Landscape Character Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development in Border Insular Areas: A Case Study of Ano Mirabello, Crete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

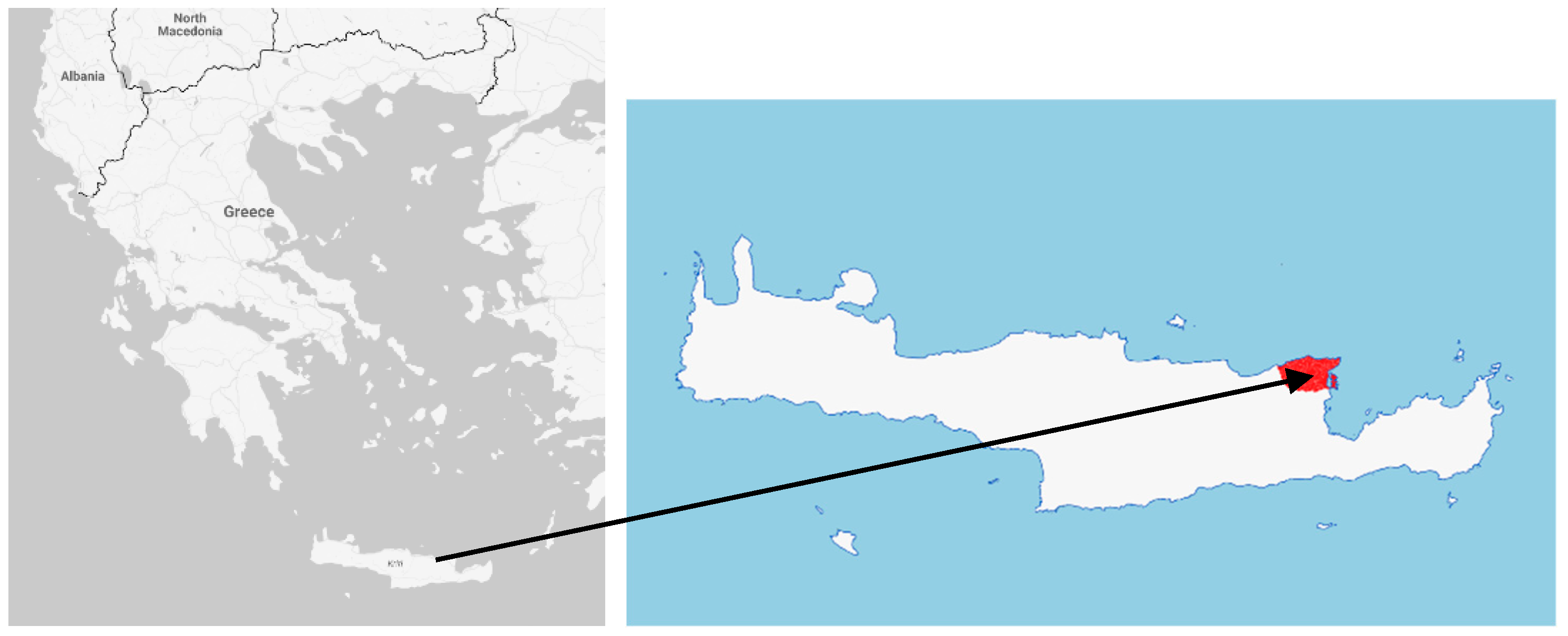

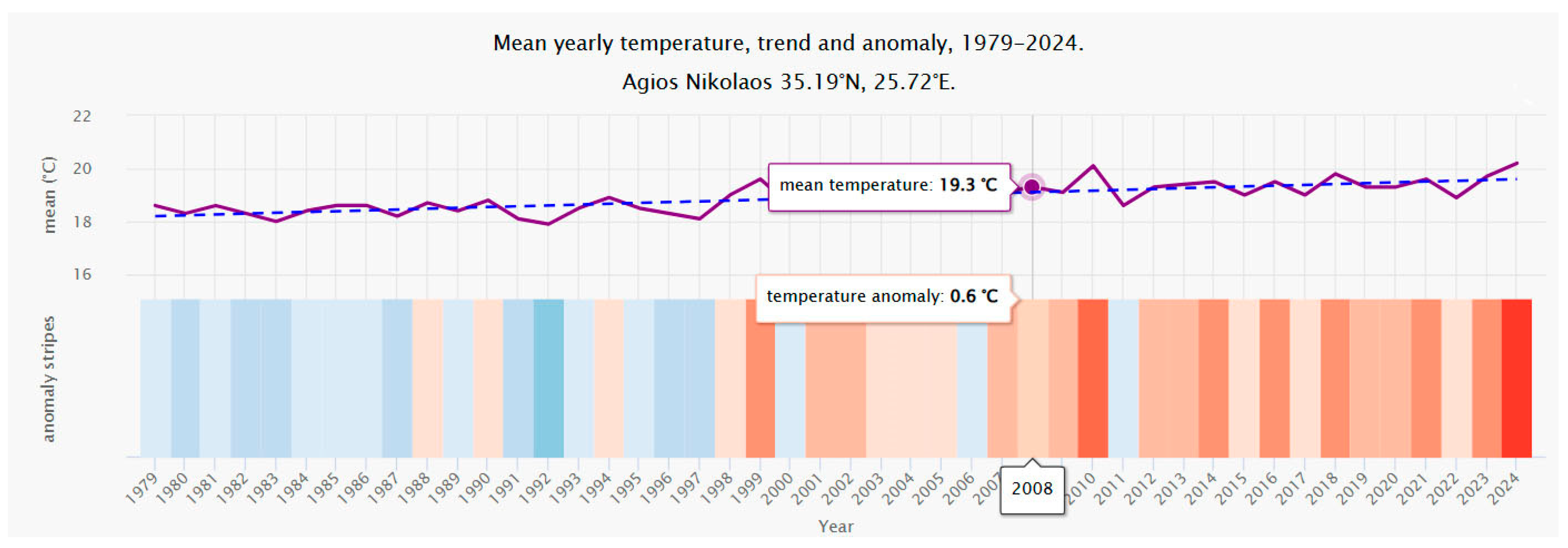

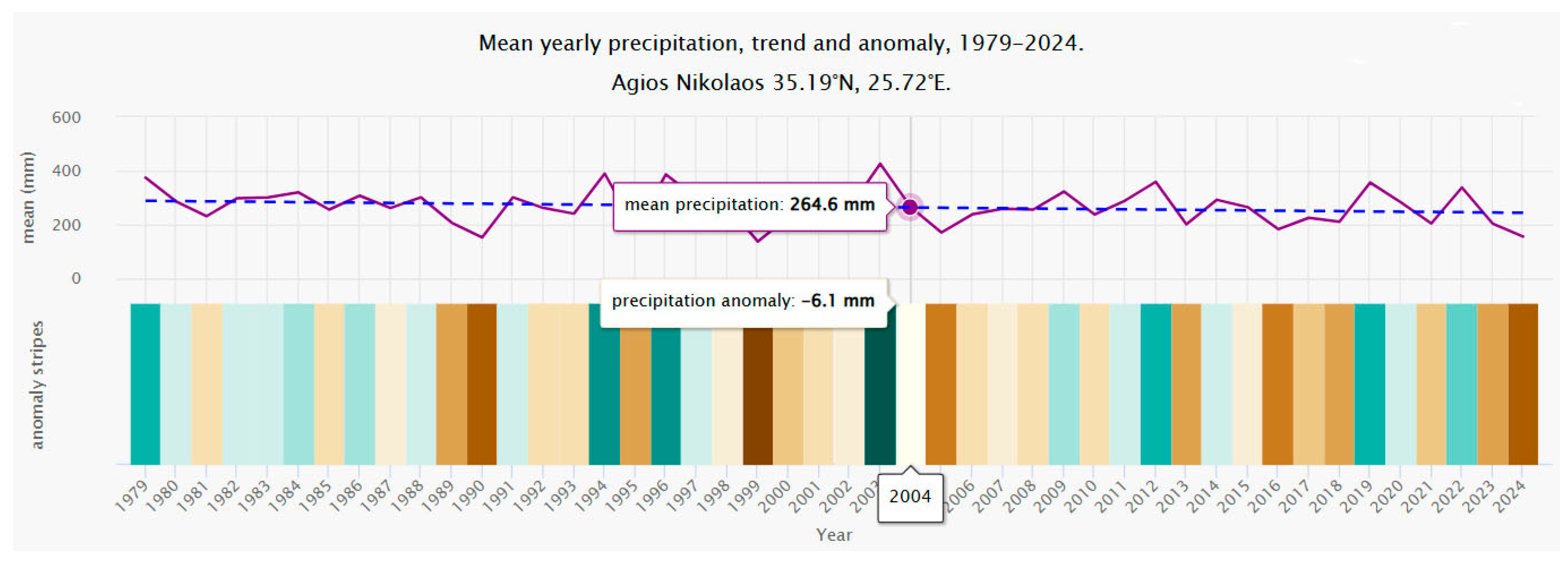

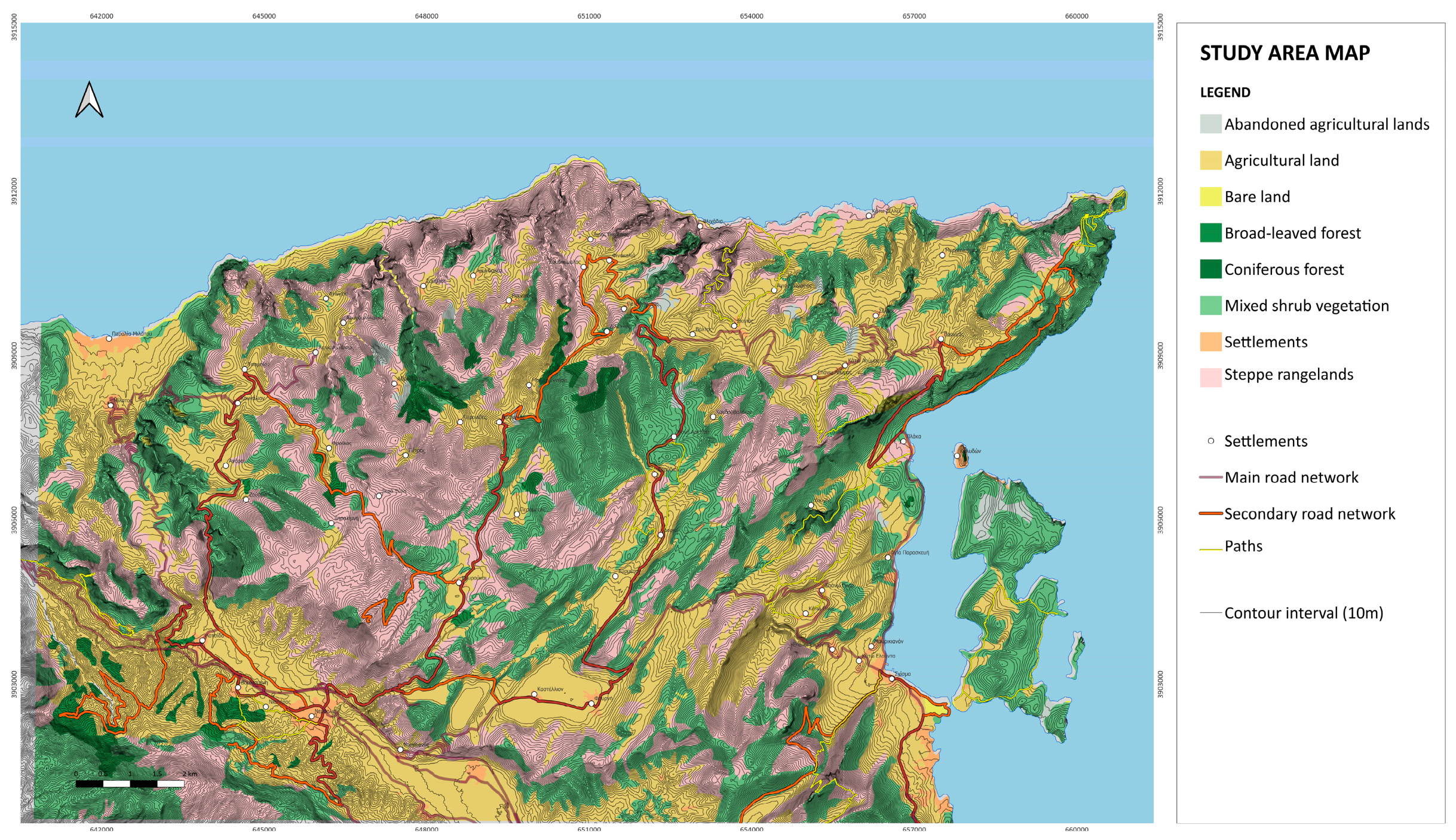

2.1. The Study Area

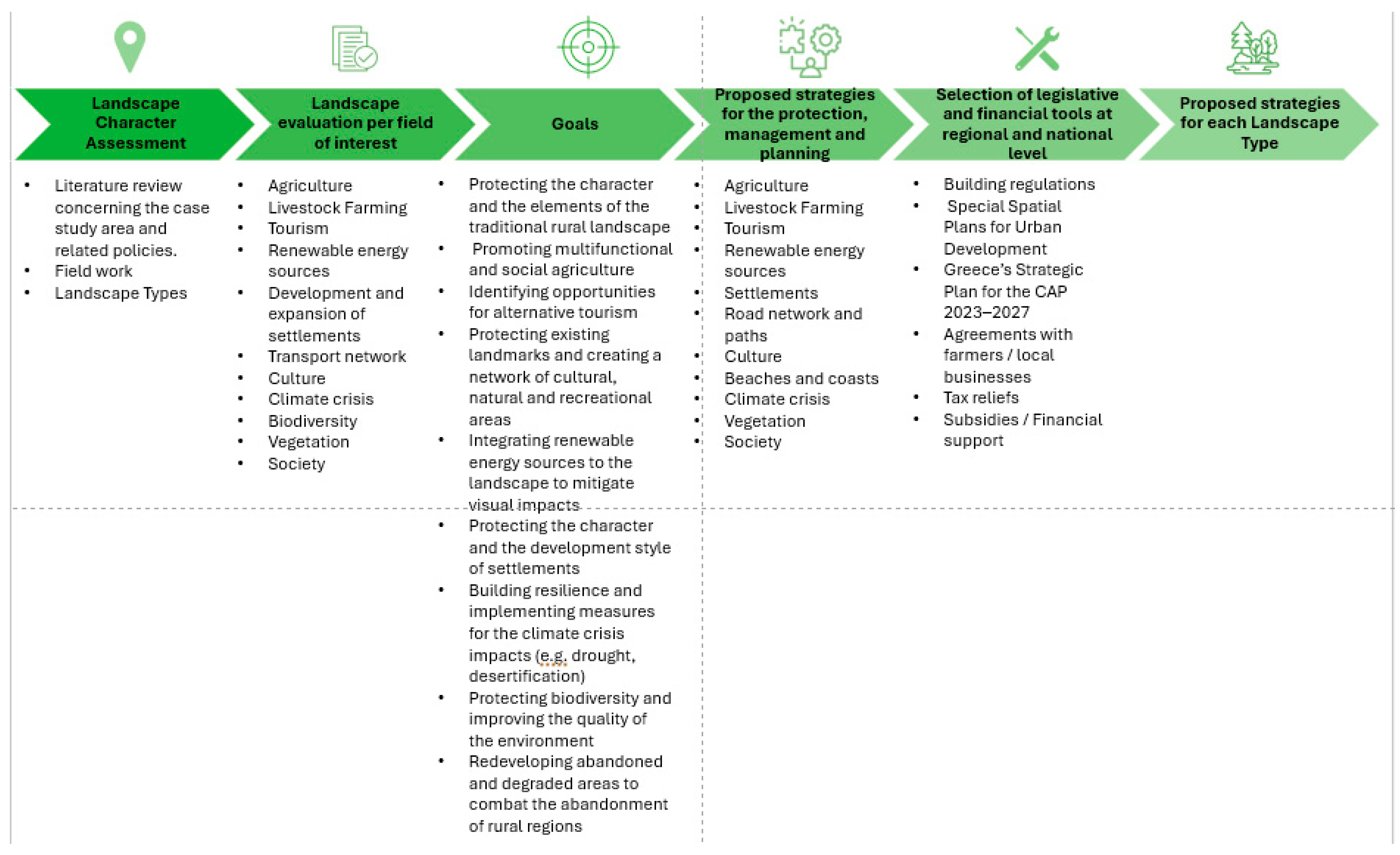

2.2. The Methodological Process

2.2.1. Application of Landscape Character Assessment

- -

- Data pre-processing

- -

- Mapping procedure

- -

- Fieldwork

- -

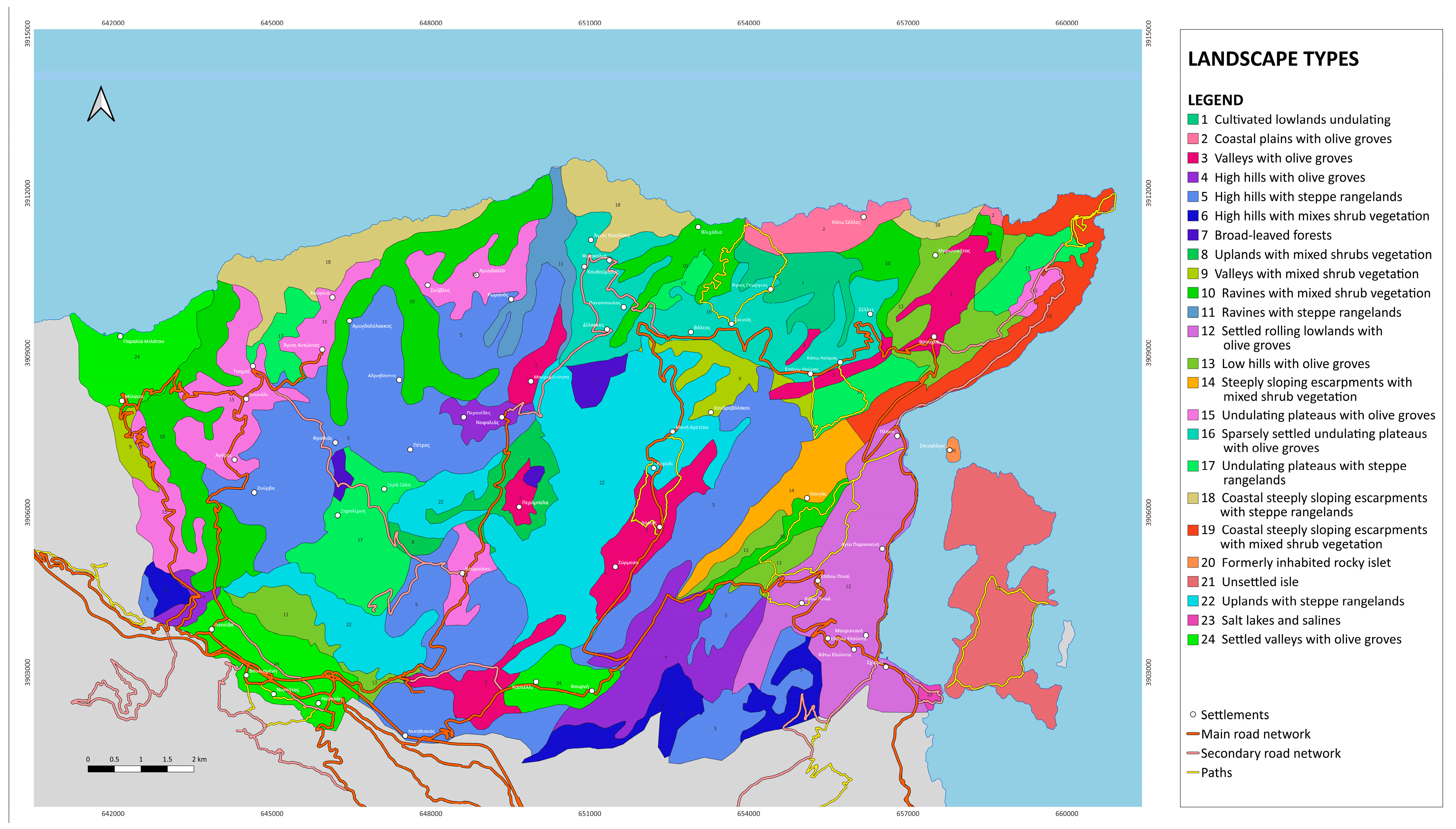

- Landscape types

2.2.2. Landscape Evaluation per Field of Interest

2.2.3. Goals

- ⮚

- Well-preserved and thoughtfully designed landscapes, regardless of type (urban, agricultural, or natural) or character, which are developed through a place-based management model.

