Effect of a Long-Term Integrated Multi-Crop Rotation and Cattle Grazing on No-Till Hard Red Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Production, Soil Health, and Economics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cropping Systems

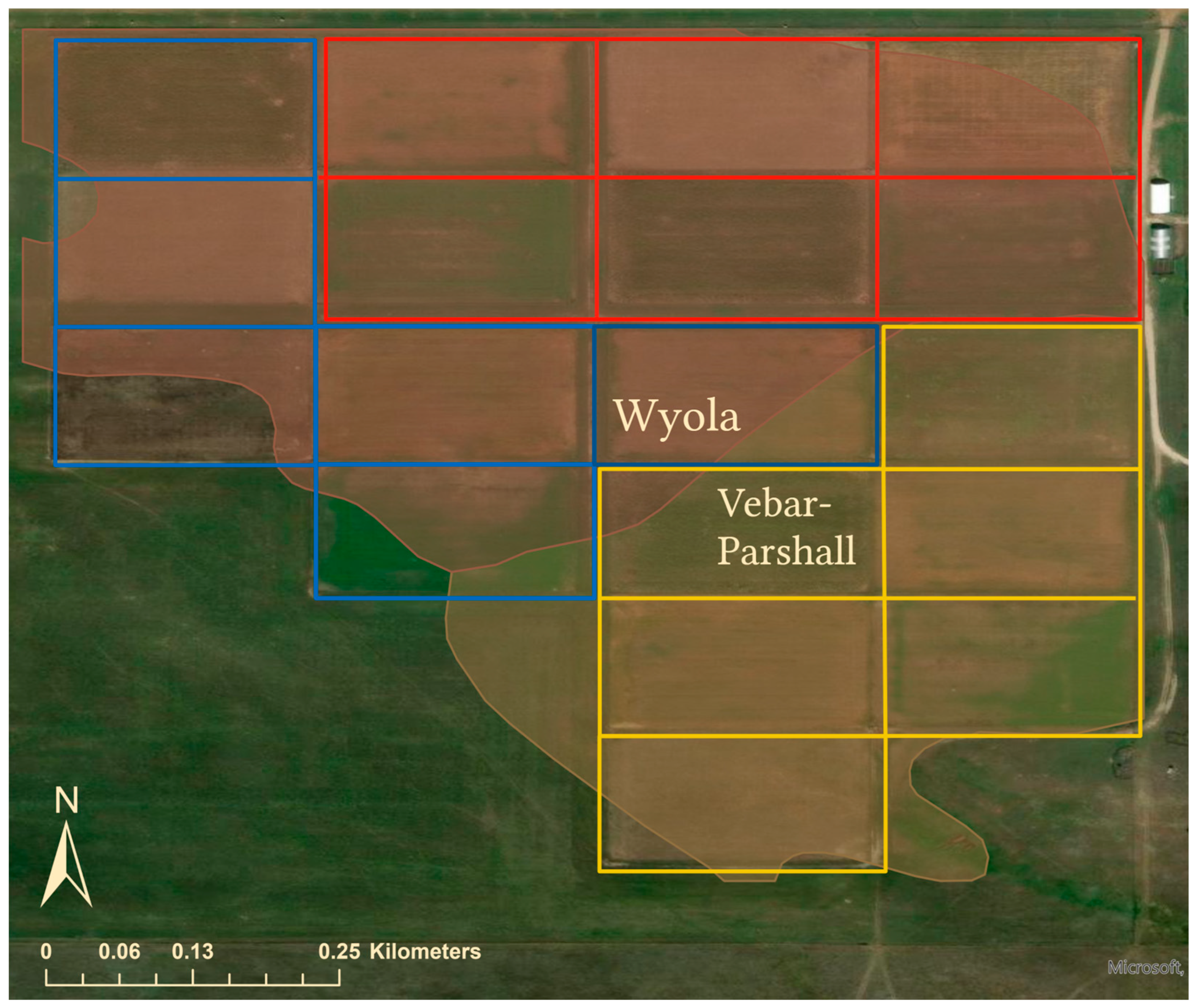

2.1.1. Research Site and Design

2.1.2. Rotation Crop Sequence and Planting Method

2.1.3. Hard Red Spring Wheat Harvest and Forage Sample Collection

2.2. Rotation Crop Beef Cattle Grazing

2.3. Beef Cattle Manure and Urine

2.4. Soil and Climate Data

2.5. Crop Budgets and Economic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hard Red Spring Wheat Grain Yield, Test Weight, and Quality

