Experienced Burden of and Adherence to Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment in Persons with Affective Disorders

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

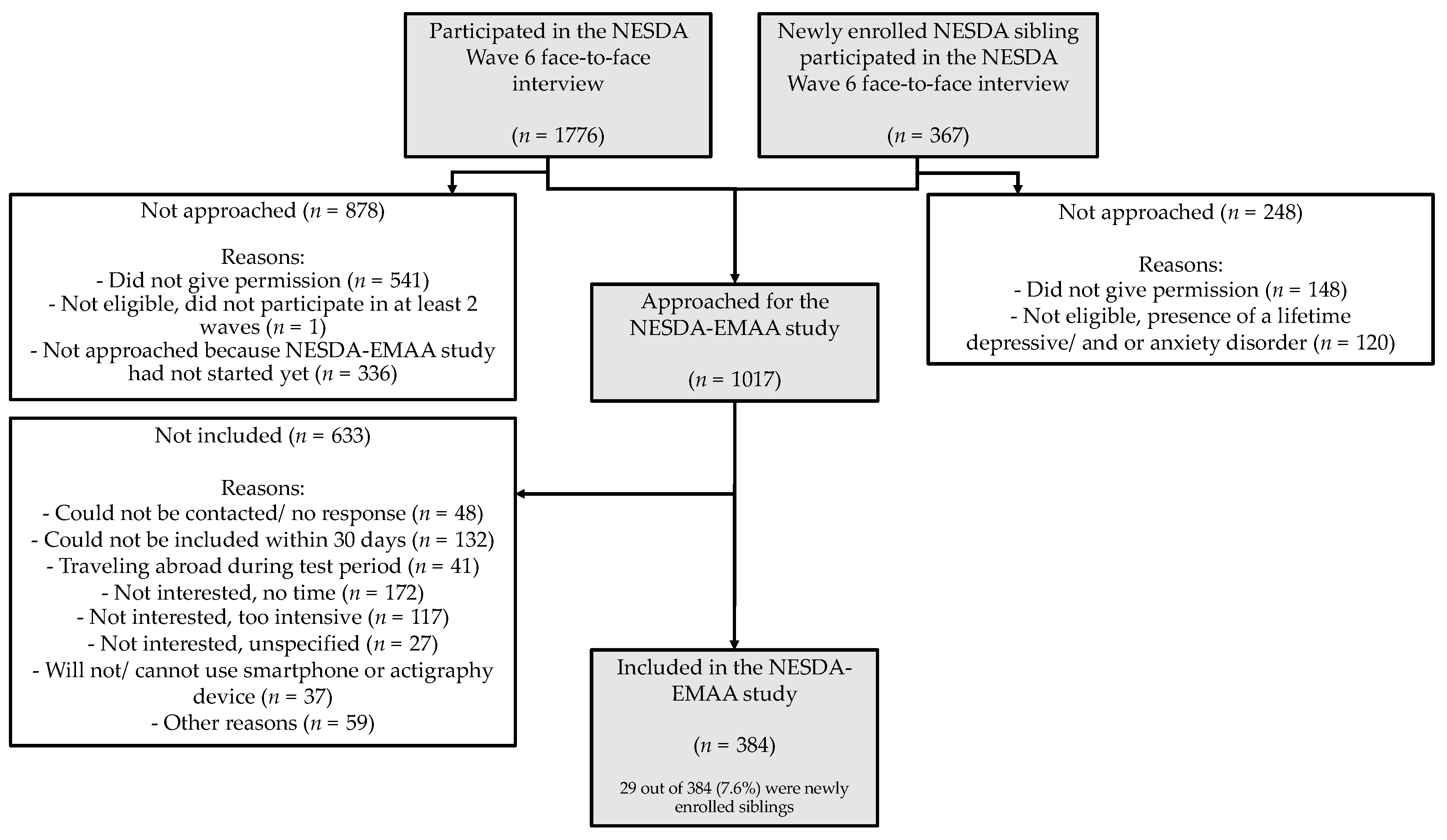

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment Protocol

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Baseline Characteristics

2.3.2. Momentary Affective States

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Momentary Burden

2.4.2. Experienced Burden Over the Whole Monitoring Period

2.4.3. Adherence to the Daily EMA Questionnaires

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

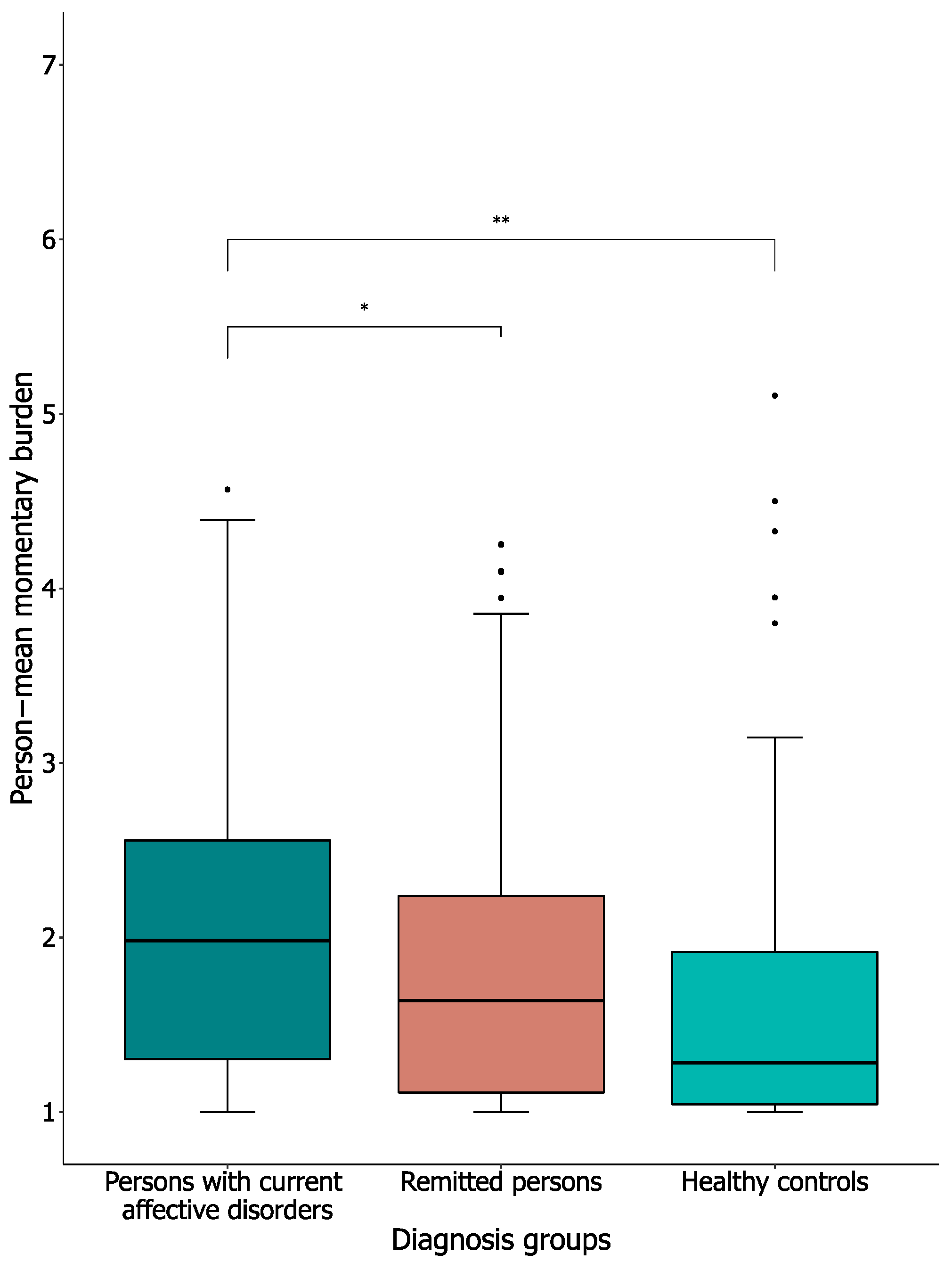

3.2. Burden

3.2.1. Person-Mean Momentary Burden

3.2.2. Association Between Affective States and Momentary Burden

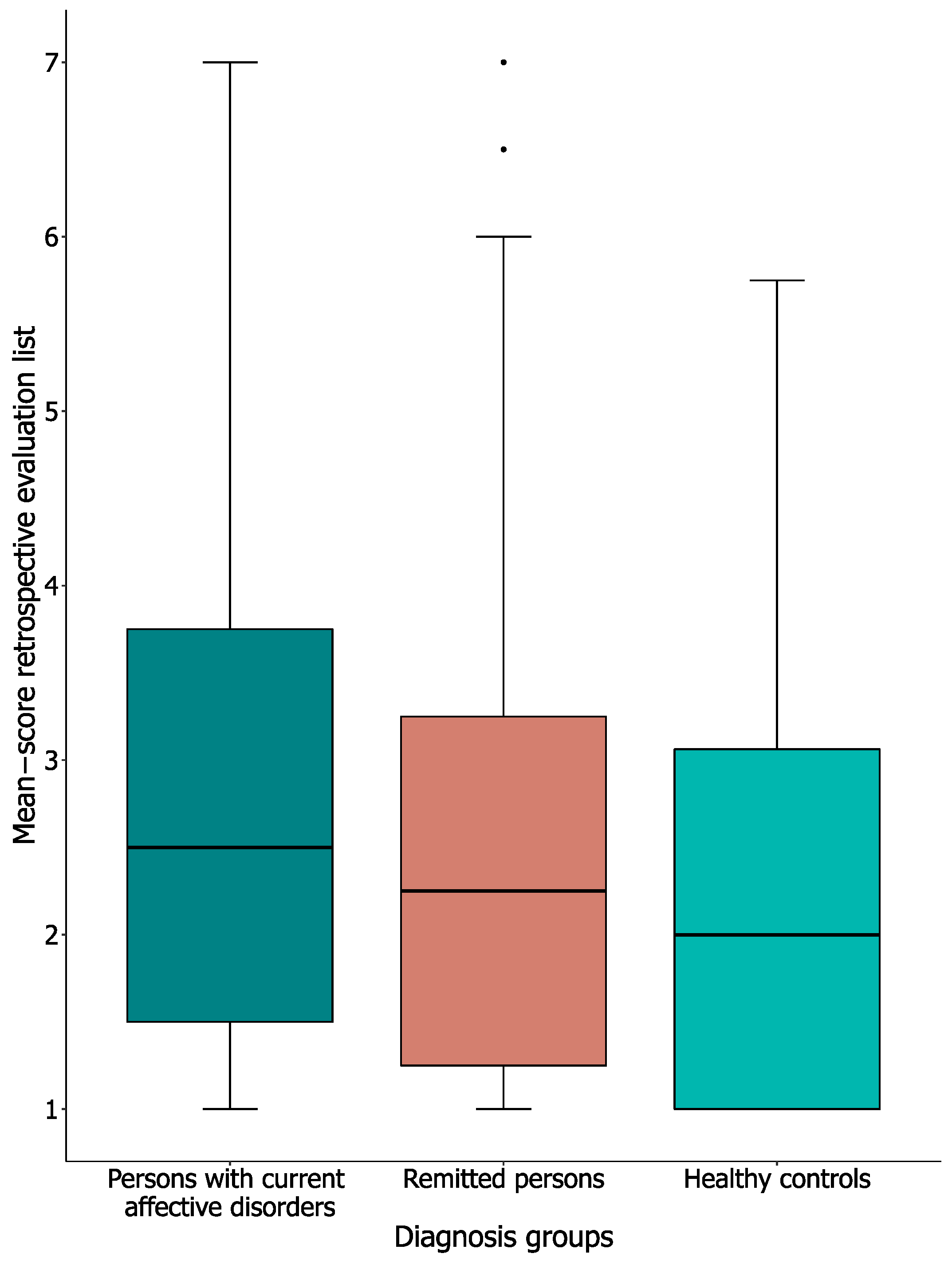

3.2.3. Experienced Burden Over Whole Monitoring Period

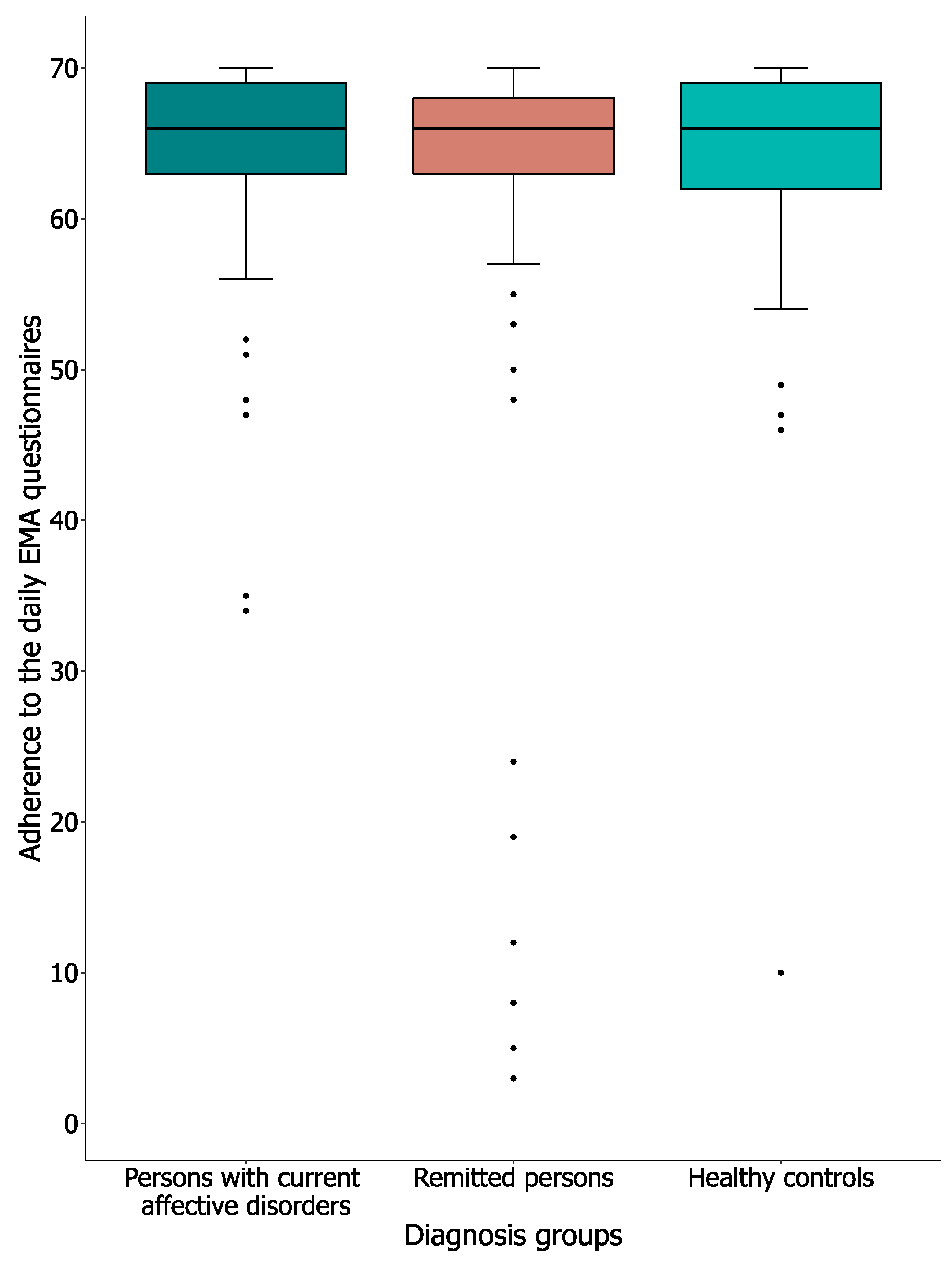

3.3.1. Adherence Rates

3.3.2. Reasons for Missing Daily EMA Questionnaires

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Houben, M.; van den Noortgate, W.; Kuppens, P. The Relation between Short-Term Emotion Dynamics and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 901–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, L.; Swendsen, J.; Cui, L.; Husky, M.; Johns, J.; Zipunnikov, V.; Merikangas, K.R. Mood Reactivity and Affective Dynamics in Mood and Anxiety Disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.; Klumparendt, A.; Doebler, P.; Ehring, T. Everyday Emotional Dynamics in Major Depression. Emotion 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.J.; Mata, J.; Jaeggi, S.M.; Buschkuehl, M.; Jonides, J.; Gotlib, I.H. The everyday emotional experience of adults with major depressive disorder: Examining emotional instability, inertia, and reactivity. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2012, 121, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, L.; Bardill, A.; Fields, B.; Herd, K.; Veale, D.; Grey, N.; Moran, P. The Application of MHealth to Mental Health: Opportunities and Challenges. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myin-Germeys, I.; Kasanova, Z.; Vaessen, T.; Vachon, H.; Kirtley, O.; Viechtbauer, W.; Reininghaus, U. Experience Sampling Methodology in Mental Health Research: New Insights and Technical Developments. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trull, T.J.; Ebner-Priemer, U.W. Using Experience Sampling Methods/Ecological Momentary Assessment (ESM/EMA) in Clinical Assessment and Clinical Research: Introduction to the Special Section. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenze, S.J.; Miller, I.W. Use of Ecological Momentary Assessment in Mood Disorders Research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological Momentary Assessment. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zeev, D.; Young, M.A.; Madsen, J.W. Retrospective Recall of Affect in Clinically Depressed Individuals and Controls. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, A.T.; Miché, M.; Wersebe, H.; Mikoteit, T.; Hoyer, J.; Imboden, C.; Bader, K.; Meyer, A.H.; Hatzinger, M.; Lieb, R. Daily Fluctuation of Emotions and Memories Thereof: Design and Methods of an Experience Sampling Study of Major Depression, Social Phobia, and Controls. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myin-Germeys, I.; Oorschot, M.; Collip, D.; Lataster, J.; Delespaul, P.; van Os, J. Experience Sampling Research in Psychopathology: Opening the Black Box of Daily Life. Psychol. Med. 2009, 39, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armey, M.F.; Schatten, H.T.; Haradhvala, N.; Miller, I.W. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) of depression-related phenomena. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 4, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aan het Rot, M.; Hogenelst, K.; Schoevers, R.A. Mood Disorders in Everyday Life: A Systematic Review of Experience Sampling and Ecological Momentary Assessment Studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, D.; Fernández-Álvarez, J.; Patané, A.; Semonella, M.; Kwiatkowska, M.; García-Palacios, A.; Cipresso, P.; Riva, G.; Botella, C. Current State and Future Directions of Technology-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention for Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, L.C.; Nauta, M.H.; Aan Het Rot, M. Experience Sampling and Ecological Momentary Assessment for Studying the Daily Lives of Patients with Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Alford, B.A. Depression: Causes and Treatment, 2nd ed.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Difrancesco, S.; Lamers, F.; Riese, H.; Merikangas, K.R.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Hemert, A.M.; Schoevers, R.A.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Sleep, Circadian Rhythm, and Physical Activity Patterns in Depressive and Anxiety Disorders: A 2-week Ambulatory Assessment Study. Depress. Anxiety 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoevers, R.A.; Van Borkulo, C.D.; Lamers, F.; Servaas, M.N.; Bastiaansen, J.A.C.J.; Beekman, A.T.; Van Hemert, A.M.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Riese, H. Momentary affect fluctuations differ between patients with current depression and anxiety disorders, remitters and healthy controls. Psychol. Med. (under review).

- Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.; Smit, J.H.; Zitman, F.G.; Nolen, W.A.; Spinhoven, P.; Cuijpers, P.; De Jong, P.J.; Van Marwijk, H.W.; Assendelft, W.J.; et al. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): Rationale, Objectives and Methods. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytema, S.; van der Krieke, L. Routine Outcome Monitoring: A Tool to Improve the Quality of Mental Health Care. In Improving Mental Health Care: The Global Challenge, 1st ed.; Thornicroft, G., Ruggeri, M., Goldberg, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmans, C.; De Jong, K.; Timman, R.; Zijlstra-Vlasveld, M.; Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C.; Tan, S.S.; Hakkaart-Van Roijen, L. Feasibility, reliability and validity of a questionnaire on healthcare consumption and productivity loss in patients with a psychiatric disorder (TiC-P). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H.U.; Robins, L.N.; Cottler, L.B.; Sartorius, N.; Burke, J.D.; Regier, D. Cross-Cultural Feasibility, Reliability and Sources of Variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Br. J. Psychiatr. 1991, 159, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennik, E. Every Dark Cloud Has a Colored Lining: The Relation between Positive and Negative Affect and Reactivity to Positive and Negative Events. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Preisser, J.S.; Qaqish, B.F.; Suchindran, C.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Wolfson, M. A comparison of two bias-corrected covariance estimators for generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 2007, 63, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twisk, J.; de Vente, W. Attrition in Longitudinal Studies: How to Deal with Missing Data. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2002, 55, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Remmerswaal, D.; Verveer, I.; Robinson, E.; Franken, I.H.A.; Wen, C.K.F.; Field, M. Compliance with Ecological Momentary Assessment Protocols in Substance Users: A Meta-Analysis. Addiction 2018, 114, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, K.A.M.; Bos, E.H.; Rosmalen, J.G.M.; Wichers, M.C.; Riese, H. A Qualitative Approach to Guide Choices for Designing a Diary Study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, F.M.; Snippe, E.; Bruggeman, R.; Wichers, M.; van der Krieke, L. Insights of patients and clinicians on the promise of the experience sampling method for psychiatric care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo Gee, B.; Griffiths, K.M.; Gulliver, A. Effectiveness of Mobile Technologies Delivering Ecological Momentary Interventions for Stress and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueller, S.M.; Aguilera, A.; Mohr, D.C. Ecological Momentary Interventions for Depression and Anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Persons with Current Affective Disorder(S) Persons (n = 100) | Remitted Persons (n = 190) | Healthy Controls (n = 94) | Total (n = 384) | Test Value | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 50.5 (41.5–59.0) | 48.5 (36.0–61.0) | 54.0 (4.0–62.0) | 51.0 (38.0–61.0) | H(2) = 4.25 | 0.12 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 64 (64.0) | 132 (69.5) | 51 (54.3) | 238 (67.0) | χ2(2) = 6.35 | 0.04 | |

| Male | 36 (36.0) | 58 (30.5) | 43 (45.7) | 117 (33.0) | |||

| Educational level | |||||||

| Basic | 8 (8.0) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 13 (3.4) | χ2(4) = 14.51 | 0.01 | |

| Intermediate | 49 (49.0) | 106 (55.8) | 38 (40.4) | 193 (50.3) | |||

| High | 43 (43.0) | 80 (42.1) | 55 (58.5) | 178 (46.4) | |||

| Working hours (a week) | 10.0 (0.0–32.0) | 20.0 (0.0–32.0) | 30.0 (0.0–37.0) | 20.0 (0.0–35.5) | H(2) = 10.22 | 0.01 | |

| DSM-IV-R Diagnosis | Current | Lifetime | |||||

| One more or anxiety disorder | 71(71.0) | 142 (74.7) | |||||

| One or more depressive disorder | 61 (61.0) | 163 (85.8) | |||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 12 (12.0) | 69 (36.3) | |||||

| Social phobia | 35 (35.0) | 86 (45.3) | |||||

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia | 6 (6.0) | 41 (21.6) | |||||

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia | 13 (13.0) | 31 (16.3) | |||||

| Agoraphobia | 22 (22.0) | 32 (16.8) | |||||

| Major depressive disorder | 57 (57.0) | 160 (84.2) | |||||

| Dysthymia | 15 (15.0) | 52 (27.4) | |||||

| Number of affective disorders* | Current | Lifetime | |||||

| 1 | 61 (61.0) | 64 (33.7) | |||||

| 2 | 23 (23.0) | 45 (23.7) | |||||

| 3 | 12 (12.0) | 39 (20.5) | |||||

| 4 | 3 (3.0) | 22 (11.6) | |||||

| 5 | 1 (1.0) | 10 (5.3) | |||||

| 6 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.2) | |||||

| 7 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | |||||

| Regression Coefficient (Standard Error) | 95%CI | Test Value | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect and momentary burden | |||||

| Positive affect (PA) * | −0.23 (0.02) | −0.27–0.19 | χ2(1) = 130.77 | <0.0001 | |

| + diagnosis groups | −0.22 (0.02) | −0.26–0.18 | χ2(1) = 114.36 | <0.0001 | |

| + weekly working hours | −0.23 (0.02) | −0.27–0.19 | χ2(1) = 133.58 | <0.0001 | |

| + gender | −0.23 (0.02) | −0.27–0.19 | χ2(1) = 131.38 | <0.0001 | |

| + age | −0.23 (0.02) | −0.27–0.19 | χ2(1) = 120.83 | <0.0001 | |

| + educational level | −0.23 (0.02) | −0.27–0.19 | χ2(1) = 134.67 | <0.0001 | |

| + PA × diagnosis groups | |||||

| Persons with current affective disorders | |||||

| Remitted persons † | 0.00 (0.05) | −0.09–0.10 | χ2(1) = 0.01 | 0.92 | |

| Healthy controls † | −0.00 (0.07) | −0.13–0.13 | χ2(1) = 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| + PA × weekly working hours | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00–0.00 | χ2(1) = 0.23 | 0.63 | |

| + PA × gender ‡ | −0.09 (0.04) | −0.17–0.00 | χ2(1) = 3.77 | 0.05 | |

| + PA × age | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00–0.00 | χ2(1) = 0.31 | 0.58 | |

| + PA × educational level | |||||

| Low | |||||

| Moderate § | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.22–0.08 | χ2(1) = 0.90 | 0.34 | |

| High § | −0.13 (0.07) | −0.28–0.02 | χ2(1) = 3.11 | 0.08 | |

| Negative affect and momentary burden | |||||

| Negative affect (NA) * | 0.30 (0.03) | 0.24–0.37 | χ2(1) = 80.53 | <0.0001 | |

| + diagnosis groups | 0.29 (0.03) | 0.22–0.36 | χ2(1) = 73.09 | <0.0001 | |

| + weekly working hours | 0.31 (0.03) | 0.24–0.38 | χ2(1) = 83.94 | <0.0001 | |

| + gender | 0.31 (0.03) | 0.24–0.37 | χ2(1) = 81.76 | <0.0001 | |

| + age | 0.30 (0.03) | 0.23–0.37 | χ2(1) = 73.79 | <0.0001 | |

| + educational level | 0.32 (0.03) | 0.25–0.38 | χ2(1) = 90.22 | <0.0001 | |

| + NA × diagnosis groups | |||||

| Persons with current affective disorders | |||||

| Remitted persons † | 0.05 (0.07) | −0.09–0.19 | χ2(1) = 0.48 | 0.49 | |

| Healthy controls † | 0.09 (0.13) | −0.15–0.40 | χ2(1) = 0.54 | 0.46 | |

| + NA × weekly working hours | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.01–0.00 | χ2(1) = 1.09 | 0.30 | |

| + NA × gender ‡ | 0.04 (0.07) | −0.10–0.18 | χ2(1) = 0.33 | 0.57 | |

| + NA × age | 0.01 (0.00) | −0.00–0.01 | χ2(1) = 3.77 | 0.05 | |

| + NA × educational level | |||||

| Low | |||||

| Moderate § | 0.15 (0.14) | −0.12–0.42 | χ2(1) = 1.14 | 0.29 | |

| High § | 0.21 (0.14) | −0.06–0.49 | χ2(1) = 2.28 | 0.13 | |

| Stability of momentary burden | |||||

| Time● | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00–0.00 | χ2(1) = 2.83 | 0.09 | |

| Persons with Current Affective Disorders (n = 77) | Remitted Persons (n = 156) | Healthy Controls (n = 75) | Total (n = 321) | Test Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of reasons | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1-3) | H(2) = 3.10 | 0.21 |

| Main reasons for missing questionnaires | ||||||

| Being busy with an activity | 52 (67.5) | 86 (55.1) | 46 (61.3) | 184 (57.3) | χ2(2) = 3.40 | 0.18 |

| No network connection | 18 (23.4) | 38 (24.4) | 16 (21.3) | 72 (22.4) | χ2(2) = 0.26 | 0.88 |

| Being asleep | 22 (28.6) | 36 (23.1) | 10 (13.3) | 68 (21.2) | χ2(2) = 5.31 | 0.07 |

| Technical problems | 14 (18.2) | 29 (18.6) | 15 (20.0) | 58 (18.1) | χ2(2) = 0.94 | 0.95 |

| Did not hear the smartphone | 17 (22.1) | 24 (15.4) | 14 (18.7) | 55 (17.1) | χ2(2) = 1.62 | 0.45 |

| Did not bring the smartphone | 12 (15.6) | 26 (16.7) | 7 (9.3) | 45 (14.0) | χ2(2) = 2.26 | 0.32 |

| Could not make themselves do it | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | χ2(2) = 3.01 | 0.22 |

| Other reason | 15 (19.5) | 40 (25.6) | 18 (24.0) | 73 (22.7) | χ2(2) = 1.09 | 0.58 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Genugten, C.R.; Schuurmans, J.; Lamers, F.; Riese, H.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Schoevers, R.A.; Riper, H.M.; Smit, J.H. Experienced Burden of and Adherence to Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment in Persons with Affective Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020322

van Genugten CR, Schuurmans J, Lamers F, Riese H, Penninx BWJH, Schoevers RA, Riper HM, Smit JH. Experienced Burden of and Adherence to Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment in Persons with Affective Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(2):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020322

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Genugten, Claire R., Josien Schuurmans, Femke Lamers, Harriëtte Riese, Brenda W. J. H. Penninx, Robert A. Schoevers, Heleen M. Riper, and Johannes H. Smit. 2020. "Experienced Burden of and Adherence to Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment in Persons with Affective Disorders" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 2: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020322

APA Stylevan Genugten, C. R., Schuurmans, J., Lamers, F., Riese, H., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Schoevers, R. A., Riper, H. M., & Smit, J. H. (2020). Experienced Burden of and Adherence to Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment in Persons with Affective Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(2), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020322