1. Introduction

The transition to a circular economy is one of the major priorities of the European Union, with it being essential for ensuring long-term economic sustainability, environmental conservation, and strengthening social cohesion [

1,

2]. In this context, as a supplier of basic products, the agri-food system plays a central role [

3], taking into consideration the magnitude of the resource flows involved in the agri-food sector along the entire chain, from the primary producer to the final consumer, as well as the impact on the environment and society in general [

4,

5,

6].

Romania, through its agricultural specificity and the high potential for valorization of biological resources, is currently at a strategic point for accelerating the transition to a circular bioeconomy [

7,

8,

9]. Despite the growing attention to circular transitions in the European Union, Romania’s agri-food system presents distinct structural and institutional features that justify its analysis as a separate case, given its fragmented farm structure and limited available circular infrastructure.

Amid the need to monitor the transition to sustainable production and consumption models, circular economy indicators have attracted increasing attention in the last decade in the specialized literature [

10,

11]. A significant contribution to mapping the current circular economy measurement framework was brought by the systematic review carried out by De Pascale et al. (2021), which identified and classified 61 indicators organized on three spatial levels—micro, meso, and macro [

12]. The paper highlighted the fact that, despite the expansion of research, indicator sets are still under development and their application is uneven across countries and sectors [

12]. Although this review systematized a broad range of existing indicators, most of them remain generic and are rarely operationalized for agri-food systems, which limits their applicability to countries such as Romania. Moreover, a key aspect was the focus on composite indicators, necessary to capture the multidimensional nature of circularity, highlighting the importance of methodologies capable of integrating different types of indicators and ensuring comparability between levels and contexts [

12], which justifies the present study’s choice of a multi-criteria approach in assessing the circular performance of the Romanian agri-food system.

In the same line, Martinho (2021) highlighted the lack of clear standardization in defining and calculating indicators, the existence of conflicting metrics, and the underrepresentation of economic and social dimensions in assessing the circular economy [

13]. The author emphasized the importance of covering the entire supply chain, from nano to macro level, and adapting indicators to local particularities, in order to correlate circular practices with sustainable development objectives [

13]. These findings reinforce the need for an integrated and flexible framework, such as multi-criteria analysis, that allows for the simultaneous assessment of economic, social, and environmental performance and facilitates comparisons at the European level [

14,

15,

16].

Generally, the challenges identified over time in the assessment of circular economic dynamics have indicated the need for integrated tools capable of correlating circular performance with sustainable development objectives and ensuring comparability between entities and time periods [

2]. In this sense, the use of an integrated set of indicators, covering economic, social, and environmental dimensions, represents an optimal solution for facilitating the transition to sustainability and a circular economy in the agri-food sector, while also providing a solid framework for strategic decisions and collaboration between actors in the value chain [

17,

18].

Recent studies have increasingly examined the role of social and entrepreneurial innovation in fostering the transition to a circular economy. Gorgon et al. (2024) noted that green business negotiations are one of the key dimensions of sustainable transformation, requiring the integration of environmental criteria in all phases of decision-making within organizations [

19]. Their structure clearly illustrates an understanding of how effective negotiation processes can help to facilitate the change from traditional to green business models [

19]. Complementary findings by Prokopenko et al. (2024) illustrated that it is through green entrepreneurship that sustainability is achieved, through creativity, partnerships and technological innovation, and the generation of social and environmental plus value, including major job creation and CO

2 reductions [

20]. In Romania, recent evidence by Dumitrescu et al. (2024) evaluates the fact that another necessity to circular and inclusive growth is met by social economy actors, the social enterprises and cooperatives [

21].

Multi-criteria analysis provides a methodological framework that enables the integration of diverse indicators and facilitates cross-dimensional assessment within a transparent and replicable structure [

22,

23]. Thus, multi-criteria analysis is an appropriate approach, as it allows for the aggregation of diverse sets of relevant indicators, the simultaneous assessment of economic, social, and environmental dimensions, and the identification of strengths and vulnerabilities in a unified and transparent framework [

24].

Therefore, several gaps were noted in the specialized literature on the circular economy applied to the agri-food sector, which justify the approach of the present study.

First, there is little research that simultaneously integrates the economic, social, and environmental dimensions into a single analytical framework capable of providing a balanced picture of circular performance [

25,

26]. For example, an underrepresentation of the social dimension was observed in circularity indicators [

27,

28,

29,

30], and an approach that measures value added, employment, and emissions simultaneously could provide a complete perspective on circular sustainability [

31].

At the national level, assessments of Romania’s circular economy performance have been undertaken [

32,

33,

34], generally showing the country below the EU average. However, these national-level assessments mostly consider individual indicators in isolation and do not provide an integrated framework that captures trade-offs and synergies across dimensions, which is the contribution of the present paper. This gap is particularly important for Romania, where farm fragmentation, underdeveloped waste management infrastructure, modest absorption of EU funds, and low levels of private investment create unique structural barriers compared to other EU economies.

Taken together, the literature provides valuable conceptual and methodological insights but remains fragmented, with limited attention to the agri-food sector and social resilience. To address these challenges, this study proposes to complement these efforts through a multi-criteria analysis applied to the Romanian agri-food system, using circular economy-specific indicators taken from the Eurostat database and a methodology for calculating a composite score that ensures the comparability of the results.

In this context, the research questions were as follows:

What is the current level of circular economy performance in the Romanian agri-food system compared to the European Union average?

How has Romania’s economic, social, and environmental performance evolved between 2014 and 2022 in the context of the transition to the circular economy?

What are the key areas in which Romania has competitive advantages and in which it exceeds the EU average?

To what extent do the indicators for which “smaller” means “better” contribute to improving Romania’s position in the circularity ranking?

The novelty of this study lies in integrating Eurostat circular indicators into a multi-criteria framework tailored to the agri-food sector, allowing for the identification of Romania-specific barriers and opportunities and the derivation of policy insights also relevant to other emerging EU economies.

The research gap was addressed by providing an assessment of circular economy performance in the Romanian agri-food sector, explicitly combining economic, social, and environmental dimensions into a single composite index. The contribution lies in linking indicator relevance to agri-food chain functions and deriving Romania-specific policy implications.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the methodology, including data sources, indicator selection rules, normalization and weighting procedures, and robustness checks.

Section 3 presents the empirical results for the analysis between 2014 and 2022.

Section 4 discusses the findings in light of structural and institutional drivers and identifies policy implications. The study’s limitations and directions for further research are also described in this section.

Section 5 concludes with key insights and recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

For the multi-criteria analysis for the assessment of the social, economic, and environmental performance of a circular production system, Romania was selected as a case study. For this analysis, data were collected from the Eurostat database on circular economy-specific indicators.

The multi-criteria analysis focuses on the circular performance of the agri-food system in Romania, in the context of the circular bioeconomy. The indicators were selected according to their relevance for the agri-food supply chains: production, distribution, consumption, food waste management, and valorization of biological resources.

The comparison with the EU average allowed Romania’s strengths and weaknesses to be highlighted. The analysis was structured on three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. For each, relevant indicators were selected, and the performance was assessed in relation to the European average. Future development scenarios assume maintenance of the current pace and an acceleration of the circular transition.

2.1. Indicator Selection, Eligibility Criteria, and Directionality of Indicators

The selection of indicators followed an eligibility process to support sectoral applicability. There were three main criteria that guided the process for indicator selection. First, they needed to illustrate direct or indirect connections with agri-food supply chains such as production, processing, distribution, consumption, disposal, and resource recovery. Indicators measuring waste generated in other sectors, with no relation to agri-food, for example, construction, extractive industry, etc., such as mineral waste production, and the recycling of construction materials, were excluded. Second, only indicators with availability and comparable measurement units for both Romania and the EU average were retained. Lastly, preference was determined to be interpretability in the agri-food context, thus the exclusion of indicators with poor sector specificities, like urban waste per capita or bioenergy from forestry residues, which have no contribution specifically associated with food systems. This approach is in line with recent work that combined contextual selection and methodological compatibility in circular economy analyses [

10,

12,

13].