3.2. Hard Red Spring Wheat Economics

3.3. Soil Fertility

3.4. Beef Cattle Manure and Urine Spreading

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects on Grain Quality

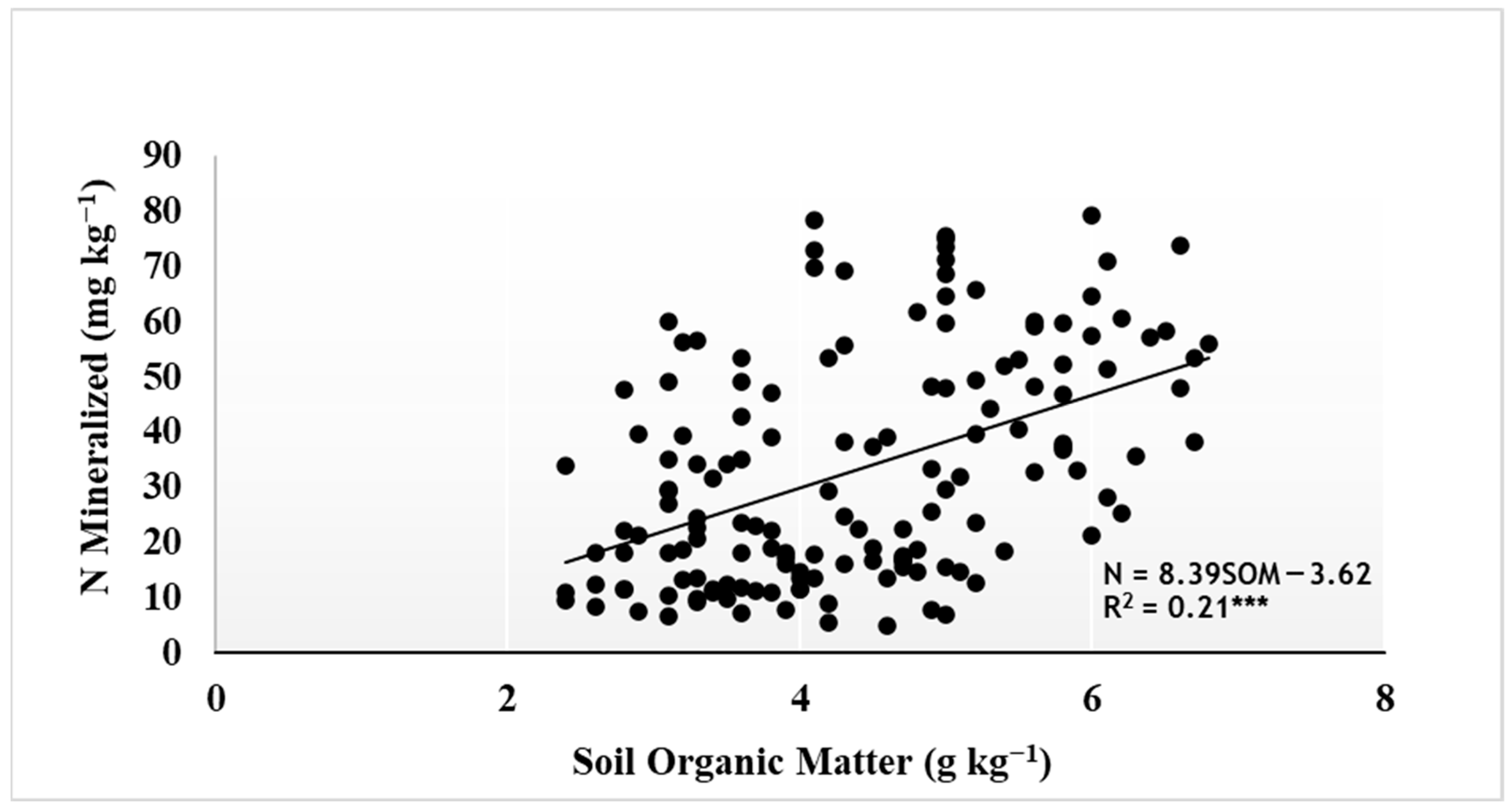

4.2. Soil Fertility and Soil Health

4.3. Weather and Grain Yield

4.4. System Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMF | arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| HRSW-CTRL | hard red spring wheat control |

