1. Introduction

The nematocidal properties of

Pleurotus ostreatus against phytopathogenic nematodes have been tested in various experiments since its discovery by G. Barron [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Nematodes infect many vegetable crops, as well as major agricultural crops, such as sugar beet. One of the most serious problems in sugar beet cultivation is

Heterodera schachtii, a cyst nematode that significantly reduces root yield and sugar content, and is a globally significant pest of sugar beet [

3,

6]. A broad range of plants contribute to its persistence in the soil. Species from numerous families, including Chenopodiaceae and Brassicaceae, serve as hosts for this pest. Both crop plants, such as beets and spinach, and many weed species can be affected and support its survival [

7]. For this reason, its control is difficult, and chemical treatments pose environmental risks; therefore, in many countries, including Poland, no chemical substances are officially registered for nematode control in sugar beet crops. Consequently, non-chemical strategies for managing phytopathogenic nematodes are highly desirable [

6]. Currently, biological methods such as crop rotation and the use of tolerant cultivars are the most common approaches to

H. schachtii control. Another possibility is the use of nematocidal plants, which prevent the pest from completing its life cycle [

6]. Among these are oilseed radish (

Raphanus sativus var.

oleiformis) and white mustard (

Sinapis alba), although not all varieties exhibit nematocidal properties [

6]. Such trapping crops should be used as part of integrated plant protection strategies, together with crop rotation and tolerant sugar beet varieties. Currently, growing of nematode-resistant trap crops such as oil or mustard together with tolerant sugar beet varieties are a possible management strategy to combat

H. schachtii in European agriculture [

6]. The activity of trap crops against

H. schachtii is mainly related to chemical signals released into the soil through roots’ exudates, although their effects depend on the nematode density and environmental conditions. The impact on cyst nematode population density is primarily due to on the stimulation of hatching by root exudates and the penetration of plant roots by the nematodes, which ultimately prevents them from completing their life cycle [

8,

9]. The efficacy of resistant trap crops in controlling nematodes depends on the establishment of a crop stand capable of producing sufficiently high biomass and root density. A key prerequisite for achieving this is early sowing, carried out immediately after the harvest of the preceding crop. However, substantial variation may occur depending on the trap crop cultivar and prevailing environmental conditions. Moreover, unfavorable autumn weather, such as prolonged drought or low temperatures, can negatively influence trap crop growth and, consequently, reduce their effectiveness in lowering nematode populations. The cultivation of trap crop mixtures composed of different plant species is increasingly promoted and adopted within the framework of European agricultural policies, however, their real nematocidal activity remains unclear [

6].

The reduction in nematode populations in soil can also be achieved by incorporating various dried and powdered plant leaves or mushroom stems. For example, rubber plant leaves, orange peels, and oyster mushroom stems have been shown to reduce

H. goldeni populations by at least 80% [

10].

However, the effectiveness of trap crops, such as radish varieties, may be lower than other biological or chemical control methods, they offer notable environmental and economic benefits, such as serving as green manure, being harmless to agricultural soil, mitigating soil erosion, and lowering nematode management costs [

8,

9].

The mycelia of

P. ostreatus may differ in their nematocidal activity [

11,

12]. Previous studies have shown that mycelia differ in their growth rate, optimal temperatures for vegetative growth and activity against nematodes [

11,

12]. When introduced into the field,

P. ostreatus mycelia are influenced by multiple environmental factors, including the presence of other plants such as oilseed radish, white mustard and sugar beet. This mutual influence has not been previously studied, and the interactions between oyster mushroom mycelium and nematocidal plants remain unclear. Fulfilling this gap in knowledge may have a great importance in practical field applications.

This study aimed to examine whether the combined application of P. ostreatus mycelium with plant root exudates or seeds’ secretions, influence on nematode suppression. The research provides the first insight into whether trap plants may modify the effectiveness of P. ostreatus mycelium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organisms

The plant materials used in the experiment included the seeds and seedlings of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris), variety Janetka, kindly provided by Kutnowska Hodowla Buraka Cukrowego (Kutnowska Sugar Beet Breeding Company, Kutno, Poland); oilseed radish (Raphanus sativus L. subsp. oleiformis Pers.) cv. Romesa; and white mustard (Sinapis alba L.) cv. Bardena, both purchased locally. All seeds were surface-sterilized prior to use, either directly in the experiments or before seedling production. Root exudates were obtained by immersing the roots of well-developed seedlings (10 plants per sample) in sterile deionized water (5 mL) for 24 h.

The

Pleurotus ostreatus mycelial strains used in the experiments included the following: Po1-5dix27, Po2-15dix17, Po4-2dix1, Po4-14x17, Po4-3dix17, Po2-20dix23, Po4-8, Po4-30, R01, and R08. These strains represented laboratory-generated crossed strains (heterokaryons) (e.g., Po4-14x17), monokaryons (homokaryons) derived from basidiospores (Po4-8, Po4-30), and heterokaryons produced according to Buller’s rules (Po1-5dix27, Po2-15dix17, Po4-2dix1, Po4-3dix17, Po2-20dix23). Strains R01 and R08, commonly used in commercial oyster mushroom cultivation, served as reference controls. All strains were selected based on previous assessments of their direct nematocidal activity [

9,

10] and partially unpublished data. Prior to use in the laboratory pot experiment, the mycelia were pre-cultured on a PDA medium.

The cysts of

Heterodera schachtii were isolated from naturally infested soil following the methodology described by Kaczorowski [

13]. Prior to the main procedure, soil samples (100 ± 0.1 g) were air-dried at room temperature and sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove straw residues. Cysts were then extracted using a Seinhorst apparatus, which employs a water–soil suspension and separates organic and inorganic fractions based on their density and flotation properties. Extraction was carried out at an ambient temperature of 20 °C for 8 min, with a flow rate of 1.6 dm

3/min.

Cysts recovered from this process were further separated from smaller organic particles using a dissecting needle under a stereomicroscope (ProLab Scientific Motic SMZ160, Laval, QC, Canada). The isolated cysts were collected and stored in Petri dishes under refrigeration until use in the experiments.

Nematodes

Caenorhabditis elegans N2 were used as a model culture and it was obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) (University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN, USA) and propagated according to the methodology provided by Stiernagle [

14].