- ⮚

- Vibrant and dynamic landscapes capable of accommodating inevitable future spatial transformations without losing their identity and their calm, remote character.

- ⮚

- Heterogeneous landscapes that reflect the rich diversity of the Cretan landscape, taking into account all aesthetic, perceptual, economic, social, and environmental characteristics of the area, including flora, fauna, geological background, as well as historical and cultural elements of particular value.

- ⮚

- Organized and harmonious landscapes that avoid fragmentation and disruption, highlighting existing elements of particular aesthetic and ecological value.

- ⮚

- Unique landscapes that are far from being commonplace.

- ⮚

- Landscapes that maintain and enhance their references and values, both tangible and intangible (ecological, historical, aesthetic, social usage, productive, symbolic, and identity-related).

- ⮚

- Landscapes that always respect the heritage of the past.

- ⮚

- Landscapes that convey tranquility, free from discord, noise, and pollution from light or odors.

- ⮚

- Landscapes that can be enjoyed without jeopardizing their heritage and uniqueness.

- ⮚

- Landscapes that consider social diversity and contribute to the individual and collective well-being of the population, through a combination of educational and recreational opportunities in habitat protection areas and sites of particular geological significance.

3. Results

3.1. Landscape Types

3.2. Assessment of the Situation in Ano Mirabello

- -

- Agriculture: The area is extensively cultivated with olive groves, providing a homogeneous and characteristic agricultural landscape. Unfortunately, most of the dry-stone terraces, which contributed to the preservation of traditional agricultural practices, landscape maintenance, its historical identity, and the region’s cultural heritage are abandoned. As such, the loss of unique features (hedgerows, dry stone constructions, and traditional field patterns), has led to the gradual disappearance of the character of traditional farmland. The appearance of large-scale intensive agricultural facilities becomes more intensive with visual intrusion to dominant locations [40], whereas many infrastructure elements (e.g., photovoltaic panels) have slowly been introduced without any planning.

- -

- Livestock farming: Overgrazing is notable especially in deserted areas, where the loss of pastures, shrubland and forest areas is evident. The remaining livestock structures do not harmonize with the landscape (e.g., animal shelters) and require careful landscape design guidelines.

