1. Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), developed before 2010 for curative en bloc resection of early pre-/malignant neoplasms, was introduced and validated by its Japanese pioneers, who later trained interventional endoscopists [

1,

2] and established national ESD centers [

3,

4]. ESD is now the state-of-the-art oncologic en bloc resection for early GI cancers and has been adopted in Western guidelines [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Supervised experimental training by Japanese experts enabled Western endoscopists to begin performing ESD independently [

12,

13]. However, ESD demands proficiency in two learning curves: precise optical diagnosis to determine appropriate indications and advanced electrosurgical endoscopic skills [

9]. Although Western endoscopists may train in Japan, due to legal restrictions, they cannot perform ESD on patients there. To address this, Naohisa Yahagi and Tsuneo Oyama—key founders of ESD—promoted an ESD tutoring program for beginners. The program was held in Salzburg (Austria) from 2011 to 2015 and remains unique in Western countries. Its goals were both to improve patient outcomes (primary objective) and simultaneously to teach accurate optical diagnosis and technical performance (secondary objectives). Here, we report the 10-year follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organization and Accreditation of ESD Tutoring

ESD Tutoring Program (

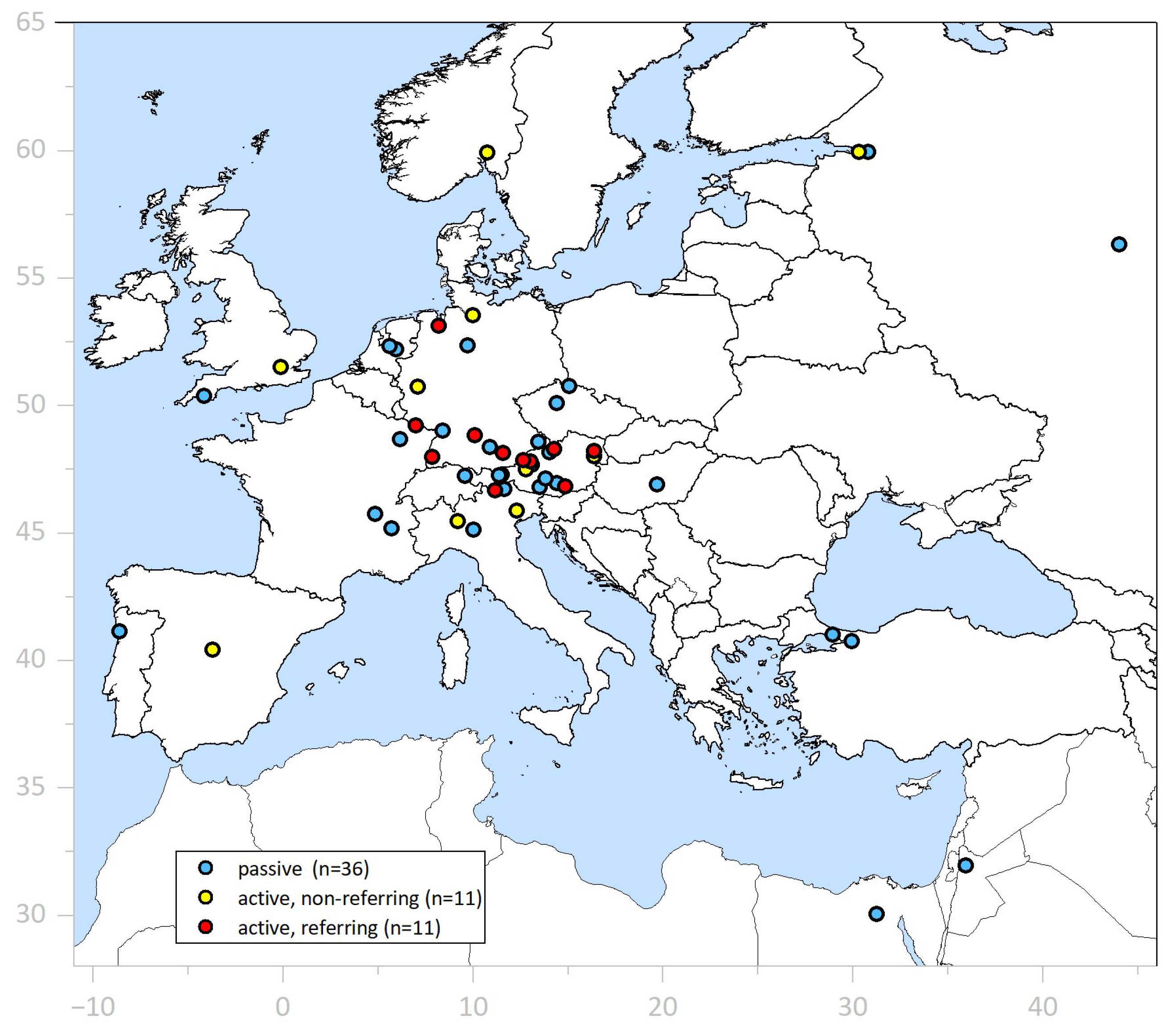

Supplementary Section S1). ESD-implementing endoscopists from 22 endoscopic centers—11 referring their own patients and 11 non-referring—as well as 36 non-assisting ESD beginners participated (

Figure 1).

All of them had been participating in an ESD Experimental Training & Update course [

13] and had initial experience in ESD. Four internationally renowned Japanese ESD experts (N.Y., T.O., T.T., and Toshio Uraoka) performed complete ESD procedures (n = 28) in 16 patients during 5 ESD live events [

13,

14], in 7 patients during TUTORING events, and in 5 unpublished tutored cases in 2009–2010 (not included in [

15,

16]). The remaining 90 ESDs were performed by ESD beginners, with or without completion by tutors, in 20 tutoring sessions (each lasting 1–4 days, totaling 49 days). A contribution by the trainee of ≥25% of the total ESD duration was recorded in the register. ESD Clinical Tutoring is part of inpatient therapy and was offered free of charge to the trainees. We recommended endoscopy within ≤1 year and further follow-up (1–5 yrs) or additional therapy according to concurrent recommendations [

17,

18,

19].

Referral of patients. Starting in November 2011, ESD-implementing centers of prospective trainees collected their cases for ESD tutoring at the University Hospital Salzburg. All 107 patients had been proposed for putative ESD with case vignettes, images, and the trainee’s optical diagnosis, and these data were forwarded to the Japanese experts. All 124 lesions fulfilled the criteria for endoscopic en bloc resection in Japan [

17,

19,

20]. Early cancer lesions graded superficial–invasive were additionally investigated with high-resolution endoscopic ultrasound (hrEUS, 20 MHz) for sm-invasion criteria, and stage cN0 was confirmed with conventional EUS (7.5 MHz) or/and CT scan before embarking on ESD ([

5] 1st ed. 2014). We excluded patients with evidence of lymph node or distant metastasis and—except for diagnostic ESD in the cardia and lower rectum—suspicion of deep submucosal invasion (≥sm2). As soon as the indication for ESD had been confirmed by the Japanese experts, informed consent was obtained, including the possibility of en bloc resection using the novel technique of ESD during tutoring and live events. In addition, the patient was specifically asked to consent in the tutoring, i.e., performance by the ESD trainee as well as the supervising Japanese expert, observation by a few ESD endoscopists for educational purposes, anonymized endoscopic video recording, follow-up of the patient’s outcome, and intent for publication (individual documentation of the above medical information provided to the patient was signed by both the patient and the organizer).

Documentation for study and legal purposes. In September 2009, the principal investigator instituted a prospective

register (

no. 1) of ESD-ITT in Excel and a document record file for the

untutored ESD cohort [

15,

16], and in November 2009, an analogous

register (

no. 2) for ESD

involving external experts. All ESD-ITT were documented in an Excel file for patient and lesion characteristics with visual classifications, endoscopic diagnosis, indications, operators, feasibility and safety parameters of ESD performance, such as duration (min) and dissection time by trainee, resection type (ESD, h-ESD, EID, pm-EMR), histopathological results, resection status (R1, Rx, R0, R curative) (Tables 2 in [

9,

10]), graded AE for inpatient procedures [

21] (analogous AGREE grading is for

outpatient procedures [

22]), and follow-up for survival status, morbidity, and recurrent and metachronous NPL. The record file is based on hospital records, consents, anonymized full-length video recordings of each endoscopic procedure, ESD strategy protocols, CME feedback, and patient contact data. The CME program was in effect from November 2011 until March 2015. Complete long-term follow-up (Aug.–Dec. 2024) was obtained from hospital records, referring ESD physicians, and patients.