Therefore, in order to assess Romania’s positioning in relation to the European Union average in the field of circular economy, a composite, weighted, and normalized score was developed, as described below.

In order to capture the evolution of Romania’s performance over time in the field of circular economy, the score was calculated for two reference years: 2014 and 2022. The choice of these years allows for the observation of the progress, or regress, recorded over a period of almost a decade, in the context of continuously transforming European policies, the funds available for the green transition, and the evolution of the national economic and social context. The choice of 2014 as a baseline and 2022 as the most recent available year was also motivated by policy cycles: the period broadly overlaps with the first EU Circular Economy Action Plan (2015–2020), followed by its reinforcement in the 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan, allowing us to capture the structural changes associated with these two major strategic frameworks [

35,

36].

Through this comparative approach, it is possible to more clearly identify the areas in which Romania has made significant progress, but also those segments in which the gap with the EU average has widened. maintained or even intensified.

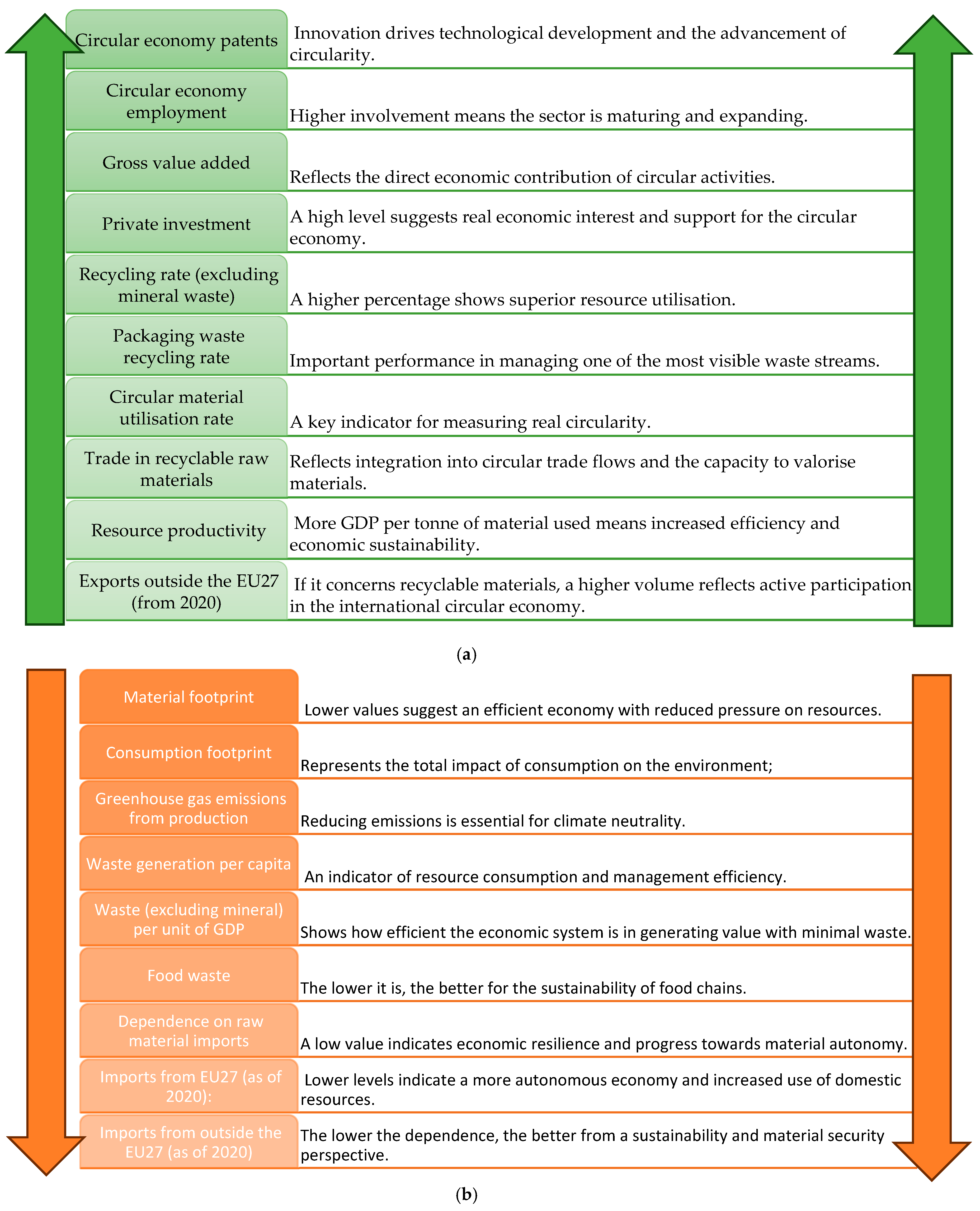

Circular economy indicators were grouped into two categories. First, for those where ‘higher’ means ‘better’, values above the EU average indicate progress and superior performance (

Figure 1a,b).

In these cases, a value lower than the EU average is a sign of increased efficiency, sustainability, or autonomy.

Starting from the Eurostat database, circular economy indicators with direct relevance to agri-food chains and the objectives of the analysis were selected (

Table 1).

For each indicator, a relative performance score was constructed, relating Romania’s value to the EU average and standardizing the meaning of the interpretation. First, the direction of the indicator (Higher = better = true in

Table 1) was coded.

Some of the indicators chosen (for example, patents linked with the circular economy, private investment in circular economy activities) come from the Eurostat monitoring framework and are reported at the macro level. These were included as proxies for innovation and financial investments, with the understanding that they do not only reflect agri-food systems engagement but also reflect the overall economic dimension.

In the discussion section, several indicators, while not directly measuring behavioral aspects, were considered as proxies for behavioral change in the agri-food system. For instance, food waste, packaging waste recycling rates, and waste generation per capita reflect consumer practices and awareness, while the consumption footprint captures broader lifestyle patterns. These proxies allow the model to indirectly incorporate behavioral dimensions, despite the absence of primary survey data.

2.2. Normalization and Aggregation Procedure

To ensure comparability across indicators with different units of measurement, all variables were normalized on a common scale from 0 to 5.

Let denote the value of indicator i for Romania, and the corresponding European Union average.

For each indicator, the circularity index score

was calculated as follows:

The minimum function prevented extreme ratios from exceeding the upper bound, while values below 0 were to be truncated to 0.

Therefore, for indicators with a positive orientation, the score starts from the Romania/EU average ratio. For those with a negative orientation, where lower values are desirable (i.e., false in

Table 1), the inverse EU average/Romania ratio was used. In this way, a score of 1 indicates parity with the EU average, values > 1 signal superior performance, and values < 1 indicate inferior performance, regardless of the native meaning of the indicator.

In the literature on multi-criteria analysis of circular economy performance, there is no clear consensus on the optimal way to establish weights for indicators. Some studies use AHP, Entropy, or expert-based assessments to differentiate the relative importance of criteria, but these approaches can introduce a high degree of subjectivity and can lead to results that are sensitive to the national context or the profile of respondents [

37,

38,

39].

After analyzing the evolution of scores for each indicator during the period 2014–2022, the next logical step is the aggregate assessment of Romania’s performance within the three fundamental dimensions of sustainability: economic, environmental, and social. To this end, a standardized multi-criteria methodology was applied, based on normalized scores and balanced weights.

To coherently assess Romania’s circular performance in the agri-food sector, a structured multi-criteria approach was adopted, which groups the analyzed indicators according to the three fundamental dimensions of sustainability: economic (coupled with innovation), environmental, and societal. For the social dimension, proxy indicators of socio-economic resilience were used, such as waste intensity, import dependence, and trade in recyclable materials, as determinants of price stability, budget pressure, and employment potential in the circular economy. This classification allows for a thematic interpretation of the results and an integrated assessment of the overall performance. In total, 18 indicators were logically distributed between the three dimensions, depending on their nature and main relevance (

Table 2).

The economic dimension included indicators such as resource productivity, private investment in the circular economy, value added, employment in circular sectors, and the number of patents. These reflect the economic and innovative capacity of the agri-food system.

