Consumer Perceptions of Greenwashing in Local Agri-Food Systems and Rural Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comprehensive, Multi-Dimensional Literature Analysis of Greenwashing Concept and Its Discourses

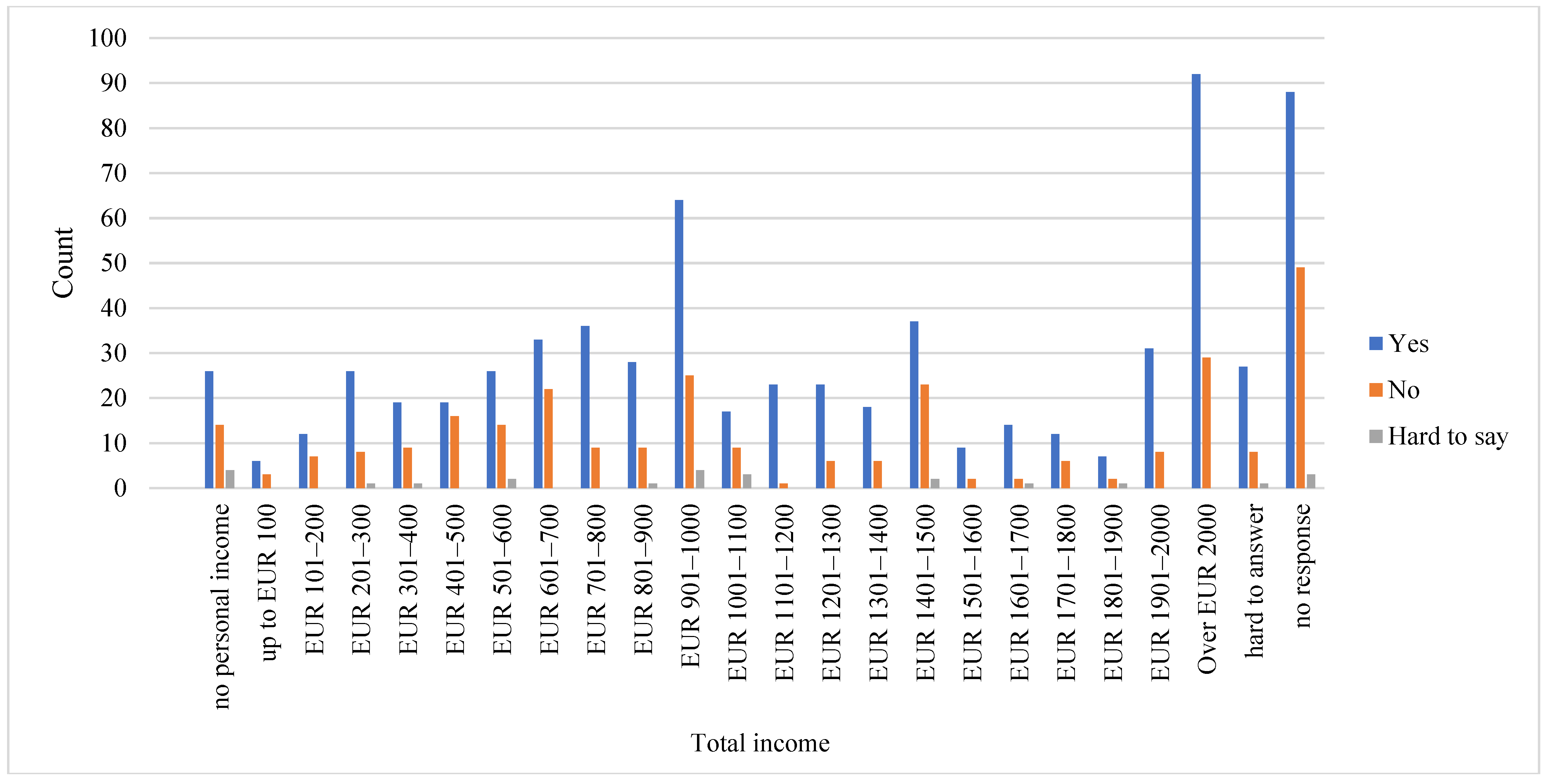

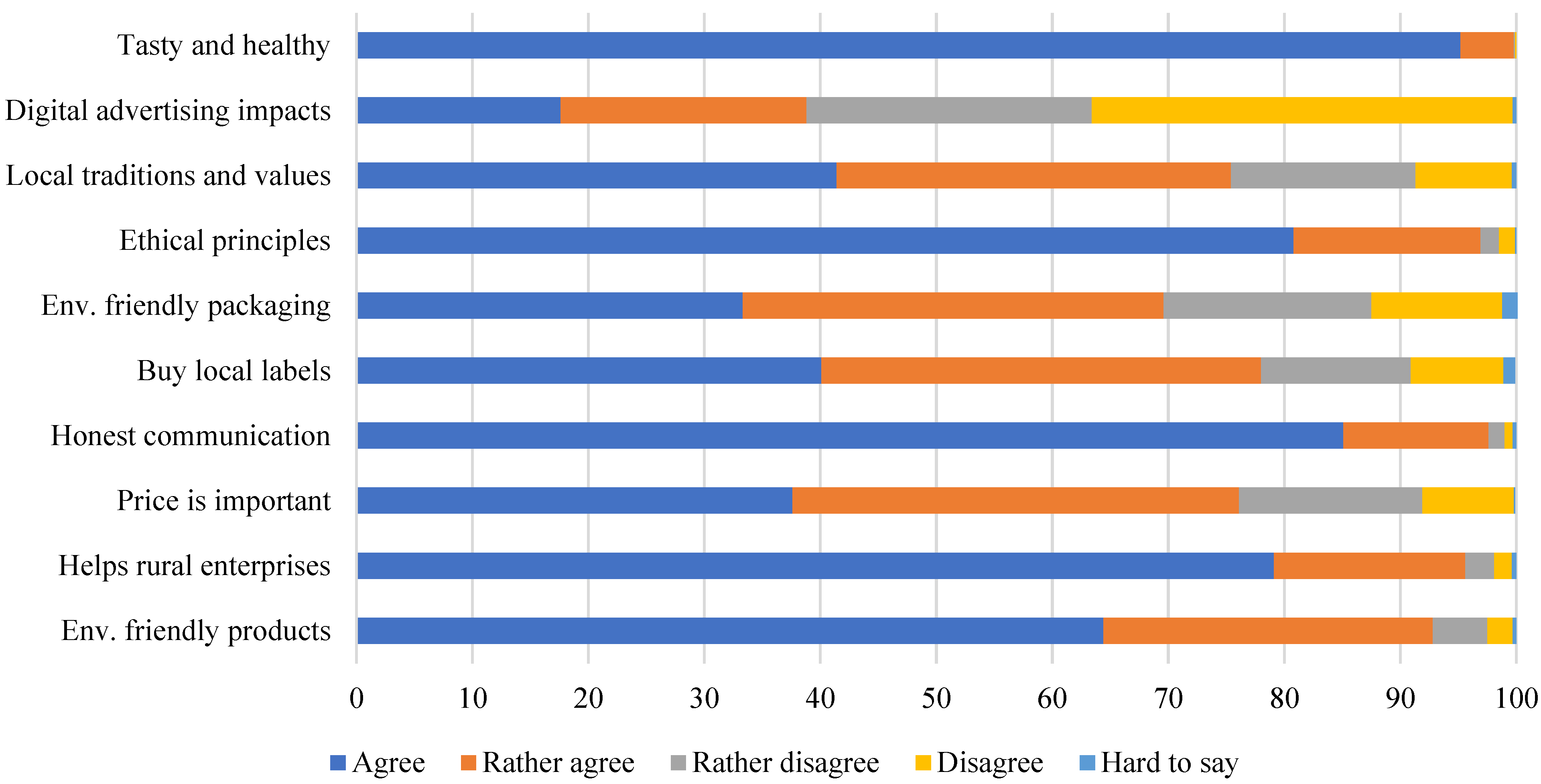

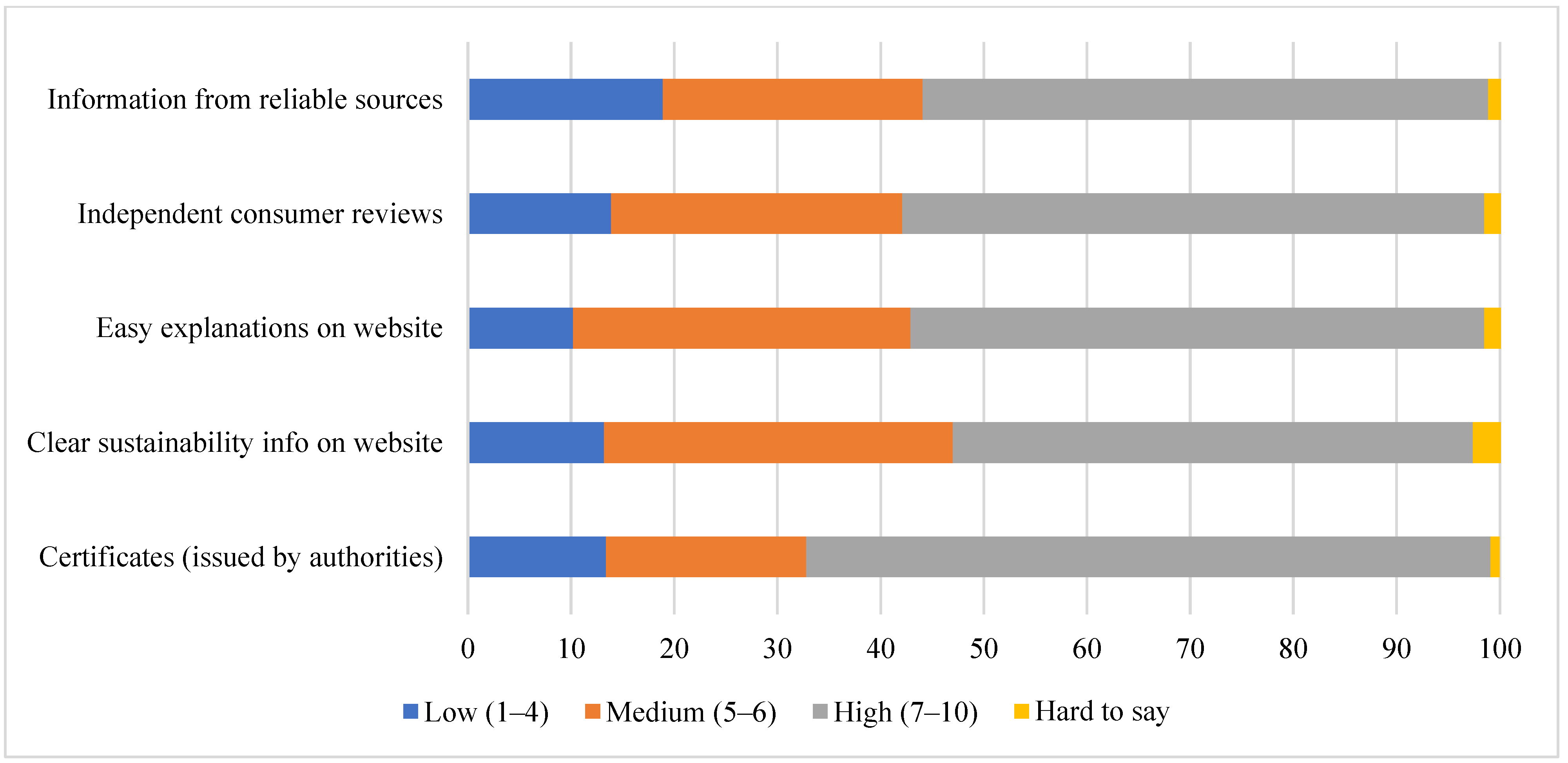

3.2. Survey of Latvian Consumer Views on Greenwashing in the Rural Business Sector

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aleksiev, G.; Zheleva, V. European Climate Policy Impact on Rural Tourism in Bulgaria. Uluslararası Ekon. Siyaset İnsan Ve Toplum Bilim. Derg. 2025, 8, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network for Rural Development. EU Rural Review No. 31: Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://ruralization.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/eu-rural-review.-long-term-vision-for-rural-areas-2.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Geng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Gao, J. Bibliometric analysis of sustainable rural tourism. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. How can rural tourism be sustainable? A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.T.H.; Hoang, H.H.; Hoang, T.N.N.; Nguyen, X.L. Bibliometric and content analysis of global trends in digital transformation and rural tourism. Geoj. Tourism Geosites 2025, 58, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakhubia, N.; Gogitidze, G.; Shainidze, J.; Lazishvili, S.; Goguadze, L. Advancing Rural Tourism in Adjara: Key Projects and Strategic Approaches. Eur. Sci. J. 2025, 21, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroismayr, S.; Tuitjer, G.; Machold, I.; Mahon, M. Arts and Culture for a Sustainable Future in Rural Areas. Eur. Countrys. 