Territorial Disparities, Structural Imbalances and Economic Implications in the Potato Crop System in Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- normality of residual distribution (the difference between observed and estimated values) was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test and graphical analysis (histogram of standardized residuals and Q–Q plot),

- -

- autocorrelation of residuals was tested using the Durbin–Watson statistic,

- -

- heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance of residuals) was examined using the Breusch–Pagan test and visual inspection of residual plots, which can reveal irregular patterns such as variable dispersion, trends, or non-linear relationships,

- -

- multicollinearity was assessed through the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), maintaining values below the threshold of 5, in accordance with econometric recommendations,

- -

- the R2 and adjusted R2 coefficients were determined to evaluate the degree of variation explained by the model, respectively, the quality of adjustment of simple linear models;

- -

- checking the overall significance of the regression (through F-test) and the individual significance (through the p-values of the coefficients).

- Pi = total potato production value (tons),

- Ai = cultivated area (hectares),

- Yi = average yield (kg/ha),

- Pri = average price per kilogram (€/kg),

- εi = random error term.

3. Results

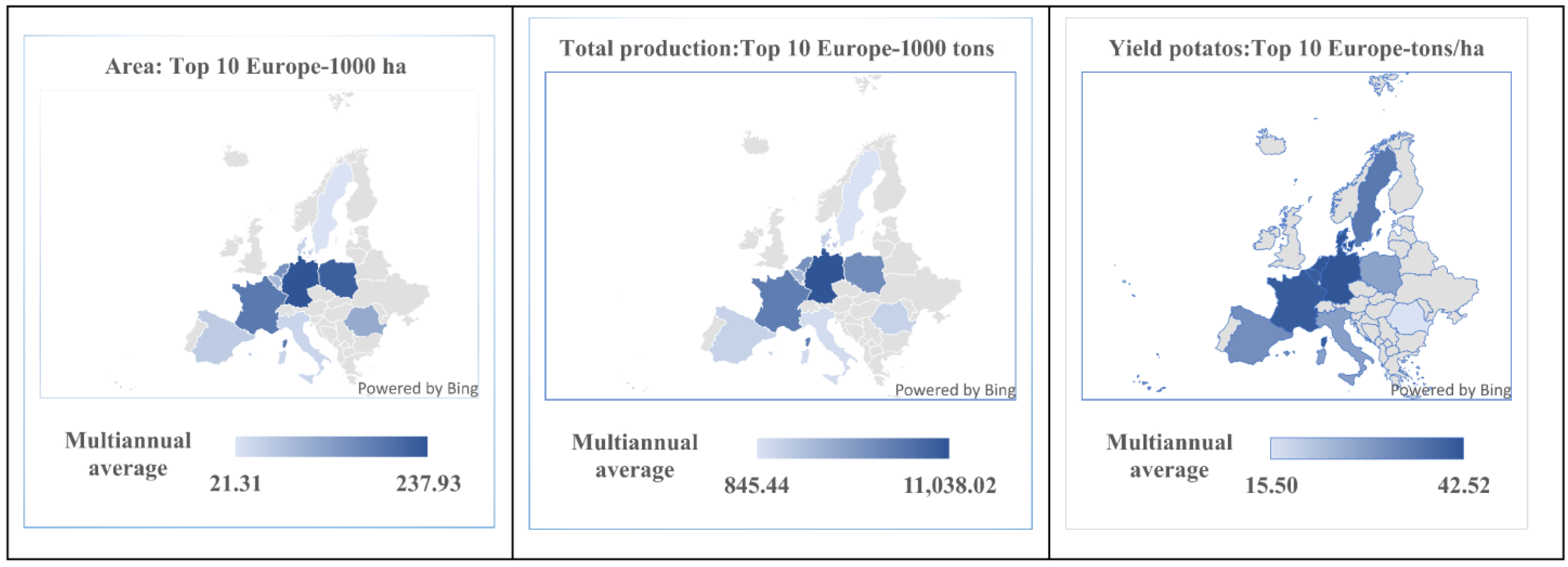

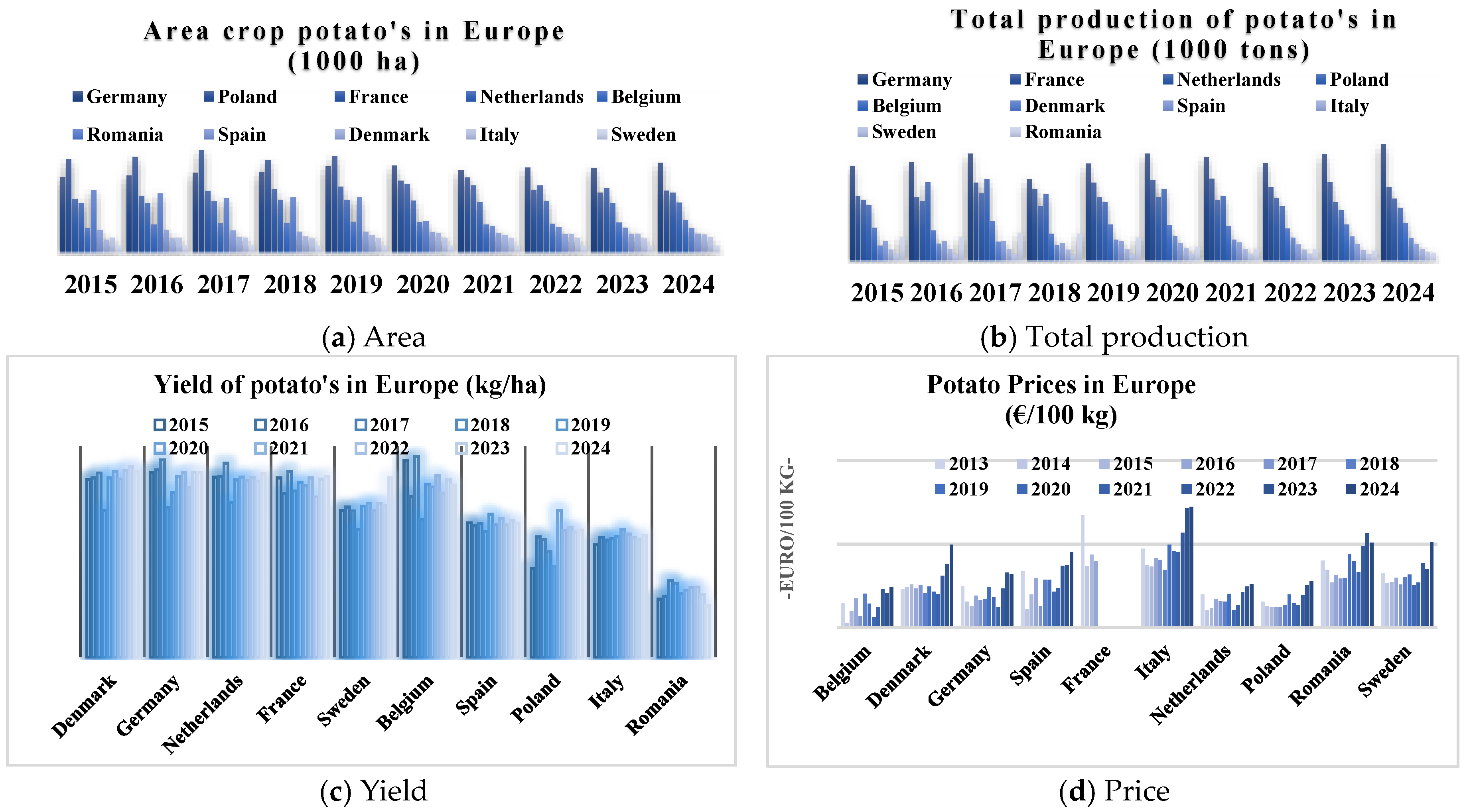

3.1. Results for the Analysis of the Potato Crop System in Europe

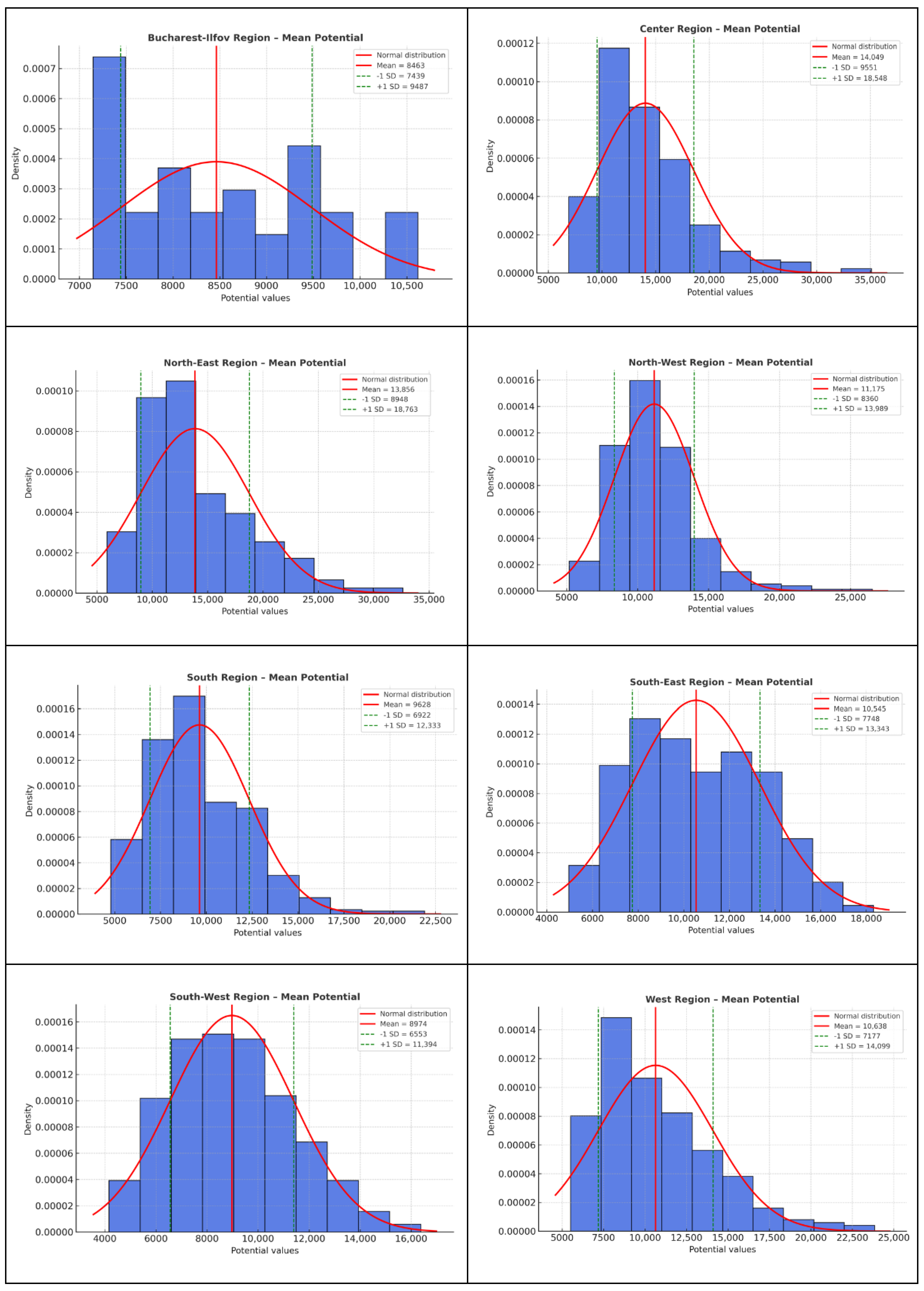

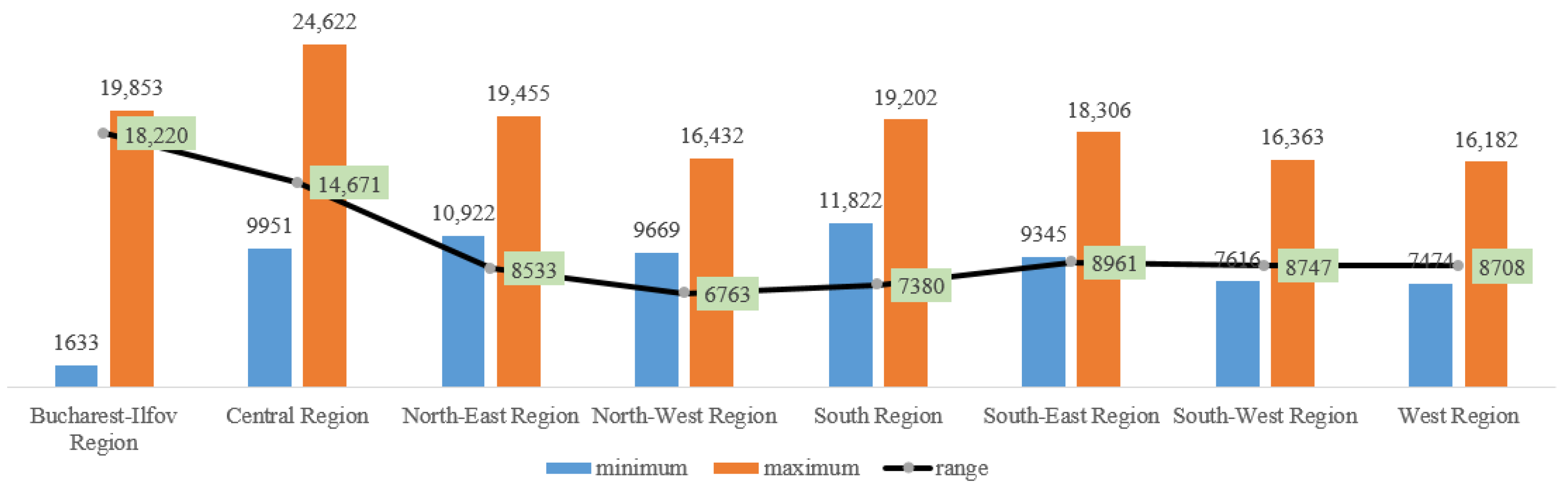

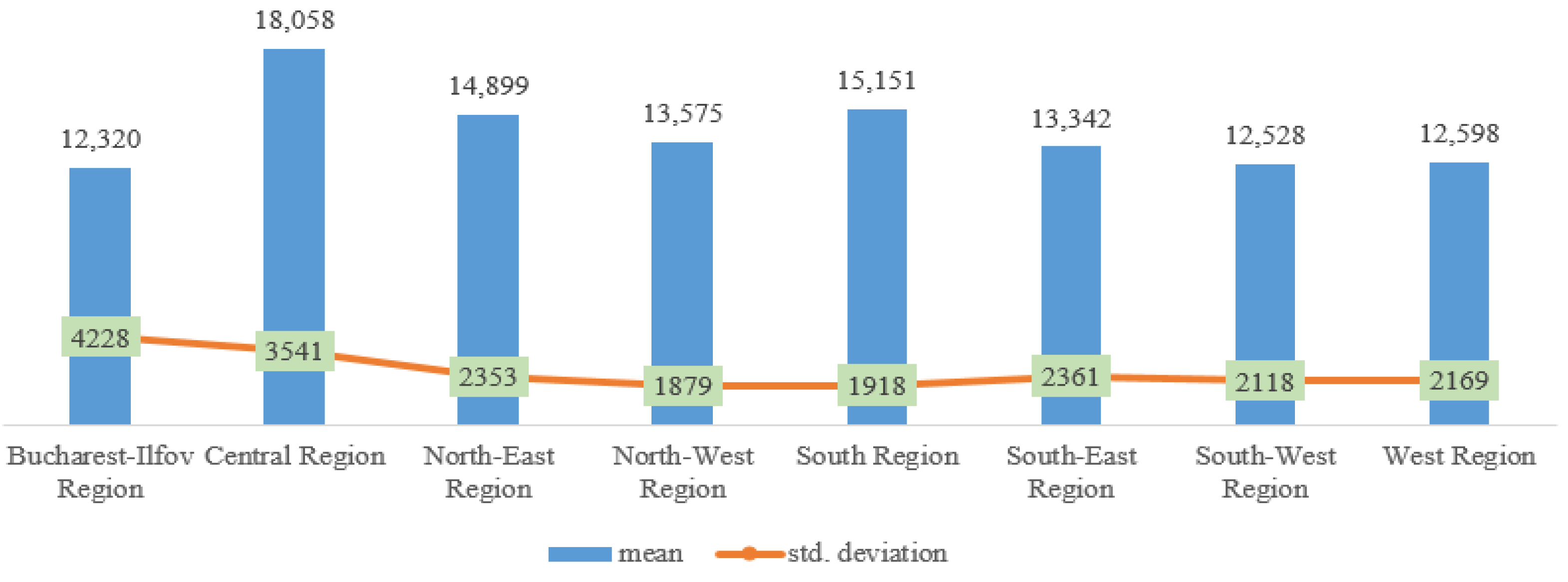

3.2. Results for Romania

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Statistical Results Determined by the Area-Production Relationship