The environmental dimension included indicators expressing the pressure on ecosystems and the degree of material circularity: material footprint, food waste, waste generation, greenhouse gas emissions, the rate of use of circular materials, as well as recycling and consumption performance.

The social dimension included indicators on waste intensity relative to GDP, dependence on imported materials, and participation in trade in recyclable materials—all of which are relevant for resilience and socio-economic stability.

To ensure methodological balance, each dimension was assigned an equal weight of 33.3%. After calculating the normalized scores (0–5) for each indicator, the arithmetic mean for each dimension was determined.

Therefore, for each sustainability dimension, the mean score was then calculated as:

where

is the number of indicators included in dimension

d.

Finally, the three averages were used to calculate the composite circular performance index (

CPI), through a simple arithmetic mean.

where,

aEDim is average economic dimension score

aEnvDim is average environment dimension score

aSDim is average social dimension score.

This balanced approach allowed for a comparative analysis not only at the level of individual indicators, but also at the aggregate level for each essential dimension of sustainability. By comparing the average scores obtained in 2014 and 2022, the direction of Romania’s circular evolution in economic, environmental, and social terms can be observed.

In the case of the present study, the main objective was the comparability of the results between the economic, social, and environmental dimensions, as well as ensuring the transparency and replicability of the calculations. For this reason, equal weights were applied (33.3% for each dimension), thus avoiding external influences on the ranking of indicators and allowing a direct interpretation of the scores in relation to the European Union average.

This approach follows the principles of Weighted Linear Combination within a Multi-Criteria Analysis (MCA) framework, as established in Saaty (1980) [

40] and further operationalized by Viccaro et al. (2022) [

41].

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To test robustness, two alternative weighting schemes were also considered as follows: (i) economic dimension weighted at 50%, and (ii) social dimension weighted at 50%

2.4. Limitations

Although the methodological design ensures transparency and comparability, several limitations should be acknowledged. The analysis relies exclusively on secondary Eurostat data, which may not fully reflect sector-specific or behavioral dimensions of circularity. In addition, while equal weighting across the economic, social, and environmental pillars enhances neutrality, it may simplify the relative importance of each dimension. Future studies could incorporate expert-based weighting methods such as the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) [

40] or Entropy weighting to capture stakeholder preferences and test methodological robustness.

3. Results

The analysis highlights a circular performance landscape characterized by significant differences between areas, but also by performance cores that can be leveraged as support points for future developments.

In 2014, Romania was in an early stage of the transition to a circular economy, characterized by an uneven profile, with significant extremes between different indicators. The scores obtained show a combination of strengths, especially in terms of reduced import dependence and certain trade aspects, and multiple weaknesses, especially in the area of economic value generated, efficiency, and private involvement.

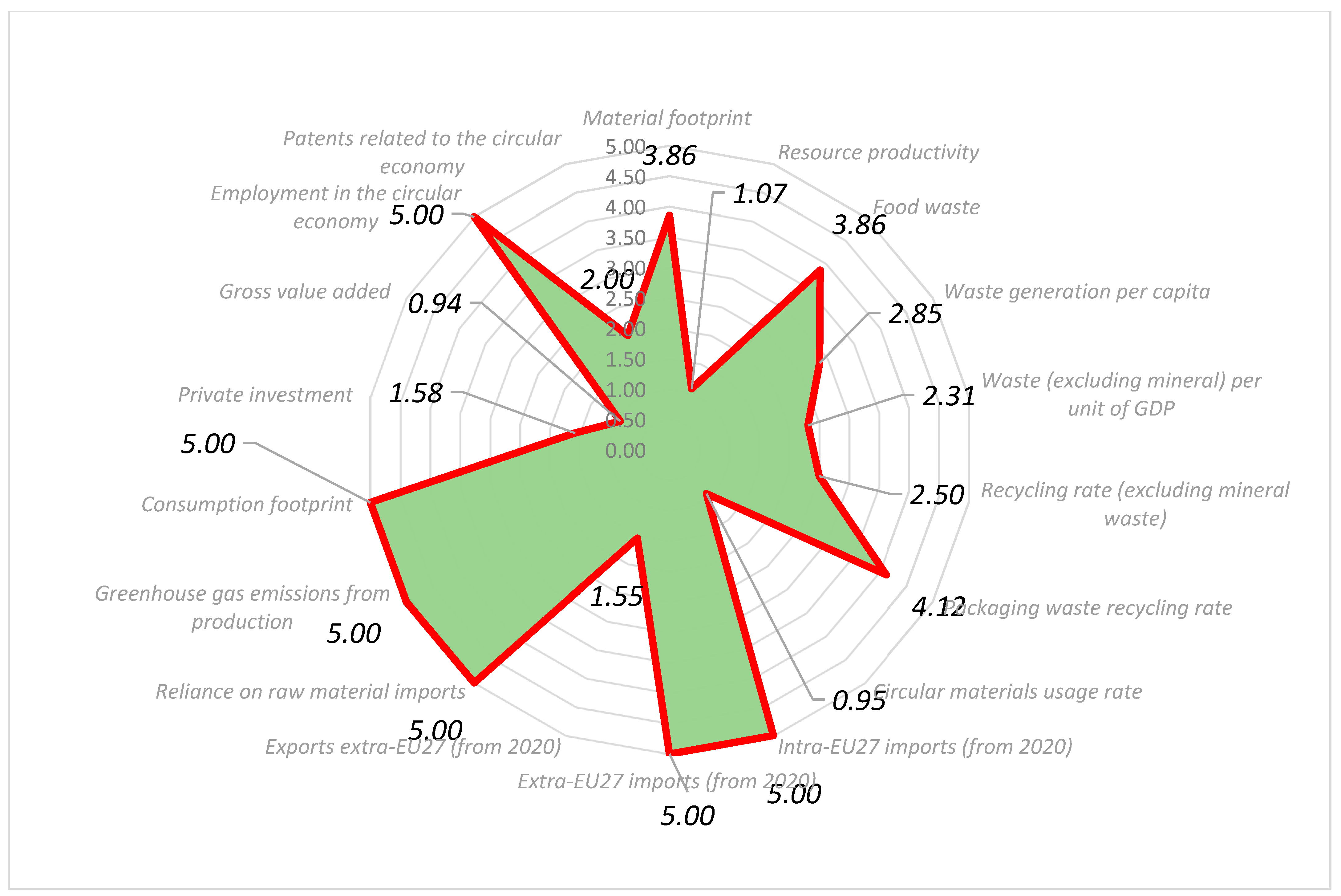

Romania recorded maximum scores (5.00) on several key indicators (

Figure 2). A notable example is the dependence on raw material imports, where the significantly better positioning compared to the European average indicates a relatively lower reliance on external resources. Similarly, Romania shows lower greenhouse gas emissions from manufacturing than the EU average, reflecting the country’s current production structure and energy intensity profile.

Other top scores were recorded for employment in the circular economy and for the consumption footprint, indicating relatively lower resource pressure compared to the EU average. However, this pattern may also reflect differences in consumption intensity and structural characteristics of domestic demand. In the area of trade in recyclable raw materials, Romania achieved top scores for both intra- and extra-EU imports.

These trends may reflect structural changes, but further research is required to identify specific drivers.

Another relatively favorable point was the recycling rate of packaging waste, with a score of 4.12, which could indicate the existence of functional selective collection systems, at least in certain segments or regions.

Also, the waste generation per inhabitant, with a score of 2.85, indicates a relatively low generation level compared to the EU average. Although not a top result, it can be considered a favorable starting point, with potential for improvement through prevention and consumption efficiency measures.

On the other hand, there were areas of low performance and vulnerabilities. The analysis of the 2014 scores highlights a series of important structural weaknesses. The gross value added generated by activities related to the circular economy had a very low score (0.94), which indicates a modest economic impact of this sector. In the same direction, private investment was also at a very low level (1.58), highlighting the lack of business involvement.

The rate of use of circular materials was also extremely low (0.95), suggesting a largely linear economy, dependent on virgin raw materials and with a low degree of reintegration of materials into the economic circuit. In addition, exports of recyclable raw materials outside the EU recorded a score of only 1.55.