- -

- Tourism: The area of Ano Mirabello is characterized by unbalanced tourism development. Massive tourism development is dominant along the east coastal areas in Elounda bay, attracting most international and national tourists, whereas the mainland and north coastal part remain undeveloped, limiting visitors’ opportunities to explore the region, its traditions, history, and environment. Therefore, the area faces a diversified tourism development, with a landscape decline and environmental degradation due to increased waste, traffic, and vehicle parking along Elounda bay and abandonment of its natural and cultural environment in the mainland.

- -

- Renewable energy sources: Photovoltaic panels are quite visually intrusive, without proper planning and innappropriate selection of their size [41]. It shows that they are not in harmony with the landscape’s scale, leading to a loss of character. Similarly, the existing wind turbines are visually disruptive into the agricultural landscape, leading to the degradation of the landscape and ridge lines. However, their land cover is still limited and there is space for the appropriate development under specific guidelines.

- -

- Settlement: The area is characterized by the abandonment of traditional villages, despite some scarce efforts for building restoration based on local architecture. On the other hand, the increase in settlement’s expansion along the east coastline is dominant, with diverse construction styles, housing layouts, non-local materials, and ornamental plants, leading to the loss of their unique character and relationship with the existing natural and historic landscape.

- -

- Cultural elements: Most of the archaeological sites including metohia (traditional farm complexes) are neglected. Additionally, important cultural landscape elements such as the windmills, cisterns, and dry stone walls are abandoned and dysfunctional, requiring immediate restoration. There are also historical paths, which although currently lost, offer opportunities for revival and utilization as part of a hiking network, linking cultural and natural points of interest.

- -

- Natural elements: The area hosts a variety of aromatic plants and endemic species, contributing to the uniqueness and ecological value of the landscape; however, the intensive development and subdevelopment of the area creates a risk of biodiversity loss and reduced income from products such as honey and medicinal and aromatic plants. In addition, rapid and drastic changes in land use and vegetation cover may distort the readability and character of the landscape. Additionally, the increase in development along the coastline will cause a decline of coastal ecosystems.

3.3. Proposed Strategies for Protection, Management and Planning

- ⮚

- Strategies aimed at protection: these include proposals for the preservation and maintenance of the features that differentiate the landscape of Ano Mirabello, justified by their cultural, environmental, and economic value, whether intrinsic or resulting from human intervention.

- ⮚

- Strategies aimed at management: these encompass proposals for guiding and harmonizing transformations driven by social, economic, and environmental activities.

- ⮚

- Strategies aimed at planning: these involve proposals related to the evaluation, restoration, and creation of landscapes.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jankilevich, C. Food Security, Agriculture and Landscape. In Future of Landscape Architecture Series: Setting the Foundations for Resilient Landscapes and Communities; Marques, B., Ed.; International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) & The Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington: Wellington, New Zealand, 2023; pp. 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Landscape Convention, Lausanne Declaration on “Landscape Integration in Sectoral Policies”. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/23rd (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Athanasiadou, E.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Agricultural Heritage Landscapes of Greece: Three case studies and strategic steps towards their acknowledgement, conservation and management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPRE. LANDLINES: Why We Need a Strategic Approach to Land. 2017. Available online: https://www.cpre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CPREZLandlinesZ-ZwhyZweZneedZaZstrategicZapproachZtoZland.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the GA on 25 September 2015. 70/1 Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- EC. The Common Agricultural Policy at a Glance. European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/cap-glance_en (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Siakavara, A. Seascape character assessment in Greece. The case of small islands-Gadvos. In The Routledge Handbook of Seascapes, 1st ed.; Pungetti, G., Ed.; The Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, C. Landscape Character Assessment. Guidance for England and Scotland; The Countryside Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage: Sheffield, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Donegal County Council. Draft Seascape Character Assessment of County Donegal; Donegal County Council: Lifford, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LDA Design Consulting LLP. Dorset Coast. Landscape & Seascape Character Assessment; LDA Design Consulting LLP: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Groom, G.; Wascher, D.; Potschin, M.; Haines-Young, R. Landscape character assessments and fellow travelers across Europe: A review. In Landscape Ecology in the Mediterranean: Inside and Outside Approaches, Proceedings of the European IALE Conference, Faro, Portugal, 29 March–2 April 2005; Bunce, R.G.H., Jongman, R.H.G., Eds.; IALE Publication Series 3; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; pp. 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Erikstad, L. Methods for landscape characterization and mapping: A systematic review. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural England. An Approach to Seascape Character Assessment; Natural England Commissioned Report; Natural England: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nogué, J.; Sala, P. Prototype Landscape Catalogue Conceptual, Methodological and Procedural Bases for the Preparation of the Catalan Landscape Catalogues; Observatory de Paisage: Olot/Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzakis, I.; Zomeni, M.; Mannion, A.M. Characterizing Islandscapes: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges Exemplified in the Mediterranean. Land 2017, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Gazette A/30/25 February 2010. Official Gazette L3827/2010. Available online: https://www.kodiko.gr/nomothesia/document/135276/nomos-3827-2010 (accessed on 25 April 2021). (Ιn Greek).

- Aldred, O.; Fairclough, G. Historic Landscape Characterization—Taking Stock of the Method; English Heritage: London, UK, 2003; Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/hlc-taking-stock-of-the-method/ (accessed on 5 June 2003).

