1. Introduction

According to the data of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations for 2023, apple production in all 27 countries of the European Union amounted to 12.06 million tonnes harvested from over 471,870 hectares. This represents 12.4% of the global production volume. Poland remains the leading player in the region with 3.9 million tonnes of apples harvested from 150,000 hectares in 2023 [

1].

In Poland, apple production plays a more prominent role in overall agricultural output than in other major European producers. For instance, from 2019 to 2021, it accounted for 3.0% of Poland’s total agricultural production value, compared to 1.7% in Italy and just 0.2% in Germany [

2]. Whilst Polish apple production is predominantly oriented towards processing, with over half of the harvested fruit annually directed to this sector [

3], there is a growing emphasis on dessert apple cultivation, which offers higher profitability but requires expanded domestic and export markets [

2]. This shift is reflected in evolving structures of varieties grown: during 2013–2016, the four dominant cultivars by planted area were ‘Idared’ (18.5%), ‘Šampion’ (10.6%), ‘Jonagold’ (9.7%) and ‘Ligol’ (7.7%), with ‘Gala’ comprising only 3.8% [

4]. However, the latest survey conducted in 2023 by the National Association of Fruit and Vegetable Producer Groups (KZGPOiW, Poland) as part of the ‘liczymyjablka.pl’ project [

5] indicates an increase in dessert-oriented cultivars with strong export potential. Consequently, ‘Red Jonaprince’ now occupies 18.4%, ‘Gala’ 16.2% and ‘Šampion’ 14.4% of the planted area. This emphasises growers’ interest in high-quality, market-driven cultivars—including the ‘Gala’ sport investigated herein.

However, approximately half of Poland’s area is covered by light-textured soils with a mechanical composition of loose, weakly loamy or loamy sand, including nearly a 35% share of podzolic soils of low agricultural suitability. Such soils are characterised by a loose structure, drought susceptibility, high acidity, low organic matter content and poor nutrient sorption [

6,

7,

8]. This limits the possibilities for establishing apple orchards, especially intensive, high-yielding ones with trees grafted onto dwarf rootstocks and planted at high density, which require fertile soils with a high water holding capacity [

9]. Additional challenges include increasingly frequent drought periods over recent decades, resulting in prolonged water deficits for crops [

10], as well as the EU-driven imperative to reduce mineral fertiliser consumption [

11].

Moreover, fruit production in Poland is not evenly distributed across the country but is concentrated in a few centres such as the Grójec-Warka, Sandomierz, Opole Lubelskie and Skierniewice regions, where fruit trees are grown in monoculture or under very limited crop rotation. Consequently, there have been common problems with replant disease, which early research had already identified almost three decades ago [

12]. This is a complex and still not fully explained syndrome that occurs when a new orchard is established on a site where apple trees had previously been grown. It is thought to involve physical factors, such as soil depletion and degradation, as well as biotic factors, including plant-parasitic nematodes and soil-borne pathogens [

13,

14]. The release of phytotoxic compounds through the decomposition of root residues from the previous orchard has been reported as another contributing factor [

15].

In this context, biochar could be a promising solution for improving the productivity of apple orchards. This material, defined as a man-made product of biomass heating at relatively low temperatures (<700 °C) in a closed system with low atmospheric oxygen concentration or in its absence [

16], has gained widespread interest as a soil conditioner. Its properties and applications in agriculture were summarised in a review by Das et al. [

17]. Briefly, the potential advantages of using biochar in crops include increased water retention in the soil [

18,

19] and mitigating the negative effects of drought on plants [

20], reducing nutrient losses to the environment [

21,

22,

23] mostly by improving their sorption in the soil [

24,

25], counteracting soil erosion [

26], loosening excessively compacted soils [

27,

28] and stimulating soil microbial activity [

29] as well as reducing replanting disease [

30,

31,

32]. Biochar itself also possesses high fertiliser value [

33,

34,

35], provided it is not purified of mineral components [

36].

However, the effectiveness of biochar in agricultural applications is highly dependent on both the feedstock and the production technology. These factors govern the basic physical and chemical properties of the resulting biochar. The feedstock, as well as pyrolysis temperature and duration, determines the mineral content of the product [

33,

34,

35,

37,

38], its specific surface area [

39,

40,

41], porosity [

39,

42] and bulk density [

43,

44,

45]. Consequently, the effects of different biochar types on crops can vary considerably, even when applied at the same rate [

46,

47].

Although the growth- and yield-stimulating effect of biochar has been confirmed by hundreds of individual studies and several derived meta-analyses [

48,

49,

50], the vast majority of these works concerned annual crops only. Few similar studies have been performed on fruit crops, with their findings being rather inconclusive. In apple production specifically, Li et al. [

51] applied biochar produced from pruned apple branches at rates of 2–12 kg tree

−1 (surface-applied) in a >20-year-old commercial orchard and recorded the highest fruit yield and quality at an intermediate dose of 6 kg tree

−1, which was considered optimal. The authors concluded that biochar holds particular promise for sustaining productivity in ageing plantings. In contrast, Ventura et al. [

22] incorporated 10 t ha

−1 of biochar derived from orchard pruning residues into the soil profile of an established apple planting and observed no significant effects on fruit yield, leaf chlorophyll content or leaf dry mass. Similarly, Eyles et al. [

52] applied a high rate (47 t ha

−1) of biochar produced from green waste (

Acacia spp.), either alone or co-applied with compost, on a fertile soil already rich in organic matter and managed under intensive irrigation and fertigation. Under these conditions, neither treatment significantly affected yield nor fruit quality, although trunk circumference increased significantly when biochar was combined with compost, indicating potential synergy. Khorram et al. [

53] likewise reported increased trunk diameter following biochar application, both alone and with compost, yet without concomitant improvements in fruit yield or quality. This experiment was conducted under apple replant disease conditions. Finally, von Glisczynski et al. [

54], also working in a replant site, not only failed to detect any yield-stimulating effect of biochar-compost substrate but even recorded reduced tree vigour, suggesting possible negative effects of biochar application.

Furthermore, no detailed assessment has been made of the impact of interactions between biochar and fertilisation on the growing pattern of apple trees in the first season after planting, even though this has a decisive influence on the yields in subsequent years of orchard operation [

55,

56]. Nor have biochar application methods been compared, despite orchard management, unlike the annual cropping system, allowing for its use in various ways both before and after tree planting.

Given the above, the aim of this study was to assess the impact of three methods of biochar application (application before ploughing prior to orchard establishment; application to planting holes; and surface spreading after tree planting) in combination with two fertilisation regimes (the use of compost or mineral nitrogen) on the growth and fruiting potential of apple trees in the first season after orchard establishment. It was hypothesised that biochar, regardless of the method of application, would enhance nutrient use efficiency from both organic and mineral sources, thereby promoting more vigorous initial growth, improving tree resilience to abiotic stresses and increasing the orchard’s fruiting potential for the coming season. The outcomes of this work were expected to provide Polish apple growers with evidence-based guidance on whether, when and how biochar can be integrated into establishment practices to achieve faster canopy development and higher fruiting potential of apple trees.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Layout

A field trial was established in Wieluń, Central Poland (51°13′55″ N 18°31′26″ E), in April 2021. The experimental site featured sandy loam soil formed on limestone, characterised by granulometric composition shown in

Table 1 and the chemical properties given in

Table 2. Monthly meteorological data and the corresponding values of the Selyaninov’s hydro-thermal coefficient (a drought indicator; [

57]) for the months preceding tree planting (January–March 2021) and during their growth, are presented in

Table 3. This study presents results from the first growing season of the field trial.

