Time to Decompression in Obstructive Urosepsis from Ureteral Calculi: Thresholds, Initial Diversion, and Early Biomarkers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol, PICO Statement, and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Dates

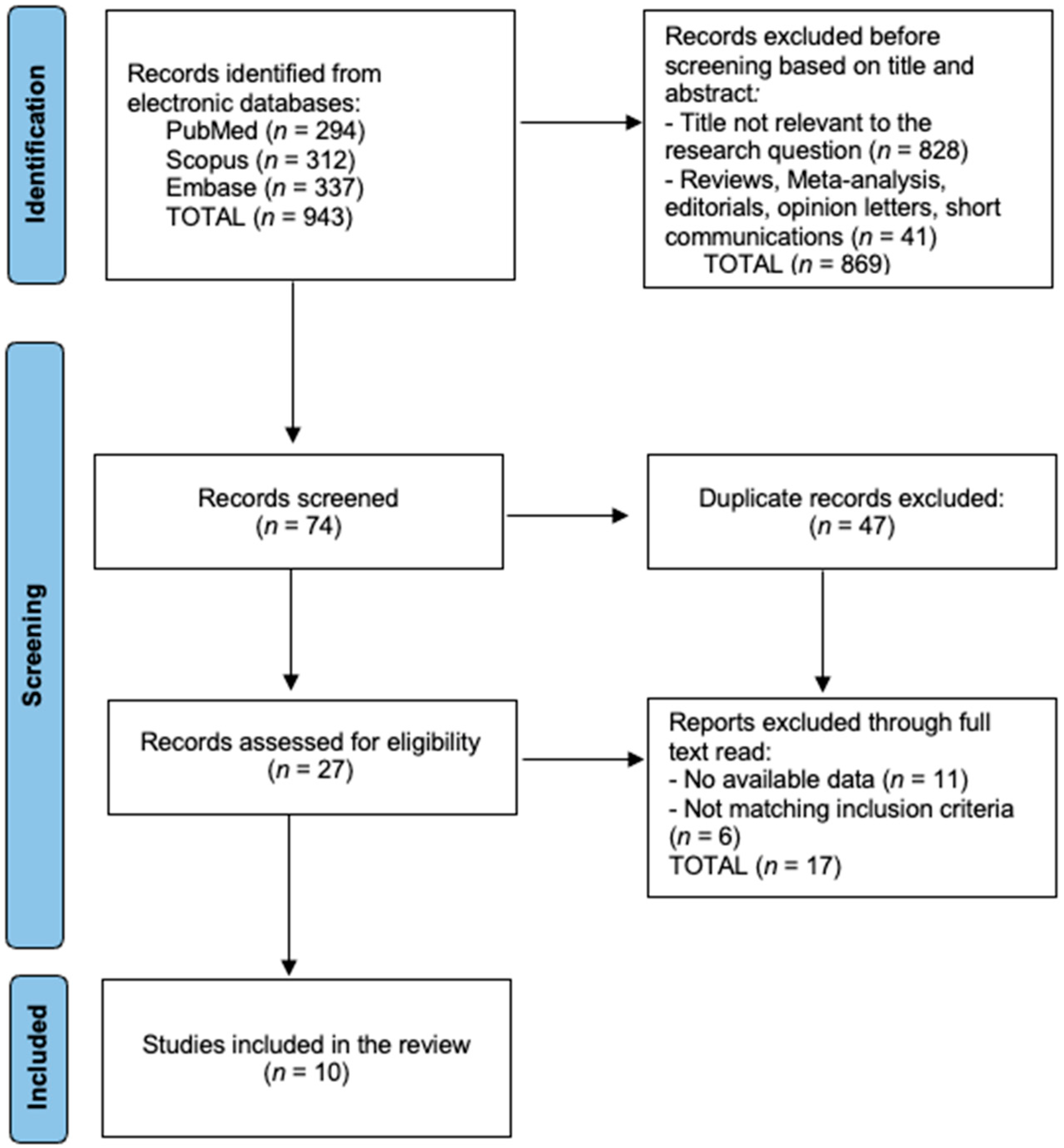

2.3. Study Selection and PRISMA Flow

2.4. Data Items and Extraction

2.5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akram, M.; Jahrreiss, V.; Skolarikos, A.; Geraghty, R.; Tzelves, L.; Emilliani, E.; Davis, N.F.; Somani, B.K. Urological Guidelines for Kidney Stones: Overview and Comprehensive Update. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensiv. Care Med. 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reitz, K.M.; Kennedy, J.; Li, S.R.; Handzel, R.; Tonetti, D.A.; Neal, M.D.; Zuckerbraun, B.S.; Hall, D.E.; Sperry, J.L.; Angus, D.C.; et al. Association Between Time to Source Control in Sepsis and 90-Day Mortality. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Del Giudice, F.; Yoo, K.H.; Lee, S.; Oh, J.K.; Cho, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Min, G.E.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, W.; Li, S.; et al. Characteristics of Sepsis or Acute Pyelonephritis Combined with Ureteral Stone in the United States: A Retrospective Analysis of Large National Cohort. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.J.; Jun, D.Y.; Jeong, J.Y.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, H.D. Percutaneous Nephrostomy versus Ureteral Stent for Severe Urinary Tract Infection with Obstructive Urolithiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2024, 60, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cardoso, A.; Coutinho, A.; Neto, G.; Anacleto, S.; Tinoco, C.L.; Morais, N.; Cerqueira-Alves, M.; Lima, E.; Mota, P. Percutaneous nephrostomy versus ureteral stent in hydronephrosis secondary to obstructive urolithiasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Urol. 2024, 11, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, T.; Liu, S.; Ding, G.; Mao, Q.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wu, J. Meta-analysis of perioperative outcomes and safety of percutaneous nephrostomy versus retrograde ureteral stenting in the treatment of acute obstructive upper urinary tract infection. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2024, 16, 17562872241241854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Orr, A.; Awad, M.; Johnson, N.; Sternberg, K. Obstructing Ureteral Calculi and Presumed Infection: Impact of Antimicrobial Duration and Time from Decompression to Stone Treatment in Developing Urosepsis. Urology 2023, 172, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.; Kim, B.S.; Ha, Y.-S.; Chung, J.-W.; Jang, G.; Noh, M.-G.; Ahn, H.B.; Lee, J.N.; Kim, H.T.; Yoo, E.S.; et al. Predicting septic shock in obstructive pyelonephritis associated with ureteral stones: A retrospective study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Niu, K.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-B.; Yen, C.-C. Development of a Predictive Nomogram for Sepsis in Patients with Urolithiasis-Related Obstructive Pyelonephritis. Medicina 2024, 60, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsaraya, N.; Gordon-Irshai, A.; Schwarzfuchs, D.; Novack, V.; Mabjeesh, N.J.; Neulander, E.Z. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as an early indicator for ureteral catheterization in patients with renal colic due to upper urinary tract lithiasis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kamei, J.; Nishimatsu, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Suzuki, M.; Fujimura, T.; Fukuhara, H.; Igawa, Y.; Kume, H.; Homma, Y. Risk factors for septic shock in acute obstructive pyelonephritis requiring emergency drainage of the upper urinary tract. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2014, 46, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belyayeva, M.; Leslie, S.W.; Jeong, J.M. Acute Pyelonephritis. [Updated 2024 Feb 28]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519537/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Boeri, L.; Fulgheri, I.; Palmisano, F.; Lievore, E.; Lorusso, V.; Ripa, F.; D’Amico, M.; Spinelli, M.G.; Salonia, A.; Carrafiello, G.; et al. Hounsfield unit attenuation value can differentiate pyonephrosis from hydronephrosis and predict septic complications in patients with obstructive uropathy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Early diagnostic model of pyonephrosis with calculi based on radiomic features combined with clinical variables. Biomed. Eng. Online 2024, 23, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haas, C.R.; Li, G.; Hyams, E.S.; Shah, O. Delayed Decompression of Obstructing Stones with Urinary Tract Infection is Associated with Increased Odds of Death. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, R.H.; Barton, G.J.; Kothari, A.N.; Zapf, M.A.; Flanigan, R.C.; Kuo, P.C.; Gupta, G.N. Early Intervention during Acute Stone Admissions: Revealing “The Weekend Effect” in Urological Practice. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borofsky, M.S.; Walter, D.; Shah, O.; Goldfarb, D.S.; Mues, A.C.; Makarov, D.V. Surgical decompression is associated with decreased mortality in patients with sepsis and ureteral calculi. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Fujita, K.; Nakazawa, S.; Hayashi, T.; Tanigawa, G.; Imamura, R.; Hosomi, M.; Wada, D.; Fujimi, S.; Yamaguchi, S. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for septic shock in patients receiving emergency drainage for acute pyelonephritis with upper urinary tract calculi. BMC Urol. 2012, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambo, M.; Okegawa, T.; Shishido, T.; Higashihara, E.; Nutahara, K. Predictors of septic shock in obstructive acute pyelonephritis. World J. Urol. 2014, 32, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, X.; Zhou, B.; Hu, D.; Ding, Y. Emergency decompression for patients with ureteral stones and SIRS: A prospective randomized clinical study. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mokhmalji, H.; Braun, P.M.; Martinez Portillo, F.J.; Siegsmund, M.; Alken, P.; Köhrmann, K.U. Percutaneous nephrostomy versus ureteral stents for diversion of hydronephrosis caused by stones: A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J. Urol. 2001, 165, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.-H.; Yang, Y.-H.; Zhou, S.; Lv, J.-L. Percutaneous nephrostomy versus retrograde ureteral stent for acute upper urinary tract obstruction with urosepsis. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 27, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, Z.G.; Oredein-McCoy, O.; Gerber, L.; Bañez, L.L.; Sopko, D.R.; Miller, M.J.; Preminger, G.M.; Lipkin, M.E. Emergent ureteric stent vs. percutaneous nephrostomy for obstructive urolithiasis with sepsis: Patterns of use and outcomes from a 15-year experience. BJU Int. 2013, 112, E122–E128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faw, C.; Wan, J.; Hollingsworth, J.M.; Ambani, S.N.; Ghani, K.R.; Roberts, W.W.; Dauw, C.A. Impact of the Timing of Ureteral Stent Placement on Outcomes in Patients with Obstructing Ureteral Calculi and Presumed Infection. J. Endourol. 