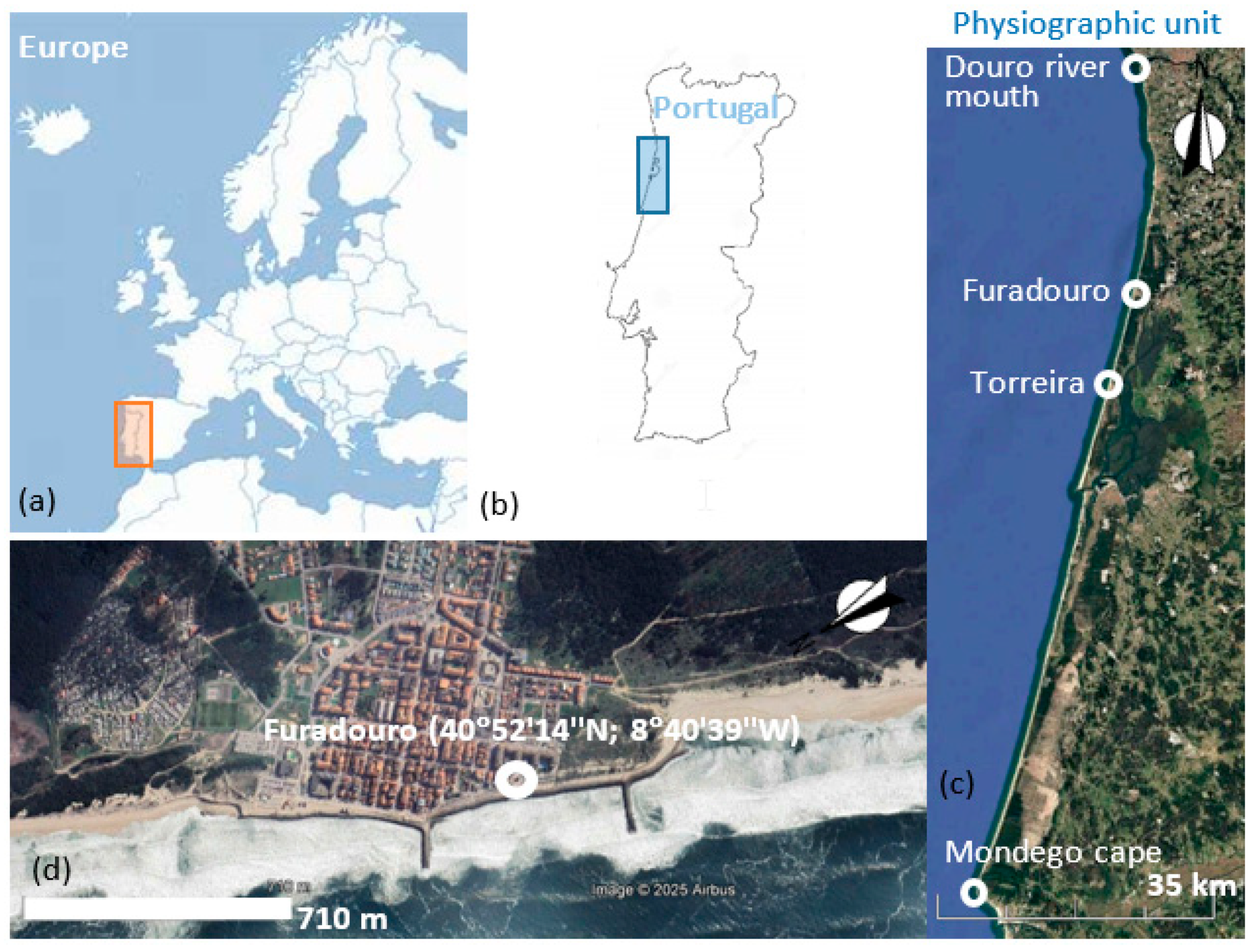

1.2. Study Site

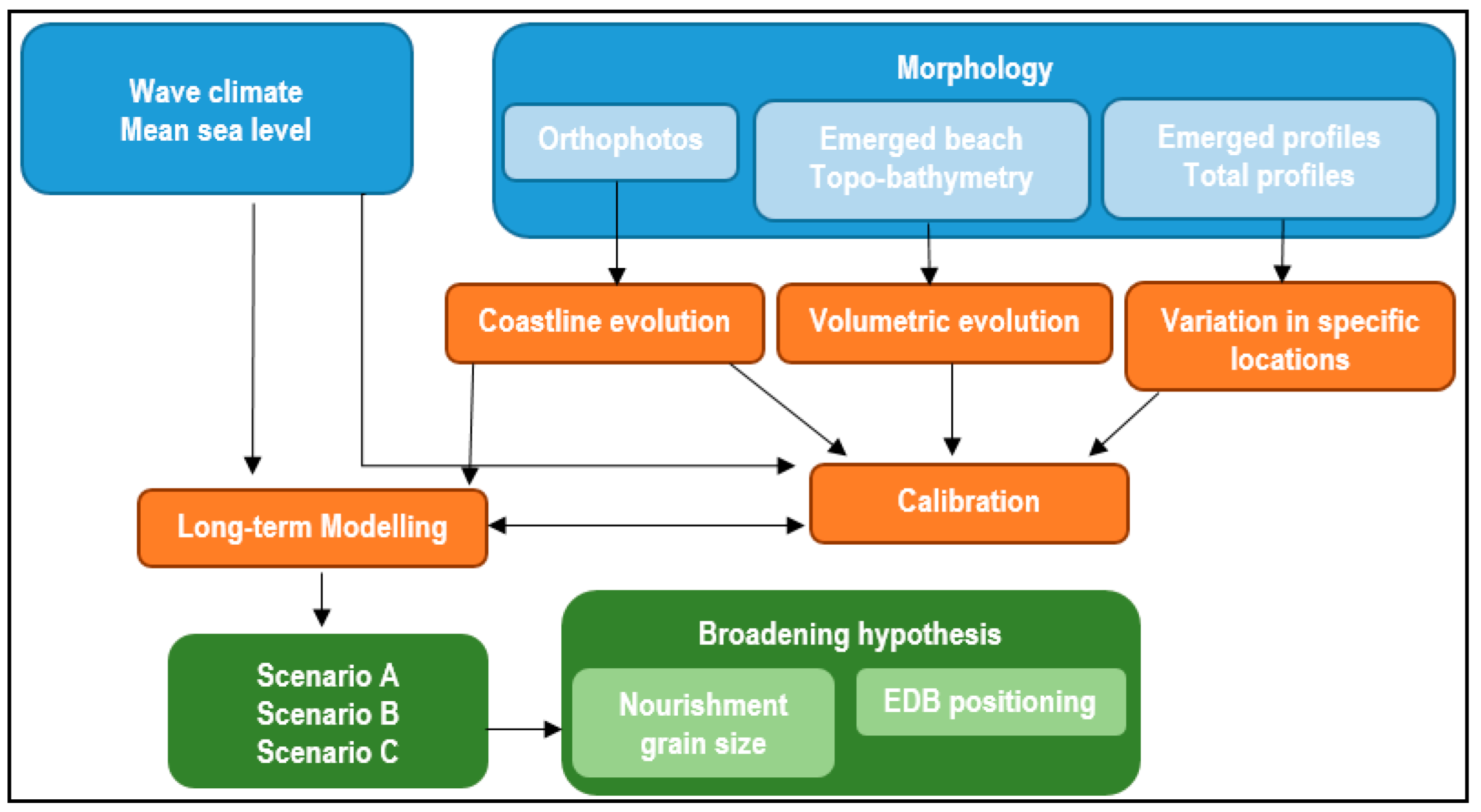

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Morphological Evolution Analysis

- (i)