| HRSW-ROT | hard red spring wheat rotation |

| N | nitrogen |

| P | phosphorus |

| SOM | soil organic matter |

| NDSU-NL | North Dakota State University Nutrition Laboratory |

Appendix A

| Year | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Rain & Temp 1 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| April | Rain (mm) | 42.2 | 60.5 | 26.7 | 27.7 | 15.2 | 87.4 | 33.0 | 12.2 | 34.3 | 15.0 | 6.6 | 105.7 |

| Temp (Max) | 8.5 | 14.7 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 13.6 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 10.6 | 12.0 | 5.9 | |

| Temp (Min) | −1.4 | 0.5 | −4.7 | −9.6 | −1.5 | −2.2 | −1.9 | −6.7 | −0.3 | −4.2 | −3.2 | −3.8 | |

| May | Rain (mm) | 174.5 | 40.1 | 191.8 | 110.7 | 41.9 | 57.4 | 21.3 | 31.0 | 64.0 | 36.8 | 128.8 | 80.5 |

| Temp (Max) | 14.6 | 19.7 | 18.7 | −17.8 | 17.9 | 20.8 | 20.2 | 7.4 | 15.0 | 18.6 | 18.0 | 17.6 | |

| Temp (Min) | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.4 | −17.8 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 4.3 | −17.8 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.9 | |

| June | Rain (mm) | 54.6 | 110 | 56.6 | 128.3 | 118.9 | 49.8 | 32.3 | 107.4 | 66.0 | 27.9 | 27.2 | 51.3 |

| Temp (Max) | 22.7 | 25.6 | 22.6 | −17.8 | 24.5 | 26.4 | 26.0 | 26.9 | 23.5 | 27.2 | 27.7 | 23.7 | |

| Temp (Min) | 10.8 | 11.2 | 10.4 | −17.8 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 11.3 | 10.1 | |

| July | Rain (mm) | 59.2 | 50.3 | 54.1 | 15.0 | 72.9 | 91.7 | 18.3 | 51.1 | 40.9 | 67.8 | 26.2 | 94.2 |

| Temp (Max) | 28.1 | 31.7 | 27.5 | −17.8 | 28.7 | 28.7 | 32.5 | 28.2 | 27.3 | 28.3 | 31.6 | 28.9 | |

| Temp (Min) | 14.2 | 15.3 | 12.1 | −17.8 | 13.5 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 12.5 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 14.3 | 14.1 | |

| Aug. 2 | Rain (mm) | 68.6 | 20.8 | 71.4 | 126.0 | 42.9 | 47.2 | 67.8 | 14.0 | 119.4 | 65.0 | 41.4 | 7.1 |

| Temp (Max) | 27.1 | 27.8 | 27.8 | −17.8 | 28.3 | 28.7 | 25.6 | 29.0 | 26.8 | 29.1 | 28.3 | 29.5 | |

| Temp (Min) | 13.2 | 12.2 | 12.3 | −17.8 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 10.4 | 11.7 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 11.8 | 13.5 | |

| Sep. 3 | Rain (mm) | 44.7 | 5.3 | 62.0 | 50.8 | 34.3 | 67.6 | 57.9 | 46.7 | 231.1 | 21.8 | 3.6 | 23.6 |

| Temp (Max) | 22.1 | 24.4 | 23.9 | −17.8 | 24.3 | 21.1 | 22.0 | 18.0 | 20.4 | 22.0 | 26.3 | 25.6 | |

| Temp (Min) | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8.8 | −17.8 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 5.9 | 8.2 | 9.4 | |

| Oct. 4 | Rain (mm) | 11.2 | 59.7 | 85.1 | 1.8 | 49.8 | 45.7 | 2.0 | 16.8 | 32.0 | 6.6 | 68.6 | 46.7 |

| Temp (Max) | 15.5 | 11.3 | 10.4 | −17.8 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 10.9 | 8.0 | 10.2 | 15.3 | 13.5 | |

