Siloxane and Nano-SiO2 Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Coatings Based on Recyclable Spent Mushroom Substrate: Excellent Performance, Controlled-Release Mechanism, and Effect on Plant Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

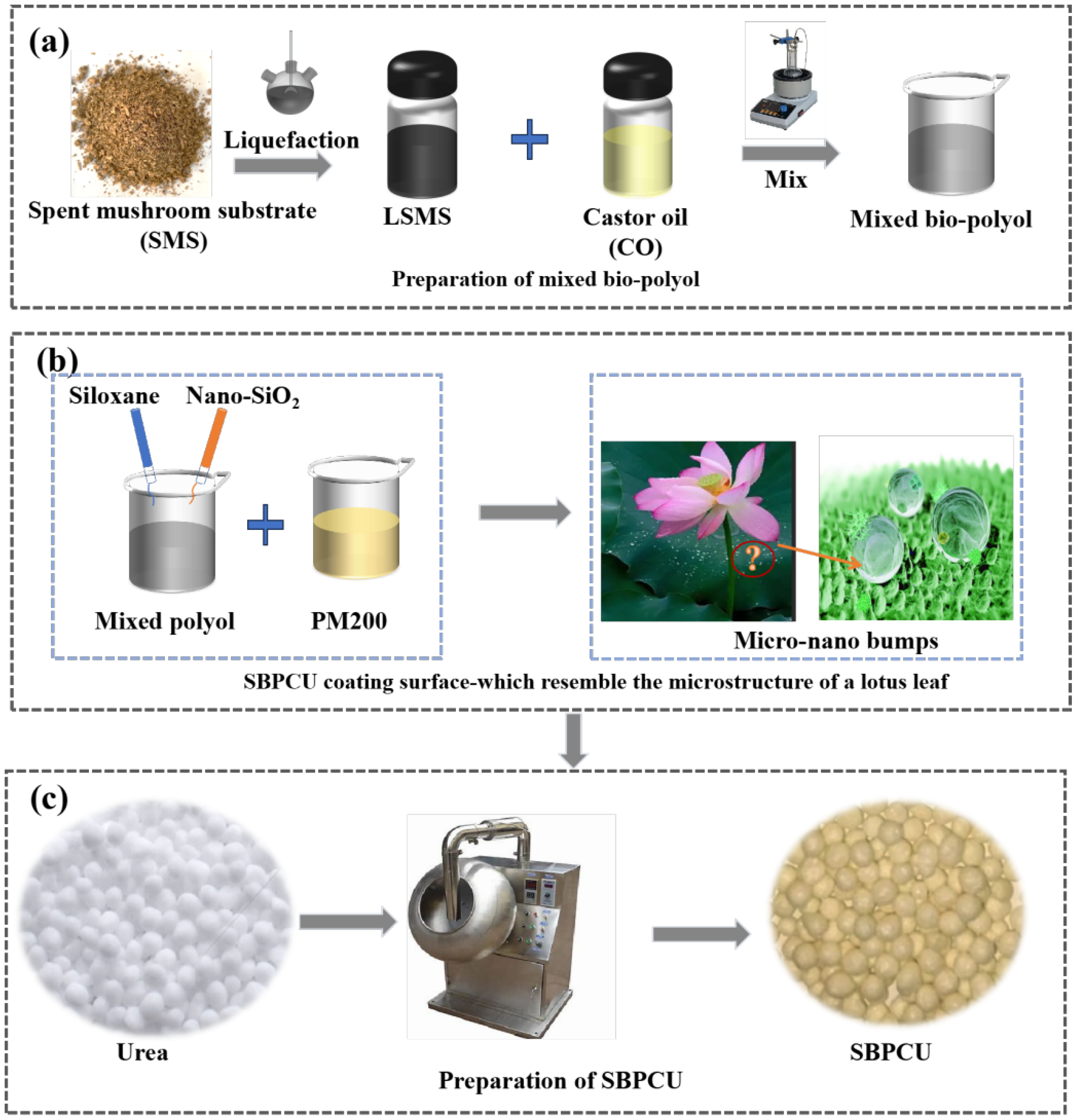