Approval of ESD clinical tutoring. According to §36 of the Austrian Medical Practitioners Act [

23], the head of the department is entitled to apply for

teaching assistance from international experts when implementing novel operations, such as ESD for early cancers and suitable precursor lesions. However, he/she bears the

medical and legal responsibility for the endosurgical procedure on the patient. The requirements to approve Japanese experts as tutors and ESD-implementing gastroenterologists for assistance were met (with legal opinions issued in October 2011 by René Musey and Hans E Diemath, and confirmed in October 2024 by Johannes Zahrl, University of Vienna) (

Supplementary Section S1). The implementation of

established therapies and operations is not subject to ethics committee approval according to §30 of Salzburg County Hospitals Act (LGBI nr. 91/2010). Protocols no. 1, “

Implementation of ESD technique”, and no. 2, “Clinical ESD Tutoring & ESD Live Events” (LEE), had been approved by the internal review board of the University Hospital (IRB protocol no. 93/02.04.2009; 510/03.11.2011). Protocol no. 2 was further accredited for continued medical education (CME) by the Austrian Medical Chamber in September 2011 and by the ESGE in May 2012 (on the recommendation of Meinhard Classen (†)).

2.2. Performance of ESD Procedures

Optical diagnosis was performed by the ESD beginners in their hospital to predict low-grade vs. malignant histology, and superficial vs. deep (sm ≥ 2) submucosa-invasion—using classifications and indications [

9,

24] detailed since 2009 in syllabus scripts (classifications updated through personal communication with T Oyama in January 2012 and N Yahagi in March 2012) and in the derived endoscopy atlas ([

5] 1st ed. 2014) (for references see

Supplementary Section S1).

ESD techniques. We applied CO

2 insufflation and standard techniques for ESD with Dual-/J knife

®, Hook-/J knife

® (Olympus Europe, Hamburg, Germany), Flush knife BT

®, and Clutch cutter

® (

Fujifilm Europe GmbH, Ratingen, Germany) [

25,

26,

27,

28] (see

Supplementary Section S1). Specimen work-up and immunohistochemical/histopathologic evaluation in 2 mm serial sections were performed as previously described [

9,

15,

16,

29,

30].

Patients. For the ESD Tutoring and LEE programs, 101 patients underwent ESD-ITT on 118 lesions. Among these patients, aged 68 years [37–91] and with an ASA score of 2 [1–4], 38% presented with co-morbidity ≥ grade 3, and 30% were on oral anticoagulant or/and antiplatelet drugs. For 91 (77%) ESD-ITT patients, the POSPOM score predicted increased postoperative mortality (POM) for alternative surgical resection (score 25–41, risk of POM 2.5–23%;

Table 1A) [

31]. The very elderly (83 ± 7.6 yrs; n = 12) with a score 34–41 (POM risk 15–25%) would have been very poor candidates for surgery on cancers in the esophagus, cardia, stomach, right colon, or large LST-GM in the hepatic flexure or anorectum—but tolerated curative ESD well. Most of these high-risk patients (n = 7) received antibiotic prophylaxis after uncomplicated, large-size ESD (d ≥ 5 cm) in the colorectum or stomach [

32,

33].

Lesions. Table 1B shows the organ distribution of all NPLs, including size (mv ± SD) and Paris classification. In 9 patients, 17 additional lesions were resected en block by ESD-ITT. Fifty percent of ESD-ITT were performed on advanced NPL (HGIEN or cancer), both by tutors and trainees. Retrospectively, all indications, except symptomatic esophageal SETs and duodenal adenomas, correspond to current guidelines [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and lesions for ESD-ITT.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and lesions for ESD-ITT.

| (A) Patient Characteristics |

|---|

| | Details |

|---|

| Patients (n, %) | 101 (100%), 38% female/62% male |

| Age at ESD (yrs) | 68 [37–91] |

| ASA score (1–5) | 2 [1–4] |

| Co-morbidities ≥ grade 3 1 (38%) | CHF 26%, CVI 0.9%, CKD 5.6%, CPD 0.9%, LC 1.9%, IDDM 2.8% |

| Anticoagulation Therapy 2 (30%) | OAC 12%, AP 16%, OAC & AP 0.9%, LMW heparin 0.9% |

| POSPOM score (0–45) 3 | 27 [17–41] normal risk (POM < 2.5%) in 23% of 118 ESD-ITT |

| Increased POM risk, distribution (77% of 118 ESD) | Score | Risk

(% POM) | All ESD (118) | Tutor ESD (28) | Trainee ESD (90) |

| 25–29 | 2.5–5% | 53% | 68% | 43% |

| 30–41 | 6–23% | 24% | 10.5% | 29% |

| Intubation anesthesia | 1 hypopharynx-ESD, 17 esophagus-/cardia-ESD, 2 gastric ESD |

| (B) Lesions |

| | Total | Esophagus | Stomach | Duoden. | Rectum | Colon |

| SET | SC | Barrett |

| Patients (n) | 101 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 22 | 39 |

| ESD lesions 4 (n) | 118 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 24 | 49 |

| Malignant NPL 5 (n) | 59 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 17 |

| Size (cm) mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 1.9 | 6.4 ± 2.6 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 1.5 |

| 0-IIb/LST-NG 7 (n) | 39 | - | 5 | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | 30 |

| 0-IIa + c/LST-NGPD 5 | 23 | - | - | 1 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| 0-IIa + Is/LST-GM 6 (n) | 50 | 5 8 | 2 9 | 6 10 | 1 | 4 | 21 | 10 |

| 0-IIa/LST-GH 6 (n) | 7 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 4 | - | 1 |