2019, 33, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, C.R.; Smigelski, M.B.; Sebesta, E.M.; Mobley, D.; Shah, O. Implementation of a Hospital-Wide Protocol Reduces Time to Decompression and Length of Stay in Patients with Stone-Related Obstructive Pyelonephritis with Sepsis. J. Endourol. 2021, 35, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinojosa-Gonzalez, D.E.; Torres-Martinez, M.; Leon, S.U.V.-D.; Galindo-Garza, C.; Roblesgil-Medrano, A.; Alanis-Garza, C.; Gonzalez-Bonilla, E.; Barrera-Juarez, E.; Flores-Villalba, E. Emergent urinary decompression in acute stone-related urinary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Urol. 2023, 16, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, C.; Georgescu, D.; Popescu, R.; Geavlete, B.; Geavlete, P. Double-J stent versus percutaneous nephrostomy for emergency upper urinary tract decompression. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Hajjaj, M.; Sabbagh, A.J.; Al-Hadid, I.; Anan, M.T.; Kazan, M.N.; Aljool, A.A.; Husein, H.A.M.A.; Tallaa, M. Comparison complications rate between double-J ureteral stent and percutaneous nephrostomy in obstructive uropathy due to stone disease:A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ko, Y.H.; Ji, Y.S.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, S.J.; Song, P.H. Procalcitonin determined at emergency department as an early indicator of progression to septic shock in patient with sepsis associated with ureteral calculi. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2016, 42, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tambo, M.; Taguchi, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Okegawa, T.; Fukuhara, H. Presepsin and procalcitonin as predictors of sepsis based on the new Sepsis-3 definitions in obstructive acute pyelonephritis. BMC Urol. 2020, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, T.; Choi, J.; Yoo, K.H. Differences between Risk Factors for Sepsis and Septic Shock in Obstructive Urolithiasis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Itami, Y.; Miyake, M.; Owari, T.; Iwamoto, T.; Gotoh, D.; Momose, H.; Fujimoto, K.; Hirao, S. Optimal timing of ureteroscopic lithotripsy after the initial drainage treatment and risk factors for postoperative febrile urinary tract infection in patients with obstructive pyelonephritis: A retrospective study. BMC Urol. 2021, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tripathy, K.P.; Chaitanya, Y.; Behera, P.K.; Panigrahi, R.; Dash, D.P. Correlation Between Platelet Indices and Severity of Sepsis: A Hospital-Based Prospective Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e82816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, R.M.; Pietropaolo, A.; Villa, L.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Shaw, M.; Veeratterapillay, R.; Rogers, A.; Ventimiglia, E.; Somani, B.K. Post-Ureteroscopy Infections Are Linked to Pre-Operative Stent Dwell Time over Two Months: Outcomes of Three European Endourology Centres. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuan, G.; Cai, L.; Qu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, P.; Chen, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Chu, Q.; et al. Identification of Calculous Pyonephrosis by CT-Based Radiomics and Deep Learning. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria®. Acute Pyelonephritis. 2025 Update. Available online: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69489/narrative (accessed on 2 October 2025).