2.2. Synthesis of Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Polyurethane Coatings

2.3. Synthesis of Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer-Polyurethane-Coated Urea

2.4. Characterization of Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Polyurethane Coatings

2.4.1. Determination of Water Absorption

2.4.2. Determination of Porosity

2.5. Chemical Structure

2.6. Nitrogen Release Characteristics

2.7. Toxicity to Plants

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

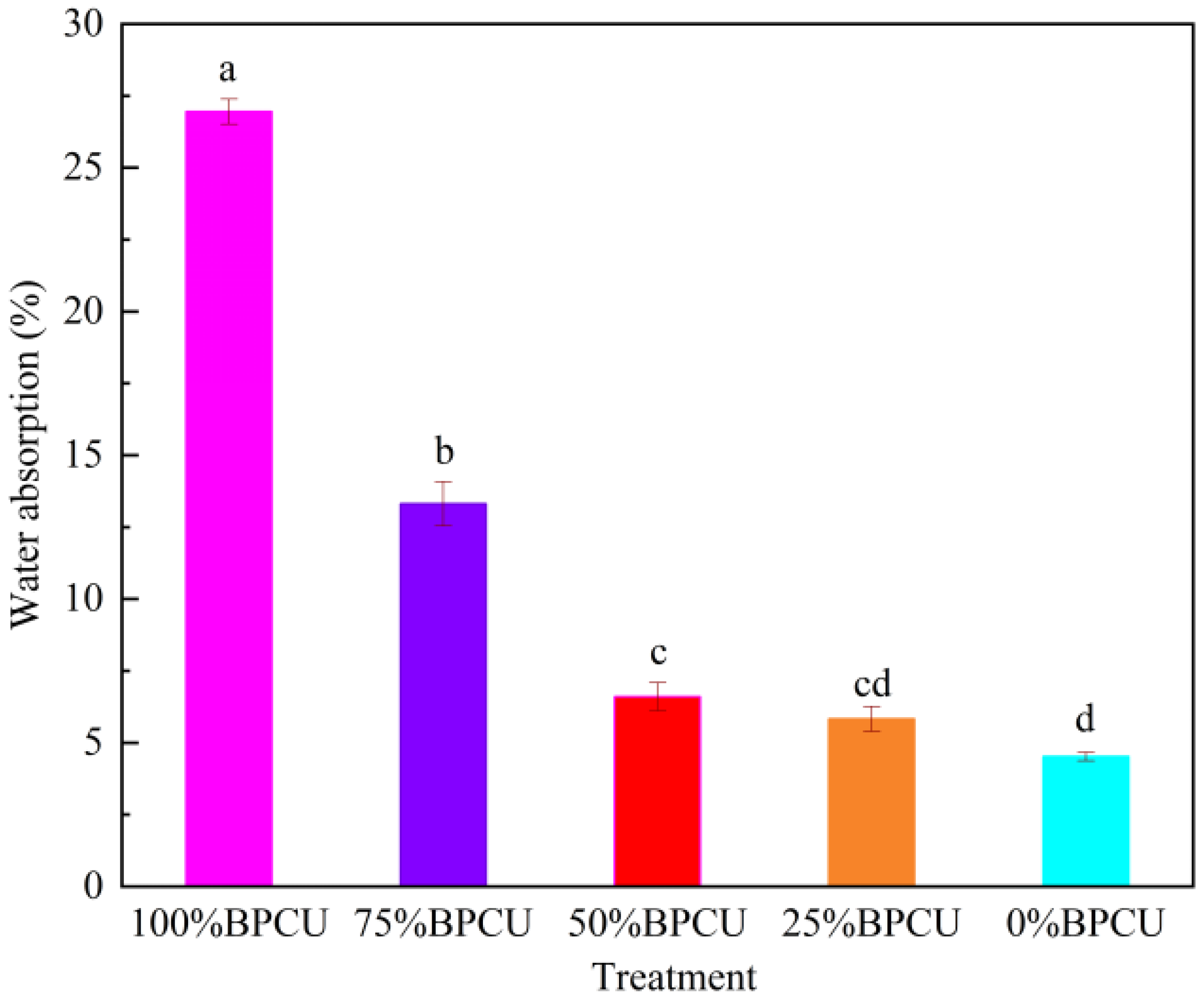

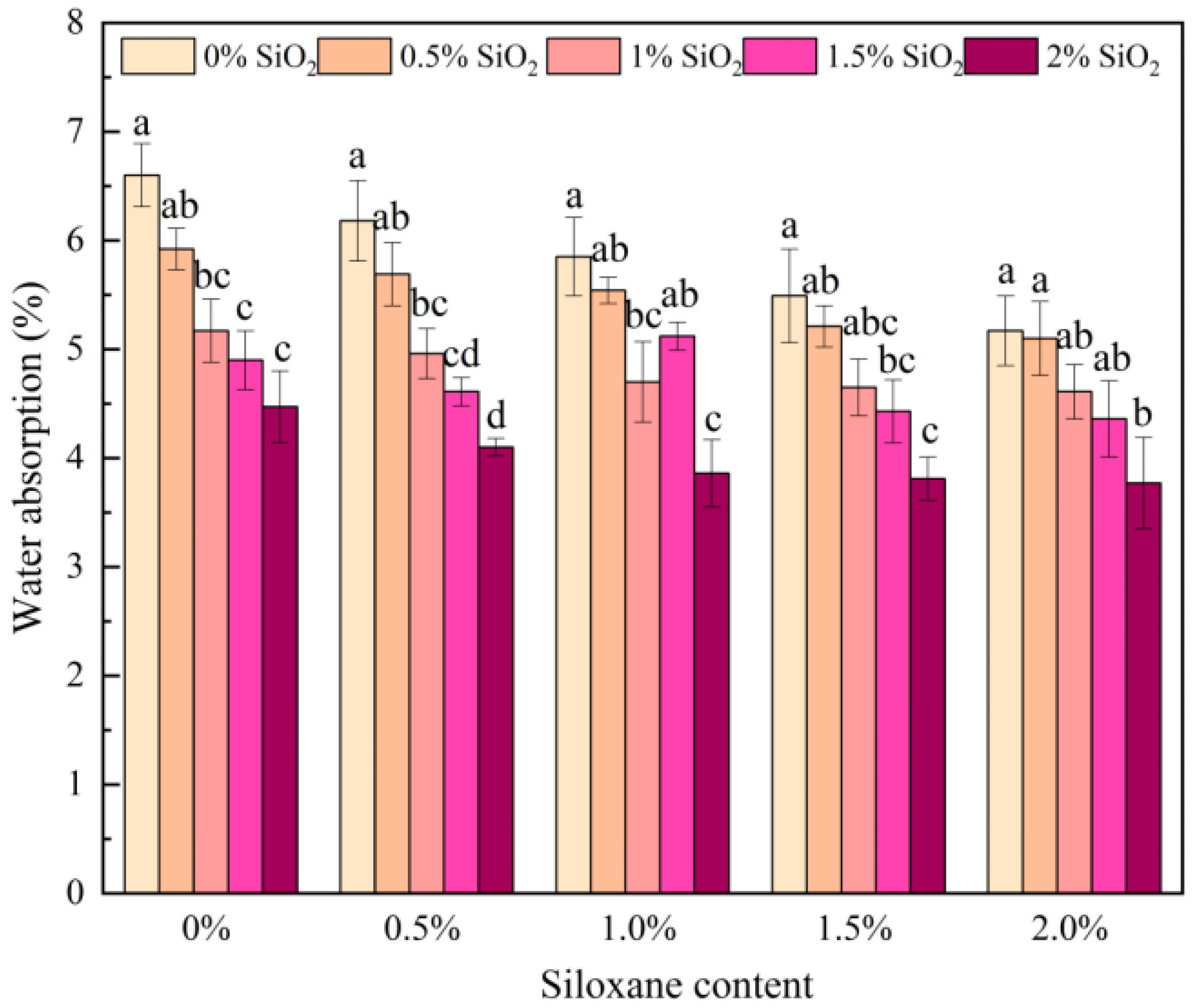

3.1. Water Absorption

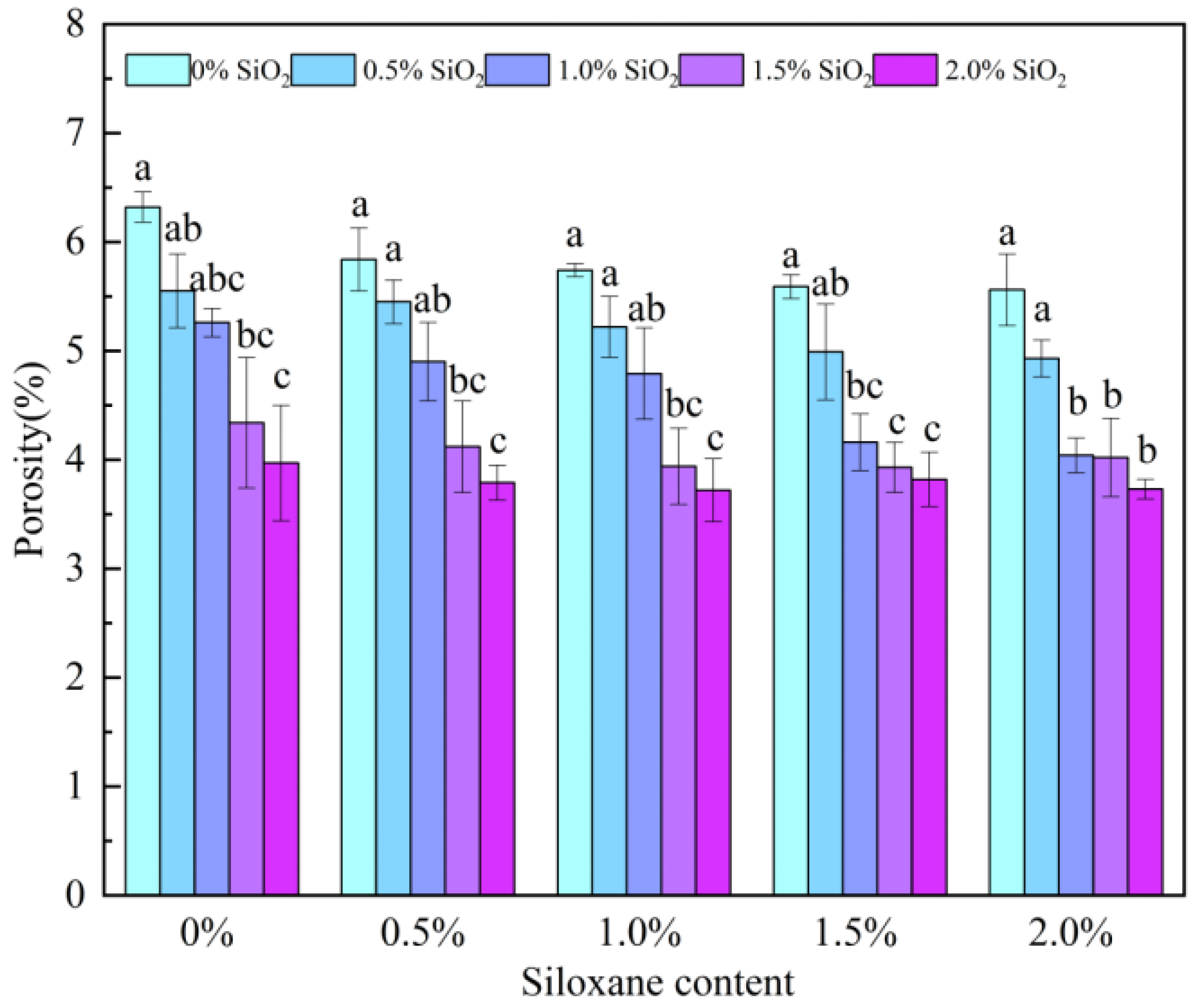

3.2. Porosity

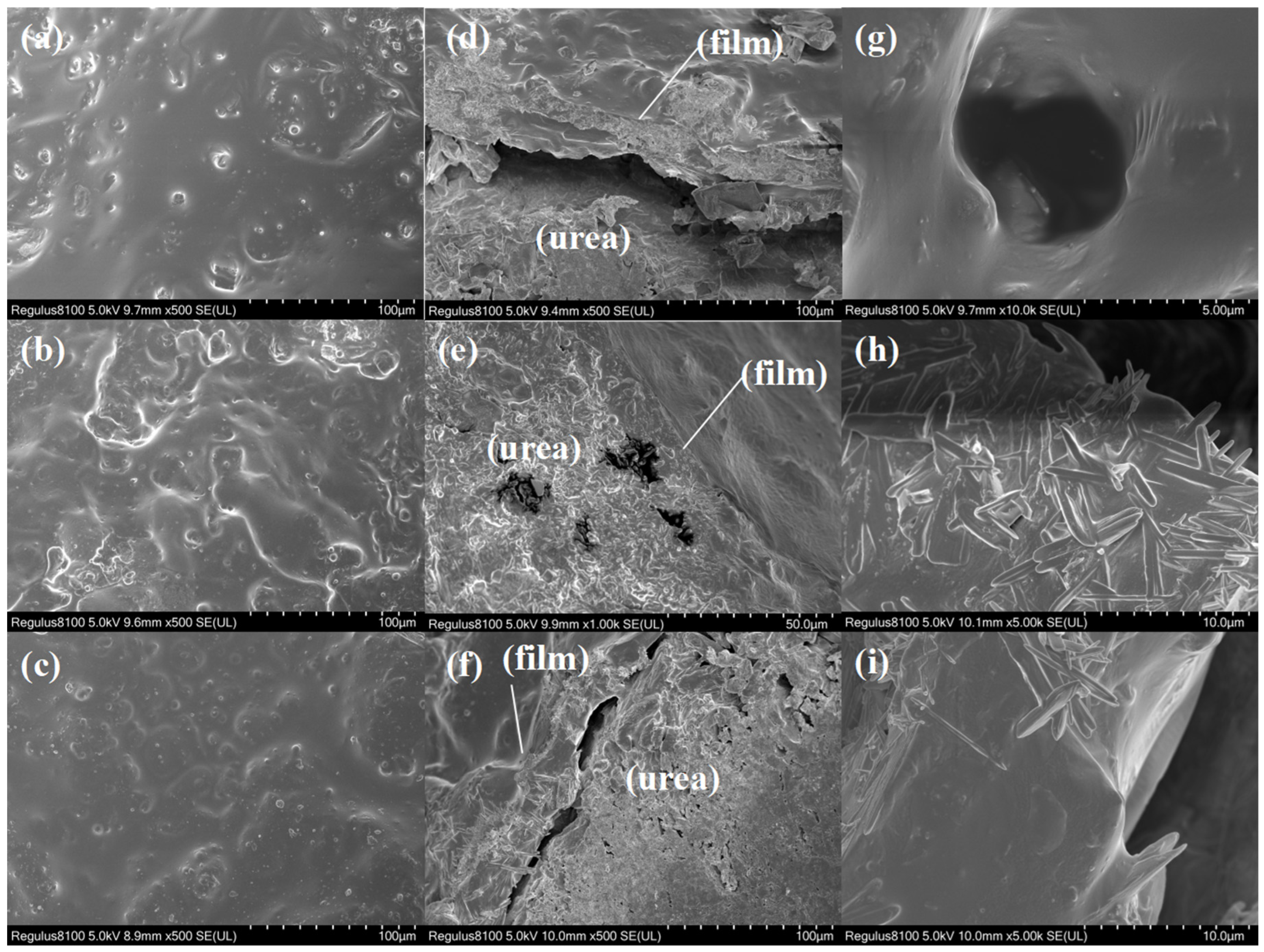

