Association Between Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation Outcome and Largely Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pediatric Patients—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- Population: Pediatric patients with congenital GI malformations.

- Intervention: Concurrent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Comparison: None.

- Outcomes: Clinical outcomes (intra- and postoperative complications, surgical approach, and postoperative outcomes and mortality).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Synthesis

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

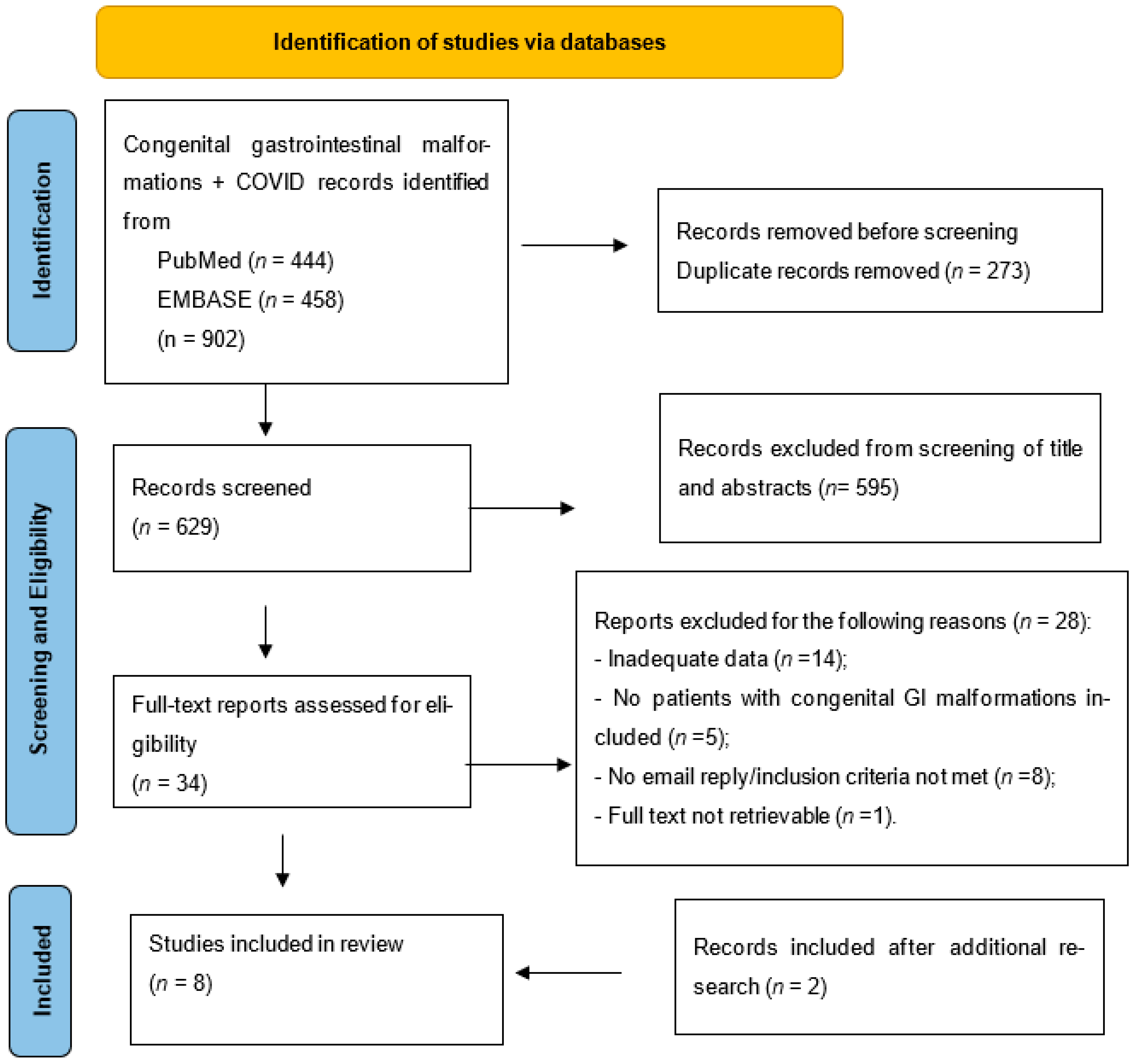

3.1. Study Retrieval Strategy

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Patients’ Characteristics

3.4. COVID-19 Characteristics

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARM | anorectal malformation |

