Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Acetazolamide in Stable COPD Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

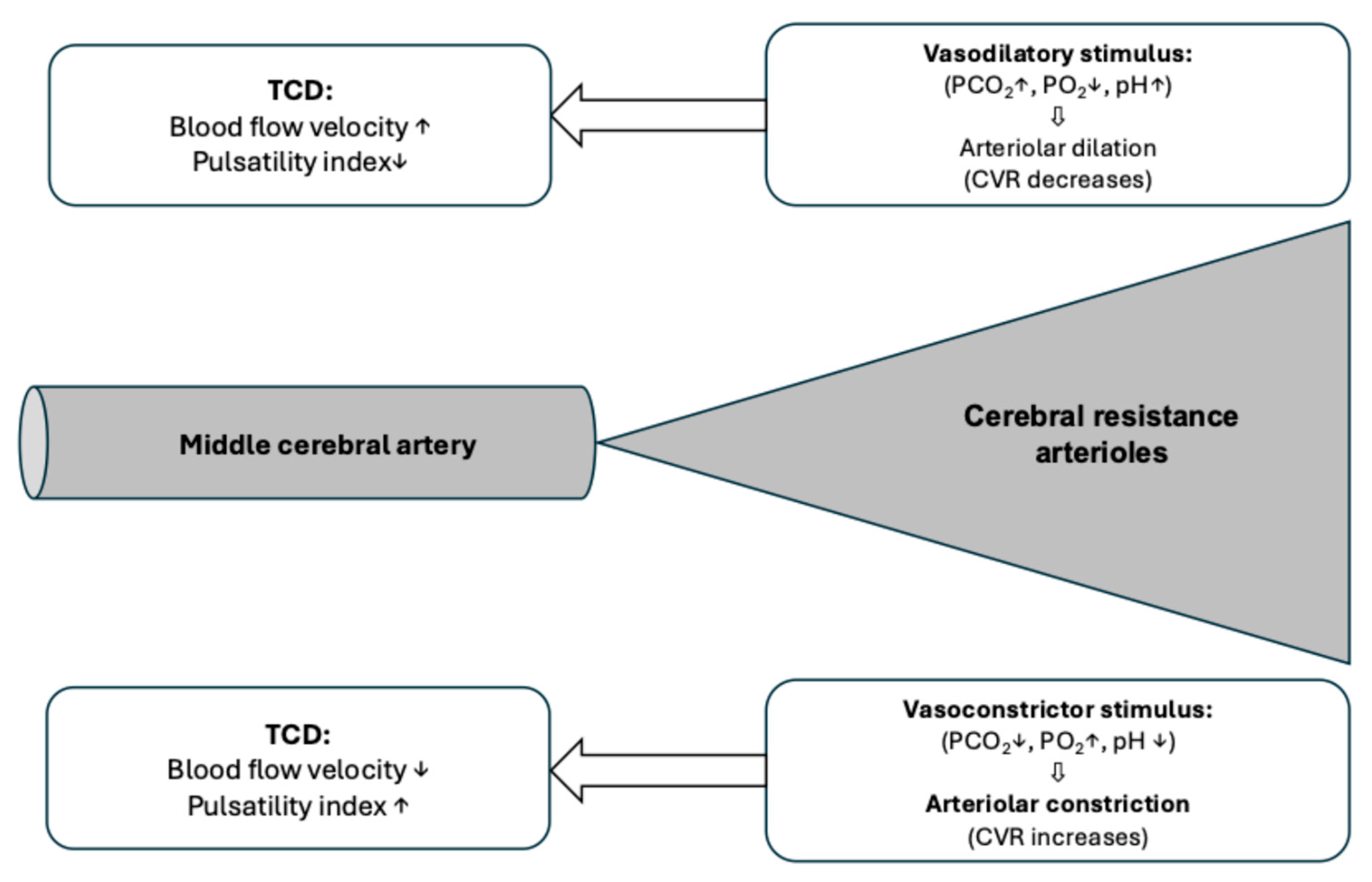

Calculation of Cerebrovascular Reactivity and Reserve Capacity

3. Results

3.1. Results of Blood Gas Analysis Measurements

3.2. Results of Cerebral Blood Flow Velocity Measurements

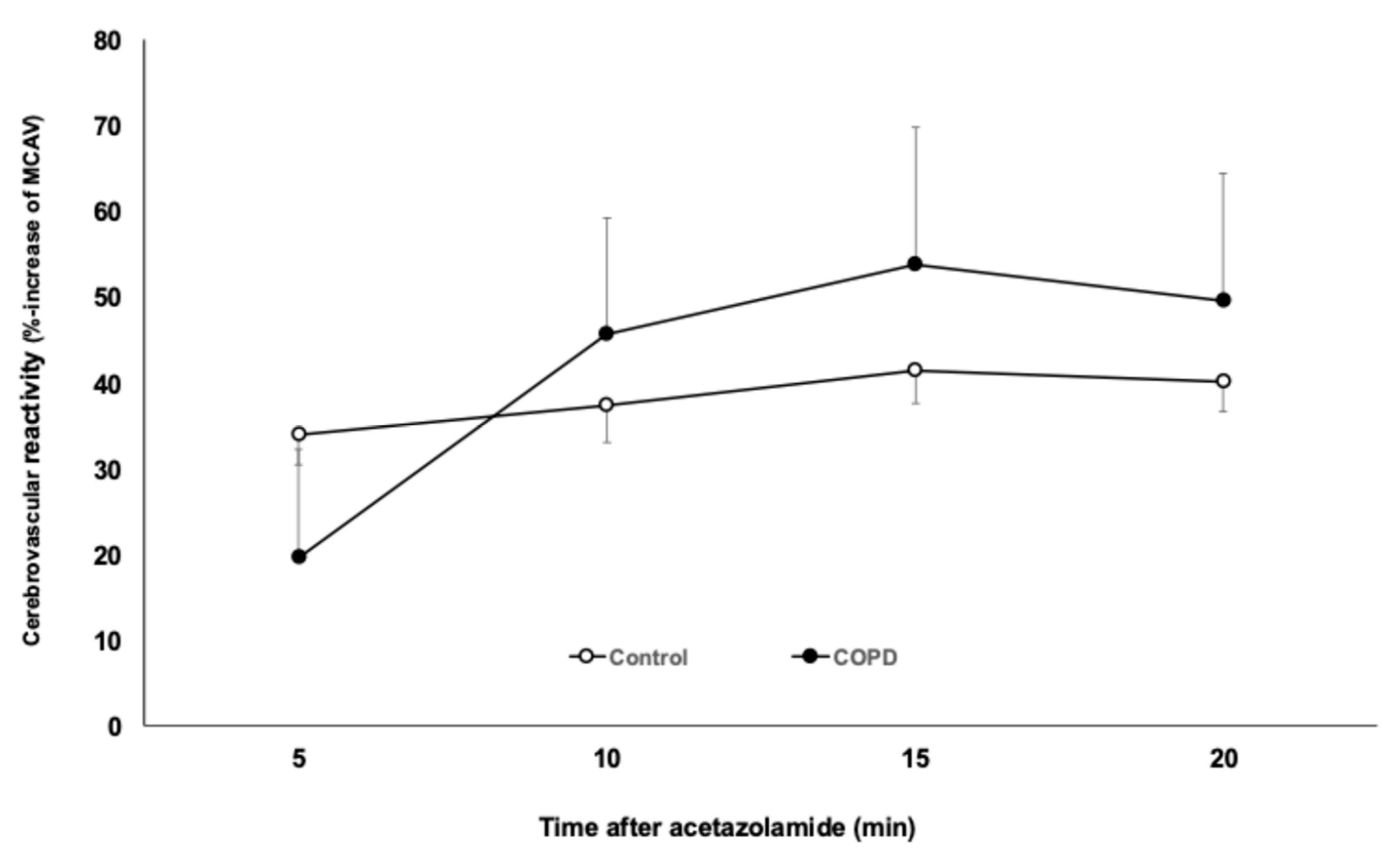

3.3. Cerebrovascular Reactivity (CVR) Measurements

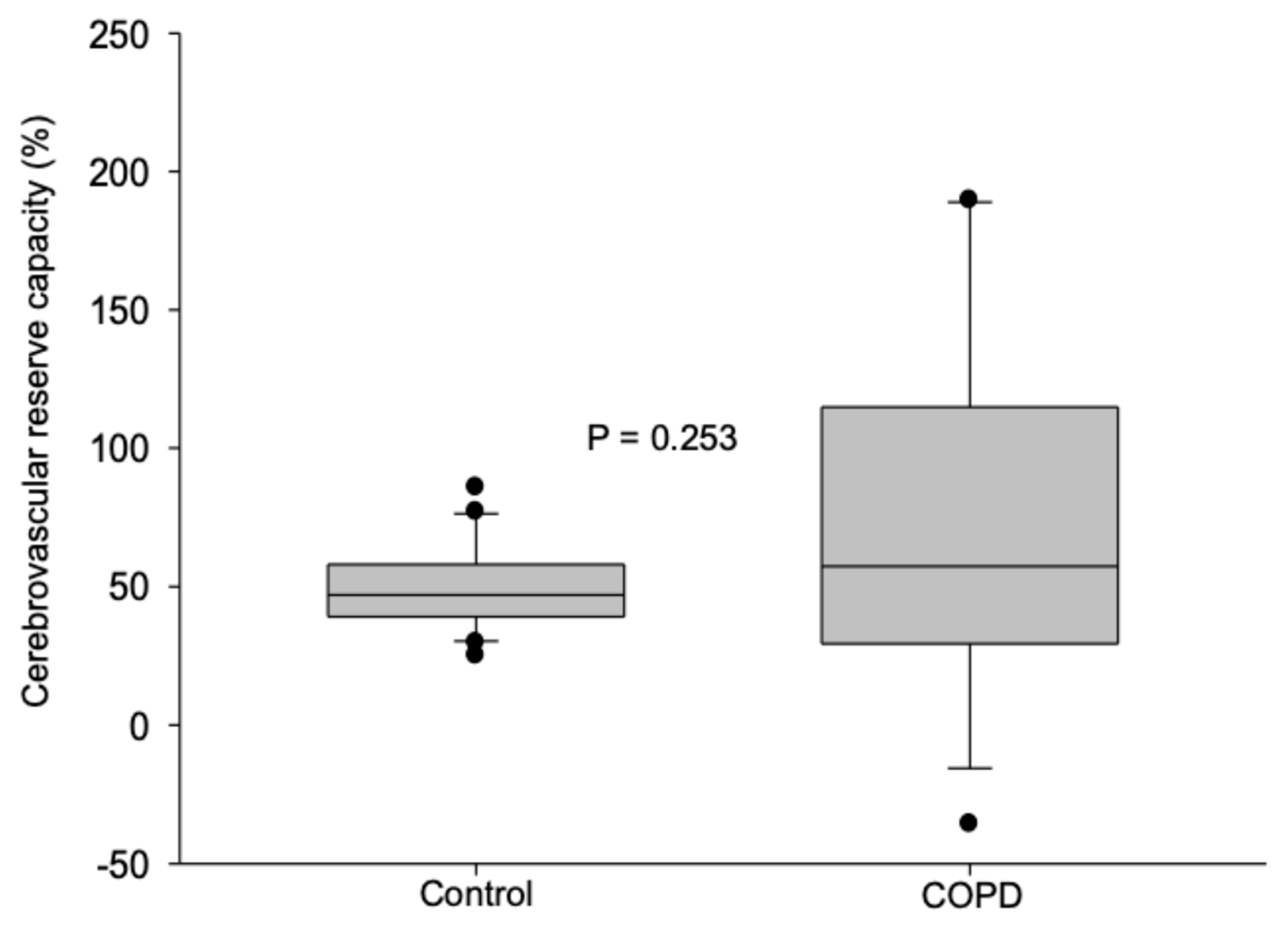

3.4. Cerebrovascular Reserve Capacity

Relationship Between Cerebrovascular Reserve Capacity and Confounding Factors

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlateanu, A.; Covantev, S.; Mathioudakis, A.G.; Botnaru, V.; Siafakas, N. Prevalence and burden of comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respir. Investig. 2016, 54, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portegies, M.L.; Lahousse, L.; Joos, G.F.; Hofman, A.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Stricker, B.H.; Brusselle, G.G.; Ikram, M.A. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and the Risk of Stroke. The Rotterdam Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feary, J.R.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Smith, C.J.; Hubbard, R.B.; Gibson, J.E. Prevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: A comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax 2010, 65, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, P.S.; Anstey, K.J.; Parslow, R.A.; Wen, W.; Maller, J.; Kumar, R.; Christensen, H.; Jorm, A.F. Pulmonary function, cognitive impairment and brain atrophy in a middle-aged community sample. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2006, 21, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spilling, C.A.; Jones, P.W.; Dodd, J.W.; Barrick, T.R. White matter lesions characterise brain involvement in moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but cerebral atrophy does not. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, J.W.; Chung, A.W.; van den Broek, M.D.; Barrick, T.R.; Charlton, R.A.; Jones, P.W. Brain structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A multimodal cranial magnetic resonance imaging study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, H.S.; Joutel, A. The pathogenesis of cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive impairment. Physiol. Rev. 2025, 105, 1075–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regenhardt, R.W.; Nolan, N.M.; Das, A.S.; Mahajan, R.; Monk, A.D.; LaRose, S.L.; Migdady, I.; Chen, Y.; Sheriff, F.; Bai, X.; et al. Transcranial Doppler cerebrovascular reactivity: Thresholds for clinical significance in cerebrovascular disease. J. Neuroimaging 2024, 34, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülesdi, B.; Limburg, M.; Bereczki, D.; Michels, R.P.; Neuwirth, G.; Legemate, D.; Valikovics, A.; Csiba, L. Impairment of cerebrovascular reactivity in long-term type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 1997, 46, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, K.; Petras, S.; Ducasse, V.; Chokron, S.; Helft, G.; Blacher, J.; Caillat-Vigneron, N. Brain perfusion SPECT imaging and acetazolamide challenge in vascular cognitive impairment. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2012, 33, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Agusti, A.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P.J.; Bourbeau, J.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Frith, P.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.; et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: The GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1900164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oláh, L.; Valikovics, A.; Bereczki, D.; Fülesdi, B.; Munkácsy, C.; Csiba, L. Gender-related differences in acetazolamide-induced cerebral vasodilatory response: A transcranial Doppler study. J. Neuroimaging 2000, 10, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settakis, G.; Molnár, C.; Kerényi, L.; Kollár, J.; Legemate, D.; Csiba, L.; Fülesdi, B. Acetazolamide as a vasodilatory stimulus in cerebrovascular diseases and in conditions affecting the cerebral vasculature. Eur. J. Neurol. 2003, 10, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clivati, A.; Ciofetti, M.; Cavestri, R.; Longhini, E. Cerebral vascular responsiveness in chronic hypercapnia. Chest 1992, 102, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatmári, S.; Végh, T.; Csomós, A.; Hallay, J.; Takács, I.; Molnár, C.; Fülesdi, B. Impaired cerebrovascular reactivity in sepsis-associated encephalopathy studied by acetazolamide test. Crit. Care. 2010, 14, R50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukralla, A.A.; Dolan, E.; Delanty, N. Acetazolamide: Old drug, new evidence? Epilepsia Open 2022, 7, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, W.M.; Koeberle, B. The dose-response relationship of acetazolamide on the cerebral blood flow in normal subjects. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2000, 10, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavati, M.; Buljan, K.; Tomić, S.; Horvat, M.; Butković-Soldo, S. Impaired cerebrovascular reactivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2019, 119, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, D.I.; de-Lima-Oliveira, M.; Nogueira, R.C.; Carvalho-Pinto, R.M.; Bor-Seng-Shu, E.; Panerai, R.B.; Carvalho, C.R.F.; Salinet, A.S. Integrative assessment of cerebral blood regulation in COPD patients. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2024, 319, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, S.; Kaya, I.; Cece, H.; Gencer, M.; Ziylan, Z.; Yalcin, F.; Turksoy, O. Impact of COPD exacerbation on cerebral blood flow. Clin. Imaging 2012, 36, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Ven, M.J.; Colier, W.N.; Van der Sluijs, M.C.; Kersten, B.T.; Oeseburg, B.; Folgering, H. Ventilatory and cerebrovascular responses in normocapnic and hypercapnic COPD patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 18, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Female/Male | 8/9 |

