Exacerbations and Lung Function in Polish Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treated with ICS/LABA: 2-Year Prospective, Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

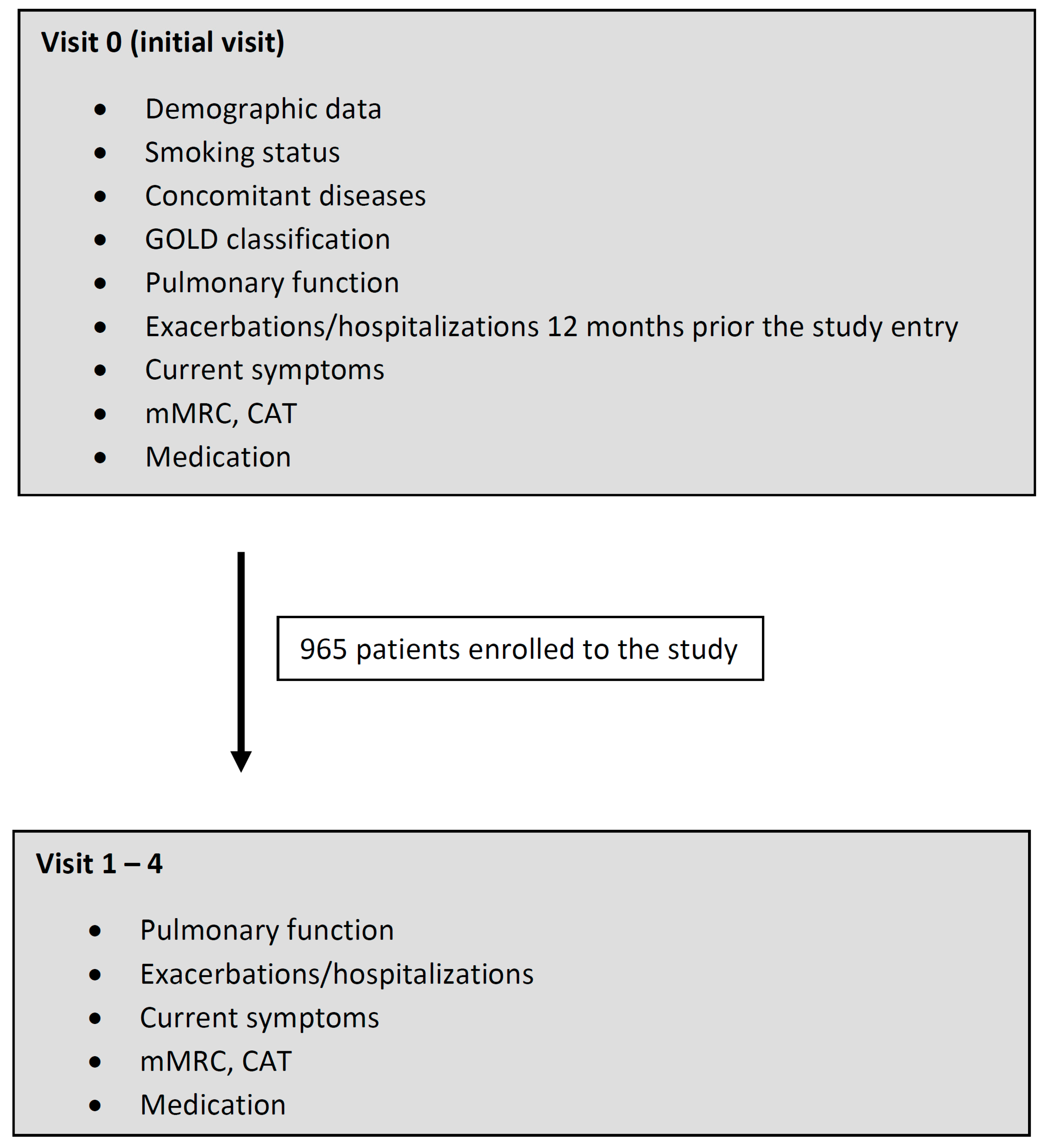

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Endpoints and Measurements of the Study