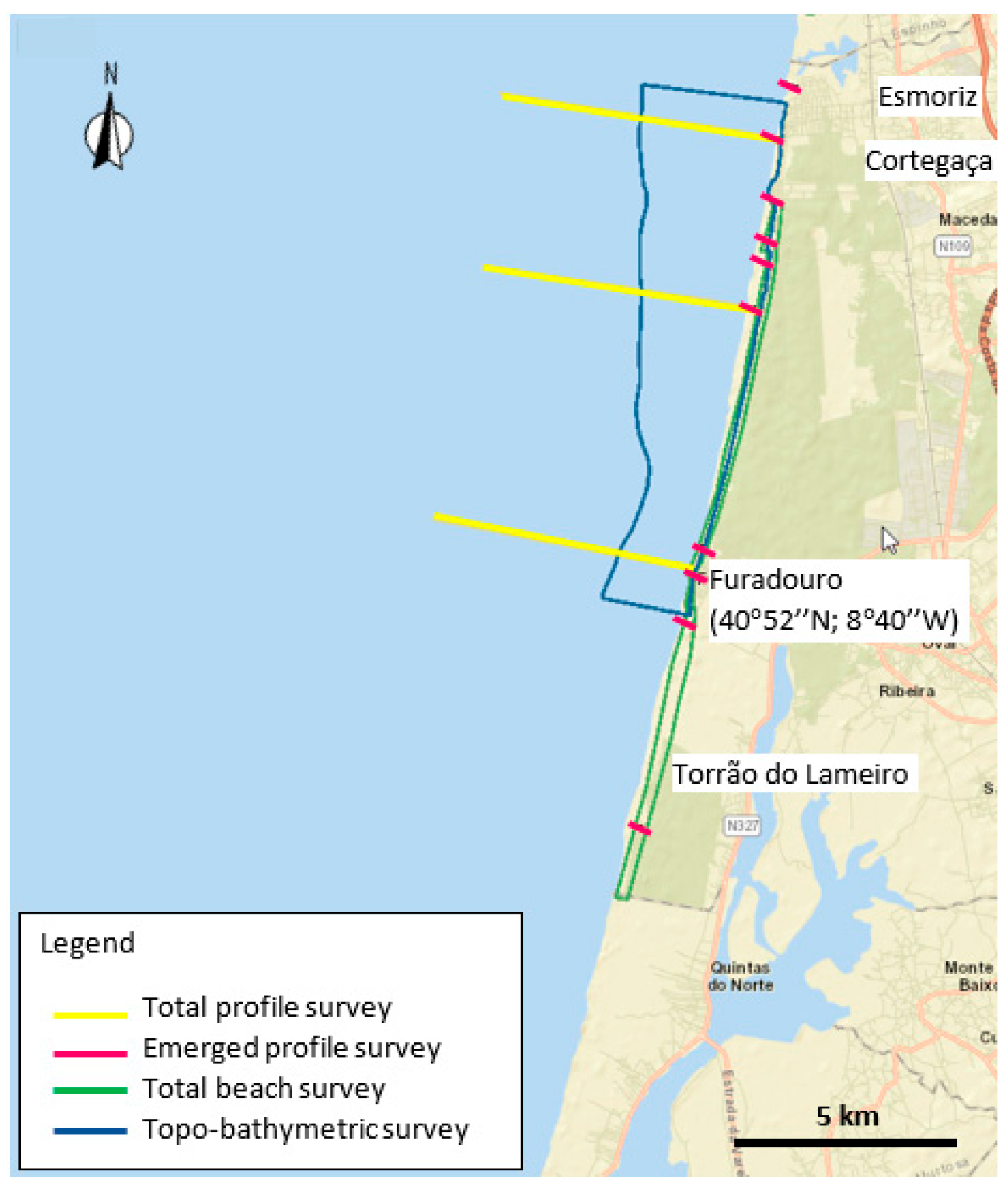

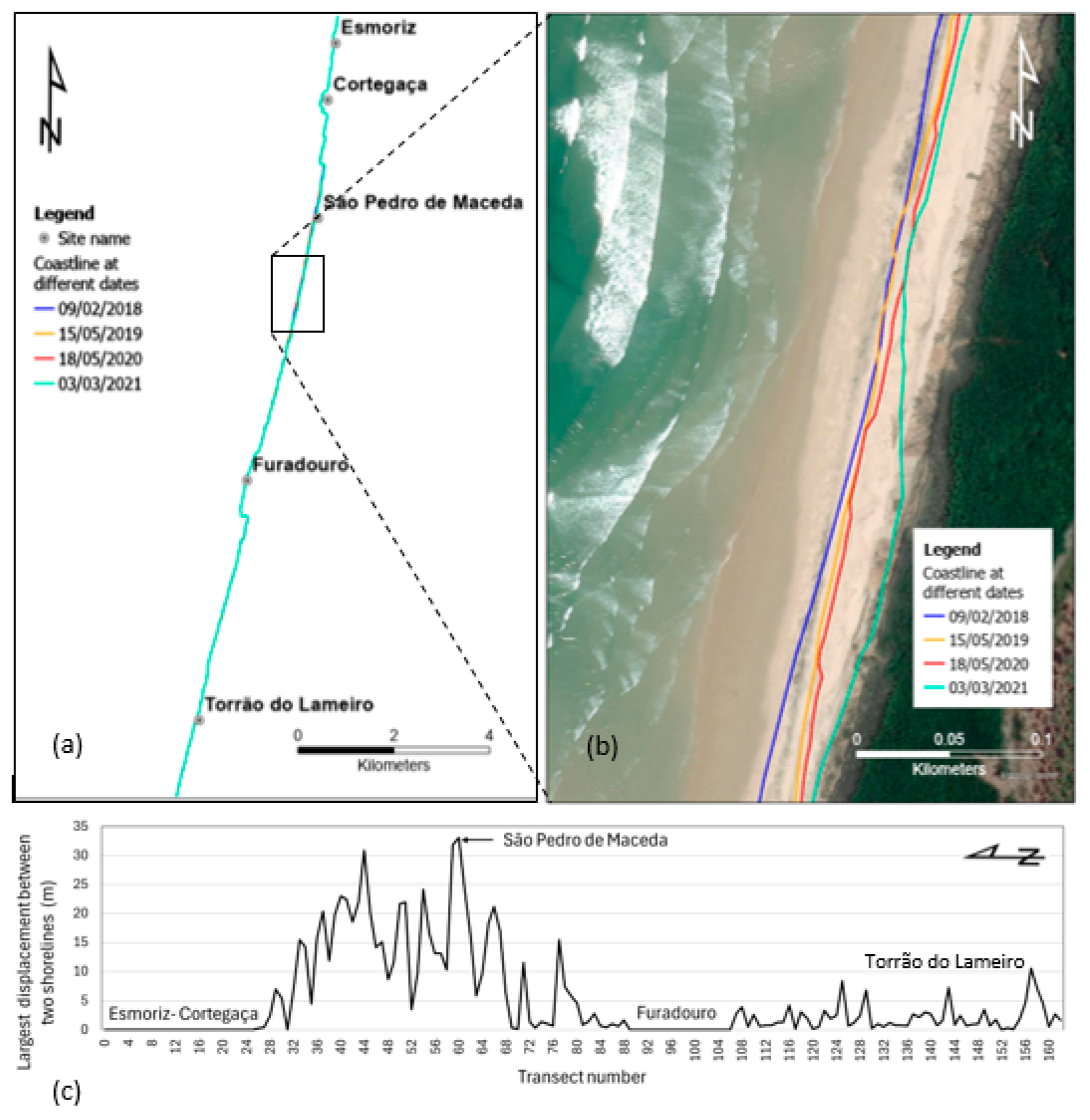

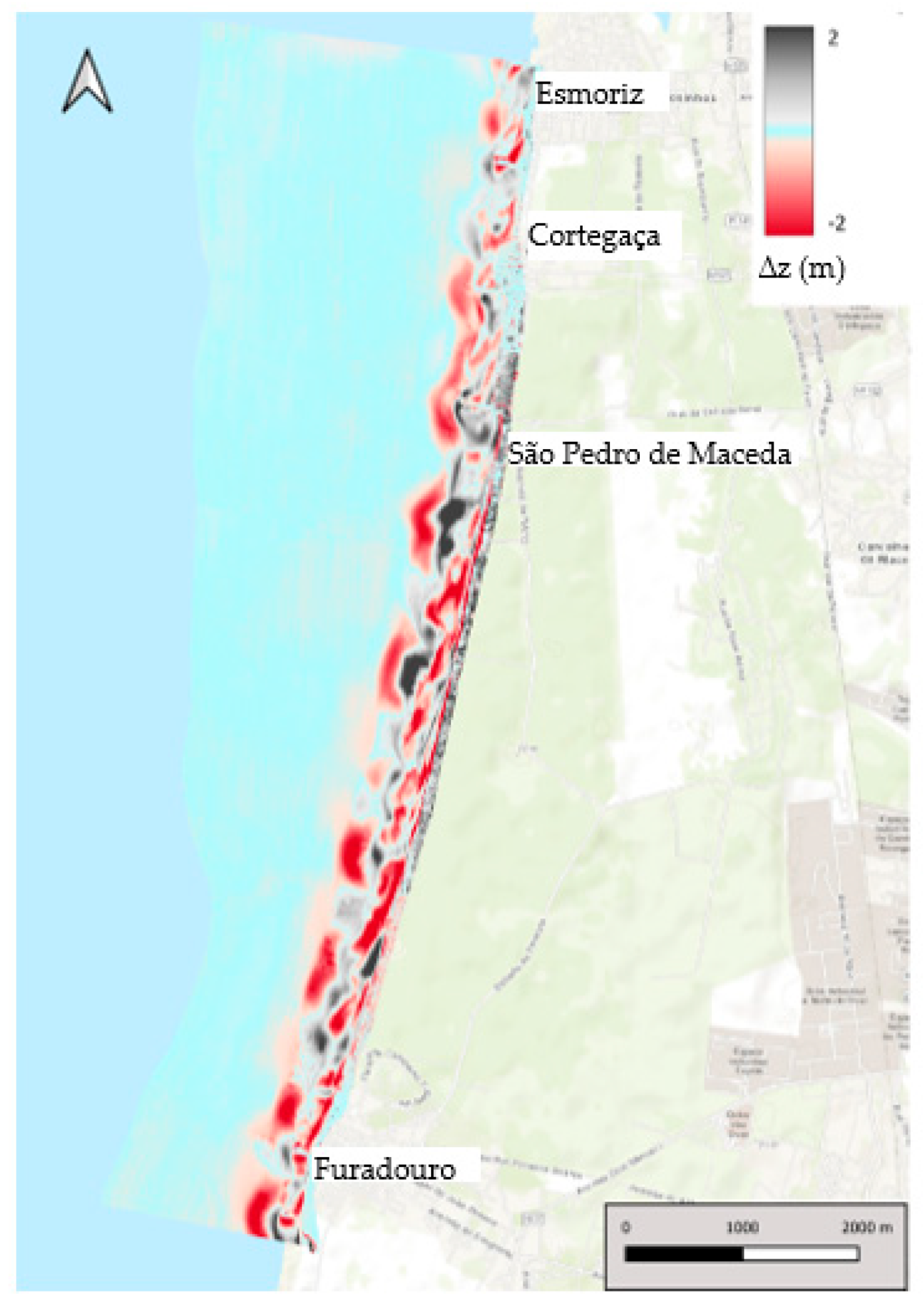

- The total beach surveys consisted of acquiring terrain surface data on emerged beaches (from the −1 m ALTH38, where ALTH38 is the vertical datum, where zero refers to the approximate mean sea level) and dunes using airborne methods through aerial photogrammetry. The frequency of execution was annual, resulting in 5 surveys (Table 1). The surveys’ areas had an alongshore length of 14 km (Figure 3).

- (ii)

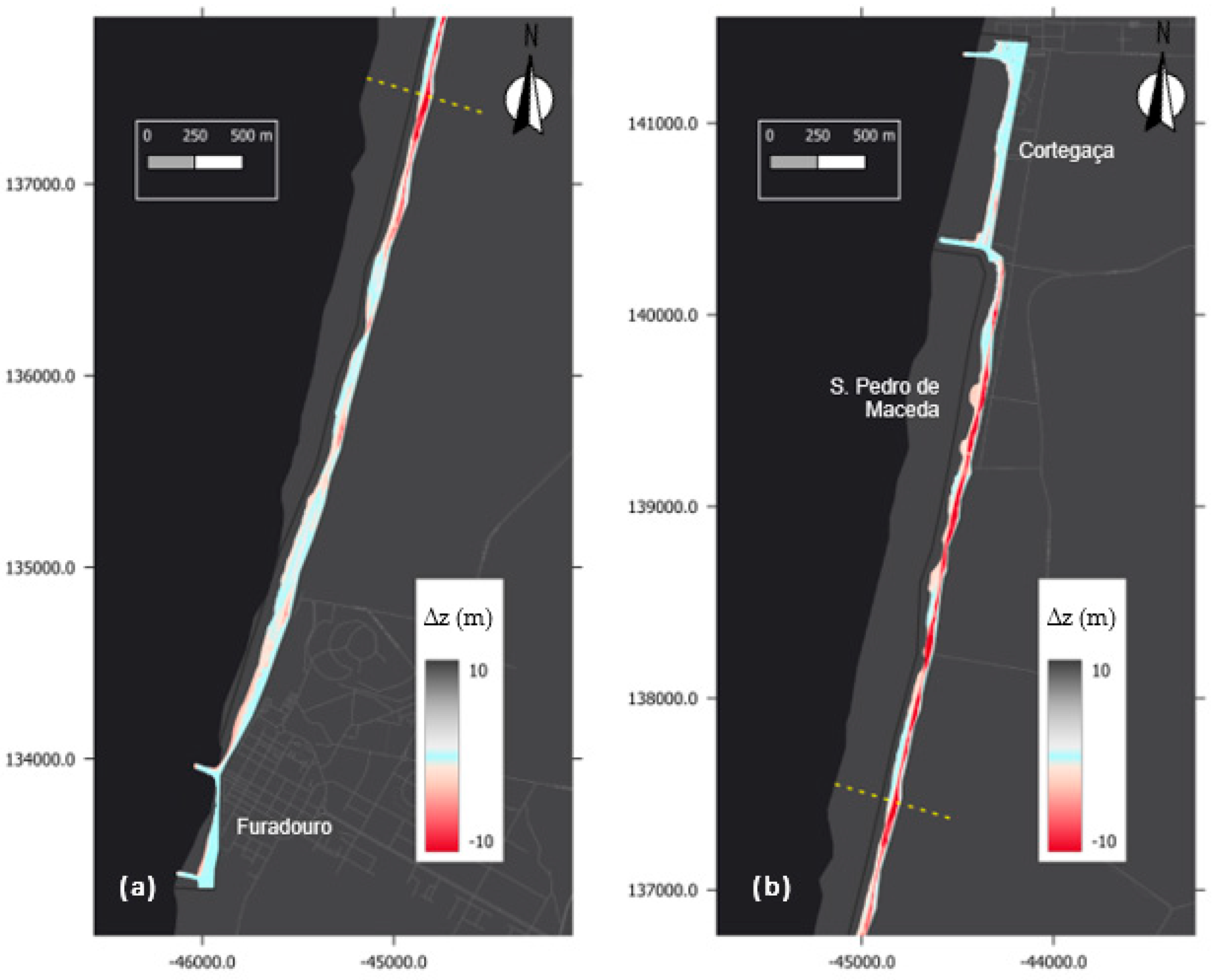

- The topobathymetric surveys consisted of the combination of the surveys of the emerged and submerged beach, creating a single surface, which ensured continuity and seamless connection between these two domains. The bathymetric surveys were carried out using a specific multi-beam echosounder, providing full coverage from the −14 m ALTH38 to the −5 m ALTH38. A single-beam echosounder was used in areas closer to the shore (from the −5 m ALTH38 to the −3 m ALTH38). The horizontal resolution of the surveys was 0.3 m. The largest vertical uncertainty associated with these data is approximately 0.05 m, and the digital elevation models (DEMs) derived from the complete surveys have a 0.1 m spatial resolution. The frequency of execution was annual, resulting in 3 surveys (Table 1). The surveys’ areas had an alongshore length of 10 km (Figure 3).

- (iii)

- The total profile surveys consisted of integrating an emerged beach and submerged profile, yielding a unique topobathymetric profile, starting from a fixed point on land (beyond the high beach) and extending to the sea (−14 m ALTH38). These surveys were carried out using GPS/RTK on land and a single-beam echosounder at sea. The frequency of execution was semiannual, resulting in 5 surveys (Table 1). The study site includes 3 total profiles (Figure 3).

- (iv)