In terms of resource productivity, Romania had a score of only 1.07, reflecting an inefficient use of raw materials for GDP generation. This aspect, correlated with the modest score on waste per unit of GDP (2.31), indicates an economic system in which relatively much waste is still generated in relation to the economic value created.

The year 2014 provides a clear picture of an economy at the beginning of its transition to circularity. There were a few areas of notable performance, especially in terms of trade in recyclables, emissions, and consumption, but most indicators showed major structural weaknesses.

Overall, Romania recorded an uneven performance, with specific areas of efficiency but without a coherent and integrated approach to the principles of the circular economy.

Analysis of recent results suggests that, although Romania’s circularity profile remains uneven, some areas have registered significant progress, providing clear indications of the directions in which the transition can be accelerated.

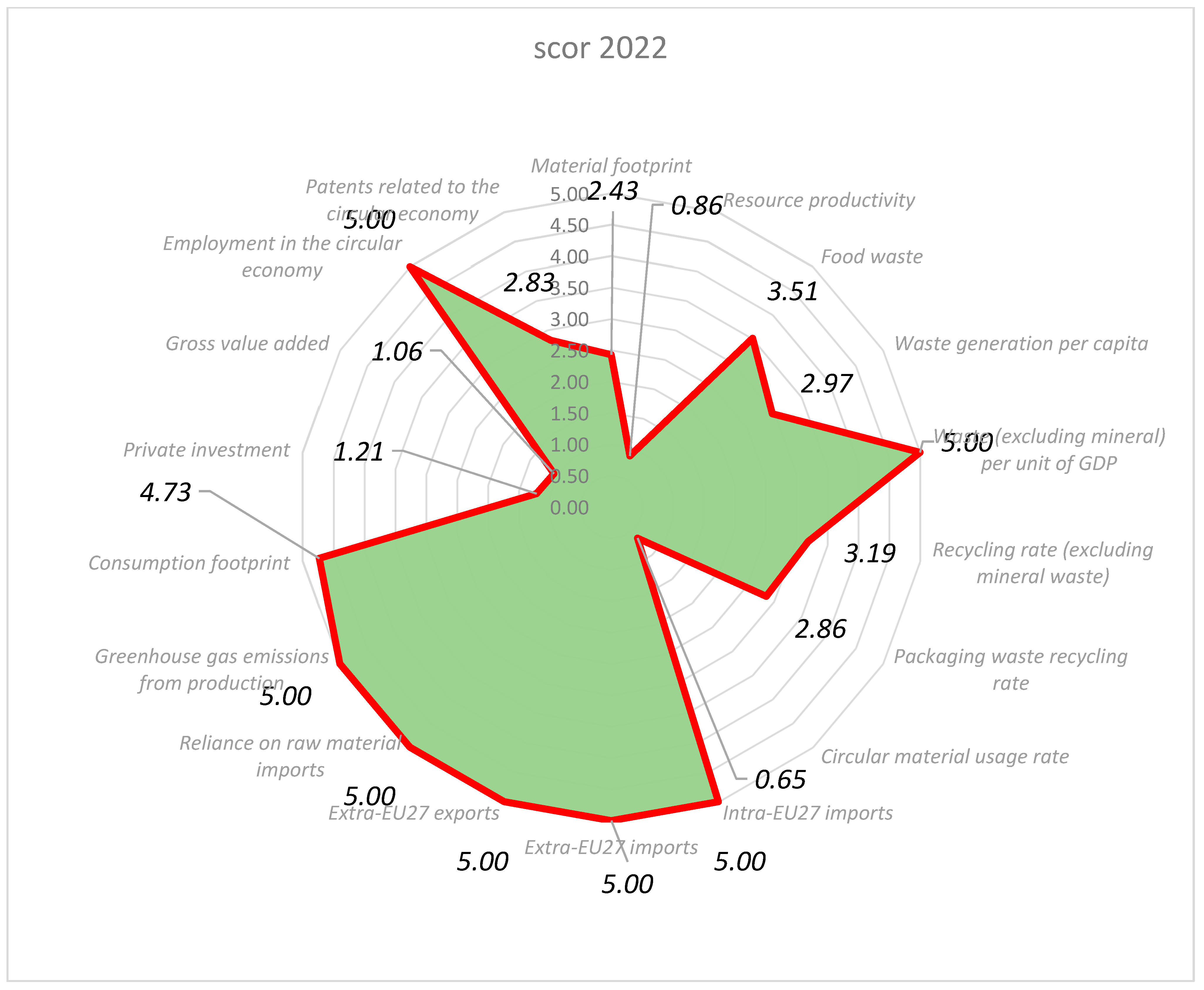

For the year 2022, the Graph has an unbalanced shape, with very high peaks and steep drops, a sign that Romania’s performance is fragmented, with excellence in a few areas and structural weaknesses in others. Such scores can be useful for prioritizing public policy interventions, investments and regulations, especially where scores are below 2. (

Figure 3)

The resulting radar chart highlights Romania’s uneven performance in the transition to a circular economy. It is noteworthy that several indicators where Romania reaches the maximum score (5), suggesting a significantly better positioning than the European average. These include dependence on raw material imports, greenhouse gas emissions from production, waste per unit of GDP (excluding minerals) and patents related to the circular economy.

At the opposite end, there are areas where Romania registers extremely low values, signaling critical deficiencies in the circular economy. Thus, gross value added generated, private investment, circular materials utilization rate, circular employment and resource productivity are all areas with scores ranging between 0.65 and 1.21. These figures highlight the lack of investment, low private sector involvement and low economic integration of circularity principles in value chains.

In the middle zone, indicators such as the consumption footprint (4.73), trade in recyclable raw materials (4.04), food waste (3.51), or the packaging waste recycling rate (2.86) are located. These results suggest a partial or uneven performance, in which Romania approaches the EU average, but without consistently exceeding it. These indicators can be considered points of future progress, but also warnings that maintaining these positions requires consolidation policies.

The overall picture is unbalanced. Romania stands out through isolated performances in certain sectors, but suffers from systemic shortcomings in others. This asymmetry indicates that the transition to the circular economy is still in an incipient stage, with areas of high untapped potential.

Therefore, the year 2022 marks a stage of strong contrasts in the evolution of the circular economy in Romania. Compared to 2014, notable progress can be observed in several key areas, stagnation in traditionally weak areas, but also surprising setbacks in sectors where performance was previously solid. This picture highlights the fragmented nature of the transition towards circularity and the lack of balanced development across all components.

Romania continues to register maximum scores (5.00) in several key areas. Thus, dependence on raw material imports remains at a very good level, further suggesting relative autonomy in supply or reduced consumption of primary resources. Likewise, greenhouse gas emissions from production remain at a very low level compared to the EU average, which may reflect either technological efficiency or an economic structure based on less polluting industries, but further research should be performed here.

Employment in the circular economy maintains its maximum score, suggesting a constant involvement of human resources in sectors related to recycling, repair, reuse, or other circular activities.

A spectacular jump was recorded in waste (excluding mineral waste) reported per unit of GDP, where the score increased from 2.31 to 5.00. This progress signals increased efficiency in creating economic value with less waste, which represents one of the essences of the circular economy.

Also, exports of recyclable raw materials outside the EU have seen a dramatic improvement, from a modest score of 1.55 in 2014 to the maximum score of 5.00 in 2022, reflecting Romania’s increased capacity to capitalize on recyclable materials in international trade flows.

The recycling rate (excluding mineral waste) also increased, from 2.50 to 3.19, indicating a trend towards strengthening collection and recycling systems.

However, not all trends are positive. Some areas show stagnation or decline that deserve attention. The material footprint decreased from 3.86 to 2.43, which is a good thing (being an indicator where “lower” means “better”), but the level remains modest compared to long-term targets. Waste generation per inhabitant remained relatively constant (2.85 in 2014 to 2.97 in 2022), indicating a lack of substantial progress in reducing individual waste, even if the performance is decent compared to the EU average. Regarding the food waste, this indicator’s value has declined slightly (from 3.86 to 3.51). The same decreasing trend was observed for the consumption footprint, which has deteriorated slightly (from 5.00 to 4.73).