2.2. Experiment Methodology

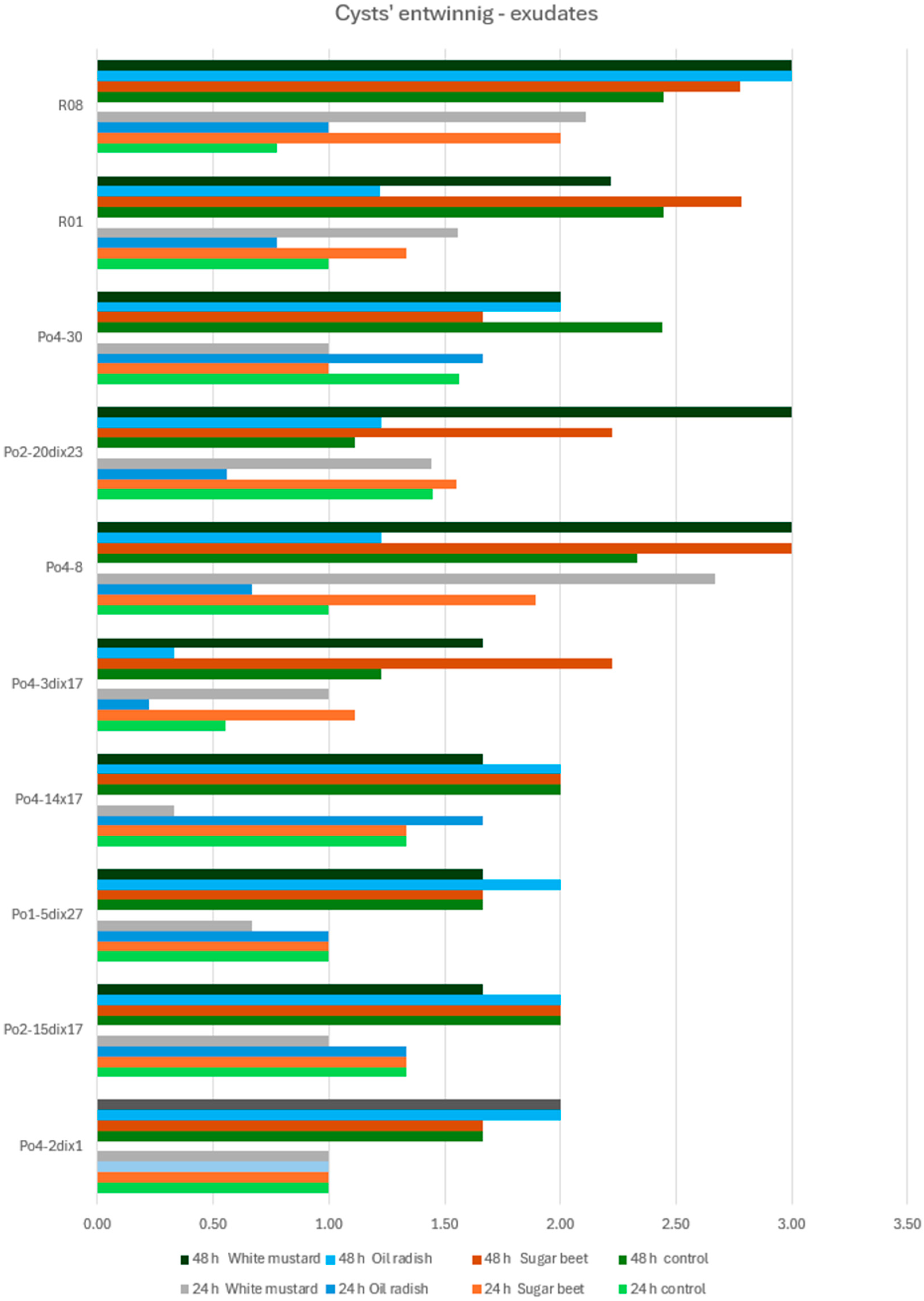

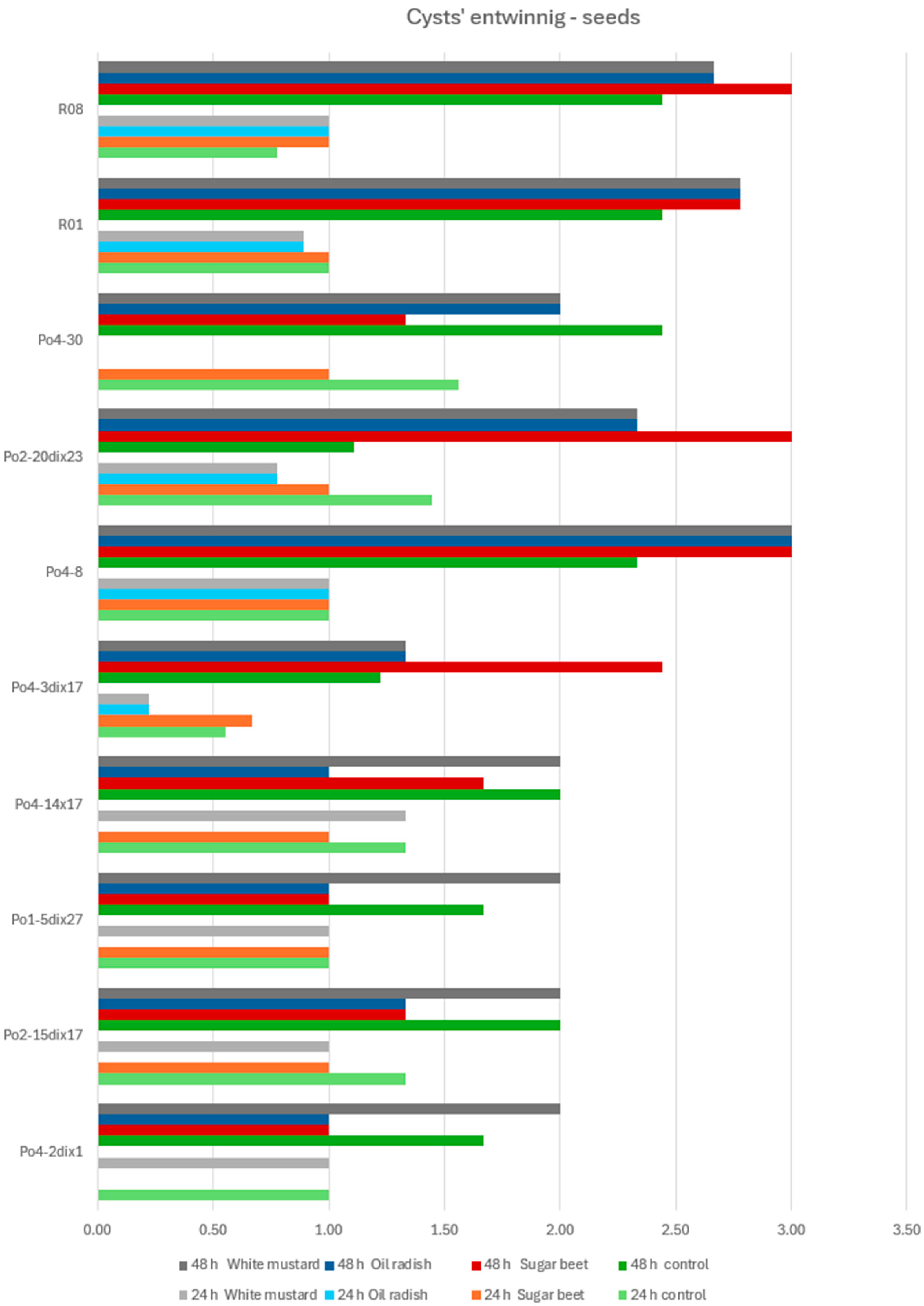

The experiments were conducted on an agar medium (water agar, WA) in Petri dishes previously inoculated with P. ostreatus mycelium. The mycelium was incubated for two weeks until it fully colonized the WA surface. Subsequently, either (1) seeds of white mustard, oilseed radish, or sugar beet were placed on the medium, or (2) root exudates obtained from seedlings of the same plant species were applied. In each experimental treatment, C. elegans nematodes or H. schachtii cysts (3 per point) were introduced at the point of seed placement or exudate application. Control dishes contained no seeds or exudates.