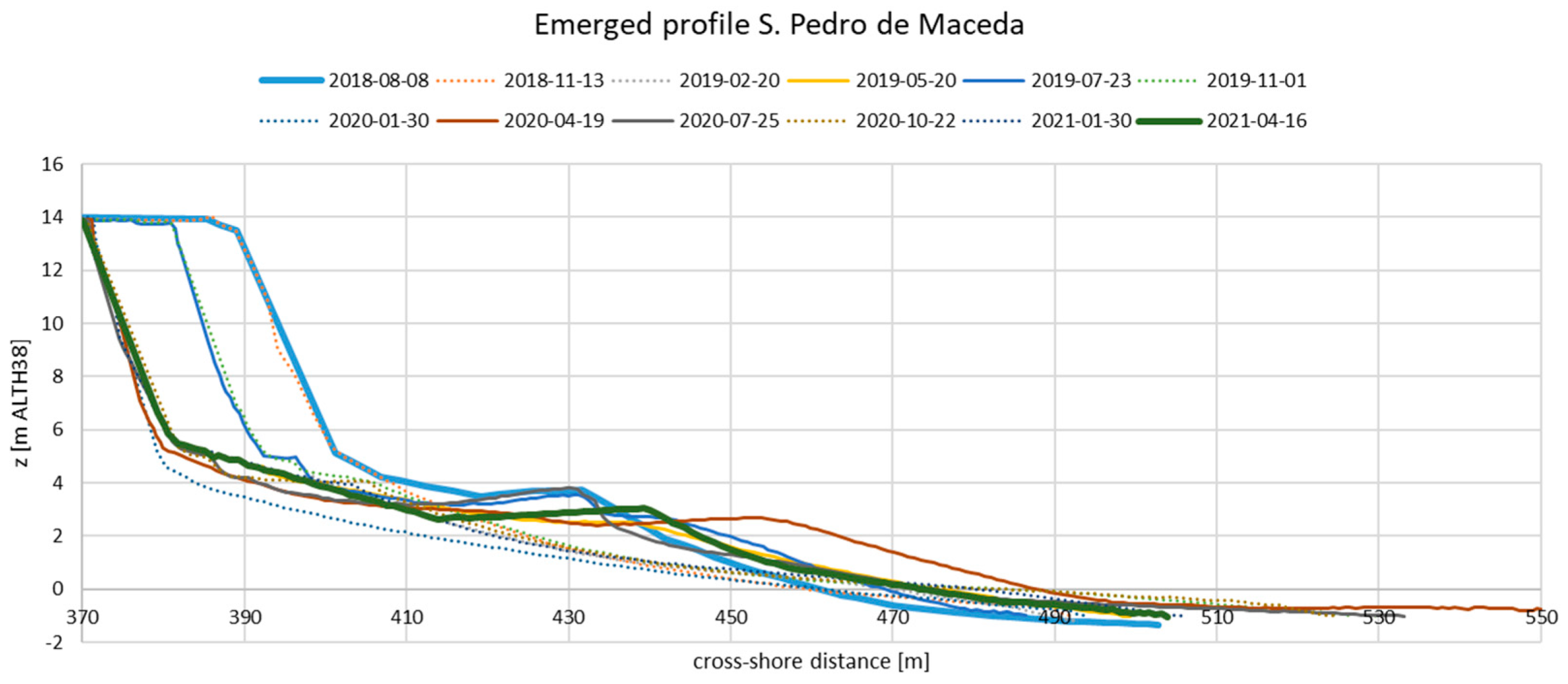

- The emerged profile surveys consisted of acquiring a cross-shore profile of the aerial beach, originating from a fixed point on land (beyond the high beach) and ending at sea (low-tide limit). The surveys were carried out using GPS/RTK. The frequency of execution was quarterly, resulting in 12 surveys (Table 1). The study site includes 5 emerged profiles (Figure 3).