In addition to these strengths, the analysis also revealed areas where circular performance remained well below potential, indicating structural obstacles that need to be overcome in order to support a balanced transition. The biggest challenges remain in the economic and investment area, where Romania continues to register very poor scores:

Private investment fell from 1.58 to 1.21, signaling low interest of the private sector in circular initiatives, while resource productivity recorded a decline (from 1.07 to 0.86), indicating an even lower efficiency in generating GDP from the resources consumed. Another indicator that decreased was the rate of use of circular materials, which fell from 0.95 to 0.65, confirming the maintenance of a largely linear economy. At the same time, the gross value added of circular activities, although with a slight increase, remained very low (from 0.94 to 1.06). The recycling rate of packaging waste experienced a significant decrease (from 4.12 to 2.86), which is worrying and may indicate dysfunctions in the collection systems or a lack of consumer involvement, but this is an area of further research.

To sum up, the analysis of indicators for 2022 showed a Romania in which the transition to the circular economy is progressing fragmentarily and unevenly.

In the Production and Consumption category, Romania recorded a mixed evolution. The reduction of the material footprint is a positive sign, indicating less pressure on natural resources. Food waste also saw a slight improvement, signaling the beginning of awareness about food losses. The most notable progress was in waste per unit of GDP, where Romania managed to increase economic efficiency by reducing waste per value created. In contrast, resource productivity decreased, reflecting a less efficient economy, and waste generation per capita remained practically constant, suggesting stagnation in terms of waste prevention at the individual level (

Table 3).

In the Waste Management category, Romania recorded a moderate improvement in the overall recycling rate, but lost significant ground in terms of packaging recycling, where the score dropped substantially. This decrease may indicate dysfunctions in the collection system, lower citizen participation, or a lack of incentives for packaging recycling. The situation signals the need for targeted intervention to regain performance in this essential sector.

Regarding the use and trade of recyclable materials, Romania has made significant progress. Exports of recyclable materials outside the EU have increased dramatically, indicating a greater capacity for international valorization. Imports (from the EU and outside the EU) have remained at an optimal level, suggesting stability in trade integration. However, the rate of internal use of circular materials has decreased, confirming that the Romanian economy remains largely linear. In other words, Romania exports more recycled material, but does not sufficiently reintegrate it into its own economy.

In the Global Sustainability and Resilience category, Romania maintained its best results. Dependence on raw material imports and greenhouse gas emissions from production remained at very good levels, indicating autonomy and a lower climate impact. The consumption footprint also remains favorable, although it has deteriorated slightly. Overall, this category indicates a relatively stable, sustainable profile of the economy, compared to the European average.

Competitiveness and innovation remain the most vulnerable category. Private investment has decreased, reflecting a lack of interest or persistent obstacles in mobilizing capital for circular projects. Gross value added has grown only marginally, remaining at a very low level, and the circular economy still contributes marginally to GDP. In contrast, there is clear progress in innovation, reflected in the increase in the number of patents, and a steady involvement of the workforce in circular activities, which can create a solid basis for future developments, if supported by coherent policies.

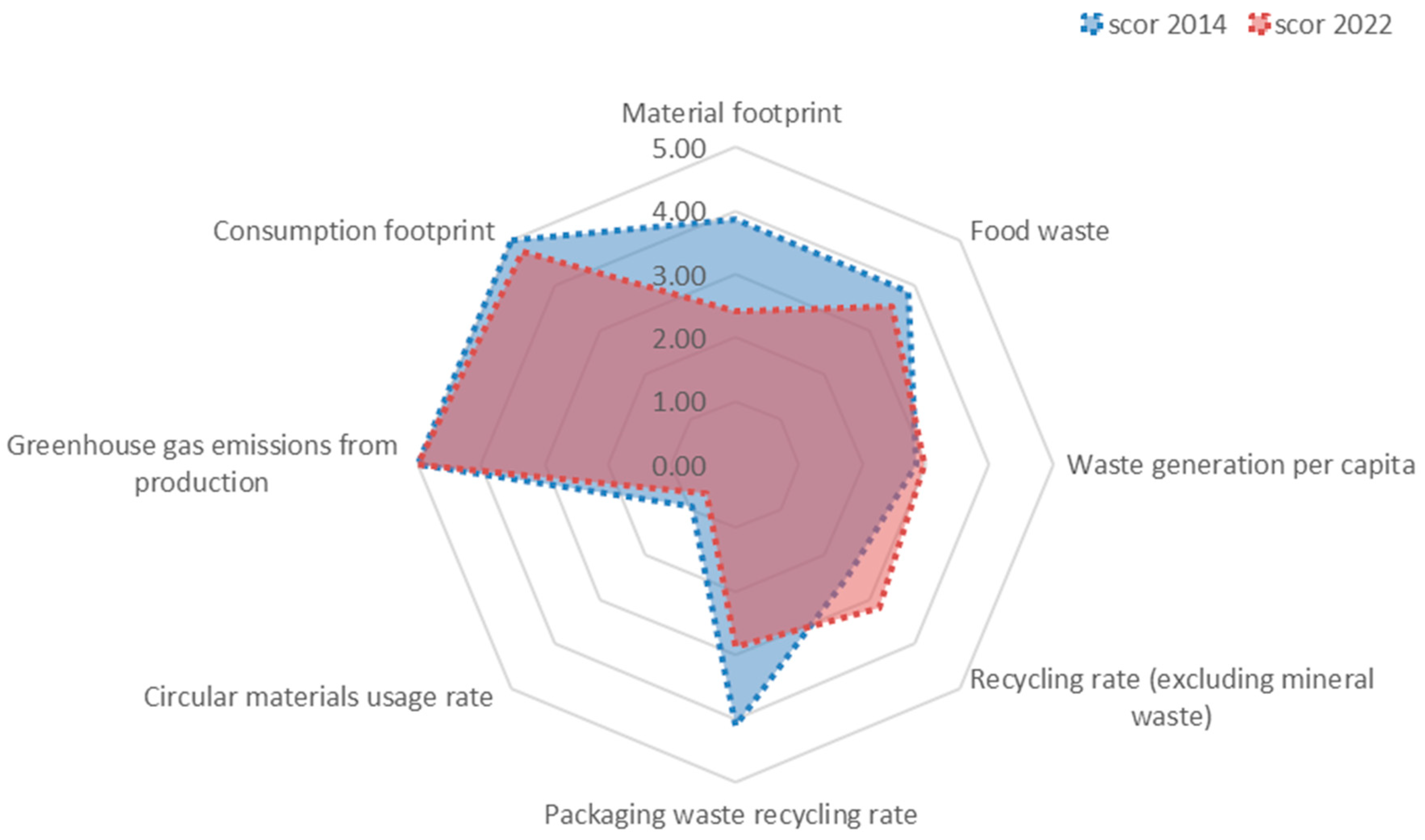

In conclusion, between 2014 and 2022, Romania recorded some notable improvements (

Figure 4), in particular:

Efficiency in waste generation per GDP,

Increase in exports of recyclable materials,

Intensification of innovation in circularity.

However, these advances are overshadowed by stagnation or regression in essential areas such as private investment, the use of circular materials, and added value generated by the circular sector. Romania’s profile remains fragmented, with good performance on sustainability and trade, but without internal economic consolidation of the circular model.

The detailed results for each dimension are presented below, highlighting the progress, regression, or stagnation recorded in the analyzed interval (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

3.1. Economic Dimension

Between 2014 and 2022, Romania’s average score on the economic dimension increased slightly, from 2.12 to 2.19. This marginal evolution indicates a general stagnation, without significant leaps in circular economic development. Although progress was recorded in terms of the number of patents and gross value added, the other components—private investment and resource productivity—remained at low levels or even regressed. This confirms that the circular economy is not yet perceived as a solid economic opportunity and that active policies are needed to stimulate private sector involvement and increase the economic value generated by circular activities.

3.2. Environmental Dimension

The average score for the environmental dimension decreased from 3.52 in 2014 to 3.17 in 2022, indicating a slight but significant regression in an area considered crucial for the green transition. Although Romania maintained its good performance in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and material footprint, other components, such as packaging waste recycling and the use of circular materials, recorded clear decreases. These trends suggest a lack of consistent progress in recycling infrastructure and in the reintegration of resources into the economy, despite increasing European pressure on Member States in the field of sustainable resource management.

