Temporal Cardiorenal Dynamics and Mortality Prediction After TAVR: The Prognostic Value of the 48–72 h BUN/EF Ratio

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population, and Data Collection

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Severe aortic stenosis treated with TAVI procedure

- Availability of preprocedural blood urea nitrogen and ejection fraction

- Exclusion criteria included:

- Presence of active malignancy expecting to shorten life expectancy <1-year (with oncological evaluation), active infection, autoimmune disease, or chronic inflammatory conditions

- Missing or incomplete preprocedural laboratory data

2.2. Study Endpoint

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Laboratory Findings

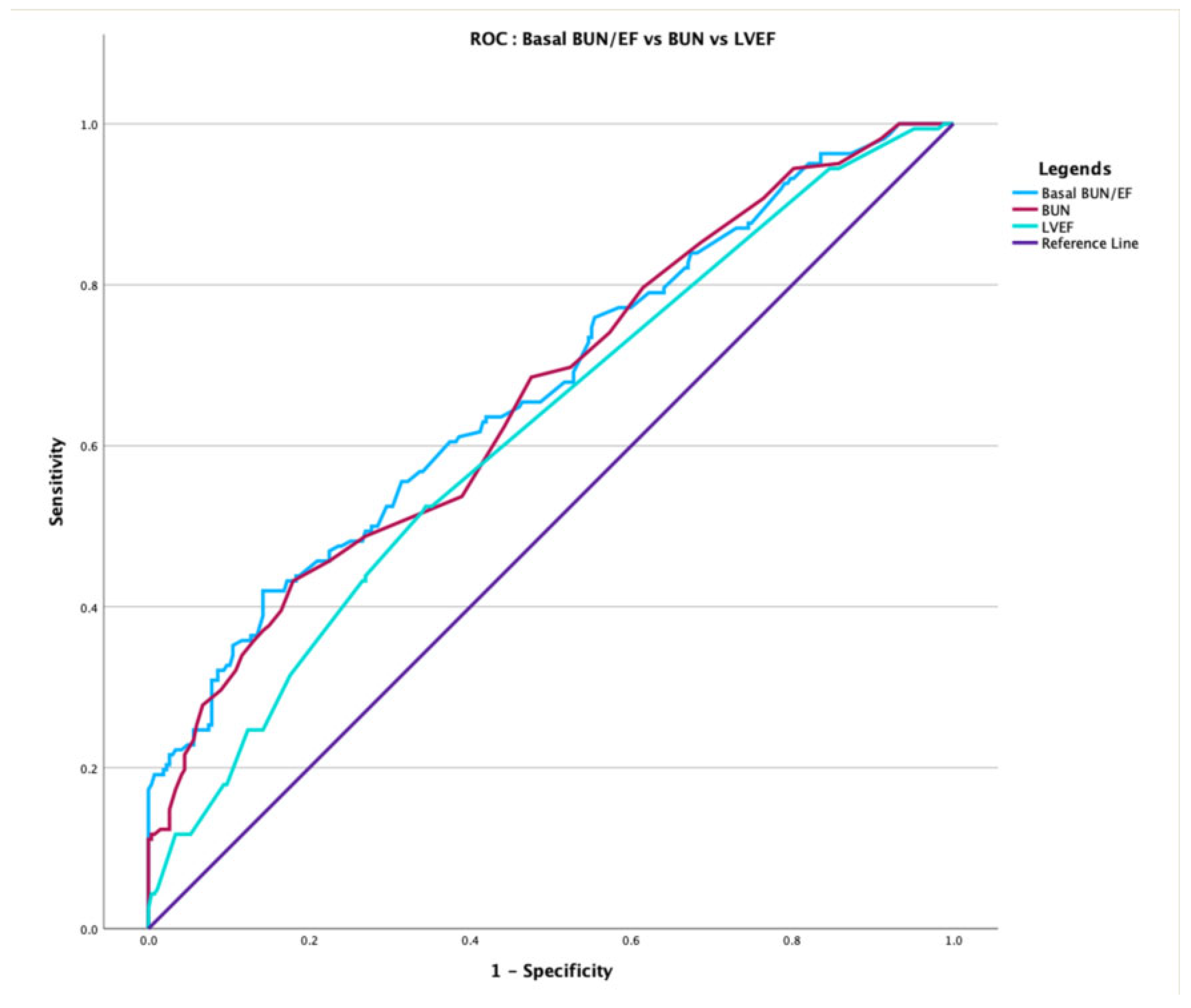

3.2. Prediction of Overall Mortality and Multivariable Analysis

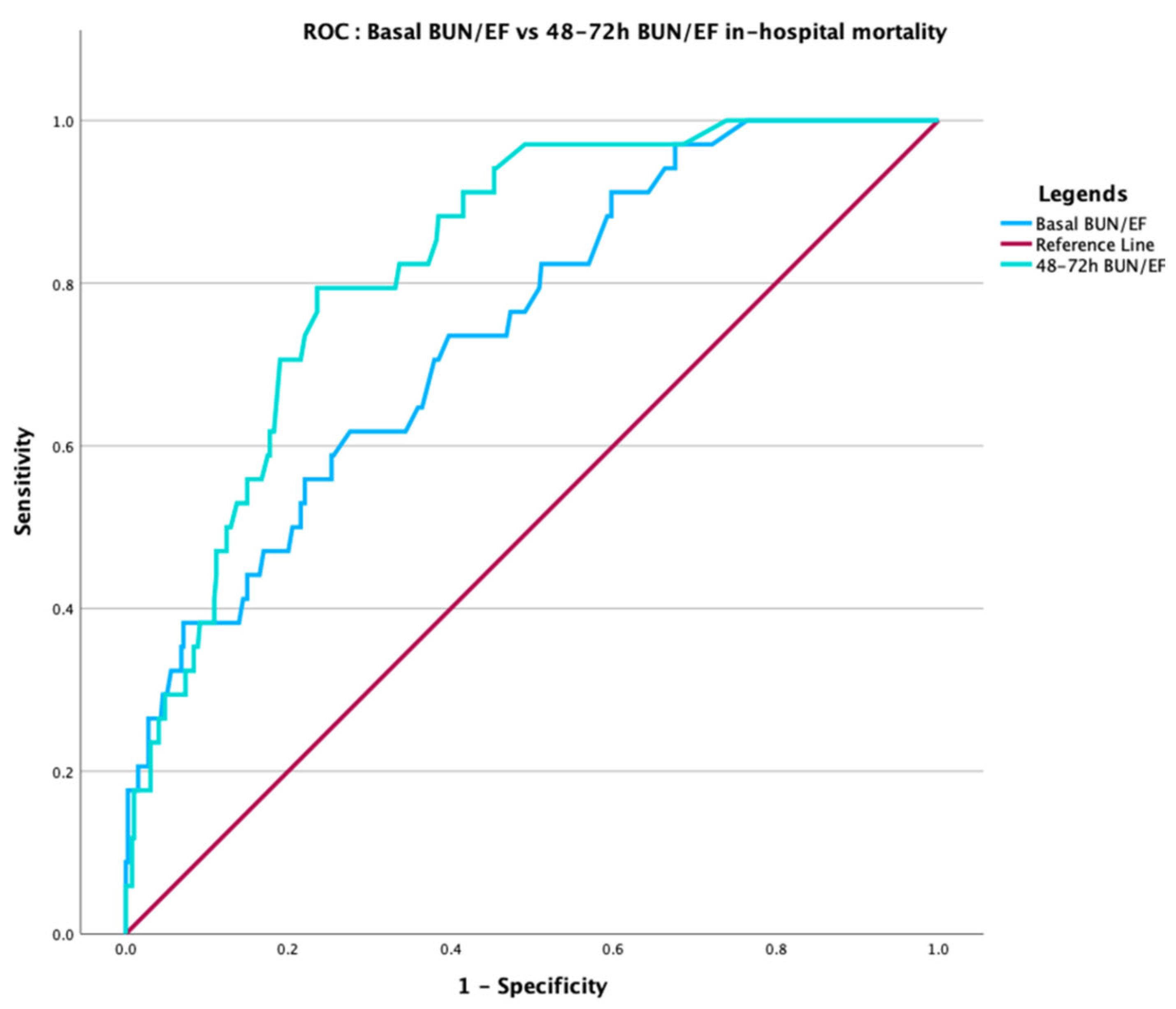

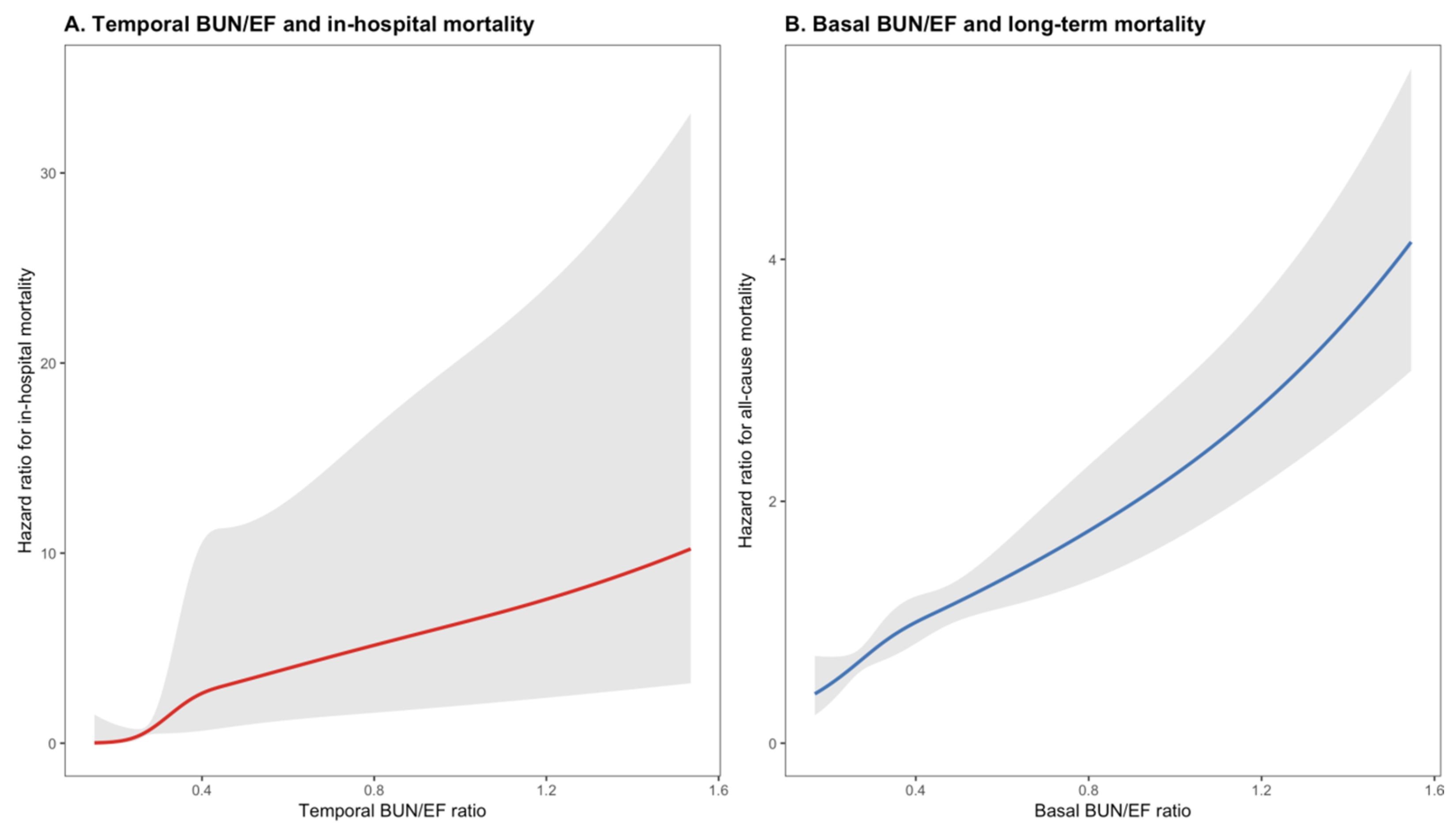

3.3. Temporal Dynamics and Prediction of In-Hospital Mortality

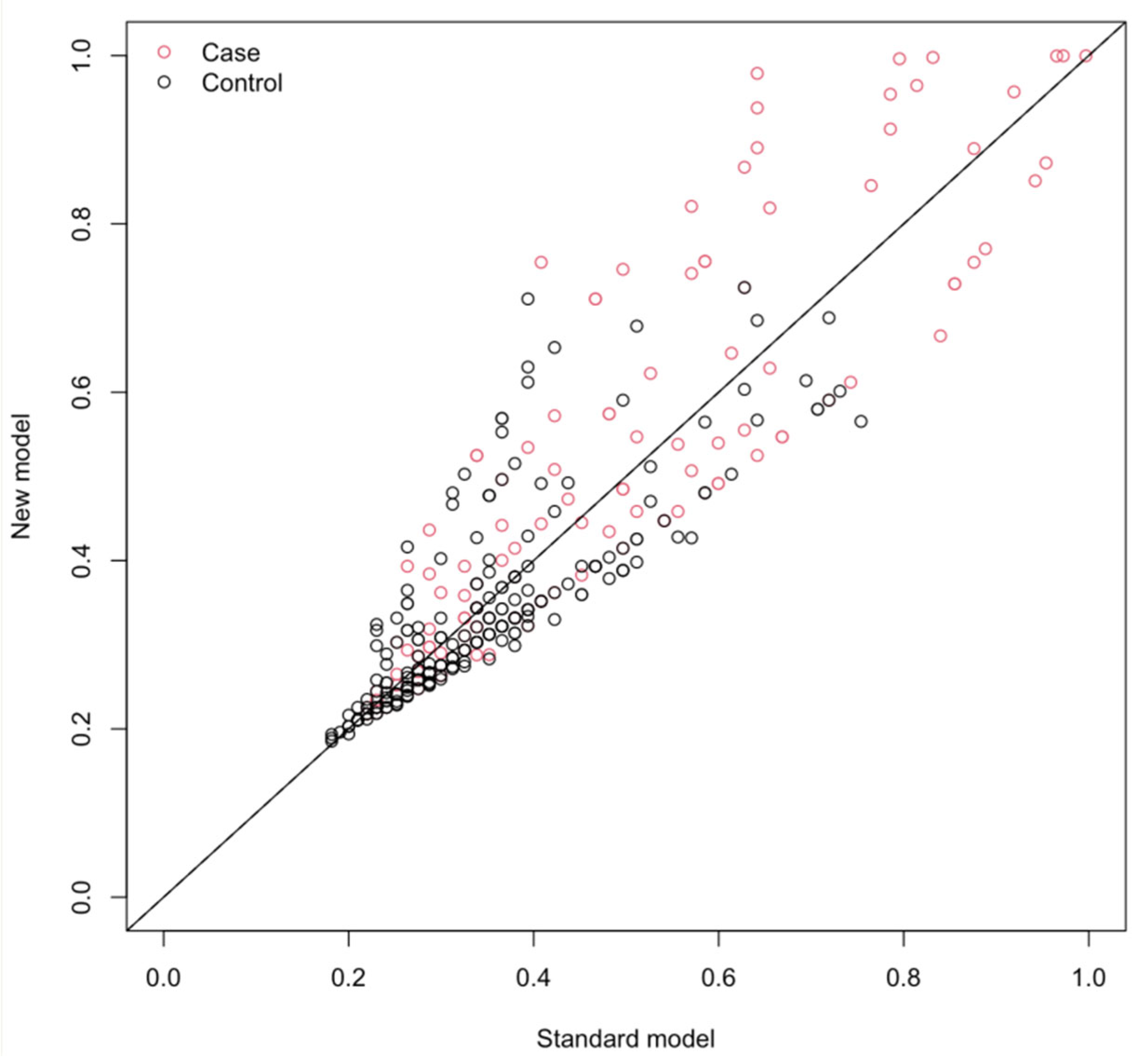

3.4. Comparative Performance and Incremental Value over EuroSCORE II

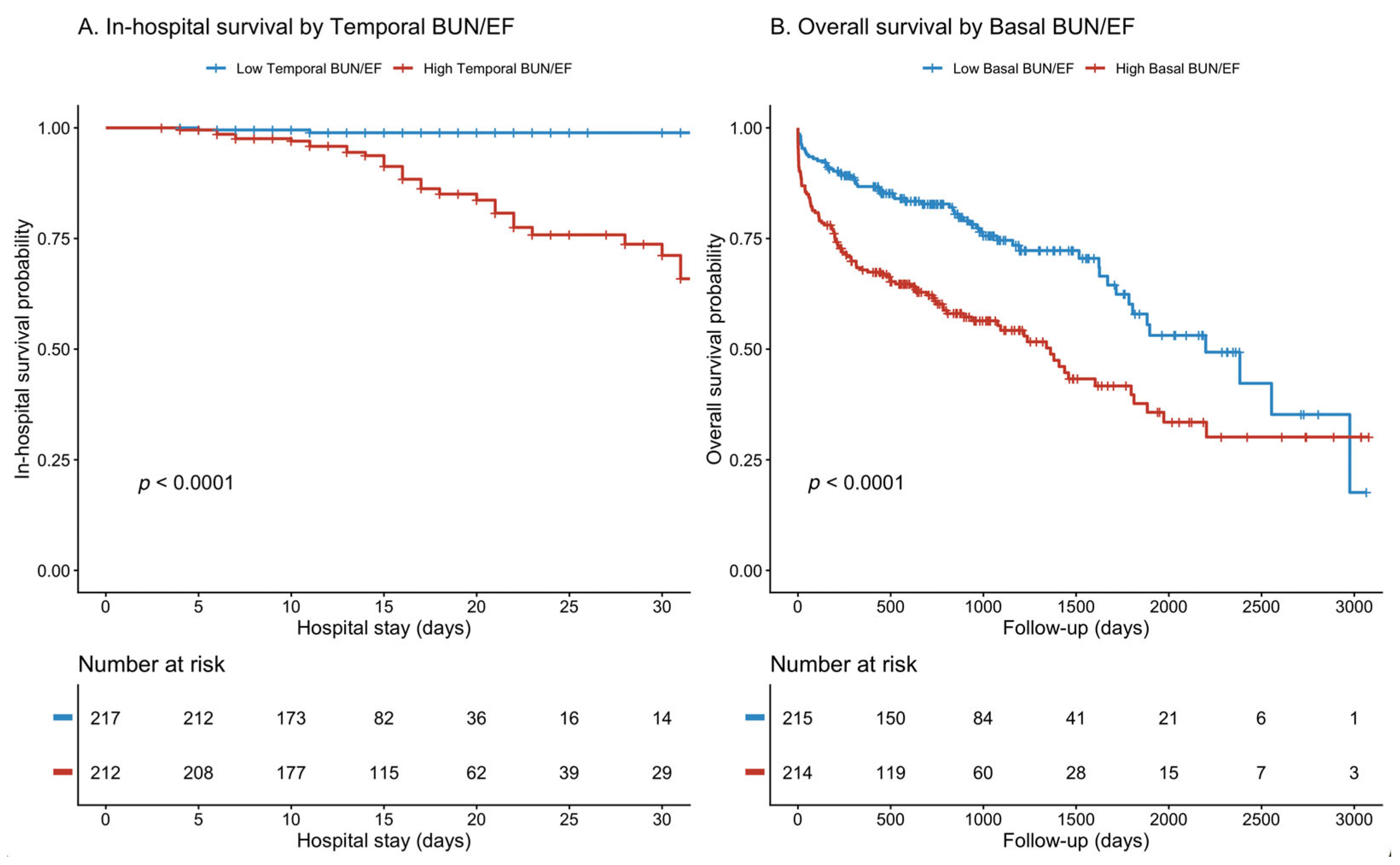

3.5. Mortality Analysis: Early vs. Late Risk Stratification

3.6. Dose–Response Relationship and Clinical Utility

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathophysiological Rationale

4.2. Temporal vs. Baseline Predictive Patterns