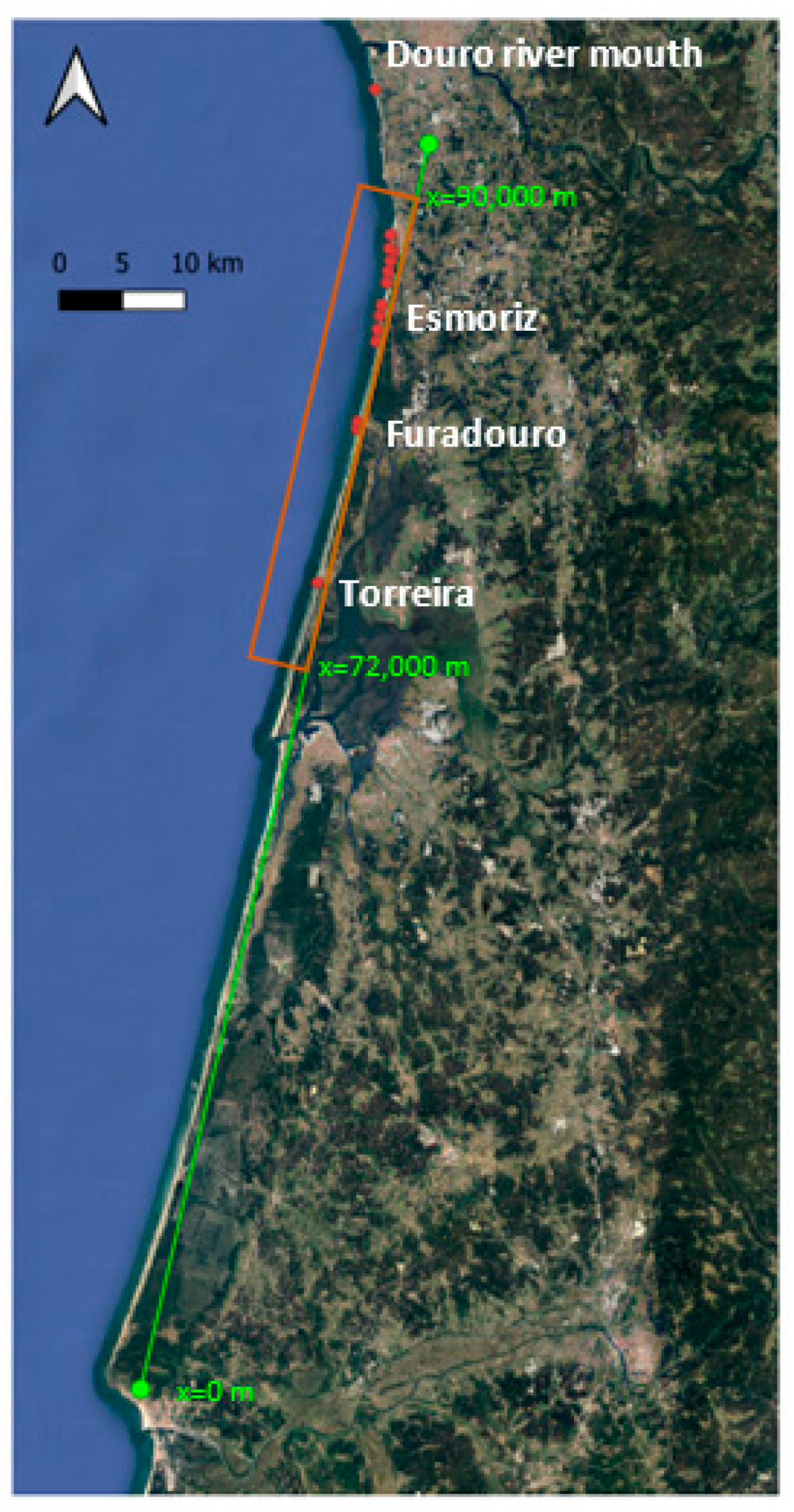

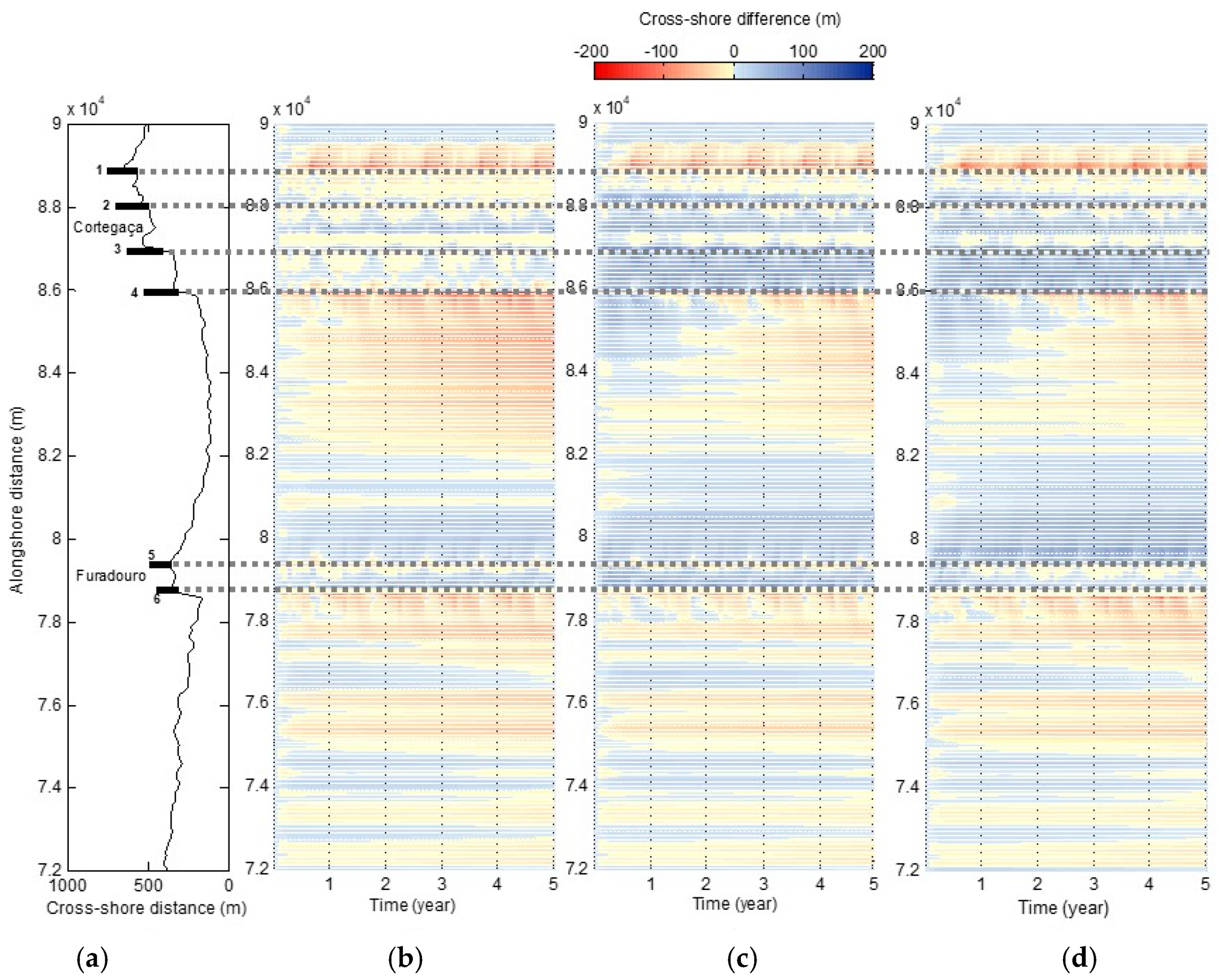

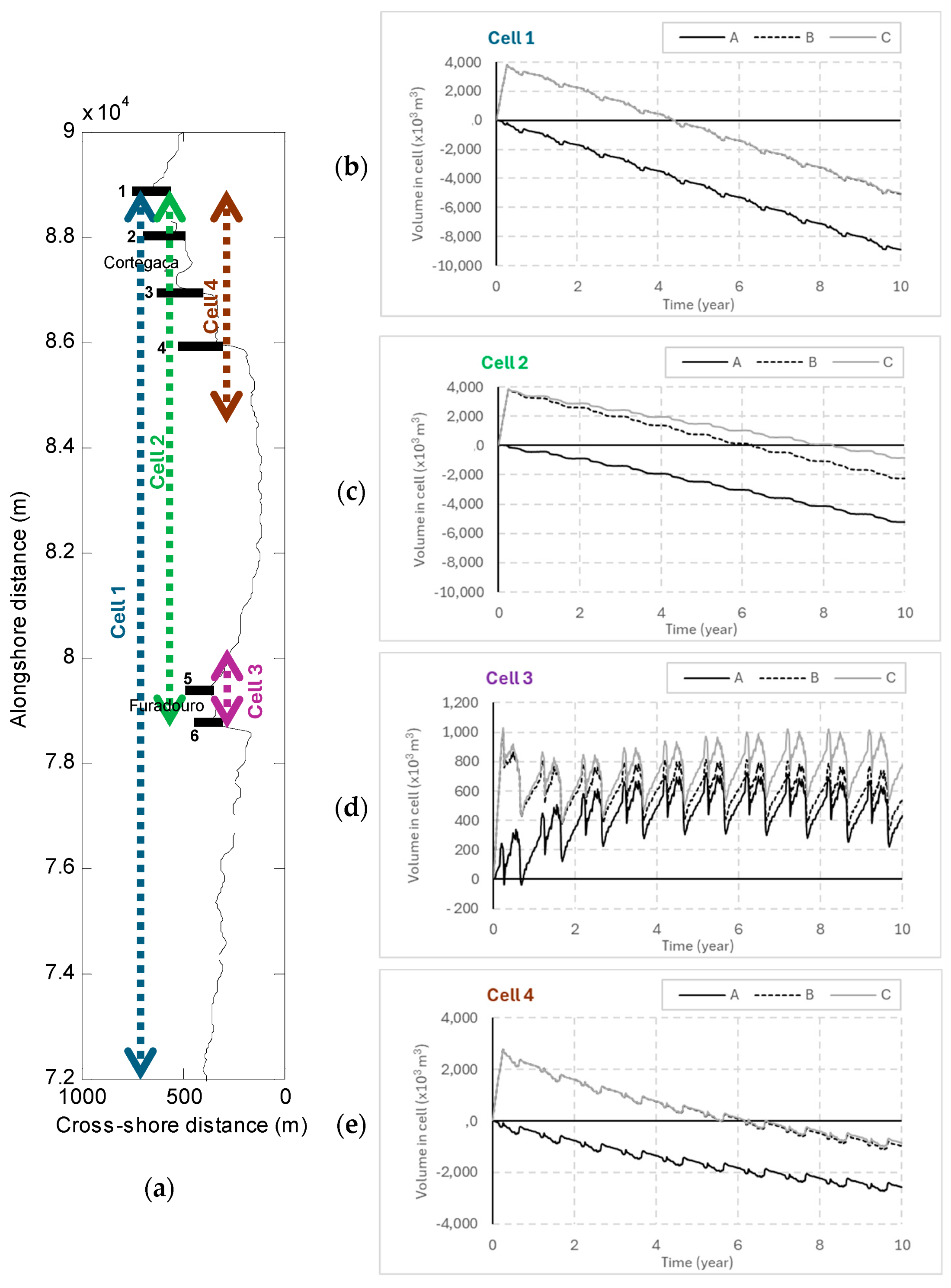

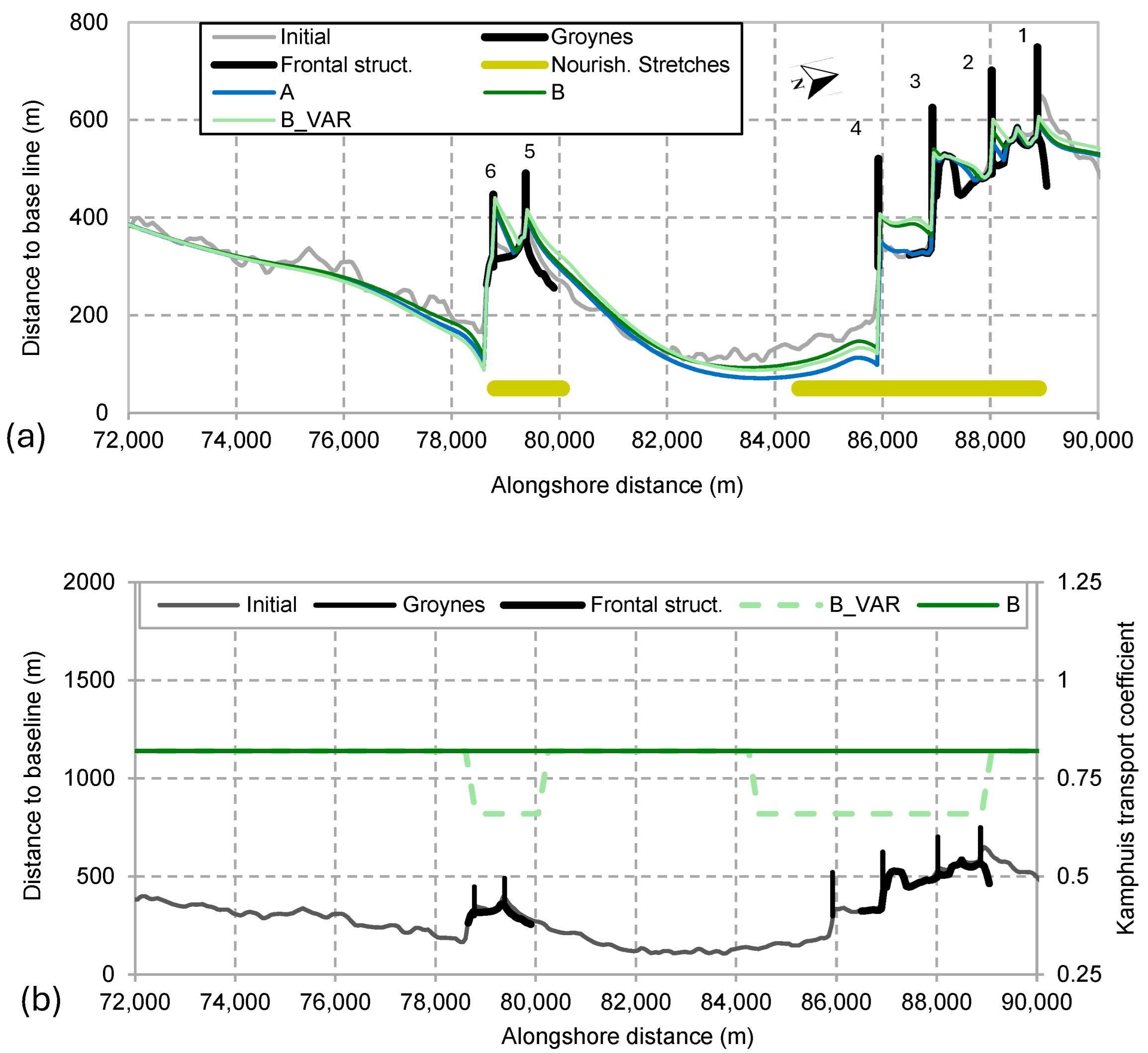

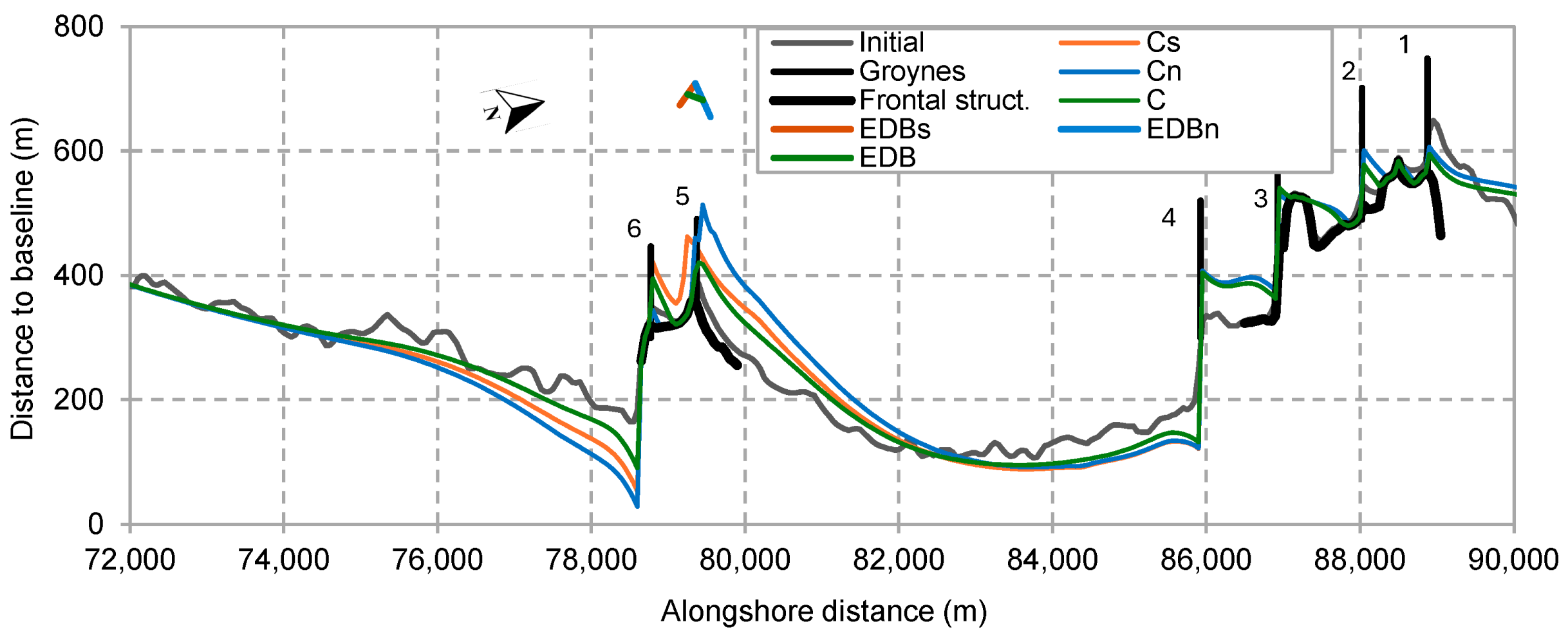

2.2. Intervention Scenarios

- A.

- The absence of nourishment or any other type of intervention, i.e., the “do nothing” scenario.

- B.

- A one-shot 4 × 106 m3 sand nourishment intervention, divided into three locations:

- B1.

- A 1 × 106 m3 shoreface nourishment (submerged), between the topobathymetric isolines −6 m ALTH38 and −10 m ALTH38, along a 2000 m stretch, between 1500 m north of the Maceda groyne and 500 m south of the Maceda groyne (Figure 4);

- B2.

- A 2 × 106 m3 beach nourishment (emerged) along two stretches: 0.9 × 106 m3 in the 2950 m long stretch, between the north groyne of Esmoriz and the groyne of Maceda (B2a), and 1.1 × 106 m3 in the 1500 m long stretch south of the Maceda groyne (B2b) (Figure 4);

- B3.

- A 1 × 106 m3 beach nourishment (emerged) along a 1250 m stretch, between the cross-shore section 700 m north of the North Furadouro groyne and the South Furadouro groyne (Figure 4).

- C.

- The combination of the previous scenario, B—i.e., the nourishment interventions—with a single EDB located in front of the northern groyne of Furadouro (Figure 4).