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Mougiakou, E. The use of Islandscape character assessment and participatory spatial SWOT analysis to the strategic planning and sustainable development of small islands. The case of Gavdos. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Jaber, N.; Abunnasr, Y.; Abu Yahya, A.; Boulad, N.; Christou, O.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Dimopoulos, T.; Gkoltsiou, K.; Khreis, N.; Manolaki, P.; et al. Travelling in the eastern Mediterranean with landscape character assessment. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment, Paphos, Cyprus, 16–19 March 2015; Hadjimitsis, D.G., Themistocleous, K., Michaelides, S., Papadavid, G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makzoumi, J.; Pungetti, G. Landscape Strategies. In Mediterranean Island Landscapes. Natural and Cultural Approaches, 1st ed.; Vogiatzakis, I.N., Pungetti, G., Mannion, A.M., Eds.; Landscape Series; Springer: Aberdeen, UK, 2008; Volume 9, ISBN 978-1-4020-5063-3. [Google Scholar]

- Makzoumi, J. Olive multifuntional landscapes in Cyprus: Sustainable planning of Mediterranean rural heritage. In Landscape Approaches for Ecosystem Management in Mediterranean Islands, 1st ed.; Conrad, E., Cassar, F.L., Eds.; Institute of Earth Systems, University of Malta: Msida, Malta, 2012; Volume 9, ISBN 978-1-99957-812-1-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Forczek-Brataniec, U. The Role of Landscape Architecture Profession Recognition in the Context of Facing Contemporary Challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullotta, S.; Barbera, G. Mapping traditional cultural landscapes in the Mediterranean area using a combined multidisciplinary approach: Method and application to Mount Etna (Sicily; Italy). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center of Environmental Education Neapolis, Crete. Nofalias: Travel to Nature and Tradition; Center of Environmental Education: Neapolis, Crete, Greece, 2007. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Apostolakou, V.; Sorou, M. Mirabello: The Place and History (Vol. A&B); Municipality of St Nikolaos, Archaeological Department: Lasithi, Greece, 2023. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- ΕΜΥ. National Meteorological Service. Available online: https://www.emy.gr (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Kipriotakis, Z. Contribution to the Study of the Chasophytic Flora of Crete and to Its Managment, as a Natural Resource, to the Direction of Ecotourism, Flori-Culture, Ethnobotary and the Protection of the Threatened Plant Species and Their Biotopes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Patras, Patras, Greece, 1998. (In Greek) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelopoulou, M.; Christidis, C.; Metohi, V. Ano Mirabello: A Landscape Restoration Proposal and Development of Mild Forms of Livestock Farming. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Crete, Chania, Greece, 2021. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Arakadaki, M. Nofalias Mirabello: The Contribution to Architecture of Mountainous Settlements of Crete; Center of Environmental Education Neapolis, Crete: Neapolis, Greece, 2006. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Papanastasis, V.P.; Kazaklis, A. Land use changes and conflicts in the Mediterranean-Type ecosystems of Western Crete. In Ecological Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greek Democracy, Region of Crete. Available online: https://2021-2027.pepkritis.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/SEA_CRETE-2021-2027_Final_V02_R01_28102021.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2023). (Ιn Greek).

- Goulidaki, M. A Design Proposal of the Municipal Garden of Lasithi, Crete. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Crete, Chania, Greece, 2011. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Skoutelis, N.; Stavroulaki, M.; Maravelaki, P. Cultural routes and rehabilitation of the drystone rainwater cisterns of Epano Mirabello region, Crete. In The Safeguard of Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean Basin, Proceedings of the 5th International Congress Science and Technology, Istanbul, Turkey, 22–25 November 2011; Crete Technical University Institutional Knowledge Base: Crete, Greece, 2011; Available online: http://purl.tuc.gr/dl/dias/E919CDEF-0B72-4A90-B1F2-DCFDCBCFF524 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Warknock, S. The Living Landscape Project: Landscape Characterization, Handbook: Level 2. Version 4.1; Department of Geography, The University of Reading: Reading, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick, C.; Cole, L.; Diacono, M. Interim Landscape Character Assessment Guidance; The Countryside Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage: Scotland, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzakis, I. Mediterranean Experience and Practice In Landscape Character Assessment. Ecol. Mediterr. 2011, 37, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiatzakis, I.N.; Griffiths, G.H.; Cassar, L.F.; Morse, S. Mediterranean Coastal Landscapes. Management Practices, Typology and Sustainability, Final Report; The University of Reading: Reading, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevopoulos, G. A Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment Study for the Project: Regional Operational Program, 2021–2027; Report; Region of Central Greece: Crete, Greece, 2022. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kloutsinioti, O.; Katselis, I. Omikron Ltd. Evaluation of the Implementation of Spatial Territorial Plans of Crete; Ministry of Environment & Energy: Crete, Greece, 2011. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Siriphanich, S.; Angsuratana, A.; Kalpax, T.; Tepwongsirirat, P. Landscape design guidelines for agro-tourism locations: A case study of Subsanoon visitor center, Saraburi, Thailand. Acta Hortic. 2013, 999, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremke, S.; Oudes, H.H.; Picchi, P. (Eds.) Power of Landscape: Novel Narratives to Engage with the Energy Transition; NAi010: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzakis, I.N.; Mannion, A.M.; Pungetti, G. (Eds.) Introduction to the Mediterranean Island Landscapes. In Mediterranean Island Landscapes. Natural and Cultural Approaches, 1st ed.; Landscape Series; Springer: Aberdeen, UK, 2008; Volume 9, ISBN 978-1-4020-5063-3. [Google Scholar]