3.3. Social Dimension

The most visible improvement is recorded in the social dimension, where the average score increased significantly, from 3.77 to the maximum score of 5.00. This reflects important improvements in indicators such as waste intensity relative to GDP, trade in recyclable raw materials, and reduced dependence on raw material imports. These results suggest that Romania has become more resilient in terms of material flows and has managed to consolidate its position in resource circulation chains at European and global levels.

3.4. Circular Performance Index

The total value of the circular performance index increased from 3.14 in 2014 to 3.45 in 2022, reflecting overall progress, but with a slow pace and an unbalanced nature between the dimensions. While the advance in the social dimension is clear and consistent, the economic and environmental dimensions lag, confirming the observations in the specialized literature [

12,

13] on the fragmented nature of the progress of circularity. This combination of achievements and vulnerabilities highlights that Romania has a solid foundation in terms of material resilience and macroeconomic positioning but needs targeted policies and investments to fully capitalize on the economic and ecological opportunities of the circular economy.

Furthermore, two sensitivity checks were performed to test the robustness of the composite index to alternative weighting schemes. When the economic dimension received 50% of the weight, the overall index declined (2.88 in 2014; 3.14 in 2022), but the interpretation remained consistent with the baseline (

Table 4). Romania showed modest progress but persistent weaknesses in economic performance. Conversely, when the social dimension was weighted at 50%, the index increased (3.30 in 2014; 3.84 in 2022), emphasizing Romania’s strong performance in resilience and material circulation(

Table 4). These scenarios confirm that the study’s main conclusions, namely, a fragmented transition with social strengths and economic weaknesses, are robust to different weighting assumptions.

4. Discussion

To provide context to the results, it is important to provide some structural evolution of Romania’s economy in the past decade, especially with agriculture in the economic growth model, as an overview. According to the National Institute of Statistics, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries represented a contribution of about 5.6% of Romania’s GDP in 2014; however, this contribution decreased to approximately 4.5% in 2022. On the civil employment by activity side between 2014–2022, about 27.3% and 10.9% of the employed population was in agriculture (forestry and fishing included) [

42]. As seen across these waves, there was a gradual decline in direct outcome value-sharing of agriculture in Romania’s economy, while at the same time, there were social and structural vulnerabilities, in particular in rural areas with weak infrastructure and reliance on primary production. This structure ultimately illustrates the fragmented circular performance diluted in the multi-criteria analysis. Despite possessing a strong agricultural foundation and valuable biological resources, the agricultural landscape of smallholdings, poor aggregation ability, and incomplete institutional support limit future investment and the relative scale of circular adoption.

Therefore, the processes of circular transition in the agri-food system of Romania need to provide a balance of resource availability and systemic capability of the feeding systems of the economy with economic efficiencies while providing for social inclusion and institutional capacity.

Our findings show that Romania has made progress in waste efficiency and innovation but still performs poorly in private investment and circular material use. Compared to other similar studies, the results obtained here are distinguished by the simultaneous integration of economic, social, and environmental dimensions in a unified framework, as well as by adapting the methodology to relevant indicators for the agri-food sector. This approach allowed a comparison with the European Union average, and, at the same time, identification of areas where interventions can have the greatest impact.

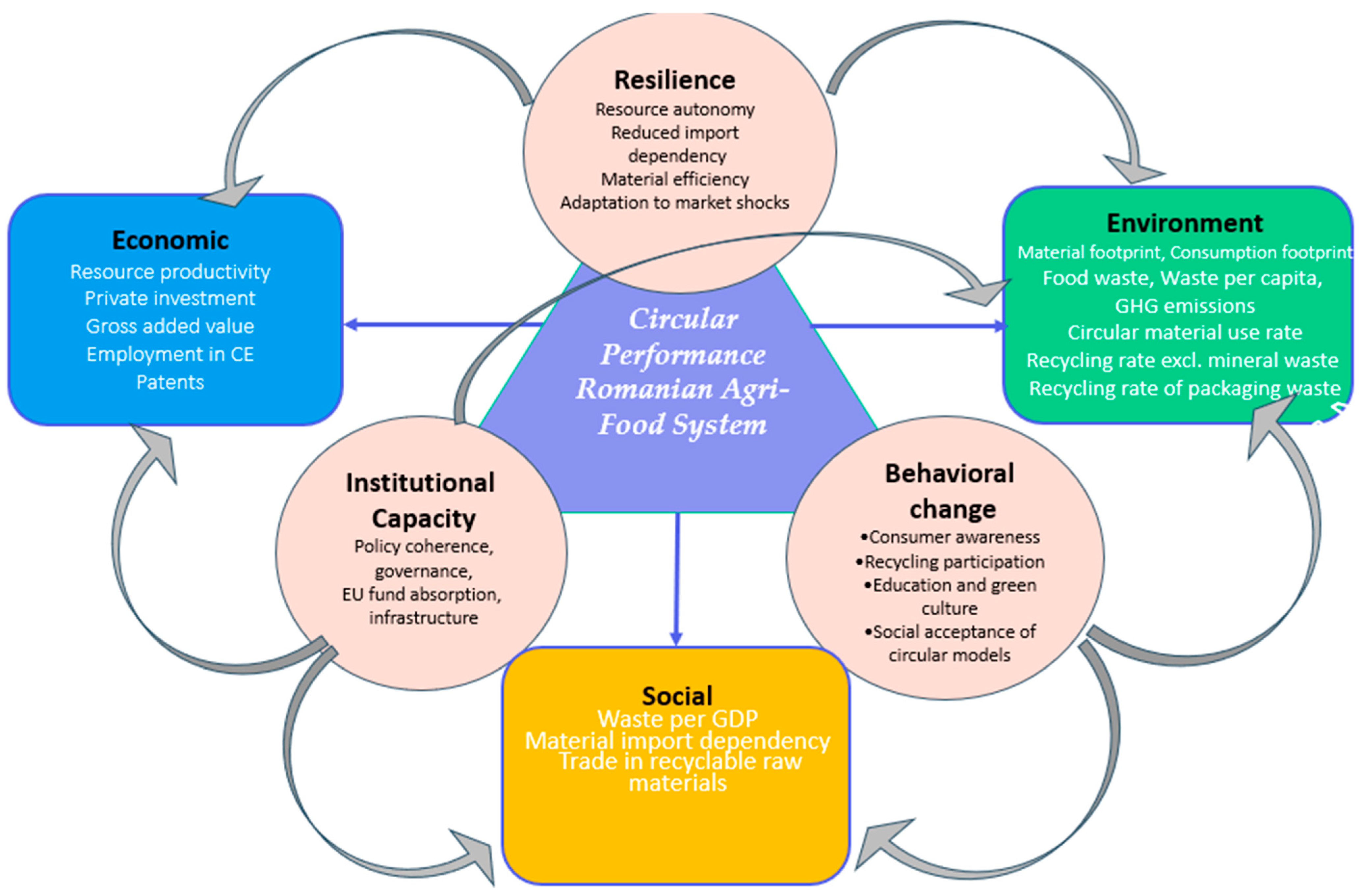

To synthesize the key findings and provide an integrated interpretation,

Figure 8 illustrates the conceptual framework linking Romania’s circular economy performance in the agri-food system with its main systemic drivers. The framework connects the three analytical dimensions—economic, environmental, and social—with the underlying enablers of resilience, institutional capacity, and behavioral change, highlighting how structural and behavioral mechanisms jointly shape circular transition outcomes.

When interpreted through this framework, these findings suggest that Romania’s circular transition is primarily constrained by three interrelated mechanisms. Resilience remains externally dependent, with material autonomy improving but still vulnerable to global supply fluctuations. Institutional capacity is uneven, as policy continuity and administrative efficiency have limited the consistent implementation of circular measures. Behavioral change, although emerging, is influenced by factors such as limited consumer awareness, uneven participation in recycling schemes, and the slow diffusion of green consumption habits. These behavioral barriers, combined with weak incentive mechanisms, continue to constrain the adoption of circular practices at a systemic level. This triad of factors explains why progress in social resilience indicators outpaces that in economic and environmental dimensions, indicating a partial rather than systemic transition.