2025, 17, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramly, Z.T.; Ishak, M.Y.; Abdullah, A.M.; Ismail, M.; Abdullah, S.; Mansor, A.A. Investigating the Effectiveness of Coal-Fired Power Plant Operations: Management, Technical and Air Pollution Aspects. Emerg. Sci. J. 2025, 9, 86–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, L.P.; Tam, P.T. Managerial recommendations for enhancing green consumption behavior and sustainable consumption. Emerg. Sci. J. 2024, 8, 2245–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Sheng, T.; Zhou, X.; Shen, C.; Fang, B. How Does Young Consumers’ Greenwashing Perception Impact Their Green Purchase Intention in the Fast Fashion Industry? An Analysis from the Perspective of Perceived Risk Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Nogueira, S. Willingness to pay more for green products: A critical challenge for Gen Z. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Latvia. Latvia’s CAP Strategic Plan 2023–2027; Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Latvia: Riga, Latvia, 2022. Available online: https://www.zm.gov.lv/public/ck/files/ZM/Strategiskais%20plans/CAP_SP_Latvia_ENG.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Eurostat. Actual Individual Consumption per Capita and GDP per Capita. Eurostat Statistics Explained. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=GDP_per_capita,_consumption_per_capita_and_price_level_indice (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- OECD. Household Disposable Income (Indicator). OECD Data. 2023. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-disposable-income.htm (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; Gonzalez-Portillo, A. Disentangling the relationship between rurality and tourism from a peripheral rural area of Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 115, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy. Tourism and Rural Development: Delivering for the Regions (QG-05-23-426-EN-N); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://case-research.eu/app/uploads/2024/06/QG0523426ENN20Tourism20and20rural20development.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- World Law Group. Greenwashing vs. Corporate Responsibility. 