4.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindman, B.R.; Clavel, M.A.; Mathieu, P.; Iung, B.; Lancellotti, P.; Otto, C.M.; Pibarot, P. Calcific aortic stenosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genereux, P.; Sharma, R.P.; Cubeddu, R.J.; Aaron, L.; Abdelfattah, O.M.; Koulogiannis, K.P.; Marcoff, L.; Naguib, M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. The Mortality Burden of Untreated Aortic Stenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, M.B.; Smith, C.R.; Mack, M.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjonas, D.; Dahle, G.; Schirmer, H.; Malm, S.; Eidet, J.; Aaberge, L.; Steigen, T.; Aakhus, S.; Busund, R.; Rosner, A. Predictors of early mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Open Heart 2019, 6, e000936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, K.; Saji, M.; Higuchi, R.; Takamisawa, I.; Nanasato, M.; Tamura, H.; Sato, K.; Yokoyama, H.; Doi, S.; Okazaki, S.; et al. Predictors for all-cause mortality in men after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: A report from the LAPLACE-TAVI registry. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2023, 48, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Hayashida, K.; Hengstenberg, C.; Watanabe, Y.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Jin, J.; Saito, S.; Valgimigli, M.; Nicolas, J.; Mehran, R.; et al. Predictors of All-Cause Mortality After Successful Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 207, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiris, T.; Avci, E.; Celik, A. Association of the blood urea nitrogen-to-left ventricular ejection fraction ratio with contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with