| Biopsy, targeted (%) 11 | 67% | 40% | 100% | 100% | 79% | 56% | 75% | 43% |

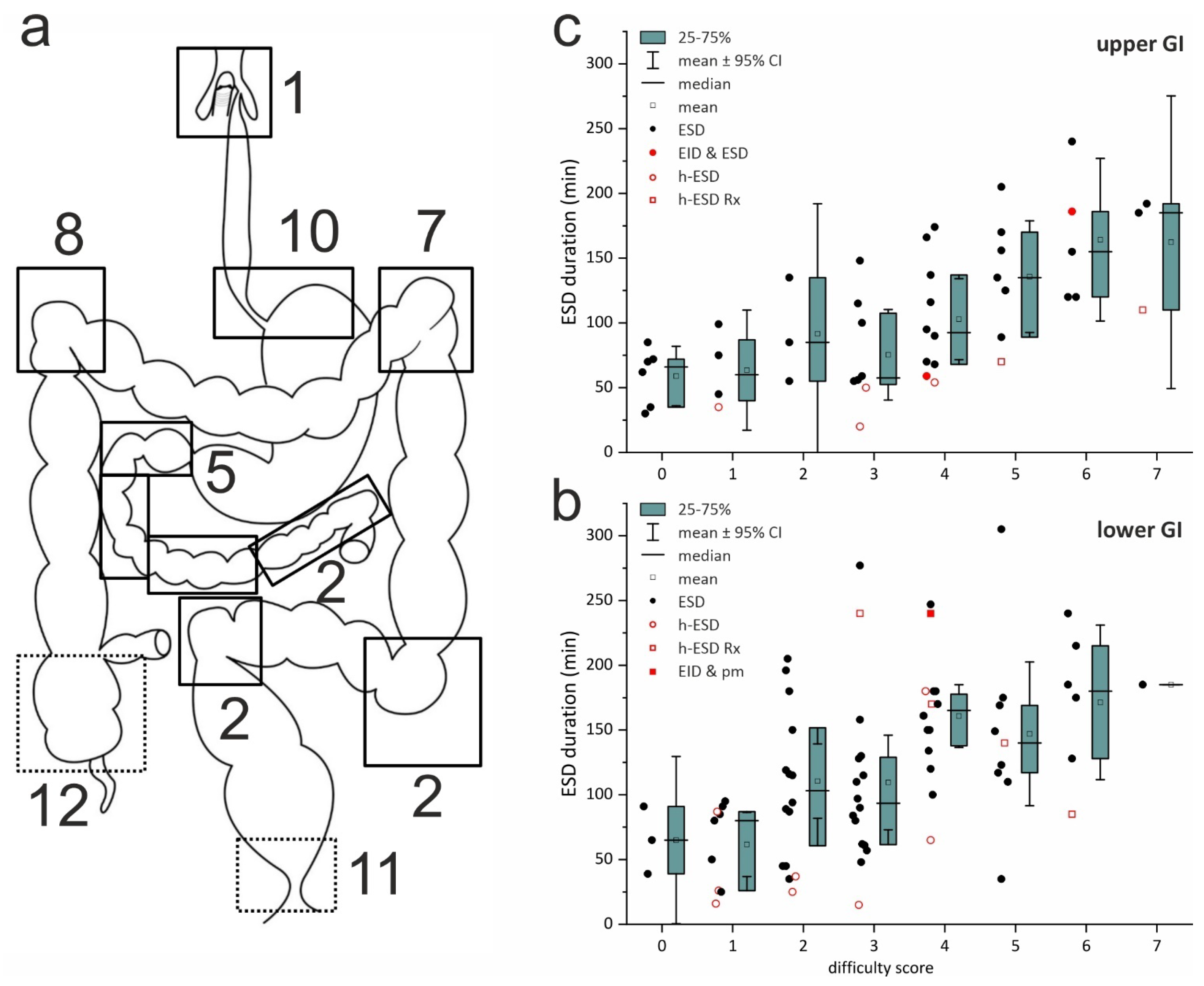

ESD difficulty score (

DS 0–8; difficult ≥ 2) predicts the difficulty of a planned ESD procedure (

Supplementary Section S1), is validated for correlation with the duration of ESD in the colorectum [

34], and was modified for ESD in the upper GIT for the current analysis (

Supplementary Figure S1). Retrospective DS analysis reveals that the majority of ESD lesions were difficult (DS 2–3; 35%) or very difficult (DS ≥ 4; 46%) (

secondary objective,

Figure 2a–c). Fifty percent of the lesions for ESD were located in the sites scored as most difficult (

Figure 2a), and there were 14 of 16 recurrent lesions after EMR, ESD, or surgery scoring +2 DS points. The score best correlates with the duration of ESD-ITT, both in the colorectum (R 0.515,

p < 0.0001)—confirming the validation—and in the upper GI tract (R 0.550,

p < 0.00001), supporting its exploratory use (

Figure 2b,c).

2.3. Data Analysis

Study design. The prospective cohort study has a modified ESD-ITT design, because we excluded 5 cases that the tutor assigned to alternative resection (pm-EMR, transanal microsurgery) and one published case [

35] (

Supplementary Table S1). The ESD-ITT dataset included 118 lesions in 101 patients. The

primary endpoint was patient outcome (resection status and recurrence rate).

Secondary outcomes were operability risk, trainee performance in optical classification and ESD indication (accuracy), and ESD performance on difficult lesions (feasibility and safety). Retrospective analysis of the anonymized data was granted by the Ethics Committee of Paracelsus Med. Univ. in March 2025 (2025_0005).

Statistical analysis. In the retrospective analysis, specimens’ area (as ellipsoid = ½ maximum length x ½ maximum width x π; in cm

2), risk of surgical resection (POSPOM score), and the difficulty score (DS) of ESD lesions (

Supplementary Figure S1) were calculated based on register no. 2 [

31,

34].

Continuous parameters were analyzed for mean ± standard deviation (SD), median [range], significance (

p < 0.05) for difference with one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s adjustment, and for Pearson correlation.

Categorical parameters were transformed into digit numbers—including endoscopic location (2 digits), classifications, difficulty score DS of ESD, and graded AE [

21]—and tested with Spearman regression for significant correlation with continuous parameters, and with one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test for significant differences (

p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Primary Objective: Outcome of All ESD Procedures

3.1.1. Patient Outcomes

En bloc and curative resection rates were 95% (including 11% hybrid-ESD) and 88%, with no recurrence after R0 resection (

Table 2A). En bloc rates were 98% for malignant and 92% (R0 88%) for benign NPLs, the latter due to elective hybrid-ESD (4%) involving final snaring in 2–3 fragments for four colonic and one duodenal adenoma (5 LGIEN, Rx; icons in

Figure 2b,c). Hybrid-ESDs achieved clear margins and shorter procedure times.

Supplementary Table S2A details the outcomes

by organ for benign and advanced lesions.

3.1.2. Non-Curative ESD and Recurrences

There were 5 recurrent lesions (4.2%): 3 cases after resection R1/Rx of adenomas (1 in the colon, 2 in the duodenum, all cured with a single hot snare polypectomy (HSP)), and an additional 2 cases after resection R1

h/R1

v of 2 malignant lesions (

Table 2A). The description of the final outcome (100% curative) after 7 non-curative ESDs (12%) is detailed in

Supplementary Table S3, cases no. 1–7.

3.1.3. Long-Term Outcome, Median Follow-Up of 9.8 [1.5–14.9] Years

As detailed in

Table 2B, clinical follow-up was 98% complete for 59 patients aged 75 ± 11 years; 54 of them had endoscopic recurrence-free survival (RFS) of 9.1 ± 2.1 years. The other five patients with symptomatic esophageal SET stayed asymptomatic after ESD (4 granular cell tumors, R0)/submucosal tunneling resection (1 leiomyoma, R0) with normal endoscopic findings after 0.8 ± 0.3 years, and one suffered acute cardiac death at age 82 after 7.4 years. The 42 deceased patients died on average at old age after 5.7 ± 3.2 yrs (RFS 4.1 ± 3.0 yrs), one from

metachronous SCC in the base of the tongue (OS 1.0, age 49 yrs), diagnosed in an advanced stage (cT4 N2b, M0) despite preceding UGI and ENT endoscopic follow-up. All other forty-one patients died from unrelated diseases, eight (19%) at age 75 ± 8 yrs from malignant diseases, and 33 (79%) from common causes at age 82 ± 8.5 years (73% males) matching normal life expectancy in Austria (males 78.5, females 83 yrs).

Metachronous colorectal lesions occurred in only 11 of 73 patients (

15%) during 10.3 ± 2.3 yrs. All were

adenomas < 2.5 cm with/without LGIEN and were resected with EMR without any AE of DC grade > I (

FAP, 2 cases; see

Supplementary Section S2).

3.2. Secondary Objectives: Adverse Events and Outcome of Expert vs. Tutored ESDs

Adverse events (

Table 2C). None of the 101 patients with 118 ESD-ITT had surgical repair or long-term morbidity (≥6 mo), and 30-day mortality was zero. AEs graded according to Dindo-Clavien (

DC) occurred in

9.3% [

21]. A single AE (

0.8%) was life-threatening (

DC IVa) in an 85-year-old female patient with delayed perforation 1 h after ESD in the Billroth-II gastric stump and subsequent NSTEMI due to unexpected coronary artery disease, grade IV. AEs were moderately severe (

DC IIIa) for 9 ESDs, i.e., transnasal endoscopy and antibiotics for

one aspiration under propofol, endoscopic hemostasis for

5 delayed bleedings, and repeated

endoscopic dilatations for stenosis of the cardia (1 case, 3 times) or anorectal channel (3 cases, 3, 4, and 9 times). Of six inconsequential mini-perforations of the colorectum, all remained asymptomatic, with one receiving antibiotic prophylaxis after delayed clipping (

1 DC II) and five after immediate clipping (

5 DC grade 0).

3.3. Outcome of Expert vs. Tutored ESDs

3.3.1. Diagnostic Performance

As shown in

Table 3A, trainees correctly staged 104 neoplasms on

optical classifications (

OC), as confirmed in the ESD specimens (

accuracy 88%),

over-staged 4% (4 LGIEN in LST-NG/PD as OC-superficial malignant and 1 rectum AC pT1a as VG-sm1), and

under-staged 8% (6 HGIEN as OC-benign in LST-GM, 1 SCC 0-Is pT1b, sm2 as OC-sm1, and 2 AC pT2 in cardia and lower rectum as OC-sm ≥ 2). Endoscopic grading yielded

89% curative indications for ESD of 105 NPL (104

benign + superficial-malignant with

classical criteria plus

1 NET cN0). Among 13 carcinomas cN0 graded sm-invasive, six (

5%) had

curative ESD indications for

expanded criteria, and seven (

6%) had

diagnostic indications—one for malignant cardia stenosis (

Figure 3a–c) and five for likely

deep invasion into submucosa ≥ sm2, i.e., 1 esophagus SCC 0-Is (79% risk of sm ≥ 2 invasion [

5]), 3 Barrett AC 0-Isp/0-Is (

Figure 4a–f), 1 lower rectum LST-GN (size 13 × 7 cm) with a cancer nodule—and 1 anastomotic recurrent SCC 0-IIb for

high risk of resection

R1h without safety margin at the anastomosis. For

muscle retracting signs, the expert converted ESD on both deep-invasive AC to intermuscular dissection (

EID) in the cardia (

Figure 4e) and in the lower rectum [

36] enabling curative surgical en bloc resection (for AC pT2; R1, see

Supplementary Table S3, nos. 5; 6).