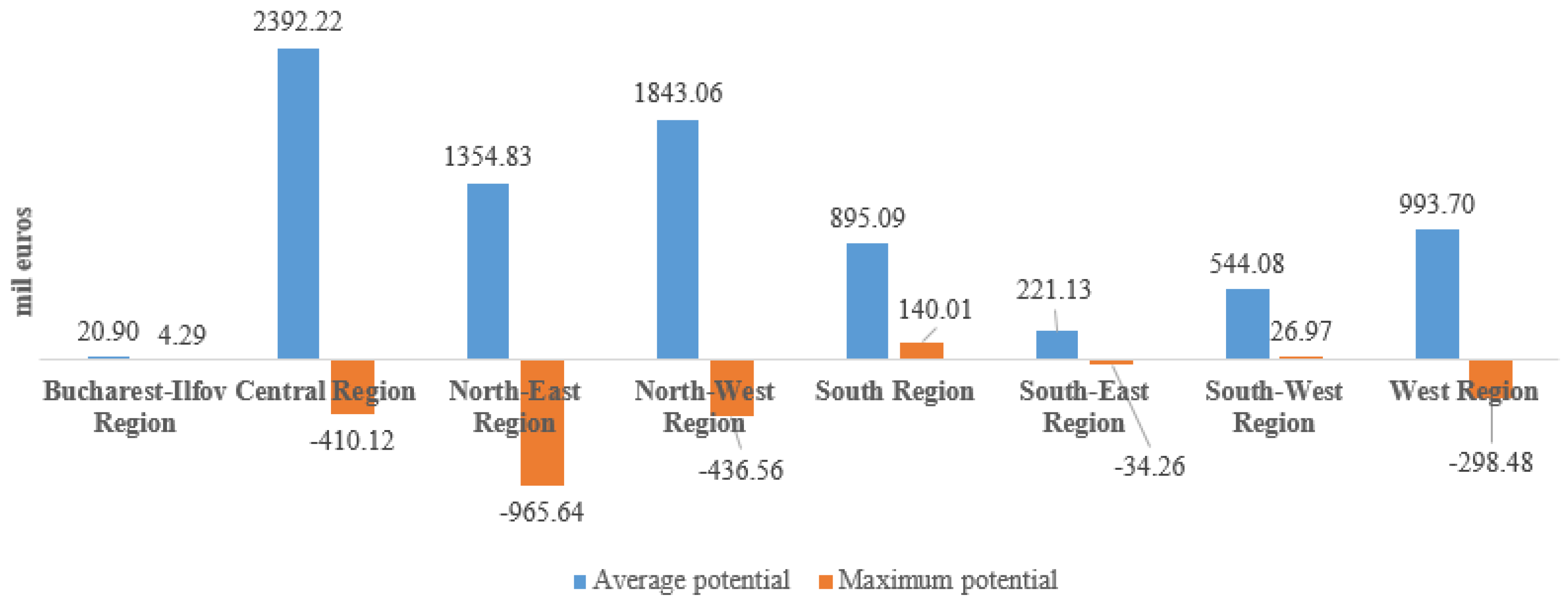

4.2. Discussions About Regional Disparities and Economic Implications

4.3. Indicative Estimation of Average Costs per Hectare and Implications for Profit Margins

4.4. Link to Previous Studies and Policy Recommendations

4.5. Recommendations for Highlighting the Economic Benefits of Potatoes

- Bucharest-Ilfov Region: Given its limited representativeness for potato cultivation, it is recommended that potatoes be excluded from the zonal crop plan. Instead, investments should target niche technologies such as urban agriculture and vertical farming, which better align with the region’s agricultural profile;

- Central Region: This region records the highest maximum potential, warranting the establishment of pilot projects or centers of excellence for potato production. Increased support for farmers through training programs and digitalization initiatives is also recommended to reduce intra-regional variability;

- North-East Region: Continued support programs for small and medium-sized farms are advisable, focusing on the promotion of locally adapted varieties and the expansion of storage and processing capacities to strengthen the value chain;

- North-West Region: Efforts should concentrate on modernizing irrigation and mechanization systems, supporting the creation of agricultural cooperatives, and strengthening local and regional markets through the development of short supply chains;

- South Region: With its stable yields and strong production performance, this region should be prioritized for the expansion of potato cultivation and for vertical integration with local processing industries;

- South-East Region: Characterized by higher yield variability, this region requires targeted investments in anti-drought systems and agricultural infrastructure. Farmer training in risk management and the development of financial instruments to mitigate climate-related risks should also be key policy components;

- South-West Region: As one of the most stable agricultural regions, the South-West should promote sustainable farming practices and optimize regional logistics chains to improve competitiveness;

- The Western Region: Although stable, this region’s relatively low maximum potential suggests the need to enhance productivity through the introduction of higher-yielding potato varieties and improved cultivation techniques.