| Study (Year) | Design | Tool | Overall RoB Judgment | Main Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haas 2020 [17] | Retrospective administrative cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Residual confounding (limited clinical severity data), reliance on ICD coding for exposure, and outcome definitions |

| Blackwell 2016 [18] | Retrospective administrative cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Residual confounding, possible misclassification of infection and TTD, and “weekend effect” not fully explained by measured covariates |

| Borofsky 2013 [19] | Retrospective administrative cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Unmeasured confounding, coding-based identification of sepsis and decompression, and limited clinical granularity |

| Yamamoto 2012 [20] | Single-center retrospective cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Small sample size, potential selection bias, and limited adjustment for confounding |

| Tambo 2014 [21] | Single-center retrospective cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Modest sample size, potential selection bias, and incomplete control for comorbidity and baseline severity |

| Lu 2023 [22] | Prospective randomized clinical trial | RoB 2 | Some concerns | Limited detail on allocation concealment and blinding and relatively small sample size |

| Mokhmalji 2001 [23] | Prospective randomized clinical trial | RoB 2 | Some concerns | Open-label design, small sample size, and unclear details of outcome adjudication |

| Xu 2021 [24] | Prospective observational cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate to serious | Confounding by indication (PCN often used in more severe/anatomically complex cases) and incomplete reporting of adjustment strategy |

| Goldsmith 2013 [25] | Retrospective single-system cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding by indication (PCN in sicker patients), potential selection bias, and missing data |

| Faw 2019 [26] | Retrospective ED cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Small sample, selection bias, and limited adjustment for confounders in timing analyses |

| Study (Year) | Country | Cohort Size | Population/Setting | Primary Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haas 2020 [17] | USA | 311,100 | National inpatient cohort: adults with UTI + obstructing stone | Assess impact of a decompression delay of ≥2 days on mortality and acute comp |

| Blackwell 2016 [18] | USA | 10,301 | State inpatient DB (FL, CA): acute nephrolithiasis with indication for decompression | Assess effect of timely ≤48 h intervention (and “weekend effect”) on mortality |

| Borofsky 2013 [19] | USA | 1712 | Nationwide Inpatient Sample: sepsis + ureteral calculi | Association of surgical decompression with mortality |

| Yamamoto 2012 [20] | Japan | 98 (101 events) | Single-center emergency drainage for obstructive APN with calculi | Describe clinical profile and risk factors for septic shock after drainage |

| Tambo 2014 [21] | Japan | 69 | Single-center obstructive APN | Identify predictors of septic shock |