3.3.2. ESD Performance

Trainees started as beginners at the initial learning or early competence level (2–42 prior ESDs) (see

Table 3B). When comparing the ESD difficulty score (DS) of lesions, referring trainees were involved in a similar proportion (29%) of very difficult lesions (DS ≥ 4) as sole tutors (32%), and non-referring trainees were involved in a proportion three times lower. Conversely, all trainees performed ESD on lesions with 33% smaller areas and twice as often on easy lesions (DS ≤ 1) compared with sole tutors. The differences between the groups are non-significant, and the performance levels of trainees reflect the quality of expert supervision and tutoring.

Nevertheless, trainees achieved self-completion of a median

75% [25–100%] of ESD-ITT, with high rates of en bloc (

96%) and R0 resection (

94%) that were similar in both subgroups—proving effective instructions and supervision during the procedures. Tutors performed ESD with professional average speed (9.3 ± 6.2 cm

2/h,

p = 0.12, Tukey (ANOVA) compared to trainees’ group), including the largest and most difficult lesions (22 ± 22.5 cm

2; DS 4 [0–7]). Tutors furthermore ensured that average duration (112 ± 59 min) of trainee ESDs did not exceed that of tutor ESDs (122 ± 69 min;

p = 0.47, Tukey (ANOVA)), and average performance speed (7.5 ± 5.2 cm

2/h) was maintained on a skilled level—by completing slower or very challenging procedures. Most CME procedures (95%) were completed within 3 h during the routine program. ESD trainees were involved in demanding ESDs and rated the tutoring as excellent CME, which was very helpful for ESD in their practice (

Supplementary Figure S2).

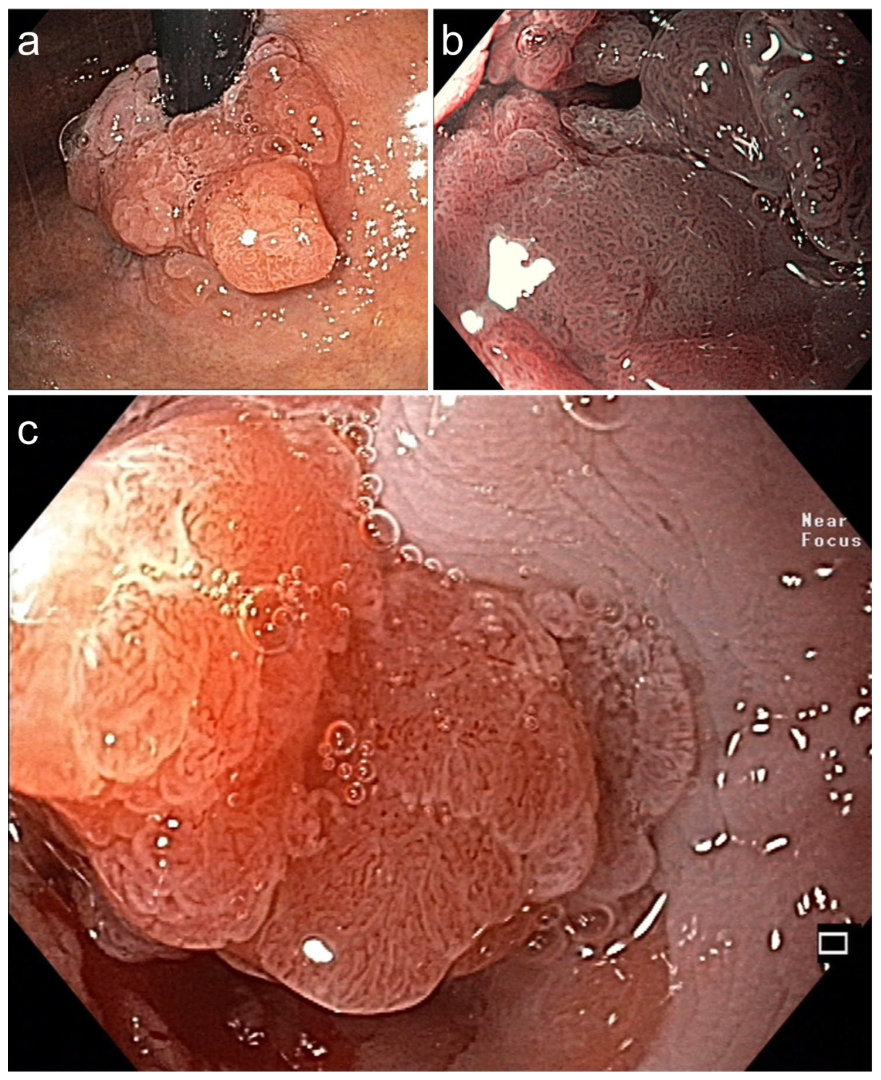

Figure 3.

Symptomatic circular Barrett adenocarcinoma 0-IIa+Is for diagnostic ESD en bloc (16.6 × 6 cm). (a) in the cardia (WLI, retroflex view) and (b) in stenosis (BLI, 40×, prograde: dense VP & SP). (c) Dense SP (regular epithelial white zone) & VP with V/S concordance (WLI 60×). Histopathology: AC, G1 pT1a, m2 L0 V0 pN0 Bd1, R curative. Died at age 87 from pneumonia, DFS 5.3 yrs.

Figure 3.

Symptomatic circular Barrett adenocarcinoma 0-IIa+Is for diagnostic ESD en bloc (16.6 × 6 cm). (a) in the cardia (WLI, retroflex view) and (b) in stenosis (BLI, 40×, prograde: dense VP & SP). (c) Dense SP (regular epithelial white zone) & VP with V/S concordance (WLI 60×). Histopathology: AC, G1 pT1a, m2 L0 V0 pN0 Bd1, R curative. Died at age 87 from pneumonia, DFS 5.3 yrs.

