Research on Vegetation Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms in Karst Desertified Areas Integrating Remote Sensing and Multi-Source Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area Overview

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Extraction of Karst Rocky Desertification Information

2.4. Dynamic Analysis of Karst Rocky Desertification

2.5. CASA Model Estimates NPP

2.6. Spatiotemporal Trend Analysis of NPP

2.7. Analysis of Primary Driving Factors for NPP

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution Analysis of Karst Rocky Desertification

3.1.1. General Characteristics of Spacetime

3.1.2. Dynamic Degree Analysis

3.1.3. Subsubsection

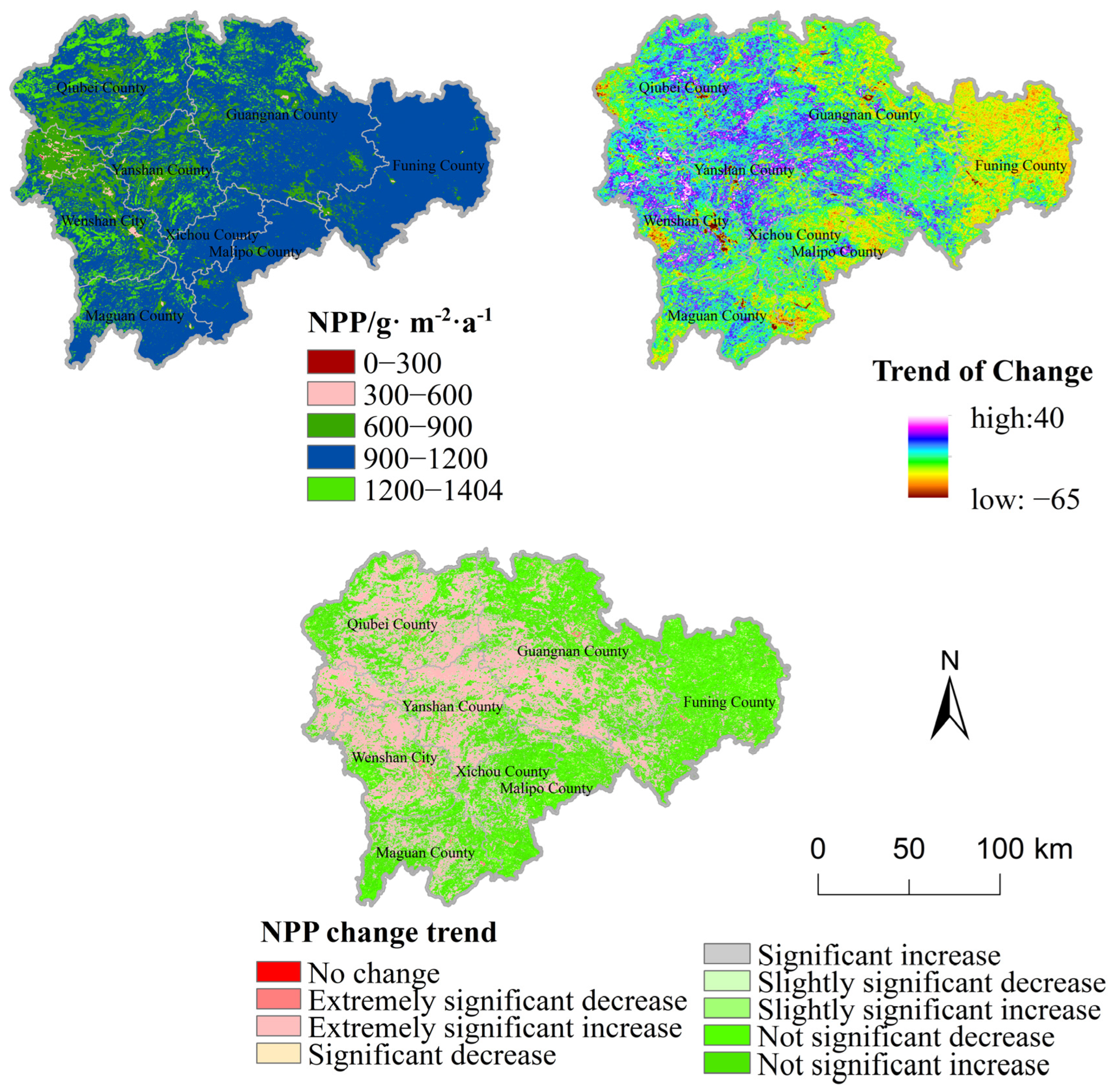

3.2. Analysis of NPP Trend Patterns

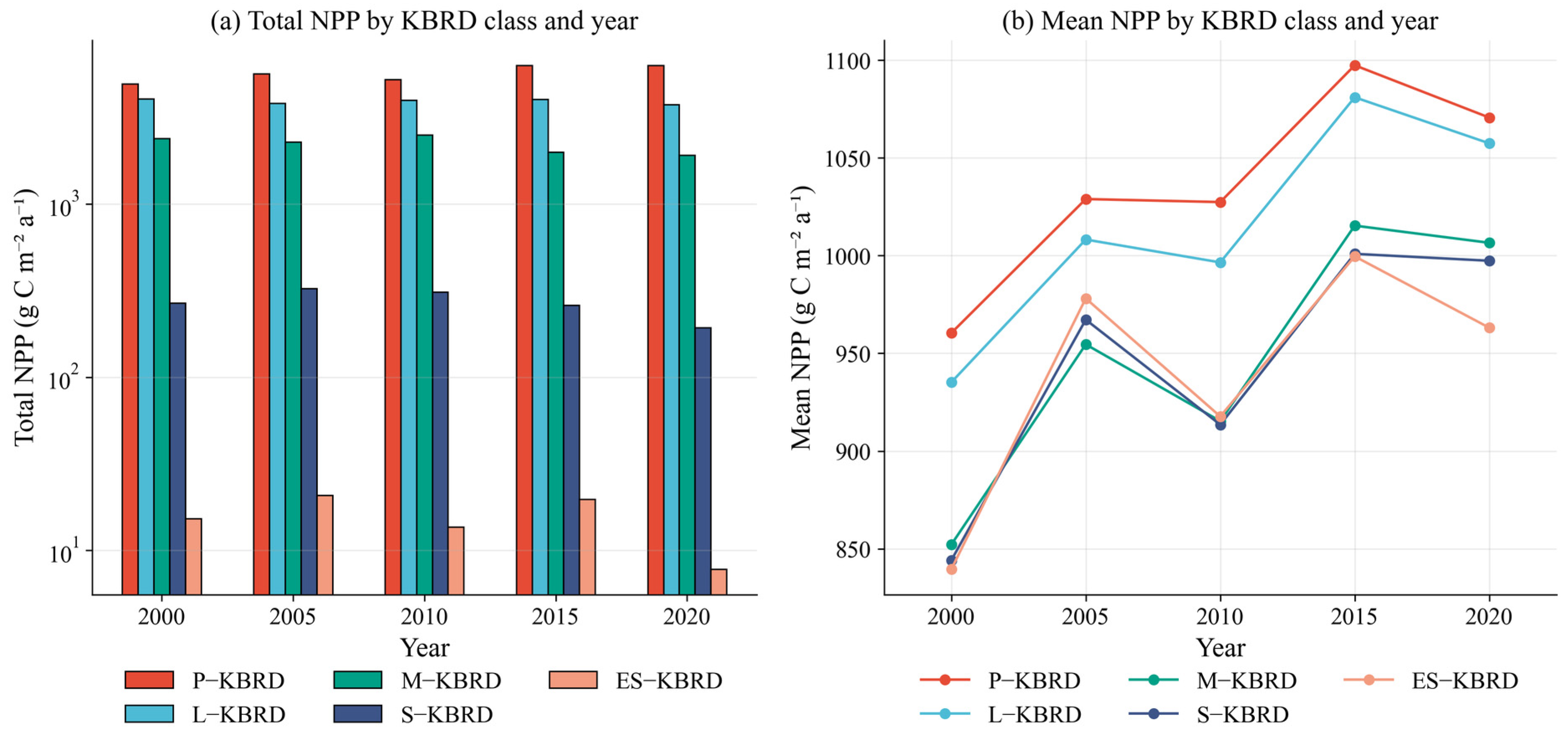

3.3. Coupled Analysis of Karst Rocky Desertification and NPP

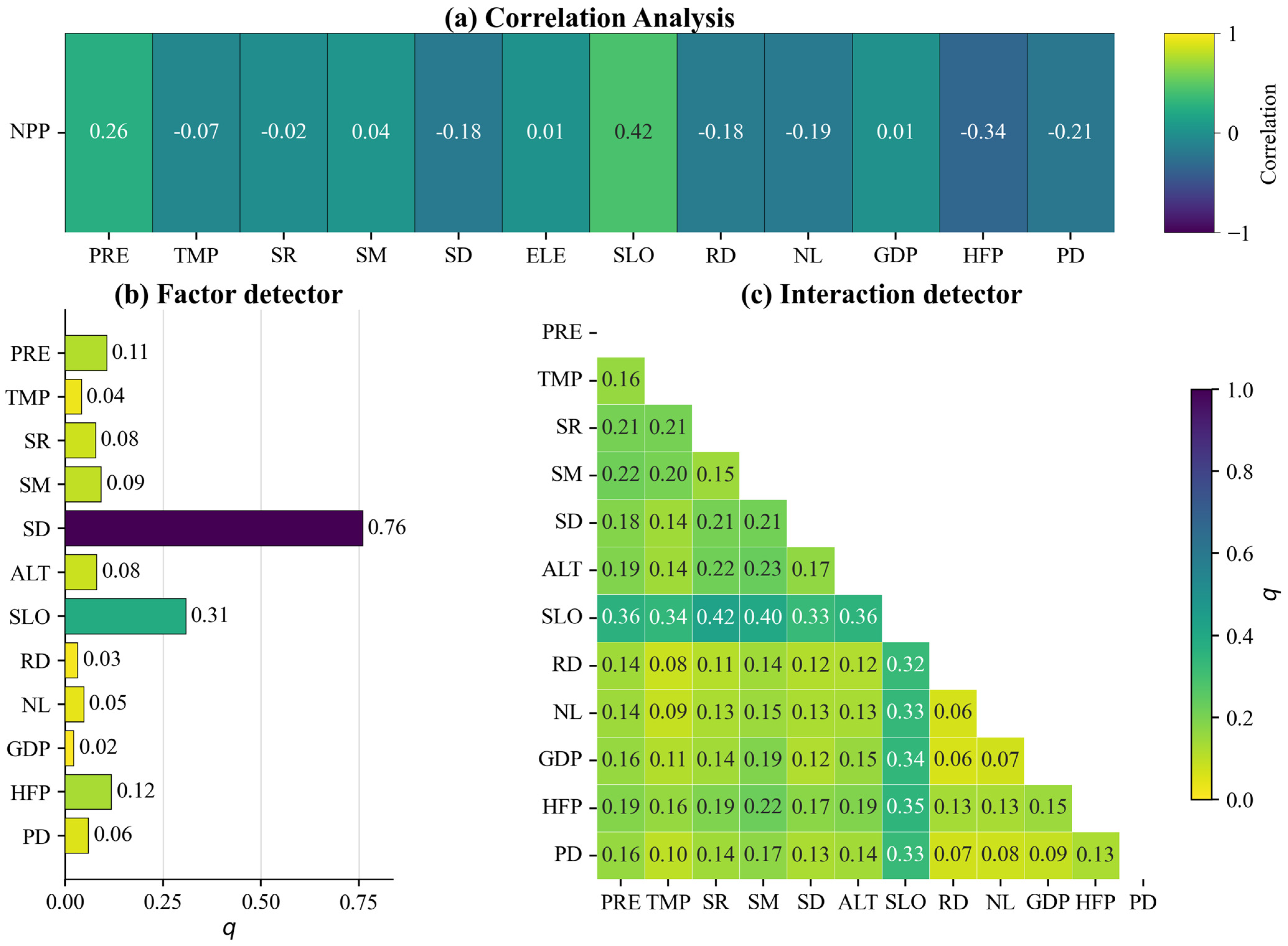

3.4. Analysis of Factors Influencing NPP Driving Forces

4. Discussion

4.1. Classification Analysis of Karst Rocky Desertification

4.2. Trends in Karst Rocky Desertification and NPP

4.3. Main Factors Influencing NPP

4.4. Limits and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuo, T.A.; Zhang, F.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Gao, L.; Yu, S.J. Rocky desertification poverty in Southwest China: Progress, challenges and enlightenment to rural revitalization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1357–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.C.; Bai, X.Y.; Li, Y.B.; Tan, Q.; Zhao, C.W.; Luo, G.J.; Wu, L.H.; Chen, F.; Li, C.J.; Ran, C.; et al. Storage, form, and influencing factors of karst inorganic carbon in a carbonate area in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 67, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Zhao, X.; Dong, P.; Wang, Q.; Yue, Q.F. Extracting information on rocky desertification from satellite images: A comparative study. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.S.; Deng, X.W.; Chen, L.; Xiang, W.H. The soil properties and their effects on plant diversity in different degrees of rocky desertification. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Yang, F.; Fan, Y.W.; Zang, W.Q. The dominant driving factors of rocky desertification and their variations in typical mountainous karst areas of Southwest China in the context of global change. Catena 2023, 220, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentine, P.; Green, J.K.; Guérin, M.; Humphrey, V.; Seneviratne, S.L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S. Coupling between the terrestrial carbon and water cycles—A review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.d.; Yang, J.; Luo, P.P.; Lin, L.G.; Lin, K.L.; Guan, J.M. Assessment of the variation and influencing factors of vegetation NPP and carbon sink capacity under different natural conditions. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Sun, R.; Zhang, H.L.; Xiao, Z.Q.; Zhu, A.R.; Wang, M.J. New global MuSyQ GPP/NPP remote sensing products from 1981 to 2018. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 5596–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.J.; Zhang, X.S.; Chen, M.M. Analysis of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of ecosystem services in mountainous karst areas: A case study of Guizhou Province, China. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2023, 7, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, T.; Oksanen, L.; Vuorinen, K.E.M.; Wolf, C.; Mäkynen, A.; Olofsson, J.; William, J.; Tove, A. The impact of thermal seasonality on terrestrial endotherm food web dynamics: A revision of the exploitation ecosystem hypothesis. Ecography 2020, 43, 1859–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F.; Chen, L.; Meng, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, L.G.; Zhang, X.W. Research on maximum light use efficiency based on CASA-VPM model. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2019, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.L.; Fang, J.Y. Terrestrial net primary production and its spatio-temporal patterns in Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, China during 1982–1999. J. Nat. Resour. 2002, 3, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Liu, H.Y.; Zhang, M.Y.; Gong, H.B.; Cao, L. Nonlinear characteristics of NPP based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition from 1982 to 2015—A case study of six coastal provinces in southeast China. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.Y.; Shi, P.J.; Shao, H.B.; Zhu, W.Q.; Pan, Y.Z. Modelling net primary productivity of terrestrial ecosystems in East Asia based on an improved CASA ecosystem model. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 4851–4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, B.E.; Kafy, A.A.; Samuel, A.A.; Rahaman, Z.A.; Ayowole, O.E.; Shahrier, M.; Duti, B.M.; Rahman, M.T.; Peter, O.T.; Abosede, O.O. Monitoring and predicting the influences of land use/land cover change on cropland characteristics and drought severity using remote sensing techniques. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 18, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Xiong, K.N.; Min, X.Y.; Zhu, D.Y. Vegetation vulnerability in karst desertification areas is related to land–atmosphere feed-back induced by lithology. Catena 2024, 247, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Cardinael, R.; Berre, D.; Boyer, A. A global overview of studies about land management, land–use change, and cli-mate change effects on soil organic carbon. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.S.; Chen, J.H.; Deng, T.; Sun, H. Plant diversity in Yunnan: Current status and future directions. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.H.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.R.; Zhang, C.; Yin, Y.H. Ecological quality evolution and its driving factors in Yunnan karst rocky desertification areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.Y.; Ohsawa, M.; Kira, T. Vertical vegetation zones along 30 N latitude in humid East Asia. Vegetatio 1996, 126, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.F.; Scheffers, B.R. Vertical stratification influences global patterns of biodiversity. Ecography 2019, 42, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Leahy, L.; Ashton, L.A.; Kitching, R.L.