| Temp (Min) | 1.7 | −0.6 | −0.5 | −17.8 | 2.1 | 1.1 | −1.0 | −2.1 | −2.8 | −3.3 | 2.7 | 1.3 | |

| Means | Rain (mm) | 65.0 | 49.5 | 78.2 | 65.8 | 53.7 | 63.8 | 33.2 | 39.9 | 84.0 | 34.4 | 43.2 | 58.5 |

| Temp (Max) | 19.8 | 22.2 | 19.6 | −14.9 | 21.8 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 18.3 | 19.0 | 20.9 | 22.8 | 20.7 | |

| Temp (Min) | 8.5 | 8.3 | 7.9 | −17.8 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 8.7 | |

| Treatment | Year | Microbial Biomass | AMF | pH | Soluble Salt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng g−1 soil) | (mg kg−1) | (dS m2) | |||

| HRSW-CTRL | 2017 | 1466 | 45 | 5.9 | 0.22 |

| 2019 | 4485 | 125 | 6.0 | 0.07 | |

| HRSW-ROT | 2017 | 1527 | 51 | 6.4 | 0.25 |

| 2019 | 4462 | 117 | 7.0 | 0.08 |

References

- Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS); United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Leveraging Farm Policy for Conservation: Passage of the 1985 Farm Bill. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/stelprdb1044129-leveraging-farm-policy.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Crop Genetic Improvement. Available online: https://cropsciences.illinois.edu/research-outreach/research-areas/plant-improvement/crop-genetic-improvement (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Sellers, S.; Nunes, V. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer in the U.S. Farmdoc Dly. 2021, 17, 24. Available online: https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2021/02/synthetic-nitrogen-fertilizer-in-the-us.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Edwards, C.A. Crop Rotations in Sustainable Production Systems. In Sustainable Agricultural Systems; Environment & Agriculture, Environment and Sustainability; Edwards, C.A., Rattan, L., Patrick, M., Robert, H.M., Housesitting, G., Soil and Water Conservation Society, Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; Volume 1, 712p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sieverding, H.; Lai, L.; Thandiwe, N.; Wienhold, B.; Redfearn, D.; Archer, D.; Ussiri, D.; Faust, D.; Landblom, D.; et al. Facilitating Crop–Livestock Reintegration in the Northern Great Plains. Agron. J. 2019, 5, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdoff, F.; Harold, V.E. Organic Matter—The Key to Healthy Soils. Organic Matter: What It Is and Why It’s so Important. In Building Soils for Better Crops Sustainable Soil Management, 3rd ed.; Handbook Series Book 10; Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) Program: Athens, GA, USA, 2021; pp. 2–9. Available online: https://www.sare.org/wp-content/uploads/Building-Soils-for-Better-Crops.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Senturklu, S.; Landblom, D.G.; Paisley, S.; Wachenheim, C.; Maddock, R. Frame Score, Grazing and Delayed Feedlot Entry Effect on Performance and Economics of Beef Steers from Small- and Large-Framed Cows in an Integrated Crop-Livestock System. Animals 2021, 11, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, M.D.; Grandy, A.S.; Tiemann, L.K.; Weintraub, M.N. Crop rotation complexity regulates the decomposition of high and low quality residues. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorson, A.D.; Black, A.L.; Krupinsky, J.M.; Merrill, S.D.; Wienhold, B.J.; Tanaka, D.L. Spring wheat response to tillage and N fertilization in rotation with sunflower and winter wheat. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The North Platte Natural Resources District. Agricultural Best Management Practices. Nitrogen Credits for Manure & Legume Crops. Available online: https://www.npnrd.org/programs/best-management-practices/nitrogen-credits-for-manure-and-legume-crops.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Merrill, S.; Tanaka, D.; Hanson, J.D. Soil Water Depletion and Recharge under Ten Crop Species and Applications to the Principles of Dynamic Cropping Systems. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P.R.; Mauchline, T.H. Who’s who in the plant root microbiome? Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schlegel, A.J.; Assefa, Y.; Lucas, A.; Haag, C.; Thompson, R.; Stone, L.R. Soil Water and Water Use in Long-Term Dryland Crop Rotations. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupinsky, J.; Joseph, M.; Karen, L.B.; Marcia, P.; McMullen, B.; Gossen, D.; Kelly, T.; Turkington, T. Managing Plant Disease Risk in Diversified Cropping Systems. Agron. J. 2002, 94, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Official Series Description—Wyola Series. 2022. USAD-NRCS. Available online: https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/W/Wyola.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Soil Survey Staff. Official Series Description—Vebar Series. 2001. USDA NRCS. Available online: https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/V/Vebar.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Soil Survey Staff. Official Series Description—Parshall Series. 1998. USDA-NRCS. Available online: https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/P/Parshall.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Lynch, J.M.; Barbano, D.M. Kjeldahl Nitrogen Analysis as a Reference Method for Protein Determination in Dairy Products. J. Aoac Int. 1999, 82, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senturklu, S.; Landblom, D.G.; Maddock, R.; Petry, T.; Wachenheim, C.; Paisley, S. Effect of yearling steer sequence grazing of perennial and annual forages in an integrated crop and livestock system on grazing performance, delayed feedlot entry, finishing performance, carcass measurements, and systems economics. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 2204–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senturklu, S.; Landblom, D.; Stokka, G.; Cihacek, L. Alternative Intensive Animal Farming Tactics That Minimize Negative Animal Impact and Improve Profitability. In Intensive Animal Farming—A Cost-Effective Tactic; Manzoor, S., Abubakar, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturklu, S.; Landblom, D.G.; Hanna, L.; Parman, B.; Perry, G.A.; Paisley, S. Non-traditional beef heifer management effect on synchronized fixed-time AI and delayed feedlot entry of non-pregnant heifers. In Proceedings of the 2025 ASAS-CSAS Annual Meeting, Hollywood, FL, USA, 6–10 July 2025; Available online: https://2025asasannual.eventscribe.net/searchGlobal.asp (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Midwest Plan Service. Livestock Waste Facilities Handbook; Livestock Wastes Subcommittee of the Midwest Plan Service Facilities Handbook; MWPS: Ames, IA, USA, 1985; Available online: https://archive.org/details/livestockwastefa0000unse (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Miller, R. How Much Manure Will My Animals Produce? Available online: https://extension.usu.edu/smallfarms/files/How_Much_Manure.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Euken, R. Characteristics and value of manure from bedded confinement buildings for beef production. In Proceedings of the Cattle Feeder’s Conference: A New Era of Management, Iowa Beef Center, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 10–11 June 2009; Available online: https://www.iowabeefcenter.org/CattlemenConference/beddedconfinementmanure.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- National Research Council. Soil and Water Quality: An Agenda for Agriculture; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/2132/chapter/10 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Whitehead, D.C. Nutrient Elements in Grasslands: Soil–Plant–Animal Relationships; CABI Pub.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbie, D.R.; Buckthought, L.E.; Shepherd, M.A. The challenge of the urine patch for managing nitrogen in grazed pasture systems. Adv. Agron. 2015, 129, 229–292. [Google Scholar]

