Development of an Algorithm to Assist in the Diagnosis of Combined Retinal Vein Occlusion and Glaucoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of a Comprehensive Fundus Disease Diagnostic Artificial Intelligence Algorithm (CD-AI)

2.2. Enrollment Criteria for Fundus Images

2.3. Development of an Algorithm for Diagnosing Glaucoma in Eyes with Concomitant RVO (RVO-GLA AI)

2.4. Training and Validation of the RVO-GLA AI

3. Results

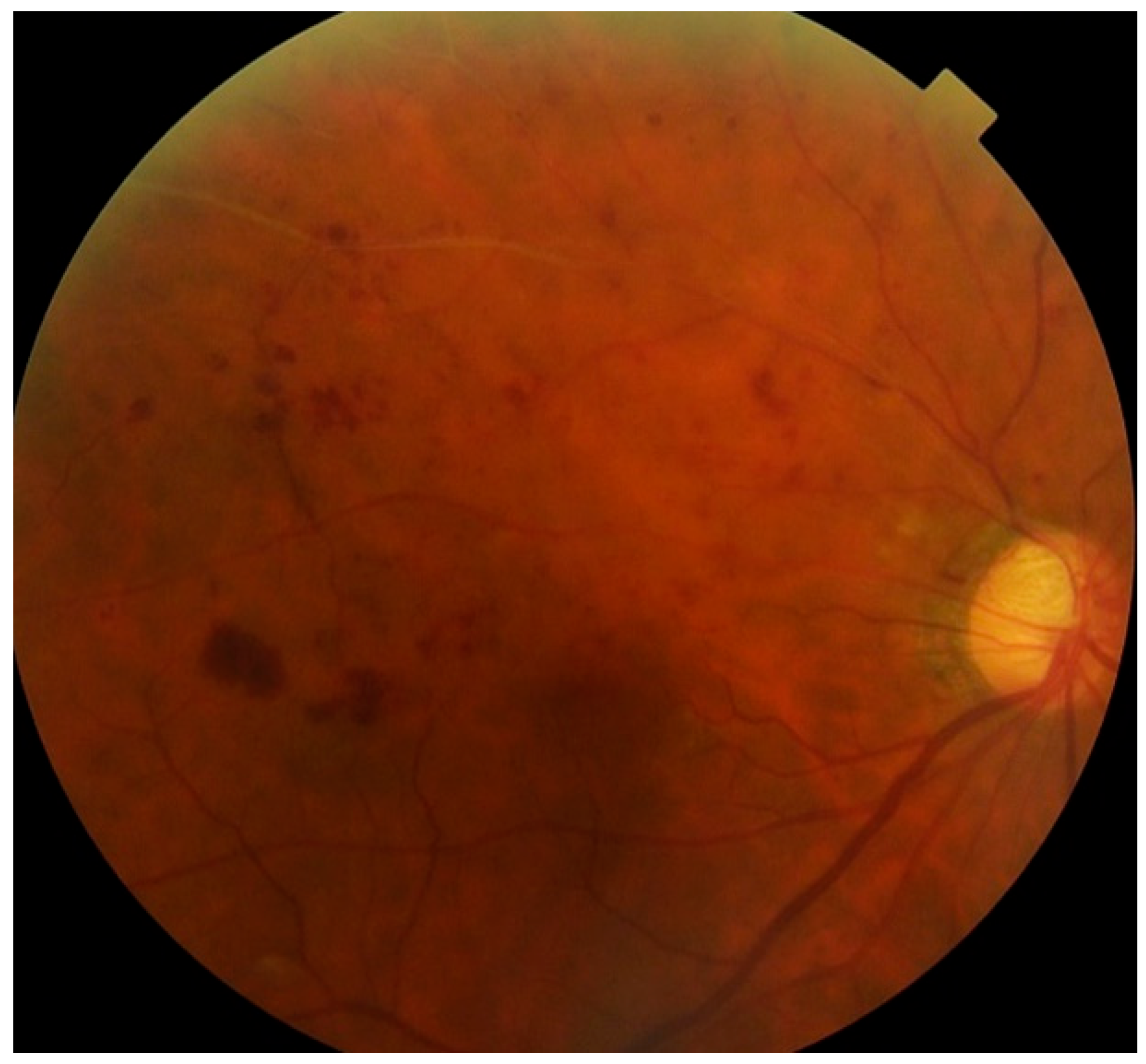

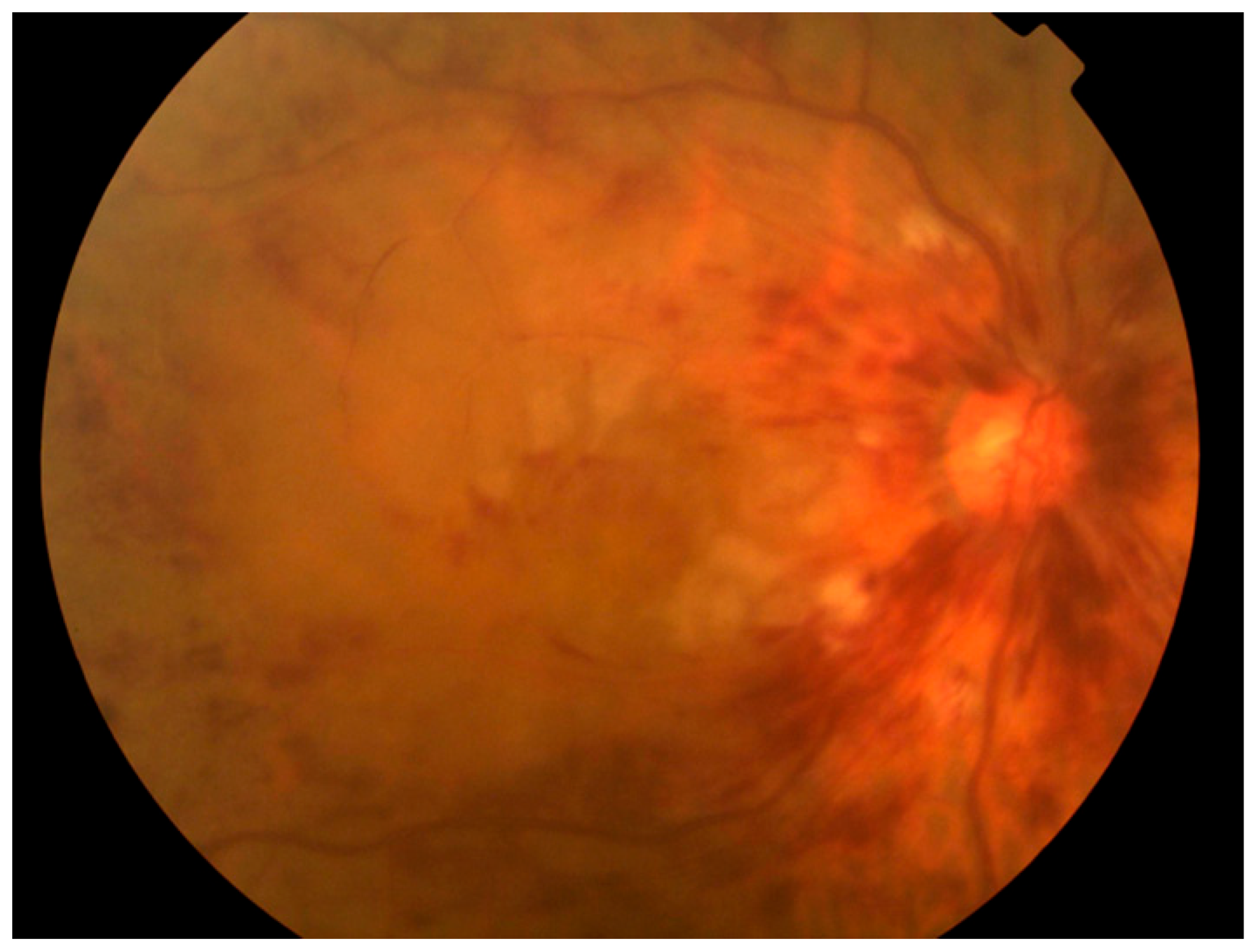

3.1. Diagnostic Accuracy of the CD-AI for Glaucoma in Eyes with or Without RVO

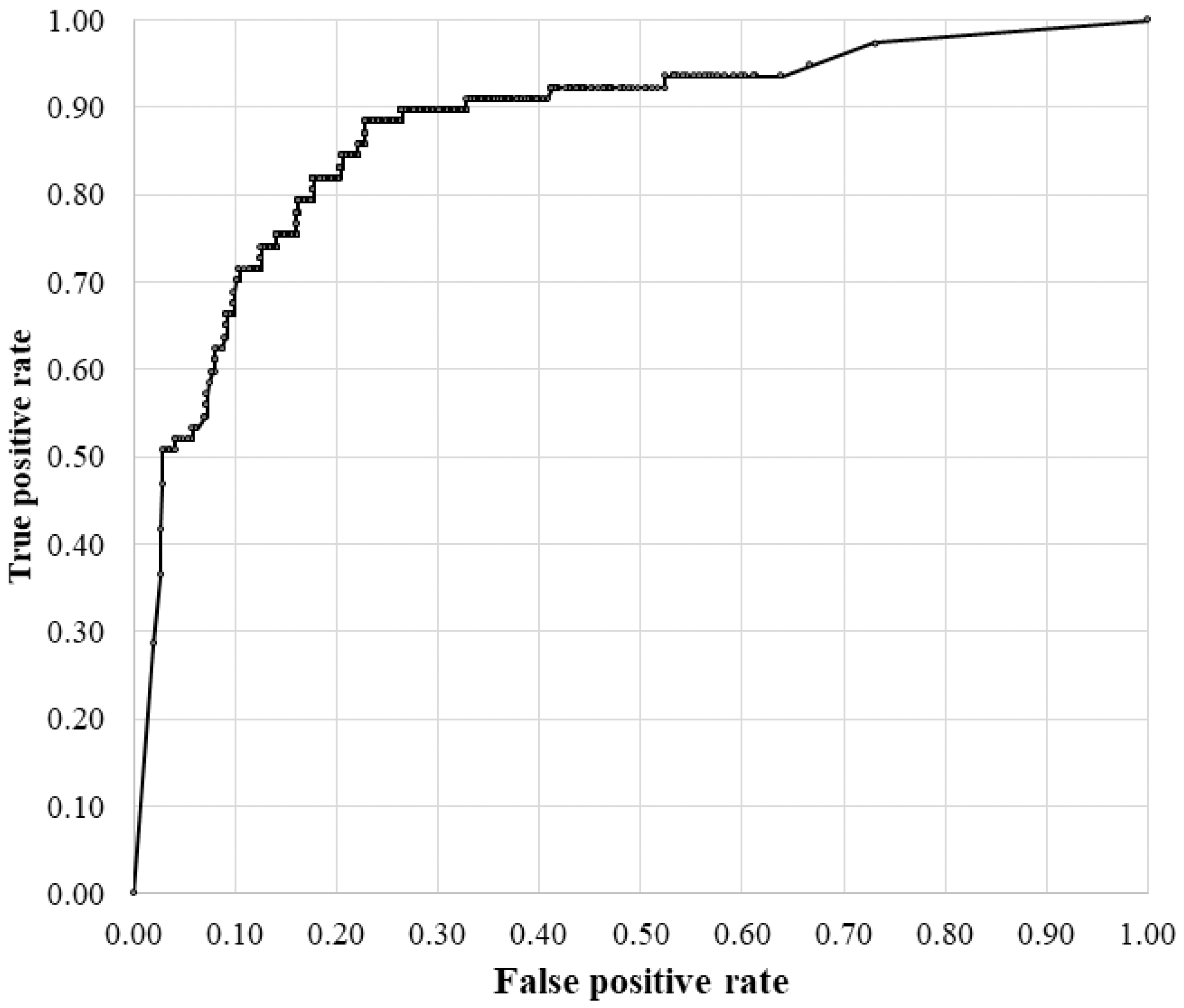

3.2. Diagnostic Accuracy of the RVO-GLA AI

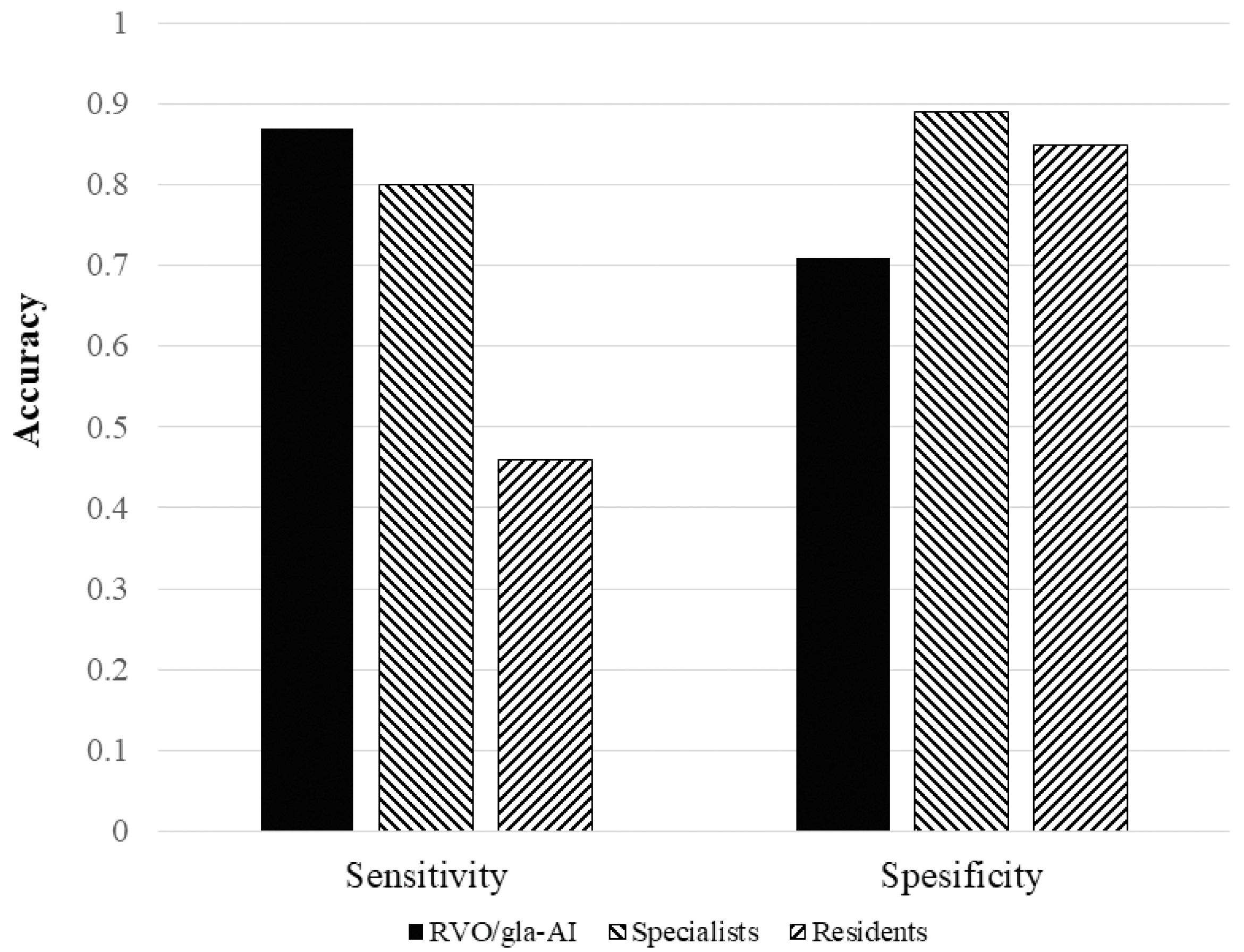

3.3. Comparison of the RVO-GLA AI with Ophthalmologists

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quigley, H.A. Number of People with Glaucoma Worldwide. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 80, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden Through 2040: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, S.; Satoh, S.; Yoda, Y.; Kashiwagi, K.; Oshika, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Miyake, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Yoshitomi, T.; Inatani, M.; et al. Evaluation of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Glaucoma Detection. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 63, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, Y.; Keel, S.; Meng, W.; Chang, R.T.; He, M. Efficacy of a Deep Learning System for Detecting Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy Based on Color Fundus Photographs. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammal, A.A.; Thompson, A.C.; Mariottoni, E.B.; Berchuck, S.I.; Urata, C.N.; Estrela, T.; Wakil, S.M.; Costa, V.P.; Medeiros, F.A. Human versus Machine: Comparing a Deep Learning Algorithm to Human Gradings for Detecting Glaucoma on Fundus Photographs. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 211, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, N.; Tanito, M.; Mitsuhashi, K.; Fujino, Y.; Matsuura, M.; Murata, H.; Asaoka, R. Development of a Deep Residual Learning Algorithm to Screen for Glaucoma from Fundus Photography. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, Y.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Chen, Y.H. Deep Learning Evaluation of Glaucoma Detection Using Fundus Photographs in Highly Myopic Populations. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemelings, R.; Elen, B.; Barbosa-Breda, J.; Blaschko, M.B.; De Boever, P.; Stalmans, I. Deep Learning on Fundus Images Detects Glaucoma Beyond the Optic Disc. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.C.; Chen, H.S.; Yeh, P.H.; Cheng, Y.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Shen, S.C.; Lee, Y.S. Deep Learning in Glaucoma Detection and Progression Prediction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noury, E.; Mannil, S.S.; Chang, R.T.; Ran, A.R.; Cheung, C.Y.; Thapa, S.S.; Rao, H.L.; Dasari, S.; Riyazuddin, M.; Chang, D.; et al. Deep Learning for Glaucoma Detection and Identification of Novel Diagnostic Areas in Diverse Real-World Datasets. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, M.; Kiyohara, Y.; Arakawa, S.; Hata, Y.; Yonemoto, K.; Doi, Y.; Iida, M.; Ishibashi, T. Prevalence and Systemic Risk Factors for Retinal Vein Occlusion in a General Japanese Population: The Hisayama Study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 3205–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.K.; Moss, S.E.; Meuer, S.M. The