2023. The World Law Group. Available online: https://www.theworldlawgroup.com/membership/news/news-greenwashing-vs-corporate-responsibility (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Najem, R.; Metcalfe, B.D. Greenwashing in the era of sustainability: A systematic literature review. Corp. Gov. Sustain. Rev. 2025, 9, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.; Nemes, N.; Montgomery, A.W.; Scanlan, S.; McNally, B.; Tubiello, F.; Aronczyk, M.; Wood, T.; Smith, T.; Kaupa, C. Testing the greenwashing assessment framework. Ecol. Soc. 2025, 30, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. A Multidimensional Analysis of Language Use in English Argumentative Essays: An Evidence from Comparable Corpora. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231197088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, M. Reviewing literature through multidimensional representations. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2023, 49, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihan, S.T. Karl Pearsons chi-square tests. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 15, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.; Rana, R. Chi-square test and its application in hypothesis testing. J. Pract. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2015, 1, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishan, K.; Azhar, Z. Greenwashing in sustainability reporting: Evidence from Malaysia. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguila, C.I.G.; Arellano, M.P.C.D.; Vega, M.A.R.; Mondragón, E.M.B.; Castro, M.P.Q.D.; Castro, G.A.Q. Trends in scientific production on greenwashing based on Scopus (1990–2023). Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublóy, Á.; Keresztúri, J.L.; Berlinger, E. Quantifying firm-level greenwashing: A systematic literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakuwanika, M.; Panicker, M. The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Yang, Z. Trends in Corporate Environmental Compliance Research: A Bibliometric Analysis (2004–2024). Sustainability 2024, 16, 5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Goel, S. Sustainability reporting and greenwashing: A bibliometrics assessment in G7 and non-G7 