4.6. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.P.; Kromann, P.; Andrade-Piedra, J.; Polar, V.; Hareau, G. The Potato of the Future: Opportunities and Challenges in Sustainable Agri-food Systems. Potato Res. 2021, 64, 681–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Naz, S.; Ahmed, M.; Abbas, G.; Fatima, Z.; Hussain, S.; Iqbal, P.; Ghani, A.; Ali, M.; Awan, T.H.; Samad, N.; et al. Assessment of Climate Change Impact on Potato-Potato Cropping System Under Semi-arid Environment and Designing of Adaptation Strategies. Potato Res. 2025, 68, 1209–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Fudjoe, S.K.; Palta, J.A.; Li, L.; Li, S. Effects of Irrigation Practices on Potato Yield and Water Productivity: A Global Meta-Analysis. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkort, A.J.; Struik, P.C. Yield levels of potato crops: Recent achievements and future prospects. Field Crops Res. 2015, 182, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokbergenova, Z.; Aitbayev, T.; Sharipova, D.; Jantassova, A.; Makhanova, G.; Ibraiymova, M.; Konysbayeva, H. Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) healthy planting material development through innovative methods. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2025, 57, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, B.; Jayanta, D.; Nandi, A. A Study on the Variability in Market Arrivals and Prices of Potato in Some Selected Markets of West Bengal. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 9, 4621–4625. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, K.; Akhtar, M.H. Potato Production, Usage, and Nutrition—A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, M.; Liu, G.; Tian, S.; Zeng, F. The Global Potato-Processing Industry: A Review of Production, Products, Quality and Sustainability. Foods 2025, 14, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogita, R.J.; Prajapati, C.S.; Roy, S.; Abrol, P.; Khan Chand, A.K.; Darbha, S. Extension strategies to promote post-harvest management and value addition: A review. Horticulture 2024, 50, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.J.; George, T.S. Feeding nine billion: The challenge to sustainable crop production. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5233–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, M.K.; Baishya, P.; Ramteke, A.; Farooq, M.; Baroowa, B.; Sunkar, R.; Gogoi, N. Effect of high temperature on yield associated parameters and vascular bundle development in five potato cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaman, K.; Irmak, S.; Koudahe, K.; Allen, S. Irrigation Management in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Production: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, O.I.M.; Ortiz, W.A.W.; Diaz, R.E.V.; Malagón, E.M.E. Rotation as a strategy to increase the sustainability of potato crop. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2024, 54, e77804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.M.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.Z.; Zhou, Z.-J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Zhu, J.-H.; Liu, Y.-H.; Zhang, L.-F. Crop rotations increased soil ecosystem multifunctionality by improving keystone taxa and soil properties in potatoes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1034761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, D.; Lin, T.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, L.; Jiao, X. Effects of rotation corn on potato yield, quality, and soil microbial communities. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1493333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, L.; Li, C.; Xie, S.; Niu, Q. Potato Planter and Planting Technology: A Review of Recent Developments. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekesa, T.; Jaquet, S.; Calles, T.; Katsir, S.; Vollmann Tinoco, V. (2024) Fields of Harmony: Pulses and Sustainable Land Management. 26p. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/139357 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Sumner, D.R. Crop rotation and plant productivity. In Handbook of Agricultural Productivity. Volume I: Plant Productivity; Rechcigl, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 273–314. ISBN 9781351072878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoicea, P.; Dușa, E.M.; Toma, E. Implementing Environmental Policies on Farms in Romania; Total Publishing: Bucharest, Romania, 2023; ISBN 978-606-9643-60-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stoicea, P.; Basa, A.G.; Stoian, E.; Toma, E.; Micu, M.M.; Gidea, M.; Dobre, C.; Iorga, A.; Chiurciu, I. Crop Rotation Practiced by Romanian Crop Farms before the Introduction of the “Environmentally Beneficial Practices Applicable to Arable Land” Eco-Scheme. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Cassman, K.G.; Field, C.B. Crop yield gaps: Their importance, magnitudes, and causes. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ittersum, M.K.; Cassman, K.G.; Grassini, P.; Wolf, J.; Tittonell, P.; Hochman, Z. Yield gap analysis with local to global relevance—A review. Field Crops Res. 2013, 143, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassman, K.G. Ecological intensification of cereal production systems: Yield potential, soil quality, and precision agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5952–5959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schils, R.; Olesen, J.E.; Kersebaum, K.C.; Rijk, B.; Oberforster, M.; Kalyada, V.; van Ittersum, M.K. Cereal yield gaps across Europe. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 101, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Churkina, G.; Gessler, A.; Wieland, R.; Bellocchi, G. Yield gap of winter wheat in Europe and sensitivity of potential yield to climate factors. Clim. Res. 2016, 67, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- van Loon, M.P.; Alimagham, S.; Abuley, I.K.; Boogaard, H.; Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; de Galarreta, J.I.R.; Geling, E.H.; Kryvobok, O.; Kryvoshein, O.; Landeras, G.; et al. Insights into the potential of potato production across Europe. Crop Environ. 2025, 4, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yield Gap Atlas–Europe. (n.d.). Global Yield Gap Atlas. Available online: https://www.yieldgap.org/europe (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- West, P.; Gerber, J.; Cassidy, E.S.; Stiffman, S. Only half of the calories produced on croplands are available for human consumption. Environ. Res. Food Syst. 2025, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Potato Center (CIP). 2025. Available online: https://cipotato.org/potato/potato-facts-and-figures/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Wengle, S.A.; Musabaeva, S.; Greenwood-Sánchez, D. Second Bread: Potato Crop and Food Security in Kyrgyzstan. J. Dev. Stud. 2024, 60, 1691–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union of the Potato Trade, Europatat. Available online: https://europatat.eu/activities/the-eu-potato-sector/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Kandel, P.; Khanal, Y.R.; Poudel, N.; Magrati, B.; Dhakal, N. Comprehensive economic evaluation of potato farming in Baglung, Nepal: Productivity, profitability, and resource use efficiency. Econ. Growth Environ. Sustain. 2024, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.H.; Ei, E.; Kuk, Y.I. Effects of Climate Variation on Spring Potato Growth, Yield, and Quality in South Korea. Agronomy 2025, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burja, V. Regional Disparities of Agricultural Performance in Romania. Ann. Univ. Apulensis Ser. Oeconomica 2011, 1, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dona, I.; Dumitru, R. Effects generated by the accession to the European Union in the field of trading cereal products. Sci. Pap. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2012, 12, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. The EU Potato Sector-Statistics on Production, Prices and Trade. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=The_EU_potato_sector_-_statistics_on_production,_prices_and_trade (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics. Area, Production and Average Annual Consumption. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- National Research and Development Institute for Pedology, Agrochemistry and Environmental Protection, ICPA Bucharest. Available online: https://icpa.ro/info-fermieri/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Isaic-Maniu, A.L.; Mitrut, C.; Voineagu, V. Statistics; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Voineagu, V.; Ţiţan, E.; Ghiţă, S.; Boboc, C.; Todose, D. Statistics—Theoretical Foundations and Applications; Economic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Bank of Romania. Available online: https://www.bnr.ro (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Mueller, N.D.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Ray, D.K.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Closing yield gaps: Nutrient and water management to boost crop production. Nature 2012, 490, 254–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pushpalatha, R.; Gangadharan, B. Climate resilience, yield and geographical suitability of sweet potato under the changing climate: A review. Nat. Res. Forum 2024, 48, 106–119. [Google Scholar]