acute coronary syndrome who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyildiz, A.G.; Kalaycioglu, E.; Ozyildiz, A.; Turan, T.; Cetin, M. Blood urea nitrogen to left ventricular ejection fraction ratio is associated with long-term mortality in the stable angina pectoris patients. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 9250–9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolomeo, P.; Butt, J.H.; Kondo, T.; Campo, G.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Kober, L.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rouleau, J.L.; Solomon, S.D.; et al. Independent prognostic importance of blood urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Luo, S.; Huang, B. Blood Urea Nitrogen to Left Ventricular Ejection Ratio as a Predictor of Short-Term Outcome in Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock. J. Vasc. Res. 2024, 61, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Hung, J.; Bermejo, J.; Chambers, J.B.; Edvardsen, T.; Goldstein, S.; Lancellotti, P.; LeFevre, M.; Miller, F., Jr.; Otto, C.M. Recommendations on the Echocardiographic Assessment of Aortic Valve Stenosis: A Focused Update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Coresh, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Wang, D.; Sang, Y.; Crews, D.C.; Doria, A.; Estrella, M.M.; Froissart, M.; et al. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C-Based Equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattazzi, M.; Bertacco, E.; Del Vecchio, A.; Puato, M.; Faggin, E.; Pauletto, P. Aortic valve calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2968–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, C.; Dohi, K.; Sakurai, Y.; Bessho, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Fujii, S.; Sugimoto, T.; Tanabe, M.; Onishi, K.; Shiraki, K.; et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on the presence and severity of aortic stenosis in patients at high risk for coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2011, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzuoli, A.; Ruocco, G.; Pellegrini, M.; Martini, S.; Del Castillo, G.; Beltrami, M.; Franci, B.; Lucani, B.; Nuti, R. Patients with cardiorenal syndrome revealed increased neurohormonal activity, tubular and myocardial damage compared to heart failure patients with preserved renal function. Cardiorenal Med. 2014, 4, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokmen, A.; Aksu, E.; Aykan, A.; Sokmen, G.; Gunes, H.; Balcioglu, A.; Celik, E.; Ozgul, S. Predictors of mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Ann. Med. Res. 2020, 27, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, D.; Chernin, G.; Meledin, V.; Zikry, M.; Shuvy, M.; Gandelman, G.; Goland, S.; George, J.; Shimoni, S. Urea level is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokalski, V.; Liu, D.; Hu, K.; Frantz, S.; Nordbeck, P. Echocardiographic predictors of outcome in severe aortic stenosis patients with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauerman, H.L.; Reardon, M.J.; Popma, J.J.; Little, S.H.