Research on Strawberry Visual Recognition and 3D Localization Based on Lightweight RAFS-YOLO and RGB-D Camera

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A lightweight RAFS-YOLO model is constructed based on YOLOv11, which effectively reduces the number of parameters and computational overhead while ensuring detection accuracy;

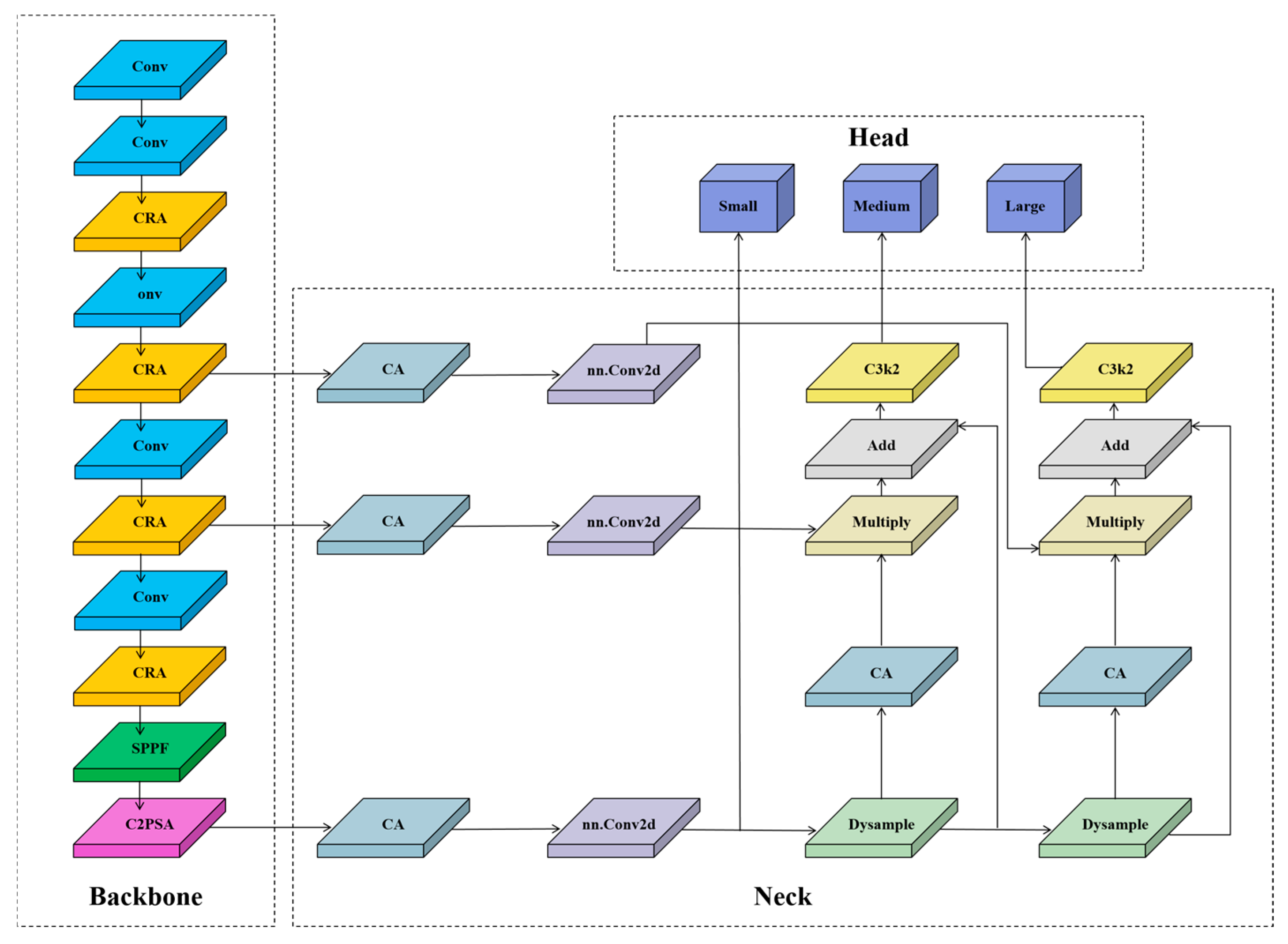

- Three modules—CRA, HSFPN, and DySample—are introduced and improved in the network structure. These modules optimize spatial location modeling capabilities, multi-scale feature fusion, and upsampling efficiency, thereby enhancing the model’s detection robustness and inference efficiency;

- A visual positioning system that combines a detection model with the depth information of an RGB-D camera is constructed, which enables real-time fruit detection and high-precision 3D coordinate output, providing a reliable visual foundation for the automated decision-making of intelligent picking systems.

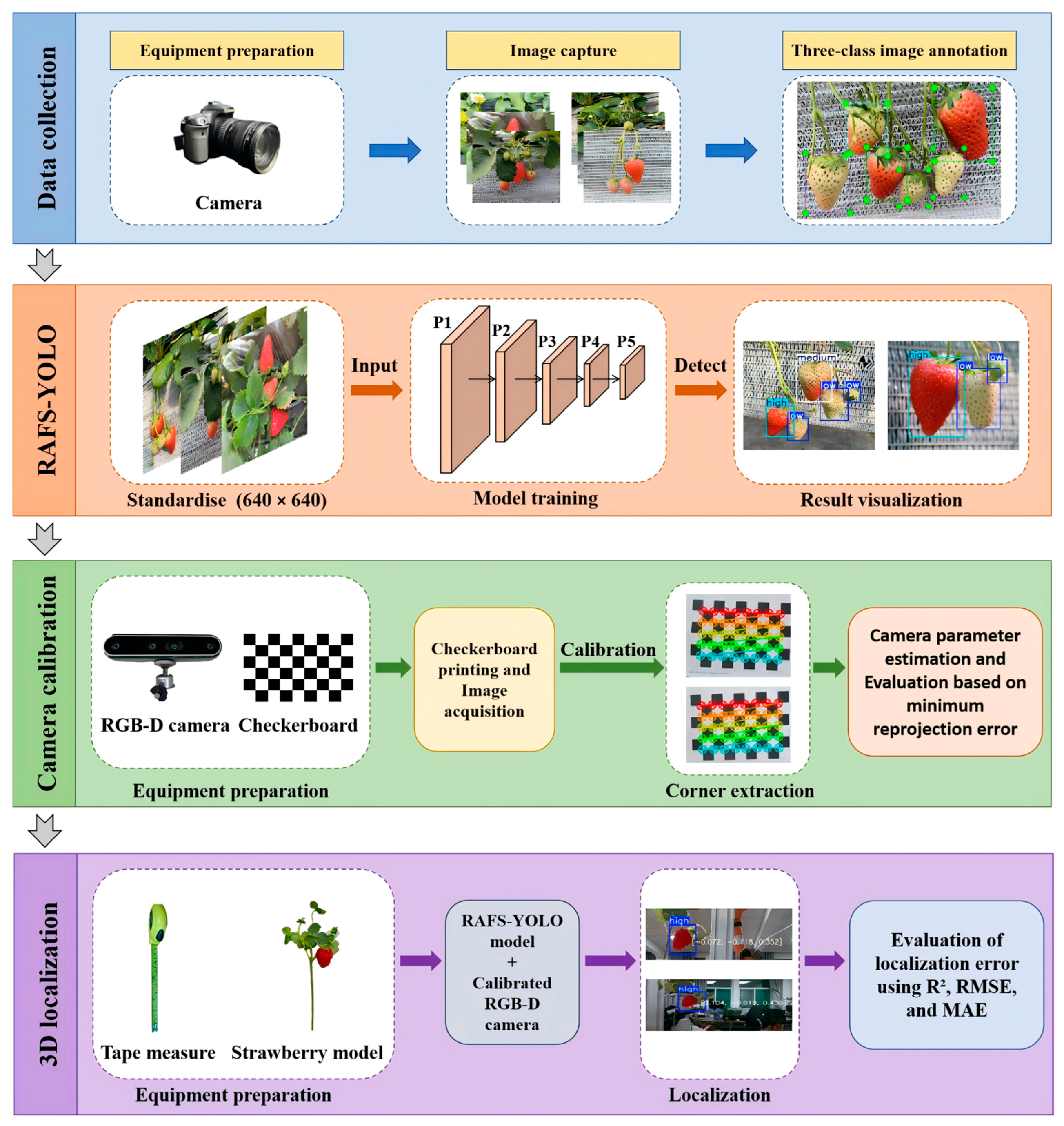

2. Materials and Methods

- Dataset collection and annotation, which is used to construct the basic data resources required for model training and performance evaluation;