| Lu 2023 [22] | China | 150 | Prospective RCT: SIRS + ureteral stones; randomized PCN (n = 78) vs. stent (n = 72) | Compare decompression methods; identify urosepsis risk post-decompression |

| Mokhmalji 2001 [23] | Germany | 40 | Prospective RCT: hydronephrosis from stones needing diversion | Compare PCN vs. ureteral stent for urgent diversion (technical success/complications) |

| Xu 2021 [24] | China | 110 | Acute upper urinary obstruction with urosepsis; PCN vs. stent | Compare PCN vs. stent for efficacy/safety in urosepsis |

| Goldsmith 2013 [25] | USA | 130 | 15 yr single-system cohort: obstructive urolithiasis with sepsis | Compare stent vs. PCN: ICU risk, LOS, failure, death |

| Faw 2019 [26] | USA | 48 | Single-center ED cohort: obstructing ureteral stone + ≥2 SIRS; all stented | Evaluate effect of stent timing (≤6–10 h vs. later) on LOS and ICU use |

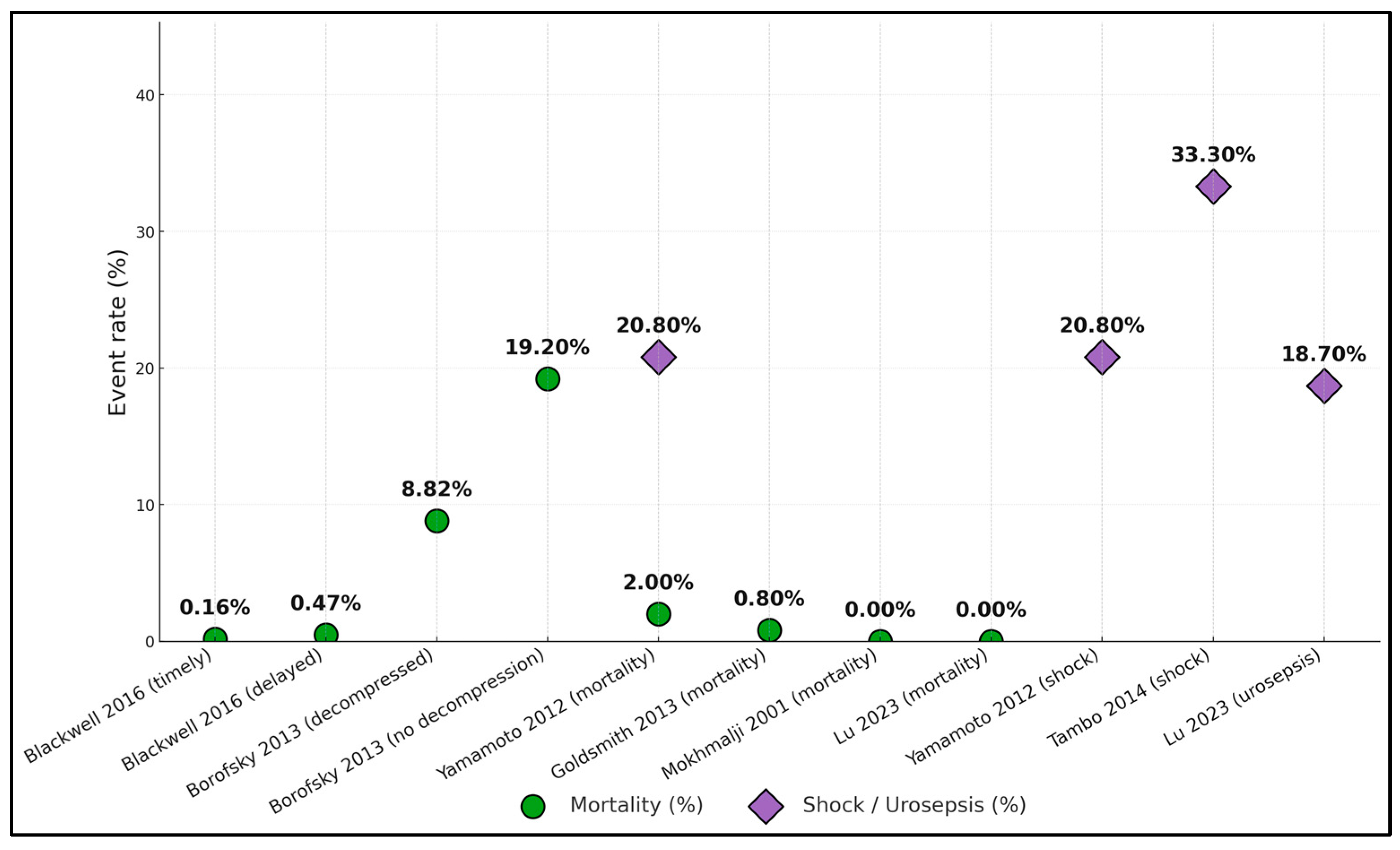

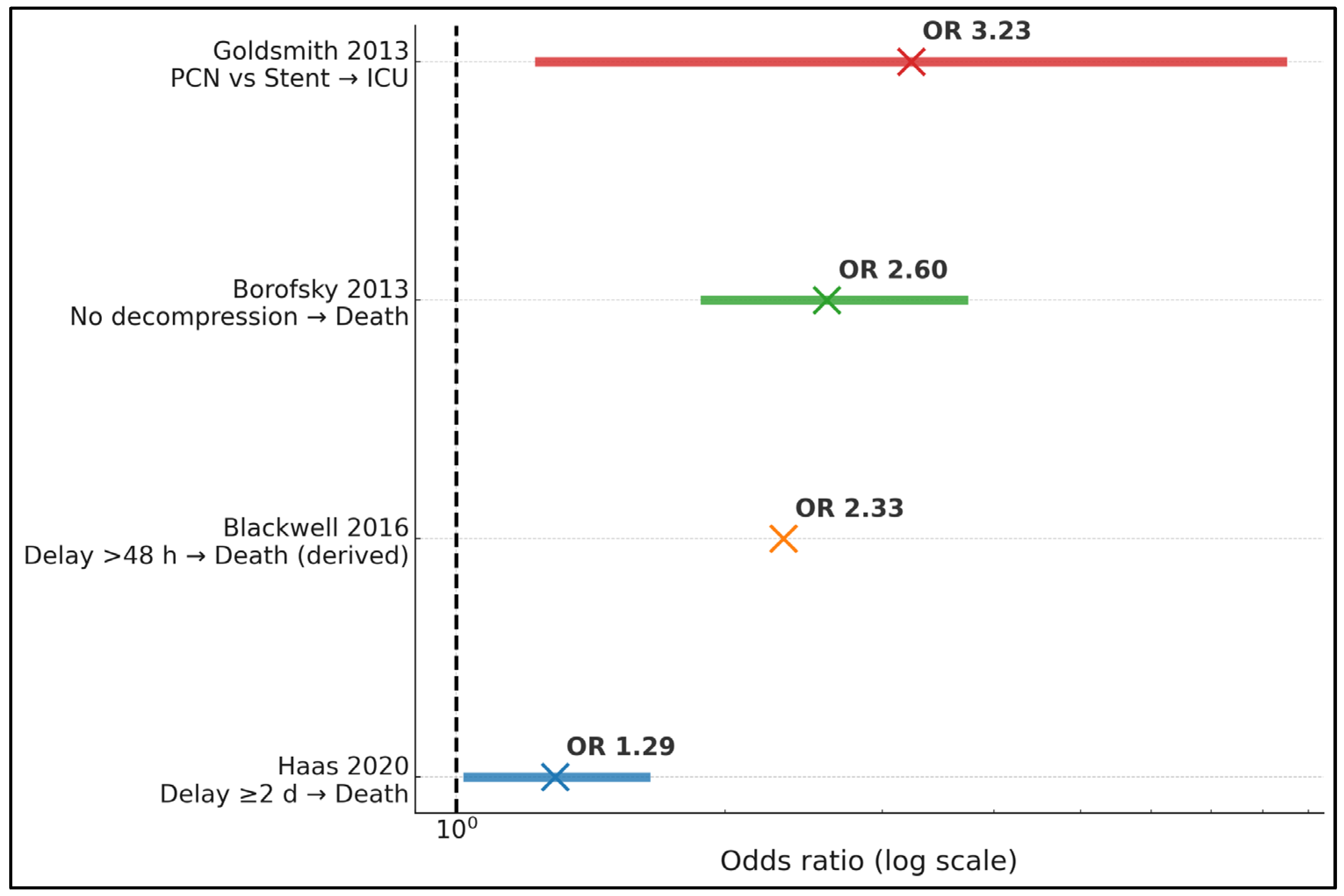

| Study (Year) | Mortality | Septic Shock/Severe Sepsis | ICU Use/Escalation | Length of Stay (LOS) | Other Adjusted Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haas 2020 [17] | In-hospital mortality ↑ with a delay of ≥2 d (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03–1.63) | — | — | — | AKI ↑ with delay (aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03–1.22) |