2.3. Numerical Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Recent Morphological Evolution

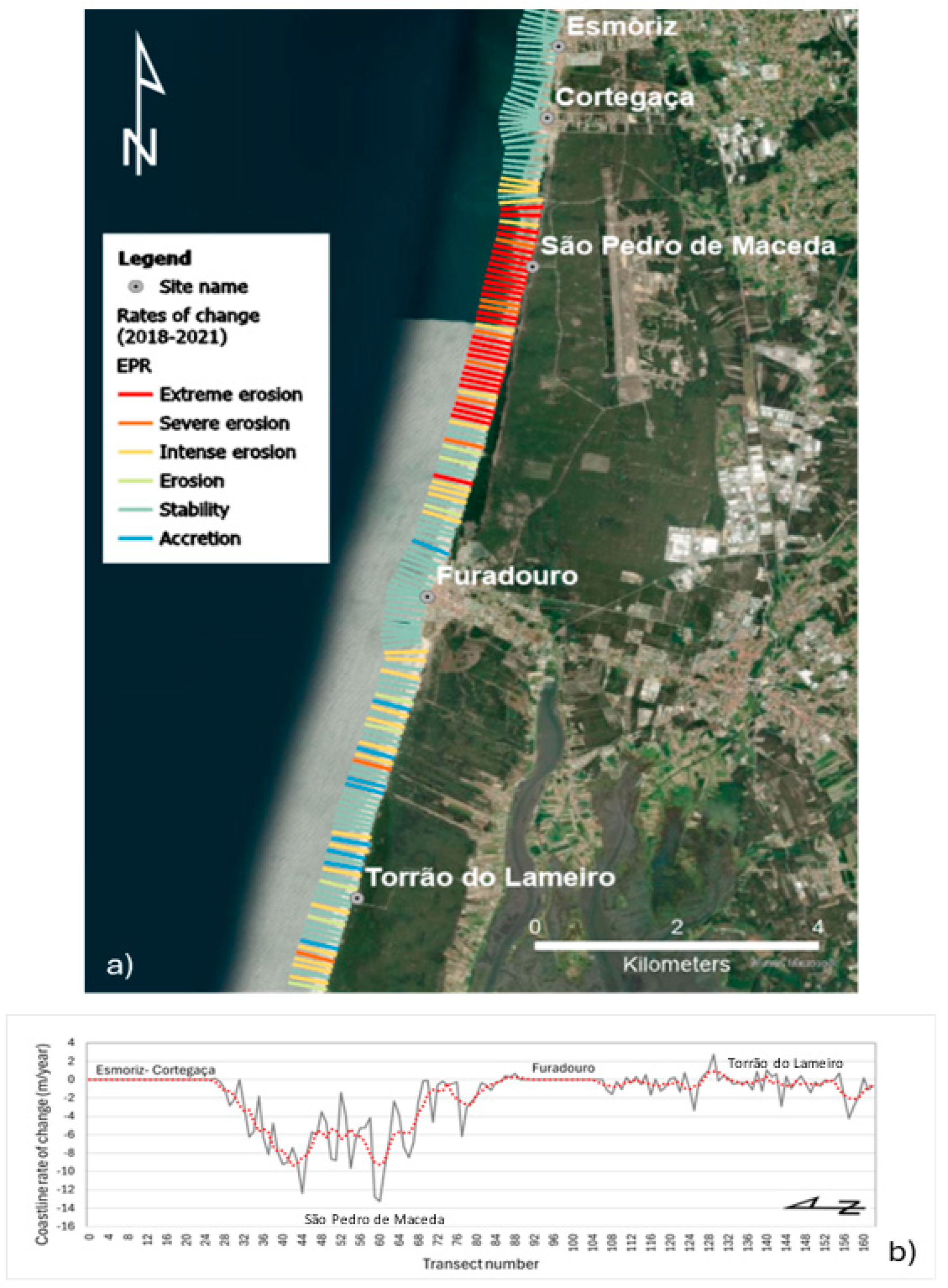

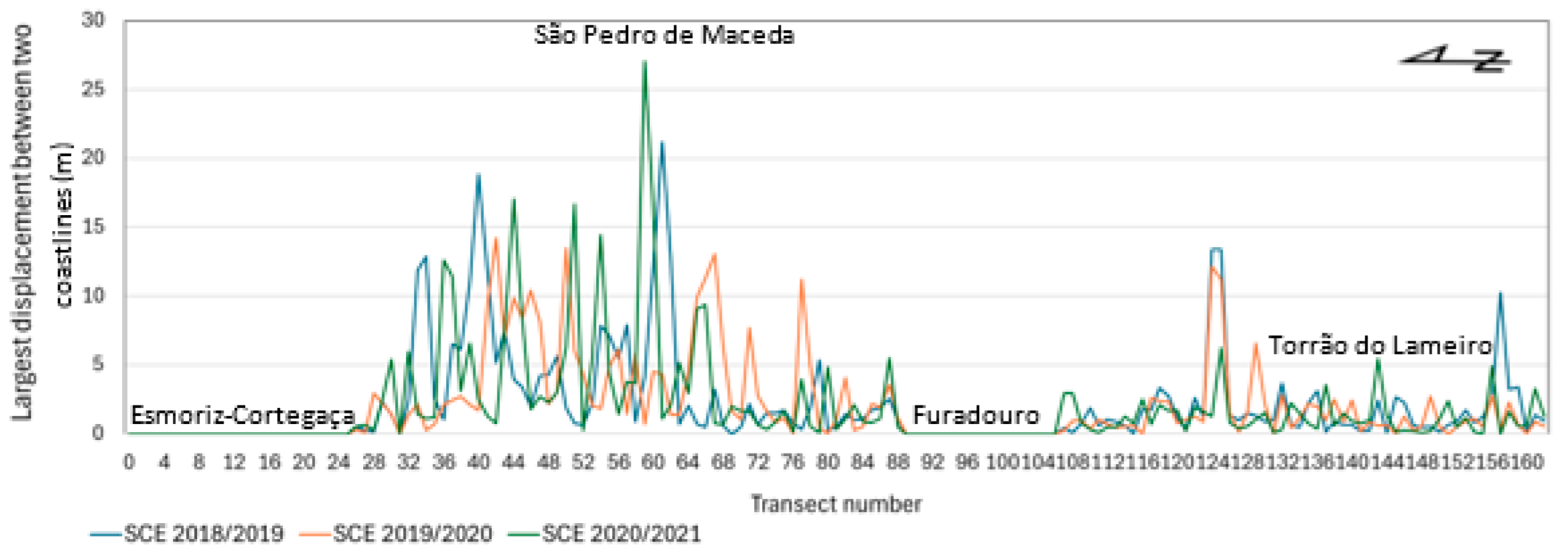

3.1.1. Coastline Evolution

3.1.2. Volumetric Evolution

3.2. Coastline Evolution Under Intervention Scenarios

3.3. Retained Nourishment Volume Under Intervention Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The most pronounced erosional impact was recorded in the area north of Furadouro, which was formally classified as extreme erosion. The maximum volume loss of sediment occurred on the emerged beach face, although substantial volumetric changes were also observed across the nearshore and upper shoreface, extending down to the depth of closure.

- The implemented nourishment’s longevity is approximately 7.5 years within the intervention area. However, considering a larger affected stretch in the direction of the littoral drift, this longevity reduces to 4.5 years due to sediment redistribution.

- Introducing an emerged detached breakwater alongside the nourishment yielded notable increases in beach width north of Furadouro but also aggravated sediment loss to the south. Despite varying the breakwater positions, the cumulative sediment balance over a decade for the combined approach was comparable to that with nourishment alone, and no tombolo or pronounced salient was developed.

- Overall, the breakwater’s impact is local and it does not significantly alter the broader pattern of erosion or accretion established by nourishment alone. Its principal advantage is providing more persistent local benefits compared to periodic nourishment, but further consideration of environmental impacts, cost-effectiveness, long-term maintenance, and operational feasibility is required.

- Importantly, the study revealed that the nourishment lifespan is strongly influenced by the grain size of borrowed sediments; coarser sand may reduce longshore sediment transport and modify profile stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Schipper, M.A.; Ludka, B.C.; Raubenheimer, B.; Luijendijk, A.P.; Schlacher, T.A. Beach nourishment has complex implications for the future of sandy shores. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 2, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsupavanich, C.; Pranzini, E.; Ariffin, E.H.; Yun, L.S. Jeopardizing the environment with beach nourishment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudt, F.; Gijsman, R.; Ganal, C.; Mielck, F.; Wolbring, J.; Hass, H.C.; Goseberg, N.; Schüttrumpf, H.; Schlurmann, T.; Schimmels, S. The sustainability of beach nourishments: A review of nourishment and environmental monitoring practice. J. Coast. Conserv. 2021, 25, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, K. Relationship Analysis Between Beach Nourishment Longevity and Design Aspects. A Study of the Central Holland Coast Using a Multiple Linear Regression. Master’s Thesis, Delft UniversityofTechnology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. Available online: https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:7991a9b8-c6f6-41d4-a8c2-dac71c3a685d (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Krafft, D.R.; McFall, B.C.; Melby, J.A.; Johnson, B.D. Lifecycle analyses of subaerial beach nourishments with concurrent nearshore placement of dredged sediment and the role of alongshore transport. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 151, 05024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putsy, N.P.; Moreira, M.E.S.A. Characteristics and longevity of beach nourishment at Praia da Rocha, Portugal. J. Coast. Res. 1992, 8, 660–676. [Google Scholar]

- Stive, M.J.F.; de Schipper, M.A.; Luijendijk, A.P.; Aarninkhof, S.G.J.; van Gelder-Maas, C.; van Thiel de Vries, J.S.M.; de Vries, S.; Henriquez, M.; Marx, S.; Ranasinghe, R. A new alternative to saving our beaches from sea-level rise: The sand engine. J. Coast. Res. 2013, 29, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.A.; Silveira, T.M.; Teixeira, S.B. Beach nourishment practice in mainland Portugal (1950–2017): Overview and retrospective. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 192, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, L.; Capobianco, M.; Dette, H.H.; Lechuga, A.; Spanhoff, R.; Stive, M.J.F. A summary of European experience with shore nourishment. Coast. Eng. 2002, 47, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.; Brampton, A.; Capobianco, M.; Dette, H.H.; Hamm, L.; Laustrup, C.; Lechuga, A.; Spanhoff, R. Beach nourishment projects, practices, and objectives—A European overview. Coast. Eng. 2002, 47, 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Wetzel, L.; Williams, A.T. Aspects of coastal erosion and protection in Europe. J. Coast. Conserv. 2015, 19, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.A.; Gomes, E.; Rodrigues, A. Dredging and beach nourishment: A sustainable sediment management approach in Costa da Caparica beach (Portugal). In Proceedings of the Dredging 2015 Conference in Moving and Managing Sediments, Savannah, GA, USA, 19–22 October 2015; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, D.; Pais-Barbosa, J.; Baptista, P.; Silva, P.A.; Bernardes, C.; Pinto, C. Beach response to a shoreface nourishment (Aveiro, Portugal). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, F. Evaluation of coastal protection strategies at Costa da Caparica (Portugal): Nourishments and Structural Interventions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.D.; Lopes, A.M.; Moniz, G.; Ramos, L.; Taborda, R. Coastal Zone Management. The Challenge of Changing. Report of the Littoral Task Force. Lisboa, Portugal. 2014. Available online: https://conselhonacionaldaagua.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/8/6/13869103/relatrio_final_gtl_20_11_2014.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025). (In Portuguese).