- The improved object detection model RAFS-YOLO, which is used to realize the automatic recognition of strawberry fruits and ripeness discrimination in RGB images;

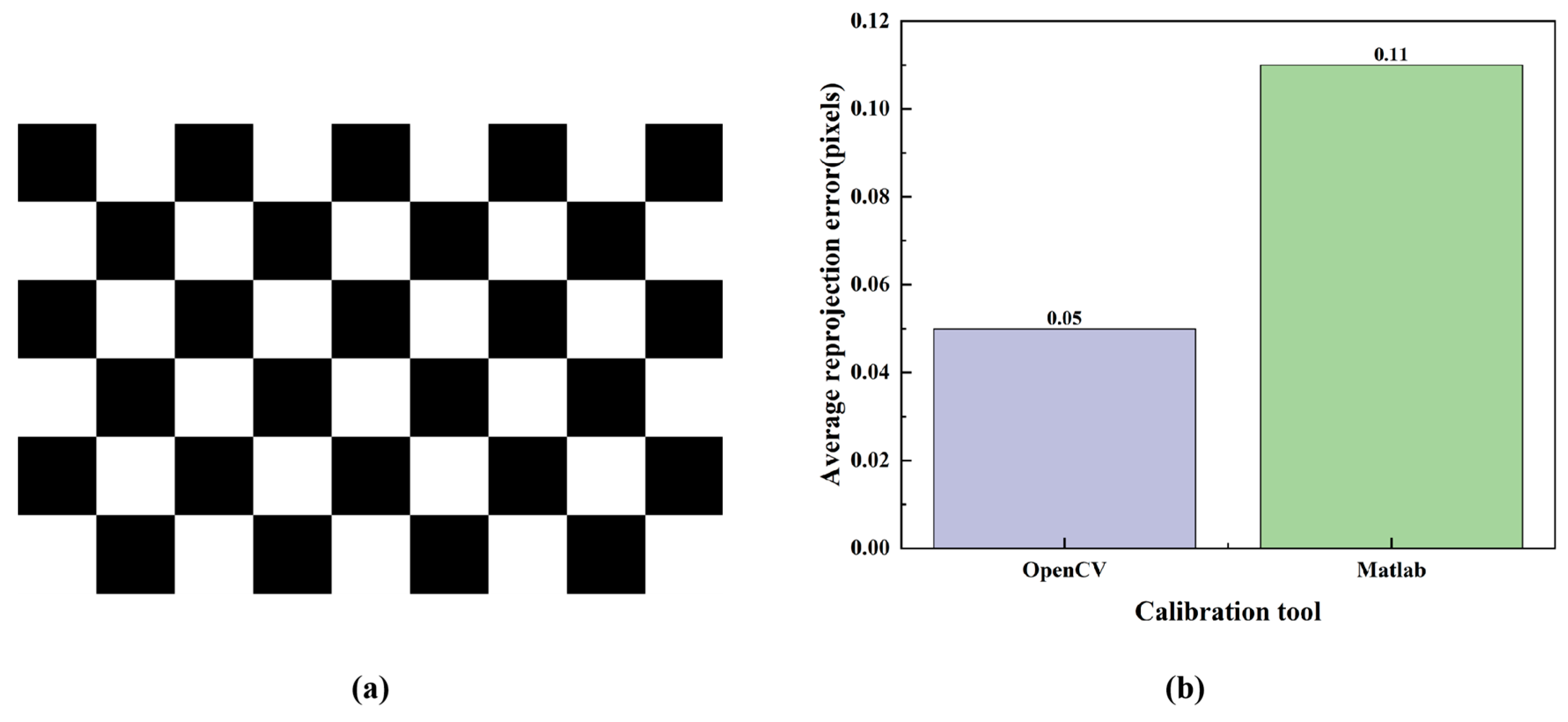

- Camera calibration, which involves accurate calibration of the RGB camera part in the RGB-D camera to ensure the accuracy of 3D spatial localization;

- Spatial coordinate calculation, which maps image pixel coordinates to 3D spatial coordinates based on the depth information provided by the RGB-D camera, thereby achieving the spatial localization of strawberries.