Epidemiology of Retinal Vein Occlusion: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2000, 98, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Lu, P. Association of Glaucoma with Risk of Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019, 97, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.L.; McIntosh, R.L.; Lim, L.; Mitchell, P.; Cheung, N.; Kowalski, J.W.; Nguyen, H.P.; Wang, J.J.; Wong, T.Y. Natural History of Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion: An Evidence-Based Systematic Review. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1094–1101.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshika, T.; Hiraoka, T.; Kawana, K.; Fukuda, S.; Ueno, Y.; Hoshi, T.; Tasaki, K.; Mori, Y.; Kiuchi, G.; Yasuno, Y.; et al. Digital Ophthalmology—From Its Dawn to Golden Age. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi (Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. Soc.) 2023, 127, 257–296. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasai, H.; Kitamura, K.; Hasebe, Y.; Mizutani, J.; Utsunomiya, K.; Sato, S.; Murao, K.; Ninomiya, Y.; Mori, K.; Kawase, K.; et al. Development of an Algorithm to Assist in the Diagnosis of Combined Retinal Vein Occlusion and Glaucoma. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238547

Kasai H, Kitamura K, Hasebe Y, Mizutani J, Utsunomiya K, Sato S, Murao K, Ninomiya Y, Mori K, Kawase K, et al. Development of an Algorithm to Assist in the Diagnosis of Combined Retinal Vein Occlusion and Glaucoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238547

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasai, Hiroshi, Kazuyoshi Kitamura, Yuka Hasebe, Junya Mizutani, Kengo Utsunomiya, Shiori Sato, Kohei Murao, Yoichiro Ninomiya, Kensaku Mori, Kazuhide Kawase, and et al. 2025. "Development of an Algorithm to Assist in the Diagnosis of Combined Retinal Vein Occlusion and Glaucoma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238547

APA StyleKasai, H., Kitamura, K., Hasebe, Y., Mizutani, J., Utsunomiya, K., Sato, S., Murao, K., Ninomiya, Y., Mori, K., Kawase, K., Tanito, M., Nakazawa, T., Miki, A., Mori, K., Yoshitomi, T., & Kashiwagi, K. (2025). Development of an Algorithm to Assist in the Diagnosis of Combined Retinal Vein Occlusion and Glaucoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238547