- Nanthi, B.; Adriano, D.; Mahimairaja, S. Distribution and bioavailability of trace elements in livestock and poultry manure by-products. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Adams, W. Gaseous N emission during simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in grassland soil associated with mineral N fertilization to a grassland soil under field Conditions. Soils Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, M.; Gelderman, R. Recommended Chemical Soil Test Procedures for the North Central Region; North Central Regional Research; Publication No. 221, 1001; Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Missouri Extension: Columbia, MO, USA, 2015; Available online: https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/sera6/PUB/MethodsManualFinalSERA6.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- North Dakota Agricultural Weather Network. North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, USA. 2. Available online: https://ndawn.ndsu.nodak.edu/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- The Statistical Analysis System, SAS. Data Quality Acceleratorjo System Requirements for SAS® 9.4 Foundation for Microsoft Windows; SAS Inst. Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.sas.com/content/dam/SAS/documents/technical/training/ko/ko_kr-94-sreq32.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Cihacek, L.; Senturklu, S.; Landblom, D.G. Mineral N Cycling in an Integrated Crop-Grazing System. In The Dickinson Research Extension Center Annual Report; Dickinson Research Extension Center: Dickinson, ND, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/sites/default/files/2022-10/33.%20Nitrogen%20mineralization_Cihacek%20et%20al.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Alghamdi, R.; Cihacek, L.; Landblom, D.; Senturklu, S. Soil Health Using Haney Biological Analysis in Calcareous Soils in Semi-Arid Environments. In Proceedings of the ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meeting, St. Louis, MO, USA, 29 October–1 November 2023; Available online: https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2023am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/153051 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Landblom, D.; Senturklu, S.; Cihacek, L. Effect of Drought and Subsequent Precipitation (2016–2020) on Soil pH, Microbial Biomass, and Plant Nutrient Change in the Semi-Arid Region of Western North Dakota, USA. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 April 2024; Available online: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU24/EGU24-7094.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Conceição, P.C.; Dieckow, J.; Bayer, C. Combined role of no tillage and cropping systems in soil carbon stocks and stabilization. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 129, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobley, E.U.; Honermeier, B.; Don, A.; Gocke, M.I.; Amelung, W.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Decoupling of subsoil carbon and nitrogen dynamics after long-term crop rotation and fertilization. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Kaiyuan, L. Spatial-aware SAR-optical time-series deep integration for crop phenology tracking. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 276, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notz, I.; Topp, C.F.; Schuler, J.; Alves, S.; Gallardo, L.A.; Dauber, J.; Haase, T.; Hargreaves, P.R.; Hennessy, M.; Iantcheva, A.; et al. Transition to legume-supported farming in Europe through redesigning cropping systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzler, L.; van Apeldoorn, D.F.; Pellegrini, F.; Antichi, D.; Barberi, P.; Rossing, W.A.H. Curent research on the ecosystem service potential of legume inclusive cropping systems in Europe. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, S.A.; Bremner, J.M. Effect of soil mesh-size on estimation of mineralizable nitrogen in soils. Nature 1964, 202, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, D.R. Nitrogen availability indices. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2, Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; Agronomy 9; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America and American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, L.G.; Meisinger, J.J. Nitrogen availability indices. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2, Microbiological and Biochemical Properties; SSSA Book Series No. 5; Weaver, R.W., Angle, S., Bottomley, P., Bezdicek, D., Smith, S., Tabatabai, A., Wollum, A., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 951–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.M.; Jastrow, J.D. Mycorrhizal Fungi Influence Soil Structure. In Arbuscular Mycorrhizas: Physiology and Function; Kapulnik, Y., Douds, D.D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihacek, L.; Augustin, C.; Buetow, R.R.; Landblom, D.G.; Alghamdi, R.; Senturklu, S. What is Soil Acidity? In NDSU Extension Extending Knowledge. SF2012; North Dakota State University: Fargo, ND, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/sites/default/files/2024-05/sf2012.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Landblom, D.G.; Senturklu, S.; Cihacek, L.; Brevik, E. Effect of Five-Year Dry Cycle and Drought on Crop Rotation and Soil Physical and Microbial Property Changes for the Period 2016–2020 in Western North Dakota; Annual Report of the Dickinson Research Extension Center; Dickinson Research Extension Center: Dickinson, ND, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/sites/default/files/2022-10/Effect%20of%20HRSW-5Crop%20Rotation-Crp%20Prod_V4%20FINAL_8-23-17.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Schlegel, A.J.; Assefa, Y.; Haag, L.A.; Thompson, C.R.; Stone, L.R. Long-term tillage on yield and water use of grain sorghum and winter wheat. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittelkow, C.M.; Liang, X.; Linquist, B.A.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Lee, J.; Lundy, M.E. Productivity limits and potentials of the principles of conservation agriculture. Nature 2015, 517, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusinamhodzi, L.; Corbeels, M.; Wijk, M.T.V.; Rufino, M.C.; Nyamangara, J.; Giller, K.E. A meta-analysis of long-term effects of conservation agriculture on maize grain yield under rain-fed conditions. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 31, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture; USDA. National Agricultural Statistics Service North Dakota Field Office County Extension Offices. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/North_Dakota/index.php (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Landblom, D.G.; Senturklu, S.; Cihacek, L.; Steffan, J. Effect of Extreme Drought on Crop Rotation and Soil Physical and Microbial Property Changes for the period 2016–2019 in Western North Dakota. In Annual Report of the Dickinson Research Extension Center; Dickinson Research Extension Center: Dickinson, ND, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/sites/default/files/2022-10/Effect%20of%20Drought-CropRotation-MicrobialChange%202016-2019_FINAL_3-23-2020.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- McDaniel, M.D.; Middleton, T.A. Putting the soil health principles to the test in Iowa. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2024, 88, 2238–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmer, M.R.; Jin, V.L.; Wienhold, B.J.; Becker, S.M.; Varvel, G.E. Long-term rotation diversity and nitrogen effects on soil organic carbon and nitrogen stocks. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2020, 3, e20055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, D.W. North Dakota Fertilizer Recommendation Tables. In NDSU Extension Bulletin SF882; North Dakota State University: Fargo, ND, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/sites/default/files/2023-10/sf882.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