- Seno Nascimento, C.; Seno Nascimento, C.; de Jesus Pereira, B.; Soares Silva, P.H.; Pessôa da Cruz, M.C.; Bernardes Cecílio Filho, A. Enhancing Sustainability in Potato Crop Production: Mitigating Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Nitrate Accumulation in Potato Tubers through Optimized Nitrogen Fertilization. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrar, T.M.C.; Brașovean, I.; Racz, C.-P.; Mîrza, C.M.; Burduhos, P.D.; Mălinaș, C.; Moldovan, B.M.; Odagiu, A.C.M. The Impact of Agricultural Inputs and Environmental Factors on Potato Yields and Traits. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, S.; Lievens, J.; de Vries, A. Potato production in Northwestern Europe: Characteristics, issues, and challenges. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEP–Institute for European Environmental Policy. Increasing Climate Resilience: Growing Potatoes Using Regenerative Agriculture. 2024. Available online: https://ieep.eu (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development/MADR. PS PAC 2023–2027/CAP Strategic Plan 2023-2027 for Romania, Version 7.1 of 02.12.2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.madr.ro/docs/dezvoltare-rurala/plan-national-strategic/2024/PS-PAC-2023-2027-v7.1-aprobata.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Zarzyńska, K.; Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; Nosalewicz, A. Differences in size and architecture of the potato cultivars root system and their tolerance to drought stress. Plant Soil Environ. 2017, 63, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimullin, M.; Abdrakhmanov, R.; Andreev, R.; Semenov, A.; Vasilyev, O.; Zaitsev, P.; Arkhipov, S. Improvement of potato crop technology. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Macau, 21–23 July 2019; Volume 346, p. 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, M.; Johnstone, N.; Mweu, C.; Mehari, T. Potato Production in Eritrea: Status, Challenges and Prospects. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2024, 11, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Mulching improves yield and water-use efficiency of potato cropping in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ştefan, F.M.; Chiru, S.C.; Iliev, P.; Ilieva, I.; Zhevora, S.V.; Oves, E.V.; Polgar, Z.; Balogh, S. Chapter 21—Potato production in Eastern Europe (Romania, Republic of Moldova, Russia and Hungary). In Potato Production Worldwide; Caliskan, M.E., Bakhsh, A., Jabran, K., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 381–395. ISBN 978-0-12-822925-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hoza, G.; Dinu, M.; Becherescu, A.D.; Neagu, M. Research regarding the influence of tuber size and protection systems on the early potato production. AgroLife Sci. J. 2017, 6, 120–126. Available online: https://agrolifejournal.usamv.ro/index.php/agrolife/article/view/193/193 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Mack, G.; Fîntîneru, G.; Kohler, A. Do rural development measures improve vitality of rural areas in Romania? AgroLife Sci. J. 2018, 7, 82–98. Available online: https://www.agrolifejournal.usamv.ro/index.php/agrolife/article/view/231 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Micu, M.M.; Dinu, T.A.; Fintineru, G.; Tudor, V.C.; Stoian, E.; Dumitru, E.A.; Stoicea, P.; Iorga, A. Climate Change—Between “Myth and Truth” in Romanian Farmers’ Perception. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification | N | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average potential—potato | 2687 | 30,963.6 | 4158.8 | 35,122.4 | 11,159.6 |