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Scheffers, B.R. Ecological patterns and processes in the vertical dimension of terrestrial ecosystems. J. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Xiong, K.N.; Wang, Q.; Tang, J.H.; Lin, L. A review of ecological assets and ecological products supply: Implications for the karst rocky desertification control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.Y.; Qi, J.G.; Yin, R.S. Has China’s natural forest protection program protected forests?—Heilongjiang’s experience. Forests 2016, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delang, C.O. The second phase of the grain for green program: Adapting the largest reforestation program in the world to the new conditions in rural China. Environ. Manag. 2019, 64, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Chen, Z.Z.; Huang, R.J.; You, H.T.; Han, X.W.; Yue, T.; Zhou, G.Q. The effects of spatial resolution and resampling on the classification accuracy of wetland vegetation species and ground objects: A study based on high spatial resolution UAV images. Drones 2023, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.M.; Xiao, L. Sedimentary features and paleogeographic evolution of the middle Permian trough basin in Zunyi, Guizhou, South China. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.J.; Zhou, S.Y.; Yin, X.J. Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics and driving factors of typical karst rocky desertifica-tion area in the upper yangtze river. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldscheider, N.; Chen, Z.; Auler, A.S.; Bakalowicz, M.; Broda, S.; Drew, D.; Hartmann, J.; Jiang, G.H.; Moosdorf, N.; Stevanovic, Z.; et al. Global distribution of carbonate rocks and karst water resources. Hydrogeol. J. 2020, 28, 1661–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Wang, S.J.; Bai, X.Y.; Li, S.J.; Li, H.W.; Cao, Y.X.; Xi, H.P. Evolution characteristics of karst rocky desertification in typ-ical small watershed and the key characterization factor and driving factor. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 6083–6097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Fu, H.; Li, X.M.; Qin, X.C.; Yin, L. Classification of Karst Rocky Desertification Levels in Jinsha County Using a Feature Space Method Based on SDGSAT-1 Multispectral Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.Y.; Huang, X.; Jiang, L.; Jin, C.X. Empirical study on comparative analysis of dynamic degree differences of land use based on the optimization model. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 9847–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.Q.; Huang, J.L.; Pontius, R.G.; Tu, Z.S. Comparison of Intensity Analysis and the land use dynamic degrees to measure land changes outside versus inside the coastal zone of Longhai, China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 89, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Chen, K.L.; E, C.Y.; You, X.N.; He, D.C.; Hu, L.B.; Liu, B.K.; Wang, R.K.; Shi, Y.Y.; Li, C.X.; et al. Improved CASA model based on satellite remote sensing data: Simulating net primary productivity of Qinghai Lake basin alpine grassland. Geo-Sci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2022, 15, 6919–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.P.; Ren, S.L.; Fang, L.; Chen, J.Y.; Wang, G.Q.; Wang, Q. Improved CASA-Based Net Ecosystem Productivity Estimation in China by Incorporating Developmental Factors into Autumn Phenology Model. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.S.; Randerson, J.T.; Field, C.B.; Matson, P.A.; Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Klooster, S.A. Terrestrial ecosystem production: A process model based on global satellite and surface data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1993, 7, 811–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.R. Applied Regression Analysis; McGraw-Hill Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervenkov, H.; Slavov, K. Theil-Sen estimator vs. ordinary least squares–trend analysis for selected ETCCDI climate indices. Comptes Rendus Acad. Bulg. Sci 2019, 72, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, A.C.; Silva, J.L.B.; Moura, G.B.A.; Lopes, P.M.O.; Nascimento, C.R.; Ribeiro, E.P.; Galvíncio, J.D.; Silva, M.V. Dynamics of land cover and land use in Pernambuco (Brazil): Spatio-temporal variability and temporal trends of biophysical parameters. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 25, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erilli, N.A. Use of trimean in theil-Sen regression analysis. Bull. Econ. Theory Anal. 2021, 6, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztaş, C.; Erilli, N.A. Contributions to Theil-Sen regression analysis parameter estimation with weighted median. Alphanumer. J. 2021, 9, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Tan, S.C.; Li, Y.P.; Wu, H.; Wu, R.J. Quantitative analysis of fractional vegetation cover in southern Sichuan urban ag-glomeration using optimal parameter geographic detector model, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Z.; Wang, J.F.; Ge, Y.; Xu, C.D. An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic charac-teristics of explanatory variables for spatial heterogeneity analysis: Cases with different types of spatial data. Gisci. Remote Sens. 2020, 57, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Li, X.H.; Christakos, G.; Liao, Y.L.; Zhang, T.; Gu, X.; Zheng, X.Y. Geographical detectors--based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.R.; Abuduwaili, J.; Liu, W.; Feng, S.; Saparov, G.; Ma, L. Application of geographical detector and geographically weighted regression for assessing landscape ecological risk in the Irtysh River Basin, Central Asia. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.F.; Chang, Y.; Song, D.N.; Kuang, H.H. Spatial distribution and driving factors of karst rocky desertification in south-west china based on GIS and geodetector. Open Geosci. 2024, 16, 20220625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka Kumar, D. Decision tree classifier: A detailed survey. Int. J. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2020, 12, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Zhang, J.; Hu, W.Y. Spatio-temporal Evolution Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Rocky Desertification in Karst Area of Eastern Yunnan. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2022, 4, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B. Analysis on transformation and evolution of rocky desertification in karst mountainous areas of southwest China. Carsologica Sin. 2021, 40, 698–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.S.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhao, W.Z.; Feng, X.Y. Spatiotemporal change and driving factors of net primary productivity in Qilian Mountains from 2000 to 2020. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 23, 9710–9720. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Shi, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.Z. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors of NPP on the Northern Slope of the Qinling Mountains from 2001 to 2020. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2025, 3, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.R.; Wu, X.C.; Tian, Y.H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.C. Soil property plays a vital role in vegetation drought recovery in karst region of Southwest China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2021JG006544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Lann, T.S.; Ao, X.L.; Yang, L.Y.; Lan, H.X.; Peng, J.B. Evolution characteristic of soil water in loess slopes with dif-ferent slope angles. Geoenvi-Ronmental Disasters 2024, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Cai, C.F.; Shi, Z.H.; Xu, Q.X.; Wang, X.Y. Soil thickness effect on hydrological and erosion characteristics under sloping lands: A hydropedological perspective. Geoderma 2011, 167, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.X.; Jing, J.L.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.F.; He, H.C. Assessing the contribution of human activities and climate change to the dynamics of NPP in eco-logically fragile regions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 42, e02393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Wang, K.L.; Yue, Y.M.; Brandt, M.; Liu, B.; Zhang, C.H.; Liao, C.J.; Fensholt, R. Quantifying the effectiveness of ecological restoration pro-jects on long-term vegetation dynamics in the karst regions of Southwest China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 54, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, J.W.; Shangguan, Z.P. Effect of vegetation restoration on soil carbon sequestration: Dynamics and its driving mechanisms. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.W.; Luo, Y.Z.; Shi, C.M.; Yuan, L. Hydrological effects of vegetation restoration in karst areas research: Progress and challenges. Trans. Earth Environ. Sustain. 2023, 1, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, N.; Jin, R.; Liu, S.M.; Sun, X.M.; Wen, X.F.; Wu, D.X.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.W.; Chen, S.P.; et al. Internet of Things to network smart devices for ecosystem monitoring. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rocky Desertification Level | Code | FVC | Rock Exposure Rate | Slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No rocky desertification | N-KBRD | 0.8–1.0 | 0–0.1 | 0–5 |

