Dual Role of Copper in the Micropropagation of Olive: Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses from Beneficial Growth to Lethal Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Introduction and Stabilization In Vitro of cv. Moraiolo Shoot Culture

2.2. Cu Experiment

2.3. Pigment Determination

2.4. Hydrogen Peroxide, Malondialdehyde, Antioxidants, and Proline Quantifications

2.4.1. Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

2.4.2. The Malondialdehyde (MDA)

2.4.3. The Ascorbic Acid (AsA)

2.4.4. Glutathione (GSH)

2.4.5. Proline

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

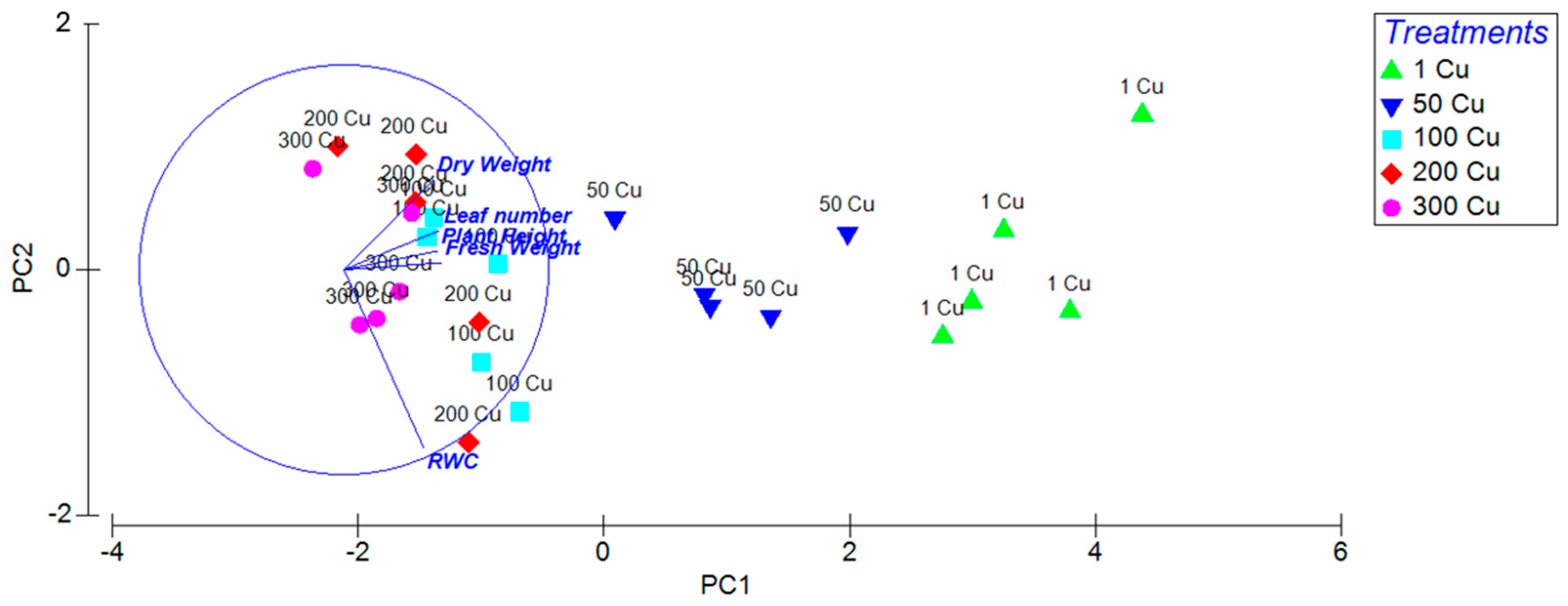

3.1. General Effects of Cu on Growth of In Vitro Olive Shoots

3.2. Morphological Traits of In Vitro Olive Shoots Under Different Cu Concentrations

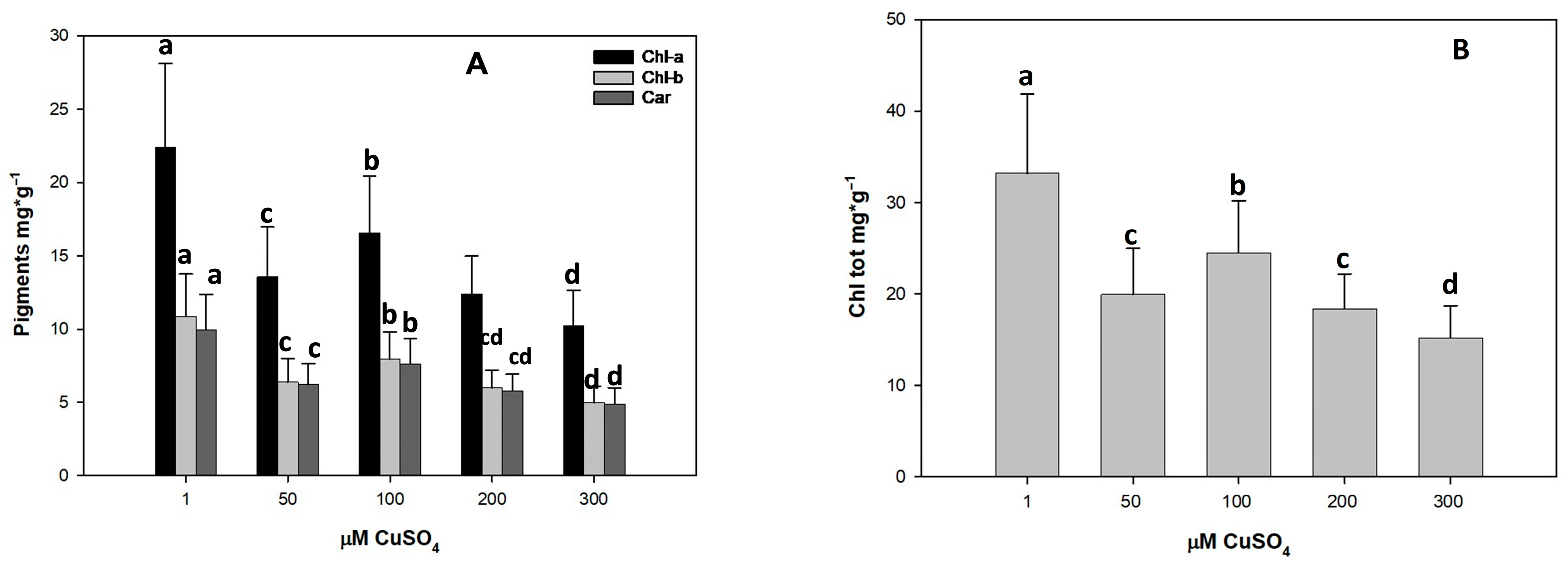

3.3. Effect of Cu Toxicity on Photosynthetic Pigments

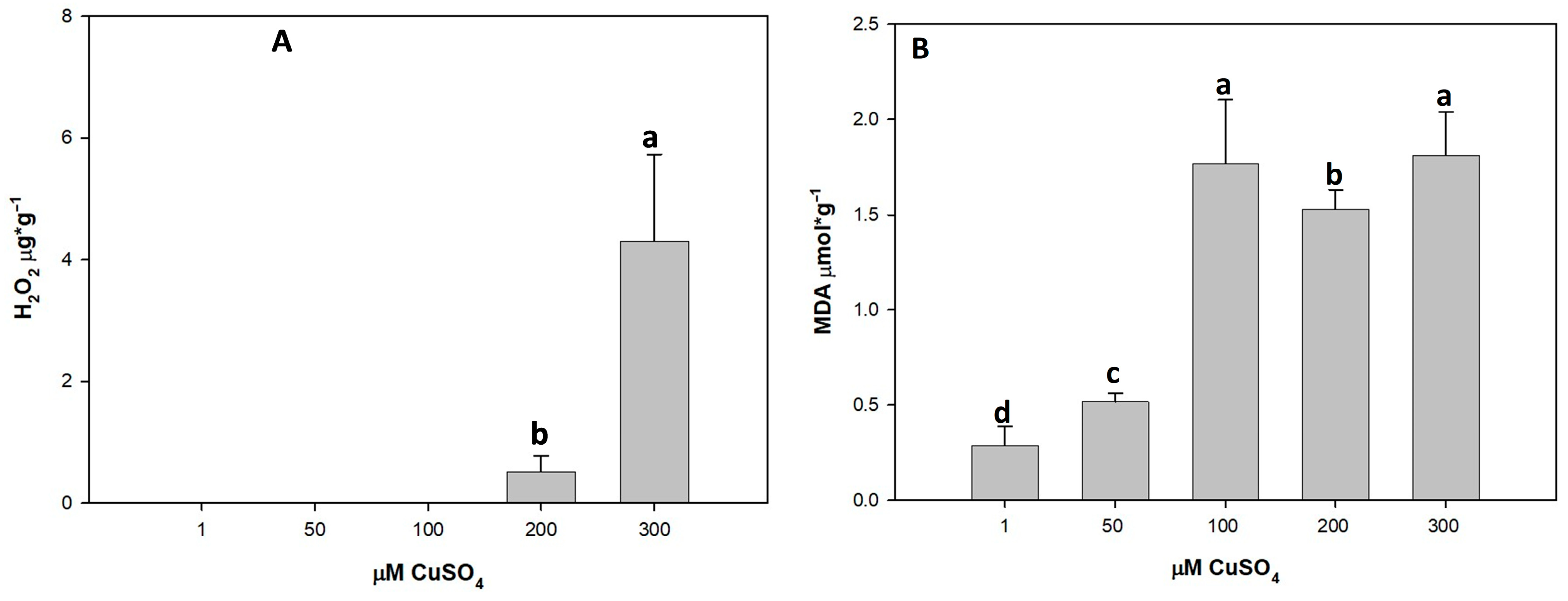

3.4. Effect of Cu Toxicity on Oxidative Stress Markers

3.4.1. Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

3.4.2. Impact of Cu on MDA Levels

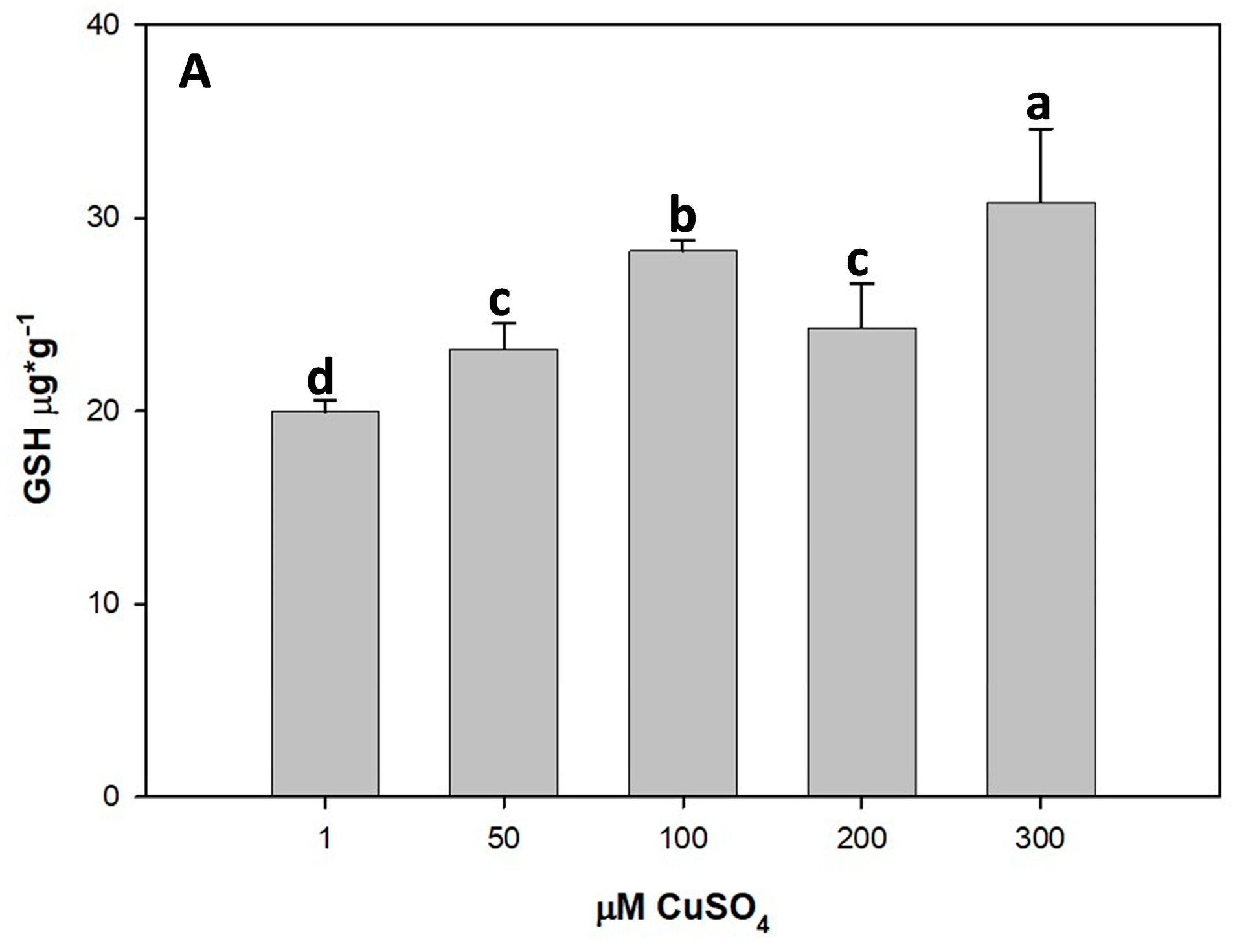

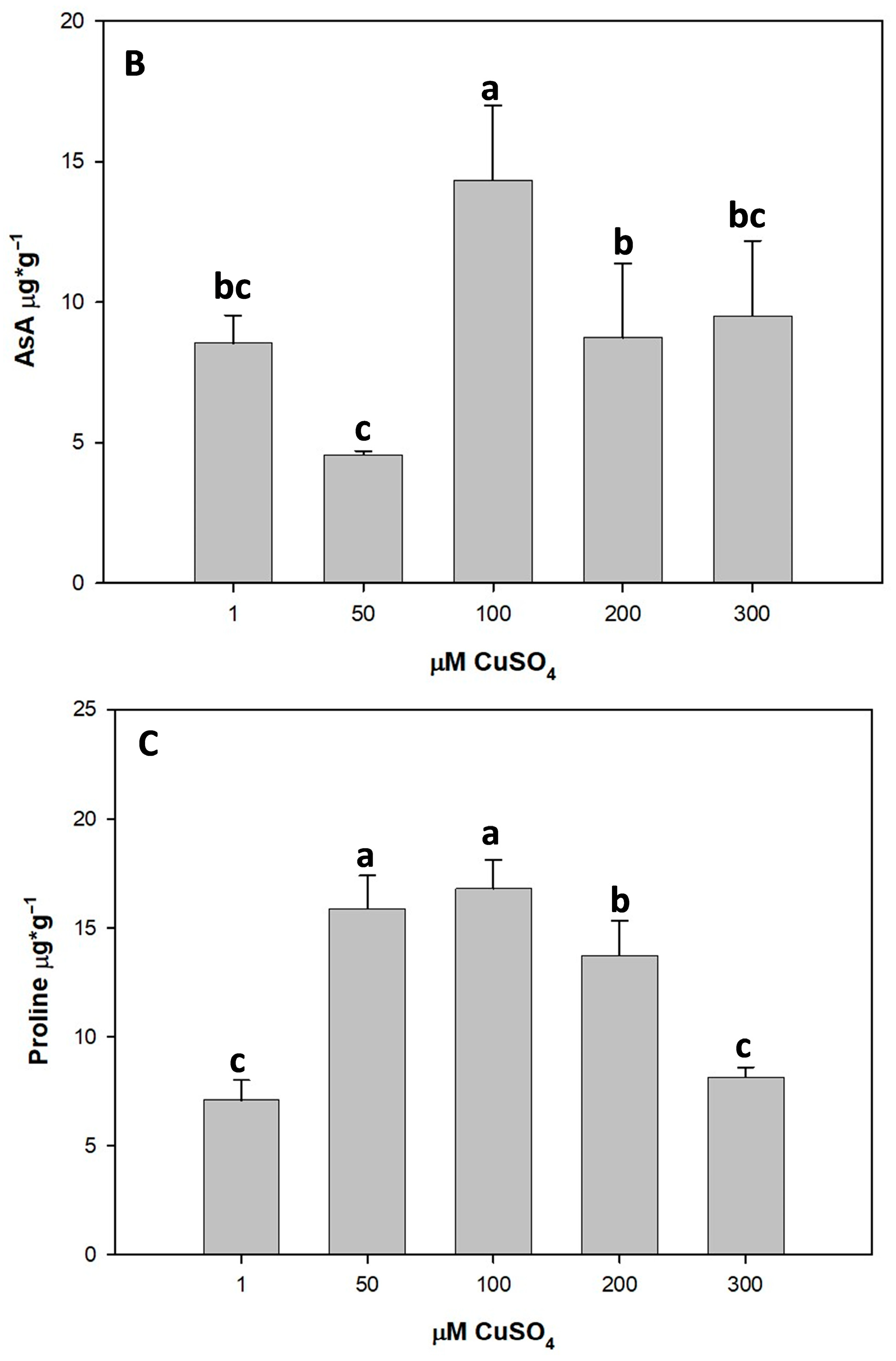

3.5. Effect of Cu Toxicity on Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants

3.5.1. Impact of Cu on GSH Content

3.5.2. Ascorbic Acid (AsA)

3.5.3. Effect of Cu Stress on Proline Content

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zohary, D.; Spiegel-Roy, P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science 1975, 187, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avramidou, E.V.; Boutsios, S.; Korakaki, E.; Malliarou, E.; Solomou, A.; Petrakis, P.V.; Koubouris, G. Olive, a monumental tree; multidimensional perspective from origin to sustainability. In Economically Important Trees: Origin, Evolution, Genetic Diversity and Ecology. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Uthup, T.K., Karumamkandathil, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Datasets FAO Olive and Olive Oil Production. 2023. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Lambardi, M.; Rugini, E. Micropropagation of olive (Olea europaea L.). In Microprop-Agation of Woody Trees and Fruits, Forestry Sciences; Jain, S.M., Ishii, K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regni, L.; Brunori, A.; Mairech, H.; Testi, L.; Proietti, P. Multifunctionality of olive groves. In The Olive Botany and Production; Fabbri, A., Baldoni, L., Caruso, T., Famiani, F., Eds.; CAB International: Wellingford, UK, 2023; pp. 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.S.; Barbosa, J.T.P.; Fernandes, A.P.; Lemos, V.A.; dos Santos, W.N.L.; Korn, M.G.A.; Teixeira, L.S.G. Multi-element determination of Cu, Fe, Ni and Zn content in vegetable oils samples by high-resolution continuum source atomic absorption spectrometry and microemulsion sample preparation. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yruela, I. Copper in plants. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 17, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Razzaq, A.; Mehmood, S.S.; Zou, X.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.; Xu, J. Impact of Climate Change on Crops Adaptation and Strategies to Tackle Its Outcome: A Review. Plants 2019, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Díaz-Espejo, A.; Barragán, V.; Luque-Cobija, M.; Ruiz, L.; Rodríguez, P.; Hernández, M.J.; Navarro, M.; Muñoz, M.; Shabala, S.; et al. Advancements in Water-Saving Strategies and Crop Adaptation to Drought: A Comprehensive Review. Plants 2025, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elazab, D.; Lambardi, M.; Capuana, M. In Vitro Culture Studies for the Mitigation of Heavy Metal Stress in Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luka, M.F.; Akun, E. Investigation of trace metals in different varieties of olive oils from northern Cyprus and their variation in accumulation using ICP-MS and multivariate techniques. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, B.; Yasemin, B.K.; Selcuk, Y. Comparison of extraction induced by emulsion breaking, ultrasonic extraction and wet digestion procedures for determination of metals in edible oil samples in Turkey using ICP-OES. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabier, T.; Luis, D.M.; Pablo, H.P. Determination of arsenic species distribution in extra virgin olive oils from arsenic-endemic areas by dimensional chromatography and atomic spectroscopy. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 66, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, F.; Hussain, A.; Fariduddin, Q. Hydrogen peroxide modulate photosynthesis and antioxidant systems in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants under copper stress. Chemosphere 2019, 230, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkleij, J.A.C.; Lolkema, P.C.; De Neeling, A.L.; Harmens, H. Heavy metal resistance in higher plants: Biochemical and genetic aspects. In Ecological Responses to Environmental Stresses; Rozema, J., Verkleij, J.A.C., Eds.; Tasks for Vegetation Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Li, Z.H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.Y.; Kang, Q.; Niu, D.D. Gibberellic acid application on biomass, oxidative stress response, and photosynthesis in spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) seedlings under copper stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 53594–53604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeu–Moreno, A.; Mas, A. Effect of copper exposure in tissue cultured Vitis vinifera. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 2519–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, B.; Nayak, P.K. Study of copper phytotoxicity on in vitro culture of Musa acuminata cv Bantala. J. Agric. Biotech. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 3, 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Habahbeh, K.A.; Al-Nawaiseh, M.B.; Al-Sayaydeh, R.S.; Al-Hawadi, J.S.; Albdaiwi, R.N.; Al-Debei, H.S.; Ayad, J.Y. Long-term irrigation with treated municipal wastewater from the Wadi Musa region: Soil heavy metal accumulation, uptake and partitioning in olive trees. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzaid, E.; El-Sayed, E.S.N.; Mohamed, E.S.A.; Youssef, M. Molecular Analysis of Drought Tolerance in Guava Based on In Vitro PEG Evaluation. Trop. Plant Biol. 2016, 9, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, P.; Schiff, S.; Santandrea, G.; Bennici, A. Response of in vitro cultures of Nicotiana tabacum L. to copper stress and selection of plants from Cu-tolerant callus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 1998, 53, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aref, H.M.; Hamada, A.M. Genotypic differences and alterations of protein patterns of tomato explants under copper stress. Biol. Plant. 1998, 41, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, B.; Goswami, B.C. Effect of zinc and copper on growth and regenerating cultures of Citrus reticulata Blanco. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 5, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, E. Micropropagation of Ailanthus altissima and in vitro heavy metal tolerance. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mayahi, A.M.W. Effect of copper sulphate and cobalt chloride on growth of the in vitro culture tissues for date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cv. Ashgar. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2014, 9, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- González-Torres, P.; Puentes, J.G.; Moya, A.J.; La Rubia, M.D. Comparative study of the presence of heavy metals in edible vegetable oils. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambardi, M.; Ozudogru, E.A.; Roncasaglia, R. In vitro propagation of olive (Olea europaea L.) by nodal segmentation of elongated shoots. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 11013, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugini, E. In vitro propagation of some olive (Olea europaea sativa L.) cultivars with different root-ability, and medium development using analytical data from developing shoots and embryos. Sci. Hortic. 1984, 24, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, D.; Pandey, A.; Choudhary, M.K.; Datta, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, N. Comparative proteomics analysis of differentially expressed proteins in chickpea extracellular matrix during dehydration stress. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2007, 6, 1868–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexieva, V.; Sergiev, I.; Mapelli, S.; Karanov, E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress markers in pea and wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, M. An improved method for determination of L-ascorbic acid and L-dehydroascorbic acid in blood plasma. Clin. Chim. Acta 1980, 103, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.Y.; Charles, S.A.; Halliwell, B. Glutathione and ascorbic acid in spinach (Spinacea oleracea) chloroplasts: The effect of hydrogen peroxide and of paraquat. Biochem. J. 1983, 210, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlak, J.; Lindsay, R.H. Estimation of total, protein-bound and non-protein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968, 25, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.E.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhead, J.L.; Gogolin Reynolds, K.A.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Cohu, C.M.; Pilon, M. Copper homeostasis. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrees, M.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Abbas, F.; Farid, M.; Zia-Ur-Rehman, M.; Irshad, M.K.; Bharwana, S.A. The effect of excess copper on growth and physiology of important food crops: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 8148–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisam, W.M.; Abdel Aal, A.H.; Khodair, O.A. Muhammad Youssef In vitro performance of two banana cultivars under copper stress Assiut. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 51, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, D.M.; da Silva, A.B.; Mantovani, J.R.; Magalhães, P.C.; de Souza, T.C. Root morphology and leaf gas exchange in Peltophorum dubium (Spreng.) Taub. (Caesalpinioideae) exposed to copper-induced toxicity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 121, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mendoza, D.; Gil, F.E.; Escoboza-Garcia, F.; Santamaría, J.M.; Zapata-Perez, O. Copper stress on photosynthesis of black mangle (Avicennia germinans). An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2013, 85, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Tran, C.D.; Nguyen, K.H.; Chu, H.D.; Watanabe, Y.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Mohsin, S.M.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.S.P. Insights into acetate-mediated copper homeostasis and antioxidant defense in lentil under excessive copper stress. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.L.; Chen, Y.A.; Chen, L.M.; Liu, Z.H. Effect of copper on peroxidase activity and lignin content in Raphanus sativus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Narula, A.; Sharma, M.; Srivastava, P.S. Effect of copper and zinc on growth, secondary metabolite content and micropropagation of Tinospora cordifolia: A medicinal plant. Phytomorphology 2003, 53, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yurekli, F.; Porgali, Z.B. The effects of excessive exposure to copper in bean plants. Acta Biol. Cracoviensia Ser. Bot. 2006, 48, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Panou-Filotheou, H.; Bosabalidis, A.M.; Karataglis, S. Effects of copper toxicity on leaves of oregano (Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum). Ann. Bot. 2001, 88, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porgali, Z.B.; Yurekli, F. Salt stress-induced alterations in proline accumulation, relative water content and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in salt sensitive Lycopersicon esculentum and L. pennellii. Acta Bot. Hung. 2005, 47, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Yusuf, M.; Fariduddin, Q. Seed treatment with H2O2 modifies net photosynthetic rate and antioxidant system in mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) plants. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 62, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Armin, S.M.; Qian, P.; Xin, W.; Li, H.Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.S.P. Hydrogen peroxide priming modulates abiotic oxidative stress tolerance: Insights from ROS detoxification and scavenging. Front Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaeda, T.; Rahman, M.; Liping, X.; Schoelynck, J. Hydrogen peroxide variation patterns as abiotic stress responses of Egeria densa. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 855477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, Q. Oxidative and some antioxidant systems in acid rain–treated bean plants: Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, H.; Jouili, H.; Geitmann, A.; El Ferjani, E. Effect of copper excess on H2O2 accumulation and peroxidase activities in bean roots. Acta Biol. Hung. 2008, 59, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shan, X.; Wen, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z. Responses of antioxidative enzymes to accumulation of copper in a copper hyperaccumulator Commelina communis. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 47, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Yu, L.L.; Li, C.Y.; Zhang, M.M.; Zhang, X.Q.; Fang, Y.X.; Xue, D.W. Genome-wide identification of barley NRAMP and gene expression analysis under heavy metal stress. Biotechnol. Bull. 2022, 38, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Anjani, K.; Srivastava, N. In vitro evaluation of excess copper affecting seedlings and their biochemical characteristics in Carthamus tinctorius L. (variety PBNS-12). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2016, 22, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pardo, B.; Fernández-Pascual, M.; Zornoza, P. Copper microlocalisation and changes in leaf morphology, chloroplast ultrastructure and antioxidative response in white lupin and soybean grown in copper excess. J. Plant Res. 2014, 127, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.; Anee, T.I.; Parvin, K.; Nahar, K.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M. Regulation of ascorbate-glutathione pathway in mitigating oxidative damage in plants under abiotic stress. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagalakshmi, N.; Prasad, M.N.V. Responses of glutathione cycle enzymes and glutathione metabolism to copper stress in Scenedesmus bijugatus. Plant Sci. 2001, 160, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, S.G.; Tang, Z.J.; Zhao, Y.M.; Li, W. Oxidative damage and antioxidant response caused by excess copper in leaves of maize. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 4378–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Sarwat, M.; Sharma, S. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants and signaling in plants. J. Plant Biol. 2008, 51, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Chaouch, S.; Han, Y.I.; Neukermans, J.; Marquez-Garcia, B.; Queval, G.; Foyer, C.H. Glutathione in plants: An integrated overview. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 454–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, S.S.; Chu, H.H.; Chan-Rodriguez, D.; Punshon, T.; Vasques, K.A.; Salt, D.E.; Walker, E.L. Arabidopsis thaliana Yellow Stripe1-Like4 and Yellow Stripe1-Like6 localize to internal cellular membranes and are involved in metal ion homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thounaojam, T.C.; Panda, P.; Mazumdar, P.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, G.D.; Sahoo, L.; Sanjib, P. Excess copper induced oxidative stress and response of antioxidants in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 53, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, M.E.; Tourky, S.M.N.; Elsharkawy, S.E.A. Symptomatic parameters of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system in Phaseolus vulgaris L. in response to copper or cadmium stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 117, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elazab, D.S.; Ahmed, M.A.I.; El-Mahdy, M.T.; Ahmed, A. Citrus leafminer management: Jasmonic acid versus efficient pesticides. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 40, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azooz, M.M.; Abou-Elhamd, M.F.; Al-Fredan, M.A. Biphasic effect of copper on growth, proline, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities of wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Hasaawi) at early growing stage. Am. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 688–694. [Google Scholar]

- Vinod, K.; Awasthi, G.; Chauhan, P.K. Cu and Zn tolerance and responses of the biochemical and physiochemical system of wheat. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 8, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment (µM) | H (cm) | #L | FW (g) | DW (g) | RWC (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ±SE | Mean | ±SE | Mean | ±SE | Mean | ±SE | Mean | ±SE | |

| 1 CuSO4 | 8.64 | ±0.09 | 21.4 | ±2.13 | 0.512 | ±0.030 | 0.068 | ±0.018 | 86.676 | ±1.45 |

| 50 CuSO4 | 4.64 | ±0.09 | 11.8 | ±1.68 | 0.298 | ±0.039 | 0.056 | ±0.005 | 80.547 | ±1.92 |

| 100 CuSO4 | 3.36 | ±0.16 | 4.4 | ±0.51 | 0.100 | ±0.007 | 0.026 | ±0.001 | 73.269 | ±3.07 |

| 200 CuSO4 | 3.06 | ±0.19 | 3.6 | ±0.40 | 0.080 | ±0.009 | 0.024 | ±0.002 | 68.403 | ±4.77 |

| 300 CuSO4 | 2.18 | ±0.23 | 3.4 | ±0.40 | 0.055 | ±0.006 | 0.018 | ±0.002 | 67.404 | ±2.53 |

| p-level | *** | * | n.s. | *** | *** | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elazab, D.; Pignattelli, S.; Fascella, G.; Ruta, C.; Lambardi, M. Dual Role of Copper in the Micropropagation of Olive: Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses from Beneficial Growth to Lethal Stress. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242544

Elazab D, Pignattelli S, Fascella G, Ruta C, Lambardi M. Dual Role of Copper in the Micropropagation of Olive: Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses from Beneficial Growth to Lethal Stress. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242544

Chicago/Turabian StyleElazab, Doaa, Sara Pignattelli, Giancarlo Fascella, Claudia Ruta, and Maurizio Lambardi. 2025. "Dual Role of Copper in the Micropropagation of Olive: Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses from Beneficial Growth to Lethal Stress" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242544

APA StyleElazab, D., Pignattelli, S., Fascella, G., Ruta, C., & Lambardi, M. (2025). Dual Role of Copper in the Micropropagation of Olive: Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses from Beneficial Growth to Lethal Stress. Agriculture, 15(24), 2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242544