| Blackwell 2016 [18] | 0.16% timely, ≤48 h, vs. 0.47% delayed; OR, 0.43 for timely (p = 0.044) | — | — | — | Weekend admission ↓ odds of timely by 26% (p < 0.001) |

| Borofsky 2013 [19] | No decompression 19.2% vs. decompression 8.82% (p < 0.001); lack of decompression OR, 2.6 (95% CI, 1.9–3.7) | — | — | — | National sample of 1712 sepsis + stones |

| Yamamoto 2012 [20] | 2 deaths/98 (2.0%) | Septic shock: 21/101 events (20.8%) | Intubation: 12.9% | Median: 11 d overall; 14 d with shock vs. 10 d without (p = 0.008) | Shock group was older; bacteremia 71% vs. 26% (p < 0.001) |

| Tambo 2014 [21] | — | 33% (23/69) septic shock | — | — | Predictors of shock: positive blood culture (59% vs. 18%; OR, 4.8), non-E. coli pathogen (74% vs. 33%; OR, 10.6) |

| Lu 2023 [22] | — | Urosepsis after decompression: 28/150 (18.7%) | — | — | Risk ↑ with pyonephrosis and higher PCT |

| Mokhmalji 2001 [23] | 0% in-hospital deaths (reported) | — | — | — | — |

| Xu 2021 [24] | — | — | — | No sig. LOS difference between PCN and stent (per abstract) | Fever and WBC normalization similar between PCN and stent |

