Current Challenges of Managing Fibrosis Post Glaucoma Surgery and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

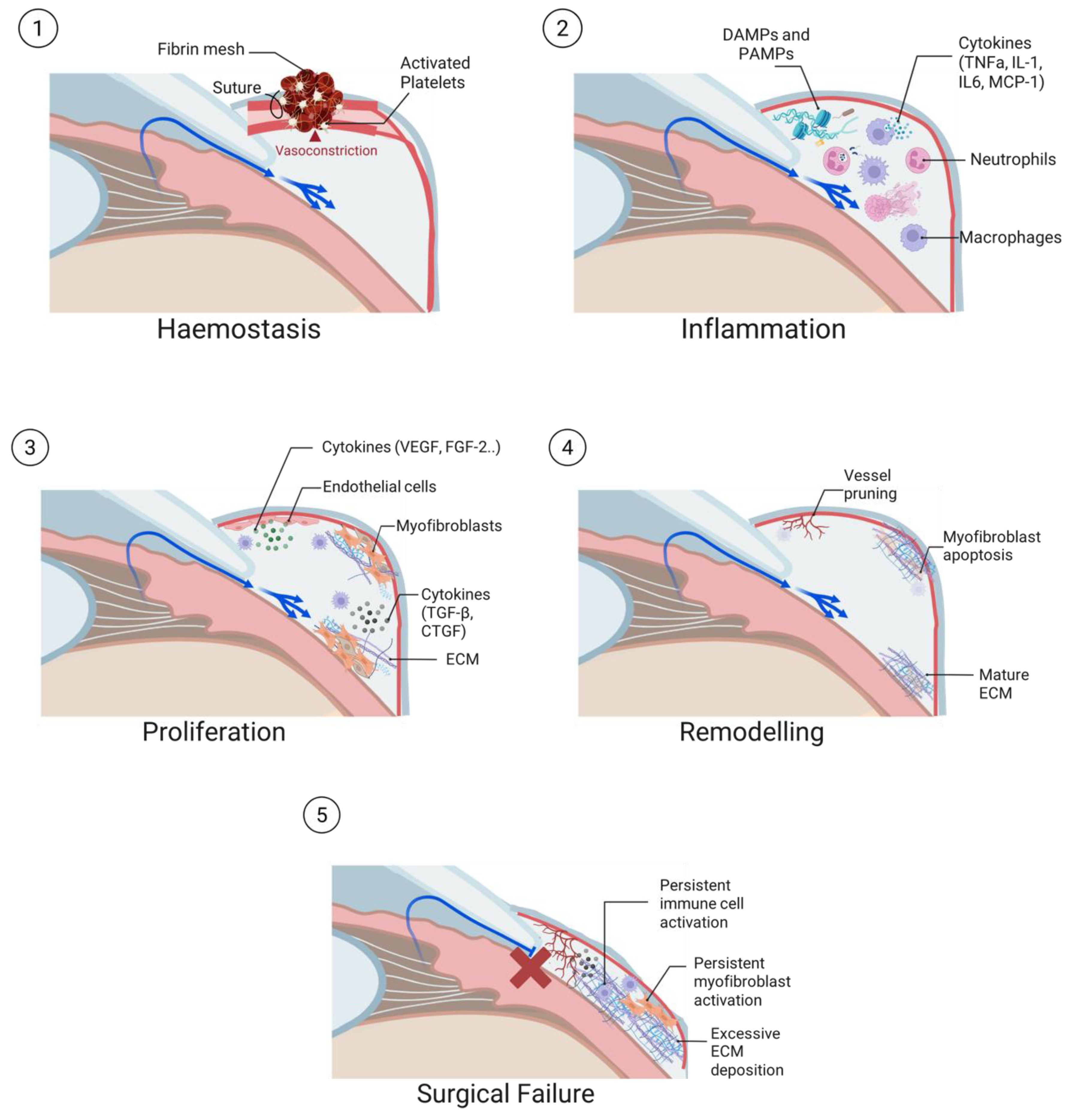

2. Wound Healing and the Conjunctival Fibrotic Response

2.1. Haemostasis

2.2. Inflammation

2.3. Proliferation

2.4. Tissue Remodelling

2.5. Conjunctival Fibrotic Response in Trabeculectomy

3. Strategies to Prevent Fibrosis Following Glaucoma Filtration Surgery

4. Future Directions

4.1. Investigative Drugs

4.2. Preclinical Drugs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| MIBS | Minimally Invasive Bleb Surgery |

| MMC | Mitomycin C |

| TGFα | Transforming growth factor-alpha |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PF4 | Platelet Factor 4 |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| PAMP | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PRR | Pattern-recognition receptors |

| NETs | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| TNFα | Tumour-necrosis factor-alpha |

| IL | Interleukins |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1 |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| JNK | c-Jun-N-terminal kinase |

| SPARC | Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| EC | Endothelial cells |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| FGF-2 | Fibroblast growth factor-2 |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| VPA | Valproic acid |

| ROCK | Rho-associated protein kinases |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| TAZ | Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

