Agricultural and Industrial Heritage as a Resource in Frontier Territories: The Border Between the Regions of Andalusia–Extremadura (Spain) and Alentejo (Portugal)

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

- To identify and examine legal frameworks and territorial disputes between countries and Spanish Autonomous Communities, in order to assess how these influence the protection and management of heritage assets in border areas.

- To analyze spatial data and territorial boundaries within the study area, with the aim of illustrating the disconnect between administrative borders and the continuity of cultural landscapes.

- To investigate the historical and current role of rural productive systems—particularly agricultural structures—as a basis for understanding their cultural and territorial significance.

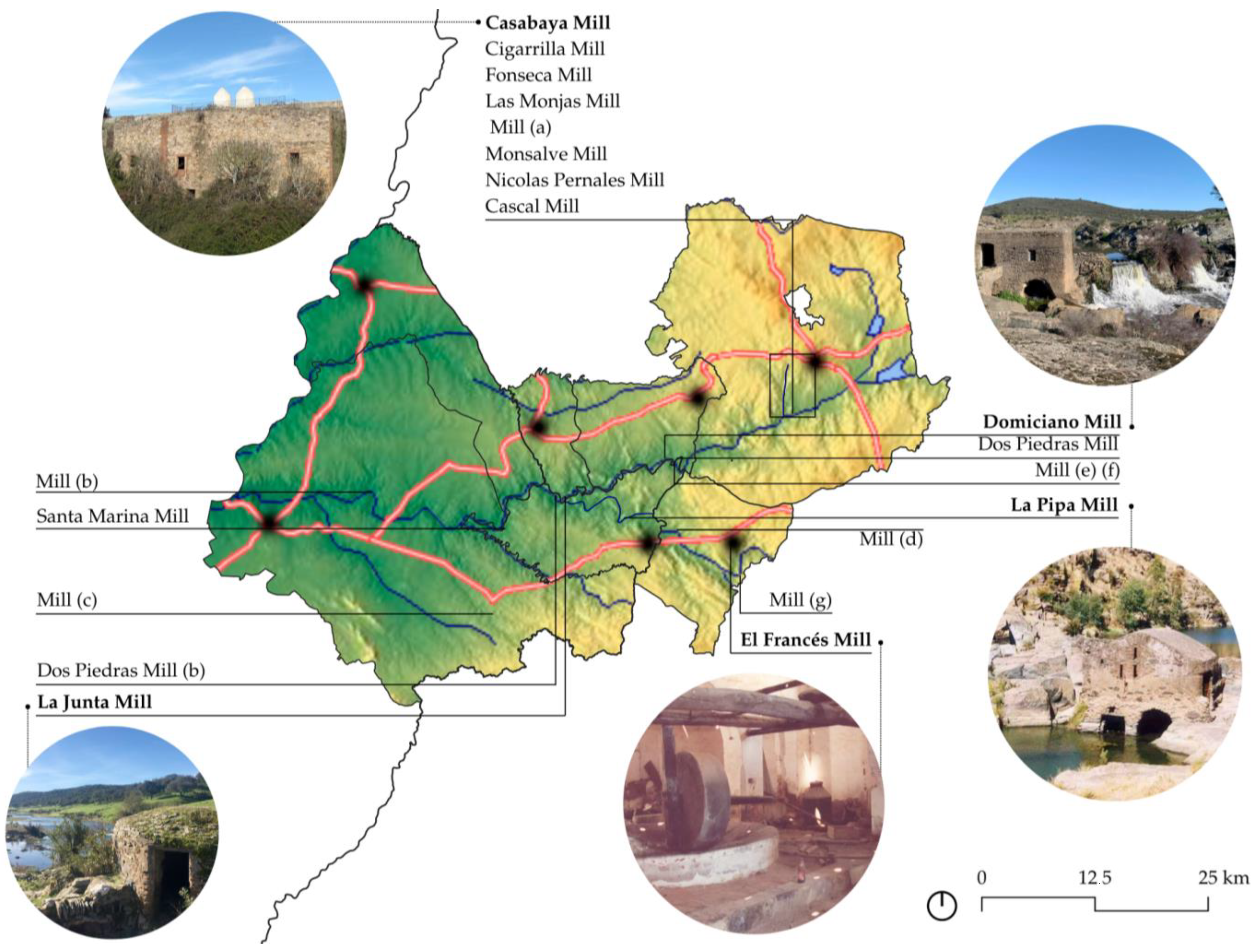

- To compile, geolocate, and classify existing mills within the study area using fieldwork and archival data, in order to evaluate their distribution, typologies, and current condition.

