Physiological and Agronomic Responses of Adult Citrus Trees to Oxyfertigation Under Semi-Arid Drip-Irrigated Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Conditions and Plant Material

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Dissolved Oxygen (DO) and Soil Oxygen Diffusion Rate (ODR)

2.2.2. Soil Physicochemical and Microbiological Analyses

2.2.3. Soil Respiration

2.2.4. Midday Stem Water Potential

2.2.5. Leaf Gas Exchange

2.2.6. Leaf Mineral Composition

2.2.7. Vegetative Growth

2.2.8. Root Biomass

2.2.9. Yield and Fruit Quality

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Conditions and Irrigation Water Applied During the Experimental Period

3.2. Effects of Oxyfertigation on Soil

3.2.1. Dissolved Oxygen in Irrigation Water and Soil Oxygen Diffusion Rate

3.2.2. Soil Respiration

3.2.3. Soil Chemical Composition

3.2.4. Soil Microbiology and Nematode Phytopathology

3.3. Effects of Oxyfertigation in the Plant

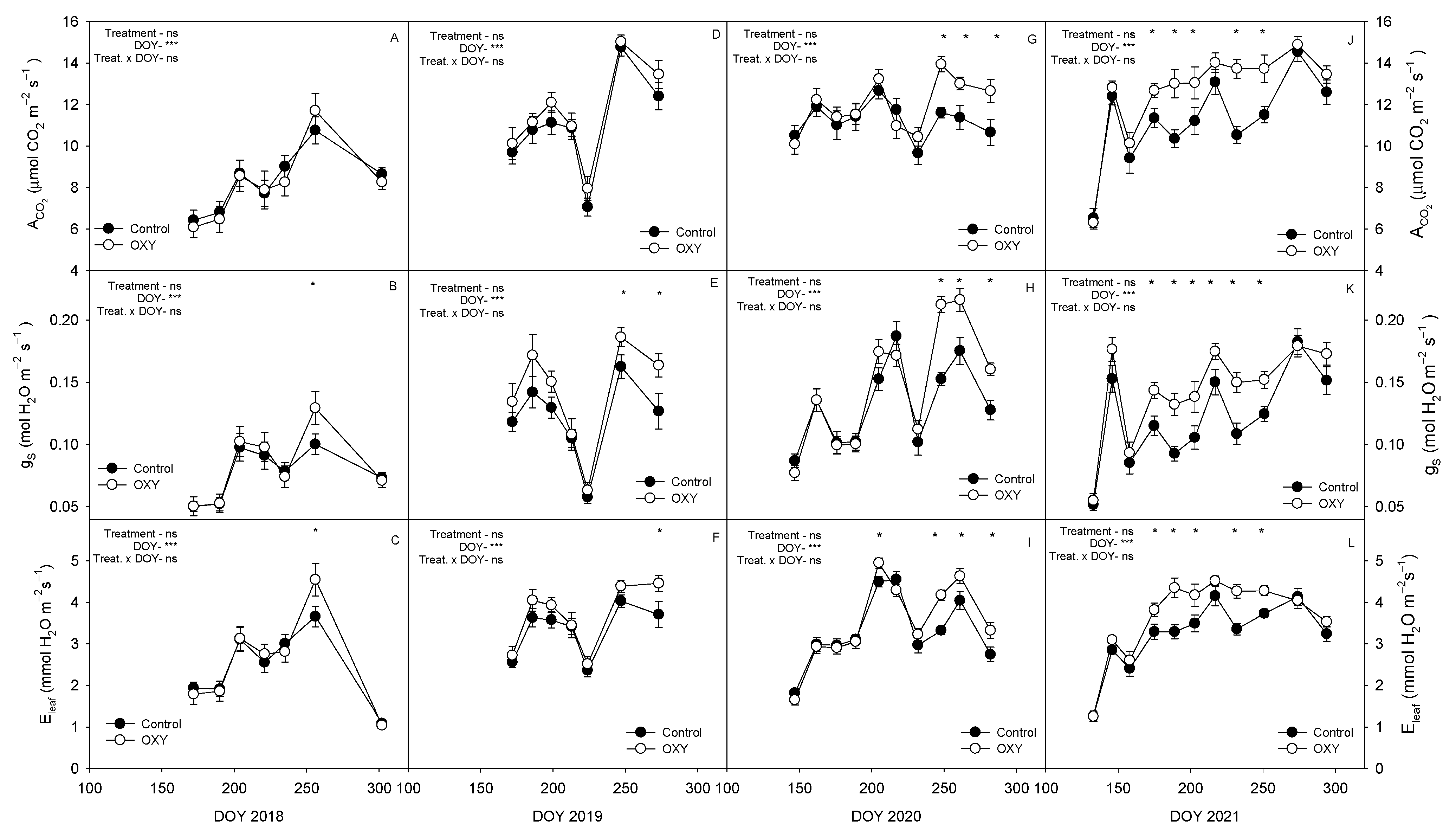

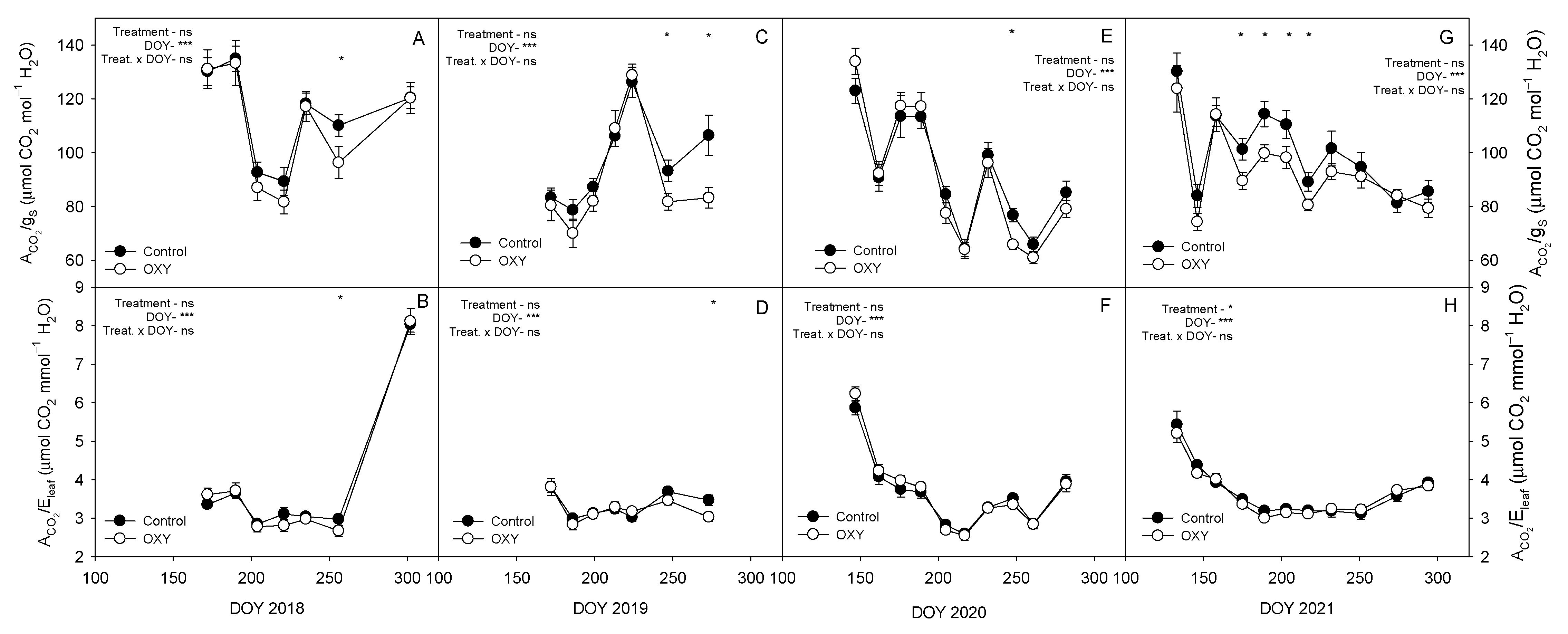

3.3.1. Plant Water Relations and Leaf Gas Exchange

3.3.2. Crop Growth

3.3.3. Root Biomass Distribution

3.3.4. Leaf Mineral Nutrition

3.3.5. Yield

3.3.6. Fruit Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Oxygenation and Microbial Response

4.2. Nutrient Dynamics and Soil-Plant Interactions

4.3. Plant Physiological Responses

4.4. Agronomic Responses: Yield and Fruit Quality

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| YWUE | Crop water use efficiency |

| IMIDA | Instituto Murciano de Investigación y Desarrollo Agrario y Medioambiental |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| ET0 | Reference evapotranspiration |

| ETc | Crop evapotranspiration |

| Kc | Crop coefficient |

| VPD | Vapor Pressure Deficit |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| ODR | Soil oxygen diffusion rate |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| Ψstem | Midday stem water potential |

| ACO2 | Net photosynthesis rate |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| Eleaf | Leaf transpiration rate |

| ACO2/Eleaf | Instantaneous leaf water use efficiency |

| ACO2/gs | Intrinsic leaf water use efficiency |

| TCSA | Trunk cross-sectional area |

| AGRtrunk | Absolute growth rate of the TCSA |

References

- MAPA. Anuario de Estadística Agraria 2023. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/estadistica/temas/publicaciones/anuario-de-estadistica (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- CARM. Anuario de Estadística Agraria de Murcia 2023–2024; Consejería de Agua, Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca, Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2024.