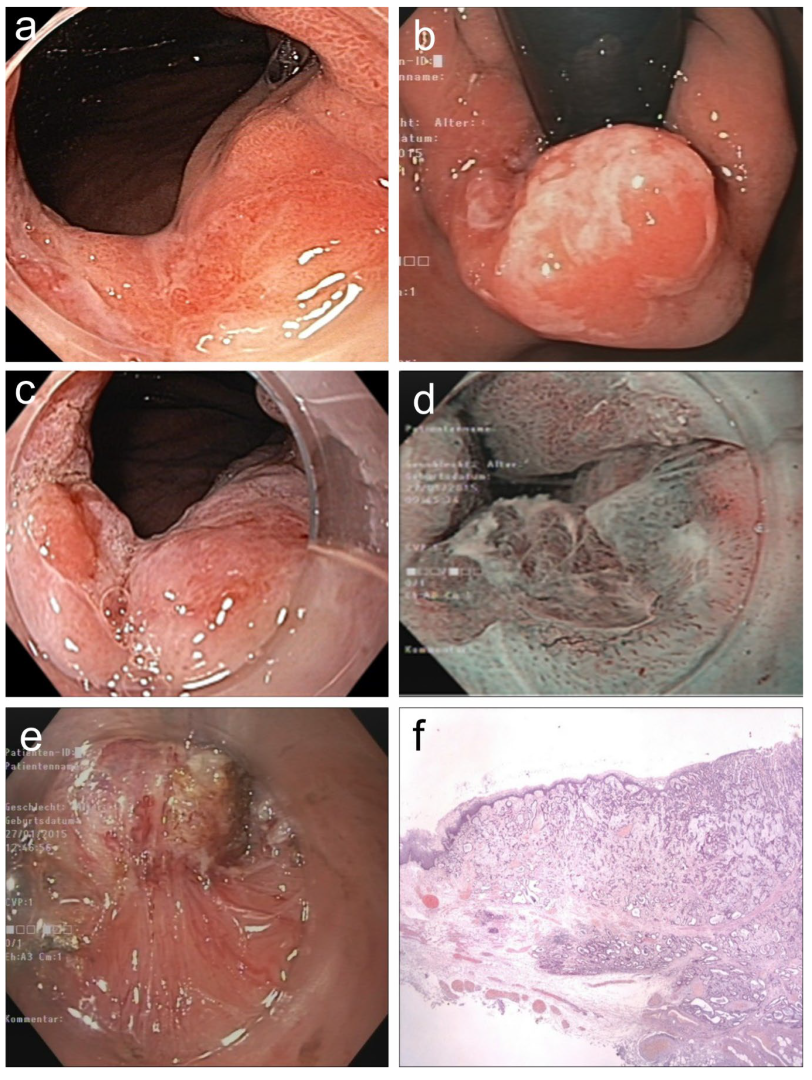

Figure 4.

(

a,

b).

Barrett adenocarcinoma 0-IIa+Is, semicircular (size 2.5 × 2 cm) in the cardia for

diagnostic ESD (EUS uT1m uN0), standard WLI in prograde (

a) and retroflex view (

b). (

c,

d) A small area (0.5 cm) on the base of 0-Is with irregular SP and V/S discordance ((

c) WLI 60×, (

d) NBI, 60×). (

e) pm-muscle retracting (

MR) sign [

36]. (

f) Section (HE stain 100×) of AC margin showing pm invasion and resection R1 (right lower end):

AC G2, pT2, R1. (

Supplementary Table S3, no. 5).

Figure 4.

(

a,

b).

Barrett adenocarcinoma 0-IIa+Is, semicircular (size 2.5 × 2 cm) in the cardia for

diagnostic ESD (EUS uT1m uN0), standard WLI in prograde (

a) and retroflex view (

b). (

c,

d) A small area (0.5 cm) on the base of 0-Is with irregular SP and V/S discordance ((

c) WLI 60×, (

d) NBI, 60×). (

e) pm-muscle retracting (

MR) sign [

36]. (

f) Section (HE stain 100×) of AC margin showing pm invasion and resection R1 (right lower end):

AC G2, pT2, R1. (

Supplementary Table S3, no. 5).

4. Discussion

Clinical tutoring by experts has rapidly implemented a network of professional centers for the novel, groundbreaking ESD technique in Japan [

3,

4]. This study aimed to transfer the ESD technique from Japan to the West with

ESD Clinical Tutoring based on teaching assistance by a Japanese expert during routine endoscopic treatment. The main findings of our analysis are that (i) patient outcomes meet professional standards for ESD as validated in Japan [

7,

8,

9,

11] and (ii) trainees achieved high rates of correct optical diagnosis as well as good clinical efficacy of ESD procedures.

The

data demonstrate an 88% curative resection rate for malignant lesions and zero recurrence after R0 resection of benign lesions in the setting of tutored ESDs. These data are far better than those reported for the untutored implementation of ESD. Thus, a meta-analysis of western ESD series (mainly during the stage of untutored implementation) reported mean en bloc resection rates of 81%, R0 rates of 71%, and overall curative rate of 67% [

3]. Analyses on simultaneous learning curves (up to 80–120 untutored ESDs) reported en bloc, R0, and curative resection rates of 75–85%, 65–74%, and 56–65%, respectively [

16,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. All our patients remained recurrence-free after endoscopic resection of 3 recurrent adenomas (at R1/Rx) and proper management of 7 non-curative ESDs. In addition, our trainees achieved a high rate of accurate optical diagnosis (88%) and ESD indication (96%) for benign and malignant lesions. ESD trainees under-staged two cases of deep cancer infiltration. In these cases, the expert applied endoscopic intermuscular dissection, which could accurately diagnose a pT2 G2 adenocarcinoma in the cardia and lower rectum, respectively, and subsequently enabled curative surgical en bloc resection. Tutored ESD trainees achieved regular procedure times (1–3 h) and maintained a skilled resection speed even for very difficult lesions. In addition, trainee self-completion rate was high (median 75; 25–100%), which is comparable to the self-completion rate of 74% that was achieved by skilled Japanese trainees during their first 40 tutored colorectal ESDs [

2]. On the one hand, there were trainee ESDs with 100% self-completion even on challenging complex lesions (DS 4–7) without recurrences. On the other hand, tutors managed that the duration of trainee ESD did not exceed that of tutors. The en bloc resection rate of 95% included 11% hybrid-ESD en bloc to shorten the duration of ESD, e.g., in the case of 2 or 3 colonic ESD in a single session. Elective final snaring with low current power showed precise margins of specimen and clean resection bed without any AE—confirming the findings of the original publication [

27]. In contrast,

conversion to hybrid-ESD during

untutored ESD-ITT mainly serves for self-completion in cases of long duration or perforation [

15,

16,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], which likely explains poor en bloc (68%) and R0 (61%) rates, as well as high perforation rate (5%) [

3].

Finally, the safety profile of the procedures performed during the tutoring program was favorable, which is remarkable since many elderly patients had a predicted high postoperative mortality rate. Thus, the outcome of the tutoring program meets the requirements for routine clinical therapy.

Limitations. While this study is unique, we do acknowledge several limitations: (i) The modified study design retrospectively analyzed novel predictive scores for the risk of alternative postoperative mortality and ESD difficulty of the lesions. However, based on a complete record file, this additional characterization provides an exemplary register for prospective studies on endoscopic resection of complex and putative malignant neoplasms. POSPOM score anticipates risk for surgical en bloc resection [

31], while ESD en bloc is becoming an alternative for surgery in oncological regimens [

43]. The predictive ESD difficulty score—pending validation for the upper GI tract—may improve strategy for and outcome of difficult ESD, and provide cut-off values for operator skills as well as referral to expert centers [

44]. (ii) The indications were prevalence-based and thus included a high proportion of colorectal and esophageal lesions. However, since early gastric cancer—the typical beginner’s lesion in Japan—is less prevalent in Europe, this approach reflects the clinical reality. (iii) The lesions referred were biased towards difficult and challenging ESD—yet the steep gradient of ESD difficulty highlights the quality of our tutorials and was reflected by positive feedback from the trainees—many of whom subsequently published their own ESD data [

13,

15,

16,

39,

41,

45,

46,

47]. (iv) Finally, the study was conducted at a single center with Japanese experts and trainees with initial ESD experience and therefore might not be fully generalizable to ESD proctoring in a Western setting, even though ESD expert centers have been recently established in Europe.

Indeed, it has to be emphasized that the success of the ESD clinical tutoring concept only applies for

strict preconditions: the

Japanese top expert tutors with profound ESD teaching and tutoring experience, interventional endoscopists nearly on ESD competence level from major centers, referring patients with NPL classified for indication and difficulty of ESD to a single center, and medical and legal responsibility of the head of department for the ESD involving referring doctor and tutor. Nevertheless, such tutoring experts with refined ESD techniques [

43,

44,

48], shall be available for another decade to advance professional ESD performance. This

ESD Clinical Tutoring concept—with the co-operation of 6–10 centers—could serve to establish networks of Early Cancer Centers (e.g., 1 per 5–7 Mio. population) in Europe [

9].

Implications of This Study

This Clinical Tutoring concept obviates the exclusion of very frequent colonic indications—and other challenging lesions—from the stage of ESD implementation. Furthermore, some western endoscopists successfully implemented colorectal ESD in an untutored fashion with technical step-up and good safety [

15,

16,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42], and one later introduced ESD on early cancers of the upper GI tract with near professional performance level [

46].