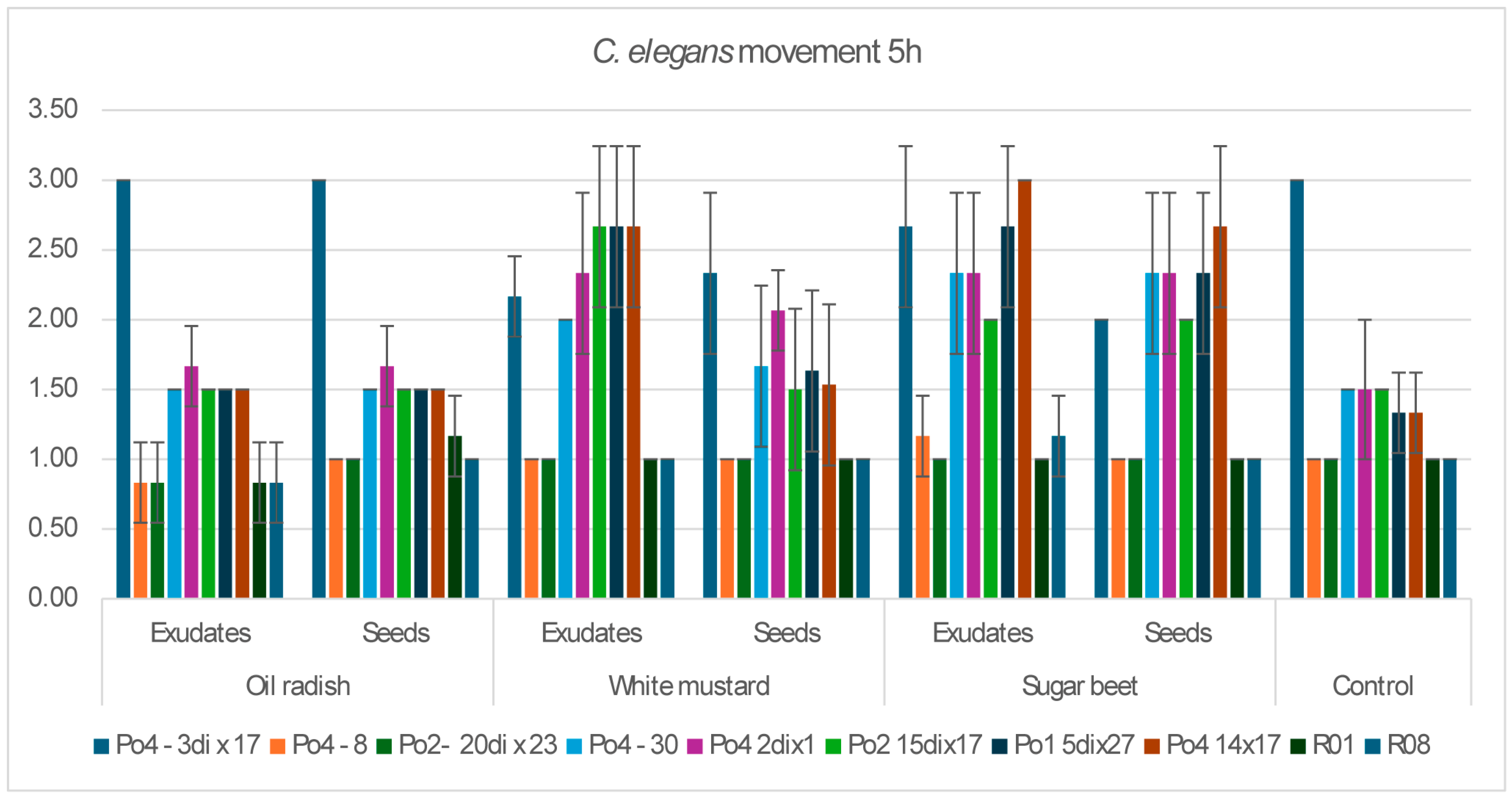

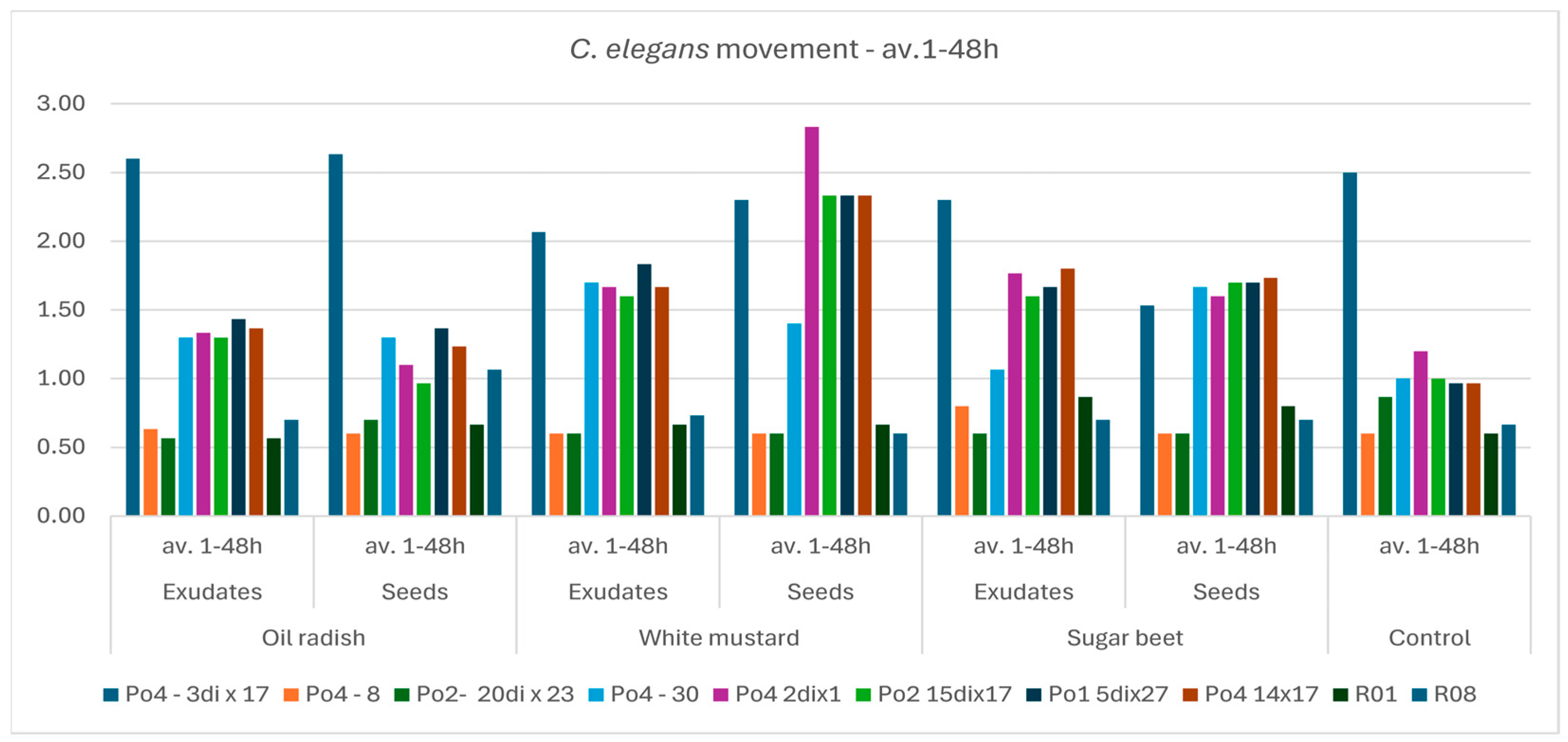

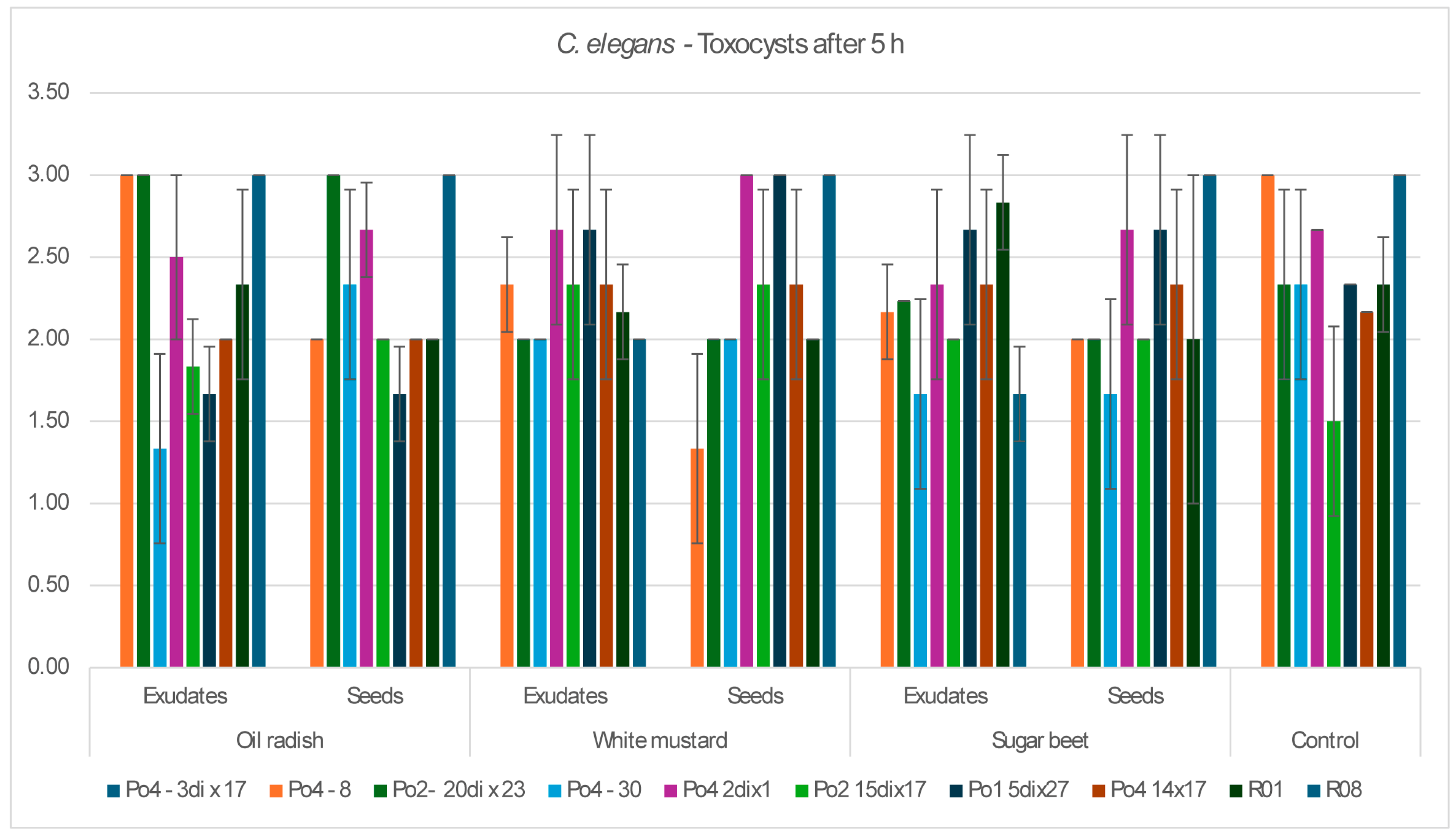

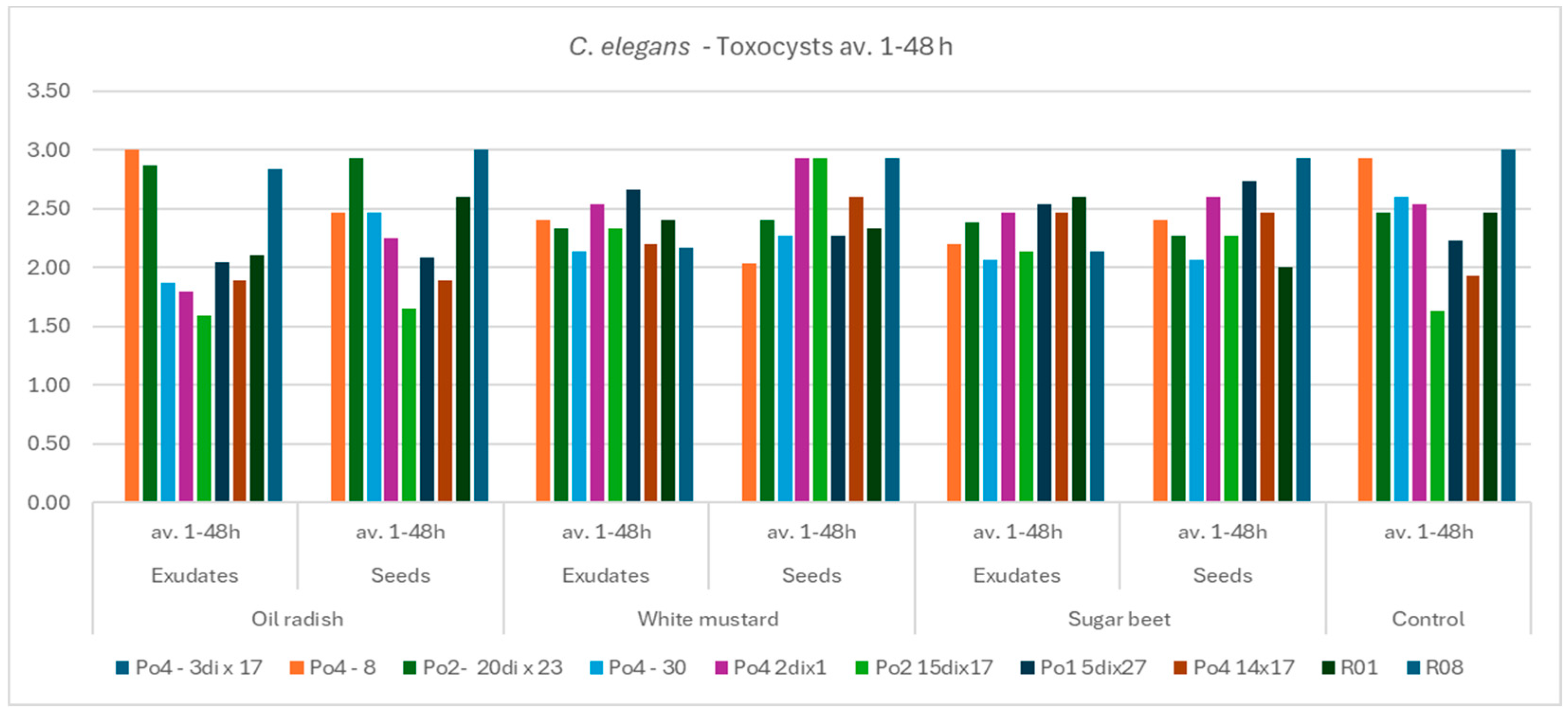

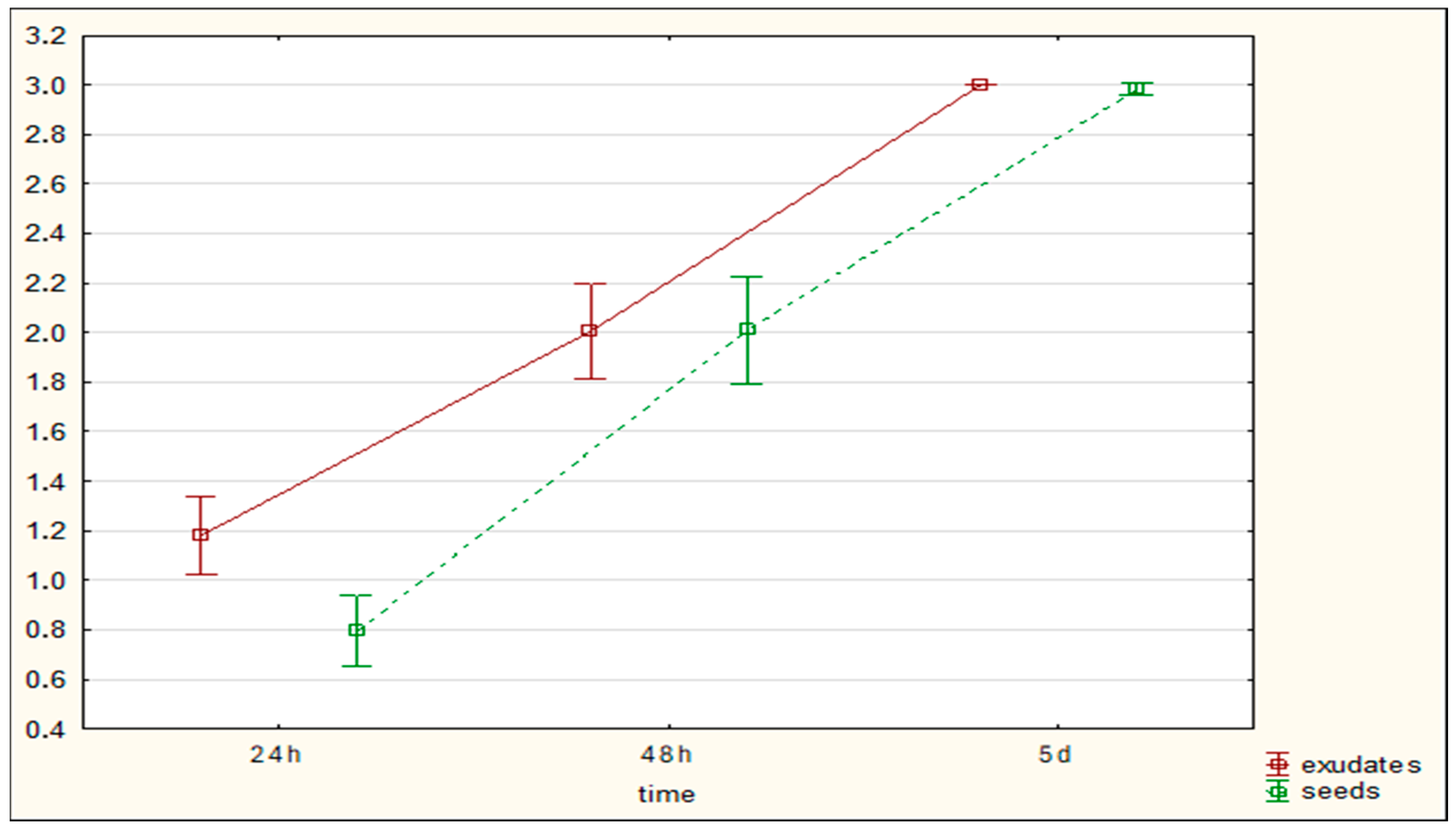

The aim of the study was to determine whether plant-derived materials (seed secretions or root exudates) influence potential changes in the activity of the mycelium against the tested nematodes. Parameters assessed included the degree of

C. elegans immobilization, the extent of

H. schachtii cyst overgrowth, and the ability of the mycelium to produce toxin-forming structures (toxocysts). Evaluations were performed according to previously established rating scales [

11,

12] ranging from 0 to 3, where a score of 3 indicated the highest level of nematode movement. The desired outcome—complete inhibition of movement, nematode death, and overgrowth of nematode bodies by mycelium—corresponded to a score of 0. For toxocyst formation, the highest score was 3.

Observations were conducted at 1, 3, 5, 24, and 48 h after inoculation, and additionally after 5 days in the H. schachtii treatments. The results are presented only for the most informative observation points. Each experimental variant was performed three times on separate plates, using the following scales for H. schachtii assessments:

Cysts of Heterodera schachtii overgrowing:

0—no hyphal reaction to the presence of the cyst;

1—mycelial hyphae directed towards the cyst;

2—fine hyphae entwining the cyst;

Toxocysts production:

0—no toxocysts developed;

1—few toxocysts;

2—average number of toxocysts;

The result are presented in graphs as averages for all assessments. Data were collected in 2023–2024.

2.3. Calculations and Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica v. 13.3. The data were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Kruskal–Wallis test, and the significance of differences (p = 0.05) was determined based on multiple comparison tests.

Correlation coefficients were calculated, using Microsoft Excel, between toxocysts formation and movement of C. elegans.