3.3. SEM and EDX Analysis

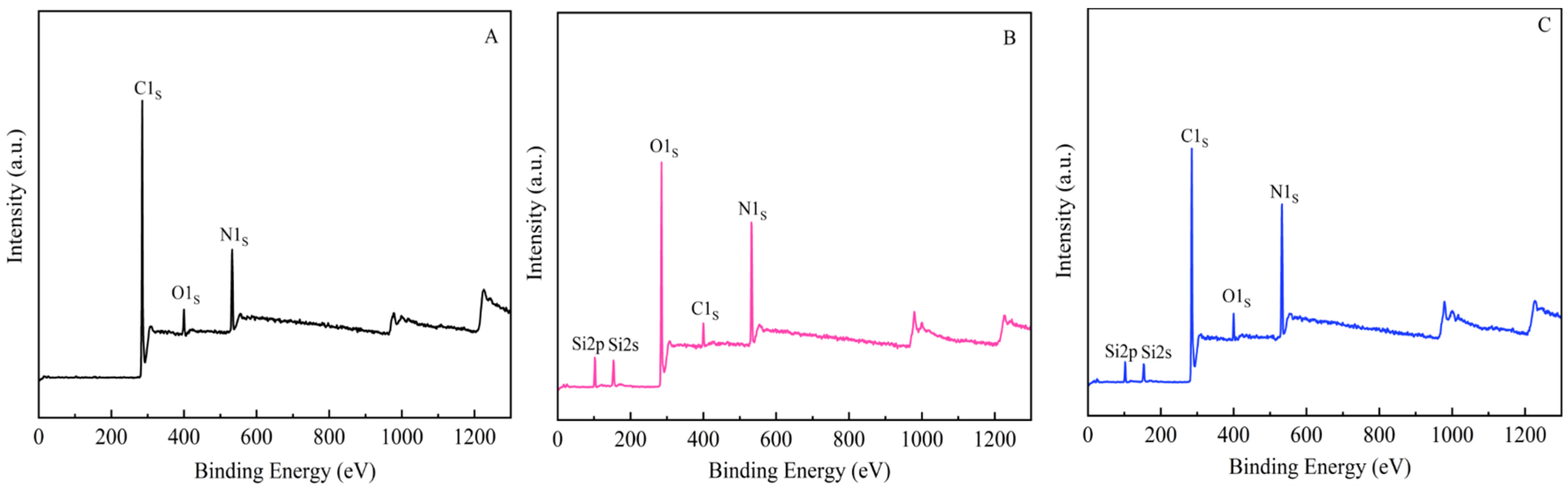

3.4. XPS Analysis

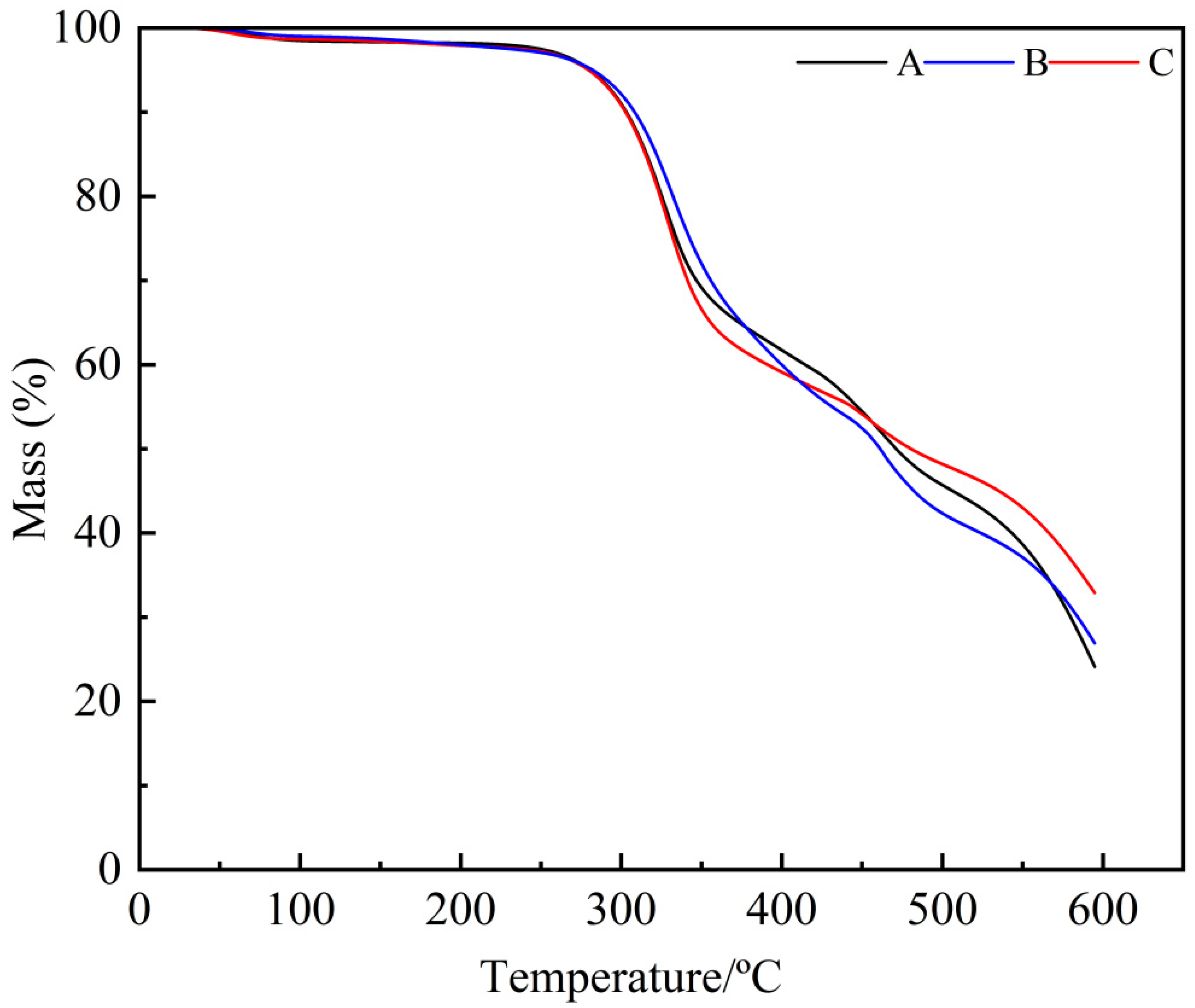

3.5. TGA Analysis

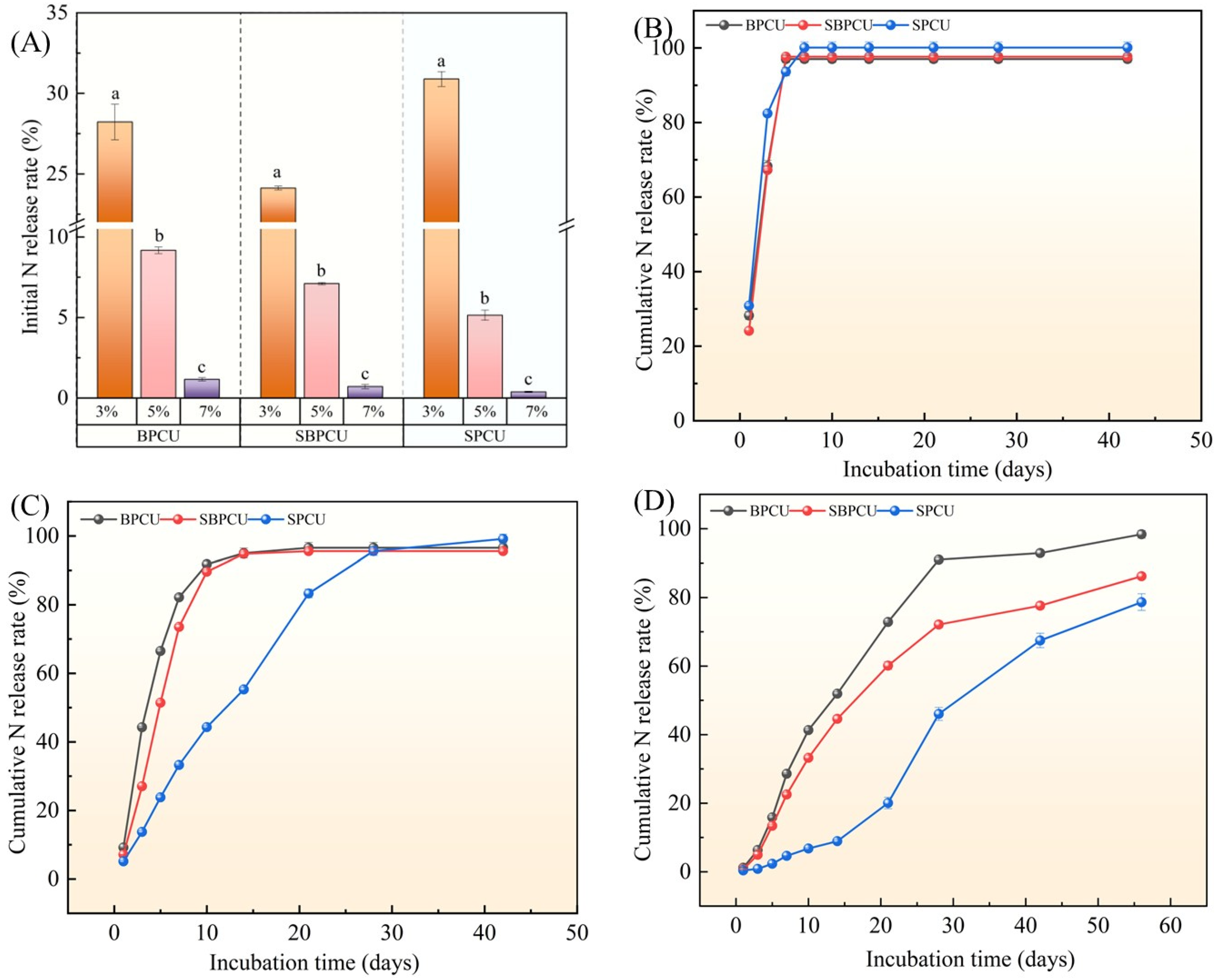

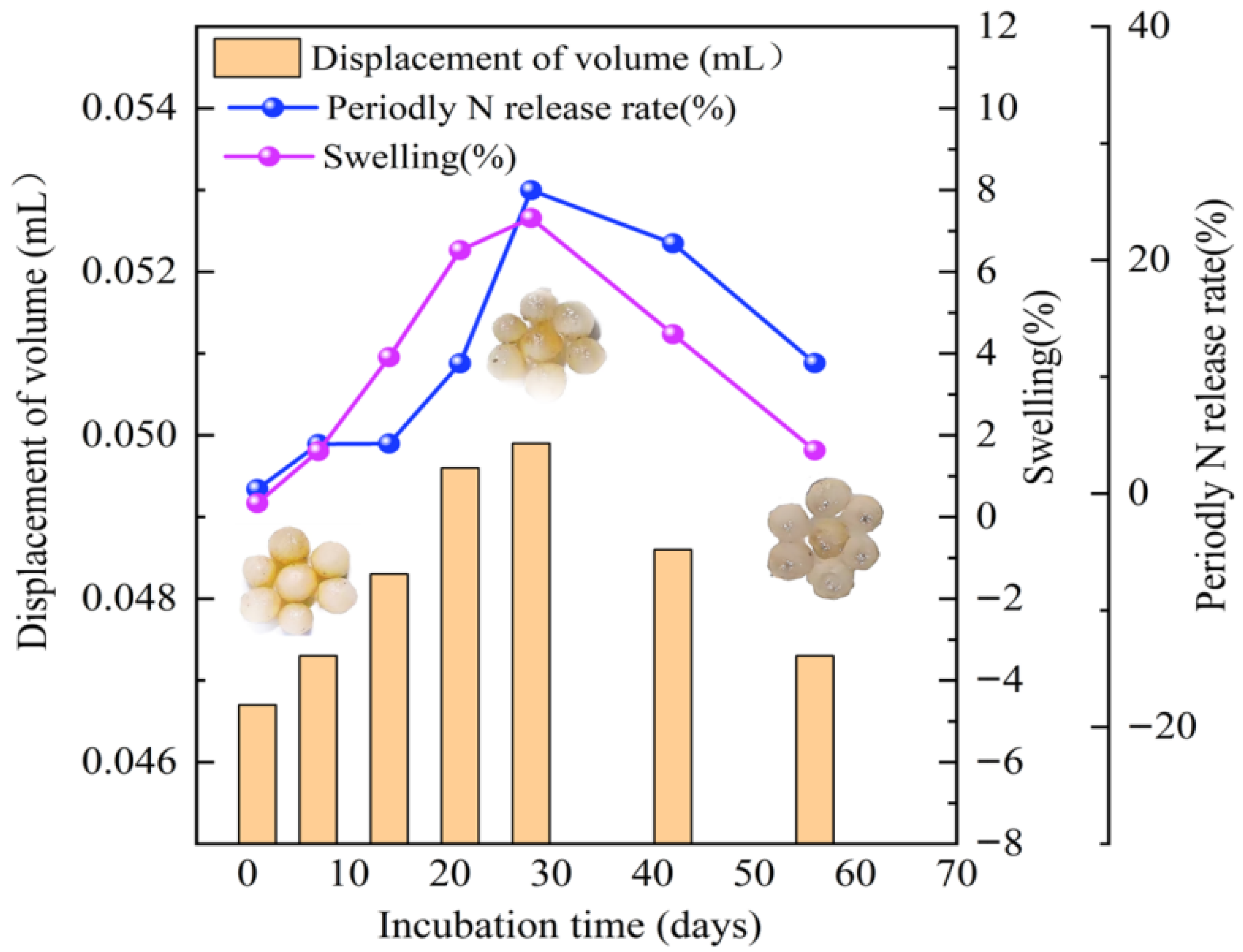

3.6. N-Release Behavior and Mechanism

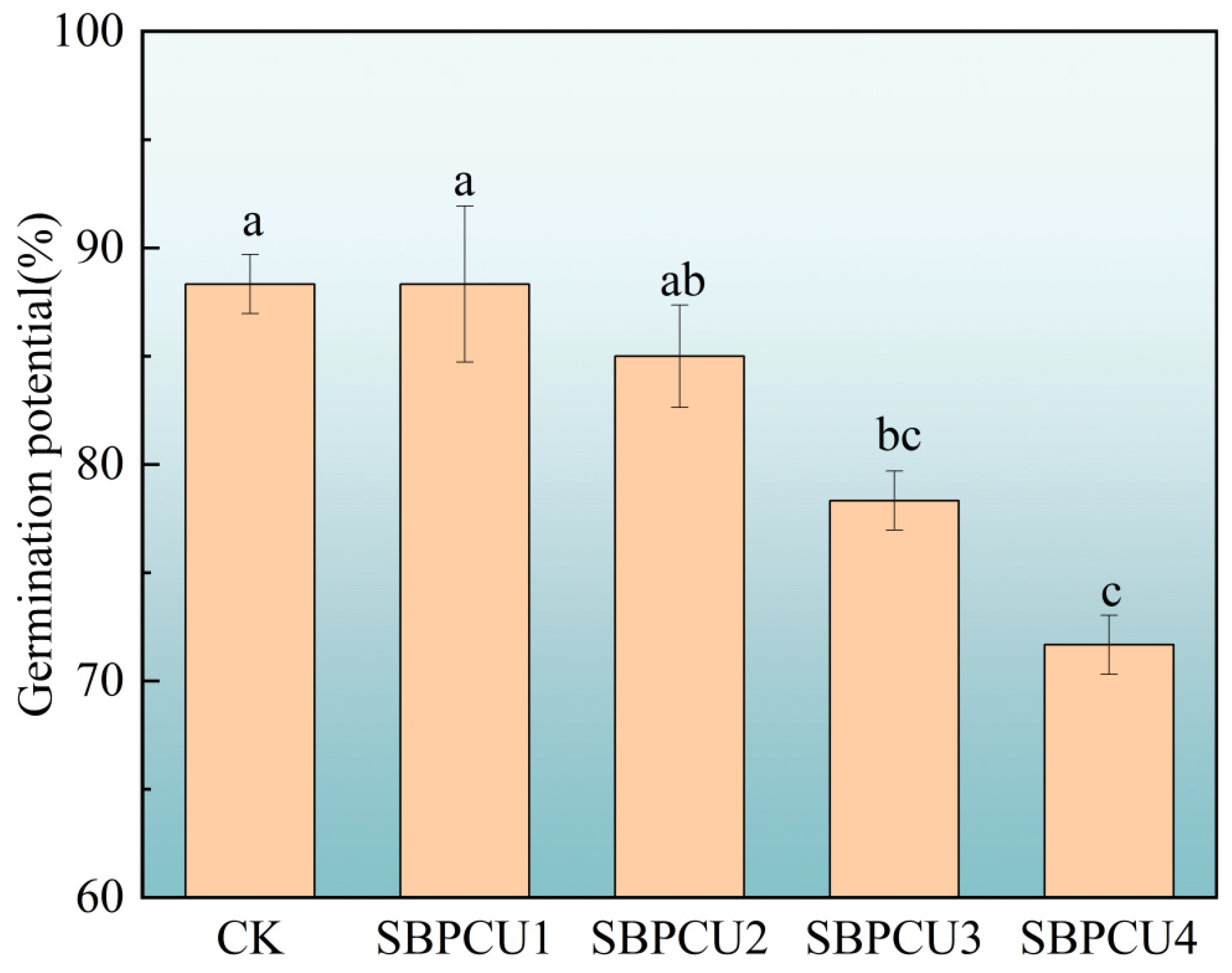

3.7. Influence of SBPCU Coating on Growth Parameters of Maize

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| SMS | Spent mushroom substrate |

| N | Nitrogen |

| PM200 | Polyphenyl polyisocyanate |

| PEG400 | Polyethylene glycol |

| BPCU | Bio-polymer-polyurethane-coated urea |

| NBPCU | Nano-modified bio-polymer-polyurethane-coated urea |

| SBPCU | Dual-modified bio-polymer-coated urea |

| SPCU | Castor-oil-based polyurethane-coated urea |

| SEM-EDX | Scanning electron microscope energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy system |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectrometer |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analyzer |