| Age (years) | 60.8 ± 4.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.9 ± 5.6 |

| Mini Mental Score | 26.8 ± 3.1 |

| FVC (L) | 2.45 ± 0.97 |

| FVC% | 72.8 ± 19.1 |

| FEV1 (L) | 1.35 ± 0.74 |

| FEV1% | 48.2 ± 16.0 |

| FEV1/FVC | 52.6 ± 10.1 |

| FEF25-75 (L/s) | 0.85 ± 6.63 |

| FEF 25-75% | 27.2 ± 16.8 |

| Rest | 5 min After ACZ | 10 min After ACZ | 15 min After ACZ | 20 min After ACZ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.43 ± 0.04 | 7.41 ± 0.04 | 7.41 ± 0.04 | 7.41 ± 0.04 | 7.41 ± 0.05 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 42.5 ± 6.8 | 45.5 ± 7.6 | 45.2 ± 7.6 | 45.6 ± 7.6 | 45.0 ± 8.1 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 74.7 ± 16.9 | 81.5 ± 18.7 | 87.5 ± 22.4 | 87.6 ± 20.6 | 87.3 ± 20.0 |

| HCO3 (mmol/L) | 27.6 ± 2.6 | 27.6 ± 2.4 | 27.5 ± 2.4 | 27.6 ± 2.5 | 27.4 ± 2.4 |

| Control (n = 20) | COPD (n = 17) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | |||

| Systolic | 85.9 ± 13.8 | 72.0 ± 24.8 | p = 0.04 |

| Diastolic | 45.6 ± 8.8 | 28.5 ± 9.7 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Mean | 58.2 ± 12.0 | 44.2 ± 16.0 | p < 0.01 |

| PI | 0.86 (0.64–1.0) | 0.99 (0.9–1.0) | p < 0.05 |

| 5 min after acetazolamide | |||

| Systolic | 116.0 (98–126) | 84.8 (64–109) | p < 0.01 |

| Diastolic | 61.9 ± 12.7 | 37.2 ± 15 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Mean | 77.8 ± 17.1 | 55.3 ± 22.8 | p < 0.01 |

| PI | 0.8 ± 0.16 | 0.89 ± 0.13 | p = 0.07 |

| 10 min after acetazolamide | |||

| Systolic | 119 (108–135) | 89 (63–115) | p < 0.05 |

| Diastolic | 65 (52–77) | 41 (29–52) | p < 0.01 |

| Mean | 79 (67–93) | 57.3 (41.6–75.8) | p < 0.05 |

| PI | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 0.83 ± 0.17 | p < 0.05 |

| 15 min after acetazolamide | |||

| Systolic | 126 (113–137) | 91.1 (66.1–126.9) | p < 0.01 |

| Diastolic | 66 (57–70) | 38.5 (28.1–53.5) | p < 0.01 |

| Mean | 82 (71–91) | 56.0 (42.5–81.8) | p = 0.01 |

| PI | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | p = 0.03 |

| 20 min afer acetazolamide | |||

| Systolic | 124 (116–132) | 86.6 (68.1–118.2) | p < 0.01 |

| Diastolic | 64.7 ± 14.6 | 64.7 ± 14.6 | p < 0.01 |

| Mean | 82 (69–93) | 55 (40.4–75.8) | p = 0.01 |

| PI | 0.742 ± 0.141 | 0.85 ± 0.14 | p < 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siró, P.; Szabó-Szűcs, R.; Dudás, V.; Horváth, I.; Fülesdi, B.; Vaskó, A. Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Acetazolamide in Stable COPD Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238535

Siró P, Szabó-Szűcs R, Dudás V, Horváth I, Fülesdi B, Vaskó A. Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Acetazolamide in Stable COPD Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238535

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiró, Péter, Regina Szabó-Szűcs, Viktória Dudás, Ildikó Horváth, Béla Fülesdi, and Attila Vaskó. 2025. "Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Acetazolamide in Stable COPD Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238535

APA StyleSiró, P., Szabó-Szűcs, R., Dudás, V., Horváth, I., Fülesdi, B., & Vaskó, A. (2025). Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Acetazolamide in Stable COPD Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238535