| Goldsmith 2013 [25] | In-hospital deaths: 0.8% overall | — | PCN ↑ ICU odds vs. stent (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.24–8.41) | Longer LOS with PCN (β, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.20–0.74) | PCN cohort was sicker (APACHE II 15 vs. 11) |

| Faw 2019 [26] | — | — | ICU need: no difference by timing | Earlier stent cut LOS: ≤6 h 35.6 h vs. 71.6 h (p = 0.01); ≤10 h 45.7 h vs. 82.4 h (p = 0.04) | 58.3% positive urine culture |

| Study (Year) | TTD Definition/Comparison | Primary Outcome(s) | Effect Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haas 2020 [17] | A delay of ≥2 days vs. <2 days from admission to decompression | In-hospital mortality; acute kidney injury (AKI) | Mortality aOR, 1.29 (95% CI, 1.03–1.63); AKI aOR, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.03–1.22) |

| Blackwell 2016 [18] | Timely intervention, ≤48 h, vs. >48 h during acute stone admission | In-hospital mortality | Mortality, 0.16% vs. 0.47%; OR for timely care, 0.43 (p = 0.044) |

| Borofsky 2013 [19] | Any decompression vs. no decompression in sepsis + ureteral calculi | In-hospital mortality | Mortality, 8.82% with decompression vs. 19.2% without; OR for lack of decompression, 2.6 (95% CI, 1.9–3.7) |