References

- Wang, C.; Song, S.; Du, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Zhou, C.; Li, P. Nutrient Controlled Release Performance of Bio-based Coated Fertilizer Enhanced by Synergistic Effects of Liquefied Starch and Siloxane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 236, 123994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Ma, F.; Yan, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Su, X.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xie, J. Double-modified Biopolymer-coatings Based on Recyclable Poplar-catkin: Efficient Performance, Controlled-release Mechanism and Rice Application. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 186, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Han, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhu, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zou, H. Hydrophobically Modified Water-based Polymer for Slow-release Urea Formulation. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 149, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Gao, L.; Tang, C.; Tong, Z.; Gao, B.; Meng, S.; Dong, S.; Zhang, L.; Ding, B.; Ren, P.; et al. Borate-epoxy Crosslinking Elastomer Modified Bio-based Polyurethane Coated Fertilizers with Toughness and Hydrophobicity. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Ge, C.; Ma, F.; Zhou, J.; Du, C. Biomimetic Modification of Waterborne Polymer Coating using Bio-wax for Enhancing Controlled Release Performance of Nutrient. Polymers 2025, 17, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermoesen, E.; Cordeels, E.; Schaubroeck, D.; Brosens, G.; Bodé, S.; Boeckx, P.; Van, V. Photo-crosslinkable Biodegradable Polymer Coating to Control Fertilizer Release. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 186, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Gao, H.; Zou, H.; Sun, D. Siloxane and Lauric Acid Copper Dual Modification Improves Hydrophobicity and Elasticity of all Biopolymer Coated Fertilizers with Enhanced Nitrogen Release Abilities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Zhao, W.; Chen, S. Smart Fertilizer with Temperature-Responsive Behavior Coated using a Naturally Derived Material. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Chen, D.; Xia, G.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Self-repairing Bio-based Controlled-release Fertilizer for Enhanced Quality and Nutrient Utilization Efficiency and Reveal their Healing Mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 504, 158852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channab, B.E.; Idrissi, A.E.; Zahouily, M.; Essamlali, Y.; White, J. Starch-based Controlled Release Fertilizers: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, E.; Sarkar, S.; Maji, P. A Review on Slow-release Fertilizer: Nutrient Release Mechanism and Agricultural Sustainability. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Yang, M.; Gao, B.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, D.; Shen, T.; Yao, Y.; Yang, Y. Ceresin Wax Enhances Hydrophobicity and Density of Bio-based Polyurethane of Controlled-release Fertilizers: Streamlined Production, Improved Nutrient Release Performance, and Reduced Cost. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Babapoor, A.; Ghanbarlou, S.; Kalashgarani, Y.M.; Salahshoori, I.; Seyfaee, A. Toward a New Generation of Fertilizers with the Approach of Controlled-release Fertilizers: A review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2024, 21, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Pang, M.; Li, H.; Zou, G.; Liang, L.; Li, L. Introduction of Bio-based Hard Segment as an Alternative Strategy to Environmentally Friendly Polyurethane Coated Urea. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 203, 117164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, K.; Mcquillan, R.; Stevens, G. Implementation of Biodegradable Liquid Marbles as a Novel Controlled Release Fertilizer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kassem, I.; Ablouh, E.; Bouchtaoui, F.; Jaouahar, M.; Achaby, M. Polymer Coated Slow/controlled Release Granular Fertilizers: Fundamentals and Research Trends. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 144, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.; An, L.; Zhang, S.; Feng, J.; Sun, D.; Yao, Y.; Shen, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M. The Long-term Effects of Microplastics on Soil Organomineral Complexes and Bacterial Communities from Controlled-release Fertilizer Residual Coating. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertahi, S.; Ilsouk, M.; Zeroual, Y.; Oukarroum, A.; Barakat, A. Recent Trends in Organic Coating Based on Biopolymers and Biomass for Controlled and Slow Release Fertilizers. J. Controll. Release 2021, 330, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Mao, Z. Degradation of Polyurethane Coating Materials from Liquefied Wheat Straw for Controlled Release Fertilizers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 44021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipponen, M.; Rojas, O.; Pihlajaniemi, V.; Lintinen, K.; Österberg, M. Calcium Chelation of Lignin from Pulping Spent Liquor for Water-resistant Slow-release Urea Fertilizer Systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; An, X.; Qian, X. Biodegradable and Reprocessable Cellulose-based Polyurethane Films for Bonding and Heat Dissipation in Transparent Electronic Devices. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 193, 116247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Cui, J.; Dong, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; et al. Self-healing Modified Liquefied Lignocellulosic Cross-linked Bio-based Polymer for Controlled-release Urea. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 186, 115241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Liang, H.; Quirino, R.; Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, C. Tunable Thermo-physical Performance of Castor Oil-based Polyurethanes with Tailored Release of Coated Fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 210, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wan, K.; Deng, C.; Pei, K. Preparation and Antibacterial Properties of SiO2 Encapsulated TiO2 Nanoparticles/cationic Waterborne Polyurethane Composite Coatings. Mater. Lett. 2025, 384, 138075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrencia, D.; Wong, S.; Low, D.; Goh, B.; Goh, J.; Ruktanonchai, U.; Soottitantawat, A.; Tang, S. Controlled Release Fertilizers: A Review on Coating Materials and Mechanism of Release. Plants 2021, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Tang, C.; Han, M.; Tong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, S. Tailoring MO-303 Reinforced Biopolymer Hybrid Coatings with Hierarchically Porous Architectures for Precision Nitrogen Delivery in Sustainable Agriculture. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2500185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Baharum, A.; Yu, L.; Yan, Z.; Badri, K. A Vegetable-oil-based Polyurethane Coating for Controlled Nutrient Release: A review. Coatings 2025, 15, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Xue, Y.; Wang, R.; Fan, X.; Sun, S. Green Construction and Release Mechanism of Lignin-based Double-layer Coated Urea. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Yang, M.; Han, Y. Hydrophobically Modified Sustainable Bio-based Polyurethane for Controllable Release of Coated Urea. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 14, 110114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Dun, C.; Hu, X.; Wang, R.; Cui, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H. Preparation of a Novel Economically Efficient and Environment Friendly Controlled Release Urea from Liquefied Corn Straw and Castor Oil. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, J.; Fan, H.; Li, R.; Shi, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, P. Preparation of Hydroxy-terminated Polydimethylsiloxane and Nano-SiO2 Hydrophobic Polyurethane Coated Urea and Investigation of Controlled Nitrogen Release. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 302, 120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Dun, C.; Jariwala, H.; Wang, R.; Cui, P.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Q.; Yang, S.; Zhang, S. Improvement of Bio-based Polyurethane and its Optimal Application in Controlled Release Fertilizer. J. Controll. Release 2022, 350, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamarpoor, R.; Jamshidi, M.; Joshaghani, M. Hydrophobic Silanes-modified Nano-SiO2 Reinforced Polyurethane Nanocoatings with Superior Scratch Resistance, Gloss Retention, and Metal Adhesion. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.; Marques, A.; Shakoor, R.; Montemor, M.; Taryba, M. Biopolyurethane Coatings with Silica-titania Microspheres (MICROSCAFS) as Functional Filler for Corrosion Protection. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Chen, R.; Li, R.; Yu, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Sun, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. Sustainable Bio-based Polyurethane Coating with Integrated Corrosion Resistance and Antifouling Functions. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 44, e01406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, S.; Chen, Q.; Chen, H.; Dong, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z. Lignin-Modified Petrochemical-source Polyester Polyurethane Enhances Nutrient Release Performance of Coated Urea. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Yang, M.; Gao, B.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, D.; Shen, T.; Yao, Y.; Yang, Y. Enhancing Longevity and Mechanisms of Controlled-release Fertilizers Through High Cross-link Density Hyperbranched Bio-based Polyurethane Coatings. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 18712–18724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, M.; Xiang, Z.; Zhou, Z. Enhancing the Slow-release Performance of Urea by Biochar Polyurethanes Co-coating. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2024, 22, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Cao, B.; Wang, X.; Liang, L.; Zou, G.; Yuan, L.; Chen, Y. Fully Bio-based Polyurethane Coating for Environmentally Friendly Controlled Release Fertilizer: Construction, Degradation Mechanism and Effect on Plant Growth. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Bio-based Materials for Fabrication of Controlled-release Coated Fertilizers to Enhance Soil Fertility: A Review. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Hu, L.; Lv, J.; Du, W. Self-assembled Superhydrophobic Bio-based Controlled Release Fertilizer: Fabrication, Membrane Properties, Release Characteristics and Mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, F.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Waterborne Polymer Coating Material Modified with Nano-SiO2 and Siloxane for Fabricating Environmentally Friendly Coated Urea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sha, G.; Cui, M.; Quan, M.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J. A Highly Reactive Soybean Oil-based Superhydrophobic Polyurethane Film with Long-lasting Antifouling and Abrasion Resistance. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 5663–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Sun, D. All-natural Plant-derived Polyurethane as a Substitute of a Petroleum-based Polymer Coating Material. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 6444–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Xie, J. Bio-based Elastic Polyurethane for Controlled-release Urea Fertilizer: Fabrication, Properties, Swelling and Nitrogen Release Characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Dong, S.; Zou, G.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Li, L. Study on Reduction Potential of Curing Agent in Sustainable Bio-based Controlled Release Coatings. Polym. Test. 2023, 127, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, S.; Lakshmi, D.; Vivekanandhan, S.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Biocarbons as Emerging and Sustainable Hydrophobic/oleophilic Sorbent Materials for Oil/water Separation. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 28, e00268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Xiang, Z.; He, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Luo, W.; Zhou, Z. Agricultural Sustainability: Biochar and Bio-based Polyurethane Coupling Coating to Prepare Novel Controlled-release Fertilizers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Balkovič, J.; Azevedo, L.; Skalský, R.; Bouwman, A.; Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Yu, C. Analyzing and Modelling the Effect of Long-term Fertilizer Management on Crop Yield and Soil Organic Carbon in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Superhydrophobic Controlled-release Fertilizers Coated with Bio-based Polymers with Organosilicon and Nano-silica Modifications. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 5, 19943–19953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Yang, L.; Xie, J.; Wang, T. Nutrient Diffusion Control of Fertilizer Granules Coated with a Gradient Hydrophobic Film. Colloids Surf. A 2020, 588, 124361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Yao, Y.; Xie, J.; Tang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M. Preparation and Nutrient Release Characteristics of Liquefied Apple Tree Branche-based Biocoated Large Tablet Urea. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 9775–9784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Pang, M.; He, W.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Li, L. Polyurethane-coated Urea Fertilizers Derived from Vegetable Oils: Research Status and Outlook. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 32626–32636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.; Wu, J.; Xiong, H.; Zeb, A.; Yang, T.; Su, X.; Su, L.; Liu, W. Impact of Polystyrene Nanoplastics (PSNPs) on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Richard Equation | First-Order Kinetic Equation | Quadratic Equation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | d | k | R2 | a | b | R2 | a | b | c | R2 | |