- Fernández, J.E.; Alcón, F.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Hernández-Santana, V.; Cuevas, M.V. Water use indicators and economic analysis for on-farm irrigation decision: A case study of a super high density olive tree orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 233, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-D.; Niu, W.-Q.; Gu, X.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, B.-J.; Zhao, Y. Crop yield and water use efficiency under aerated irrigation: A meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 210, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Junejo, A.R.; Midmore, D.J.; Soomro, S.A. Significance of aerated drip irrigation: A comprehensive review. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 321, 109886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinski, J.; Stępniewski, W. Soil Aeration and Its Role for Plants, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret-Lennard, E.G. The interaction between water logging and salinity in higher plants: Causes, consequences and implications. Plant Soil 2003, 253, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, B.D.; Ehlig, C.F.; Stolzy, L.H.; Graham, L.E. Forrow and trickle irrigation: Effects on soil oxygen and ethylene and tomato yield. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeus, R.P.; Witte, J.P.M.; van Bodegom, P.M.; van Dam, J.C.; Aerts, R. Critical soil conditions for oxygen stress to plant roots: Substituting the Feddes-function by a process-based model. J. Hydrol. 2008, 360, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.M.; Pérez Pérez, J.G. Oxifertirrigación química en el cultivo de plantas de pimiento en condiciones salinas. Agrícola Vergel 2019, 416, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Butter, T.S.; Samanta, A.; Singh, G.; Kumar, M.; Dhotra, B.; Yadab, N.K.; Choudhary, R.S. Soil compaction and their management in farming systems: A review. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2018, 6, 2302–2313. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Olmedo, M.; Ortiz, M.; Selles, G. Effects of transient soil waterlogging and its importance for rootstock selection. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 75, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Environmental Soil Physics: Fundamentals, Applications, and Environmental Considerations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–771. [Google Scholar]