| Year/ Sequence | Crop(s) | Species Mix | Seeding Rate | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Cropping | ||||

| 1–5 | Hard Red Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | 100% | 105 kg ha−1 | |

| Rotation Cropping | ||||

| 1 | Hard Red Spring Wheat | 100% | 105 kg ha−1 | |

| 1–2 | Dual Cover Crop: | Seeded September 10–15 after wheat harvest. Harvested for hay during the first two weeks the following June. | ||

| -Triticale (Triticale hexaploid) | 78% | 89.7 kg ha−1 | ||

| -Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa L.) | 22% | 24.7 kg ha−1 | ||

| 2 | Seven Specie Cover Crop Mix: | Residual vegetation from harvested hay crops terminated with glyphosate. Cover crops seeded in June and seasonal growth grazed in August–September time frame. Seeded crop percentage determined by crop seed size. | ||

| -Field pea (Pisum sativum arvense L.) | 40% | |||

| -Oat (Avena sativa L. var. Everleaf) | 40% | |||

| -Hairy vetch | 10% | |||

| -Canola (Brassica napus L.) | 2% | |||

| -Kale (Brassica napus L. var. pabularia) | 2% | |||

| -Turnip (Brassica rapa L. var. rapa) | 2% | |||

| -Sunflower (Helianthus annus L.) | 4% | |||

| 3 | Silage Corn (Zea mays L.) | 100% | 46,930–49,400 plants ha−1 | 95-day maturity variety seeded in mid-May. |

| 4 | Field pea (Pisum sativum L. var. Arvika) and forage barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. Stockford) | 60% 40% | 27.2 kg ha−1 18.1 kg ha−1 | Seeded in May/June time frame. |

| 5 | Sunflower | 100% | 46,930–49,400 plants ha−1 | Seeded in mid-May/June time frame. |

| Grain Yield and Quality | HRSW CTRL 1 | HRSW ROT 2 | SEM 3 | p-Value 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trt | Yr | Trt × Yr | ||||

| First 6 Years | ||||||

| Yields, kg ha−1 | 2601 | 2702 | 122 | ns | <0.001 | <0.10 |

| Test Wt., kg | 136.7 | 135.7 | 1.23 | ns | <0.01 | ns |

| Protein, % | 13.9 | 13.4 | 0.37 | <0.10 | <0.001 | ns |

| Second 6 Years | ||||||

| Yields, kg ha−1 | 1823 | 1992 | 86.3 | ns | <0.05 | ns |

| Test Wt., kg | 136.4 | 135.7 | 0.54 | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| Protein, % | 11.9 | 12.9 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| 12 Years | ||||||

| Yields, kg ha−1 | 2212 | 2347 | 79.8 | ns | <0.001 | <0.10 |

| Test Wt., kg | 136.6 | 135.7 | 0.59 | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| Protein, % | 12.9 | 13.2 | 0.25 | ns | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| Economic Factor | HRSW CTRL 1 | HRSW ROT 2 | SEM 3 | p-Value 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trt | Yr | Trt × Yr | ||||

| First 6 Years | ||||||

| Input Cost, USD Ha−1 | 455.82 | 413.72 | 1.91 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gross Return, USD Ha−1 | 597.38 | 596.93 | 66.61 | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| Net Return, USD Ha−1 | 141.56 | 183.21 | 67.47 | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| Second 6 Years | ||||||

| Input Cost, USD Ha−1 | 392.79 | 380.76 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gross Return, USD Ha−1 | 398.08 | 432.38 | 37.07 | ns | <0.01 | ns |