| CHPS | congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 19 |

| DA | duodenal atresia |

| EA | esophageal atresia |

| EA-TEF | esophageal atresia–tracheoesophageal fistula |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| HD | Hirschsprung disease |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| NA | not applicable |

| Neg | negative |

| NICU | neonatal intensive care unit |

| PICOS | population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design |

| POD | postoperative day |

| Pos | positive |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| TEF | tracheoesophageal fistula |

References

- Ludwig, K.; De Bartolo, D.; Salerno, A.; Ingravallo, G.; Cazzato, G.; Giacometti, C.; Dall’igna, P. Congenital anomalies of the tubular gastrointestinal tract. Pathologica 2022, 114, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, L.M.; Wershil, B.K. Anatomy, histology, embryology, and developmental anomalies of the small and large intestine. In Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 10th ed.; Saunders, Elsevier Inc, 1649: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Newborn Mortality. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- GBD 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators (2016). Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1725–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commision. Prevalence Charts and Tables. Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/eurocat/eurocat-data/prevalence_en (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Kouame, B.; N′guetta-Brou, I.; Kouame, G.Y.; Sounkere, M.; Koffi, M.; Yaokreh, J.; Odehouri-Koudou, T.; Tembely, S.; Dieth, G.; Ouattara, O.; et al. Epidemiology of congenital abnormalities in West Africa: Results of a descriptive study in teaching hospitals in Abidjan: Cote d’Ivoire. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2015, 12, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, S.; Fall, M.; Mbaye, P.A.; Wese, S.F.; Lo, F.B.; Oumar, N. Congenital Malformations of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Neonates at Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital in Dakar. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2022, 19, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Pan, W.; Wu, W.; Zhu, D.; Wang, J. Study of Correlation between Fetal Bowel Dilation and Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation. Children 2024, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaos, G.; Misiakos, E.P. Congenital Anomalies of the Gastrointestinal Tract Diagnosed in Adulthood—Diagnosis and Management. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010, 14, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, C.; Borkar, N.B.; Singh, S.; Mane, S.; Sinha, C. Delayed presentation of duodenal atresia. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2023, 20, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global PaedSurg Research Collaboration. Mortality from gastrointestinal congenital anomalies at 264 hospitals in 74 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: A multicentre, international, prospective cohort study. Lancet 2021, 398, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.-C.; Søreide, K. Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel’s diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine 2018, 97, e12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.; Pakarinen, M.P.; Tam, P.; Laje, P.; Holcomb, G.W. From the editors: The COVID-19 crisis and its implications for pediatric surgeons. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazingi, D.; Ihediwa, G.; Ford, K.; O Ademuyiwa, A.; Lakhoo, K. Mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on children’s surgery in Africa. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2020, 5, e003016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, E.; Skerritt, C.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Hooker, E.; Lander, A.; Gee, O.; Jester, I. Children with congenital colorectal malformations during the UK Sars-CoV-2 pandemic lockdown: An assessment of telemedicine and impact on health. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2021, 37, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prato, A.P.; Conforti, A.; Almstrom, M.; Van Gemert, W.; Scuderi, M.G.; Khen-Dunlop, N.; Draghici, I.; Mendoza-Sagaon, M.; Prades, C.G.; Chiarenza, F.; et al. Management of COVID-19-Positive Pediatric Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Surgical Procedures: Systematic Review and Recommendations of the Board of European Society of Pediatric Endoscopic Surgeons. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-S.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Wei, Y.