- Oliviera, R.; Guiomar, N. Landscape character assessment and regional landscape strategy in the Azores, Portugal. In Island Landscapes. An Expression of European Culture; Routledge, Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pungeti, G. Island Landscapes. An Expression of European Culture; Routledge, Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rackham, O.; Moody, J. The Making of the Cretan Landscape; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996; Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA29702273 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Benedeto, G.; Giordano, A. Mediterranean Island Landscapes. Natural and Cultural Approaches; Vogiatzakis, I.N., Pungetti, G., Mannion, A.M., Eds.; Landscape Series; Springer: Sicily, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alipour, M.; Jafari, H.; Alizadeh, K. The effect of cultivation of medicinal plants on the economic development of rural settlements Case study: Villages of Kalat city. Propósitos Represent. 2021, 9, e957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capucho, J.; Paço, A.D.; Gaspar, P.D. Tourism Related to Aromatic and Medicinal Plants: Some Practical Evidence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Ahern, J. Adaptive planting design and management framework for urban climate change adaptation and mitigation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M.; Stroma, C.; Reeves, K.J.; Kato, K. Tourism and islandscapes: Cultural realignment, social-ecological resilience and change. Shima 2017, 11, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, P.; Puigbert, L.; Bretcha, G. Landscape Planning at Local Level in Europe; Landscape Observatory of Catalonia, Government of Andorra: Andorra la Vella, Andorra, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Landscape Convention; ETS No 176; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- IFLA. A Landscape Architectural Guide to the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals; IFLA, Universita Polytechnica de Catalunyna: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Landscape Institute. Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment; Spon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Symons, N.P.; Vogiatzakis, I.N.; Griffiths, G.H.; Warnock, S.; Vassou, V.; Zomeni, M.; Trigkas, V. Geospatial Tools for Landscape Character Assessment in Cyprus. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2013), Paphos, Cyprus, 8–10 April 2013; Hadjimitsis, D.G., Themistokleous, K., Michaelides, S., Papadavid, G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 87951B. [Google Scholar]

- Terkenli, T.; Gkoltsiou, A. Landscape Character Assessment (LCA). Reports of Level 1 & Level 2 for Lesvos, Greece; ΜΕDSCAPES. (ENPI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin-2007–2013); Department of Geography, University of the Aegean: Lesvos, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gourgiotis, A.; Tsilimigkas, G. Landscape Management in Spatial Planning. In Aeixoros. Essays on Spatial Planning and Development; Department of Planning and Regional Development, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly: Volos, Greece, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- David Tyldesley and Associates. Fife Landscape Character Assessment; Scottish Natural Heritage: Edinburgh, Scotland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Protection | Management | Planning/Design | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Preservation of small-scale farms. | Providing financial incentives to engage young people in the primary sector. | Integration of agricultural facilities (such as warehouses, machinery, etc.) into the landscape. |

| Cultivation of resilient crop varieties. | Seeking solutions through agritourism (e.g., programs for learning and applying traditional agricultural practices). | Preservation of traditional dry-stone constructions and planting small trees and shrubs at field boundaries to ensure habitat continuity. | |

| Preservation of traditional agricultural practices. | Crop rotation to maintain soil fertility. | ||

| Livestock farming | Implementation of rotational grazing systems in zones to address overgrazing. | Integration of livestock facilities into the landscape using vegetation and dry-stone constructions. | |

| Tourism | Promotion of historical monuments. | Enhancing tourism in a manner consistent with the area’s character. | Providing guidelines for the design of infrastructure and activities related to tourism. |

| Promotion of harvest events. | Developing agritourism as a tool for managing local agricultural elements. | Utilization of aromatic plants that grow in the area, offering many opportunities for the tourism sector. | |

| Developing gastronomic tourism. | Designing cultural routes that connect the area’s history and tradition. | ||

| Renweable energy sources | Conducting Environmental Impact Assessments before installing renewable energy systems. | Financial and technical support for the development of renewable energy sources. | Creation of multifunctional landscapes where renewable energy sources are integrated into other productive sectors |

| Creating energy communities. | Proper spatial planning and sizing of photovoltaic installations. | ||

| Preservation of the open, natural, and rural landscape character by limiting the development of wind turbines, especially on ridge lines. | |||

| Settlements | Guidelines regarding the architecture of new buildings and infrastructure. | ||

| Adoption of policies guiding the proper restoration of existing traditional buildings. | |||

| Recognition and promotion of exemplary cases of new building construction. | |||

| Road network and paths | Restriction of vehicles in ecologically sensitive areas. | Creating a trail network connecting the area’s landmarks. | Concealing unsightly land uses visible from the main road network. |

| Culture | Protection of archaeological sites, monasteries, horseshoe-shaped windmills, rainwater tanks, and dry-stone constructions. | Awareness programs on the architectural heritage of the region. | Appropriate landscape design of archaeological sites to improve accessibility, and harmonization with the landscape. |

| Financial incentives for the restoration of cultural elements of the rural landscape. | Developing a management plan for the archaeological sites in the area. | ||

| Beaches and coasts | Enhancement of vegetation along water corridors and coasts. | Improving the management of waste, sewage, and debris on the coasts. | Design and management of coastal access and parking areas. |

| Climate crises | Collaborations with universities to apply innovative solutions for protection. | Utilizing traditional water management practices (rainwater tanks, terraces). | |

| Restoration of rainwater tanks for water storage. | Tree-planting programs to combat soil erosion. | ||

| Identification of vulnerable areas. | |||

| Public awareness campaigns. | |||

| Vegetation | Monitoring and reducing the spread of invasive species such as Sarcopoterium spinosum | Emphasizing the pronounced seasonal changes in vegetation through planning | |

| Preserving native vegetation in olive tree cultivations. | The proposed palette of plant species should include endemic species. | ||

| Society | Development of a culture among residents regarding land conservation and rural landscape preservation | Better management and utilization of the area’s aromatic plants | |

| Creation of cooperatives for economic development through local traditions and knowledge | Providing infrastructure to attract digital nomads |

| Fields of Interest | Strategies for Planning | Landscape Types | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | ||