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Adams, D.H.; Kleiman, N.S.; Oh, J.K. Early Recovery of Left Ventricular Systolic Function After CoreValve Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, e003425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicaslan, B.; Unal, B.; Arslan, B.; Ekin, T.; Ozel, E.; Ertas, F.; Dursun, H.; Ozdogan, O. Impact of the recovery of left ventricular ejection fraction after TAVI on mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. Turk. Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2021, 49, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.Q.; Zeng, C.L. Blood Urea Nitrogen and In-Hospital Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Cardiogenic Shock: Analysis of the MIMIC-III Database. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5948636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, D.; Mittleman, M.A.; Burger, A.J. Elevated blood urea nitrogen level as a predictor of mortality in patients admitted for decompensated heart failure. Am. J. Med. 2004, 116, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cheang, I.; Liao, S.; Wang, K.; Yao, W.; Yin, T.; Lu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Blood Urea Nitrogen to Creatinine Ratio and Long-Term Mortality in Patients with Acute Heart Failure: A Prospective Cohort Study and Meta-Analysis. Cardiorenal Med. 2020, 10, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Rigamonti, E.; Lombardo, M. Incremental prognostic role of left atrial reservoir strain in asymptomatic patients with moderate aortic stenosis. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 37, 1913–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassen, J.; Pio, S.M.; Ewe, S.H.; Singh, G.K.; Hirasawa, K.; Butcher, S.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Genereux, P.; Leon, M.B.; Marsan, N.A.; et al. Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain in Patients with Moderate Aortic Stenosis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 791–800.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, V.E.; Lopes, A.S.; Accorsi, T.A.; Fernandes, J.R.; Spina, G.S.; Sampaio, R.O.; Paixao, M.R.; Pomerantzeff, P.M.; Lemos Neto, P.A.; Tarasoutchi, F. EuroSCORE II and STS as mortality predictors in patients undergoing TAVI. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2016, 62, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; Cicoira, M.; McCullough, P.A. Cardiorenal syndrome type 1: Pathophysiological crosstalk leading to combined heart and kidney dysfunction in the setting of acutely decompensated heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, P.A.; Amin, A.; Pantalone, K.M.; Ronco, C. Cardiorenal Nexus: A Review with Focus on Combined Chronic Heart and Kidney Failure, and Insights From Recent Clinical Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics (n, %) | Survived (n = 267) | Non—Survived (n = 162) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.19 ± 7.69 | 78.33 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Gender (Male) | 129 (48.3%) | 83 (51.2%) | 0.558 |