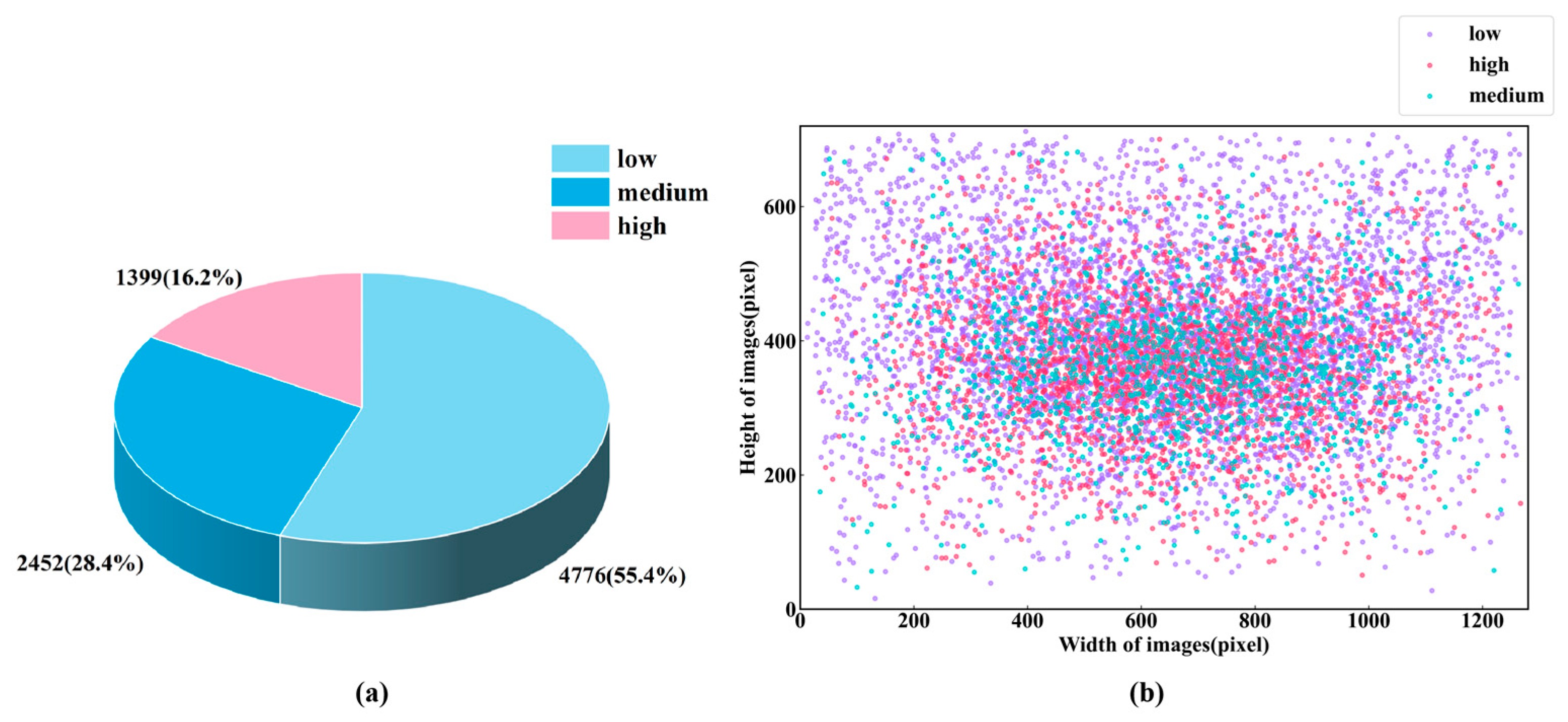

2.1. Dataset and Annotation

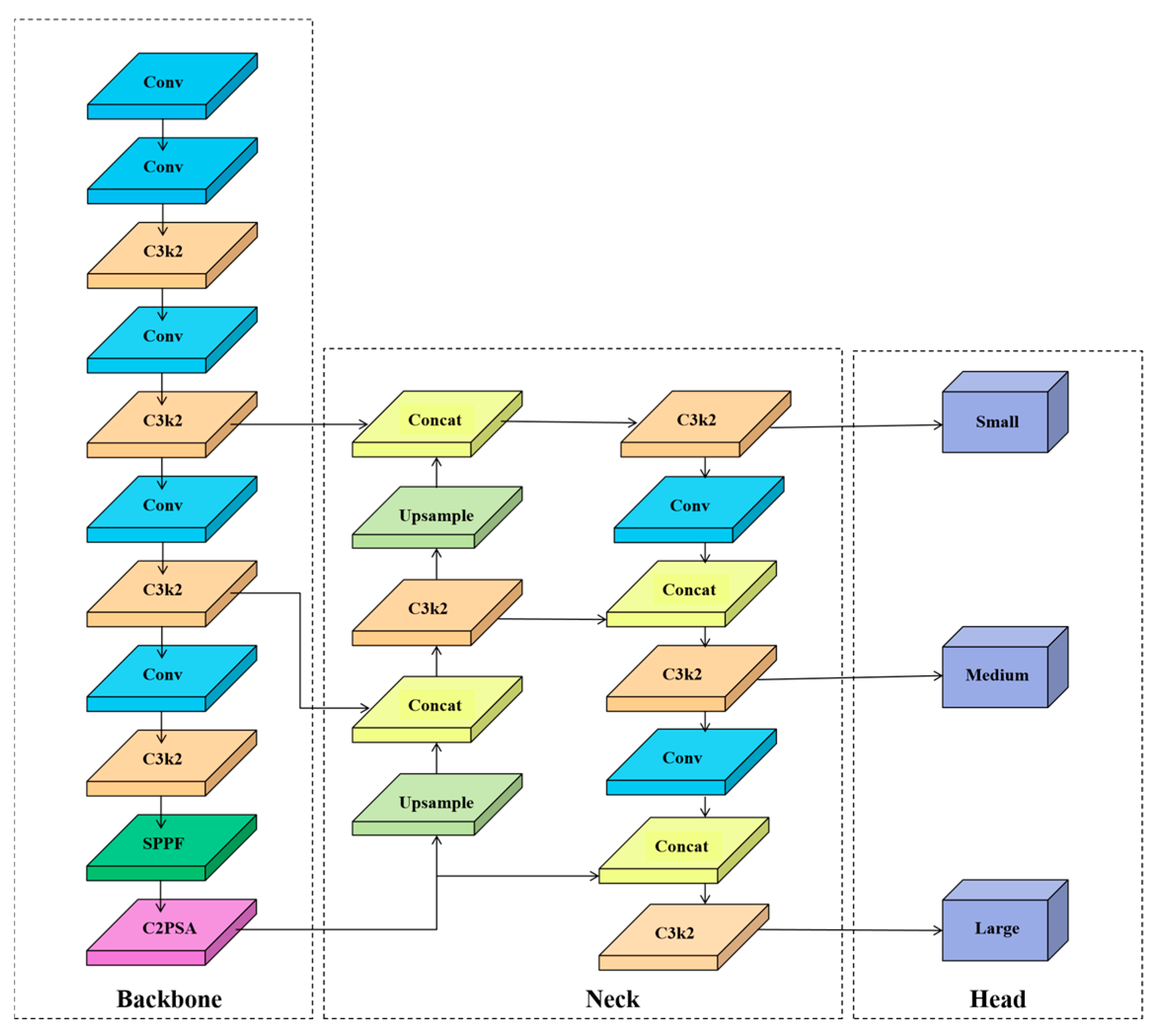

2.2. Overall Architecture of the RAFS-YOLO Model

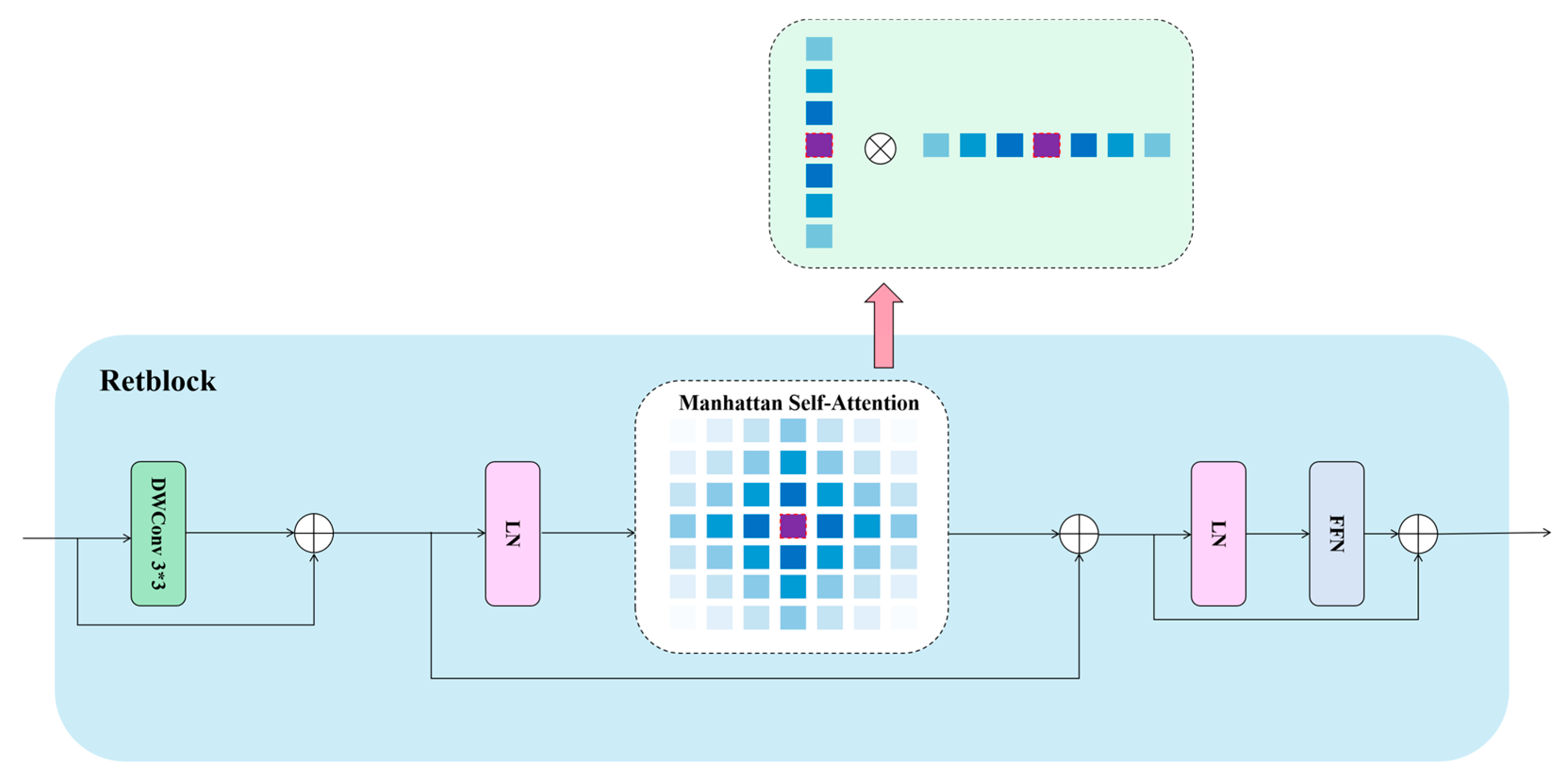

2.3. CRA (Cross-Stage Partial Convolutional Block with Retention Attention)

2.4. High-Level Screening Feature Fusion Pyramid Network (HSFPN)

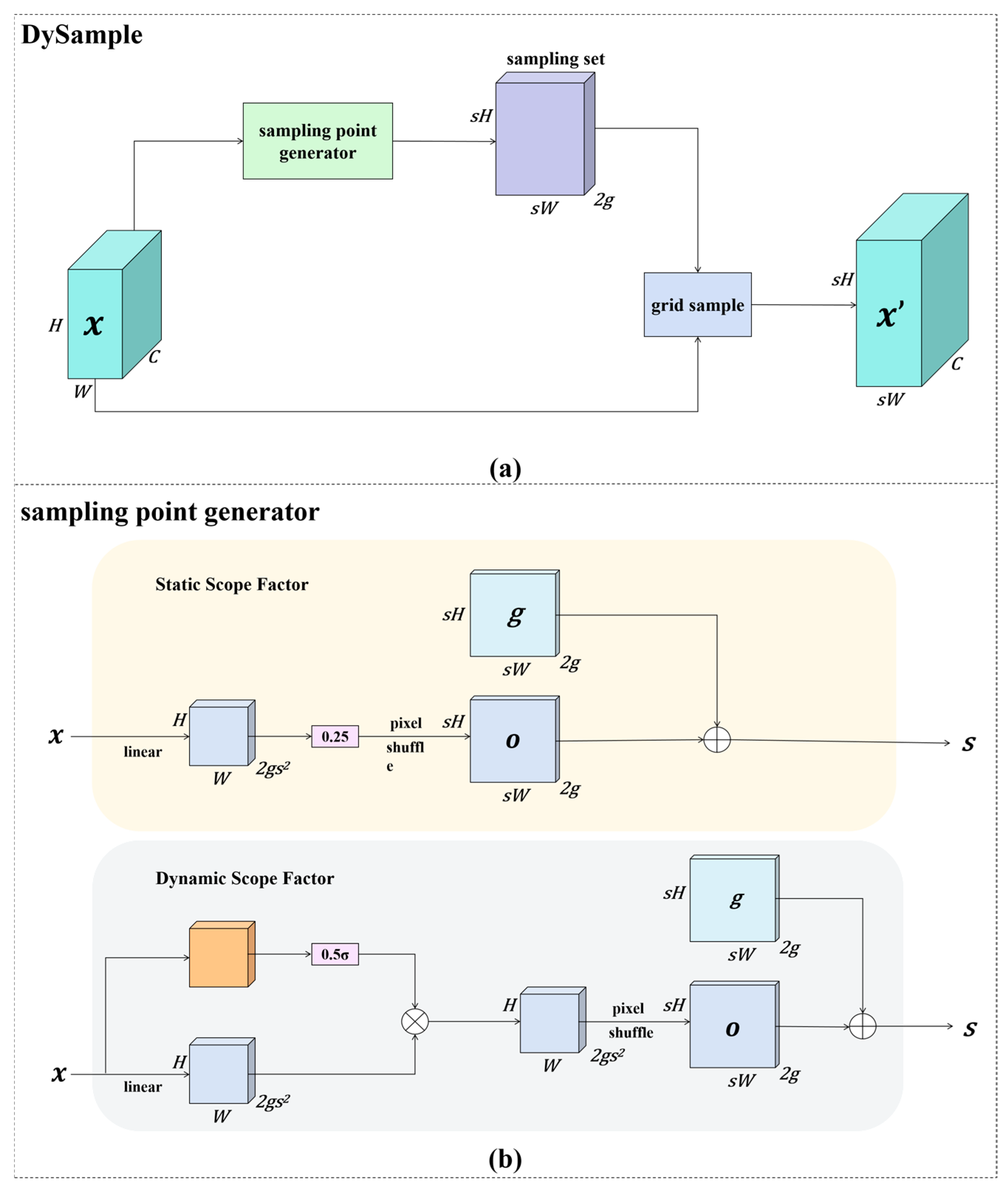

2.5. Lightweight Dynamic Upsampling Module (DySample)

2.6. Three-Dimensional Positioning

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

2.8. Model Training and Implementation Details

3. Results

3.1. Model Selection

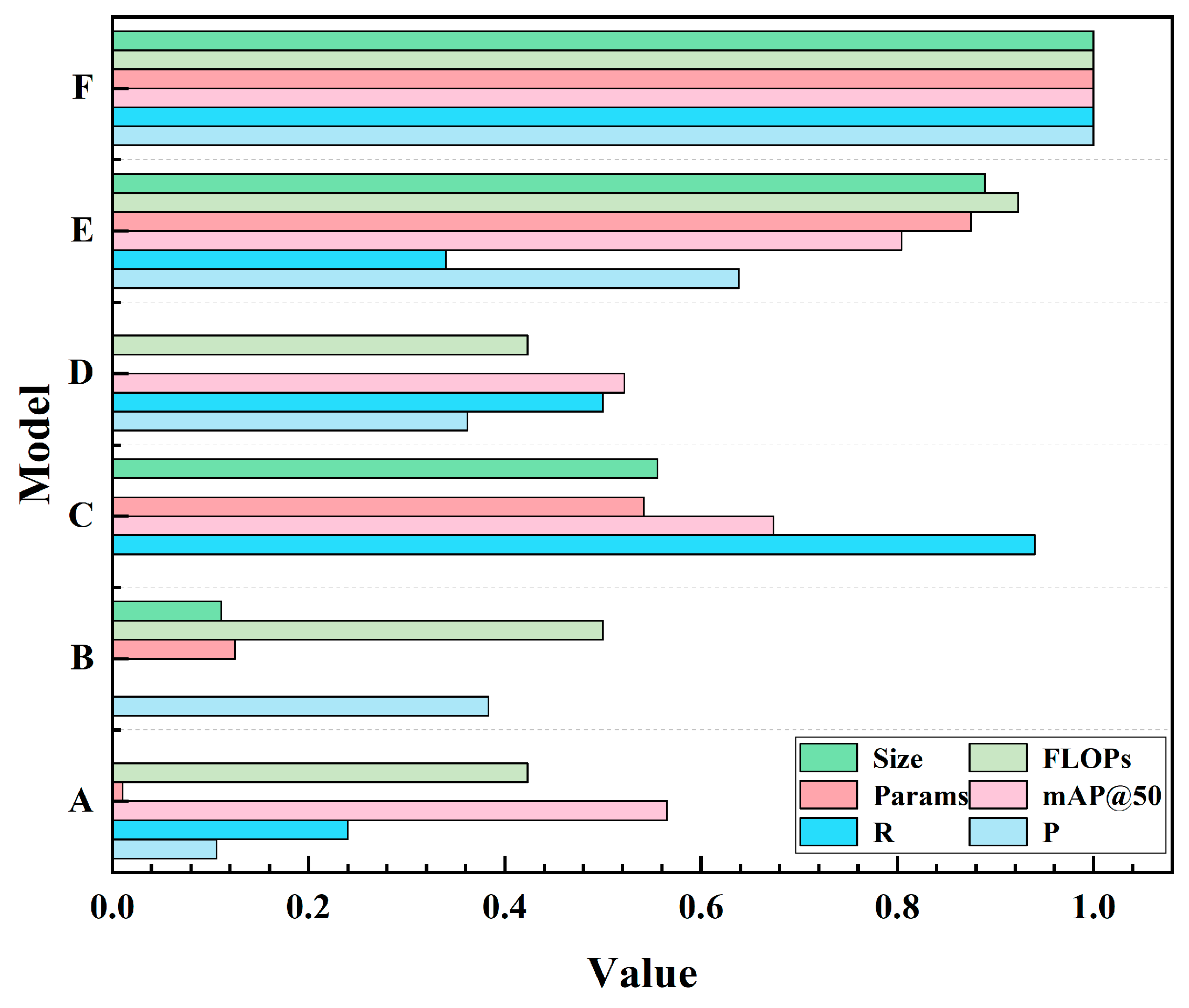

3.2. Ablation Experiments

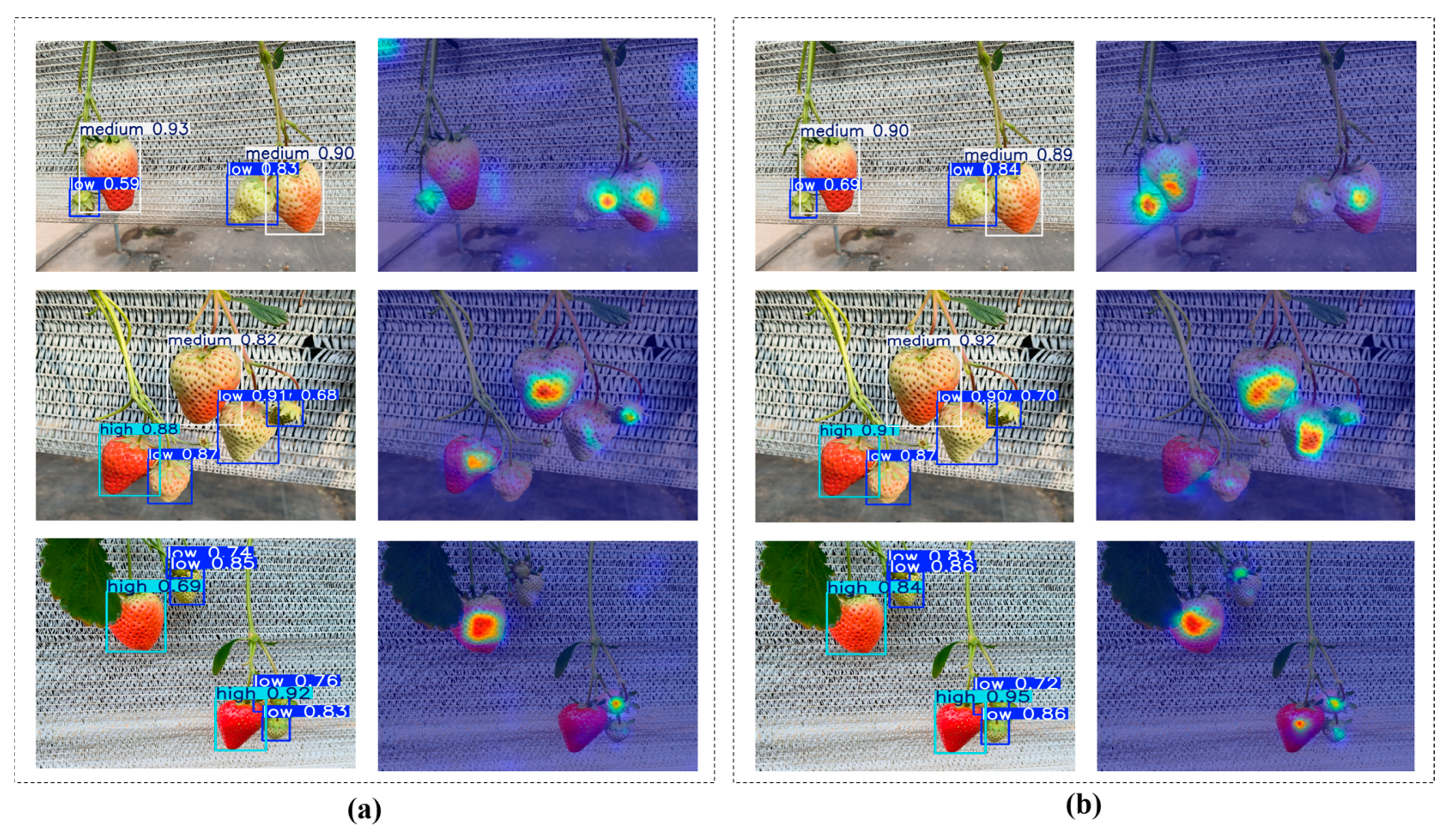

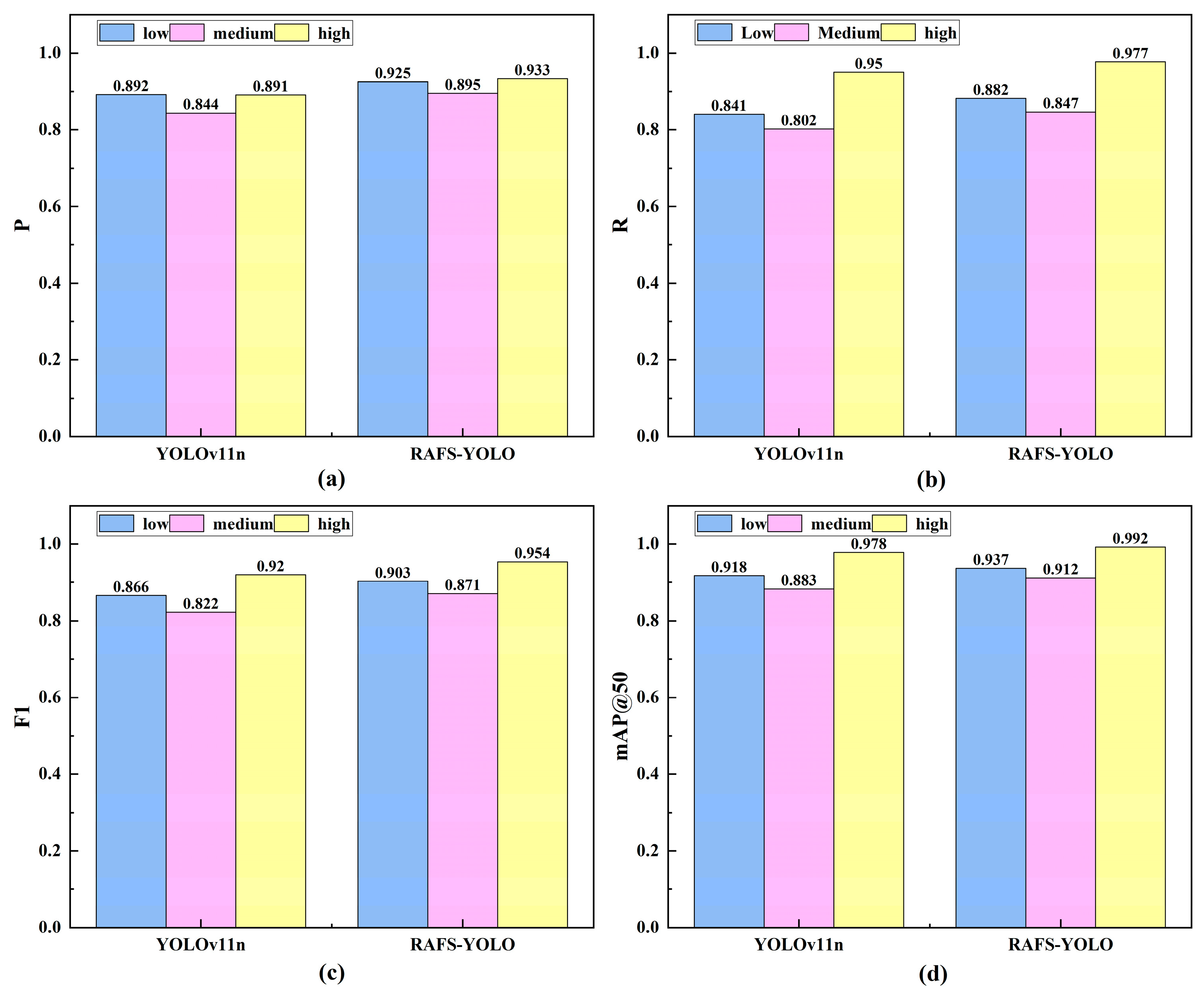

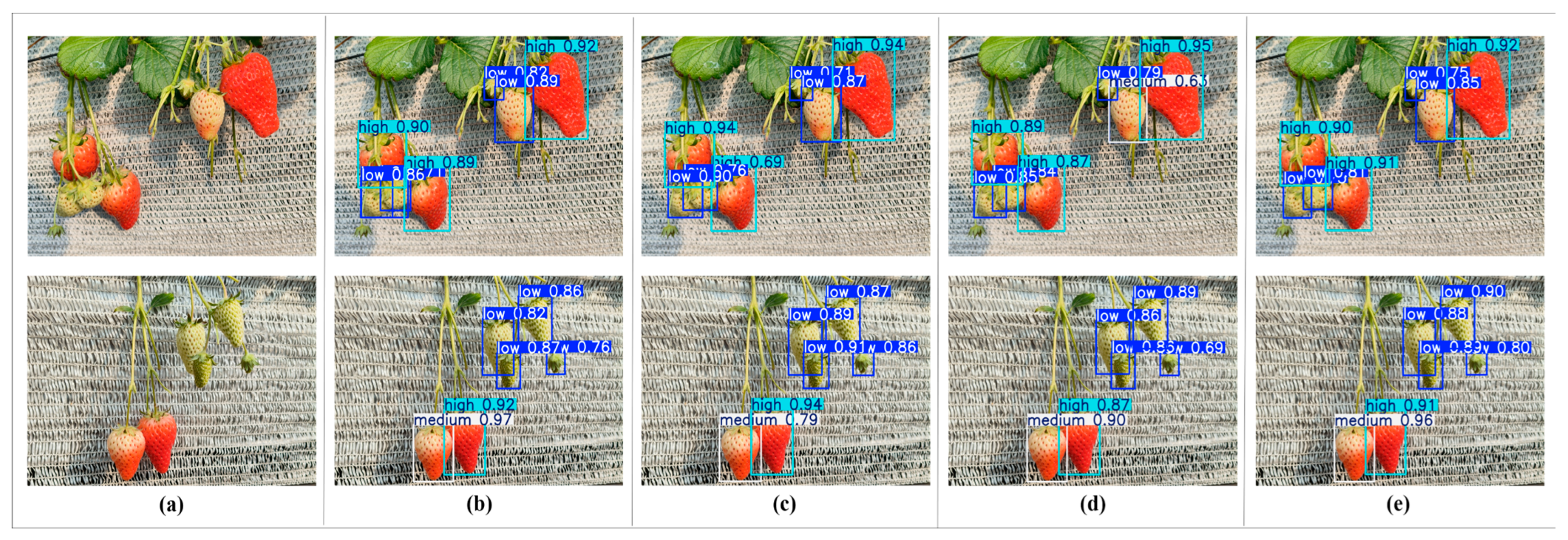

3.3. Analysis of Detection Performance for Different Maturity Categories

3.4. Comparative Experiments

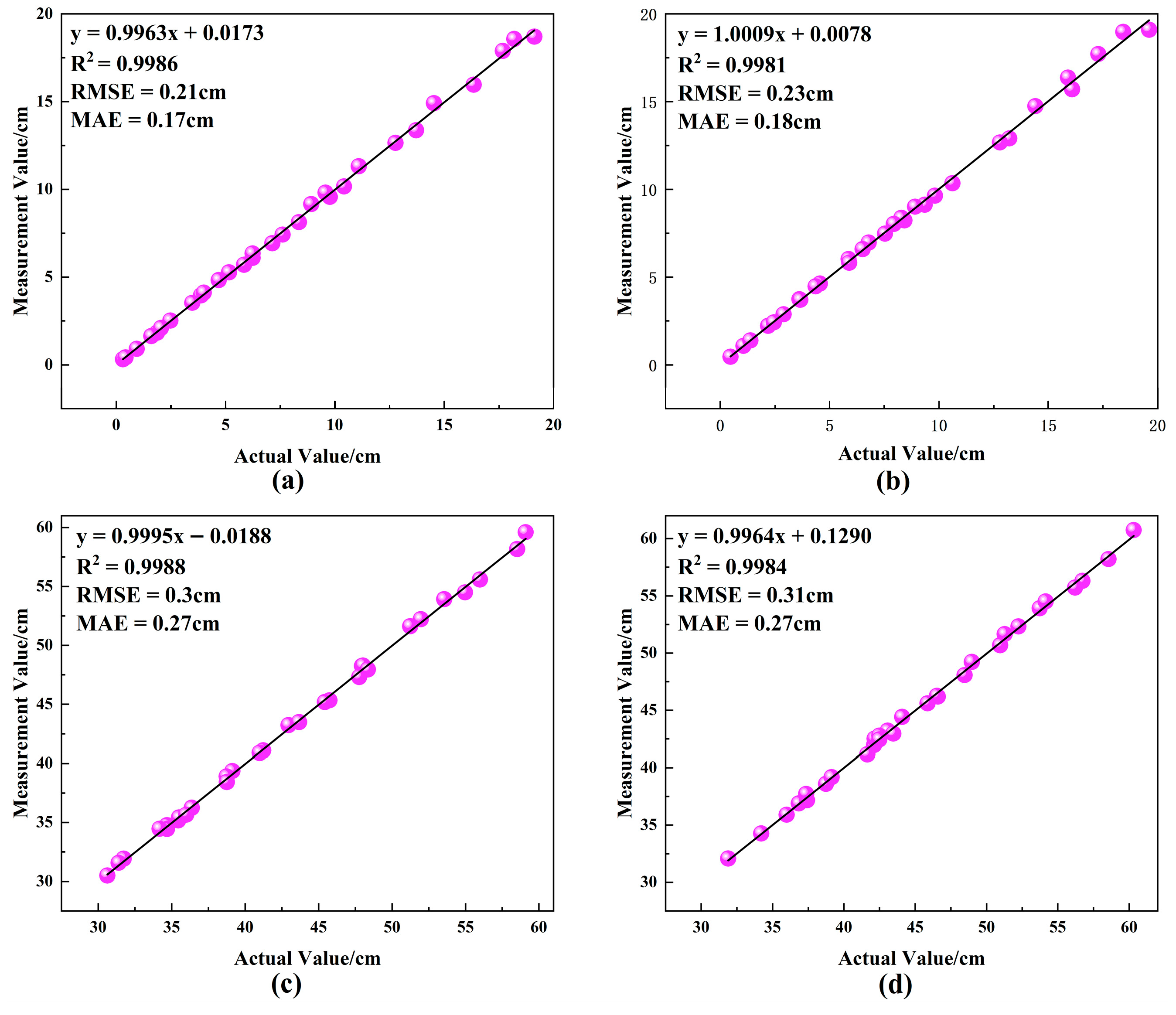

3.5. Results of Spatial Localization Experiment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Kang, N.; Qu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, H. Automatic fruit picking technology: A comprehensive review of research advances. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xu, L. Design, development, integration, and field evaluation of a ridge-planting strawberry harvesting robot. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.; Schreurs, C.; da Silva, A.F.; Pereira, F.; Felgueiras, C.; Lopes, A.M.; Machado, J. Integration of artificial vision and image processing into a pick and place collaborative robotic system. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Leite, A.C.; From, P.J. A novel end-to-end vision-based architecture for agricultural human–robot collaboration in fruit picking operations. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 172, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q. Review of smart robots for fruit and vegetable picking in agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.Z.; Zaman, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.F. Visual servo algorithm of robot arm for pick and place application. J. Kejuruter. 2024, 36, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q. Improving picking efficiency under occlusion: Design, development, and field evaluation of an innovative robotic strawberry harvester. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Gao, S.; Deng, Z. Strawberry ripeness detection based on YOLOv8 algorithm fused with LW-Swin Transformer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosada, R.; Hussein, Z.M.; Novamizanti, L. Evaluating YOLO Variants for Real-Time Multi-Object Detection of Strawberry Quality and Ripeness. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Industry 4.0, Artificial Intelligence, and Communications Technology (IAICT), Bali, Indonesia, 3–5 July 2025; pp. 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Chen, J. Polarization of road target detection under complex weather conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daza, A.; Ramos, K.Z.; Paz, A.A.; Dario, R.; Rivera, M. Deep learning and machine learning for plant and fruit recognition: A systematic review. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2024, 14, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, P.; Raja, P.; Karkee, M.; Raja, M.; Baig, R.U.; Trung, K.T.; Hoang, V.T. Performance analysis of modified deeplabv3+ architecture for fruit detection and localization in apple orchards. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, H.; Shimomoto, K.; Fukatsu, T.; Hosoi, F.; Ota, T. Interoperability analysis of tomato fruit detection models for images taken at different Facilities, Cultivation Methods, and Times of the Day. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1827–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subeesh, A.; Kumar, S.P.; Chakraborty, S.K.; Upendar, K.; Chandel, N.S.; Jat, D.; Dubey, K.; Modi, R.U.; Khan, M.M. UAV imagery coupled deep learning approach for the development of an adaptive in-house web-based application for yield estimation in citrus orchard. Measurement 2024, 234, 114786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Hiraguri, T.; Kimura, T.; Shimizu, H.; Shimada, T.; Shibasaki, A.; Suzuki, C.; Fujinuma, R.; Takemura, Y. Estimation of the amount of pear pollen based on flowering stage detection using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X. Overview of two-stage object detection algorithms. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1544, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntao, X.; Zhen, L.; Linyue, T.; Rui, L.; Rongbin, B.; Hongxing, P. Visual detection technology of green citrus under natural environment. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 49, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Niu, T.; He, D. Tomato young fruits detection method under near color background based on improved faster R-CNN with attention mechanism. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Guo, Z.; Zeng, L. Detection model based on improved faster-RCNN in apple orchard environment. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 21, 200325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.; Gite, S.; Chandekar, H.; Dlima, L.; Pradhan, B. Multi-class fruit ripeness detection using YOLO and SSD object detection models. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Kumar, S.; Verma, A.; Baijal, S.; Dutta, C.; Choudhury, T.; Patni, J.C. Enhancing Fruit Recognition with YOLO v7: A Comparative Analysis Against YOLO v4. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems and Management Science, St. Julian, Malta, 18–19 December 2023; pp. 330–342. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhu, W.; Long, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wu, W. A real-time detection framework for on-tree mango based on SSD network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Applications, Newcastle, NSW, Australia, 9–11 August 2018; pp. 423–436. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, R.; Chen, N.; Yuan, H. A detection algorithm for cherry fruits based on the improved YOLO-v4 model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 13895–13906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, P.; He, C.; Song, Q.; Chen, J.; Kong, X.; Luo, Z. A lightweight and high-precision passion fruit YOLO detection model for deployment in embedded devices. Sensors 2024, 24, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Mo, X.; Wen, S.; Wu, K.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. DNE-YOLO: A method for apple fruit detection in Diverse Natural Environments. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Jujube-YOLO: A precise jujube fruit recognition model in unstructured environments. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ge, Y. Intelligent detection of Multi-Class pitaya fruits in target picking row based on WGB-YOLO network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 208, 107780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; He, D. Channel pruned YOLO V5s-based deep learning approach for rapid and accurate apple fruitlet detection before fruit thinning. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 210, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Duan, F.; Tian, Z.; Han, C. A novel deep learning method for detecting strawberry fruit. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Cheng, H.; Ma, Z.; Lu, W.; Wang, M.; Meng, Z.; Jiang, C.; Hong, F. DSW-YOLO: A detection method for ground-planted strawberry fruits under different occlusion levels. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, G.; Meng, Q.; Yao, T.; Han, J.; Zhang, B. DSE-YOLO: Detail semantics enhancement YOLO for multi-stage strawberry detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, D.; Zou, X. Strawberry detection and ripeness classification using yolov8+ model and image processing method. Agriculture 2024, 14, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, S. YOLOv11-HRS: An Improved Model for Strawberry Ripeness Detection. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Shao, G.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, T. CR-YOLOv9: Improved YOLOv9 multi-stage strawberry fruit maturity detection application integrated with CRNET. Foods 2024, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, S.E.; Alsayyari, M.; Alqahtani, N.; Aldosery, K.; Altaweel, A.; Alzhrani, S. An Intelligent Management System and Advanced Analytics for Boosting Date Production. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, K.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, K.; Chu, P.; Li, Z.; Lu, R. Development and evaluation of a dual-arm robotic apple harvesting system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Ahmed, S.; Reza, M.N.; Lee, K.-H.; Jin, H.; Ali, M.; Chung, S.-O.; Sung, J. A review on stereo vision for feature characterization of upland crops and orchard fruit trees. Precis. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 6, 104–122. [Google Scholar]