- Neira, J.; Ortiz, M.; Morales, L.; Acevedo, E. Oxygen diffusion in soils: Understanding the factors and processes needed for modeling. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 75, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letey, J.; Stolzy, L.H. Measurement of oxygen diffusion rates with the platinum microelectrode. I–III. Hilgardia 1964, 35, 545–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, J.; Hedstrom, W.E.; Scott, F.R. Oxygen Diffusion Rate Relationships Under Three Soil Conditions; Life Sciences and Agriculture Experiment Station: Geneva, NY, USA, 1980; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, F.J.; Knight, J.H. Oxygen transport to plant roots: Modeling for physical understanding of soil aeration. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, F.J.; Knight, J.H.; Kelliher, F.M. Oxygen transport in soil and the vertical distribution of roots. Aust. J. Soil Res. 2007, 45, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, M.C. Oxygen deficiency and root metabolism: Injury and acclimation under hypoxia and anoxia. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 48, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Bailey-Serres, J. Flood adaptive traits and processes: An overview. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Colmer, T.D.; Pedersen, O.; Nakazono, M. Regulation of root traits for internal aeration and tolerance to soil waterlogging–flooding stress. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, K.Y.; Chun, H.C. Characteristics of Maize Roots under Subsurface Drip Irrigation through Various Oxygen Treatment. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2023, 56, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberbush, M.; Gornat, B.; Goldberg, D. Effect of irrigation from a point source (trickling) on oxygen flux and on root extension in the soil. Plant Soil 1979, 52, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.P.; Su, N.; Midmore, D.J. Oxygation enhances yield and water productivity of vegetables. Adv. Agron. 2005, 88, 313–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.G.; Bhattarai, S.P.; Balsys, R.J.; Walsh, K.B.; Midmore, D.J. Continuous injection of hydrogen peroxide in drip irrigation—Application to field crops. Agronomy 2025, 15, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, M.; Yamanaka, K. Synergistic disinfection and removal of biofilms by a sequential two-step treatment with ozone followed by hydrogen peroxide. Water Res. 2014, 64, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japhet, N.; Tarchitzky, J.; Chen, Y. Effectiveness of hydrogen peroxide treatments in preventing biofilm clogging in drip irrigation systems applying treated wastewater. Biofouling 2022, 38, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palencia, P.; Martínez, F.; Vázquez, M.A. Oxyfertigation and transplanting conditions of strawberries. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrestarazu, M.; Mazuela, P.C. Effect of slow-release oxygen supply by fertigation on horticultural crops under soilless culture. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 106, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfa, O.; Cáceres, R.; Gurí, S. Oxyfertigation: A new technique for soilless culture under Mediterranean conditions. Acta Hortic. 2005, 697, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, R.; Bonachela, S.; Magán, J. Respuesta de un cultivo de pimiento en sustrato de perlita a la mejora de la oxigenación del medio radicular. Acta Hortic. 2006, 46, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, S.P.; Huber, S.; Midmore, D.J. Aerated subsurface irrigation water gives growth and yield benefits to Zucchini, vegetable soybean and cotton in heavy clay soils. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2004, 144, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elhady, S.A.; El-Gawad, H.G.A.; Ibrahim, M.F.M.; Mukherjee, S.; Elkelish, A.; Azab, E.; Gobouri, A.A.; Farag, R.; Ibrahim, H.A.; El-Azm, N.A. Hydrogen peroxide supplementation in irrigation water alleviates drought stress and boosts growth and productivity of potato plants. Sustainability 2021, 13, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, W.; Jing, B.; Liu, L. Modulation of soil aeration and antioxidant defenses with hydrogen peroxide improves the growth of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, P.M.; Ferreyra, R.; Barrera, C.; Zúñiga, C.; Gurovich, L. Effect of injecting hydrogen peroxide into heavy clay loam soil on plant water status, net CO2 assimilation, biomass, and vascular anatomy of avocado trees. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 69, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanauskas, C.F.; Stolzy, L.H.; Klotz, L.J.; DeWolfe, T.A. Adequate soil-oxygen supplies increase nutrient concentrations in citrus seedlings. Calif. Agric. 1964, 18, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Noah, I.; Nitsan, I.; Cohen, B.; Kaplan, G.; Friedman, S.P. Soil aeration using air injection in a citrus orchard with shallow groundwater. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorenbos, J.; Pruitt, W.O. Crop Water Requirements; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper Number 24; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1977; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration. In Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Boletín Oficial de la Región de Murcia (BORM). Núm 106, 2002, Orden Del 24 de Abril de 2002. In Por la Que Regulan Las Normas Técnicas de Producción Integrada en el Cultivo de Cítricos; Suplemento Núm 1 Del BORM 9 de Mayo de 2002; Consejería de Agricultura, Agua y Medio Ambiente: Murcia, Spain, 2002; pp. 188–207.