| DM | 90 (33.7%) | 56 (34.6%) | 0.855 |

| HT | 186 (69.7%) | 100 (61.7%) | 0.091 |

| Dyslipidemia | 99 (37.1%) | 47 (29%) | 0.087 |

| Carotid Artery Disease | 5 (1.9%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.610 |

| Smoking | 11 (4.1%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0.367 |

| CAD | 217 (81.2%) | 135 (83.3%) | 0.474 |

| History of Heart Valve Surgery | 9 (3.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.182 |

| PAD | 29 (10.9%) | 29 (17.9%) | 0.039 |

| Heart Failure | 68 (25.5%) | 46 (28.4%) | 0.506 |

| COPD | 18 (6.7%) | 20 (12.3%) | 0.048 |

| Previous Stroke | 20 (7.5%) | 11 (6.8%) | 0.786 |

| CKD n (%) | 52 (19.5%) | 58 (35.8%) | <0.001 |

| Previous AF | 63 (23.6%) | 48 (29.6%) | 0.167 |

| PCI Before TAVI | 23 (8.6%) | 20 (12.3%) | 0.212 |

| LVEF (%) | 55.53 ± 9.76 | 50.90 ± 11.92 | <0.001 |

| EUROSCORE 2 † | 10.25 (8.53–12.43) | 12.79 (9.88–18.61) | <0.001 |

| Discharge Medications | |||

| Antiplatelet therapy | 257 (96.3%) | 137 (84.6) | <0.001 |

| VKAs | 25 (9.4%) | 11 (6.8) | 0.351 |

| DOACs | 39 (14.6%) | 18 (11.1%) | 0.301 |

| Beta-blockers | 144 (53.9%) | 90 (55.6%) | 0.743 |

| ACEIs/ARBs | 103 (38.6%) | 41 (25.3%) | 0.005 |

| SGLT2i | 8 (3%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0.748 |

| Diuretics | 61 (22.8%) | 57 (35.2%) | 0.006 |

| MRAs | 27 (10.1%) | 13 (8%) | 0.471 |

| Statins | 210 (78.7%) | 77 (47.5%) | <0.001 |

| Parameters | Survived (n = 267) | Non-Survived (n = 162) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HGB (g/dL) | 11.24 ± 1.72 | 10.83 ± 2.01 | 0.023 |