References

- Tham, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.-Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden through 2040: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Briant, P.S.; Flaxman, S.R.; Taylor, H.R.B.; Jonas, J.B.; Abdoli, A.A.; Abrha, W.A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.G.; et al. Causes of Blindness and Vision Impairment in 2020 and Trends over 30 Years, and Prevalence of Avoidable Blindness in Relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e144–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.S.; Francis, B.A.; Weinreb, R.N. Structural and Functional Imaging of Aqueous Humor Outflow. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 46, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, G.; Saraswathy, S.; Bogarin, T.; Pan, X.; Barron, E.; Wong, T.T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Hong, Y.; Huang, A.S. Functional, Structural, and Molecular Identification of Lymphatic Outflow from Subconjunctival Blebs. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 196, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-A.; Mitchell, W.; Hall, N.; Elze, T.; Lorch, A.C.; Miller, J.W.; Zebardast, N.; Pershing, S.; Hyman, L.; Haller, J.A.; et al. Trends and Usage Patterns of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery in the United States: IRIS® Registry Analysis 2013–2018. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2021, 4, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarz Barberá, M.; Martínez-Galdón, F.; Caballero-Magro, E.; Rodríguez-Piñero, M.; Tañá-Rivero, P. Efficacy and Safety of the Preserflo Microshunt With Mitomycin C for the Treatment of Open Angle Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2022, 31, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, B.; Patel, M.; Suresh, S.; Ginjupalli, M.; Surya, A.; Albdour, M.; Kooner, K.S. Wound Modulations in Glaucoma Surgery: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, D.Y.; Lovicu, F.J. Myofibroblast Transdifferentiation: The Dark Force in Ocular Wound Healing and Fibrosis. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 60, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-D.; Li, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, J. Mechanisms of Fibrosis Formation Following Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 18, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 665–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titus, A.; Marappa-Ganeshan, R. Physiology, Endothelin. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker, D.; Dhamoon, A.S. Physiology, Thromboxane A2. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khaw, P.T.; Bouremel, Y.; Brocchini, S.; Henein, C. The Control of Conjunctival Fibrosis as a Paradigm for the Prevention of Ocular Fibrosis-Related Blindness. “Fibrosis Has Many Friends”. Eye 2020, 34, 2163–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Crowston, J.G.; Cordeiro, M.F.; Akbar, A.N.; Khaw, P.T. The Role of the Immune System in Conjunctival Wound Healing after Glaucoma Surgery. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000, 45, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlunck, G.; Meyer-ter-Vehn, T.; Klink, T.; Grehn, F. Conjunctival Fibrosis Following Filtering Glaucoma Surgery. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 142, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M.F.; Chang, L.; Lim, K.S.; Daniels, J.T.; Pleass, R.D.; Siriwardena, D.; Khaw, P.T. Modulating Conjunctival Wound Healing. Eye 2000, 14 Pt 3B, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, S.; Lei, V.; MacLeod, A.S. The Cutaneous Wound Innate Immunological Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from Inflammation to Proliferation: A Critical Step during Wound Healing. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Schloss, R.; Palmer, A.; Berthiaume, F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-Wound Healing Phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, O.; Kitano-Izutani, A.; Tomoyose, K.; Reinach, P.S. Pathobiology of Wound Healing after Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015, 15 (Suppl. S1), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchi, M.; Tomaselli, D.; Ruggeri, M.L.; Aiello, F.B.; Sabella, P.; Dore, S.; Pinna, A.; Mastropasqua, R.; Nubile, M.; Agnifili, L. Fighting Bleb Fibrosis After Glaucoma Surgery: Updated Focus on Key Players and Novel Targets for Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, L.K.; Sherwood, M.B.; Kahook, M.Y. Wound Modulation after Filtration Surgery. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2012, 57, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, D.C.; Grierson, I.; Stürmer, J.; Hitchings, R.A. Reversal of Topical Antiglaucoma Medication Effects on the Conjunctiva. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1996, 114, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, O.S.; Sim, J.J.L.; Htoon, H.M.; Chew, A.C.Y.; Chong, R.S.; Husain, R.; Perera, S.; Wong, T.T. Study of Effects of Topical Fluorometholone on Tear MCP-1 in Eyes Undergoing Trabeculectomy: Effect on Early Trabeculectomy Outcomes in Asian Glaucoma Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersey, J.P.; Broadway, D.C. Corticosteroid-Induced Glaucoma: A Review of the Literature. Eye 2006, 20, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.J.L.; Man, R.E.K.; Foo, R.C.M.; Huang, O.S.; Betzler, B.K.; Husain, R.; Ho, C.L.; Boey, P.Y.; Perera, S.A.; Low, J.R.; et al. Oral Ibuprofen Is Associated With Reduced Likelihood of Early Bleb Failure After Trabeculectomy in High-Risk Glaucoma Patients. J. Glaucoma 2023, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.R.; Bevin, T.H.; Molteno, A.C.B.; Vote, B.J.T.; Herbison, P. Anti-Inflammatory Fibrosis Suppression in Threatened Trabeculectomy Bleb Failure Produces Good Long Term Control of Intraocular Pressure without Risk of Sight Threatening Complications. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 1352–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breusegem, C.; Spielberg, L.; Van Ginderdeuren, R.; Vandewalle, E.; Renier, C.; Van de Veire, S.; Fieuws, S.; Zeyen, T.; Stalmans, I. Preoperative Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug or Steroid and Outcomes after Trabeculectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, D.; Buys, Y.; Jin, Y.-P.; Alasbali, T.; Smith, M.; Trope, G.E. Corticosteroids versus NSAIDs on Intraocular Pressure and the Hypertensive Phase after Ahmed Glaucoma Valve Surgery. J. Glaucoma 2011, 20, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearza, A.A.; Aslanides, I.M. Uses and Complications of Mitomycin C in Ophthalmology. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2007, 6, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowston, J.G.; Akbar, A.N.; Constable, P.H.; Occleston, N.L.; Daniels, J.T.; Khaw, P.T. Antimetabolite-Induced Apoptosis in Tenon’s Capsule Fibroblasts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998, 39, 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, V.H.X.; Htoon, H.M.; Welsbie, D.S.; Perera, S.A. Aqueous Shunts with Mitomycin C versus Aqueous Shunts Alone for Glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD011875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-C.; Yang, S.; Hribar, M.R.; Chen, A. Mitomycin C in Ahmed Glaucoma Valve Implant Affects Surgical Outcomes. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occleston, N.L.; Daniels, J.T.; Tarnuzzer, R.W.; Sethi, K.K.; Alexander, R.A.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Schultz, G.S.; Khaw, P.T. Single Exposures to Antiproliferatives: Long-Term Effects on Ocular Fibroblast Wound-Healing Behavior. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997, 38, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study Group. Five-Year Follow-up of the Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 121, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, M.; Indar, A.; Wormald, R. Intraoperative Mitomycin C for Glaucoma Surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2005, CD002897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquale, L.R.; Dorman-Pease, M.E.; Lutty, G.A.; Quigley, H.A.; Jampel, H.D. Immunolocalization of TGF-Beta 1, TGF-Beta 2, and TGF-Beta 3 in the Anterior Segment of the Human Eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993, 34, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, M.F.; Gay, J.A.; Khaw, P.T. Human Anti-Transforming Growth Factor-Beta2 Antibody: A New Glaucoma Anti-Scarring Agent. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999, 40, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, A.L.; Wong, T.T.L.; Cordeiro, M.F.; Anderson, I.K.; Khaw, P.T. Evaluation of Anti-TGF-Beta2 Antibody as a New Postoperative Anti-Scarring Agent in Glaucoma Surgery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 3394–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAT-152 0102 Trabeculectomy Study Group. A Phase III Study of Subconjunctival Human Anti–Transforming Growth Factor Β2 Monoclonal Antibody (CAT-152) to Prevent Scarring after First-Time Trabeculectomy. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1822–1830.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.R.; Cheng, Q.; Lee, D.A. Basic Science and Clinical Aspects of Wound Healing in Glaucoma Filtering Surgery. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 14, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Van Bergen, T.; Van De Veire, S.; Van De Vel, I.; Moreau, H.; Dewerchin, M.; Maudgal, P.C.; Zeyen, T.; Spileers, W.; Moons, L.; et al. Inhibition of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Reduces Scar Formation after Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, J.A.; Mullany, S.; Craig, J.E. Intravitreal Bevacizumab Improves Trabeculectomy Survival at 12 Months: The Bevacizumab in Trabeculectomy Study—A Randomised Clinical Trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 108, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.S.; Jain, R.; Kumar, H.; Grewal, S.P.S. Evaluation of Subconjunctival Bevacizumab as an Adjunct to Trabeculectomy a Pilot Study. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 2141–2145.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J.F.; Constable, P.H.; Murdoch, I.E.; Khaw, P.T. Beta Irradiation: New Uses for an Old Treatment: A Review. Eye 2003, 17, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, P.H.; Crowston, J.G.; Occleston, N.L.; Khaw, P.T. The Effects of Single Doses of β Radiation on the Wound Healing Behaviour of Human Tenon’s Capsule Fibroblasts. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 88, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J.F.; Rennie, C.; Evans, J.R. Beta Radiation for Glaucoma Surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD003433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, L.-F.; Toh, L.Z.; Finger, S.N.; Chu, S.W.L.; Stefanovic, B.; Wong, T.T. Valproic Acid Suppresses Collagen by Selective Regulation of Smads in Conjunctival Fibrosis. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 94, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seet, L.-F.; Yap, Z.L.; Chu, S.W.L.; Toh, L.Z.; Ibrahim, F.I.; Teng, X.; Wong, T.T. Effects of Valproic Acid and Mitomycin C Combination Therapy in a Rabbit Model of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, P.F.; Gunawan, M.; Yap, Z.L.; Leong, C.; Kwek, F.; Varadarajan, J.; Wang, X.; Kageyama, M.; Wong, T.T. Valproic Acid Application to Modify Post Surgical Fibrosis in a Model of Minimally Invasive Bleb Surgery. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Dang, Y. Rho-Kinase Inhibitors as Emerging Targets for Glaucoma Therapy. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 2943–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futakuchi, A.; Inoue, T.; Fujimoto, T.; Inoue-Mochita, M.; Kawai, M.; Tanihara, H. The Effects of Ripasudil (K-115), a Rho Kinase Inhibitor, on Activation of Human Conjunctival Fibroblasts. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 149, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Qian, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. SPARC-YAP/TAZ Inhibition Prevents the Fibroblasts-Myofibroblasts Transformation. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 429, 113649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seet, L.-F.; Su, R.; Toh, L.Z.; Wong, T.T. In Vitro Analyses of the Anti-Fibrotic Effect of SPARC Silencing in Human Tenon’s Fibroblasts: Comparisons with Mitomycin C. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, L.F.; Tan, Y.F.; Toh, L.Z.; Chu, S.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Venkatraman, S.S.; Wong, T.T. Targeted Therapy for the Post-Operative Conjunctiva: SPARC Silencing Reduces Collagen Deposition. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Geng, X.; Guo, Z.; Chu, D.; Liu, R.; Cheng, B.; Cui, H.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Li, Z. M2 Macrophages Promote Subconjunctival Fibrosis through YAP/TAZ Signalling. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2313680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Tam, A.L.C.; Campbell, R.; Renwick, N. Emerging Evidence of Noncoding RNAs in Bleb Scarring after Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Cells 2022, 11, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, C.; Li, G.; Huang, J.; Qiu, J.; Wu, J.; Yuan, F.; Epstein, D.L.; Gonzalez, P. Regulation of Trabecular Meshwork Cell Contraction and Intraocular Pressure by miR-200c. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Fu, Y.; Tong, J.; Fan, S.; Xu, K.; Sun, H.; Liang, Y.; Yan, C.; Yuan, Z.; Ge, Y. MicroRNA-216b/Beclin 1 Axis Regulates Autophagy and Apoptosis in Human Tenon’s Capsule Fibroblasts upon Hydroxycamptothecin Exposure. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 123, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Jiang, K.; Meng, K.; Liu, W.; Liu, P.; Du, Y.; Wang, D. TGF-Β2 Induces Proliferation and Inhibits Apoptosis of Human Tenon Capsule Fibroblast by miR-26 and Its Targeting of CTGF. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 104, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Cui, J.; Duan, X.; Chen, H.; Fan, F. Suppression of Type I Collagen Expression by miR-29b via PI3K, Akt, and Sp1 Pathway in Human Tenon’s Fibroblasts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Hou, S.-Y.; Tong, B.-D.; Yin, J.-Y.; Xiong, W. The Smad2/3/4 Complex Binds miR-139 Promoter to Modulate TGFβ-Induced Proliferation and Activation of Human Tenon’s Capsule Fibroblasts through the Wnt Pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 13342–13352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Park, C.K. Visual Field Progression Is Associated with Systemic Concentration of Macrophage Chemoattractant Protein-1 in Normal-Tension Glaucoma. Curr. Eye Res. 2017, 42, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Qian, T.; Gong, Q.; Fu, M.; Bian, X.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X. Inflammatory Cytokines Levels in Aqueous Humour and Surgical Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Patients with Prior Acute Primary Angle Closure. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, e1106–e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, R.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Chu, S.W.L.; Toh, L.Z.; Wong, T.T.L. Inhibition of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 Prevents Conjunctival Fibrosis in an Experimental Model of Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 3432–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.T.; Kiew, S.Y.; Toh, L.Z.; Chu, S.; Zanardi, M.; Deng, Q.; Wang, X.; Wong, T.T. Inhibition of Chemokine MCP-1 with mNOX-E36 Reduces Scarring in a Mouse Model of Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 262, 110735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Schwartz, T.D.; Lawrence, E.C.N.; Lu, J.; Zhong, A.; Wu, J.; Sterling, J.K.; Nikonov, S.; Dunaief, J.L.; Cui, Q.N. Loss of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Reduced Monocyte Recruitment and Preserved Retinal Ganglion Cells in a Mouse Model of Hypertensive Glaucoma. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 254, 110325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.T.L.; Mead, A.L.; Khaw, P.T. Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibition Modulates Postoperative Scarring after Experimental Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, W.; Han, K.E.; Han, J.R. Safety of Using Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitor in Experimental Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, E.; Balikoglu-Yilmaz, M.; Bozdag-Pehlivan, S.; Sungu, N.; Aksakal, F.N.; Altinok, A.; Tuna, T.; Unlu, N.; Ustun, H.; Koklu, G.; et al. Effect of Doxycycline on Postoperative Scarring After Trabeculectomy in an Experimental Rabbit Model. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 26, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Ahmed, A.H.A.; Lockwood, A.; Li, H.; Bailly, M.; Khaw, P.T.; Brocchini, S. An Ilomastat-CD Eye Drop Formulation to Treat Ocular Scarring. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 3425–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Therapeutic Agents | Molecular Target | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Potential Risks | Stage of Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ antibody [38,39,40] | Inhibits TGFβ | Reduces fibroblast proliferation and migration | Greater specificity | Mild corneal staining | Phase III clinical trial of CAT-152 failed to show a significant difference |