- Rayamajhi, A.; Jahanifar, H.; Asif, M.; Mahmud, M.S. Measuring Ornamental 3D Canopy Volume and Trunk Diameter Using Stereo Vision for Precision Spraying and Assessing Tree Maturity. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, 28–31 July 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, M.; Belwal, T. Advances in Postharvest and Analytical Technology of Horticulture Crops; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, B.L.; Tekeste, M.Z.; Gai, J.; Tang, L. Modeling, Simulation, and Visualization of Agricultural and Field Robotic Systems. In Fundamentals of Agricultural and Field Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D. Recognition and positioning of strawberries based on improved YOLOv7 and RGB-D sensing. Agriculture 2024, 14, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Xiong, Y.; From, P.J. Three-dimensional location methods for the vision system of strawberry-harvesting robots: Development and comparison. Prec. Agric. 2023, 24, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, V.M.; Boyd, N.S.; Peres, N.; Desaeger, J.; Lahiri, S.; Agehara, S. Chapter 16. Strawberry Production; HS736; University of Florida, IFAS Extension: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2023; Available online: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CV134 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- He, L.-h.; Zhou, Y.-z.; Liu, L.; Cao, W.; Ma, J.-H. Research on object detection and recognition in remote sensing images based on YOLOv11. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Ruan, S.; Tao, Y.; Rui, Y.; Deng, J.; Liao, P.; Mei, P. Improved YOLO algorithm based on multi-scale object detection in haze weather scenarios. CHAIN 2025, 2, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Huang, H.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; He, R. Rmt: Retentive networks meet vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 5641–5651. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, B.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Dai, Y.; Qin, F.; Peng, Y. Accurate leukocyte detection based on deformable-DETR and multi-level feature fusion for aiding diagnosis of blood diseases. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 107917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 6027–6037. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, P.; Yan, L.; Wan, J.; Sun, Y.; Tansey, K.; Asundi, A.; Zhao, H. Automatic checkerboard detection for camera calibration using self-correlation. J. Electron. Imaging 2018, 27, 033014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez-Salazar, R.; Zheng, J.; Diaz-Ramirez, V.H. Distorted pinhole camera modeling and calibration. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 11310–11318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culjak, I.; Abram, D.; Pribanic, T.; Dzapo, H.; Cifrek, M. A brief introduction to OpenCV. In Proceedings of the 2012 Proceedings of the 35th International Convention MIPRO, Opatija, Croatia, 21–25 May 2012; pp. 1725–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Gilat, A. MATLAB: An Introduction with Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Model | (Mean ± std) | (Mean ± std) | (Mean ± std) | (M) | (G) | (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11n | 0.876 ± 0.002 | 0.864 ± 0.001 | 0.926 ± 0.003 | 2.58 | 6.3 | 5.2 |

| YOLOv11s | 0.882 ± 0.003 | 0.874 ± 0.004 | 0.931 ± 0.002 | 9.41 | 21.3 | 18.3 |

| YOLOv11m | 0.874 ± 0.002 | 0.872 ± 0.002 | 0.936 ± 0.002 | 20.03 | 67.7 | 38.6 |

| YOLOv11l | 0.881 ± 0.001 | 0.873 ± 0.002 | 0.931 ± 0.003 | 25.28 | 86.6 | 48.8 |

| YOLOv11x | 0.885 ± 0.002 | 0.878 ± 0.001 | 0.934 ± 0.002 | 56.83 | 194.4 | 109.1 |

| yolov11n | CRA | HSFPN | Dysample | (Mean ± std) | (Mean ± std) | (Mean ± std) | (M) | (G) | (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| √ | 0.876 ± 0.002 | 0.864 ± 0.003 | 0.926 ± 0.002 | 2.58 | 6.3 | 5.2 | |||

| √ | √ | 0.889 ± 0.001 | 0.852 ± 0.002 | 0.928 ± 0.002 | 2.47 | 6.1 | 5.0 | ||

| √ | √ | 0.871 ± 0.003 | 0.899 ± 0.002 | 0.931 ± 0.003 | 2.07 | 7.0 | 4.2 | ||

| √ | √ | 0.888 ± 0.002 | 0.877 ± 0.001 | 0.924 ± 0.004 | 2.45 | 5.9 | 4.8 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 0.882 ± 0.003 | 0.869 ± 0.004 | 0.933 ± 0.003 | 1.95 | 7.2 | 4.0 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 0.907 ± 0.002 | 0.871 ± 0.003 | 0.935 ± 0.001 | 2.49 | 6.2 | 5.0 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 0.901 ± 0.004 | 0.869 ± 0.003 | 0.937 ± 0.002 | 1.75 | 5.0 | 3.6 | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.918 ± 0.001 | 0.902 ± 0.002 | 0.946 ± 0.002 | 1.63 | 4.8 | 3.4 |

| Model | (Mean ± std) | (Mean ± std) | (Mean ± std) | (M) | (G) | (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOOD | 0.917 ± 0.002 | 0.897 ± 0.002 | 0.945 ± 0.003 | 32.02 | 167.7 | 244.0 |

| SSD | 0.875 ± 0.002 | 0.884 ± 0.001 | 0.931 ± 0.004 | 24.01 | 30.53 | 184.0 |

| YOLOv5n | 0.9085 ± 0.003 | 0.858 ± 0.003 | 0.936 ± 0.001 | 2.50 | 7.1 | 5.0 |

| YOLOv6n | 0.8751 ± 0.001 | 0.894 ± 0.003 | 0.937 ± 0.002 | 4.23 | 11.8 | 8.3 |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 0.875 ± 0.004 | 0.881 ± 0.002 | 0.922 ± 0.002 | 6.01 | 13.0 | 11.6 |

| YOLOv7 | 0.901 ± 0.003 | 0.892 ± 0.004 | 0.944 ± 0.003 | 36.49 | 103.2 | 71.3 |

| YOLOv8n | 0.8997 ± 0.002 | 0.871 ± 0.002 | 0.931 ± 0.003 | 3.01 | 8.1 | 6.0 |

| YOLOv8s | 0.8759 ± 0.003 | 0.898 ± 0.001 | 0.937 ± 0.002 | 11.12 | 28.4 | 21.5 |

| YOLOv9c | 0.8657 ± 0.002 | 0.893 ± 0.004 | 0.933 ± 0.003 | 25.32 | 102.3 | 49.2 |

| YOLOv10n | 0.8788 ± 0.001 | 0.869 ± 0.003 | 0.922 ± 0.003 | 2.27 | 6.5 | 5.5 |

| RTDETR-l | 0.8375 ± 0.001 | 0.802 ± 0.002 | 0.889 ± 0.002 | 31.98 | 103.4 | 63.1 |

| RAFS-YOLO | 0.918 ± 0.001 | 0.902 ± 0.002 | 0.946 ± 0.002 | 1.63 | 4.8 | 3.4 |

| Parameter | RGB Camera |

|---|---|

| Internal Parameter Matrix | |

| Radial Distortion Coefficients | |

| Tangential Distortion Coefficients |

| Distance Interval (cm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–40 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.15 |

| 40–50 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.3 |

| 50–60 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, K.; Wei, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W. Research on Strawberry Visual Recognition and 3D Localization Based on Lightweight RAFS-YOLO and RGB-D Camera. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212212

Li K, Wei X, Wang Q, Zhang W. Research on Strawberry Visual Recognition and 3D Localization Based on Lightweight RAFS-YOLO and RGB-D Camera. Agriculture. 2025; 15(21):2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212212

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Kaixuan, Xinyuan Wei, Qiang Wang, and Wuping Zhang. 2025. "Research on Strawberry Visual Recognition and 3D Localization Based on Lightweight RAFS-YOLO and RGB-D Camera" Agriculture 15, no. 21: 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212212

APA StyleLi, K., Wei, X., Wang, Q., & Zhang, W. (2025). Research on Strawberry Visual Recognition and 3D Localization Based on Lightweight RAFS-YOLO and RGB-D Camera. Agriculture, 15(21), 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212212