4. Discussion

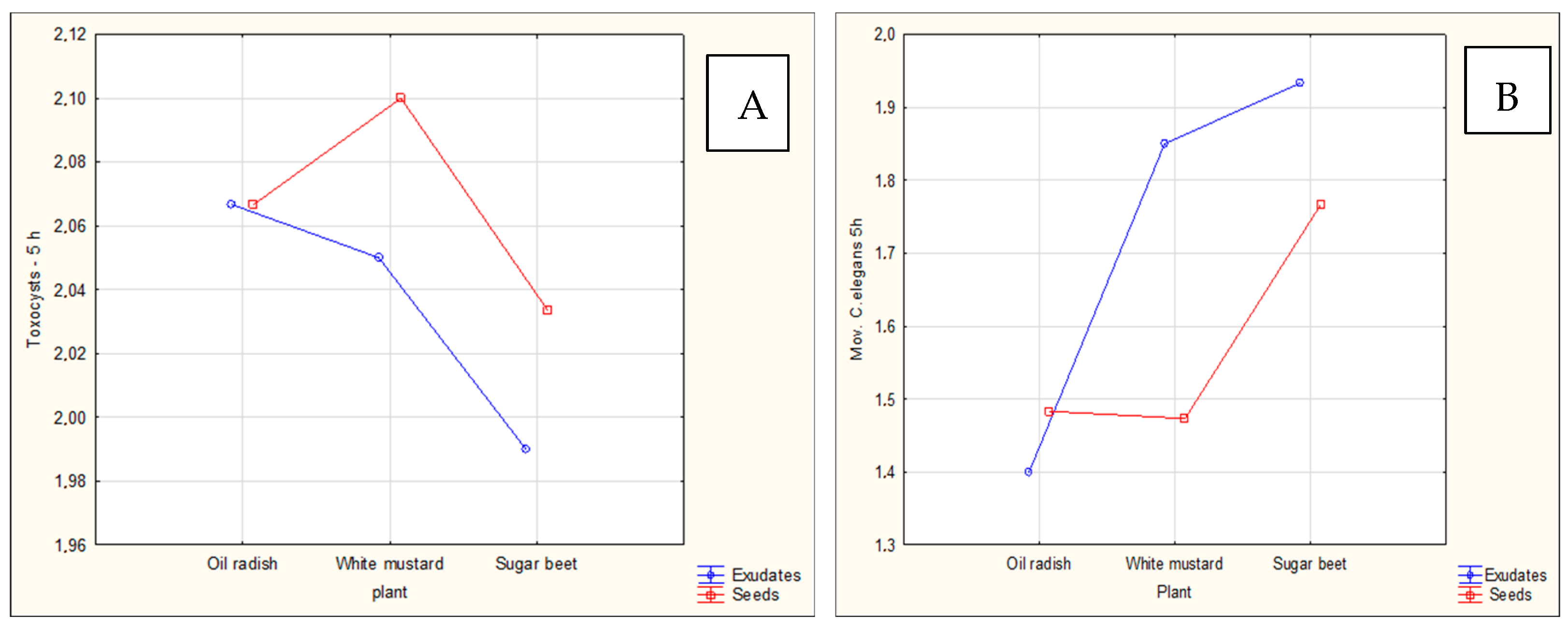

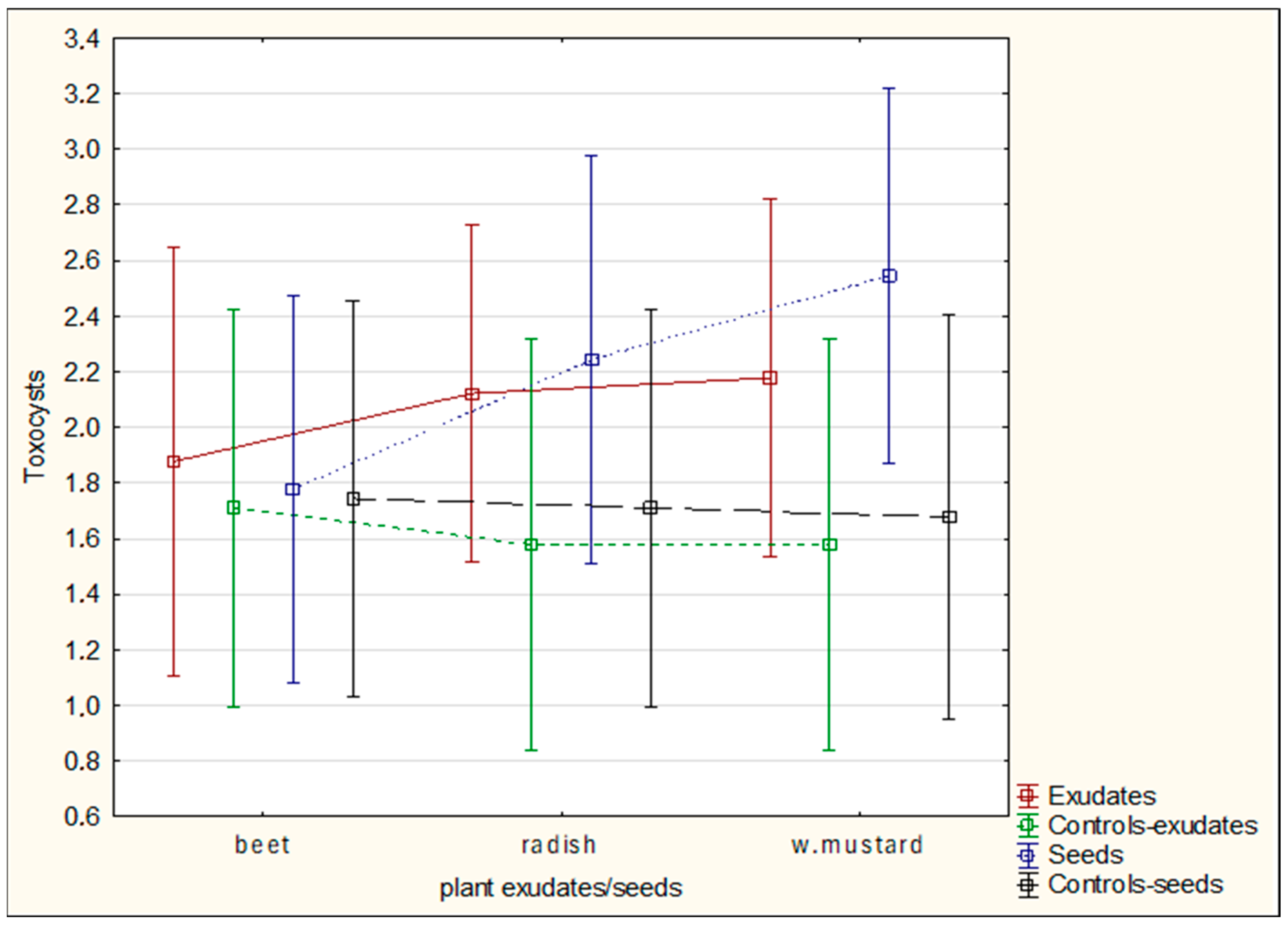

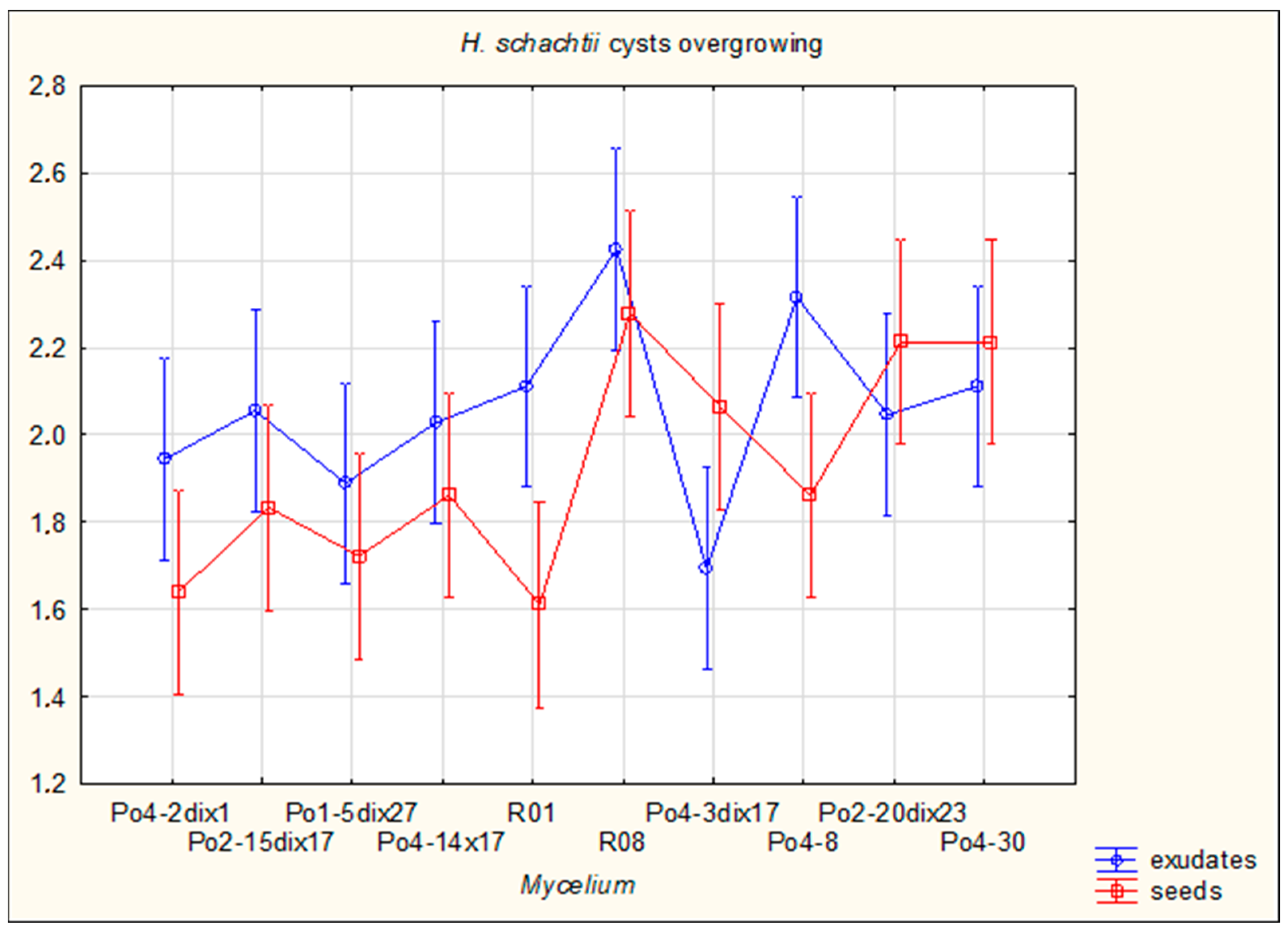

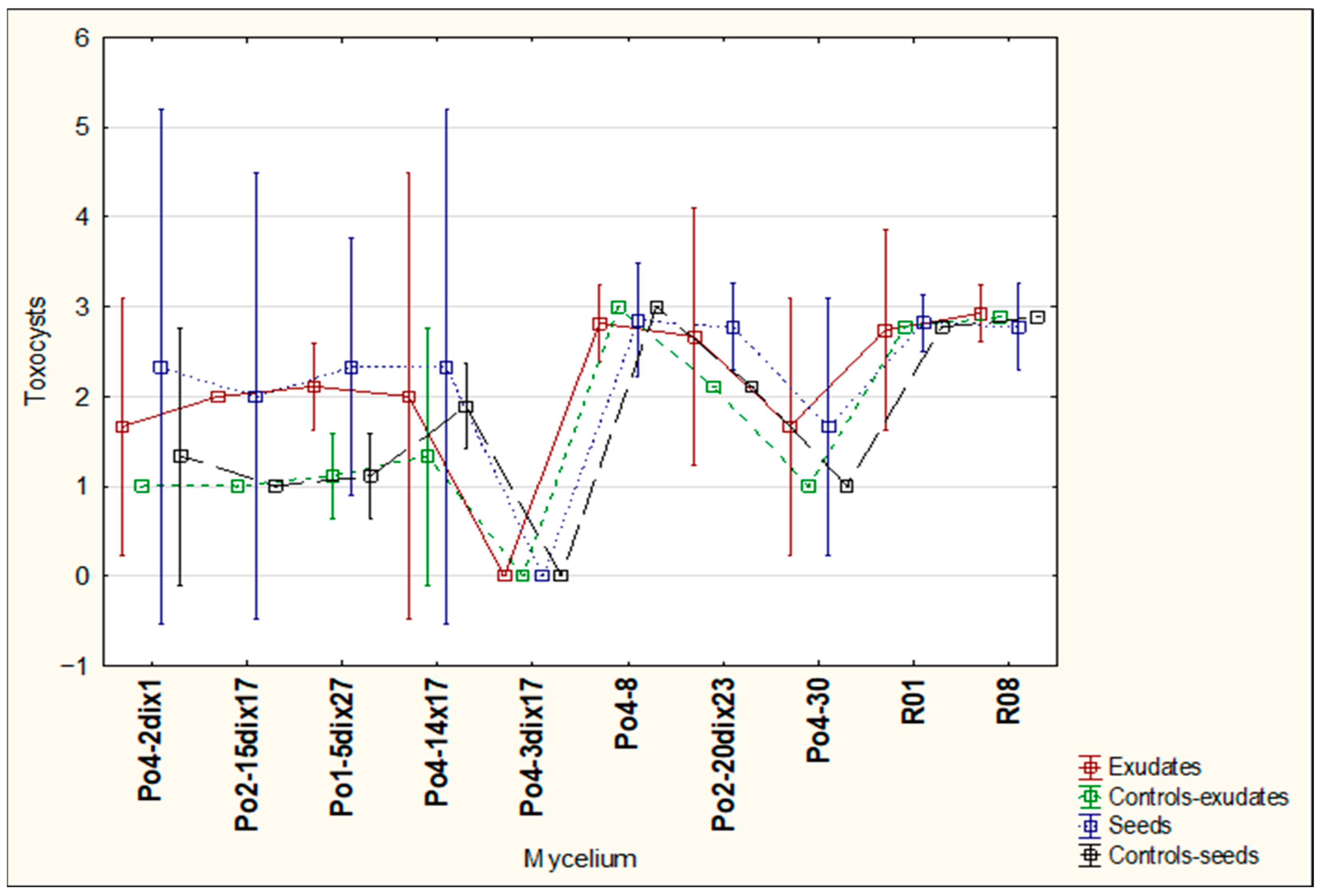

Mycelia of Pleurotus ostreatus demonstrated the ability to kill the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and to entwine and overgrow the cysts of the sugar beet cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii. However, when the mycelia activity was tested in the presence of seed secretions and root exudates, their efficacy did not change significantly. These findings suggest that root exudates of potential trap plants do not negatively affect P. ostreatus mycelium activity. These observations were consistent across all tests, indicating the potential of this approach as a tool for controlling H. schachtii populations and improving soil organic matter.Nevertheless, the present experiments do not isolate or clarify the direct influence of the plants themselves and mycelia on the hatching of H. schachtii eggs, and to our knowledge, such studies have not yet been performed. Therefore, further field experiments are needed that involve the simultaneous introduction of effective mycelium and trap plants into the soil. Additional trap plant species and varieties should also be tested.