| Agriculture/Livestock farming | Integrating photovoltaic panels into existing crops, creating multifunctional landscapes. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Integration of agricultural infrastructures into the region’s landscape through the use of plant material, dry-stone constructions, and appropriate siting. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Integration of new crops, taking into account the existing field patterns and terrain of the area. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exploration of possibilities for planting small trees and shrubs at the edges and corners of fields to ensure continuity of natural habitats. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tourism | Promotion of significant archaeological sites (sunken city of Olous, Mosaic of the Early Christian Basilica of Poros Elounda) and landmarks (Windmills of Poros Elounda, Chapel of Saint Luke) through appropriate development of the surrounding area and visitor information. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restoration of the Elounda estate complex to an information center for the region and coordinating actions for the development and promotion of the area. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For better integration of tourist facilities into the landscape, it is proposed that planting designs do not follow strict linearity but rather more natural developments, contributing to the unification of different areas. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renewable energy sources | Careful planning and selection of the size of the proposed photovoltaic panels, and concealing existing ones with appropriate planting. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conducting landscape studies for the proper placement of wind turbines, limiting their development to the ridgelines, and choosing locations where the visual impacts on significant views and the local residents will be minimal. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Settlements | The expansion and organization of settlements should follow the urban planning regulations and provisions of the area, without negatively intruding into the landscape. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Every form of development should be designed and sited so that it integrates into the landscape, considering the views, relief, and natural character of the area, so as not to cause visual disturbance to the landscape and its distinctive features. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Development of traditional settlements such as Finokalia, as an educational and research center for the region, based on the Finokalia Environmental Observatory. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Road network and paths | Creation and enhancement of pathways. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Culture | Connecting the significant elements of the area to the broader network of cultural routes that will highlight the history and traditions of the region | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creation of a network of walking routes and connection with the traces of trails dating back to the Venetian period. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creation of walking routes that will connect the natural, religious, cultural, and historical landmarks of the area. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connecting the area with the archaeological sites and landmarks located in Kolokytha through the existing walking routes, with appropriate signage. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beaches and coasts | The coasts should have access, where feasible, through an organized and safe trail network that will create interesting hiking routes. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural Environment | Enhancement and completion of tree-lined avenues as landscape unification elements (eucalyptus trees between the settlements of Kastelli and Fournis, cypress trees at Monastery of Xera Xyla). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Showcasing the natural wealth of the area through the creation of an organized and safe trail network. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fields of Interst | Strategies for Management | Landscape Types | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | ||

| Agriculture | Maintenance of indigenous vegetation in olive tree plantations for better integration into the landscape. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Promotion of the cultivation of aromatic plants and strengthening of this sector to enhance the local economy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Provision of financial incentives to allow young farmers to engage in new crops, beyond olive cultivation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tourism | Development of gastronomic tourism combining wine tasting, cooking lessons, and visits to local farms. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Development of a management plan for the archaeological sites located in the area, aiming to make some of them accessible to the public (archaeological site of Driro, Pinos tower, ancient Olous). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Management of visitor access to the island Kolokitha and parking areas, aiming to control disturbance levels, especially during the summer months. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renweable energy sources | Utilization of the rooftops of hotels for the installation of photovoltaic panels to avoid increasing the energy burden on the wider area. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Settlements | Compose a maintenance plan for derelict traditional settlements | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Road network and paths | Highlighting the existing trails and viewpoints along the route. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enhancement and improvement of existing walking routes to enable visitors to enjoy the religious and historical monuments. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Culture | Highlighting the landscape of the salt lakes and integrating them into a wider network of salt pans in the Mediterranean and Europe, with the ultimate goal of protecting and preserving their historical memory. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beaches and coasts | The installation of illegal constructions, which dominate the landscape and distort its coastal character, should be avoided. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Waste and wastewater management in the area should be carried out through an organized plan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural Environment | Maintenance of dry-stone structures to prevent soil erosion and enhance biodiversity. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Promotion of research programs for the cultivation of experimental fields aimed at enhancing local meadows to limit the spread of Sarcopoterium spinosum. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maintenance of indigenous vegetation in olive tree plantations for enhancement of biodiversity and landscape connectivity. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Controlled rotational grazing for the restoration of vegetation and eroded soil. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Due to the sensitivity of this specific landscape type, it is important to implement a gradation in access and uses, with the aim of protecting its ecologically sensitive features and mitigating the adverse effects caused by human activities on the landscape. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic monitoring of soil and vegetation conditions to assess the impacts and take corrective measures. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fields of Interst | Strategies for Protection | Landscape Types | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | # | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | ||

| Agriculture | Restoration of dry-stone structures to preserve traditional agricultural practices. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protection of the boundaries of cultivated land bordering the settlement of Elounda and establishment of measures for the preservation of fields, which provide a historical continuity to the landscape and enhance local biodiversity. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Avoidance of intensive olive cultivation to preserve the traditional field patterns and terrain of the area, which are adapted to the scale of Upper Mirabello. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Settlements | Preservation of the open, highly visible, and sparsely populated character of this specific Landscape Type. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Any incompatible use (e.g., photovoltaic panels) should be discouraged so that the character of the landscape of this specific type, and more broadly, is maintained, taking into serious consideration the intense alteration the Elounda bay has undergone. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Culture | Restoration of rainwater collection tanks to promote the region’s historical heritage and to strengthen water management. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restoration and highlighting of the horseshoe-shaped windmills of the area. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restoration and utilization of the metochia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preservation of the character of the historical and natural landscape of Spinalonga as well as the surrounding coastlines through adherence to landscape protection provisions and urban planning regulations for the area. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beaches and coasts | Preservation of the natural and wild character of the coastal steep slopes and shores, preventing any form of massive tourism development. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural Environment | Restoration of existing inactive quarries north of the settlement of Latsida. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protection of the wetland of the salt pan area with a specific management plan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protection and management of broadleaf forests due to their uniqueness within the landscape. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkoltsiou, A. Landscape Character Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development in Border Insular Areas: A Case Study of Ano Mirabello, Crete. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15101020

Gkoltsiou A. Landscape Character Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development in Border Insular Areas: A Case Study of Ano Mirabello, Crete. Agriculture. 2025; 15(10):1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15101020

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkoltsiou, Aikaterini. 2025. "Landscape Character Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development in Border Insular Areas: A Case Study of Ano Mirabello, Crete" Agriculture 15, no. 10: 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15101020

APA StyleGkoltsiou, A. (2025). Landscape Character Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development in Border Insular Areas: A Case Study of Ano Mirabello, Crete. Agriculture, 15(10), 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15101020