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Sun, J. Effects of oxygenated irrigation on root morphology, fruit yield, and water–nitrogen use efficiency of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 5582–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafuso, E.J.; Fisher, P.R. Oxygenation of irrigation water during propagation and container production of bedding plants. HortScience 2017, 52, 1608–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, E.R.; Erickson, A.E. The measurement of oxygen diffusion in the soil with a platinum microelectrode. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1952, 16, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I. An examination of the Degtjareff method and a proposed modification of the chromic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 34, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledian, Y.; Brevick, E.C.; Pereira, P.; Cerdá, A.; Fattah, M.A.; Tazikeh, H. Modeling soil cation exchange capacity in multiple countries. Catena 2017, 158, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenbrink, M. Estimating nematode populations by some selected methods. Nematology 1960, 6, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan, H.; Shackel, K.A. Stem-water potential as a sensitive indicator of water stress in prune trees (Prunus domestica L. cv French). J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C. Measurements of plant water status by pressure chamber technique. Irrig. Sci. 1988, 9, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Caemmerer, S.; Farquhar, G.D. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 1981, 153, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Allen, L.H. Carbon dioxide and water vapour exchange of leaves on field-grown citrus trees. J. Exp. Bot. 1982, 33, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvertsen, J.P. Light acclimation in citrus leaves. II. CO2 assimilation and light, water and nitrogen use efficiency. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1984, 109, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Machado, C. Some aspects of citrus ecophysiology in subtropical climates: Re-visiting photosynthesis under natural conditions. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 19, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; Robles, J.M.; Botía, P. Effects of deficit irrigation in different fruit growth stages on ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit trees in semi-arid conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 133, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No. 1799/2001 of the Commission of 12 September 2001 Establishing Marketing Standards for citrus; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; Volume 248, pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grable, A.R. Soil aeration and plant growth. Adv. Agron. 1966, 18, 57–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, F.E.; Manzoni, S.; Chenu, C. Responses of soil heterotrophic respiration to moisture availability: An exploration of processes and models. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 59, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Detto, M.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Allen, M.F. Multiscale analysis of temporal variability of soil CO2 production as influenced by weather and vegetation. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1589–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Noah, I.; Friedman, S.P. Review and evaluation of root respiration and of natural and agricultural processes of soil aeration. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 180119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Noah, I.; Friedman, S.P. Oxygation of clayey soils by adding hydrogen peroxide to the irrigation solution: Lysimetric experiments. Rhizosphere 2016, 2, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zou, H.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Sun, H.; Yu, D. The effects of aerated irrigation on soil respiration and the yield of the maize root zone. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdejo-Lucas, S.; McKenry, M.V. Management of the citrus nematode, Tylenchulus semipenetrans. J. Nematol. 2004, 36, 424–432. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, L.W. Nematode parasites of citrus. In Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture, 2nd ed.; Luc, M., Sikora, R.A., Bridge, J., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 437–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekora, N.; Crow, W. EENY-529/IN941: Citrus Nematode, Tylenchulus semipenetrans (Cobb 1913). EDIS 2013, 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karajeh, M.R.; Masoud, S.A. Oxamyl and hydrogen peroxide for the control of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica on tomato. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2008, 48, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neher, D.A. Role of nematodes in soil health and their use as bioindicators. J. Nematol. 2001, 33, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, S.P. Nematodes and soil health indicators. Phytopathology 2017, 6, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Crenshaw, C.; Green, L.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Stursova, M.; Zeglin, L.H. Pulse dynamics and microbial processes in aridland ecosystems. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, F.; Peiró, E.; Baixauli, C.; de Paz, J.M. Spontaneous plants improve the inter-row soil fertility in a citrus orchard but nitrogen lacks to boost organic carbon. Environments 2022, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.A.; Imbernón-Mulero, A.; Martínez-Álvarez, M.; Gallego-Elvira, B.; Maestre-Valero, J.F. Midterm effects of irrigation with desalinated seawater on soil properties and constituents in a Mediterranean citrus orchard. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 381, 109421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; Dodd, I.C.; Botía, P. Partial rootzone drying increases water-use efficiency of lemon Fino 49 trees independently of root-to-shoot ABA signalling. Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 39, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, H.; Tomás, M.; Martorell, S.; Flexas, J.; Hernández, E.; Rosselló, J.; Pou, A.; Escalona, J.-M.; Bota, J. From leaf to whole-plant water use efficiency (WUE) in complex canopies: Limitations of leaf WUE as a selection target. Crop J. 2015, 3, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.G.; Binkley, D.; Fownes, J.H. Age-related decline in forest productivity: Pattern and process. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1997, 27, 213–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, A.A.; Morgan, K.T.; Kadyampakeni, D.M. Spatial and temporal nutrient dynamics and water management of huanglongbing-affected mature citrus trees on florida sandy soils. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, J.E.; Álvarez-Herrera, J.G.; Alvarado-Sanabria, O.H. El estrés hídrico en cítricos (Citrus spp.): Una revisión. Orinoquia 2012, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berríos, P.; Temnani, A.; Zapata-García, S.; Sánchez-Navarro, V.; Zornoza, R.; Pérez-Pastor, A. Effect of deficit irrigation and mulching on the agronomic and physiological response of mandarin trees as strategies to cope with water scarcity in a semi-arid climate. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 324, 112572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, A.; Frías, J.; García-Tejero, I.; Romero, F.; Muriel, J.L.; Capote, N. Towards the improvement of fruit-quality parameters in citrus under deficit-irigation srategies. ISRN Agron. 2012, 2012, 940896. [Google Scholar]

- Gasque, M.; Martí, P.; Granero, B.; González-Altozano, P. Effects of long-term summer deficit irrigation on ‘Navelina’ citrus trees. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 169, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Seasons | ET0 (mm) | R (mm) | Irrigation Treatments (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | OXY | |||

| 2018 | 1246 | 304 | 588 | 548 |

| 2019 | 1192 | 512 | 547 | 547 |

| 2020 | 1160 | 334 | 539 | 538 |

| 2021 | 1138 | 385 | 470 | 470 |

| Average 2018–2021 | 1184 | 384 | 536 | 526 |

| Salinity | Soil Reaction and Organic Matter | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Treatment | CE (mS cm−1) | Chloride (meq 100 g−1) | Sulfate (% p/p) | Exchange Sodium (meq 100 g−1) | pH | Total Limestone (% p/p) | Active Limestone (% p/p) | Organic Matter (% p/p) | Organic Carbon (% p/p) | C/N |