The experimental orchard was established using high-quality, feathered, bare-root maiden apple trees (

Malus domestica Borkh.) cv. ‘Gala Brookfield Baigent’ grafted onto P 60 rootstock (a semi-dwarf rootstock of Polish breeding with growth vigour intermediate between M9 and M26 [

59]). The maiden trees were obtained from a private nursery ‘JANKOWSKI & SYN’ based in Gąbin, Poland. The nursery material was of uniform quality and characterised by a well-developed canopy with several (8–12) long lateral shoots forming a wide angle with the leader.

The forecrop for the apple orchard was potatoes. Over the preceding few years, the land had been under an annual rotation of potatoes with buckwheat or phacelia, which were used as green manure. The soil had been managed with a plough tillage system. Fruit crops had never been grown there before.

The orchard was established at a spacing of 3 × 1 m in a single-row planting system. After planting, the trees were pruned by cutting back side shoots longer than 50 cm by ⅔ of their length. In May, the emerging flowers were removed manually in order to prevent fruit setting in favour of vegetative growth. Plant protection treatments were performed using approved chemical pesticides in accordance with the needs identified on the basis of regular monitoring. The soil in the 1 m wide tree rows was kept weed-free by spraying with glyphosate, whereas spontaneous vegetation was allowed to grow in the inter-rows and was regularly mowed. The orchard was not irrigated.

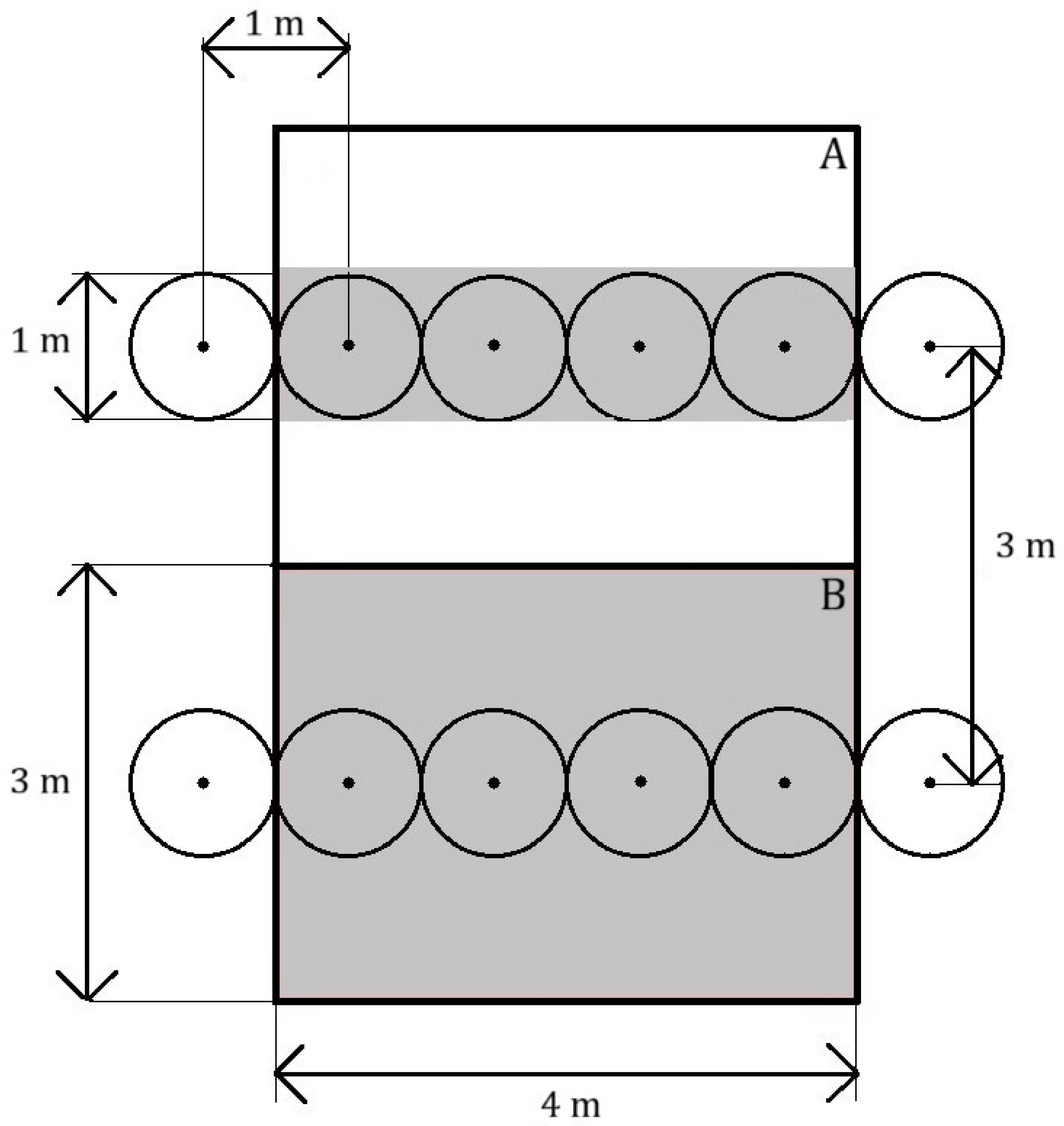

Three methods of biochar application, i.e., plough incorporation, planting-hole application and surface spreading, each in combination with compost or mineral nitrogen fertilisation, were tested against the fertilisers applied singly and an untreated control. This gave a total of nine treatments, each represented by three replicates arranged in a completely randomised design. A single replicate consisted of a plot of four contiguous trees in a row (4 × 1 m). Consecutive replicates were separated by a 4 m gap, equivalent to four tree spaces.

The plough incorporation involved introducing biochar into the soil profile by ploughing to a depth of 20 cm before establishing the orchard. The planting-hole application consisted of pouring it into the hole in which the tree was then planted, whilst the surface application involved spreading biochar evenly in the tree rows and mixing it with the topsoil using a hoe after the orchard had been established. In each treatment, the proportion of biochar per unit area of 10 t ha

−1 (1 kg m

−2) was observed, whereby (i.) in the plough incorporation, it was spread over the entire surface of the experimental plot (tree rows and half of the inter-rows on both sides); (ii.) in the planting-hole application, a dose of 1 kg per tree was used, i.e., a value corresponding to 1 m

2; and (iii.) in the surface application, biochar was used only in the space planned for 1 m wide herbicide strips. This approach was intended to stimulate various possible methods of applying biochar, both before and after the orchard establishment, accounting for differences in material consumption. A diagram comparing the plough incorporation and surface spreading methods of using biochar is presented in

Figure 1.

The biochar used in the study was produced by FLUID S.A., based in Sędziszów, Poland. It was obtained by heating cattle manure at a temperature of approx. 300 °C in a low-oxygen environment. It was applied in powder form. The material contained 1.90% total nitrogen, 0.78% phosphorus and 3.49% potassium, with a dry matter content of 84%. Organic matter accounted for 69% of the dry matter of biochar, and its pH was 9.5.

Compost under the trade name ‘Próchniaczek’ was purchased from the Municipal Waste Management Company (MPO) based in Łódź, Poland. The main substrates used in its production were biodegradable municipal waste and residues from the maintenance of urban green areas. The mineral composition of the compost used is presented in

Table 4. In the relevant treatments, compost was applied at a dose of 67 t ha

−1 before the orchard establishment in a manner analogous to that described for biochar in the plough incorporation.

In the appropriate treatments, mineral nitrogen was applied in two doses after planting the orchard. On the 25 April 2021, 5 g N m−2 was spread in the form of urea, and a month later, 15 g N m−2 was spread in the form of ammonium nitrate. Both nitrogen fertilisers were produced by AZOTY Puławy, Poland. The nitrogen fertilisation was applied only in tree rows in the area of herbicide strips.