- Vicente, C.M.; Clímaco, M. Trecho de Costa do Douro ao Cabo Mondego: Caracterização Geral do Processo Erosivo; LNEC-Proc. 0604/011/17744. Report 253/2012–DHA/NEC; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- van Westen, B.; Luijendijk, A.P.; de Vries, S.; Cohn, N.; Leijnse, T.W.B.; de Schipper, M.A. Predicting marine and aeolian contributions to the Sand Engine’s evolution using coupled modelling. Coast. Eng. 2024, 188, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.C.; Frey, A.E. Shoreline Change Modeling Using One-Line Models: General Model Comparison and Literature Review. US Army Corps of Engineeres (No. CHETN-II-55). 2013. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA591362.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Cantasano, N.; Boccalaro, F.; Ietto, F. Assessing of detached breakwaters and beach nourishment environmental impacts in Italy: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 195, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira, C.P.; Silva, A.N.; Taborda, R.; Andrade, C.F. Coastline evolution of Portuguese low-lying sandy coast in the last 50 years: An integrated approach. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 8, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.; Matias, A. Portugal. In Coastal Erosion and Protection in Europe; Pranzini, E., Williams, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; p. 457. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, M.; Coelho, C.; Jesus, A.; Alves, F.; Marto, M. Data Base #4–Coastal Defense Interventions-Case Study (Ovar); Project INCCA-Integrated Climate Change Adaptation for Resilient Communities (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-030842); University of Aveiro: Aveiro, Portugal, 2021; Available online: https://incca.web.ua.pt/index.php/base-de-dados-4/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Tavares, A.O.; Barros, J.L.; Freire, P.; Santos, P.O.; Perdiz, L.; Fortunato, A.B. A coastal flooding database from 1980 to 2018 for the continental Portuguese coastal zone. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 135, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro-Barros, J.E.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Coastal flood mapping with two approaches based on observations at Furadouro, Northern Portugal. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Silva, R.; Vitorino, J. Contribuição para o estudo do clima de agitação marítima na costa portuguesa. In Proceedings of the 2as Jornadas Portuguesas de Engenharia Costeira e Portuária, Sines, Portugal, 17−19 October 2001; Associação Nacional de Navegação: Sines, Portugal, 2001. CD-ROM. p. 20. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.S.B.F.; Fortunato, A.B.; Freire, P. Beach nourishment protection against storms for contrasting backshore typologies. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.L.; Baldock, T.E. Laboratory investigation of nourishment options to mitigate sea level rise induced erosion. Coast. Eng. 2020, 161, 103769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, A.; Christiaanse, J.C.; Luijendijk, A.P.; Schipper, M.A.; Ranasinghe, R. Parameter uncertainty in medium-term coastal morphodynamic modeling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente. Programa COSMO. Available online: https://cosmo.apambiente.pt (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Himmelstoss, E.A.; Henderson, R.E.; Farris, A.S.; Kratzmann, M.G.; Bartlett, M.K.; Ergul, A.; Mcan-Drews, J.; Cibaj, R.; Zichichi, J.L.; Thieler, E.R. Digital Shoreline Analysis System Version 6.0: U.S. Geological Survey Software Release. 2024. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/whcmsc/science/digital-shoreline-analysis-system-dsas (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Fletcher, C.H.; Romine, B.M.; Genz, A.S.; Barbee, M.M.; Dyer, M.; Anderson, T.R.; Lim, C.S.; Vitousek, S.; Bochicchio, C.; Richmond, B.M. National Assessment of Shoreline Change: Historical Shoreline Changes in the Hawaiian Islands. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011-1051. 2012. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2011/1051/pdf/ofr2011-1051_report_508_rev052512.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Vicente, C.; Címaco, M. Shoreline Evolution. Development and Application of a Numerical Model; Report ICT/ITH-42; Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003; 167p. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.S.B.F.; Freire, P.; Sancho, F.; Vicente, C.M.; Clímaco, C. Rehabilitation and protection of Colwyn Bay beach: Case study. J. Coast. Res. 2011, II, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Dodet, G.; Bertin, X.; Taborda, R. Wave climate variability in the North-East Atlantic Ocean over the last six decades. Ocean Model. 2010, 31, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, J.W. Incipient wave breaking. Coast. Eng. 1991, 15, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.M.; Clímaco, M.; Bertin, X. Agitação Marítima e Transporte Sólido Litoral na Costa de Aveiro; LNEC-Proc. 0604/011/17744. Rel. 164/2013–DHA/NEC; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, C.M.; Clímaco, M. Trecho de Costa a sul de Espinho: Simulação Numérica do Processo Erosivo e de Alternativas de Intervenção; LNEC-Proc. 0604/011/17744. Relatório 101/2014–DHA/NEC; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. (In Portuguse) [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, C.M.; Clímaco, M. Evolução Costeira do Douro ao Cabo Mondego: Proposta de uma Metodologia de Estudo; LNEC-Proc. 0604/112/20285. Relatório 380/2015–DHA/NEC; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Dean, R.G. Equilibrium Beach Profiles: U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts; Ocean Engineering Report, No. 12; University of Delaware: Newark, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, L.S.; Finckl, C.W. The problem of critically eroded areas (CEA): An evaluation of Florida beaches. J. Costal Res. 1998, 11–18. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25736114 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Luijendijk, A.; Hagenaars, G.; Ranasinghe, R.; Baart, F.; Donchyts, G.; Aarninkhof, S. The State of the World’s Beaches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira-Canelas, S.; Sancho, F.; Trigo-Teixeira, A. A coastal defense work plan 40 years later: Review and evaluation of the Espinho case study in Portugal. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 148, 05022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, J.W. Alongshore sediment transport rate. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean. Eng. 1991, 117, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type and Zone | Date [yyyy-mm-dd] or [yyyy-mm] |

|---|---|

| Total beach surveys and orthophotos; from Cortegaça to Torrão do Lameiro beaches | 2018-09-02, 2019-05-15, 2020-05-18, 2021-03-03, 2021-04-27 |

| Topo-bathymetric surveys; from Esmoriz to Furadouro beaches | 2018-09, 2019-07, 2020-07 |

| Total profile surveys; between Esmoriz and Furadouro beaches | 2019-01, 2019-05, 2020-01, 2021-01, 2021-04(/5) |

| Emerged profile surveys; between Esmoriz and Torrão do Lameiro beaches | 2018-08, 2018-11, 2019-02, 2019-05, 2019-07, 2019-11, 2020-01, 2020-04, 2020-07, 2020-10, 2021-01, 2021-04 |

| Dates of Coastline Position [dd/mm/yyyy–dd/mm/yyyy] | Elapsed Time [Years] | Uncertainty of Evolution Rate [m/year] |

|---|---|---|

| 09/02/2018–15/05/2019 | 1.25 | 7.9 |

| 15/05/2019–18/05/2020 | 1 | 9.9 |

| 18/05/2020–03/03/2021 | 0.83 | 11.9 |

| 09/02/2018–03/03/2021 | 3.08 | 3.2 |

| Parameter 1 | Value [Unit] |

|---|---|

| Cell alongshore length | 50 [m] |

| Total number of cells | 795 [-] |

| Initial X-axis cell | 60,300 [m] |

| Final X-axis cell | 100,000 [m] |

| Time step | 0.05 [day] |

| Simulation period | 20 [year] |

| Initial shoreline date | 21 August 2021 |

| Wave climate input frequency | 1 [day] |

| Angle between cross-shore and geographic north (clockwise) | 283 [°] |

| Sea level: mean sea level (MWL) | 0 [m ALTH38] |

| Number of wave climates (at −15 m ALTH38) | 20 [-] |

| Beach sediment median grain diameter (D50) | 0.3 [mm] |

| Bottom slope at breaking zone 2 | 1:70 [-] |

| Kamphuis formulation coefficient 2 | 0.82 [-] |

| Dean’s beach profile coefficient (A) 3 | 0.125 |

| Thickness of profile’s erodible layer (between berm crest, at 4 m ALTH38, and sea limit of active profile, at −13 m ALTH38) | 17 [m] |

| Data Type and Zone | Erosion | Accretion | Balance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area [m2] | Volume [m3] | Area [m2] | Volume [m3] | Area [m2] | Volume [m3] | Average ∆z [m] | |

| Beach surveys; from Cortegaça to Furadouro | 337,681 | −839,761 | 219,490 | 142,458 | 557,171 | −697,303 | −1.25 |

| Topobathymetric surveys; from Esmoriz to Furadouro | 12,472,854 | −3,191,332 | 9,144,007 | 1,707,102 | 21,616,861 | −1,484,230 | −0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, F.S.B.F.; Sancho, F.; Rilo, A.; Nahon, A. Modelling the Longevity of Beach Nourishment and the Influence of a Detached Breakwater. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122251

Oliveira FSBF, Sancho F, Rilo A, Nahon A. Modelling the Longevity of Beach Nourishment and the Influence of a Detached Breakwater. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122251

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Filipa S. B. F., Francisco Sancho, Ana Rilo, and Alphonse Nahon. 2025. "Modelling the Longevity of Beach Nourishment and the Influence of a Detached Breakwater" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122251

APA StyleOliveira, F. S. B. F., Sancho, F., Rilo, A., & Nahon, A. (2025). Modelling the Longevity of Beach Nourishment and the Influence of a Detached Breakwater. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122251