| 2020 | Control | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 7.95 ± 0.09 | 30.20 ± 3.55 | 10.93 ± 1.31 | 1.98 ± 0.19 | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 6.73 ± 0.35 |

| OXY | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 7.94 ± 0.02 | 31.43 ± 1.29 | 11.11 ± 0.36 | 2.06 ± 0.13 | 1.20 ± 0.07 | 6.50 ± 0.19 | |

| 2021 | Control | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 7.45 ± 0.09 | 35.20 ± 3.00 | 13.93 ± 0.97 | 2.68 ± 0.27 | 1.55 ± 0.16 | 9.37 ± 0.33 |

| OXY | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.11 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.11 | 7.31 ± 0.05 | 35.23 ± 2.45 | 13.25 ± 0.59 | 2.35 ± 0.26 | 1.36 ± 0.15 | 8.97 ± 0.19 | |

| ANOVA | |||||||||||

| Treatment | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Year | ns | ns | ns | * | *** | ns | * | * | * | ns | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Primary Macronutrients | Secondary Macronutrients | Micronutrients | Cation Exchange Capacity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Treatment | Total Nitrogen (% p/p) | Soluble Nitric Nitrogen (mg kg−1) | Soluble Nitrate (mg kg−1) | Assimilable Phosphorous (mg kg−1) | Exchange Potassium (meq 100 g−1) | Exchange Calcium (meq 100 g−1) | Exchange Magnesium (meq 100 g−1) | Assimilable Boron (mg kg−1) | C.I.C. (meq 100 g−1) |

| 2020 | Control | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 22.23 ± 1.98 | 98.6 ± 8.9 | 148.3 ± 16.4 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 8.80 ± 0.28 | 3.21 ± 0.22 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 13.30 ± 0.57 |

| OXY | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 22.66 ± 2.93 | 100.3 ± 13.1 | 156.3 ± 6.8 | 1.08 ± 0.09 | 9.67 ± 0.59 | 2.82 ± 0.41 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 13.93 ± 1.13 | |

| 2021 | Control | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 40.00 ± 5.03 | 177.0 ± 22.3 | 121.3 ± 14.7 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 10.13 ± 0.74 | 3.89 ± 0.49 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 15.67 ± 1.35 |

| OXY | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 32.13 ± 13.74 | 142.0 ± 60.7 | 125.3 ± 8.7 | 1.05 ± 0.20 | 10.40 ± 0.77 | 3.79 ± 0.45 | 0.67 ± 0.09 | 15.77 ± 1.53 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||

| Treatment | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| Year | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Soil Microbiology | Nematode Phytopathology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Treatment | Aerobic Mesophilic (ufc g−1) | Molds and Yeasts (ufc g−1) | Actinomycetes (ufc g−1) | Tylenchulus spp. (Nematode 100 g−1) | Saprophytic Soil Nematodes (Nematode 100 g−1) |

| 2020 | Control | 17,733,333 ± 3,055,050 | 44,000 ± 5508 | 106,667 ± 3333 | 2144.7 ± 146.5 | 174.0 ± 37.7 |

| OXY | 21,000,000 ± 5,544,166 | 57,000 ± 15,000 | 126,667 ± 3333 | 719.7 ± 607.0 | 101.7 ± 126.2 | |

| 2021 | Control | 28,000,000 ± 3,333,333 | 130,000 ± 577 | 456,667 ± 577 | 931.0 ± 227.4 | 107.0 ± 21.9 |

| OXY | 24,666,667 ± 9,848,858 | 95,000 ±10,000 | 226,667 ± 10,000 | 574.0 ± 547.4 | 67.7 ± 35.2 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| Treatment | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | |

| Year | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Year | Treatment | AGRTrunk (cm2 Year−1) | Fresh Pruning Weight (kg Tree−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Control | 10.1 ± 1.10 | - |

| OXY | 7.8 ± 1.52 | - | |

| 2019 | Control | 10.2 ± 1.24 | 12.2 ± 0.91 |

| OXY | 11.5 ± 2.12 | 14.6 ± 1.58 | |

| 2020 | Control | 7.6 ± 0.99 | 14.0 ± 1.58 |

| OXY | 8.5 ± 1.52 | 18.0 ± 1.50 | |

| 2021 | Control | 4.4 ± 0.52 | 7.1 ± 0.82 |

| OXY | 6.3 ± 0.93 | 7.2 ± 0.70 | |

| 2018–2021 | 2019–2021 | ||

| Accumulated | Control | 22.2 ± 2.40 | 33.2 ± 2.43 |

| OXY | 22.5 ± 3.16 | 39.8 ± 3.04 | |

| ANOVA | |||

| Treatment | ns | * | |

| Year | *** | *** | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns |

| 2021 | Fine 0–15 cm | Thick 0–15 cm | Total 0–15 cm | Fine 15–30 cm | Thick 15–30 cm | Total 15–30 cm | Total Fine | Total Thick | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.80 ± 0.15 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.10 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.12 | 0.97 ± 0.15 | 0.23 ± 0.11 | 1.20 ± 0.04 |

| OXY | 0.65 ± 0.17 | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 1.64 ± 1.44 | 2.01 ± 1.39 | 1.02 ± 0.32 | 1.86 ± 1.55 | 2.87 ± 1.39 |

| ANOVA | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Primary Macronutrients | Secondary Macronutrients | Microelements | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Treatment | N (%) | P (%) | K (%) | Ca (%) | Mg (%) | Na (%) | Fe (ppm) | Cu (ppm) | Mn (ppm) | Zn (ppm) | B (ppm) |

| 2018 | Control | 2.61 ± 0.12 | 0.147 ± 0.004 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 4.49 ± 0.14 | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 79 ± 2.2 | 16 ± 1.6 | 35 ± 2.1 | 34 ± 2.6 | 271 ± 13 |

| OXY | 2.62 ± 0.14 | 0.149 ± 0.004 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 4.22 ± 0.20 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 84 ± 5.8 | 18 ± 2.2 | 38 ± 1.9 | 37 ± 4.1 | 272 ± 11 | |

| 2019 | Control | 2.77± 0.04 | 0.128 ± 0.004 | 0.35± 0.03 | 4.24 ± 0.15 | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 65 ± 2.0 | 23 ± 1.7 | 23 ± 2.2 | 19 ± 1.0 | 275 ± 9 |

| OXY | 2.87± 0.02 | 0.129 ± 0.003 | 0.44± 0.04 | 4.28 ± 0.13 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 72 ± 2.1 | 24 ± 1.2 | 23 ± 2.0 | 21 ± 1.3 | 281 ± 15 | |

| 2020 | Control | 2.60 ± 0.05 | 0.111 ± 0.003 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 4.20 ± 0.11 | 0.49± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 61 ± 2.6 | 22± 0.8 | 25 ± 1.1 | 19 ± 1.3 | 234 ± 14 |

| OXY | 2.63 ± 0.02 | 0.112 ± 0.002 | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 4.45 ± 0.15 | 0.45± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 62 ± 2.2 | 25± 1.6 | 27 ± 1.7 | 20 ± 0.8 | 268 ± 12 | |

| 2021 | Control | 2.87 ± 0.04 | 0.145 ± 0.003 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 4.91 ± 0.09 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 80 ± 4.2 | 21 ± 2.1 | 20 ± 0.8 | 26 ± 1.1 | 289 ± 10 |

| OXY | 2.93 ± 0.03 | 0.143 ± 0.004 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 5.01 ± 0.08 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 86 ± 4.4 | 20 ± 1.6 | 21 ± 1.5 | 26 ± 0.9 | 300 ± 9 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| Treatment | ns | ns | ns | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Year | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Year | Treatment | Yield (kg Tree–1) | Fruit Load (nº Fruit Tree–1) | Fruit Weight (g) | YWUE (kg m–3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Control | 77.9 ± 8.4 | 416 ± 56 | 197.9 ± 8.0 | 11.0 ± 1.20 |