- To develop informed protection strategies for the identified heritage assets, based on their cultural value, spatial patterns, and vulnerability within a cross-border context.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

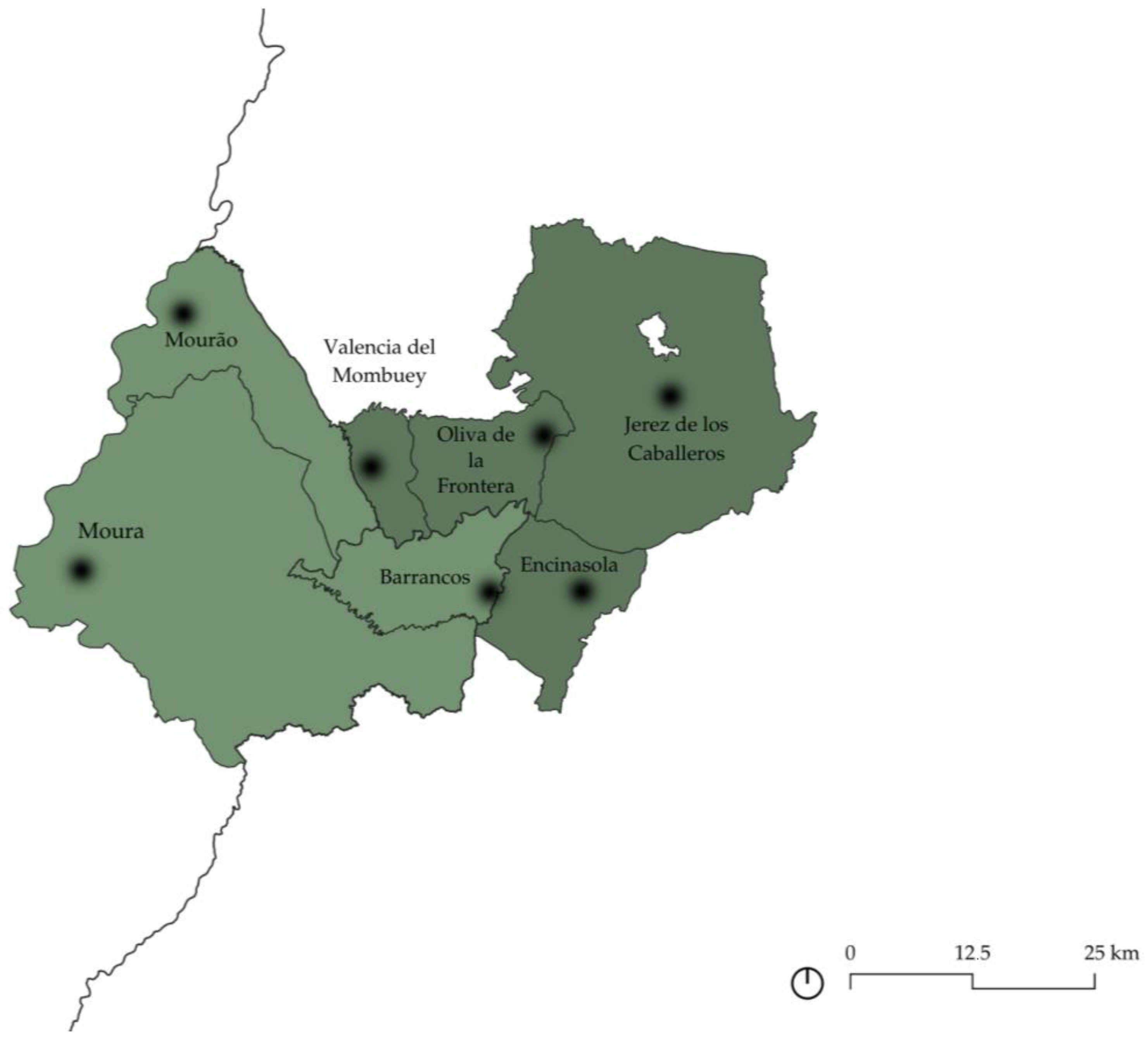

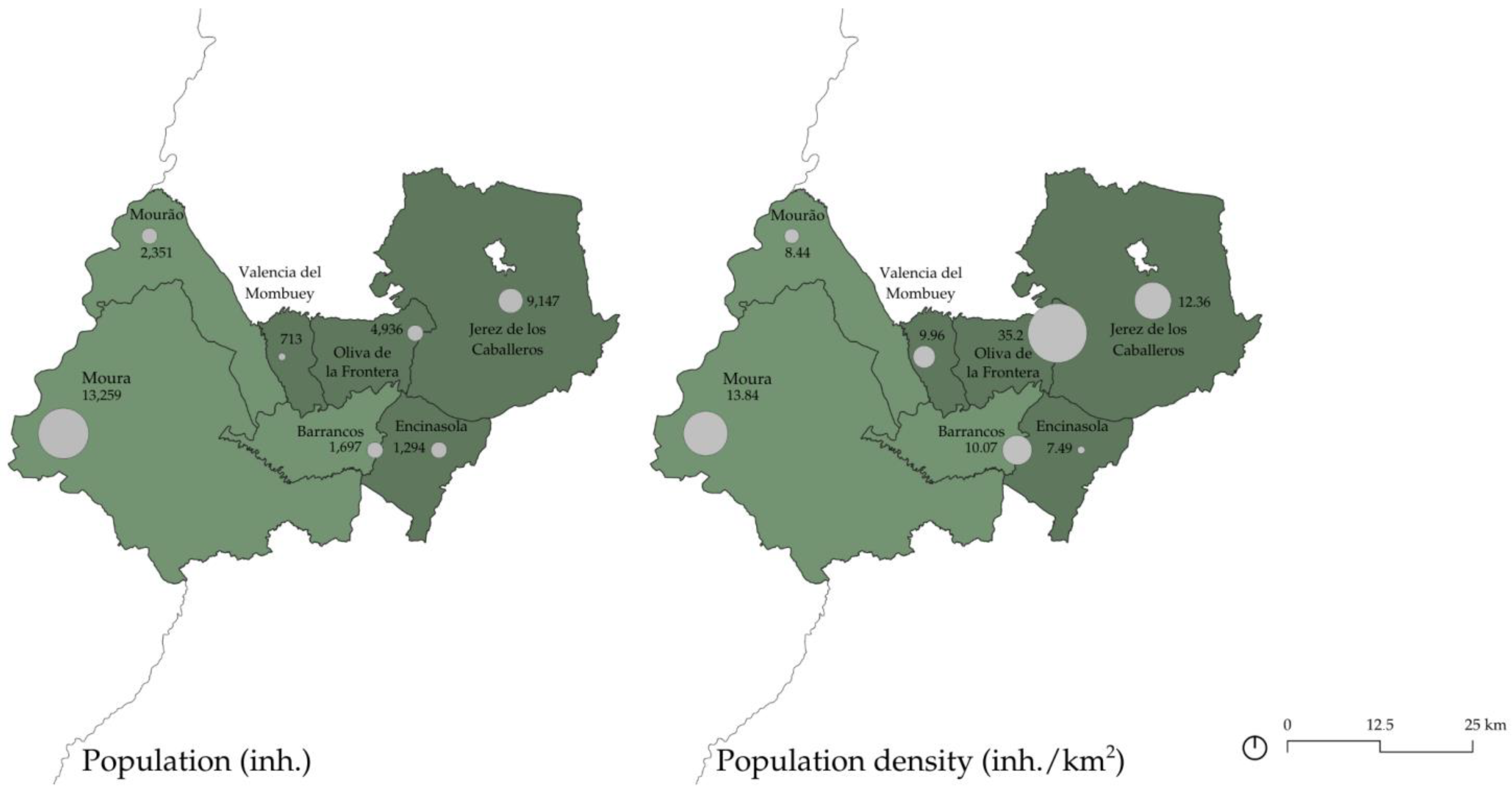

3.1. Settlement Framework

3.2. Legal Framework

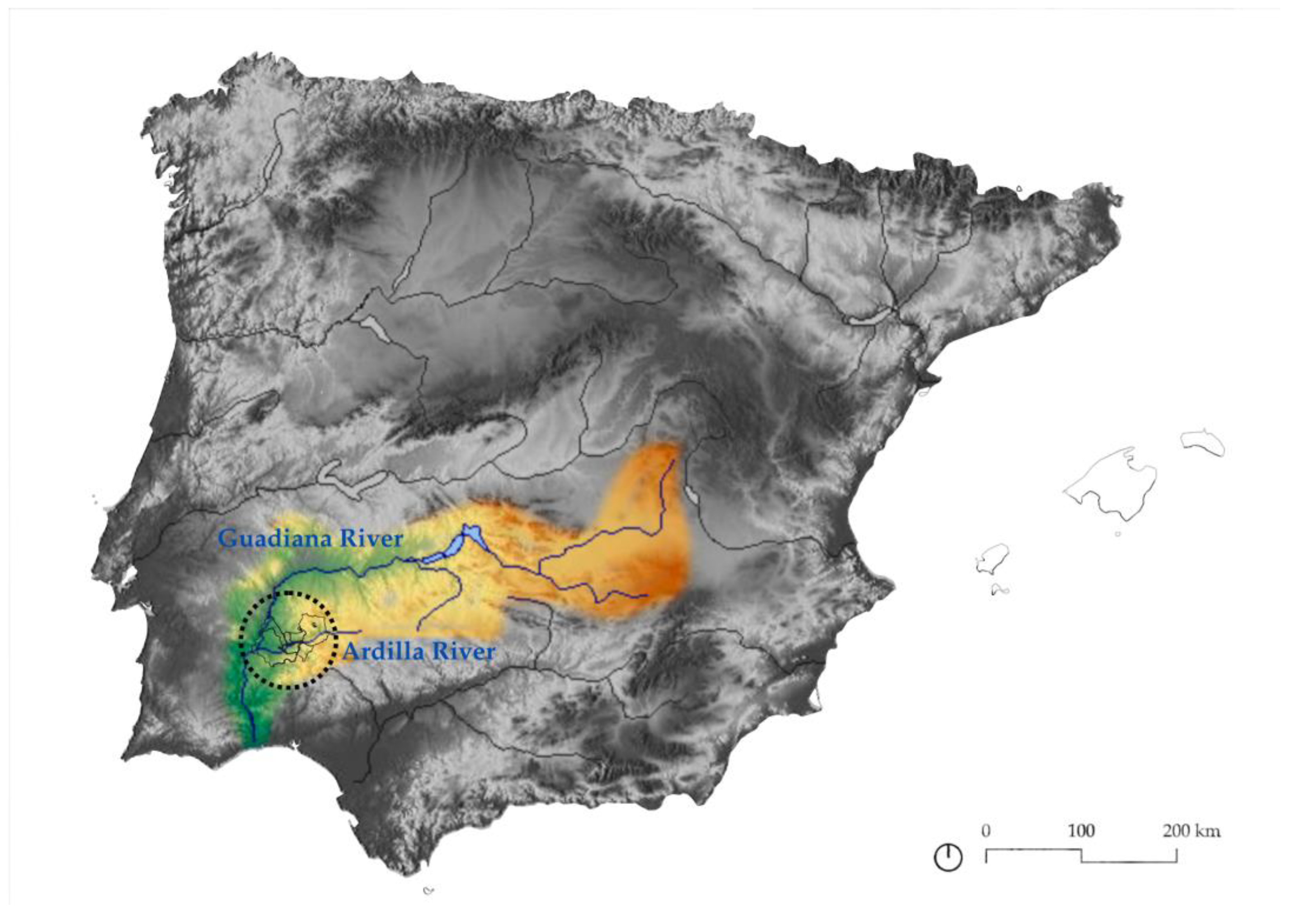

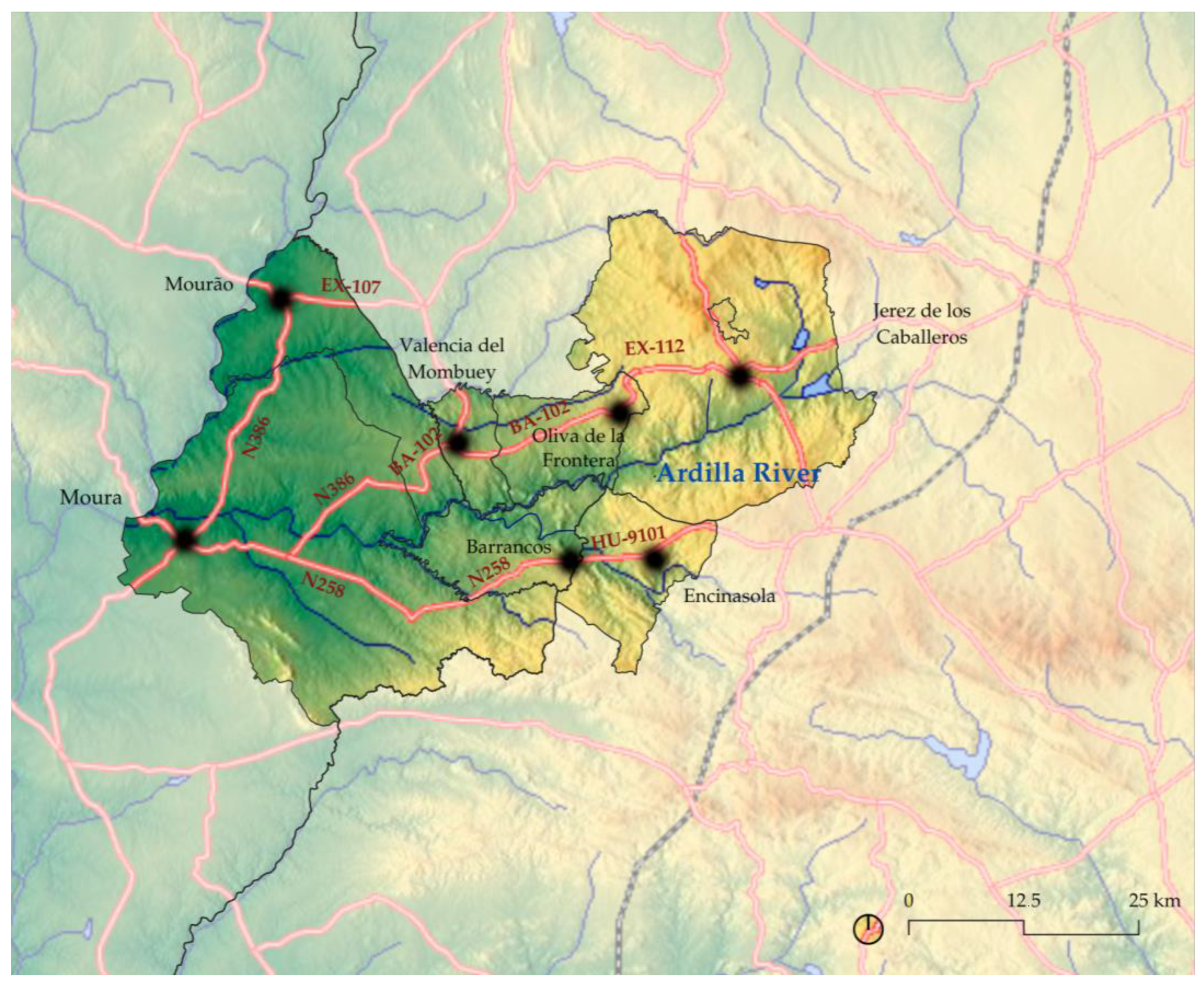

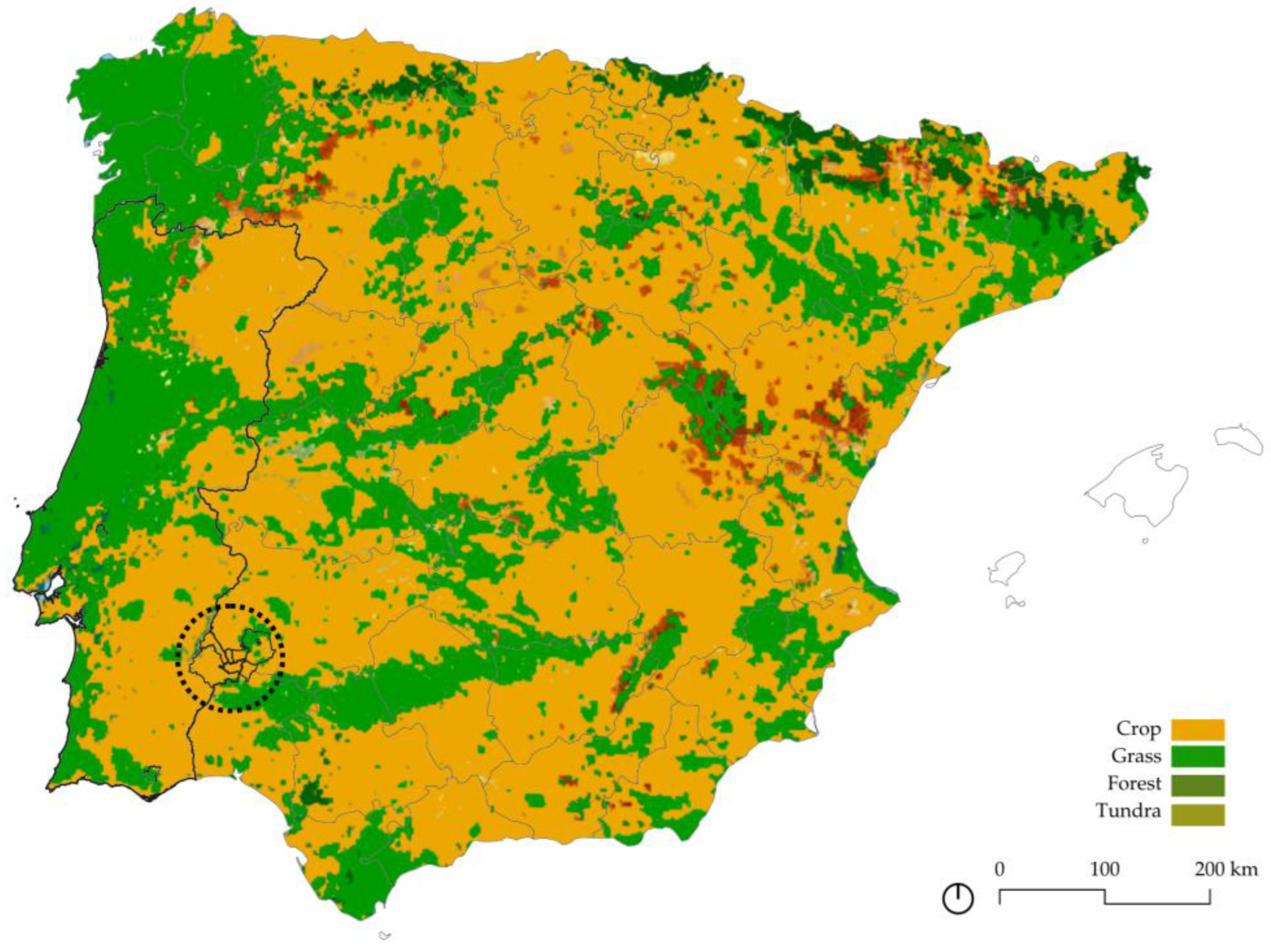

3.3. Physical Framework

3.4. Production Framework

3.5. Agricultural Heritage Framework

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez Cano, M.T.; Maruri Arana, A. Cultural Landscape and Heritage as an Opportunity for Territorial Resilience—The Case of the Border Between Castile and Leon and Cantabria. Land 2024, 13, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Ruiz, J. Carta de Baeza Sobre Patrimonio Agrario; Universidad Internacional de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lavado Contador, J.F. Introducción a la vegetación y la fauna de Extremadura. In Patrimonio Geológico de Extremadura; Muñoz Barco, P., Martínez Flores, E., Eds.; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Mexico, 2010; pp. 