| Potential rocky desertification | P-KBRD | 0.6–0.8 | 0.1–0.3 | 5–8 |

| Light rocky desertification | L-KBRD | 0.4–0.6 | 0.3–0.5 | 8–10 |

| Moderate rocky desertification | M-KBRD | 0.2–0.4 | 0.5–0.7 | 10–20 |

| Severe rocky desertification | S-KBRD | 0.1–0.2 | 0.7–0.9 | 20–30 |

| Extremely revere rocky desertification | ES-KBRD | 0–0.1 | 0.9–1.0 | 30–90 |

| Interaction Effect | Discrimination Method |

|---|---|

| Synergy | q(X1∩X2) > q(X1) or q(X2) |

| Double synergy | q(X1∩X2) > q(X1) and q(X2) |

| Nonlinear synergy | q(X1∩X2) > q(X1) + q(X2) |

| Antagonism | q(X1∩X2) < q(X1) + q(X2) |

| Single antagonism | q(X1∩X2) < q(X1) or q(X2) |

| Nonlinear antagonism | q(X1∩X2) < q(X1) and q(X2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Yin, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, C. Research on Vegetation Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms in Karst Desertified Areas Integrating Remote Sensing and Multi-Source Data. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232464

Tang J, Liu Y, Wang Y, Ye J, Yin X, Yu Z, Zhang C. Research on Vegetation Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms in Karst Desertified Areas Integrating Remote Sensing and Multi-Source Data. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232464

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Jimin, Yifei Liu, Yan Wang, Jiangxia Ye, Xiaojie Yin, Zhexiu Yu, and Chao Zhang. 2025. "Research on Vegetation Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms in Karst Desertified Areas Integrating Remote Sensing and Multi-Source Data" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232464

APA StyleTang, J., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Ye, J., Yin, X., Yu, Z., & Zhang, C. (2025). Research on Vegetation Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms in Karst Desertified Areas Integrating Remote Sensing and Multi-Source Data. Agriculture, 15(23), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232464