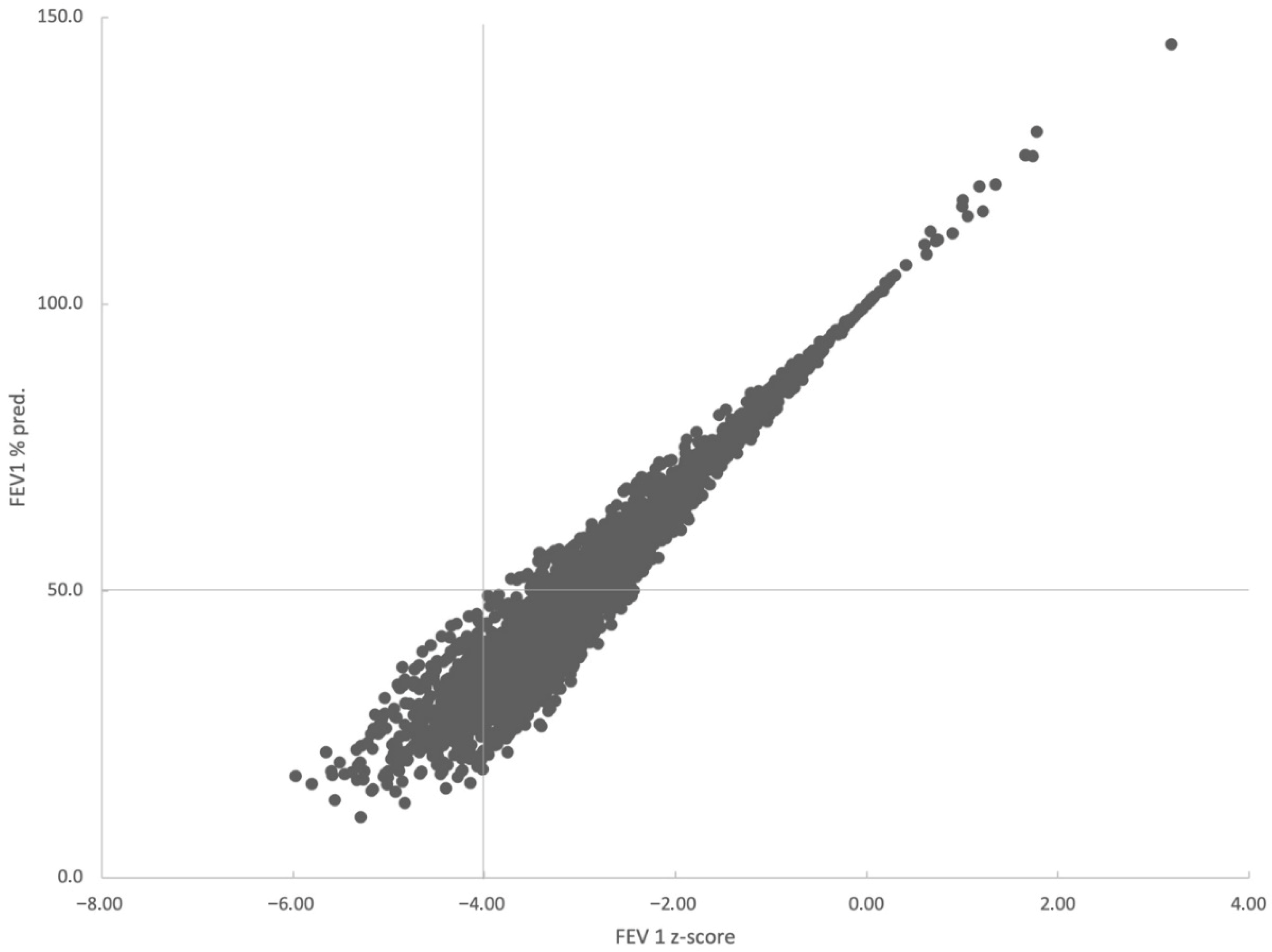

- non-severe; ATS/ERS-non-severe (FEV1 > 50% pred. and z-score > −4);

- GOLD-non-severe: ATS/ERS-severe (FEV1 > 50% pred. and z-score < −4);

- GOLD-severe—ATS/ERS-non-severe (FEV1 < 50% pred. and z-score > −4);

- GOLD-severe: ATS/ERS-severe (FEV1 < 50% pred. and z-score < −4).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics and Progress of the Study