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Jiménez, M.I. Patrimonio y paisaje en España y Portugal. Del valor singular a la integración territorial. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2016, 71, 347–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European landscape convention. In Report and Convention; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Melón Jiménez, M.A. Las fronteras de España en el siglo XVIII. Algunas consideraciones. Obradoiro Hist. Moderna 2010, 19, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ICOMOS. Principles on Rural Landscapes as Heritage. In Proceedings of the 19th ICOMOS General Assembly, Delhi, India, 11–15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Salinas, V.; Romero Moragas, C. El Patrimonio Local y el Proceso Globalizador. Amenazas y Oportunidades. Tendencias Futuras en la Gestión Local del Patrimonio; Asociación Para el Desarrollo Rural de Andalucía: Granada, Spain, 2008; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Ruiz, J. El patrimonio cultural podría estar en peligro y los responsables son la memoria, la salvaguardia, la comunidad y el paisaje cultural (además del turismo, claro). Erph Rev. Electrónica Patrimonio Histórico 2021, 28, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2005; Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- ICOMOS–TICCIH. Principles for the Preservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes (The TICCIH Charter). 2003. Available online: https://ticcih.org/about/about-ticcih/dublin-principles/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. 1999. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/publications/burra-charter-practice-notes/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Biel, A.; Bergström, G.; Henriksson, M. Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability; Swedish National Heritage: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strangleman, T. “Smokestack nostalgia”, “ruin porn” or working-class obituary: The role and meaning of deindustrial representation. Int. Labor Work. Cl. Hist. 2013, 84, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPAB (Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings). SPAB Mills Section. Available online: https://www.spab.org.uk/mills (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Rijksdienst Voor Het Cultureel Erfgoed. Monumenten Inventarisatie Project (MIP). Available online: https://cultureelerfgoed.nl/onderwerpen/monumenten-inventarisatie-project-mip (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- del Espino Hidalgo, B.; Rodríguez Díaz, V.; González-Campos-baeza, Y.; Santana Falcón, I. Accessibility Indicators for the Assessment of Cultural Heritage as a Resource for Development in Rural Areas of Huelva. Archit. City Environ. 