| Net Return, USD Ha−1 | 57.25 | 69.22 | 73.28 | ns | <0.05 | ≤0.05 |

| 12 Years | ||||||

| Input Cost, USD Ha−1 | 424.31 | 397.24 | 0.96 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gross Return, USD Ha−1 | 497.73 | 514.75 | 49.46 | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| Net Return, USD Ha−1 | 99.42 | 126.22 | 68.10 | ns | <0.001 | ns |

| HRSW Culture | Soil Test Nitrate-N (kg ha−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Crop | Post-Crop | Difference | |

| HRSW-CTRL | 48.3 | 43.6 | 5.4 |

| HRSW-ROT | 55.4 | 33.6 | 19.3 |

| p-value | ns | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Management Treatment | Soil Test Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH a | Organic Matter (g kg−1) | NO3-N (kg ha−1) | Olsen-P (mg kg−1) | K (mg kg−1) | SO4-S (kg ha−1) | Cl (kg ha−1) | |

| HRSW-CRTL | 5.85 ± 0.48 | 36 ± 10.1 | 39.4 ± 20.4 | 21.5 ± 7.5 | 348 ± 153 | 37.3 ± 17.3 | 41.7 ± 27.2 |

| HRSW-ROT | 6.07 ± 0.67 | 40 ± 10.4 | 40.8 ± 23.4 | 26.2 ± 9.9 | 389 ± 180 | 38.5 ± 13.5 | 52.7 ± 34.2 |

| p TRT | <0.05 | <0.01 | ns | <0.01 | <0.10 | ns | <0.10 |

| p YR | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| p TRT×YR | ns | <0.01 | <0.10 | ns | <0.005 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Nitrogen Source | Grazed Crop 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CORN | PEA/BLY | C/CROP | |

| Animal Number | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Crop Grazing Days | 72 | 30 | 15 |

| Manure | |||

| Estimated DM Manure Production, kg ha−1 | 546 | 228 | 114 |

| Estimated DM Manure N, kg ha−1 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Estimated DM Manure Remaining after N Volatilization Loss of (45%) | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Urine | |||

| Estimated Annual Urine Patch N, kg ha−1 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Daily Urine Patch Volume, l | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Daily N, g/ll | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Annual Urine Patch N, kg | 4.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| Annual Urine Patch 13% NH3 Loss, g | 6.4 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| Annual Urine Patch 13% NH3 Loss, g ha−1 | 15.8 | 6.6 | 3.3 |

| Annual Urine Patch 2% N2O Loss, g | 9.8 | 4.1 | 2.0 |

| Annual Urine Patch 2% N2O Loss, g ha−1 | 24.3 | 10.1 | 5.0 |

| Annual Urine Patch 20% NH3 Leaching, kg | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Annual Urine Patch 20% NH3 Leaching, kg ha−1 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Annual Urine Patch 41% NH3 Leaching, kg | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Annual Urine Patch 41% NH3 Leaching, kg ha−1 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Annual Urine Patch 26% N Soil Immobilization, kg | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Annual Urine Patch 26% N Soil Immobilization, kg ha−1 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Total Urine Patch N Leaching, Forage Uptake, and Soil Immobilization, kg | 4.3 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Total Urine Patch N Leaching, Forage Uptake, and Soil Immobilization, kg ha−1 | 10.5 | 4.4 | 2.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Senturklu, S.; Landblom, D.; Cihacek, L.J. Effect of a Long-Term Integrated Multi-Crop Rotation and Cattle Grazing on No-Till Hard Red Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Production, Soil Health, and Economics. Agriculture 2026, 16, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010073

Senturklu S, Landblom D, Cihacek LJ. Effect of a Long-Term Integrated Multi-Crop Rotation and Cattle Grazing on No-Till Hard Red Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Production, Soil Health, and Economics. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenturklu, Songul, Douglas Landblom, and Larry J. Cihacek. 2026. "Effect of a Long-Term Integrated Multi-Crop Rotation and Cattle Grazing on No-Till Hard Red Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Production, Soil Health, and Economics" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010073

APA StyleSenturklu, S., Landblom, D., & Cihacek, L. J. (2026). Effect of a Long-Term Integrated Multi-Crop Rotation and Cattle Grazing on No-Till Hard Red Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Production, Soil Health, and Economics. Agriculture, 16(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010073