In addition, Tutoring ESD sessions included the most difficult lesions for ESD and may have reduced the need for alternative oncological surgery, as well as enhanced the learning curve of ESD beginners, thus saving resources and costs.

Between 2011 and 2015, this was the only one-to-one hands-on clinical training course in Europe for both ESD indication and electrosurgical ESD skills, led by top experts from Japan. This training course proved feasible for routine endoscopic treatment. At that time, this represented the best minimally invasive treatment for early GI cancer patients available in Europe. The ESD Tutoring continued as an ESD Clinical Tutoring Course in Munich 2019 (Organizers: Ch Schlag, R Schmid & F Berr) (further on interrupted by COVID-19 pandemia), and 2016–2025 as CME events in Freiburg (Organizer: H-P Allgaier, I Steinbrück), Bonn (Organizer: F-L Dumoulin), Germany, and as annual eNNdo Days in Nizhniy Novgorod (Organizer: A T Mitrakov), Russian Federation.

5. Conclusions

ESD Clinical Tutoring Courses under Japanese expert supervision ensure excellent patient outcomes and consistent procedural standards during routine treatment. This model may foster professional ESD performance across European referral centers and—as a cooperative program—promote networks of Early GI cancer Centers in Europe.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm15020675/s1: Section S1. Supplementary Approval [

49] Supplementary Methods: Optical classifications [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59], endoscopic en-bloc resection techniques [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Section S2. Supplementary Results including Supplementary Table S1 Excluded cases scheduled for ESD Tutoring and LEE Program, Supplementary Table S2A Detailed Outcome of ESD-intention to treat (ESD-ITT), Supplementary Table S3 Outcome of non-curative ESD-ITT, Supplementary Figure S1 Predictive ESD Difficulty Score for lesion items and anatomical location, Supplementary Figure S2 Feedback of ESD implementing endoscopists for the ESD Tutoring program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N., N.Y., T.O., T.T., T.K., A.W., F.L.D., H.-P.A., H.S., I.S., J.H. (Juergen Hochberger), T.P., F.B.; Data curation, D.N., T.K., A.W., F.B.; Formal analysis, D.N., T.K., A.W., F.B.; Funding acquisition, D.N., N.Y., T.P., F.B.; Investigation, D.N., N.Y., T.O., T.T., T.K., A.W., F.L.D., A.Z., H.-P.A., M.A., G.K., H.S., A.H.d.T., I.S., B.T., A.T., J.H. (Josef Holzinger), A.E., J.S.-A., J.H. (Juergen Hochberger), S.V.K., M.P., T.P., F.B. and ESD Tutoring Training Group; Methodology, D.N., N.Y., T.O., T.T., T.K., F.L.D., H.S., I.S., S.V.K., M.P., T.P., F.B.; Project administration, A.W., T.P., F.B.; Resources, A.W., A.Z., H.-P.A., M.A., G.K., H.S., A.H.d.T., I.S., J.H. (Josef Holzinger), F.B. and ESD Tutoring Training Group; Software, T.K.; Supervision, N.Y., T.O., T.T., F.L.D., J.H. (Josef Holzinger), J.S.-A., J.H. (Juergen Hochberger), S.V.K., T.P., F.B.; Visualization, D.N., T.K., F.B.; Writing—original draft, D.N., T.K., A.W., F.L.D., F.B., Writing—review & editing, D.N., N.Y., T.O., T.T., T.K., A.W., F.L.D., A.Z., H.-P.A., M.A., G.K., H.S., A.H.d.T., I.S., B.T., A.T., J.H. (Josef Holzinger), A.E., J.S.-A., J.H. (Juergen Hochberger), S.V.K., M.P., T.P., F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Organizational costs of the

ESD Tutoring program were covered by

unrestricted educational grants from Leonie-Wild Foundation/Eppelheim, Germany. Costs for 5 ESD-UPDATE LEE (5 days) were covered by the

Experimental ESD Training Program [13].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Protocols no. 1, “Implementation of ESD technique”, and no. 2, “Clinical ESD Tutoring & ESD Live Events” (LEE), were approved by the internal review board of the University Hospital Salzburg (IRB protocols no. 93/02.04.2009; 510/03.11.2011), and no. 2 was accredited for continued medical education (CME) by the Austrian Medical Chamber in Sept. 2011, and the ESGE in April 2012.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study, including written consent to publish this paper (compare Methods

Section 2.1).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

For contribution to this study, the organizers thank the ESD Tutoring Training Group: Manfred Lutz (Caritasklinikum, Saarbrücken, Germany), Klaus Heiler (Klinikum SOB, Traunstein, Germany), Dieter Plamenig (LKH-Spital, Wolfsberg, Austria), Christian Oesterreicher (Hanusch-Spital, Vienna, Austria), Christoph Schlag (Univ. Hospital, Zuerich, Switzerland), Alexandr Mitrakov (Univ. Cancer Hospital, Nizhniy Novgorod, Russian Federation), Pietro Gambitta (Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milan, Italy), Alexandr Filin (Leningrad Regional Hospital, St Petersburg, Russian Federation), Anton Glas (Klinikum Passau, Passau, Germany), Jean Baptiste Chevaux (Univ. Hospital, Nancy, France), Stepan Suchánek (Military Hospital, Charles University, Prague, Czeck Republic), Paul Hengster (Univ. Hospital, Innsbruck, Austria), Achim Lutterer (City Hospital, Karlsruhe, Germany), Chris Hayward (Univ. Hospital, Plymouth U.K.), Kalid Kheshk (NHS Hospitals, Plymouth, U.K.), John N Groen (St. Jansdal Hospital, Harderwijk, NL), Tarek Qtob (Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan), Göktuk Sirin (Kocaeli Univ. School of Medicine, İzmit, Turkey), Kayihan Gunay (Istanbul Univ. Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey), Petr Richter (Gastro Ctr. Liberec, Czeck Rep.), György Guymesigy (Univ. Hospital, Kecskemét, Hungary), Rees Cameron (City Hospital, Wellington, New Zealand). The organizers thank, for the promotion of the CME program, Meinhard Classen (†)/Kitzbühel, and Heinrich Magometschnigg, Peter Gerner, Eva Rhode, and Herbert Resch/Paracelsus Med. Univ. Hospital Salzburg; for providing CME, Toshio Uraoka/Maebashi, Akiko Takahashi/Saku City, Japan; and for support, the endoscopy assistant team led by F. Fuschlberger and R. Wallner. We thank the Leonie-Wild Foundation/Eppelheim, Germany for unrestricted CME grants, Olympus, Fujifilm, DiLena, ERBE Medizintechnik for technical support, and for legistic expertise J. Zahrl/Section Medical Law, Univ. Vienna, H.-E. Diemath/medical law expert and R. Musey/lawyer, Salzburg; and for patient referrals for ESD-ITT A. Kriegisch (Tamsweg, AT), F. Krempler (Hallein, AT), W. Fortunat (Wolfsberg, AT), F. Waidmann (Friesach, AT), K. Pamsl (Spittal, AT), and W. Bellmann (Freilassing, DE).