2022, 50, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.A.C. Notas sobre la ganadería de la Sierra de Huelva en el s. XV. Historia. Instituciones. Doc. 1994, 21, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Valiente, J.M. La frontera interautonómica de Andalucía: Un espacio periférico, deprimido y desarticulado. Rev. Estud. Andal. 1990, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Valiente, J.M. El borde septentrional onubense: Un espacio “a caballo” entre Andalucía y Extremadura. Huelva Hist. 1992, 4, 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Madoz, P. Diccionario Geográfico-Estadístico-Histórico de España y sus Posesiones de Ultramar; Establecimiento Tipográfico de P. Madoz y L. Sagasti: Madrid, Spain, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Miñano y Bedoya, B. Diccionario Geográfico-Estadístico de España y Portugal; Imprenta de Pierart-Peralta: Madrid, Spain, 1826–1828. [Google Scholar]

- García, E.C.; Valverde, F.A.N.; Martos, J.C.M. Cohesión territorial y subsidio de desempleo agrario. El caso de Andalucía. In Revalorizando el Espacio Rural: Leer el Pasado Para Ganar el Futuro: XVII Coloquio de Geografía Rural, Colorural 2014, Girona, 3–6 September 2014; Documenta Universitaria: Girona, Spain, 2014; p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Diagnóstico de la Igualdad de Género en el Medio Rural; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EPSON. Cross-Border Cooperation—Cross-Thematic Study of INTERREG and ESPON Activities; EPSON: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, M.G.; Fedeli, V. Exploring European urban policy: Towards an EU-national urban agenda? Gestión Análisis Políticas Públicas 2015, 14, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Treaty of Tordesillas, Signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494. Available online: https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/international-relations/europe-and-legal-regulation-international-relations/treaty-tordesillas-june-7-1494 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Rengifo Gallego, J.I.; Sánchez Martín, J.M. El patrimonio en Extremadura: Un mecanismo para la cooperación transfronteriza = The heritage in Estremadura: A tool for the cross border cooperation. Polígonos. Rev. Geografía 2017, 29, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOE. No. 43, February 18, 2010. Official State Bulletin of Spain.