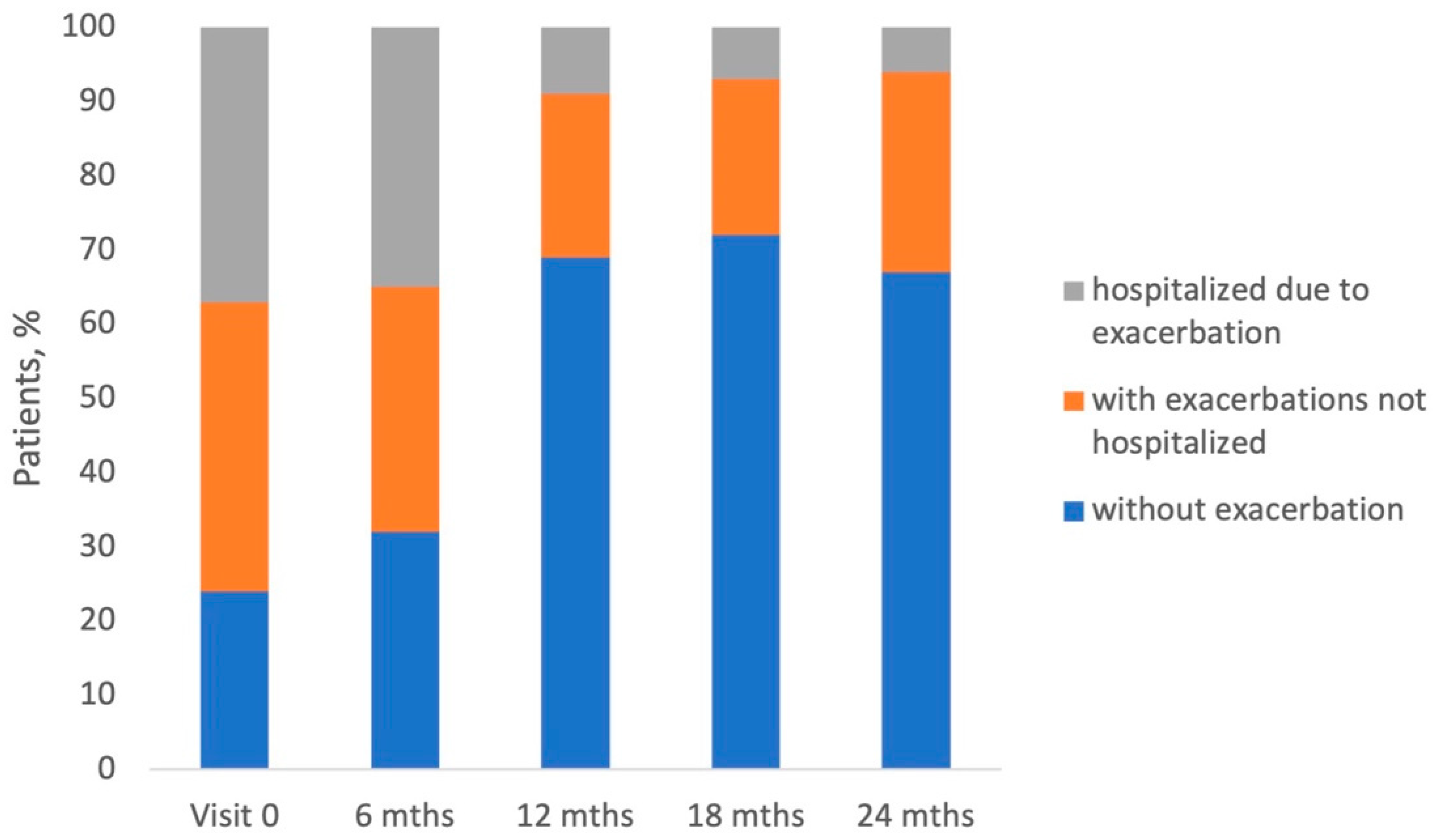

3.2. Exacerbations During the Study

3.3. Pulmonary Function

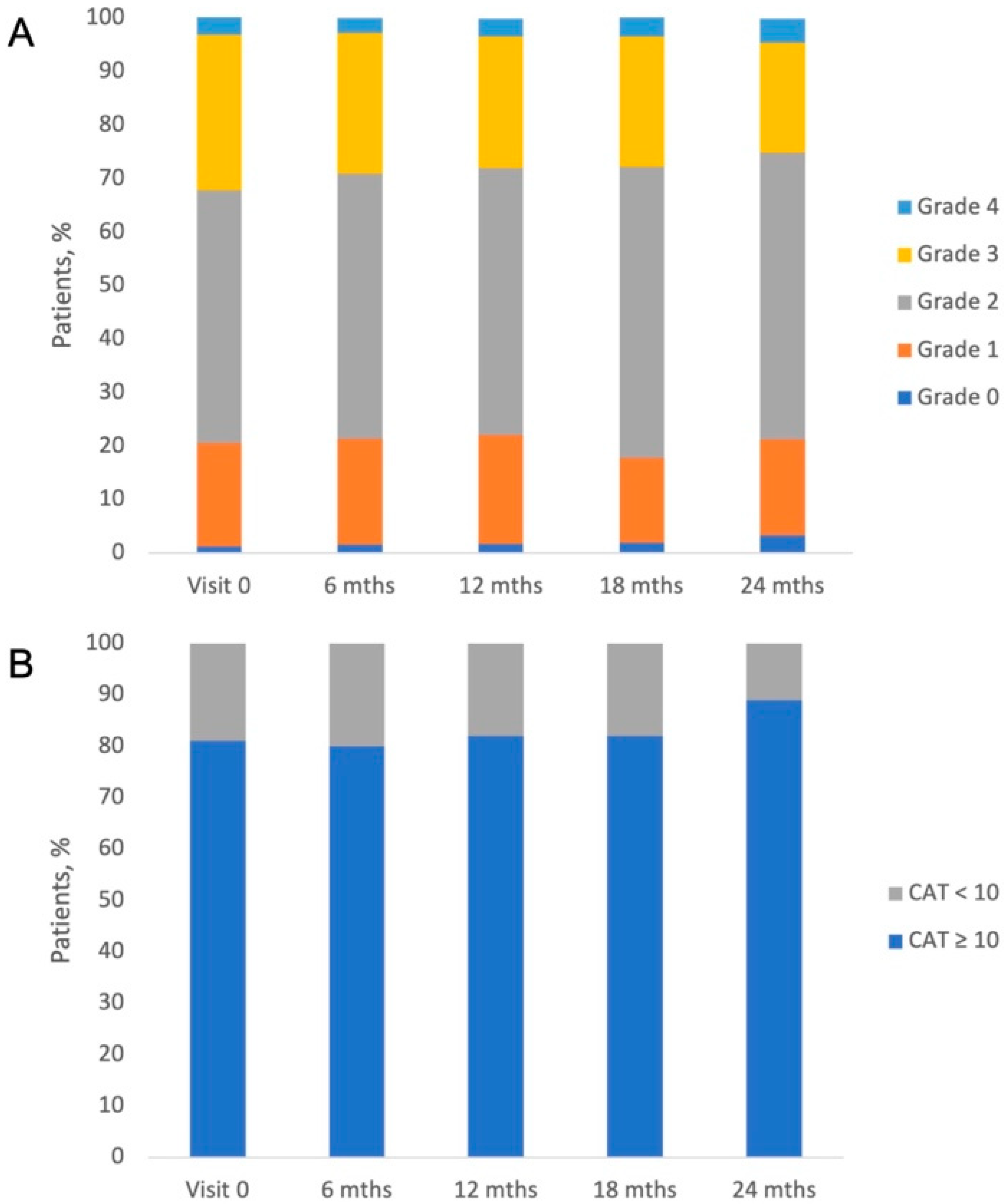

3.4. COPD Symptoms, Severity of Dyspnea, and GOLD Classification of the Study Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Decramer, M.; Janssens, W.; Miravitlles, M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2012, 379, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, J.; Kiley, J.; Bateman, E.D.; Viegi, G.; Cruz, A.A.; Khaltaev, N.; Ait Khaled, N.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Barreto, M.L.; Billo, N.; et al. Prioritised research agenda for prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.R.; Wedzicha, J.A. Update on Clinical Aspects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yawn, B.P.; Mintz, M.L.; Doherty, D.E. GOLD in Practice: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treatment and Management in the Primary Care Setting. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, C.; Marks, G.; Buist, S.; Gnatiuc, L.; Gislason, T.; McBurnie, M.A.; Nielsen, R.; Studnicka, M.; Toelle, B.; Benediktsdottir, B.; et al. The impact of COPD on health status: Findings from the BOLD study. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 42, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, F.; Cesana, G.; Conti, S.; Chiodini, V.; Aliberti, S.; Fornari, C.; Mantovani, L.G. The Clinical and Economic Impact of Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Cohort of Hospitalized Patients. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, G.T.; Tashkin, D.P.; Skärby, T.; Jorup, C.; Sandin, K.; Greenwood, M.; Pemberton, K.; Trudo, F. Effect of budesonide/formoterol pressurized metered-dose inhaler on exacerbations versus formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The 6-month, randomized RISE (Revealing the Impact of Symbicort in reducing Exacerbations in COPD) study. Respir. Med. 2017, 132, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calverley, P.M.; Anderson, J.A.; Celli, B.; Ferguson, G.T.; Jenkins, C.; Jones, P.W.; Yates, J.C.; Vestbo, J. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-P.; Yang, L.; Wu, Y.M.; Chen, P.; Wen, Z.G.; Huang, W.-J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, C.-Z.; Huang, S.-G.; Sun, T.; et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Combination Salmeterol (50 μg)/Fluticasone Propionate (500 μg) Inhalation Twice Daily Via Accuhaler in Chinese Patients With COPD. Chest 2007, 132, 1756–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.R.; Jones, P.W.; Calverley, P.M.A.; Celli, B.; Anderson, J.A.; Ferguson, G.T.; Yates, J.C.; Willits, L.R.; Vestbo, J. Efficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH study. Respir. Res. 2009, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Singh, D.; Vestbo, J.; Paggiaro, P.L.; Jones, P.W.; Bonnet-Gonod, F.; Cohuet, G.; Corradi, M.; Vezzoli, S.; Petruzzelli, S.; et al. Extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in severe COPD patients with history of exacerbations. Respir. Med. 2014, 108, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, S.W.Y.; Haughney, J.; Ryan, D.; Small, I.; Lavorini, F.; Papi, A.; Singh, D.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Hurst, J.R.; Patel, S.; et al. A Comparison of the Real-Life Clinical Effectiveness of the Leading Licensed ICS/LABA Combination Inhalers in the Treatment for COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 3093–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: The global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusselle, G.; Price, D.; Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Miravitlles, M.; Keininger, D.L.; Stewart, R.; Baldwin, M.; Jones, R.C. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: An analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int. J. Chron. Obstr. Pulmon. Dis. 2015, 10, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sator, L.; Horner, A.; Studnicka, M.; Lamprecht, B.; Kaiser, B.; McBurnie, M.A.; Buist, A.S.; Gnatiuc, L.; Mannino, D.M.; Janson, C.; et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in Subjects With Unobstructed Spirometry: A BOLD Analysis. Chest 2019, 156, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P. Spirometric screening for COPD: Wishful thinking, not evidence. Thorax 2007, 62, 742–743. [Google Scholar]

- Valipour, A.; Avdeev, S.; Barczyk, A.; Bayer, V.; Fridlender, Z.; Georgieva, M.; Kudela, O.; Medvedchikov, A.; Miron, R.; Sanzharovskaya, M.; et al. Therapeutic Success of Tiotropium/Olodaterol, Measured Using the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ), in Routine Clinical Practice: A Multinational Non-Interventional Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, A.; Tamm, M.; Kociánová, J.; Bayer, V.; Sanzharovskaya, M.; Medvedchikov, A.; Haaksma-Herczegh, M.; Mucsi, J.; Fridlender, Z.; Toma, C.; et al. Improvement In Self-Reported Physical Functioning With Tiotropium/Olodaterol In Central And Eastern European COPD Patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2019, 14, 2343–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, R.; Criée, C.-P.; Kardos, P.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Kostikas, K.; Lossi, N.S.; Worth, H. Dual bronchodilation vs triple therapy in the “real-life” COPD DACCORD study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 2557–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantucci, C.; Modina, D. Lung function decline in COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2012, 7, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.; Nikolaev, I.; Nemeth, I. Real-life evaluation of COPD treatment in a Bulgarian population: A 1-year prospective, observational, noninterventional study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblizek, V.; Milenkovic, B.; Barczyk, A.; Tkacova, R.; Somfay, A.; Zykov, K.; Tudoric, N.; Kostov, K.; Zbozinkova, Z.; Svancara, J.; et al. Phenotypes of COPD patients with a smoking history in Central and Eastern Europe: The POPE Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, H.; Buhl, R.; Criée, C.-P.; Kardos, P.; Mailänder, C.; Vogelmeier, C. The ‘real-life’ COPD patient in Germany: The DACCORD study. Respir. Med. 2016, 111, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, T.; Friedrich, F.W.; Beier, J. Effectiveness and Tolerability of LABA/LAMA Fixed-Dose Combinations Aclidinium/Formoterol, Glycopyrronium/Indacaterol and Umeclidinium/Vilanterol in the Treatment of COPD in Daily Practice—Results of the Non-Interventional DETECT Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntritsos, G.; Franek, J.; Belbasis, L.; Christou, M.A.; Markozannes, G.; Altman, P.; Fogel, R.; Sayre, T.; Ntzani, E.E.; Evangelou, E. Gender-specific estimates of COPD prevalence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.D. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Current burden and future projections. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 27, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, A.; Dickens, C.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Afzal, C.W.; Tomenson, B.; Coventry, P.A.; Guthrie, E. Depression predicts emergency care use in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A large cohort study in primary care. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2019, 14, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikjord, S.A.A.; Brumpton, B.M.; Mai, X.-M.; Romundstad, S.; Langhammer, A.; Vanfleteren, L. The HUNT study: Association of comorbidity clusters with long-term survival and incidence of exacerbation in a population-based Norwegian COPD cohort. Respirology 2022, 27, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.W.B.; Ho, R.C.M.; Cheung, M.W.L.; Fu, E.; Mak, A. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solidoro, P.; Patrucco, F.; Bagnasco, D. Comparing a fixed combination of budesonide/formoterol with other inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting beta-agonist combinations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A review. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2019, 13, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K.; Janson, C.; Lisspers, K.; Jørgensen, L.; Stratelis, G.; Telg, G.; Ställberg, B.; Johansson, G. Combination of budesonide/formoterol more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The PATHOS study. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, M.R.; Schuermann, W.; Beckman, O.; Persson, T.; Polanowski, T. Effect on lung function and morning activities of budesonide/formoterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in patients with COPD. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2009, 3, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Mapel, D.; Petersen, H.; Blanchette, C.; Ramachandran, S. Comparative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol for COPD management. J. Med. Econ. 2011, 14, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D.M.; Davis, J.; Williams, S.A.; Tunceli, O.; Wu, B.; Hollis, S.; Strange, C.; Trudo, F. Comparative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol combination and fluticasone/salmeterol combination among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients new to controller treatment: A US administrative claims database study. Respir. Res. 2015, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, V.; Sangiorgi, D.; Buda, S.; Degli Esposti, L. Comparative analysis of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol combinations in COPD patients: Findings from a real-world analysis in an Italian setting. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2016, 11, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashkin, D.P.; Amin, A.N.; Kerwin, E.M. Comparing Randomized Controlled Trials and Real-World Studies in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Pharmacotherapy. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 1225–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n = 965 |

|---|---|

| Age [years] | |

| Mean (SD) | 66.9 (9.4) |

| Missing | 4 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 311 (32.2) |

| Male | 651 (67.5) |

| Missing | 3 (0.3) |

| BMI [kg/m2] | |

| Mean (SD) | 27.1 (5.4) |

| Missing | 6 |

| Smoker, n (%) | |

| Smoker | 345 (35.8) |

| Ex-Smoker | 533 (55.2) |

| Non-smoker | 80 (8.3) |

| Missing | 7 (0.7) |

| Concomitant diseases; n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 568 (70.7) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 249 (31) |

| Heart failure | 165 (20.5) |

| Diabetes | 154 (19.2) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 153 (19.1) |

| Osteoporosis | 60 (7.5) |

| Depression and anxiety disorder | 55 (6.8) |

| Myopathy (muscle weakness) | 45 (5.6) |

| Persistent atrial fibrillation | 36 (4.5) |

| Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 33 (4.1) |

| Lung cancer | 7 (0.9) |

| Other cancers | 29 (3.6) |

| Sleep apneas | 15 (1.9) |

| Other disorders | 310 (32.1) |

| Parameter | Visit 0 | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-acting beta2-adrenergic agonists | 416 (43.1%) | 328 (37.8%) | 275 (38.9%) | 214 (39.9%) | 70 (46.4%) |

| LABAs | 69 (7.2%) | 54 (6.2%) | 47 (6.6%) | 40 (7.5%) | 8 (5.3%) |

| Short-acting anticholinergics | 256 (26.5%) | 199 (23%) | 161 (22.8%) | 122 (22.8%) | 45 (29.8%) |

| LAMAs | 600 (62.2%) | 511 (58.9%) | 481 (68%) | 373 (69.6%) | 104 (68.9%) |

| ICS | 26 (2.7%) | 23 (2.7%) | 26 (3.7%) | 24 (4.5%) | 3 (2%) |

| ICS/LABA | 926 (96%) | 813 (93.8%) | 704 (99.6%) | 525 (97.9%) | 147 (97.4%) |

| Beclomethasone/formoterol | 364 (37.7%) | 320 (36.9%) | 276 (39%) | 198 (36.9%) | 53 (35.1%) |

| Budesonide/formoterol | 208 (21.6%) | 179 (20.6%) | 154 (21.8%) | 119 (22.2%) | 24 (15.9%) |

| Fluticasone/salmeterol | 354 (36.7%) | 314 (36.2%) | 274 (38.8%) | 208 (38.8%) | 70 (46.4%) |

| PD4 inhibitors | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Aminophylline | 369 (38.2%) | 308 (35.5%) | 274 (38.8%) | 217 (40.5%) | 69 (45.7%) |

| Other drugs | 25 (2.6%) | 29 (3.0%) | 36 (3.7%) | 38 (3.9%) | 11 (1.1%) |

| Variable | Coefficient | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | −0.2682 | 0.7648 | 0.5631 to 1.0387 | 0.086 |

| Age (years) | −0.00057465 | 0.9994 | 0.9820 to 1.0172 | 0.9491 |

| BMI kg/m2 | −0.017148 | 0.9830 | 0.9571 to 1.0096 | 0.2083 |

| Comorbidities | 0.44212 | 1.5560 | 1.0989 to 2.2033 | 0.0127 |

| GOLD-severe—ATS/ERS non-severe * | −0.014633 | 0.9855 | 0.7152 to 1.3580 | 0.9287 |

| GOLD-severe—ATS/ERS-severe * | −0.020001 | 0.9802 | 0.6148 to 1.5627 | 0.933 |

| ‘Decliner’ | −0.069795 | 0.9326 | 0.6924 to 1.2561 | 0.646 |

| mMRC | 0.97698 | 2.6564 | 2.1632 to 3.2621 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | −0.27197 | 0.7619 | 0.5575 to 1.0411 | 0.0878 |

| Airflow Limitation, n (%) | Visit 0 | 6 Months | 12 Months | 18 Months | 24 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (>80%) | 20 (2.5) | 28 (4.6) | 20 (3.7) | 15 (4.0) | 3 (2.6) |

| Moderate (50–80%) | 198 (25.1) | 173 (28.5) | 155 (28.9) | 117 (31.0) | 30 (25.9) |

| Severe (30–50%) | 466 (59.0) | 321 (52.9) | 293 (54.7) | 194 (51.5) | 66 (56.9) |

| Very severe (<30%) | 106 (13.4) | 85 (14.0) | 68 (12.7) | 51 (13.5) | 17 (14.7) |

| Characteristic | Decliners, n = 330 | Non-Decliners, n = 592 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n (%) | 244 (73.9) | 382 (64.5) | 0.004 a | |

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 66 (60–72) | 67 (61–75) | 0.026 b | |

| FEV1% pred. median (IQR) | 46.62 (38.66–59.22) | 42.06 (33.76–53.6) | <0.001 b | |

| FEV1 (z-score) (mean, SD) | −2.96 (1.04) | −3.21 (1) | <0.001 c | |

| FVC % pred. median (IQR) | 68.66 (57.41–80.66) | 62.92 (52.07–75.3) | <0.001 b | |

| FVC (z-score) mean (SD) | −1.99 (1.17) | −2.29 (1.23) | <0.001 c | |

| GOLD-non-severe/ATS/ERS-non-severe, n (%) | 139 (42.1) | 176 (29.7) | 0.004 a | |

| GOLD-severe/ATS/ERS-non-severe, n (%) | 155 (47.0) | 300 (50.7) | ||

| GOLD-severe/ATS/ERS-severe, n (%) | 36 (10.9) | 116 (19.6) | ||

| CAT, median (IQR) | 17 (12–22) | 17 (11–23) | 0.549 b | |

| mMRC grade, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 9 (1.5) | 0.004 a |

| 1 | 72 (21.8) | 105 (17.9) | ||

| 2 | 176 (53.3) | 256 (43.6) | ||

| 3 | 74 (22.4) | 194 (33.0) | ||

| 4 | 7 (2.1) | 23 (3.9) | ||

| Exacerbations, n (%) | yes | 285 (88.2) | 507 (88.6) | 0.943 a |

| no | 38 (11.8) | 65 (11.4) | ||

| Ever-smokers, n (%) | yes | 308 (93.9) | 534 (90.5) | 0.096 a |

| no | 20 (6.1) | 56 (9.5) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | yes | 125 (37.9) | 234 (39.5) | 0.673 a |

| no | 205 (62.1) | 358 (60.5) |

| Characteristic | GOLD-Non-Severe/ ATS/ERS-Non-Severe | GOLD-Severe/ ATS/ERS-Non-Severe | GOLD-Severe/ATS/ERS-Severe | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n (%) | 190 (60.3) | 325 (71.4) | 111 (73.0) | 0.002 a | |

| Age [years], median (IQR) | 67 (60–75) | 69 (64–75) | 60 (55–64) | <0.001 b | |

| FEV1% pred., median (IQR) | 62.68 (55.69–73.6) | 40.78 (36.51–45.06) | 28.73 (25.26–33.98) | <0.001 b | |

| FEV1 (z-score), mean (SD) | −2.06 (0.88) | −3.43 (0.34) | −4.41 (0.38) | <0.001 c | |

| FVC % pred., median (IQR) | 78.16 (67.88–90.72) | 60.82 (52.44–71.44) | 50.94 (42.93–60.41) | <0.001 b | |

| FVC (z-score), mean (SD) | −1.32 (1.03) | −2.39 (0.99) | −3.36 (0.87) | <0.001 c | |

| Decliners, n (%) | 139 (44.1) | 155 (34.1) | 36 (23.7) | <0.001 a | |

| Non-decliners, n (%) | 176 (55.9) | 300 (65.9) | 116 (76.3) | ||

| mMRC grade, n (%) | 0 | 8 (2.6) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | <0.001 a |

| 1 | 85 (27.2) | 68 (15.0) | 24 (15.8) | ||

| 2 | 156 (50.0) | 214 (47.2) | 62 (40.8) | ||

| 3 | 60 (19.2) | 154 (34.0) | 54 (35.5) | ||

| 4 | 3 (1.0) | 15 (3.3) | 12 (7.9) | ||

| CAT, median (IQR) | 16 (10.25–22) | 16 (11–22) | 19 (12–24.5) | 0.006 b | |

| Exacerbations, n (%) | yes | 267 (88.4) | 394 (88.9) | 131 (87.3) | 0.866 a |

| no | 35 (11.6) | 49 (11.1) | 19 (12.7) | ||

| Ever-smokers, n (%) | yes | 280 (89.5) | 417 (91.9) | 145 (96.0) | 0.055 a |

| no | 33 (10.5) | 37 (8.1) | 6 (4.0) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | yes | 114 (36.2) | 201 (44.2) | 44 (28.9) | 0.002 a |

| no | 201 (63.8) | 254 (55.8) | 108 (71.1) |

| GOLD 2017–2022 Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mMRC | A | B | C | D | |

| 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 (1.1%) |

| 1 | 58 | 75 | 15 | 29 | 177 (19.3%) |

| 2 | 0 | 219 | 0 | 213 | 432 (47.1%) |

| 3 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 188 | 268 (29.2%) |

| 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 27 | 30 (3.3%) |

| 67 (7.3%) | 378 (41.2%) | 15 (1.6%) | 457 (49.8%) | 917 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boros, P.W.; Pawliczak, R.; Dębowski, T. Exacerbations and Lung Function in Polish Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treated with ICS/LABA: 2-Year Prospective, Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8544. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238544

Boros PW, Pawliczak R, Dębowski T. Exacerbations and Lung Function in Polish Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treated with ICS/LABA: 2-Year Prospective, Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8544. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238544

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoros, Piotr W., Rafał Pawliczak, and Tomasz Dębowski. 2025. "Exacerbations and Lung Function in Polish Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treated with ICS/LABA: 2-Year Prospective, Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8544. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238544

APA StyleBoros, P. W., Pawliczak, R., & Dębowski, T. (2025). Exacerbations and Lung Function in Polish Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treated with ICS/LABA: 2-Year Prospective, Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8544. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238544