Overall, this kind of interpretation emphasizes the need to align analytical frameworks with Romania’s structural and institutional context. The following discussion therefore turns to methodological aspects that can better capture these interdependencies.

The persistent decline in private investment in circular activities can be attributed to several structural and institutional barriers. Romania’s agricultural sector remains dominated by small and fragmented farms, which limits capital accumulation and reduces incentives for large-scale circular projects [

32]. In addition, policy instruments to stimulate green entrepreneurship are still underdeveloped, and delays in EU funds absorption have created uncertainty [

9,

33].

Similarly, the low and declining use of recycled materials reflects infrastructural and behavioral constraints, such as uneven development of selective collection and recycling facilities across regions and limited consumer awareness [

36]. These barriers explain why Romania lags behind the EU average despite progress in certain indicators.

In addition to economic and infrastructural barriers, behavioral aspects also play a role. Low levels of consumer awareness and participation in recycling schemes, coupled with the late introduction of incentive mechanisms such as deposit–return systems, have limited the reintegration of secondary raw materials into the economy. While similar challenges are observed across several Central and Eastern European countries, in Romania, these constraints are more pronounced due to weaker demand-side drivers, which further explains the gap compared to the EU average [

11,

27,

36].

These structural, infrastructural, and behavioral constraints highlight the need for refined analytical tools that can capture not only outcomes but also the trade-offs behind them. In line with this, the specialized literature on the assessment of the circular economy identifies several methodological controversies that are also relevant to our analysis [

43]. One of these concerns the complexity of the set of indicators. Some authors argue that an extended set better captures the diversity of circular processes, while others warn that too many indicators can complicate the analysis and reduce the readability of the results. Another debate concerns the weighing of economic, social, and environmental dimensions, either treated equally to reflect the principles of integrated sustainability, or with a greater emphasis on the economic component, with the idea of accelerating the adoption of circular practices. There are also differences of opinion on the use of relative or absolute indicators: the former allows comparability between countries, while the latter better highlights internal progress and real impact. Even the meaning of performance can generate different interpretations, with a high value for a “positive” indicator being associated with progress but potentially masking the lack of policies to reduce consumption at source. Finally, the degree of aggregation of the final score is another sensitive point: a single index facilitates communication and comparability, but can hide major imbalances between dimensions [

44,

45]. The convergence of mechanisms for increasing technical efficiency and eco-efficiency justifies the inclusion of circular economy indicators in a multi-criteria sustainability analysis, to guide interventions towards simultaneously superior economic and environmental results [

46].

Our analysis took these challenges into account, choosing a balanced set of indicators, equal weights for dimensions, and a transparent calculation method, precisely to ensure the relevance and comparability of results at the European level [

47].

The results of Remeikienė, Gasparėnienė, and Bankauskienė (2025) highlight the fact that, at the European Union level, the indicators with the greatest significance in assessing the circular economy are the material footprint, patents related to waste management and recycling, and dependence on raw material imports [

48]. In contrast, intra-EU trade and private investment are perceived as criteria of low importance. In all multi-criteria methods applied, Romania was placed in the group of countries with the lowest level of the circular economy, together with Bulgaria, Estonia, and Finland. This result confirms the findings of our analysis, in which the economic and environmental dimensions present modest scores, and progress is concentrated mainly in the area of material resilience. Their study supports the idea that, for a real transition, there is a need to stimulate innovation, implement eco-design, and strengthen cooperation between the business environment, authorities, and academia, elements that Romania must systematically develop in order to improve its position in the European rankings [

48].

D’Adamo, Favari, Gastaldi, and Kirchherr (2024) conducted a comparative analysis of the performance of the circular economy in the member states of the European Union, highlighting differences between the countries in Western Europe, which are at the top of the rankings, and those in the East, including Romania, which, although below the European average, have a significant potential for recovery [

49]. The authors emphasize that private investment and the added value generated by circular sectors are key factors of progress, and to accelerate the transition, investments in circular technologies, human capital, and start-ups are needed, as well as the active involvement of consumers and transnational cooperation. This context confirms that, through well-targeted measures, states currently lagging behind the EU average can quickly reduce gaps and capitalize on specific opportunities [

49].

Kravchenko, McAloone, and Pigosso (2020) highlight that circular economy indicators do not always fully capture the sustainability dimension, with gaps in terminology, parameter selection, and integration with Triple Bottom Line (TBL) indicators [

50]. In the context of our study on the Romanian agri-food system, these findings support the need for a methodology that correlates circular performance not only with resource efficiency, but also with economic, social, and environmental impacts, thus ensuring a holistic and comparable assessment at the European level [

50].

Compared to the findings of Martinho (2021), which highlight the lack of standardization and underrepresentation of economic and social dimensions in the assessment of the circular economy [

13], our multi-criteria analysis applied to the Romanian agri-food system explicitly integrates these dimensions alongside the environmental one, thus providing a more balanced framework and a more solid basis for comparisons at the European level.

The findings of Santiago Muñoz, Hosseini, and Crawford (2024), which propose a measurement system based on the full spectrum of the 9Rs of the circular economy, highlight the importance of capturing all dimensions and avoiding often-neglected rebound effects [

51]. In comparison, our multi-criteria analysis of the Romanian agri-food system integrates a selective set of indicators relevant to the national context and for comparison with the EU average but does not exhaustively cover all 9R strategies. This difference suggests the opportunity to expand the assessment framework used in Romania to include additional dimensions and reduce the risk of partial conclusions on the progress of circularity [

51].

Elia, Gnoni, and Tornese (2017) show that the evaluation of circular economy strategies through index-based methods represents a relevant research direction, aimed at overcoming the fragmentation of indicators and the lack of methodological coherence [

52]. In their study, the authors propose an analysis framework and select existing methodologies to assess circular performance according to the requirements and objectives of the EC strategy, an approach that, similar to our multi-criteria analysis applied to the agri-food sector in Romania, combines multiple indicators to capture the essential dimensions of circularity. This methodological convergence confirms the relevance of using an integrated framework, capable of providing comparable results and applicable in different national contexts [

52].

These differences in approach highlight the fact that there is no single and universally accepted formula for constructing a multi-criteria analysis in the circular economy. The choice of the set of indicators, the weighing of dimensions, the use of relative or absolute data, and the way of presenting the results depend on the objectives of the study, the target audience, and the availability of data. In the context of the circular bioeconomy, where the complexity of interactions between systems is high, the balance between methodological rigor and clarity of communication becomes essential for the relevance and usefulness of the analysis [

53,

54].

Therefore, adapting the national monitoring framework to integrate the full evaluation of the 9R strategies, as proposed by Santiago Muñoz et al. (2024), could improve the accuracy of circular performance measurement and provide a more solid basis for public policies oriented towards sustainable transition [

51].