- DECREE 347/2004; Establishing the Organic Structure of the Ministry of the Presidency. 2004.

- BOE. No. 166, of July 9, 2010. Official State Bulletin of Spain.

- BOE-A-1978-31229; Spanish Constitution. Madrid, Spain. 1978.

- Royal Decree 35/2023; Approving the Revision of the Hydrological Plans of the Western Cantabrian, Guadalquivir, Ceuta, Melilla, Segura and Júcar River Basins, and of the Spanish Part of the Eastern Cantabrian, Miño-Sil, Duero, Tajo, Guadiana and Ebro River Basins. 2023.

- Law 107/2001; On the Bases of the Policy and Rules for the Protection and Valorization of Cultural Heritage. Unesco, 2001.

- Organic Law 1/2011; Reforming the Statute of Autonomy of the Autonomous Community of Extremadura. Official Diary of Extremadura, 2011.

- Law 2/1999; On the Historical and Cultural Heritage of Extremadura. Official Diary of Extremadura, 1999.

- Law 8/1998; On the Conservation of Nature and Natural Spaces of Extremadura. Official Diary of Extremadura, 1998.

- Law 14/2007; Of 26 November, on the Historical Heritage of Andalusia. Official Bulletin of the Andalusian Board, 2007.

- Law 1/1991; On the Historical Heritage of Andalusia. Official Bulletin of the Andalusian Board, 1991.

- Garzón Heydt, G. Geomorfología y paisaje extremeño. In Patrimonio Geológico de Extremadura; Muñoz Barco, P., Martínez Flores, E., Eds.; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Mexico, 2010; pp. 70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Amelia, D. Rasgos geomorfológicos de Extremadura. In Aportaciones a la Geografía Física de Extremadura con Especial Referencia a las Dehesas; Schnabel, S., Lavado Contador, F., Gómez Gutierrez, A., García Marín, R., Eds.; Asociación Profesional para la Ordenación del Territorio, el Ambiente y el Desarrollo Sostenible—Fundicotex: Cáceres, Spain, 2010; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- García Marín, R.; Mateos Rodríguez, A.B. El clima de Extremadura. In Aportaciones a la Geografía Física de Extremadura con Especial Referencia a las Dehesas; Schnabel, S., Lavado Contador, F., Gómez Gutierrez, A., García Marín, R., Eds.; Asociación Profesional para la Ordenación del Territorio, el Ambiente y el Desarrollo Sostenible—Fundicotex: Cáceres, Spain, 2010; pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo Guilcapi, J.D. Puesta en Valor del Patrimonio Edificado, Caso de Estudio los Molinos de Agua en el Cantón Guano. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jariego García, A.; Lavado Contador, J.F. Usos del suelo y ganadería en las dehesas de Extremadura. In Patrimonio Geológico de Extremadura; Muñoz Barco, P., Martínez Flores, E., Eds.; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Mexico, 2010; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Quidiello, J. Atlas de la Historia del Territorio de Andalucía; Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia: Sevilla, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ruta de los Molinos del Ardila. Available online: https://turismo.valenciadelmombuey.com/listado/valencia-del-mombuey/rutas/ruta-de-los-molinos-del-ardila/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- El Molino del Francés de Encinasola. Available online: https://www.huelvainformacion.es/provincia/Molino-Frances-Encinasola_0_1517548613.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Oliva de la Frontera: Ruta Circular Molino de Domiciano. Available online: https://es.wikiloc.com/rutas-senderismo/oliva-de-la-frontera-ruta-circular-molino-de-domiciano-10387701 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

| Municipality | Country | Region | Province/ District | Surface (km2) | Population (inh.) | Population Density (inh./km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encinasola | Spain | Andalucía | Huelva | 178.12 | 1294 | 7.49 |

| Jerez de los Caballeros | Spain | Extremadura | Badajoz | 739.8 | 9147 | 12.36 |

| Oliva de la Frontera | Spain | Extremadura | Badajoz | 149.3 | 4936 | 35.2 |

| Valencia del Mombuey | Spain | Extremadura | Badajoz | 75 | 713 | 9.96 |

| Moura | Portugal | Alentejo | Évora | 957.73 | 13,259 | 13.84 |

| Barrancos | Portugal | Alentejo | Beja | 168.43 | 1697 | 10.07 |

| Mourão | Portugal | Alentejo | Beja | 278.54 | 2351 | 8.44 |

| TOTAL Spain | 402.42 | 6943 | 17.25 | |||

| TOTAL Portugal | 1404.7 | 17,307 | 12.3 | |||

| TOTAL Work Zone | 1807.12 | 24,250 | 13.41 |

| Portugal | Spain | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Extremadura | Andalusia | ||