Conflicts of Interest

The ESD Tutoring Program was tutoring and teaching time without remuneration devoted to the CME of endoscopic visual diagnosis and electrosurgical skills during regular state-of-the-art endoscopic therapy (ESD) of diseased patients. The tutoring faculty used their customary ESD devices for treatment without promoting them. The following tutoring faculty disclosed financial relationships: N. Yahagi: Consulting fees from Olympus, Fujifilm, and Boston Scientific; and patents planned, issued, or pending for Olympus, Pentax, and Boston Scientific. T. Toyonaga: Royalties or licenses from Olympus and Fujifilm. S. V. Kantsevoy: Consulting fees for Olympus, Medtronic, Lumendi, and Noah Surgical; participation on Lumendi Advisory Board; stock or stock options from Lumendi, Vizballoon, EndoCages, and Slater Endoscopy; other financial or nonfinancial interests for Endocages (Cofounder). M Pioche: Trainer in ESD for Olympus, Pentax, consultant of Olympus, co-founder of ATRaCt Company, co-holder of ipefix patent. All other authors contributed as LEE faculty or ESD implementing trainees without conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | adenocarcinoma |

| AE | adverse event |

| APC | argon plasma coagulation |

| BLI/NBI/WLI | Blue-/Narrow-Band-/White-Light-Imaging |

| CME | Continued Medical Education |

| ESD | Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection |

| h-ESD | hybrid-ESD |

| -ITT | -intention-to-treat |

| ESGE | European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy |

| FAP | familial adenomatous polyposis |

| G1/G2/G3 | grading G1/G2/G3 |

| GI(T) | gastrointestinal (tract) |

| JNET | Japan NBI Expert Team |

| HGIEN | high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| HSP | hot snare polypectomy |

| LGIEN | low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| NET | neuroendocrine tumor |

| NEC | neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| NPL | neoplasia |