| BPCU-3% | 94.83 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 98.62 | 0.45 | 0.96 | 55.88 | 4.08 | 0.08 | 0.52 |

| BPCU-5% | 97.35 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 109.04 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 28.36 | 6.06 | 0.11 | 0.78 |

| BPCU-7% | 100.92 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 137.01 | 0.03 | 0.98 | −3.97 | 4.73 | 0.05 | 0.99 |

| SBPCU-3% | 97.63 | 16.22 | 7.80 | 1.00 | 101.86 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 53.79 | 4.35 | 0.08 | 0.52 |

| SBPCU-5% | 96.01 | 1.14 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 98.08 | 0.18 | 0.95 | 16.16 | 6.85 | 0.12 | 0.85 |

| SBPCU-7% | 84.03 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 193.57 | 0.01 | 0.93 | −2.74 | 3.74 | 0.04 | 0.99 |

| SPCU-3% | 98.03 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.79 | 104.30 | 0.45 | 0.96 | 60.98 | 3.87 | 0.07 | 0.51 |

| SPCU-5% | 114.38 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.99 | 125.62 | 0.04 | 0.99 | −1.59 | 5.40 | 0.07 | 1.00 |

| SPCI-7% | 163.88 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.97 | −9.12 | −0.04 | 0.81 | −0.59 | 1.56 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Treatment | Height (cm) | Stem Diameter (mm) | Root Length (cm) | Number of Lateral Roots | Root Fresh Weight (g) | Aboveground Fresh Weight (g) | Root Dry Weight (g) | Aboveground Dry Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 10.43 ± 0.18 b | 0.61 ± 0.01 bc | 9.27 ± 0.19 c | 8.33 ± 0.26 a | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | 0.63 ± 0.02 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 b |

| SBPCU1 | 11.30 ± 0.24 a | 0.70 ± 0.01 ab | 10.73 ± 0.19 a | 8.67 ± 0.27 a | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | 0.70 ± 0.02 a | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 0.21 ± 0.01 a |

| SBPCU2 | 10.63 ± 0.26 ab | 0.71 ± 0.03 a | 9.93 ± 0.35 ab | 8.33 ± 0.27 a | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | 0.66 ± 0.00 ab | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 0.22 ± 0.00 b |

| SBPCU3 | 10.20 ± 0.19 b | 0.65 ± 0.03 abc | 9.07 ± 0.15 c | 8.00 ± 0.47 a | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | 0.64 ± 0.01 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 0.20 ± 0.00 c |

| SBPCU4 | 10.10 ± 0.09 b | 0.59 ± 0.02 c | 8.93 ± 0.34 c | 8.00 ± 0.46 a | 0.08 ± 0.00 a | 0.62 ± 0.02 b | 0.010 ± 0.00 a | 0.19 ± 0.00 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Wu, H.; Huang, R. Siloxane and Nano-SiO2 Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Coatings Based on Recyclable Spent Mushroom Substrate: Excellent Performance, Controlled-Release Mechanism, and Effect on Plant Growth. Agriculture 2026, 16, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010076

Zhao J, Zhang Y, Liu F, Chen S, Wu H, Huang R. Siloxane and Nano-SiO2 Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Coatings Based on Recyclable Spent Mushroom Substrate: Excellent Performance, Controlled-Release Mechanism, and Effect on Plant Growth. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Jianrong, Yuanhao Zhang, Fuxin Liu, Songling Chen, Hongbao Wu, and Ruilin Huang. 2026. "Siloxane and Nano-SiO2 Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Coatings Based on Recyclable Spent Mushroom Substrate: Excellent Performance, Controlled-Release Mechanism, and Effect on Plant Growth" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010076

APA StyleZhao, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, F., Chen, S., Wu, H., & Huang, R. (2026). Siloxane and Nano-SiO2 Dual-Modified Bio-Polymer Coatings Based on Recyclable Spent Mushroom Substrate: Excellent Performance, Controlled-Release Mechanism, and Effect on Plant Growth. Agriculture, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010076