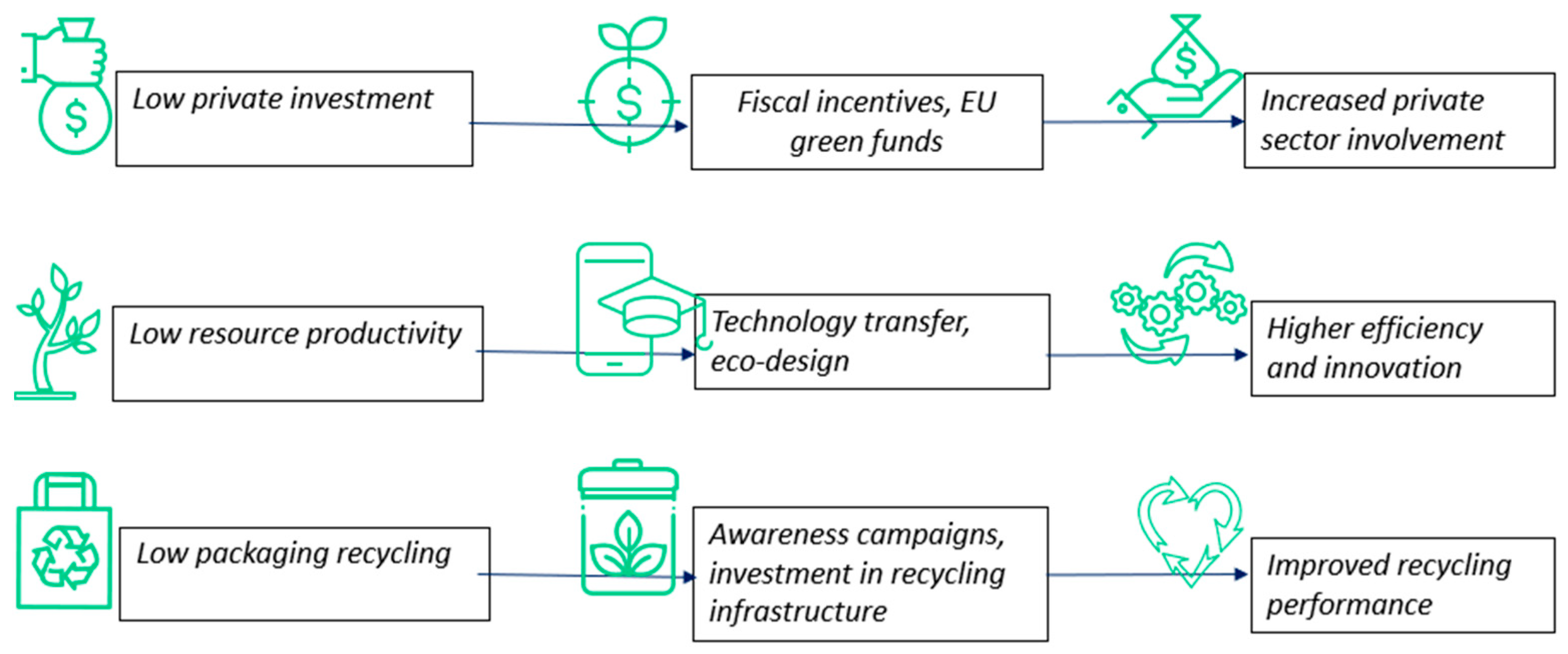

Overall, the convergence of the conclusions from the specialized literature with the results of our analysis confirms not only the accuracy of the current diagnosis but also the existence of clear directions for accelerating the transition to the circular economy in Romania. To translate the analytical findings into practical directions,

Figure 9 outlines the main pathways through which the identified weaknesses can be mitigated by targeted interventions, consistent with EU circular economy policy priorities.

Although the gaps compared to the EU average remain visible, the specific progress and the potential identified in key areas demonstrate that, through strategic measures and trans-national cooperation, these differences can be reduced in a relatively short period of time, transforming the circular economy from a challenge into an opportunity for sustainable development.

This study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the results. First, the selection of indicators relied on data availability and agri-food relevance. As a result, some relevant variables (e.g., sector-specific waste streams and detailed innovation measures) could not be included, which narrows the coverage of the index. Second, the use of a composite index inevitably involves methodological assumptions regarding normalization, coding of “higher-is-better/lower-is-better” indicators, and weighting. Although sensitivity analyses show that the main findings are robust, alternative coding rules or weighting schemes may yield slightly different absolute values. Third, Eurostat indicators often capture general circular economy dynamics and may not fully reflect agri-food specificities (e.g., patents and private investment). In this study, they were treated as proxies, ensuring comparability with EU benchmarks, while recognizing the need for future research to develop more sector-specific circular economy metrics. Finally, the analysis is descriptive and comparative but does not establish causal mechanisms between circular economy performance and underlying policies or investments.

Finally, it is acknowledged that the research questions developed in this study allow for primarily descriptive research that yields a starting point of circular economy performance in the Romanian agri-food system. This decision is influenced by the lack of specific data in the sector as well as the emergent nature of the topic. However, the results presented herein led to the identification of several structural and policy-related barriers, namely, low private investment, insufficient recycling infrastructure, and differential levels of EU fund utilization. Future research could build on these results to employ causal inference methodologies, such as econometric modeling or policy evaluation, in order to identify trade-offs between economic competitiveness, environmental performance, and social resilience.

5. Conclusions

The multi-criteria analysis of indicators grouped by economic, environmental, and social dimensions highlights an uneven evolution of Romania’s circular performance in the period 2014–2022. Although the overall composite index increased from 3.14 to 3.45, progress was moderate and uneven, with clearly differentiated trends between the three major areas of sustainability.

The economic dimension remains the vulnerable point of the circular transition. The average score increased only marginally, from 2.12 to 2.19, signaling a reduced capacity for the economic valorization of circular principles. Despite an advance in innovation (patents) and a slight increase in gross value added, private investment and resource productivity remain significantly below the EU average. This stagnation suggests that political and financial support for circular entrepreneurship and technology transfer is still insufficient.

In the environmental dimension, the score decreased from 3.52 to 3.17, indicating a deterioration in environmental performance, despite stability in some aspects (emissions and material footprint). The main causes are the regression in packaging recycling and in the use of circular materials. These results reflect deficiencies in the collection infrastructure, lack of consumer motivation, and insufficiently calibrated support policies to effectively close resource cycles.

In contrast, the social dimension recorded a substantial increase, from 3.77 to 5.00—reaching the EU reference level. This jump is the result of a clear improvement in the system’s resilience: reducing waste intensity, strengthening trade in recyclable raw materials, and decreasing dependence on imports. Romania thus seems to have reached a strategic maturity in managing material flows, which is not yet supported by a commensurate performance in the other two dimensions, however.

The results suggest that Romania has the potential for circular convergence with the EU, but the transition is still asymmetric and partial. To support an integrated and competitive circular economy, it is essential to strengthen policies to stimulate private investment in green technologies; to accelerate reforms in collection and recycling infrastructure; and to intensify measures to educate and engage consumers and local actors.

Integrating circular sustainability into sectoral strategies, especially in the agri-food sector, will be crucial for Romania to transform social progress into sustainable economic and environmental impact.

Beyond generic policy directions, Romania faces several structural barriers that must be addressed to accelerate the circular transition in the agri-food system. First, the persistence of highly fragmented farms limits economies of scale and the adoption of resource-efficient technologies. Second, waste management infrastructure remains underdeveloped, especially in rural areas, hindering selective collection and effective recycling. Third, the absorption of EU funds is often slowed by administrative capacity gaps, which reduces the impact of available financial instruments. Fourth, private sector involvement is limited, as current incentive schemes for green investment and eco-innovation are weak. Addressing these barriers through cooperative structures, targeted infrastructure programs, simplification of funding procedures, and stronger fiscal incentives for circular entrepreneurship would provide Romania with a more robust foundation for circular agri-food development.

The proposed multi-criteria model from this study serves as an actionable tool for analyzing the circular performance of agri-food systems at the national level. By converging economic, social, and environmental dimensions to a single comparable framework, it allows policymakers to identify structural bottlenecks and interventions in line with the EU circular economy priorities. The model can be generalized for other relating EU emerging economies, facilitating or leading to evidence-based drivers of the circular transition in agri-food systems.

At a theoretical level, this study contributes to the advancement of the analytical framework of circular economy assessment by establishing a link between the economic, social and environmental pillars with the systemic enablers of resilience, institutional capacity, and behavioral change. Such a perspective adds to the existing models used for assessing circularity by stressing the interdependencies that exist with respect to behavioral and structural factors of change, thus creating a bridge in conceptual terms between macro level indicators and micro level transition drivers in the agri-food system.

At a practical level, the results suggest several targeted policy implications. Beyond the needs of improving infrastructural development and funding mechanisms, Romania should pursue the development of regional circular clusters that link farmers, processors and recyclers to enhance recirculation of resources and nutrients. The introduction of tax incentives and green public procurement schemes could serve to enhance private investment in circular technologies. Capacity building programs would enhance the circular transition as well. Last, but not least, the strengthening of the monitoring of data systems regarding material flow and waste movements would serve to enhance public policy development and accountability.