nations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2320812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Khan, S. Greenwashing: An Integrated Thematic and Content Analysis of Literature through Scientometrics Methods. Thail. World Econ. 2024, 42, 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Balaskas, S.; Stamatiou, I.; Komis, K.; Nikolopoulos, T. Perceptions of Greenwashing and Purchase Intentions: A Model of Gen Z Responses to ESG-Labeled Digital Advertising. Risks 2025, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Brand Advocacy among Consumers: The Mediating Role of Brand Trust. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fella, S.; Bausa, E. Green or greenwashed? Examining consumers’ ability to identify greenwashing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. Greenwashing prevention in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures: A bibliometric analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 74, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberga-Zalite, G.; Zvirbule, A. Analysis of waste minimization challenges to European food production enterprises. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Billon, P.; Lujala, P.; Rustad, S.A. Transparency in environmental and resource governance: Theories of change for the EITI. Glob. Environ. Politics 2021, 21, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Reinermann, J.-L.; Guillen Mandujano, G.; DesRoches, C.T.; Diddi, S.; Vergragt, P.J. Sustainable consumption communication: A review of an emerging field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 300, 126880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombinho, M.; Fialho, A.; Novas, J. Readability of Sustainability Reports: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popluga, D.; Grīnberga-Zālīte, G. How Ready Are Society for European Green Deal: Case Study from Latvia? Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConference SGEM 2022, 22, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghi, M. Report on the Future of European Competitiveness; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu (accessed on 19 August 2025).

| Theme/Focus Area | Description/Key Insights | Period of Analysis | Main Supporting Studies | Relevance to Rural Development and Local Food Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume and growth of publications | Approx. 355 publications with greenwashing in the title (1996–2021), with rapid growth post-2019. | 1996–2021 (peak post-2019) | [25,29] | Highlights the growing need to scrutinize “green” claims, including those from agri-businesses marketing rural or local food systems. |

| Focus on sustainability reporting | A total of 137 publications focus specifically on greenwashing in sustainability reporting. | 2003–2023 | [24] | Relevant for rural producers and cooperatives promoting sustainable practices; risk of greenwashing through misleading certifications. |

| Common keywords and themes | Frequently used keywords: sustainability, CSR, business ethics, environmental policy—showing a multidisciplinary research scope. | 1990–2023 | [25] | CSR and sustainability claims are central to rural branding and local food identity—important to guard against misuse. |

| Emerging research trends | Rapid increase in concern about misleading sustainability claims, especially among businesses. Consumers are seen as central in identifying and reacting to these claims. | Last 5 years | [23,29] | Consumers of local and rural food systems increasingly demand transparency and authenticity in sustainability claims. |

| Systematic reviews and theoretical models | Reviews develop integrated models that examine causes, impacts, and resistance to greenwashing across cultural and policy contexts. | Ongoing | [18] | Frameworks can inform policy and advocacy efforts targeting rural supply chains and agri-marketing ethics. |

| Consumer perception studies | Studies assess how well consumers detect greenwashing using surveys and experiments; results show detection improves when awareness is prompted. | Ongoing | [33] | Consumer awareness is crucial for rural/local markets where labels like “organic”, “natural”, or “farm-raised” may be misused. |

| Policy and governance focus | Research explores how greenwashing can be addressed through ESG disclosures, regulation, and compliance frameworks using policy or mixed-methods analysis. | Ongoing | [34] | Important for rural development policies to integrate anti-greenwashing measures in subsidy programs, certifications, and local food labelling. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grinberga-Zalite, G.; Furmanova, K.; Zeverte-Rivza, S.; Paula, L.; Kindzule, I. Consumer Perceptions of Greenwashing in Local Agri-Food Systems and Rural Tourism. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15191997

Grinberga-Zalite G, Furmanova K, Zeverte-Rivza S, Paula L, Kindzule I. Consumer Perceptions of Greenwashing in Local Agri-Food Systems and Rural Tourism. Agriculture. 2025; 15(19):1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15191997

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrinberga-Zalite, Gunta, Ksenija Furmanova, Sandija Zeverte-Rivza, Liga Paula, and Inita Kindzule. 2025. "Consumer Perceptions of Greenwashing in Local Agri-Food Systems and Rural Tourism" Agriculture 15, no. 19: 1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15191997

APA StyleGrinberga-Zalite, G., Furmanova, K., Zeverte-Rivza, S., Paula, L., & Kindzule, I. (2025). Consumer Perceptions of Greenwashing in Local Agri-Food Systems and Rural Tourism. Agriculture, 15(19), 1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15191997