| pm | proper muscle layer |

| pmEMR | peace meal Endoscopic Mucosal Resection |

| mNBI | magnifying NBI |

| sm | submucosa(l) layer |

| OC | optical classification of NPL |

| OS | overall survival time |

| DFS | disease-free survival time |

| RFS | recurrence-free survival time (for benign neoplasias) |

| SCC | squamous cell carcinoma |

| R1h/R1v | resection with positive horizontal/vertical margin |

| SET | subepithelial tumor |

References

- Hotta, K.; Oyama, T.; Shinohara, T.; Miyata, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Kitamura, Y.; Tomori, A. Learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection of large colorectal tumors. Dig. Endosc. 2010, 22, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, T.; Saito, Y.; Fukunaga, S.; Nakajima, T.; Matsuda, T. Learning curve associated with colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection for endoscopists experienced in gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2011, 54, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuccio, L.; Hassan, C.; Ponchon, T.; Mandolesi, D.; Farioli, A.; Cucchetti, A.; Frazzoni, L.; Bhandari, P.; Bellisario, C.; Bazzoli, F.; et al. Clinical outcomes after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 86, 74–86.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Tamegai, Y.; Tsuda, S.; Saito, Y.; Yahagi, N.; Yamano, H.O. Multicenter questionnaire survey on the current situation of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection in Japan. Dig. Endosc. 2010, 22, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berr, F.; Oyama, T.; Ponchon, T.; Yahagi, N. (Eds.) Atlas of Early Neoplasias of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Endoscopic Diagnosis and Therapeutic Decisions, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, N.; Elhanafi, S.E.; Al-Haddad, M.A.; Thosani, N.C.; Draganov, P.V.; Othman, M.O.; Ceppa, E.P.; Kaul, V.; Feely, M.M.; Sahin, I.; et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on endoscopic submucosal dissection for the management of early esophageal and gastric cancers: Summary and recommendations. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, R.; Arima, M.; Iizuka, T.; Oyama, T.; Katada, C.; Kato, M.; Goda, K.; Goto, O.; Tanaka, K.; Yano, T.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection guidelines for esophageal cancer. Dig. Endosc. 2020, 32, 452–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Yao, K.; Fujishiro, M.; Oda, I.; Uedo, N.; Nimura, S.; Yahagi, N.; Iishi, H.; Oka, M.; Ajioka, Y.; et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig. Endosc. 2021, 33, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Yahagi, N.; Ponchon, T.; Kiesslich, T.; Berr, F. How to establish endoscopic submucosal dissection in Western countries. World. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 11209–11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Libanio, D.; Bastiaansen, B.A.J.; Bhandari, P.; Bisschops, R.; Bourke, M.J.; Esposito, G.; Lemmers, A.; Maselli, R.; Messmann, H.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2022. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Kashida, H.; Saito, Y.; Yahagi, N.; Yamano, H.; Saito, S.; Hisabe, T.; Yao, T.; Watanabe, M.; Yoshida, M.; et al. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig. Endosc. 2020, 32, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berr, F.; Ponchon, T.; Neureiter, D.; Kiesslich, T.; Haringsma, J.; Kaehler, G.F.; Schmoll, F.; Messmann, H.; Yahagi, N.; Oyama, T. Experimental endoscopic submucosal dissection training in a porcine model: Learning experience of skilled Western endoscopists. Dig. Endosc. 2011, 23, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, T.; Yahagi, N.; Ponchon, T.; Kiesslich, T.; Wagner, A.; Toyonaga, T.; Uraoka, T.; Takahashi, A.; Ziachehabi, A.; Neureiter, D.; et al. Implementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection in Europe: Survey after 10 ESD Expert Training Workshops, 2009 to 2018. iGIE 2023, 2, 472–480.e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Hassan, C.; Meining, A.; Aabakken, L.; Fockens, P.; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Live endoscopy events (LEEs): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Position Statement—Update 2014. Endoscopy 2015, 47, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berr, F.; Wagner, A.; Kiesslich, T.; Friesenbichler, P.; Neureiter, D. Untutored learning curve to establish endoscopic submucosal dissection on competence level. Digestion 2014, 89, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Neureiter, D.; Kiesslich, T.; Wolkersdorfer, G.W.; Pleininger, T.; Mayr, C.; Dienhart, C.; Yahagi, N.; Oyama, T.; Berr, F. Single-center implementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in the colorectum: Low recurrence rate after intention-to-treat ESD. Dig. Endosc. 2018, 30, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, M. Perspective on the practical indications of endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastrointestinal neoplasms. World. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 4289–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, D.A.; Rex, D.K.; Winawer, S.J.; Giardiello, F.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Levin, T.R. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: A consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y. JGCA (The Japan Gastric Cancer Association). Gastric cancer treatment guidelines. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 34, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S.; Oka, S.; Kaneko, I.; Hirata, M.; Mouri, R.; Kanao, H.; Yoshida, S.; Chayama, K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: Possibility of standardization. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 66, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, K.J.; Zwager, L.W.; van der Vlugt, M.; Dekker, E.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; Ravindran, S.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; Fockens, P. Novel classification for adverse events in GI endoscopy: The AGREE classification. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 95, 1078–1085.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austrian Medical Practioners Act 1998 (Ärztegesetz 1998), paragraph 36, number 3. Physicians with a Foreign Place of Practice or Employment—Last Update 01.01.2023. Federal Law Gazette (BGBl) I No. 169/1998; European Legislation Identifier (ELI). Available online: https://ris.bka.gv.at/eli/bgbl/i/1998/169/P36/NOR40250631 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Oyama, T.; Inoue, H.; Arima, M.; Momma, K.; Omori, T.; Ishihara, R.; Hirasawa, D.; Takeuchi, M.; Tomori, A.; Goda, K. Prediction of the invasion depth of superficial squamous cell carcinoma based on microvessel morphology: Magnifying endoscopic classification of the Japan Esophageal Society. Esophagus 2017, 14, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, T.; Tomori, A.; Hotta, K.; Morita, S.; Kominato, K.; Tanaka, M.; Miyata, Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 3, S67–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyonaga, T.; Man, I.M.; Fujita, T.; Nishino, E.; Ono, W.; Morita, Y.; Sanuki, T.; Masuda, A.; Yoshida, M.; Kutsumi, H.; et al. The performance of a novel ball-tipped Flush knife for endoscopic submucosal dissection: A case-control study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyonaga, T.; Man, I.M.; Morita, Y.; Sanuki, T.; Yoshida, M.; Kutsumi, H.; Inokuchi, H.; Azuma, T. The new resources of treatment for early stage colorectal tumors: EMR with small incision and simplified endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig. Endosc. 2009, 21, S31–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, N.; Fujishiro, M.; Imagawa, A.; Kakushima, N.; Iguchi, M.; Omata, M. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for the Reliable en bloc Resection of Colorectal Mucosal Tumors. Dig. Endosc. 2004, 16, s89–s92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwers, G.Y.; Carneiro, F.; Graham, D.Y.; Curado, M.P.; Franceschi, S.; Montgomery, E.; Tatematsu, M.; Hattori, T. Gastric carcinoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System; Bosman, F.T., Carneiro, F., Hruban, R.H., Theise, N.D., Eds.; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Schlemper, R.J.; Riddell, R.H.; Kato, Y.; Borchard, F.; Cooper, H.S.; Dawsey, S.M.; Dixon, M.F.; Fenoglio-Preiser, C.M.; Flejou, J.F.; Geboes, K.; et al. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 2000, 47, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Manach, Y.; Collins, G.; Rodseth, R.; Le Bihan-Benjamin, C.; Biccard, B.; Riou, B.; Devereaux, P.J.; Landais, P. Preoperative Score to Predict Postoperative Mortality (POSPOM): Derivation and Validation. Anesthesiology 2016, 124, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, A.S.o.P.; Khashab, M.A.; Chithadi, K.V.; Acosta, R.D.; Bruining, D.H.; Chandrasekhara, V.; Eloubeidi, M.A.; Fanelli, R.D.; Faulx, A.L.; Fonkalsrud, L.; et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, L.; Carbone, L.; Poto, G.E.; Calomino, N.; Neri, A.; Piagnerelli, R.; Fontani, A.; Verre, L.; Savelli, V.; Roviello, F.; et al. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Reduces the Rate of Surgical Site Infection in Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shi, Q.; Xu, E.P.; Yao, L.Q.; Cai, S.L.; Qi, Z.P.; Sun, D.; He, D.L.; Yalikong, A.; Lv, Z.T.; et al. Prediction of technically difficult endoscopic submucosal dissection for large superficial colorectal tumors: A novel clinical score model. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 94, 133–144.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantsevoy, S.V.; Wagner, A.; Mitrakov, A.A.; Thuluvath, A.J.; Berr, F. Rectal reconstruction after endoscopic submucosal dissection for removal of a giant rectal lesion. VideoGIE 2019, 4, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyonaga, T.; Tanaka, S.; Man, I.M.; East, J.; Ono, W.; Nishino, E.; Ishida, T.; Hoshi, N.; Morita, Y.; Azuma, T. Clinical significance of the muscle-retracting sign during colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc. Int. Open 2015, 3, E246–E251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barret, M.; Lepilliez, V.; Coumaros, D.; Chaussade, S.; Leblanc, S.; Ponchon, T.; Fumex, F.; Chabrun, E.; Bauret, P.; Cellier, C.; et al. The expansion of endoscopic submucosal dissection in France: A prospective nationwide survey. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronnow, C.F.; Uedo, N.; Toth, E.; Thorlacius, H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of 301 large colorectal neoplasias: Outcome and learning curve from a specialized center in Europe. Endosc. Int. Open 2018, 6, E1340–E1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, M.; Hildenbrand, R.; Oyama, T.; Sido, B.; Yahagi, N.; Dumoulin, F.L. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for flat or sessile colorectal neoplasia > 20 mm: A European single-center series of 182 cases. Endosc. Int. Open 2016, 4, E895–E900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychalski, M.; Dziki, A. Safe and efficient colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection in European settings: Is successful implementation of the procedure possible? Dig. Endosc. 2015, 27, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbruck, I.; Faiss, S.; Dumoulin, F.L.; Oyama, T.; Pohl, J.; von Hahn, T.; Schmidt, A.; Allgaier, H.P. Learning curve of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) with prevalence-based indication in unsupervised Western settings: A retrospective multicenter analysis. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 2574–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ly, E.K.; Nithyanand, S.; Modayil, R.J.; Khodorskiy, D.O.; Neppala, S.; Bhumi, S.; DeMaria, M.; Widmer, J.L.; Friedel, D.M.; et al. Learning Curve for Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection With an Untutored, Prevalence-Based Approach in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 580–588.e581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minashi, K.; Nihei, K.; Mizusawa, J.; Takizawa, K.; Yano, T.; Ezoe, Y.; Tsuchida, T.; Ono, H.; Iizuka, T.; Hanaoka, N.; et al. Efficacy of Endoscopic Resection and Selective Chemoradiotherapy for Stage I Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 382–390.e383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, N.; Maehata, T. What is important for a smooth implementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection? Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 94, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambitta, P.; Iannuzzi, F.; Ballerini, A.; D’Alessandro, A.; Vertemati, M.; Bareggi, E.; Pallotta, S.; Fontana, P.; Aseni, P. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for type 0-II superficial gastric lesions larger than 20 mm. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2018, 31, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocker, L.; Hildenbrand, R.; Oyama, T.; Sido, B.; Yahagi, N.; Dumoulin, F.L. Implementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early upper gastrointestinal tract cancer after primary experience in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc. Int. Open 2019, 7, E446–E451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimingstorfer, P.; Biebl, M.; Gregus, M.; Kurz, F.; Schoefl, R.; Shamiyeh, A.; Spaun, G.O.; Ziachehabi, A.; Fuegger, R. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract and the Need for Rescue Surgery-A Multicenter Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takehana, T.; Oyama, T.; Kato, M.; Yoshii, S.; Hoteya, S.; Nonaka, S.; Yoshimizu, S.; Yoshida, M.; Ohata, K.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Versus Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Cooperative Surgery for Superficial Duodenal Epithelial Tumors: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2025, 9, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the Application of Patients’ Rights in Cross-Border Healthcare. Official Journal of the European Union, L 88/45, Chapter I, Article 1, Chapter III, Articles 7-8. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:088:0045:0065:en:PDF (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: Esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003, 58, S3–S43. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, R.; Inoue, T.; Uedo, N.; Yamamoto, S.; Kawada, N.; Tsujii, Y.; Kanzaki, H.; Hanafusa, M.; Hanaoka, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; et al. Significance of each narrow-band imaging finding in diagnosing squamous mucosal high-grade neoplasia of the esophagus. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, M.; Yao, K.; Kaise, M.; Kato, M.; Uedo, N.; Yagi, K.; Tajiri, H. Magnifying endoscopy simple diagnostic algorithm for early gastric cancer (MESDA-G). Dig. Endosc. 2016, 28, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T. (Ed.) Endoscopic Diagnosis of Gastric Adenocarcinoma for ESD; Nankodo: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos, G.K.; Yao, K.; Kaye, P.; Hawkey, C.J.; Ragunath, K. Novel endoscopic observation in Barrett’s oesophagus using high resolution magnification endoscopy and narrow band imaging. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 26, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T. (Ed.) Superficial Barrett’s Esophagus Carcinoma; Nankodo: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, S.; Lambert, R.; Allen, J.I.; Fujii, H.; Fujii, T.; Kashida, H.; Matsuda, T.; Mori, M.; Saito, H.; Shimoda, T.; et al. Nonpolypoid neoplastic lesions of the colorectal mucosa. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008, 68, S3–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Horimatsu, T.; Fu, K.I.; Katagiri, A.; Muto, M.; Ishikawa, H. Magnifying Observation Of Microvascular Architecture Of Colorectal Lesions Using A Narrow-Band Imaging System. Dig. Endosc. 2006, 18, S44–S51. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S.; Sano, Y. Aim to unify the narrow band imaging (NBI) magnifying classification for colorectal tumors: Current status in Japan from a summary of the consensus symposium in the 79th Annual Meeting of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. Dig. Endosc. 2011, 23, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farraye, F.A.; Odze, R.D.; Eaden, J.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; McCabe, R.P.; Dassopoulos, T.; Lewis, J.D.; Ullman, T.A.; James, T., 3rd; McLeod, R.; et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T. Counter traction makes endoscopic submucosal dissection easier. Clin. Endosc. 2012, 45, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Superficial Esophageal Cancer. In Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: Principles and Practice; Fukami, N., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Toyonaga, T.; Nishino, E.; Man, I.M.; East, J.E.; Azuma, T. Principles of quality controlled endoscopic submucosal dissection with appropriate dissection level and high quality resected specimen. Clin. Endosc. 2012, 45, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, N. ESD for Colorectal Lesions. In Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: Principles and Practice; Fukami, N., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, H.; Ikeda, H.; Hosoya, T.; Onimaru, M.; Yoshida, A.; Eleftheriadis, N.; Maselli, R.; Kudo, S. Submucosal endoscopic tumor resection for subepithelial tumors in the esophagus and cardia. Endoscopy 2012, 44, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyonaga, T.; Ohara, Y.; Baba, S.; Takihara, H.; Nakamoto, M.; Orita, H.; Okuda, J. Peranal endoscopic myectomy (PAEM) for rectal lesions with severe fibrosis and exhibiting the muscle-retracting sign. Endoscopy 2018, 50, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |