1. Introduction

Climate variability, increasing water scarcity, and market volatility have heightened the challenges that farmers face, particularly in drought-prone areas. In these conditions, farmers must make frequent, high-stakes decisions regarding crop selection, irrigation scheduling, and resource allocation, all while navigating significant uncertainty. These decisions are inherently quantitative, as they require the interpretation of measurements, the comparison of scenarios, and the projection of outcomes based on available data. Recent studies indicate that farmers are increasingly relying on numerical reasoning to make sense of sensor data, rainfall forecasts, and irrigation parameters in light of climatic variability [

1,

2]. Nonetheless, many farmers, particularly smallholders in resource-limited contexts, have few opportunities to develop the skills necessary to effectively engage with data-driven and smart farming systems.

Mathematical literacy is widely recognized as a critical competency for navigating complex, data-rich environments. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) defines it as the ability to formulate, employ, and interpret mathematics in real-world contexts, enabling individuals to reason mathematically and make informed judgments [

3]. Beyond formal education, mathematical literacy is essential in practical fields where quantitative reasoning supports everyday decisions, such as agriculture. In drought-prone farming systems, it enhances farmers’ ability to interpret measurements, assess risks, and adapt management strategies under changing conditions.

From an educational perspective, the development of mathematical literacy closely aligns with the principles of Realistic Mathematics Education (RME). RME emphasizes that learning should stem from meaningful real-world contexts, enabling learners to gradually organize, formalize, and abstract mathematical ideas through problem-solving activities [

4,

5]. Empirical research has shown that contextualized mathematical tasks enhance learners’ abilities to interpret, represent, and communicate quantitative information [

6,

7]. These results are consistent with extensive evidence suggesting that technology-enhanced learning environments impact cognitive and emotional processes prior to affecting educational outcomes [

8,

9]. Nonetheless, much of the existing RME-based research has concentrated on school-aged learners, with relatively little attention given to adult learners in community or occupational settings.

In parallel, a growing body of research has explored the role of STEM and context-based learning in fostering problem-solving, systems thinking, and sustainability awareness. Studies in agricultural and STEM education suggest that authentic agricultural tasks offer rich opportunities to apply mathematical and scientific concepts to real-world problems [

10,

11,

12]. However, these initiatives are often embedded within formal educational settings and typically target secondary or tertiary students [

13]. As a result, farmers and community learners, who regularly make critical decisions related to water use, input management, and production risk, remain underrepresented in the literature on contextualized learning and literacy development.

The expansion of smart agriculture and the Internet of Things (IoT) has fundamentally transformed decision-making processes within modern farming systems. Through the integration of sensor networks, automated irrigation systems, and sophisticated data analytics, smart agriculture provides farmers with real-time information on soil moisture, microclimatic conditions, and crop status, enabling more precise and adaptive management practices [

9,

14,

15]. Nevertheless, the effective use of these technologies depends on farmers’ abilities to interpret graphical data, understand sensor outputs, and translate numerical information into practical management actions [

16]. Reviews of digital agriculture adoption consistently accentuate that mathematical and data literacy are critical prerequisites for enabling farmers to progress from passive technology users to informed, data-driven decision makers, thereby enhancing productivity, sustainability, and resilience in the face of ongoing agricultural challenges [

17,

18,

19].

In the Thai context, New Theory Agriculture (NT) is rooted in the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy. NT provides a unique framework for managing land and water amid environmental uncertainty. It advocates for the division of farmland into zones designated for water storage, rice cultivation, mixed crops, and residential use. This approach aims to enhance self-reliance and sustainability among farmers [

20]. Those implementing NT must utilize quantitative reasoning, including proportional thinking, water budgeting, seasonal variation, and risk management [

21]. Research indicates that NT enhances community resilience in drought-prone areas by fostering diverse crop production and adaptive water management strategies [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Therefore, NT functions as both a management strategy and a framework that supports the application of mathematical reasoning in practice.

Overall, these research strands indicate a promising yet underexplored connection between mathematical literacy, smart agriculture, and frameworks such as NT. Previous studies primarily focused on mathematical literacy within school settings [

3,

7] and concentrated on economic or adoption outcomes in digital agriculture [

15,

18]. There is limited understanding of how adults in communities develop mathematical literacy and data-driven decision-making skills through everyday agricultural practices. In addition, there is a lack of empirical research on how smart agriculture technologies, when integrated within systems such as NT, function as educational environments for communities.

This study investigates the interplay of NT and Smart Agriculture (SA) in enhancing mathematical literacy, data-driven decision-making, and community learning among farmers in drought-prone areas. Drawing on Realistic Mathematics Education, STEM education, and data literacy, it presents a structural model connecting New Theory Agriculture (NT), Smart Agriculture (SA), Mathematical Literacy (ML), Data-Driven Decision-Making (DD), and Community Learning Outcomes (CL). Specifically, it aims to: (1) analyze NT’s effect on SA adoption and ML; (2) examine how ML shapes DD; and (3) clarify the pathways through which these factors jointly and individually affect CL.

This conceptual framework yields eight hypotheses (H1–H8) regarding the links among NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL. These hypotheses cover direct effects and mediated pathways. They offer a clear theoretical basis for the analyses in the following sections.

2. Materials and Methods

The development of the measurement instruments adhered to established guidelines for scale construction in behavioral and educational research.

Table 1 provides an overview of the constructs, including the number of items per construct and representative sample items. For brevity, only representative sample items are presented below. All procedures for instrument development and validation were conducted in compliance with ethical research standards and received approval from the Ethics in Human Research Committee of Rajamangala University of Technology Suvarnabhumi (IRB-RUS-2025-008).

2.1. Research Design

The research design used quantitative methods to examine NT and SA relationships with ML and DD and their impact on CL, using self-reported questionnaire data. The researchers used covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) to test their proposed conceptual framework, which assessed both measurement and structural model components at once.

Data were collected from rice farmers participating in large-scale farming communities, and the unit of analysis was the individual farmer. The research design proved suitable for testing theoretical predictions while studying intricate relationships among hidden variables in an agricultural setting with community learning environments.

2.2. Measures

Five latent constructs were measured in this study: NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL. Each construct was operationalized as a multi-item scale using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Item development followed established guidelines in behavioral and educational research, including expert content validation, iterative refinement, and pilot testing [

7,

29].