| VEGF antibody [42,43,44] | Inhibits VEGF | Inhibits fibroblast proliferation, reduces angiogenesis and collagen deposition | Greater specificity | Avascular blebs, bleb-related complications, hypotony | Longer term randomised clinical trial required |

| Beta radiation [45,46] | Increases p53 | Inhibits fibroblast proliferation alter ECM production | Low cost, long service life | Cataract formation, keratopathy | More safety and efficacy data required |

| Valproic acid [49,50] | Inhibits type 1 collagen | Suppresses pro-fibrotic Smad2/3/4 signalling, promotes anti-fibrotic Smad6 pathway | Also acts on collagen, resulting in a more favourable bleb morphology | None noted to date | In vivo studies on mouse and rabbit models of GFS have shown promising results |

| ROCK inhibitor [51,52] | Rho-kinase | Alters myoglobin/actin contraction, inhibits fibroblast proliferation | Greater specificity | Conjunctival hyperaemia, blepharitis, keratopathy | In vivo studies have shown promising results |

| SPARC siRNA [54,55] | Suppress SPARC expression | Suppresses fibroblast proliferation, less collagenous ECM | Improves bleb survival, no cellular toxicity | None noted to date | In vivo studies on mouse and rabbit models of GFS have shown promising results |

| YAP/TAZ signalling inhibitor [56] | M2 macrophages | Activates Smad 2/3, mediates TGFβ1/2 | Greater specificity | None noted to date | In vitro studies inconclusive |

| miRNA mimics or anti-miRNA [57] | miRNA | Different miRNAs have pro- or anti-fibrotic effects | Selectively target genes | Unintended effect on other genes/limited impact on target genes | Mostly studies conducted in vitro on human Tenon’s fibroblasts |

| MCP-1 inhibitors [65,66] | CCR2 receptor antagonist or MCP-1 aptamer | Inhibits MCP-1 activity | Improves bleb survival, less cellular toxicity | None noted to date | In vivo studies on mouse models of GFS show promising results |

| MMP inhibitor [68,69,70,71] | MMP | Degrades ECM | Improves bleb survival, reduces scar tissue | Mild conjunctival toxicity | In vivo studies on rabbit models of GFS show promising results |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lo, P.F.; Lim, S.T.; Wang, X.; Wong, T.T. Current Challenges of Managing Fibrosis Post Glaucoma Surgery and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238548

Lo PF, Lim ST, Wang X, Wong TT. Current Challenges of Managing Fibrosis Post Glaucoma Surgery and Future Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238548

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo, Phey Feng, Seok Ting Lim, Xiaomeng Wang, and Tina T. Wong. 2025. "Current Challenges of Managing Fibrosis Post Glaucoma Surgery and Future Perspectives" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238548

APA StyleLo, P. F., Lim, S. T., Wang, X., & Wong, T. T. (2025). Current Challenges of Managing Fibrosis Post Glaucoma Surgery and Future Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238548