| Lymphocyte (×103/μL) † | 1.40 (1.0–1.7) | 1.20 (0.89–1.70) | 0.027 |

| WBC (×103/μL) | 8.05 ± 3.38 | 8.22 ± 3.18 | 0.626 |

| PLT (×103/μL) | 220.92 ± 81.46 | 214.38 ± 86.29 | 0.431 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.52 ± 0.50 | 3.31 ± 0.52 | <0.001 |

| GFR (mL/min) | 67.98 ± 17.68 | 59.26 ± 21.98 | <0.001 |

| Cre (mg/dL) † | 1 (0.85–1.19) | 1.12 (0.91–1.44) | <0.001 |

| 48–72 h Cre (mg/dL) † | 0.98 (0.78–1.19) | 1.12 (0.83–1.76) | <0.001 |

| BUN † | 19 (15–24) | 23 (17–38) | <0.001 |

| 48–72 h BUN † | 16 (13–22) | 24.5 (16–37) | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) † | 17 (5.95–55.35) | 22 (10–55) | 0.398 |

| BUN/EF Ratio † | 0.35 (0.26–0.48) | 0.45 (0.32–0.80) | <0.001 |

| 48–72 h BUN/EF Ratio † | 0.28 (0.23–0.44) | 0.54 (0.32–0.73) | <0.001 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.055 | 1.027–1.084 | <0.001 | 1.055 | 1.021–1.091 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.702 | 0.466–1.059 | 0.092 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.694 | 0.455–1.056 | 0.088 | |||

| PAD | 1.789 | 1.026–3.123 | 0.040 | |||

| COPD | 1.948 | 0.998–3.805 | 0.051 | |||

| Albumin | 0.921 | 0.881–0.962 | <0.001 | 0.928 | 0.885–0.974 | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.882 | 0.791–0.984 | 0.025 | |||

| GFR | 0.978 | 0.968–0.988 | <0.001 | |||

| BUN ‡ | 1.061 | 1.041–1.083 | <0.001 | |||

| EF ‡ | 0.962 | 0.944–0.980 | <0.001 | |||

| BUN/EF | 14.396 | 6.064–34.172 | <0.001 | 18.328 | 7.004–47.963 | <0.001 |

| BUN/EF † | 3.117 | 2.156–4.505 | <0.001 | 3.455 | 2.293–5.206 | <0.001 |

| AUC | ΔAUC (p) | NRI | IDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (Model 1) | 0.662 | reference | – | – |

| BUN/EF (Model 2) | 0.672 | 0.397 | +0.210 | +0.021 (p = 0.018) |

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | Concordance | AUC (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48–72 h BUN/EF | 3.79 (2.45–5.86) | <0.001 | 0.778 | 0.826 (p = 0.007) |

| Basal BUN/EF | – | – | – | 0.743 |

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | Concordance | AUC (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal BUN/EF | 3.61 (2.84–4.58) | <0.001 | 0.674 | |

| 48–72 h BUN/EF | – | – | – | 0.720 (p = 0.019) |

| AUC | ΔAUC (p) | NRI | IDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EuroSCORE II (Model 1) | 0.668 | reference | – | – |

| EuroSCORE II + BUN/EF (Model 2) | 0.712 | 0.044 | +0.330 | +0.067 (p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Çelik, A.; Kırış, T.; Kayaaltı Esin, F.; Babacan, S.; Erdem, H.; Karaca, M. Temporal Cardiorenal Dynamics and Mortality Prediction After TAVR: The Prognostic Value of the 48–72 h BUN/EF Ratio. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020676

Çelik A, Kırış T, Kayaaltı Esin F, Babacan S, Erdem H, Karaca M. Temporal Cardiorenal Dynamics and Mortality Prediction After TAVR: The Prognostic Value of the 48–72 h BUN/EF Ratio. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020676

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇelik, Aykan, Tuncay Kırış, Fatma Kayaaltı Esin, Semih Babacan, Harun Erdem, and Mustafa Karaca. 2026. "Temporal Cardiorenal Dynamics and Mortality Prediction After TAVR: The Prognostic Value of the 48–72 h BUN/EF Ratio" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020676

APA StyleÇelik, A., Kırış, T., Kayaaltı Esin, F., Babacan, S., Erdem, H., & Karaca, M. (2026). Temporal Cardiorenal Dynamics and Mortality Prediction After TAVR: The Prognostic Value of the 48–72 h BUN/EF Ratio. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020676