| OXY | 79.3 ± 6.2 | 421 ± 45 | 199.0 ± 10.8 | 12.1 ± 0.95 | |

| 2019 | Control | 53.0 ± 9.3 | 270 ± 51 | 211.8 ± 9.8 | 8.4 ± 1.48 |

| OXY | 64.6 ± 10.1 | 336 ± 55 | 198.2 ± 8.8 | 10.2 ± 1.59 | |

| 2020 | Control | 64.6 ± 7.2 | 404 ± 52 | 168.8 ± 7.9 | 9.6 ± 1.07 |

| OXY | 79.2 ± 7.1 | 548 ± 61 | 152.0 ± 6.9 | 11.8 ± 1.06 | |

| 2021 | Control | 93.6 ± 7.4 | 635 ± 56 | 150.1 ± 5.2 | 16.4 ± 1.30 |

| OXY | 103.1 ± 8.8 | 725 ± 78 | 146.8 ± 5.2 | 18.1 ± 1.55 | |

| Accumulated | Accumulated | Mean | Mean | ||

| 2018–2021 | Control | 289.1 ± 27.3 | 1725 ± 174 | 170.6 ± 4.3 | 11.2 ± 1.06 |

| OXY | 326.2 ± 26.1 | 2030 ± 178 | 162.7 ± 3.3 | 12.9 ± 1.03 | |

| ANOVA | |||||

| Treatment | ns | * | ns | * | |

| Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Year | Treatment | Diameter (mm) | Height (mm) | External Color Index | Peel Thickness (mm) | Juice (%) | Pulp (%) | Peel (%) | Total Soluble Solids (°Brix) | Titratable Acidity (g L–1) | Maturity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Control | 80.5 ± 0.8 | 64.4 ± 0.7 | 19.8 ± 0.2 | 3.05 ± 0.09 bc | 54.8 ± 0.5 a | 3.4 ± 0.12 | 41.6 ± 0.6 c | 12.4 ± 0.2 bc | 11.4 ± 0.3 | 10.0 ± 0.20 |

| OXY | 81.6 ± 1.4 | 64.7 ± 0.9 | 20.5± 0.2 | 3.24 ± 0.09 ab | 52.7 ± 0.8 a | 3.3 ± 0.14 | 43.5 ± 0.8 c | 12.2 ± 0.2 c | 12.6 ± 0.2 | 9.7 ± 0.18 | |

| 2019 | Control | 82.0 ± 0.8 | 65.0 ± 0.7 | 20.1 ± 0.4 | 3.34 ± 0.11 a | 48.5 ± 0.9 b | 2.8 ± 0.16 | 47.7 ± 1.0 b | 11.1 ± 0.1 d | 12.7 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.19 |

| OXY | 80.8 ± 0.9 | 64.2 ± 0.9 | 19.6 ± 0.2 | 3.15 ± 0.08 abc | 43.3 ± 1.4 d | 2.7 ± 0.06 | 53.0 ± 1.4 a | 10.9 ± 0.2 d | 14.7 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.15 | |

| 2020 | Control | 75.7 ± 2.1 | 58.9 ± 1.8 | 18.8 ± 0.7 | 2.74 ± 0.08 de | 42.9 ± 0.8 d | 4.6 ± 0.81 | 51.4 ± 0.1 a | 12.6 ± 0.20 bc | 16.1 ± 0.3 | 7.3 ± 0.13 |

| OXY | 74.5 ± 1.7 | 57.8 ± 1.5 | 19.3 ± 0.5 | 2.51 ± 0.11 e | 45.2 ± 0.8 cd | 4.7 ± 0.90 | 49.0 ± 0.1 b | 13.4 ± 0.3 a | 18.7 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.20 | |

| 2021 | Control | 76.2 ± 1.2 | 57.2 ± 0.8 | 16.5 ± 0.3 | 2.65 ± 0.07 e | 48.1 ± 0.7 b | 2.4 ± 0.07 | 48.4 ± 0.6 b | 12.6 ± 0.1 bc | 15.1 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.09 |

| OXY | 75.2 ± 0.9 | 56.3 ± 0.5 | 17.0 ± 0.3 | 2.98 ± 0.08 cd | 47.2 ± 0.5 bc | 2.9 ± 0.20 | 48.8 ± 0.6 b | 12.9 ± 0.2 ab | 16.9 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 0.16 | |

| ANOVA | |||||||||||

| Treatment | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | * | ns | ** | * | |

| Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Treatment × Year | ns | ns | ns | * | *** | ns | *** | * | ns | ns | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Robles, J.M.; Hernández-Ballester, F.M.; Navarro, J.M.; Morote, E.I.; Botía, P.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G. Physiological and Agronomic Responses of Adult Citrus Trees to Oxyfertigation Under Semi-Arid Drip-Irrigated Conditions. Agriculture 2026, 16, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010075

Robles JM, Hernández-Ballester FM, Navarro JM, Morote EI, Botía P, Pérez-Pérez JG. Physiological and Agronomic Responses of Adult Citrus Trees to Oxyfertigation Under Semi-Arid Drip-Irrigated Conditions. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobles, Juan M., Francisco Miguel Hernández-Ballester, Josefa M. Navarro, Elisa I. Morote, Pablo Botía, and Juan G. Pérez-Pérez. 2026. "Physiological and Agronomic Responses of Adult Citrus Trees to Oxyfertigation Under Semi-Arid Drip-Irrigated Conditions" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010075

APA StyleRobles, J. M., Hernández-Ballester, F. M., Navarro, J. M., Morote, E. I., Botía, P., & Pérez-Pérez, J. G. (2026). Physiological and Agronomic Responses of Adult Citrus Trees to Oxyfertigation Under Semi-Arid Drip-Irrigated Conditions. Agriculture, 16(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010075