2.2.1. New Theory Agriculture (NT)

In this study, NT is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct comprising three core components. These components reflect both its function as a farming system and its role as a contextual learning framework.

Systematic Resource Allocation (NT1) refers to the planned allocation of land and resources based on proportional principles. This component emphasizes estimating land capacity, calculating allocation ratios, and optimizing the use of farming space. Such practices require quantitative reasoning and support farmers’ engagement with numerical thinking in everyday agricultural activities [

20].

Water and Risk Management (NT2) focuses on monitoring rainfall patterns, calculating water requirements, preparing for drought cycles, and evaluating production risks. These activities are closely aligned with established risk-management approaches in climate-sensitive agricultural systems and require interpreting quantitative and environmental data [

24,

33].

Community Cooperation and Collective Action (NT3) encompasses shared water management, cooperative farming groups, and collective learning practices. This component highlights the social dimension of NT, in which collaboration and knowledge exchange enhance information flow, adaptive capacity, and community resilience under changing climatic conditions [

26,

31].

For brevity, only representative sample items are presented below.

“I plan the use of farmland by dividing areas for water storage, rice cultivation, and other crops.”

2.2.2. Smart Agriculture (SA)

SA is the use of digital tools, such as sensors, IoT, data analysis, automation, and remote sensing, in farming. The goal is to make farming more efficient, precise, and eco-friendly. The idea stems from Agriculture 4.0, which emphasizes connectivity, smart farm management, and data-driven decision-making [

15].

SA aims to provide farmers with accurate real-time information on soil conditions, crop status, water requirements, and climatic variability. This enables more precise interventions and reduces production risks, especially in drought-prone contexts. Previous studies have shown that the benefits of SA go beyond technology adoption and depend on the cognitive engagement needed to interpret sensor outputs, analyze indicators, and adjust farm management practices [

14,

18]. Such activities require mathematical reasoning, comparative evaluation, and forecasting. As a result, SA fits within broader perspectives of data literacy and technology-enhanced learning [

29].

In this context, the present study identifies and examines three key components that operate SA.

Digital Sensing and Monitoring (SA1) includes soil moisture sensors, water-level meters, weather stations, and crop health imaging systems. These tools generate high-frequency data, which are essential for optimizing irrigation, fertilizer application, and drought response [

16].

Data Analytics and Decision-Support Systems (SA2) transform sensor data into actionable insights. This occurs through dashboards, mobile applications, and predictive models. This component strengthens farmers’ data interpretation skills and supports evidence-based decision-making [

34].

Automation and Smart Control (SA3) involves automatic irrigation systems, drone-assisted monitoring, and actuator-based environmental control technologies. These systems reduce labor demands and enable timely responses to environmental changes [

27].

Together, these components position SA as both a technological innovation and a learning-oriented ecosystem. SA encourages farmers to engage with quantitative information, develop mathematical and data literacy, and enhance their adaptive capacity in the face of climatic uncertainty. Accordingly, this study conceptualizes SA as a central mechanism supporting the development of mathematical literacy and data-driven decision-making in communities repeatedly affected by drought.

For brevity, only representative sample items are presented below.

“I use digital tools or sensors to monitor soil moisture or water levels.”

2.2.3. Mathematical Literacy (ML)

ML refers to the capacity to apply mathematical knowledge, reasoning, and representation to understand and address problems encountered in everyday contexts. According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), ML involves the ability to formulate, employ, and interpret mathematics in ways that support reasoning, judgment, and informed action in real-world situations [

3]. From an educational perspective, the development of ML aligns closely with the principles of Realistic Mathematics Education (RME), which emphasize learning mathematics through meaningful, context-rich activities rather than through abstract procedures alone [

4,

7]

In places where farming depends on rain, being good at math helps farmers manage their farms well. Farmers often need to estimate how much water crops need, plan when to water, guess how much they will harvest, figure out costs, and read information from smart farm tools [

35,

36]. Doing these things uses math skills and helps build ML during hands-on farm work, not just in a classroom.

In this study, mathematical literacy is seen as a set of thinking and math skills, not as decision-making in itself. ML helps farmers understand and use numbers, but using this data to make choices on the farm is called DD. Separating these ideas makes the model clearer by showing that ML supports, but does not replace, decision-making.

To help with testing, ML in this study is divided into four parts:

Interpretation and Representation (ML1) means being able to read graphs, understand numbers, and turn real problems into math questions or simple math ideas. This skill is important in math tests like the PISA [

3].

Mathematical Reasoning (ML2) involves finding links, comparing amounts, making logical arguments, and considering different options. This idea aligns with RME’s focus on reasoning through real-life situations [

4].

Problem Solving and Modeling (ML3) means making mathematical models for real problems, such as droughts, and choosing effective ways to solve them. It also includes checking the answers. Modeling is a fundamental part of using math in real life [

28].

Application of Mathematical Reasoning to Practical Contexts (ML4) is the transfer of mathematical insights to practical situations, such as interpreting the quantitative implications of irrigation schedules, water allocation ratios, or cost structures. This component emphasizes cognitive application and transfer. It maintains a clear boundary between ML and the behavioral act of decision implementation, rather than conflating the two [

29].

In summary, these four components collectively position ML as a key cognitive link between engagement with smart agriculture technologies and broader learning processes. By enabling individuals to interpret data, reason quantitatively, and model practical challenges, ML supports subsequent DD and contributes to community-level learning outcomes in drought-prone agricultural contexts.

For brevity, only representative sample items are presented below.

“I can read and understand graphs related to irrigation or weather conditions.”

2.2.4. Data-Driven Decision-Making (DD)

DD refers to the systematic process by which individuals apply data and analytical outputs to guide professional decisions. Unlike mathematical literacy, which emphasizes the cognitive ability to understand and interpret quantitative information, DD focuses on the behavioral process of using data as evidence to inform and justify actions.

DD is commonly conceptualized as a multi-stage process that begins with data collection, followed by data interpretation and analysis, and culminates in decision implementation aimed at improving accuracy, performance, and operational efficiency. Empirical research in educational and organizational contexts demonstrates that data-driven decision-making enhances judgment quality and leads to more effective outcomes when decisions are grounded in evidence rather than intuition alone [

29,

30].

In agricultural systems, particularly in drought-prone regions, DD plays a critical role in managing climate variability, water availability, and soil moisture fluctuations. Smart Agriculture (SA) technologies enable farmers to access continuous data streams from soil sensors, weather stations, and digital monitoring tools. These technologies support farmers in tracking field conditions, identifying patterns, forecasting irrigation requirements, and selecting appropriate management strategies in response to environmental uncertainty [

14,

15].

Previous studies indicate that farmers who actively employ data-driven decision-making achieve more timely and precise management decisions, thereby reducing production risks and improving environmental sustainability [

18]. In this study, DD is defined as a behavioral decision-making process through which the use of smart agricultural technologies supports learning and adaptation at the community level [

37].

Accordingly, DD is operationalized as a multidimensional construct comprising three interrelated components [

38].

Data Interpretation (DD1) refers to the ability to read and comprehend numerical information, graphs, sensor outputs, and environmental data, transforming raw data into meaningful insights that inform irrigation planning, input management, and drought response [

29].

Analytical Reasoning (DD2) involves evaluating alternative courses of action, identifying trends, assessing risks, and formulating logical conclusions based on quantitative evidence, as emphasized in evidence-based decision science [

30].

Decision Implementation (DD3) refers to translating data-based insights into concrete farm management actions, such as adjusting irrigation schedules, modifying crop plans, or implementing adaptive measures in response to drought forecasts. This component also includes monitoring outcomes and refining decisions over time, reflecting the iterative and adaptive nature of DD in dynamic agricultural environments [

16].

Together, these components position DD as an iterative process through which farmers convert information from smart agriculture technologies into adaptive actions. Integrating interpretation, analysis, implementation, and feedback, DD supports sustainable farm management and strengthens community resilience in drought-affected systems [

39].

For brevity, only representative sample items are presented below.

“I use data from sensors or records to support farming decisions.”

2.2.5. Community Learning Outcomes (CL)

CL are the skills, actions, and knowledge developed through collaborative learning and problem-solving. CL draws from social learning theory [

40] and community-based learning, demonstrating that learning extends beyond the individual mind and is shaped through collective experience and engagement with real-world challenges [

26].

In drought-prone agricultural contexts, community learning plays a critical role. It enables farmers to collectively manage resources, interpret data, and respond to climatic variability [

41]. Prior research indicates that communities with strong learning processes show greater resilience, more effective information exchange, and higher adaptive capacity when facing environmental stressors [

24,

31]. When smart agriculture technologies and data-driven practices are integrated into farming systems, community learning outcomes reflect not only shared knowledge but also the development of collective reasoning and coordinated decision-making [

39].

In this study, CL refers to the combined effects of NT, math skills, and the use of data to make group decisions. We measure CL with four connected parts.

Knowledge Sharing (CL1) occurs when community members share their experiences, farming practices, thoughts on sensor data, and approaches to handling drought. This sharing is a key way for the community to learn and change [

26].

Collaborative Problem-Solving (CL2) is when people work together to spot problems, generate solutions, and solve them as a group. Research shows teamwork like this makes communities stronger [

31].

Adaptive Capacity (CL3) is the community’s ability to adapt farming practices when weather changes or new tools become available. Communities with strong adaptive capacity can manage change and recover from weather-related problems [

24].

Collective Decision-Making (CL4) involves people planning and working together on issues such as water use, crop selection, resource management, and risk reduction. This aligns with important ideas about managing community resources collaboratively [

32].

All together, these parts show CL as the result of shared understanding, collaboration, and adaptation to change [

42]. In farming communities that often face drought, CL helps turn shared experience and information into collective actions. This makes the community stronger and better able to keep going in the long run.

For brevity, only representative sample items are presented below.

“Farmers in my community share farming knowledge and data.”

To provide an overview of the measurement framework used in this study,

Table 1 summarizes the key constructs, their measurement dimensions, item codes, number of items, brief descriptions, and the theoretical sources informing instrument development.

2.2.6. Content Validity and Expert Review

Content validity was evaluated by three experts, each with specialized backgrounds in mathematics education, agricultural systems, or measurement evaluation. Although some methodological guidelines recommend larger expert panels, interdisciplinary research frequently prioritizes the depth and relevance of expertise over panel size, and previous studies have demonstrated that a panel of three experts is often sufficient for robust content validation in such contexts.

The Item–Objective Congruence (IOC) scores for all items ranged from 0.80 to 1.00, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold and indicating strong alignment between the items and their intended constructs. The experts provided detailed feedback that led to substantive revisions, including clarification of item wording and enhanced contextualization of mathematical literacy (ML) and data-driven decision-making (DD) items for farming applications. Even though inter-rater agreement statistics such as Fleiss’ kappa were not calculated, given that the review process emphasized conceptual relevance and the alignment of items with objectives rather than consistency in ratings, the use of the IOC method was appropriate for this stage of instrument development, ensuring both content clarity and contextual fit.

2.2.7. Pilot Testing

A pilot study was conducted with 30 farmers from a drought-prone district. Its purpose was to support the adequacy of the measurement instruments prior to large-scale data collection. The pilot tested item clarity, contextual appropriateness, and response variability. All items were clear, suitable for the target population, and showed sufficient variance. Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeded 0.82 for all constructs.

Because the pilot study had a limited sample size, factor-analytic techniques such as exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis were not conducted at this stage, as stable factor structure evaluation requires larger samples. Therefore, construct validity and factorial structure were rigorously examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the full study sample (N = 320), following established guidelines for structural equation modeling. The pilot reliability evidence and expert-based content validation together provide convergent support for the reliability and measurement quality of the study instruments.

2.3. Participants

The participants comprised 320 rice farmers from large-scale farming communities in Thailand’s drought-prone regions. Eligible participants were required to be actively engaged in rice farming and involved in farm-level decision-making. The unit of analysis was an individual farmer.

In this study, the inclusion criterion for SA technologies is the availability of SA-related infrastructure at the community level (e.g., sensors, digital monitoring systems, or shared smart irrigation tools), meaning these technologies are present and accessible but not necessarily used by every individual. Active, individual-level use of SA technologies was assessed separately through the questionnaire. Therefore, the sample includes farmers in communities where SA technologies are available but may not yet be actively used. This distinction between technology availability and active use is taken into account when interpreting SA’s role as a learning and decision-support mechanism.

A multi-stage sampling procedure was employed. In the first stage, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province was purposively selected for its recurrent drought conditions and for the widespread implementation of NT practices supported by SA initiatives. The province consists of 16 districts; one sub-district was selected from each district based on documented drought exposure, active large-scale rice farming, and the presence of SA technologies such as soil moisture sensors, digital monitoring systems, or water management tools supported by local agricultural agencies.

In the second stage, in collaboration with local agricultural extension officers, two farming communities were selected from each sub-district, for a total of 32 communities. These officers assisted in identifying communities where NT principles and SA technologies were actively practiced. In the final stage, individual farmers were then recruited from each community based on the eligibility criteria.

A total of 350 questionnaires were distributed in the selected communities. Of these, 320 were returned and suitable for analysis, giving a 91.4% response rate.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

The research team collected data in three phases over four months to ensure accuracy, relevance, and rigor.

In the first phase, the team visited drought-prone sub-districts of Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province to begin the project. During this initial stage, the focus was on building rapport with community members and obtaining approval from local leaders and farm advisors. Preliminary assessments at this phase confirmed the use of NT and SA in each community. Following these steps, the team used direct observations and informal conversations to understand local practices, which also helped refine survey wording for clarity and accessibility across literacy levels.

In the second phase, trained research assistants administered questionnaires to eligible participants using both self-administered paper formats and interview-assisted protocols to accommodate varying literacy levels. In interview-assisted sessions, assistants read items aloud neutrally and clarified only vocabulary or farming terms, without interpretive guidance. Technical language was replaced with practical descriptions for mathematical concepts. This approach ensured responses reflected actual farming practices and understanding, not reading or test-taking skills. Participants were informed of objectives, confidentiality, and voluntary participation; all provided written consent. No incentives were offered.

In the third phase, the team conducted follow-up conversations with 30 participants. The goal was to better understand how they used SA tools such as sensors, dashboards, and digital systems. Discussions focused on how participants used and interpreted digital data in their farming decisions. These qualitative findings helped interpret quantitative results but were not used for structural analysis. The team checked each questionnaire for completeness and assigned coded IDs to anonymize responses before data entry and analysis. The institutional review board approved the study, and all procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5. Data Analysis

A two-stage data analysis procedure was employed to ensure methodological rigor. In the first stage, CFA was used to evaluate the measurement model. This assessment examined factor loadings, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Model fit was evaluated using several indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

Building upon the results from the first stage, the second stage involved conducting Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), a statistical technique used to examine complex relationships among unobserved, or ‘latent,’ variables. SEM enabled the estimation of direct, indirect, and total effects, where direct effects refer to the immediate relationships between variables, and indirect effects involve the influence of one variable on another through one or more intervening variables within the proposed model. The strength and explanatory power of the relationships were assessed using standardized path coefficients (which measure the strength of the relationships between variables on a standardized scale) and coefficients of determination (R2), which indicate how much variance in the dependent variable is explained by the model.

To further support the methodological approach, a post hoc power analysis (an analysis conducted after data collection to determine whether the study had sufficient participants to reliably detect statistical effects) was conducted to assess the adequacy of the sample size for SEM (structural equation modeling). Following the guidelines of Hair et al. [

43], a minimum sample size of approximately 200 is considered sufficient for SEM models of moderate complexity. With a final sample of 320 participants, the study exceeds this recommendation and provides adequate statistical power to detect medium effect sizes (β ≥ 0.20) at the 0.05 significance level.

In summary, the two-stage analytical approach improved the accuracy, validity, and interpretability of the study findings. This was achieved by ensuring robust evaluation of both the measurement and structural models. In addition, a post hoc power analysis assessed the adequacy of the sample size for structural equation modeling. With a total sample of 320 respondents, the analysis showed sufficient statistical power (exceeding 0.80). This was enough to detect medium-sized effects among latent constructs, consistent with established methodological recommendations for SEM in behavioral and educational research [

43].

2.5.1. Preliminary Screening and Assumptions

CFA, a statistical technique used to verify the factor structure of observed variables, was conducted after completing the initial screening of the dataset. Missing data accounted for less than 2% of responses across the entire survey. Given this minimal level of missingness, missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation within the SEM framework. FIML is a method for handling missing data that enables unbiased parameter estimation under the missing-at-random (MAR) assumption (i.e., the probability of missingness depends only on observed data, not unobserved data), without requiring explicit data imputation [

44].

Data normality was assessed by examining skewness (a measure of symmetry) and kurtosis (a measure of peakedness), which remained within acceptable thresholds (|skewness| < 2 and |kurtosis| < 7), indicating no substantial deviation from normality [

45,

46]. Multicollinearity, or when predictor variables are highly correlated, was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIF), a diagnostic statistic; all values were below 3.0, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a concern in the analysis [

43].

2.5.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

CFA was conducted to evaluate the measurement model and to validate the five latent constructs: NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL. CFA provided an assessment of how well the observed variables represented their underlying latent constructs and was performed in accordance with established guidelines for SEM.

Model fit was assessed using several indices, following [

45,

47]. Criteria included χ

2/df less than 3.00, CFI of 0.95 or higher, RMSEA of 0.06 or lower, and SRMR of 0.08 or lower. GFI and AGFI values of 0.90 or above also indicated acceptable fit, as suggested by Jöreskog and Sörbom [

48].

Convergent validity was evaluated using three criteria: standardized factor loadings above 0.70, Composite Reliability (CR) of at least 0.70, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of 0.50 or higher. These indicate adequate item–construct consistency and reliability [

43].

Discriminant validity was checked by confirming that each construct’s AVE square root exceeded its correlations with other constructs. This indicated each latent variable was empirically distinct [

49].

Overall, the CFA results indicated that the measurement model was satisfactory for further structural analysis.

2.5.3. Structural Equation Modeling Procedures

After establishing the validity and reliability of the measurement model, SEM was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships among the latent constructs. SEM was selected because it enables the simultaneous estimation of multiple relationships while accounting for measurement error, making it particularly suitable for theory-driven models in educational and behavioral research [

43,

45].

The structural model was estimated to test the direct, indirect, and total effects specified in the theoretical framework. Path coefficients were examined to evaluate the strength and direction of the hypothesized relationships, with statistical significance assessed at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, following conventional standards in statistical analysis.

Model fit was reassessed after including structural paths using the same fit indices applied in the CFA. These included the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ

2/df), CFI, GFI, AGFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. This procedure ensured the structural model maintained an acceptable level of fit after adding the hypothesized relationships [

47].

To interpret the magnitude of the modeled relationships, standardized path coefficients (β) were used, following the guidelines proposed by Hair et al. [

43] for SEM. In this context, standardized coefficients around 0.20 were interpreted as small to moderate effects, coefficients around 0.30 as moderate effects, and coefficients of 0.40 or higher as substantial effects within behavioral and educational research.

The explanatory power of the structural model was further evaluated with R2. These indicate the proportion of variance in each endogenous construct explained by its predictors. Indirect and total effects among NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL were also examined. This assessed the mediating mechanisms proposed in the model. Overall, the SEM results provided empirical support for the theoretically grounded relationships specified in the study.

2.5.4. Additional Diagnostics

SEM was conducted using the lavaan engine implemented in Jamovi (version 2.6.26). Model parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator. This estimation method is appropriate given the adequate sample size and the acceptable distributional properties of the observed variables, as indicated by skewness and kurtosis values within recommended thresholds [

45,

46].

To further strengthen the evaluation of mediation effects, standard errors and confidence intervals for indirect effects were obtained using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples, providing robust estimates.

Table 2 summarizes the data analysis procedures applied at each stage of the study, including the analytical steps, statistical techniques, software used, and the rationale for each methodological choice.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 3 presents the demographic characteristics of the study participants. The sample primarily included middle-aged rice farmers with substantial experience. Most took part in farm-level decision-making. Many reported repeated exposure to drought and had prior experience with NT practices and SA technologies. The profile reflects the study’s focus on large agricultural communities in drought-prone regions, where adaptive decisions and technology-supported farming are critical.

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

Detailed descriptive statistics for all observed variables are presented in

Table 4. These include means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis values. The results confirm adequate variability across all measurement items, with mean scores ranging from 3.21 to 4.36 and standard deviations ranging from 0.62 to 0.91. No severe outliers were detected, and the distribution of responses satisfied the assumptions required for maximum likelihood estimation, as skewness values were below 2 and absolute kurtosis values were below 7.

Missing data accounted for less than 2% of the total responses. Given this minimal level of missingness, we handled missing values using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. This method provides unbiased parameter estimates under the missing-at-random assumption and circumvents the need for explicit data imputation.

To evaluate multicollinearity, we used variance inflation factors (VIF), all of which were below 2.50. This result indicates that multicollinearity was not a concern in the analysis.

3.3. Assessment of Common Method Bias (Harman’s Single-Factor Test)

Because data were collected using self-reported questionnaires, common method bias (CMB) was assessed with Harman’s single-factor test, as recommended by Podsakoff et al. [

50]. All items from the five constructs NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL were included in an exploratory factor analysis without rotation.

The analysis produced several factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. The first unrotated factor explained 32.6% of the total variance, which is below the common 50% threshold. Thus, no single factor dominated the item covariance.

Therefore, Harman’s single-factor test suggests that common method bias is unlikely to seriously affect this study or its interpretation of structural relationships.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 5 shows descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL. All constructs have mean values above the midpoint of the five-point Likert scale, indicating generally positive participant perceptions.

The analysis revealed all constructs are moderately to strongly positively associated, with correlation coefficients from r = 0.55 to r = 0.69. DD showed the strongest correlation with CL (r = 0.69), highlighting a close link between data-informed decisions and collective learning.

The correlation pattern aligns with the proposed theoretical framework and provides preliminary support for the relationships analyzed using structural equation modeling.

3.5. Measurement Model

3.5.1. Factor Loadings and Convergent Validity

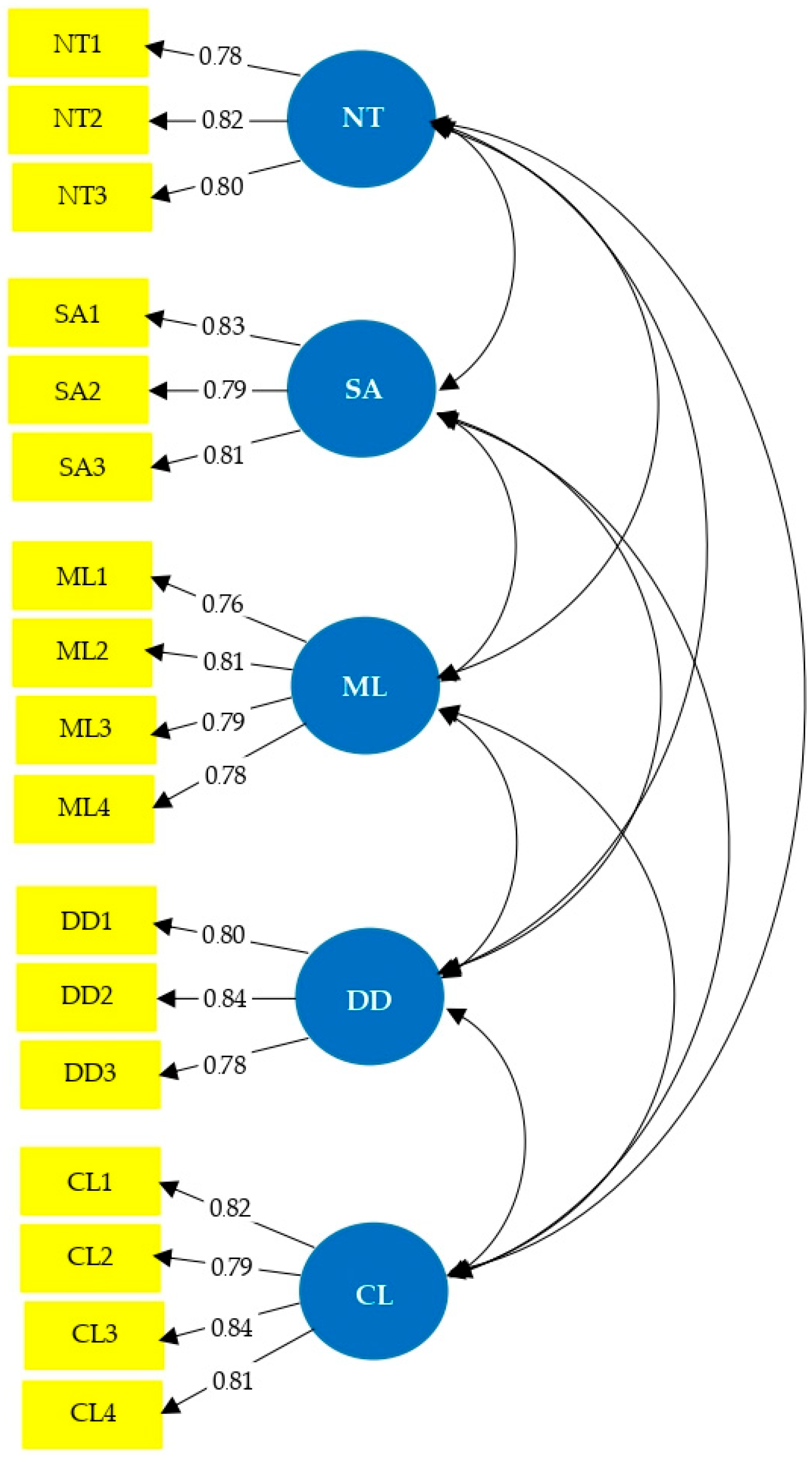

The measurement model was evaluated to assess both reliability and validity. As reported in

Table 6, all constructs demonstrated satisfactory convergent validity and internal consistency, as indicated by standardized factor loadings, CR, and AVE.

Figure 1 illustrates the measurement model, showing the relationships between the latent constructs and their observed indicators.

Standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.76 to 0.84. These values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 for indicator reliability. Squared factor loadings ranged from 0.58 to 0.71. Each indicator accounted for more than half of the variance in its corresponding latent construct. Error variances ranged from 0.29 to 0.42, suggesting low levels of measurement error.

Internal consistency reliability was strong across all constructs. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.82 to 0.86, exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.70 [

51]. CR values ranged from 0.85 to 0.89, further confirming the scales’ reliability. Convergent validity was supported by AVE values ranging from 0.64 to 0.66, all above the minimum threshold of 0.50 recommended by Fornell and Larcker [

49].

The overall measurement model showed a good fit. Fit indices indicated acceptable model fit: χ

2/df = 1.57 (<3.00), CFI = 0.964 (>0.95), GFI = 0.925 (>0.90), AGFI = 0.903 (>0.90), RMSEA = 0.041 (<0.06), and SRMR = 0.039 (<0.08). All these values fell within the recommended ranges reported by Hu and Bentler [

47].

Overall, these results show that the measurement model is reliable and valid, making it suitable for structural equation modeling, as detailed in the indicator-level statistics reported in

Table 6.

3.5.2. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [

49]. The results demonstrated strong discriminant validity across all constructs, as shown in

Table 7. The square root of the AVE (√AVE) for each latent construct was as follows: NT = 0.80, SA = 0.81, ML = 0.80, DD = 0.81, and CL = 0.81. For each construct, the √AVE exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations.

NT’s √AVE (0.80) exceeded its correlations with SA (0.62), ML (0.58), DD (0.55), and CL (0.60). SA, ML, DD, and CL also showed the same pattern. This suggests that each construct accounts for more variance among its own indicators than among those of the others.

According to [

49], discriminant validity is established when the square root of each construct’s AVE, a measure of the amount of variance captured by a construct, is greater than its correlations with other constructs. The results confirm that ML, DD, and CL are empirically distinct. They do not exhibit conceptual overlap. These findings indicate that the measurement model satisfies the discriminant validity requirements for later structural equation modeling, a statistical technique for analyzing structural relationships.

To assess discriminant validity, we examined the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio as recommended by Hair et al. [

43]. As reported in

Table 8, all HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, including the ML–DD pair (HTMT = 0.82). These results provide additional evidence that the constructs, while theoretically related, represent distinct conceptual domains.

3.6. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

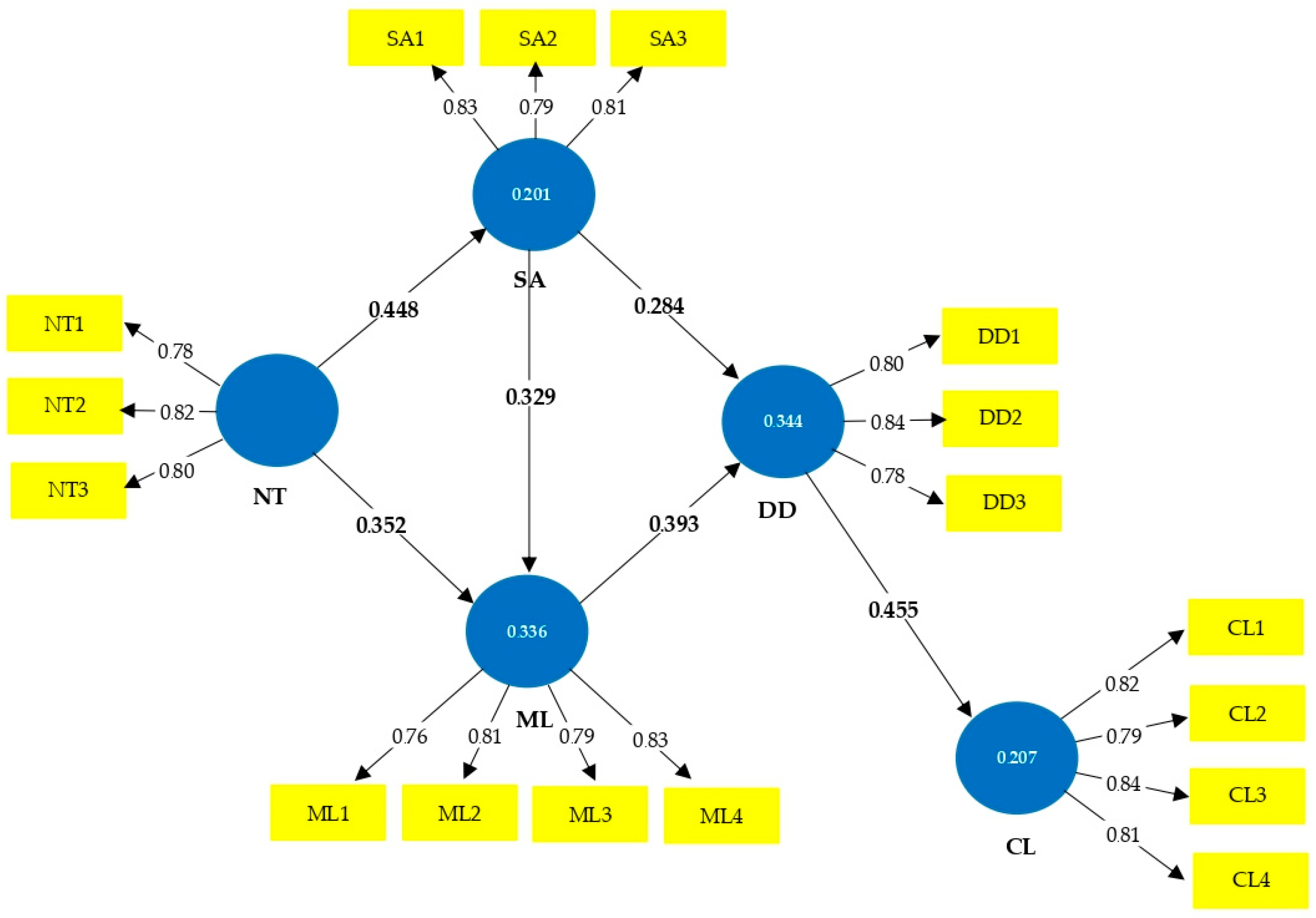

After establishing acceptable measurement quality through confirmatory factor analysis, the structural model was examined to assess the relationships among the five latent constructs: NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL. The structural model demonstrated good explanatory capacity, with the key relationships summarized in

Table 9 and illustrated in

Figure 2.

All six hypothesized direct relationships (H1–H6) were statistically significant at the

p < 0.001 level. NT showed the largest standardized association with SA (β = 0.448), while DD showed the strongest association with CL (β = 0.455). Additional significant associations were observed between NT and ML (β = 0.352), SA and ML (β = 0.329), and ML and DD (β = 0.393). All standardized path coefficients exceeded β = 0.20, indicating moderate to substantial associations within the specified structural model [

43].

Mediation analysis indicated that H7 and H8 were supported by the data. The indirect effects (β = 0.058 and β = 0.061) had 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals that did not include zero, indicating statistically reliable but small mediation effects [

52].

To contextualize the practical contribution of these indirect effects, the total effect of NT on CL within the specified structural model (i.e., the sum of indirect effects) was β = 0.119. The pathway NT → SA → DD → CL accounted for 48.7% of this total effect (0.058/0.119), whereas NT → ML → DD → CL accounted for 51.3% (0.061/0.119). Because the model does not specify a direct NT → CL path, the association between NT and CL is fully mediated by these two pathways. This means that NT influences CL only through its impact on the mediating variables in the specified paths. Importantly, although these mediation effects are statistically reliable, they are small in magnitude. Thus, the practical implication is that NT’s effect on CL operates entirely through modest, indirect mediation.

The model explained substantial variance in the key constructs, as indicated by the coefficients of determination (R2): 0.201 for SA, 0.336 for ML, 0.344 for DD, and 0.207 for CL. Each R2 met or exceeded the 0.20 benchmark considered acceptable for educational and behavioral research [

43], indicating moderate explanatory power of the proposed model.

The model fit the data well, as indicated by the following indices: χ

2/df = 1.61, CFI = 0.957, GFI = 0.917, AGFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.042, and SRMR = 0.041. These values satisfy the recommended model fit criteria by Hu and Bentler [

47], confirming the model’s appropriateness for the data.

Collectively, these results strongly support the structural model, demonstrating robust relationships that explain substantial variation in engagement with smart agriculture, mathematical literacy, data-driven decision-making, and community learning outcomes.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that in drought-sensitive agricultural contexts, NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL are intricately interconnected. These elements do not function independently; instead, they are linked through complex cognitive, technological, and social processes that collectively shape how communities acquire knowledge and make effective, impactful decisions. The interdependence of these competencies points out the value of integrated approaches for fostering holistic learning and adaptive decision-making in challenging agricultural environments.

4.1. NT Provides Support for Both ML and SA

NT requires farmers to regularly engage with numerical information in their daily routines, as they manage land, budget water, and handle risks. These proportion-based principles strengthen farmers’ ability to interpret quantities, evaluate trade-offs, and reason under uncertainty through repeated practice. These characteristics help explain the observed links between NT, SA, and ML. The embedding of quantitative reasoning into daily farming allows NT to establish a cognitively supportive environment, making it easier for farmers to interpret sensor outputs, dashboards, and digital reports generated by SA technologies. In this sense, NT links to more purposeful tech engagement, rather than symbolic or trend-based adoption.

This interpretation aligns with earlier research suggesting that NT encourages logical, evidence-based thinking in water management and climate-sensitive farming systems [

20,

21]. The present findings extend this literature by suggesting that NT is linked to learning-related processes. In particular, NT supports mathematical reasoning in everyday agricultural decisions. Furthermore, the observed relationship between NT and ML fits the principles of RME. RME emphasizes that mathematical understanding develops best through work with meaningful, real-world situations rather than abstract procedures [

4,

5]. The NT farming environment offers such a context. It integrates mathematical problem-solving into daily work and supports the idea that non-formal learning environments play a key role in developing quantitative skills.

4.2. SA Serves as a Vital System Which Enables People to Connect Their Reading Abilities to Making Informed Choices

SA emerges as an important mechanism connecting foundational competencies with decision-related practices. By generating continuous streams of information through sensors, dashboards, and digital monitoring tools, SA requires farmers to engage in cognitively demanding activities such as reading graphs, interpreting numerical indicators, and identifying temporal patterns in environmental data. These requirements help explain the close associations observed among SA, ML, and DD.

This perspective is consistent with prior agricultural research, which emphasizes that the adoption and effective use of smart farming technologies involve both cognitive and technical dimensions. Previous studies have shown that farmers may underutilize smart agriculture systems when numerical reasoning and data interpretation skills are limited [

14,

15,

17,

18]. The present findings add to this literature by suggesting that engagement with SA is not only associated with existing mathematical competencies but may also facilitate their further development through repeated interaction with data-rich farming tools.

In addition, SA appears to be closely associated with DD practices, which in turn are linked to community-level learning processes. Digital engagement facilitated by SA enables farmers to share observations, compare interpretations, and collaboratively make sense of farm-related information. These practices resemble established models of community-based learning and agricultural extension, in which collective reflection and shared problem-solving are central. Rather than replacing social learning processes, SA technologies appear to complement and modernize them, supporting coordinated learning and action in drought-prone agricultural communities.

4.3. Organizations Need ML as Their Fundamental Decision-Making Tool, Which Enables Them to Analyze Data for Making Choices

ML and DD are closely linked, emphasizing the need to distinguish cognitive skills from decision-making behaviors. Mathematical literacy means interpreting, reasoning with, and applying quantitative information in real-life situations [

3]. ML helps farmers work with complex agricultural data and use quantitative reasoning, not just intuition, to evaluate evidence, compare options, and justify actions. Building on this association, it is important to note that information alone does not ensure sound decisions in data-intensive work. Research shows that good data-driven practice depends not only on having data but also on processing, interpreting, and using quantitative information to act [

29,

35]. Our findings support this; mathematical literacy is strongly related to data-driven decisions in agriculture and is a key skill.

Nevertheless, even with this strong relationship, it is crucial to recognize that mathematical literacy and data-driven decision-making do not conceptually overlap, nor do they dominate one another. ML provides the cognitive foundation for interpreting and reasoning with data, while DD puts these skills into action. Thus, their relationship demonstrates how cognitive skills enable effective decision-making in practice, rather than indicating that the two concepts are the same or ranked hierarchically. ML, DD, and CL benefit groups, not just individuals. Data-informed choices help communities solve problems, assess shared conditions, reflect on evidence, and adapt to climate uncertainty. This aligns with prior research on community learning and climate adaptation, which emphasizes sharing information, evidence-based dialogue, and collective action to build community resilience [

24,

31].

4.4. Mediating Pathways and Theoretical Contribution

The mediation results for H7 and H8 show that NT is indirectly associated with CL. This occurs through two specific relational pathways. First, NT leads to SA, which then leads to DD, and finally to CL. Second, NT leads to Mathematical Literacy (ML), which then leads to DD and CL. These findings suggest that using smart technologies and developing quantitative skills are key mechanisms linking NT farming practices to community learning processes.

The indirect effects in these pathways are statistically reliable but modest in size. This means mediation explains only a small part of the NT–CL association in the model. NT should not be seen as directly shaping community learning outcomes. Instead, NT is associated with conditions that help people use smart agricultural technologies and develop mathematical literacy. These, in turn, are linked to data-driven collective decision-making practices.

SA mainly provides continuous data access, monitoring, and shared interpretation [

53,

54]. ML supports the ability to interpret quantitative information and assess alternatives. Together, these processes are linked to collaborative learning and community-level adaptation. The findings suggest a layered, indirect connection rather than a strong direct pathway between NT and CL.

These results add to previous research in STEM education and agricultural learning. Earlier studies showed that practice-based and context-embedded tasks can improve reasoning and problem-solving skills [

10,

11,

13]. Most existing research has focused on individual or classroom-level learning. This study shows that technology-supported agricultural practices are linked to learning processes at the community level, especially in non-formal, work-based settings.

Overall, the mediation results suggest that structured farming systems, such as NT, when used with smart technologies, are associated with supportive learning environments. These environments support both individual skill development and collective adaptation. In drought-affected communities, they seem to help turn individual skills and technology use into shared learning practices. Still, the indirect effects are small, and the study is cross-sectional, so the findings should be seen as associational, not causal. Future research using longitudinal or experimental methods is needed to better examine these links over time.

The findings indicate that, in drought-prone rural communities, engagement with structured farming practices and smart agricultural technologies is associated with higher reported levels of mathematical literacy. These results suggest that everyday farm work may provide contexts in which mathematical reasoning is regularly applied, rather than demonstrating developmental change over time.

5. Limitations

Several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. First, participants were selected based on their prior exposure to self-agency (SA) technologies, which was appropriate for investigating learning and decision-making within technology-rich farming environments. However, this sampling approach may introduce selection bias and restrict the generalizability of findings to farmers who lack experience with smart farming technologies. Consequently, the relationships observed in this study reflect associative patterns among technologically engaged farmers, rather than providing evidence of technology adoption effects more broadly. Moreover, although a high response rate was achieved, 320 usable questionnaires out of 350 distributed, or 91.4%, potential non-response effects cannot be fully ruled out. Systematic differences may still exist between respondents and non-respondents, such as variations in time availability, research interest, or engagement with innovation. Combined with the eligibility criteria, these factors suggest that the sample primarily represents more active and technology-supported farmers and learners, potentially limiting the broader applicability of the study’s conclusions.

Second, the cross-sectional design only shows associations. It does not allow causal inference or reveal changes in ML, DD, or CL over time. Longitudinal and experimental designs are needed to track development and identify causes across farming cycles and climates. Third, the study used self-reported questionnaire data, which may be subject to response biases. While procedural safeguards and statistical assessments were used to reduce these risks, some bias may remain. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings and point to future research directions.

7. Conclusions

This study shows that agricultural practices grounded in NT develop ML. NT integrates proportional reasoning, land-use planning, water budgeting, and stepwise risk management. SA technologies support these processes. NT creates a cognitive framework that encourages quantitative thinking in daily farming. SA enhances this process by providing steady streams of sensor and environmental data through dashboards and monitoring tools. Farmers using these data systems must interpret numbers, spot patterns, and use mathematical reasoning. As a result, ML becomes a key competence. ML predicts DD. Decision-making then shapes CL.

The mediation results show that SA and ML together amplify NT’s influence on CL. These pathways show that structured farming principles, technological engagement, and quantitative skills interact. They transform individual learning into collective knowledge sharing, coordinated decision-making, and adaptive capacity in drought-prone communities. These findings indicate that agricultural settings can serve as authentic learning environments for ML beyond formal education. By empirically linking NT, SA, ML, DD, and CL, this study gives a more integrated understanding of how cognitive skills and technology-supported practices foster community learning and resilience in climate-sensitive agricultural systems.

Future research can extend these findings in several important directions. First, longitudinal studies could track changes in ML across multiple farming cycles to capture patterns of development and sustain impact over time. Second, researchers could evaluate the effectiveness of targeted ML interventions within rural communities, assessing how specific educational strategies or training programs influence farmers’ quantitative reasoning and decision-making skills. Third, further investigation is needed into how different technological environments, such as varying access to digital tools, sensor networks, and data platforms, influence the nature and outcomes of data-driven learning in agriculture. In combination, these research avenues would deepen understanding of how to best support the development of ML and data-driven decision-making in diverse agricultural contexts.