| Maximum potential—potato | 2687 | 42,556.6 | 5423.8 | 47,980.4 | 15,281.9 |

| Region | Average Potential (kg/ha) | Share of Mean Yield in Average Potential (%) | Share of Maximum Yield in Average Potential (%) | Maximum Potential (kg/ha) | Share of Mean Yield in Maximum Potential (%) | Share of Maximum Yield in Maximum Potential (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucharest-Ilfov Region | 5162.3 | 238.7 | 384.6 | 11,763.6 | 104.7 | 168.8 |

| Central Region | 9229.7 | 195.7 | 266.8 | 18,869.0 | 95.7 | 130.5 |

| North-East Region | 9435.7 | 157.9 | 206.2 | 18,275.3 | 81.5 | 106.5 |

| North-West Region | 6616.4 | 205.2 | 248.4 | 15,733.0 | 86.3 | 104.4 |

| South Region | 5798.6 | 261.3 | 331.1 | 13,456.4 | 112.6 | 142.7 |

| South-East Region | 7010.9 | 190.3 | 261.1 | 14,079.4 | 94.8 | 130.0 |

| South-West Region | 5616.6 | 223.1 | 291.3 | 12,330.6 | 101.6 | 132.7 |

| West Region | 5820.9 | 216.4 | 278.0 | 15,455.2 | 81.5 | 104.7 |

| Region | Regression Equation (Y = β0 + β1X) | Std. Error | p-Value | R2 | Adj. R2 | F-Statistic (p) | Durbin–Watson | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North-East | Y = 13.485 + 0.021X | 0.012 | 0.084 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 2.67 | 1.96 | 1.03 |

| South-East | Y = 12.933 + 0.047X | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 7.41 | 2.11 | 1.08 |

| South | Y = 13.210 + 0.042X | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 6.22 | 2.05 | 1.06 |

| South-West | Y = 12.867 + 0.028X | 0.014 | 0.065 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 3.89 | 1.84 | 1.02 |

| West | Y = 13.744 + 0.019X | 0.013 | 0.114 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.97 | 2.07 | 1.05 |

| North-West | Y = 13.602 + 0.025X | 0.014 | 0.076 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 2.93 | 1.93 | 1.02 |

| Central | Y = 13.155 + 0.036X | 0.015 | 0.049 | 0.22 | 0.2 | 5.11 | 2.14 | 1.07 |

| Bucharest–Ilfov | Y = 13.882 + 0.017X | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 1.55 | 2.08 | 1.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoicea, P.; Chiurciu, I.-A.; Cofas, E. Territorial Disparities, Structural Imbalances and Economic Implications in the Potato Crop System in Romania. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222343

Stoicea P, Chiurciu I-A, Cofas E. Territorial Disparities, Structural Imbalances and Economic Implications in the Potato Crop System in Romania. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222343

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoicea, Paula, Irina-Adriana Chiurciu, and Elena Cofas. 2025. "Territorial Disparities, Structural Imbalances and Economic Implications in the Potato Crop System in Romania" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222343

APA StyleStoicea, P., Chiurciu, I.-A., & Cofas, E. (2025). Territorial Disparities, Structural Imbalances and Economic Implications in the Potato Crop System in Romania. Agriculture, 15(22), 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222343