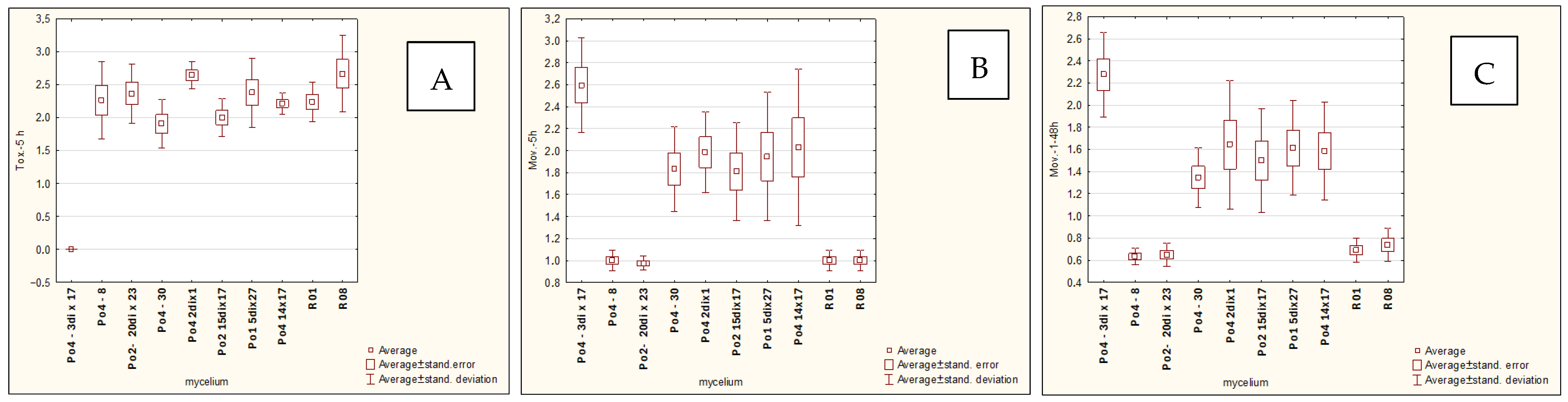

A tendency toward reduced mycelial activity was observed in the presence of oilseed radish, however not proved by ststistical analyses. The research showed that toxicocyst production is not strongly correlated with the ability of the mycelia to inhibit the movement of

C. elegans. Although these correlations (

Table 1) are weak, they nevertheless reflect general trends in the activity of

P. ostreatus mycelia against nematodes. This observation confirms the established mode of toxic action of vegetative mycelium on nematodes, while at the same time suggesting that additional mechanisms contribute to the nematocidal activity of this mushroom [

15,

16]. The results clearly indicate that the mycelium’s nematocidal activity does not rely solely on toxicocyst production. For example, the mycelial line incapable of producing toxicocysts, Po4-3dix17, still demonstrated the ability to entwine

H. schachtii cysts. The most active strains, Po4-8 and R08, reached maximum toxicocyst production and inhibition of

C. elegans within only 5 h, which may indicate their overall effectiveness against

C. elegans. For these strains, activity was not influenced by the plant species used, whereas slight plant-dependent effects could be observed in other mycelia.

Among the tested plants, oilseed radish most strongly promoted nematocidal activity against

C. elegans, suggesting that its use as a forecrop or catch crop may be particularly effective in crop rotations aimed at reducing

H. schachtii populations. This finding further indicates that trap plants are unlikely to interfere with mycelial activity in soil environments when both would be applied simultaneously to control the sugar beet cyst nematode. Oilseed radish and leaf radish belong to a group of trap plants known to exhibit strong activity against

H. schachtii, although the final level of cyst depletion depends heavily on cultivar-specific traits. Varieties of white mustard exhibit similar properties in field [

6,

8,

17].

Hauer et al. [

6] recommend cultivating nematode-resistant trap crops such as oil radish or mustard together with tolerant or resistant sugar beet varieties as part of integrated management strategies targeting

H. schachtii in infested fields. However, as demonstrated by Reuther et al. [

18], tolerant sugar beet varieties do not reduce nematode populations; instead, population levels may even increase during cultivation, reaching 147% of the initial level in the case of the variety ‘Kleist’. Consequently, the identification of complementary methods that reinforce current integrated strategies is essential for more effective management of

H. schachtii. This possibilty may be achieved by using

P. ostreatus mycelium as a namatocidal agent in the field soil. This conclusion can be supported by our current previous research [

12,

19] and the research of others [

3,

5].

In our experiments, we tested only two species/varieties of

H. schachtii–trapping plants. However, up to twelve species may be classified within this group; among them, varieties of radish, white mustard, and rye appear to be the most effective [

7]. These species differ in their capacity to stimulate

H. schachtii hatching and subsequently inhibit its further development. For some species, the reduction in

H. schachtii populations did not differ significantly from the fallow control. Nevertheless, unlike fallow soil, these plants provide the additional benefit of green manure, making them more advantageous overall [

7]. Our proposal gives the opportunity to control

H. schachtii and enhance soil in green manure.

The mycelium of

P. ostreatus, in addition to entwining

H. schachtii cysts, produces the volatile compound 3-octanone [

20]. This compound may prove useful in nematode management. Since now only one research was developed to test the activity of 3-octanone against

C. elegans, and to our knowledge, it was not tested against other nematode species, including

H. schachtii [

20]. Khoja et al. [

21] tested volatiles secreted by

Metarhizium brunneum against

Meloidogyne hapla. The volatiles were 1-octen-3-ol and 3-octanone. Both when applied at low doses to plants lured nematodes, and repelled them at high doses. When soil was treated with these active substance very few live

M. hapla were recovered, but the effect was possible only when high doses were applied [

21]. Both substances as volatiles show the potential of to be used as biofumigants.And

P. ostreatus may serve as a source of 3-octanone. On the other hand, Quintanilla et al. [

7], for example, highlight the biofumigation potential of non-host oilseed radish, which could contribute to integrated pest management strategies targeting

H. schachtii.

Resistant varieties of oilseed radish and white mustard are recommended in Central Europe as standard components of

H. schachtii management strategies. These crops should be sown as catch crops before sugar beet cultivation [

22,

23,

24]. A similar strategy has been implemented in Japan, where

H. schachtii was first detected in Hara Village, Nagano Prefecture, in 2017 [

8,

9]. Sakai et al. [

9] reported effective suppression of nematode populations using two leaf-radish varieties that did not support cyst reproduction, in contrast to the control variety. However, they did not quantify the remaining nematode population.

In Europe, breeding catch crops for resistance to

H. schachtii began more than 30 years ago. Field trials have shown that such crops can reduce

H. schachtii population densities by 20–60%, depending on sowing date, plant density, and crop rotation practices [

22,

24]. As forecrops, oilseed radish and white mustard primarily function as green manure species; however, with careful selection of resistant varieties, they can also contribute to reducing

H. schachtii populations [

22,

23]. Enhancing these catch crops with

P. ostreatus mycelium may further strengthen integrated plant protection strategies. Particularly, no negative effects were observed in the case of mycelium nematocidal activity, both on model organism

C. elegans and the target organism—

H. schachtii. However, mycelia for further use should be carefully chosen with respect to their individual nematocidal activity.