| Faw 2019 [26] | Stent placement ≤ 6 h vs. >6 h from ED arrival | Hospital length of stay (LOS) | Mean LOS, 35.6 h vs. 71.6 h (p = 0.01) |

| Faw 2019 [26] | Stent placement ≤ 10 h vs. >10 h from ED arrival | Hospital LOS | Mean LOS, 45.7 h vs. 82.4 h (p = 0.04) |

| Study (Year) | Decompression Method(s) and Technical Success | Failure/Complication | Microbiology and Labs | Timing/Anatomic Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haas 2020 [17] | — | — | — | A delay of ≥2 days was associated with worse outcomes (see Table 2) |

| Blackwell 2016 [18] | — | — | — | Weekend admission reduced odds of timely, ≤48 h, intervention by 26% |

| Borofsky 2013 [19] | Decompression (stent or PCN) in 78% | — | — | Absence of decompression carried an OR of 2.6 for death |

| Yamamoto 2012 [20] | Stent, 89.1%; PCN, 10.9% | Intubation: 12.9% | Urine culture + 68.3%; bacteremia, 35.6%; CRP median of 16.1 mg/dL | Onset→drainage median, 3 d; stone median, 9 mm; 73.3% ureteral |

| Tambo 2014 [21] | Emergency drainage (mode not primary endpoint) | — | Positive blood culture was more frequent in shock (59% vs. 18%); non-E. coli predominant in shock (74% vs. 33%) | — |

| Lu 2023 [22] | Randomized: PCN, 78 vs. RUSI, 72; PCN success, 100%; RUSI, 96% | — | Urosepsis after decompression: 18.7% overall; risk ↑ with pyonephrosis/higher PCT | Definitive treatment differed between arms (p < 0.001) |

| Mokhmalji 2001 [23] | PCN success, 100% vs. stent, 80% | Major complications, 0%; PCN vs. 11% stent | — | — |

| Xu 2021 [24] | PCN vs. stent for urosepsis; similar clinical efficacy | Stent failure was more likely with proximal/UPJ obstruction (per abstract) | — | No significant differences in fever/WBC normalization or LOS |

| Goldsmith 2013 [25] | Both methods used; overall failure, 2.3% (3/130) | APACHE II was higher with PCN (15 vs. 11); stone size was larger with PCN (10 vs. 7 mm) | — | PCN → more ICU and longer LOS even after adjustment |

| Faw 2019 [26] | All patients stented | — | Urine culture: +58.3% | Stent ≤ 6–10 h from ED arrival reduced LOS (see Table 2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benea, A.; Porav-Hodade, D.; Turaiche, M.; Rosca, O.; Lighezan, D.-F.; Rachieru, C.; Stanga, L.; Ilie, A.C.; Sarau, O.S.; Sarau, C.A. Time to Decompression in Obstructive Urosepsis from Ureteral Calculi: Thresholds, Initial Diversion, and Early Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238546

Benea A, Porav-Hodade D, Turaiche M, Rosca O, Lighezan D-F, Rachieru C, Stanga L, Ilie AC, Sarau OS, Sarau CA. Time to Decompression in Obstructive Urosepsis from Ureteral Calculi: Thresholds, Initial Diversion, and Early Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238546

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenea, Adela, Daniel Porav-Hodade, Mirela Turaiche, Ovidiu Rosca, Daniel-Florin Lighezan, Ciprian Rachieru, Livia Stanga, Adrian Cosmin Ilie, Oana Silvana Sarau, and Cristian Andrei Sarau. 2025. "Time to Decompression in Obstructive Urosepsis from Ureteral Calculi: Thresholds, Initial Diversion, and Early Biomarkers: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238546

APA StyleBenea, A., Porav-Hodade, D., Turaiche, M., Rosca, O., Lighezan, D.-F., Rachieru, C., Stanga, L., Ilie, A. C., Sarau, O. S., & Sarau, C. A. (2025). Time to Decompression in Obstructive Urosepsis from Ureteral Calculi: Thresholds, Initial Diversion, and Early Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238546