The following basic parameters were assessed: (i.) trunk circumference; (ii.) total length of current-year shoots; (iii.) the number of long shoots; (iv.) the number of short shoots; (v.) the number of mixed-type buds; (vi.) leaf area and (vii.) leaf dry matter. The measurements i.–v. were taken during the dormancy period following the first year of tree growth in the orchard. The trunk circumference was measured at a height of 30 cm above the grafting site. Shoots shorter than 20 cm were considered short shoots, while longer ones were considered long shoots. Leaf sampling (measurements vi.–vii.) was carried out in the third decade of August 2021 during the growing season. Fourteen leaves were collected from the middle part of long shoots at half the height of each of the four trees per replicate. The leaves were scanned at 1200 DPI using a Brother DCP-L2622DW scanner. Their surface area was assessed by means of

pliman programme [

60]. The leaf samples were dried at room temperature until a constant weight was achieved (no more water was evaporating) and then weighed using a calibrated and officially legalised electronic laboratory scale with a measurement accuracy of 0.01 g (model RADWAG 1/A2/C/2; RADWAG Electronic Scales, Radom, Poland).

Trunk circumference was converted to trunk cross-sectional area (TCSA) using the formula for the area of a circle. Growth-related fruiting potential was then calculated as the ratio of the number of mixed-type buds to TCSA.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

The primary method used to assess the impact of the studied factors on the evaluated parameters was analysis of variance. The data was checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for variance homogeneity using the Levene test. If both conditions were fulfilled, classical one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, followed by the Tukey HSD test as a post hoc procedure. If the assumption of variance homogeneity was not fulfilled, ANOVA with Welch’s F” correction was used, followed by the Games–Howell post hoc procedure. Non-normal variables were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance by rank.

In addition, parameters for which statistically significant results were obtained through one-way analyses of variance were subjected to multiple linear regression models, broken down by particular fertilisation-related factors. Thus, the explanatory variables were ‘method of biochar application’ (levels: not applied; plough incorporation; planting-hole application; surface application), ‘compost application’ (levels: not applied; applied) and ‘mineral nitrogen fertilisation’ (levels: not applied; applied). These categorical variables were dummy codded, with the absence of each treatment being considered a reference category. For each model applied, III type sum of squares was used.

The normality of model residuals was assessed visually based on a normal Q-Q plot, with the Lilliefors test applied as an adjunctive method. The homoscedasticity of the model residuals was evaluated visually based on plots presenting the residuals and residual squares against the predicted and observed values. The dependent variable ‘ratio of the number of mixed-type buds to trunk cross-sectional area’ had to be converted using the Box-Cox transformation to meet the assumptions of the regression model. The autocorrelation of model residuals was controlled using the Durbin–Watson test, with reference to established critical values [

61]. Outliers were identified using a criterion whereby an observation was considered to be an outlier if its residual exceeded three standard deviations of the model residuals. No observations exceeded this threshold.

The measures of effect size presented for the ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests and multiple regression models were η2 (eta-squared), ε2 (epsilon-squared) and R2, respectively.

Moreover, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the seven basic parameters describing tree growth and fruiting potential. The PCA was based on the correlation matrix. The original variables had been standardised (z-score) before the procedure. Relevance of the analysis had been confirmed by the result of Bartlett’s test (p < 0.001) and value of Keiser–Mayer–Olkin coefficient equal to 0.68.

The significance level of α ≤ 0.05 was adopted for testing the hypotheses. The PQStat v.1.8.6 package (PQStat Software, Poznań, Poland) was used for all the statistical calculations.

3. Results

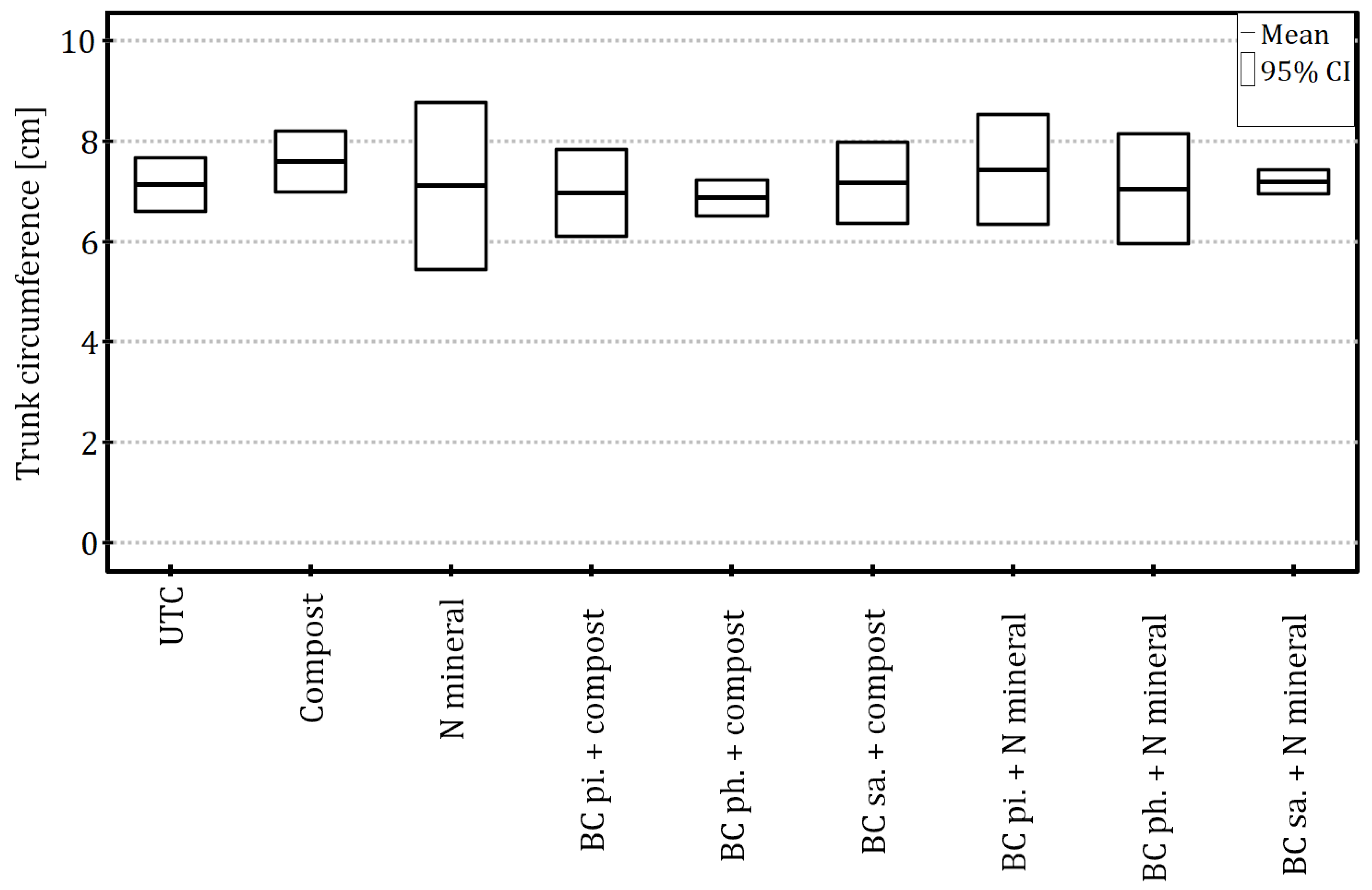

The growth of the apple trees, expressed both as the trunk circumference (ANOVA:

F8,18 = 1.13,

p = 0.39 and η

2 = 0.34) and the total length of the current-year shoots (ANOVA:

F8,18 = 1.34,

p = 0.29 and η

2 = 0.37), was not significantly affected by biochar and fertilisation combinations, despite relatively large effect size estimates (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

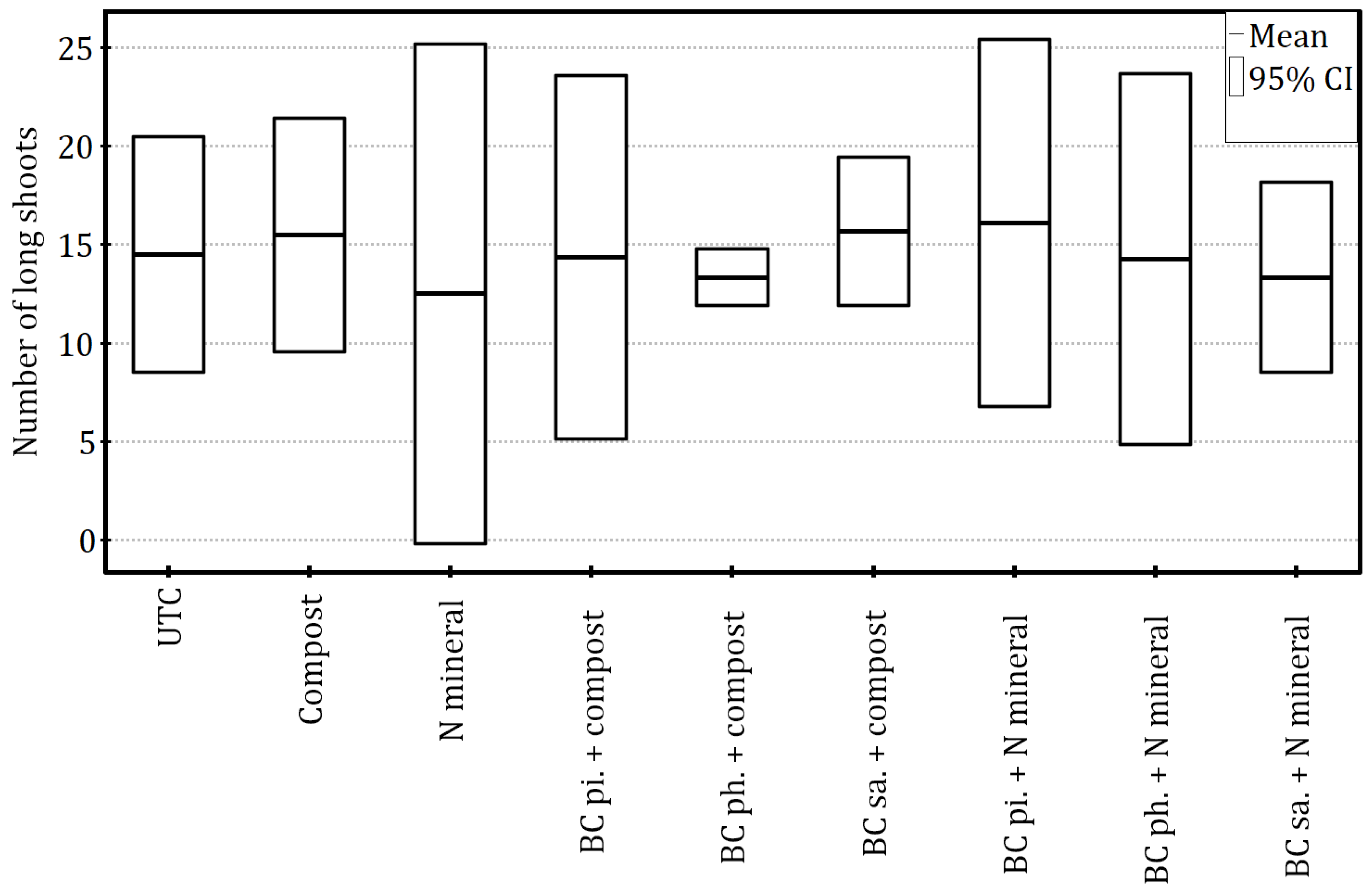

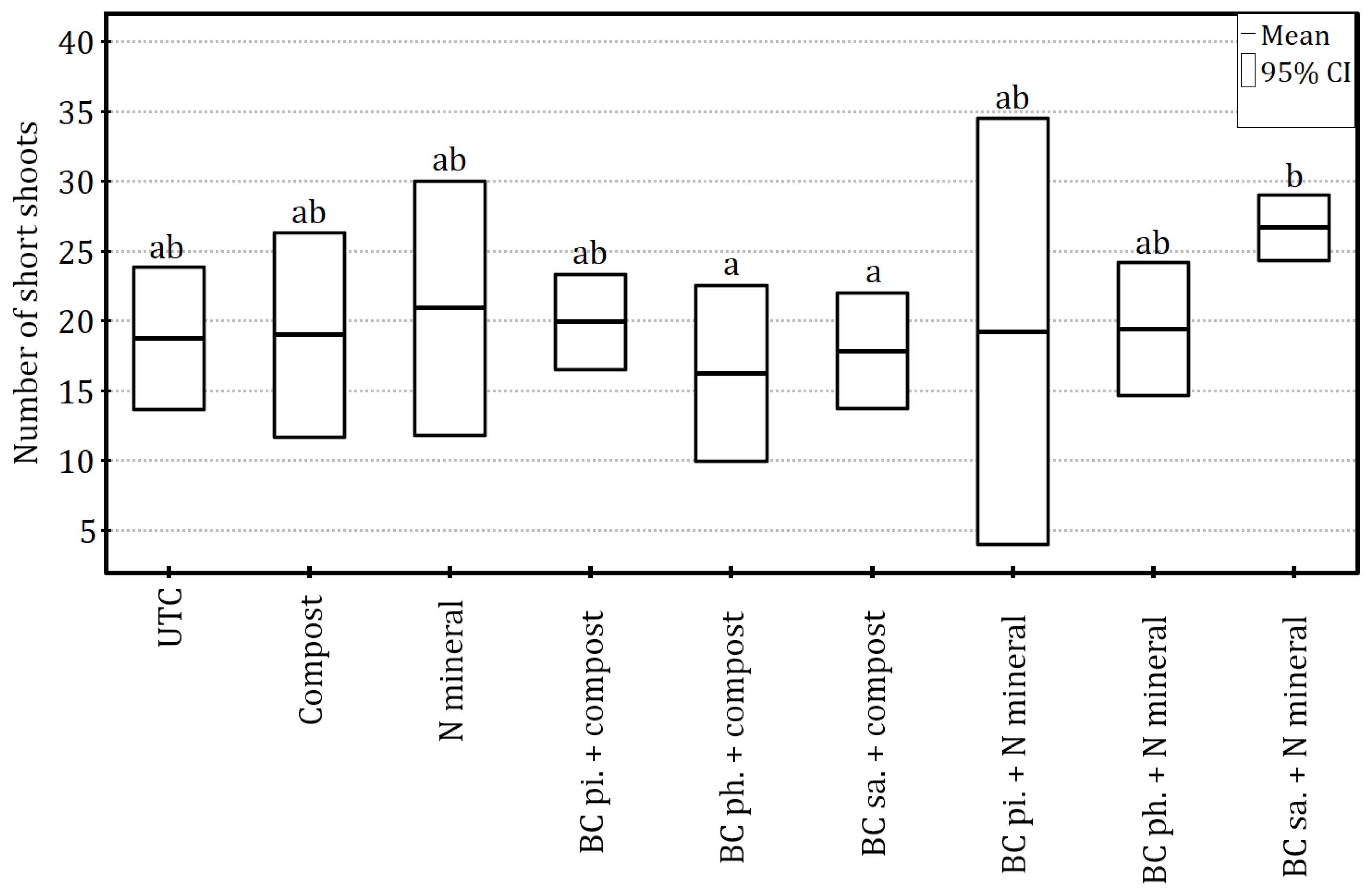

Even though the soil-enriching practices tested did not exert a statistically significant impact on the number of apple tree long shoots (ANOVA:

F8,18 = 0.45,

p = 0.87 and η

2 = 0.17) (

Figure 4), the count of short shoots was significantly affected, with the variability of this parameter having been explained to a large extent (ANOVA:

F8,18 = 2.84,

p < 0.05 and η

2 = 0.56). The surface application of biochar combined with mineral nitrogen fertilisation increased the number of spurs compared to compost application along with soil-surface and planting-hole biochar amendments. In the other treatments, including the control, an intermediate result was obtained (

Figure 5). The multiple linear regression model (

F5,21 = 2.34,

p = 0.08 and R

2 = 0.36) did not allow for a statistically significant assessment of the individual contributions of fertilisation-related factors on the number of short shoots, despite accounting for 36% of the variance in this parameter (

Table 5).

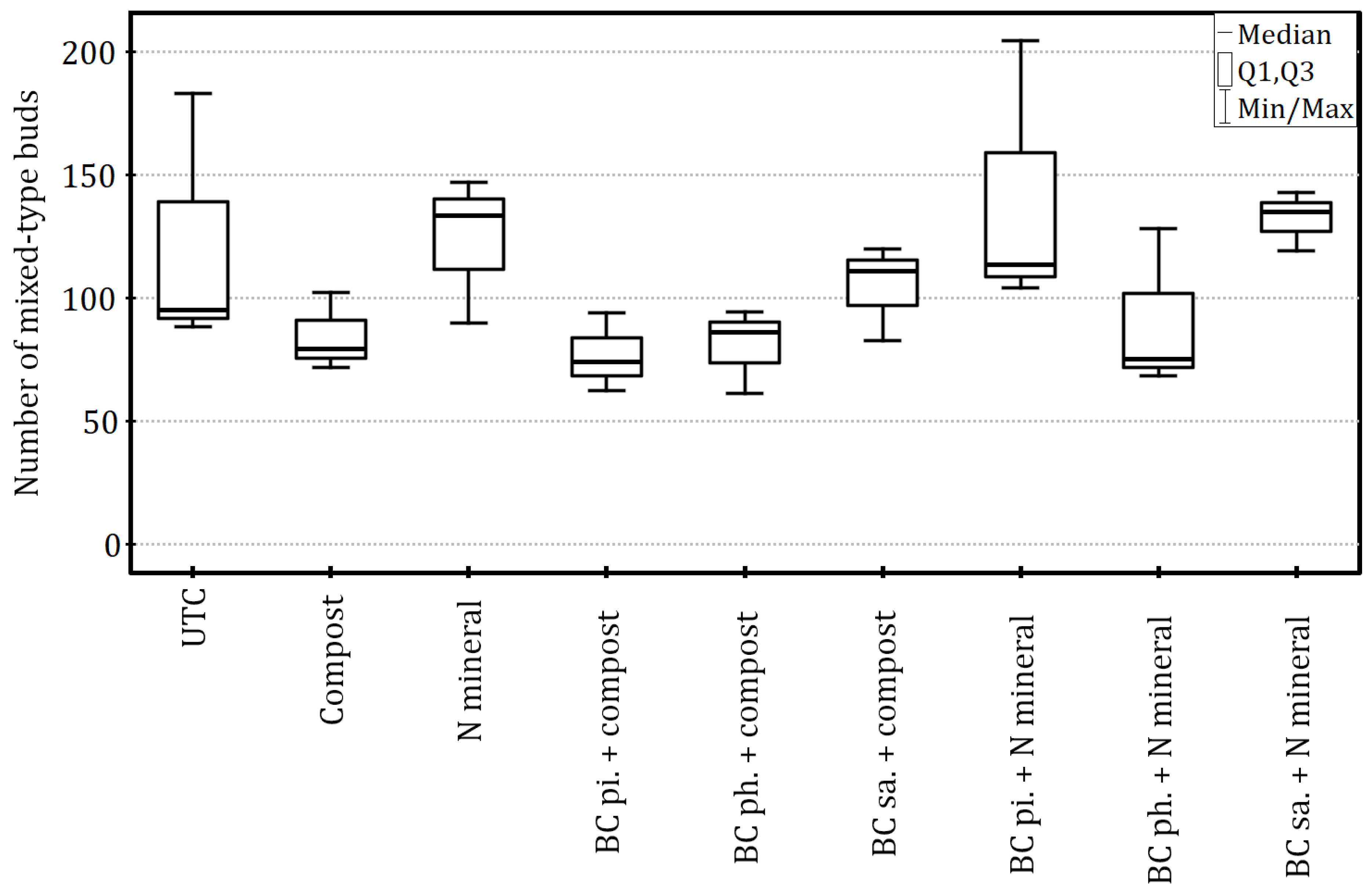

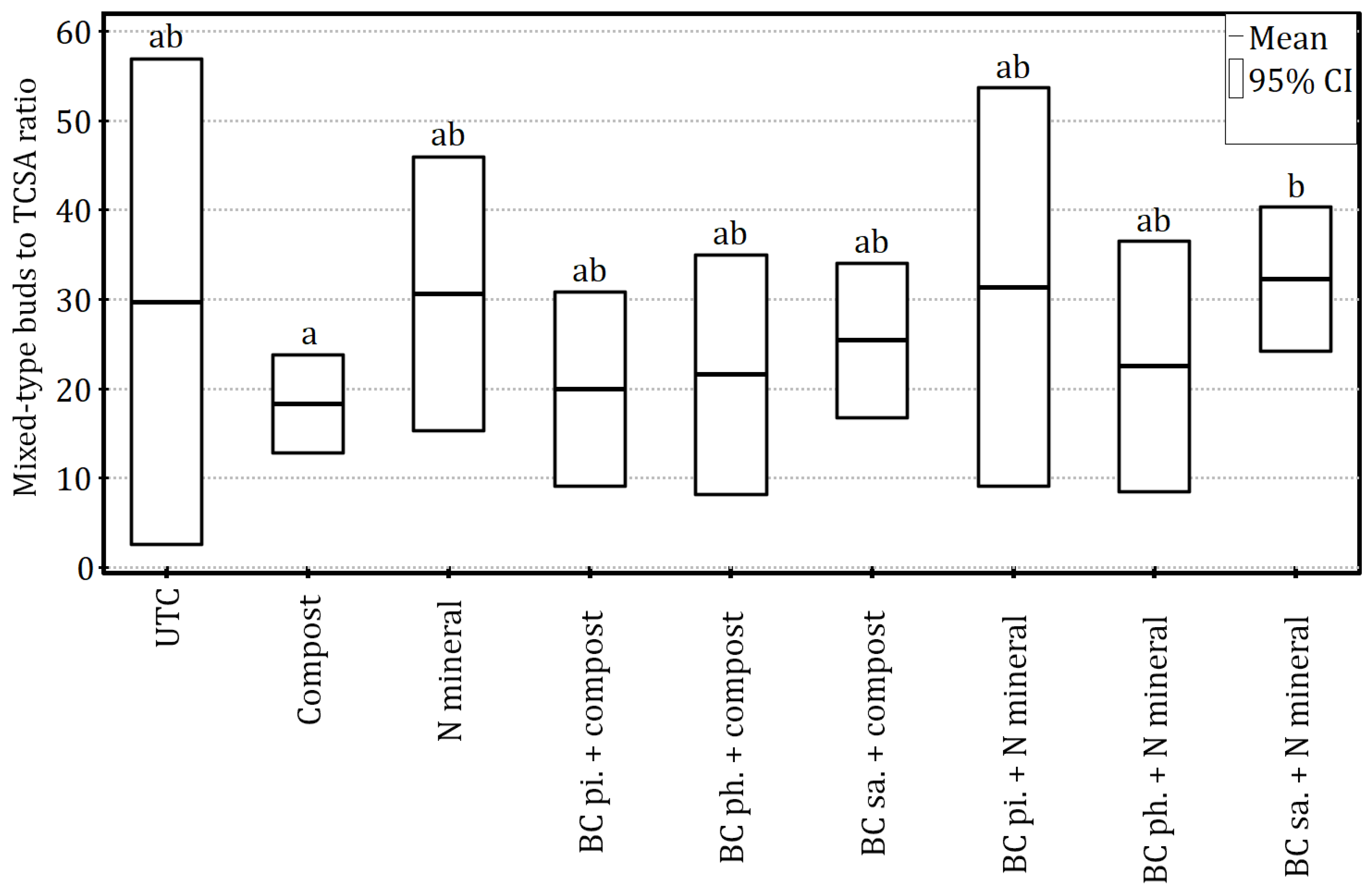

Despite not affecting the number of mixed-type buds (Kruskal–Wallis test:

H8 = 13.52,

p = 0.10 and ε

2 = 0.31) (

Figure 6), the soil amendments had a statistically significant impact on the growth-related fruiting potential of apple trees, which was calculated as a ratio of generative buds to the trunk cross-sectional area (Welch’s ANOVA:

F”

8,7.40 = 3.74,

p < 0.05 and η

2 = 0.50). Consequently, plants fertilised with mineral nitrogen in combination with surface-applied biochar had a significantly higher index value than those fertilised with compost (

Figure 7), which suggests the better use of growth vigour to initiate generative buds. Eventually, partitioning off all fertilisation-related factors in the regression model (

F5,21 = 3.52,

p < 0.05 and R

2 = 0.46) revealed that compost promoted tree vegetative growth at the expense of formation of mixed-type buds for the subsequent year’s yield, with this being reflected in the significantly negative value of coefficient b (

Table 6).

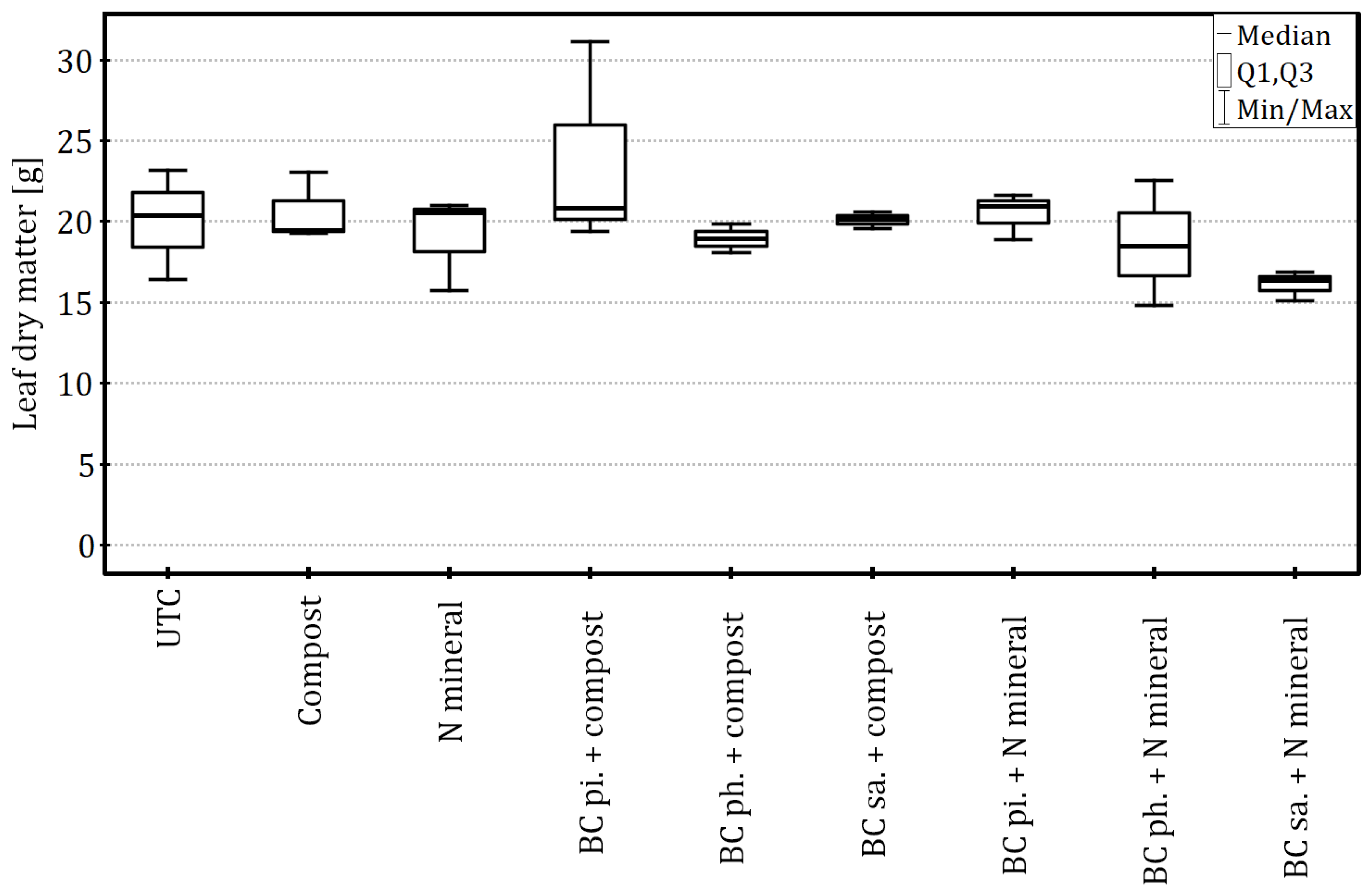

Neither the leaf area (ANOVA:

F8,18 = 1.21,

p = 0.35 and η

2 = 0.35) nor dry matter (Kruskal–Wallis test:

H8 = 8.60,

p = 0.38 and ε

2 = 0.03) depended significantly on the biochar and fertiliser combinations applied (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

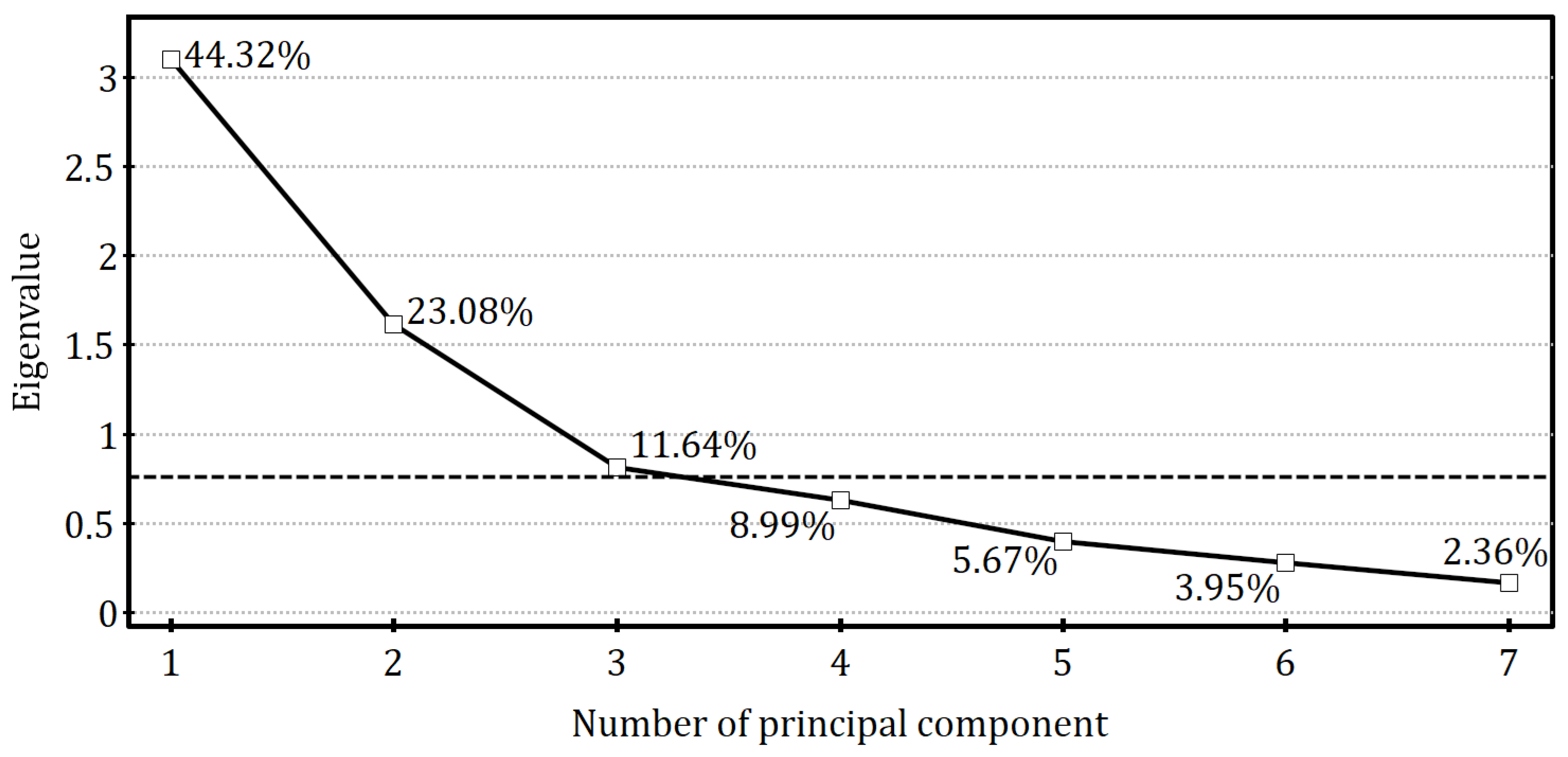

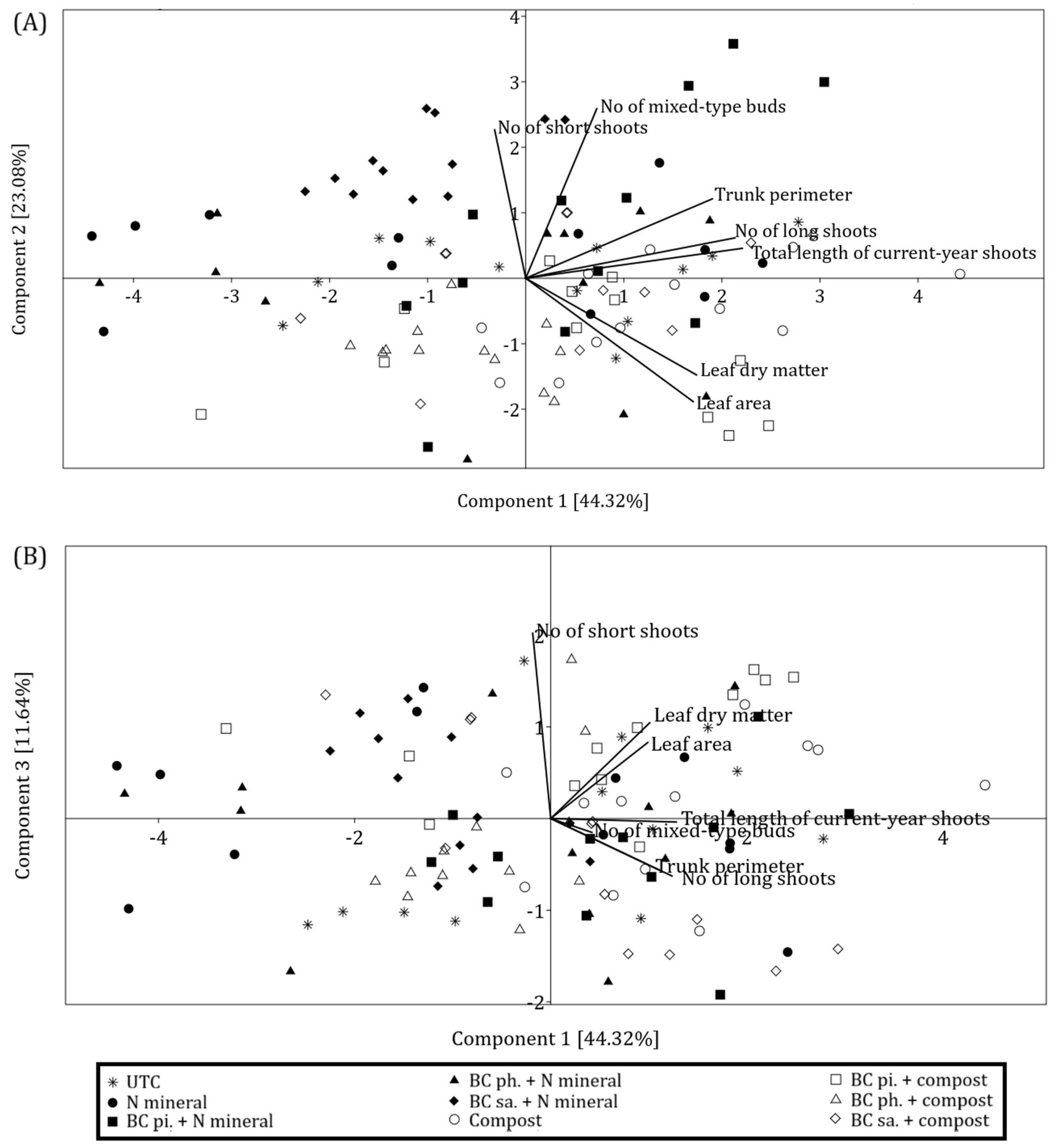

Seven original parameters describing tree growth and fruiting potential were subjected to the principal component analysis. Based on the scree plot, the first three principal components (PC1–PC3), which explain together 79.04% of the variance in the original variables, were retained for further explanatory analyses (

Figure 10).

From the factor loadings for the three selected principal components presented in

Table 7, it can be concluded that PC1 is mainly determined by growth-related parameters (the trunk circumference, total length of shoots and number of long shoots), whilst PC2 and PC3 mainly refer to variables describing the yield potential for the following year (the number of short shoots and mixed-type buds). The leaf dry matter, which is a conventional measure of the nutritional status of trees, and leaf area have a similar contribution to all retained components, although they are greater in PC1 than in PC2 and PC3. Therefore, let us consider PC1 as tree vigour and PC2 and PC3 as fruiting potential.

When the original data was reduced to two dimensions (PC1 vs. PC2), the most noticeable pattern was the clustering of points representing trees fertilised with mineral nitrogen (black symbols) almost exclusively in the first and second quadrants of the coordinate system (

Figure 11A). Their positive PC2 values indicate higher fruiting potential. In contrast, trees fertilised with compost (white symbols) were characterised by negative values of this component. The acute angle between the vectors for the number of short shoots and mixed-type buds in

Figure 11A reflects their strong positive correlation, suggesting that this type of generative development was mainly expressed through the formation of fruiting spurs.

In turn, in

Figure 11B, the vector for the number of buds is nearly perpendicular to the vector for short shoots (negligible correlation) but forms an acute angle with the vector for long shoots. Therefore, this pattern of generative development was mainly related to the formation of mixed-type buds on long shoots. However, in the PC1 vs. PC3 configuration, it is not possible to derive as clear of a distinction between point clusters as in the previous case. Roughly equal distribution of points on both sides of the

Y-axis suggests that flower buds on long shoots were formed regardless of the fertilisation regime.

Nevertheless, in both projections (

Figure 11A,B), any particular pattern that would depend on the methods of biochar application is difficult to discern, whilst the points representing the untreated control are scattered more or less throughout the coordinate system.

4. Discussion

Orchard management differs fundamentally from annual crop production. Nonetheless, most of the studies documenting the role of biochar in stimulating plant growth and yields refer to annual crops [

17,

48,

50], with transferring these findings by analogy to perennial fruit tree systems being problematic.

First of all, the primary way to use biochar in annual crop rotation is to introduce it into the soil during regular tillage operations [

62]. Meanwhile, in perennial fruit crops, deep soil tillage (usually ploughing) is only carried out at the stage of preparing the field for planting an orchard [

63]. This could be a convenient time to apply biochar, but alternative methods are also possible, including planting-hole application and surface spreading.

In the case of plough incorporation, biochar would be mixed into the soil across the entire area using a plough in a similar way to organic or phosphate fertilisers. This would ensure its availability in the root system zone as it expands over subsequent years of tree growth, including after the soil in the inter-rows has been overgrown. The planting-hole application involves lower biochar consumption, but the material would not be able to benefit the roots as they expand. In turn, the surface application could be used particularly in existing orchards where soil tillage options are very limited. To date, these methods of biochar application have been used separately in several studies performed in orchards [

22,

54,

64], but no comparison has been made between them. Nor has sufficient attention been paid to the interaction between biochar and fertilisation, despite strong evidence that biochar requires supplementation with fertilisers to exert its full stimulating effect [

48].

According to the results of this study, the soil-enriching practices affected the early-stage growth performance of apple trees to a relatively small extent, with the effect of biochar having been masked by fertilisation regimes. Consequently, it was not possible to compare the effectiveness of the biochar application methods. In this study, biochar had no significant influence on apple trees’ fruiting potential or leaf dry mass, consistent with the findings of Ventura et al. [

22]; similarly, no effects were observed on leaf area or fruiting potential, aligning with Eyles et al. [

52]. In contrast, while the present study detected no biochar-induced changes in trunk diameter, Khorram et al. [

53] reported increases in trunk diameter and shoot number in young apple trees following biochar application, either alone or combined with compost. However, biochar may take many years to show its impact on tree-based crops [

65]. Long-term research may be necessary to assess its effects. The results from the subsequent years of the present experiment, which include data on the tree growth and fruit yield and quality, are being prepared for separate publication.

Apart from the short experimental period, the low effectiveness of biochar in this study may have been contributed to by the (i.) initial high fertility of the soil (

Table 2), which provided non-limiting growth conditions; this aligns with findings by Street et al. [

66], who reported a positive growth response of apple trees to biochar only when it was mixed with pure sand, whilst no such effect was observed in soils of better quality; (ii.) generally favourable weather conditions (

Table 3), as a result of which biochar did not demonstrate its effectiveness in mitigating drought stress [

20]; (iii.) establishment of the orchard on land with no previous history of fruit production, and consequently no possibility for biochar to demonstrate its replanting disease-mitigating properties [

30,

31,

32]; and (iv.) low nutrient requirements of fruit trees due to the presence of perennial elements (rootstock and trunk) in which mineral components are stored [

67]. Overall, our observations largely corroborate the conclusions drawn by Eyles et al. [

52] and Sorrenti et al. [

68] that biochar is unlikely to provide measurable benefits in orchards where soil fertility, water availability and the absence of specific constraints do not limit tree growth and productivity.

There is a growing awareness that biochar should be advisedly matched to both crop requirements and site-specific soil conditions, particularly soil texture and physico-chemical properties [

69]. In the present study, biochar derived from cattle manure was selected for two main reasons. First, this feedstock represents a widely available agricultural waste in regions with intensive livestock production, such as Poland, and its conversion into biochar offers a promising circular-economy solution for nutrient management and soil improvement. Second, manure-based biochar has been shown to enhance crop growth and yield, even in sandy soils and under drought conditions [

70,

71]. However, this type of biochar, despite its proven agronomic value, may not have been the optimal choice for an already alkaline soil (pH ≈ 8) (

Table 2). With its own high pH of 9.5, the material applied may have contributed to a further rise in soil pH, potentially reaching levels unfavourable for apple tree growth and yield—a risk already highlighted for orchards grown on alkaline soils [

51]. Better results might have been achieved with a lower-pH biochar, such as that produced from coniferous wood chips (pH ≈ 6) [

72].

A particularly interesting finding of this study was the contrasting effect of the fertilisation regime on bud formation observed in the regression and principal component analyses. Compost showed a tendency towards reducing the formation of mixed-type buds on short shoots, with the opposite observation made in the case of mineral nitrogen. This suggests that compost-fertilised trees allocated more resources towards vegetative growth at the expense of generative development. Such an outcome is undesirable in intensive dwarf orchards, where a balance between growth and fruiting is crucial for efficient fruit production [

56]. This observation is consistent with the results of Khorram et al. [

53], who also noticed enhanced vigour in apple trees after compost application, without any benefits to fruit yield. A possible explanation is the prolonged release of nitrogen from the organic compounds present in compost [

73], which extended into the second half of the growing season, stimulating tree growth at a time when they should already be building potential for next year’s yield. However, the role of organic matter in shaping soil fertility in orchards should not be devalued [

74], considering that site preparation for new planting is the most appropriate time to introduce it deep into the soil profile whilst performing tillage operations [

63].

It should be emphasised that the present study did not provide sufficient evidence that the administered mineral nitrogen fertilisation yielded any measurable benefits in terms of tree growth or fruiting potential, as reflected in the series of one-way analyses performed. This result stands in line with the long-term observations made in the Wilanów Experimental Orchard in Poland [

75,

76,

77,

78], according to which, in fertile soils rich in organic matter, the release of plant-available nitrogen forms from the mineralisation of soil organic matter is sufficient to fully cover the requirements of apple trees. The response of the trees to additional mineral fertilisation is negligible or non-existent, with excessive doses of fertiliser posing a risk of environmental pollution. The soil organic matter content at the experimental site was relatively high for Polish conditions, which might explain the results obtained (

Table 2).

As no evidence was found to confirm any beneficial effect of biochar on apple tree growth in the first year after planting, further research should focus on the long-term assessment of its effectiveness in conditions where the orchard is exposed to stress, e.g., drought [

79], replant disease [

30,

31,

32], or managed under limited mineral fertilisation [

80] or other suboptimal soil conditions [

81,

82]. A promising research direction is to investigate biochar’s synergistic effects not only with fertilisers but also with microbial inoculants (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi or plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria) to improve orchard productivity [

64].