| Law | Law 107/2001, of 8 September 2001, on the Bases of the Policy and Rules for the Protection and Valorization of Cultural Heritage. | Law 2/1999, of 29 March 1999, on the Historical and Cultural Heritage of Extremadura. | Law 1/1991, of 3 July 1991, on the Historical Heritage of Andalusia. |

| Figures | National Monument (MN: national monument) Property of public interest (IIP: Property of public interest, MIP: Monument of public interest, CIP: Complex of public interest, SIP: Site of public interest). Property of municipal interest (IM: Property of municipal interest, MIM: Monument of municipal interest, CIM: Complex of municipal interest, SIM: Site of municipal interest). | Historic Sites, Archaeological Protection Areas, Historic Gardens, Sites of Ethnological Interest, Monuments, Archaeological Park, Historic Site, Archaeological Zones, and Paleontological Zones. | Historic Site, Historic Gardens, Site of Ethnological Interest, Site of Industrial Interest, Monuments, Historic Site, Archaeological Areas, and Heritage Areas. |

| Municipality | Production | Industrial |

|---|---|---|

| Encinasola | wheat, barley and oats; the imported products are wine, oil and vegetables; there are sheep, goats, pigs and cattle, half of which are used for farming and hunting rabbits, partridges, hares, wild boars, and deer. | The general activity is agriculture; muleteering and women weaving linen and cloth for domestic use. |

| Jerez de los Caballeros | Wheat, barley, rye, oats, vegetables, fruits, wine, oil and acorns; sows, cattle, sheep, goats, working and pack horses, beehives, big and small game, abundant fish and tench fishing. | There are 7 leather tanning factories; 3 of wax and tallow candles; 8 of soft soap; 4 of pottery; 20 looms of canvas, tow and wool blankets; 9 oil mills; 2 presses; 40 flour mills, several tile and brick ovens, 13 stores, fair in the first 8 days of September, of esparto grass and cattle. |

| Oliva de la Frontera | wheat, barley, oats, chickpeas, beans, oil, oranges, fruits (melons and watermelons); sows, cattle, goats, sheep and horses; game of all kinds and fish from the river. | linen and wool looms, run by women; 20 flour mills; wheat is imported, and a modern concession fair is held on September 16 (sows and cattle). |

| Valencia del Mombuey | wheat, rye, barley, oats, chickpeas, beans, wine and acorns; sows, cattle, sheep and mares, and game of all kinds. | 4 brandy factories, homemade linen looms, 4 flour mills, 4 bakeries, and the pig trade. |

| Moura | It abounds in grains, cattle, some wine, and a lot of oil. They have olive groves on the east and south and the rest is occupied by large oak and cork oak forests where they raise a lot of sow cattle; many beehives, abundant hunting. | - |

| Barrancos | - | - |

| Mourão | It produces many grains, oil, wine, cattle, beehives; hunting and fishing of the Guadiana River. | - |

| Municipality | |

|---|---|

| Encinasola | French Mill |

| Mill (d) | |

| Mill (g) | |

| Jerez de los Caballeros | Casabaya Mill |

| Cigarrilla Mill | |

| Fonseca Mill | |

| Las Monjas Mill | |

| Mill (a) | |

| Monsalve Mill | |

| Nicolas Pernales Mill | |

| Cascal Mill | |

| Oliva de la Frontera | Domitian Mill |

| Mill (e) | |

| Mill (f) | |

| Dos Piedras Mill (a) | |

| Valencia del Mombuey | La Junta Mill |

| Dos Piedras Mill (b) | |

| Moura | Santa Marina Mill |

| Mill (b) | |

| Mill (c) | |

| Barrancos | La Pipa Mill |

| Mourão | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arana, A.M.; Pérez Cano, M.T. Agricultural and Industrial Heritage as a Resource in Frontier Territories: The Border Between the Regions of Andalusia–Extremadura (Spain) and Alentejo (Portugal). Agriculture 2025, 15, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15090956

Arana AM, Pérez Cano MT. Agricultural and Industrial Heritage as a Resource in Frontier Territories: The Border Between the Regions of Andalusia–Extremadura (Spain) and Alentejo (Portugal). Agriculture. 2025; 15(9):956. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15090956

Chicago/Turabian StyleArana, Ainhoa Maruri, and María Teresa Pérez Cano. 2025. "Agricultural and Industrial Heritage as a Resource in Frontier Territories: The Border Between the Regions of Andalusia–Extremadura (Spain) and Alentejo (Portugal)" Agriculture 15, no. 9: 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15090956

APA StyleArana, A. M., & Pérez Cano, M. T. (2025). Agricultural and Industrial Heritage as a Resource in Frontier Territories: The Border Between the Regions of Andalusia–Extremadura (Spain) and Alentejo (Portugal). Agriculture, 15(9), 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15090956