-D.; Liu, C. Recommendations for perinatal and neonatal surgical management during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 2893–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, C.; Masieri, L.; Castagnetti, M.; Crocetto, F.; Escolino, M. Letter to the Editor: Robot-Assisted and Minimally Invasive Pediatric Surgery and Urology During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Short Literature Review. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2020, 30, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akobeng, A.K.; Grafton-Clarke, C.; Abdelgadir, I.; Twum-Barimah, E.; Gordon, M. Gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19 in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Gastroenterol. 2020, 12, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götzinger, F.; Santiago-Garcia, B.; Fumadó-Pérez, V.; Brinkmann, F.; Tebruegge, M. The ability of the neonatal immune response to handle SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng-Ramos, G.; Cronin, J.A.; Heitmiller, E.; Delaney, M.; Sandler, A.; Kelly, S.M.; Mo, Y.; DeBiasi, R.; Pestieau, S.R. Implementation and expansion of a preoperative COVID-19 testing process for pediatric surgical patients. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2020, 30, 952–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idham, Y.; Paramita, V.M.W.; Fauzi, A.R.; Dwihantoro, A.; Makhmudi, A. The Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric surgery practice: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 59, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindi, E.; Cruccetti, A.; Ilari, M.; Mariscoli, F.; Carnielli, V.; Simonini, A.; Cobellis, G. Meckel’s diverticulum perforation in a newborn positive to Sars-Cov-2. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 62, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadin, Z.; Halasa, N.; McHenry, R.; Varjabedian, R.; Lynch, T.L.; Chen, H.; Ghani, M.O.A.; Schmitz, J.E.; Sucre, J.; Isenberg, K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Testing of Aerosols Emitted During Pediatric Minimally Invasive Surgery: A Prospective, Case-Controlled Study. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 2710–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadian, Y.S.; Ali, M.; Kumar, C.; Kajal, P. Surgical Neonates with Coronavirus Infectious Disease-19 Infection. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2022, 19, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, S.C.; Loera, J.M.; Shah, S.R.; Vogel, A.M.; Fallon, S.C.; Glover, C.D.; Monson, L.A.; Enochs, J.A.; Hollier, L.H.; Lopez, M.E. Favorable postoperative outcomes for children with COVID-19 infection undergoing surgical intervention: Experience at a free-standing children’s hospital. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 56, 2078–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Duarte, I.; Evans, A.S.; Alder, A.C.; Vernon, M.C.; Szmuk, P.; Rebstock, S. An unexpected COVID-19 diagnosis during emergency surgery in a neonate. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2021, 31, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saynhalath, R.; Alex, G.; Efune, P.N.; Szmuk, P.; Zhu, H.; Sanford, E.L. Anesthetic Complications Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Pediatric Patients. Anesthesia Analg. 2021, 133, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Ahmed, A.N.U.F.; Sarkar, P.K.F.; Bipul, M.R.A.D.; Ghosh, K.; Rahman, S.W.M.; Rahman, H.D.; Hooda, Y.; Ahsan, N.M.; Malaker, R.M.; et al. The Direct and Indirect Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Infections on Neonates. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, e398–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.R.; Ramji, J.; Vaghela, M.M.; Mehta, C.; Vohra, A.; Joshi, R.S. Challenges and Changes in Pediatric Surgical Practice during the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 27, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarcă, E.; Aprodu, S. Past and present in omphalocele treatment in Romania. Chirurgia 2014, 109, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ţarcă, E.; Roșu, S.T.; Cojocaru, E.; Trandafir, L.; Luca, A.C.; Lupu, V.V.; Moisă, Ș.M.; Munteanu, V.; Butnariu, L.I.; Ţarcă, V. Statistical Analysis of the Main Risk Factors of an Unfavorable Evolution in Gastroschisis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: 10th Revision (ICD-10); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- EUROCAT. Guide 1.4: Instruction for the Registration and Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies. Ispra, Italy: European Commission, Joint Research Centre. 2024. Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/system/files/public/JRC-EUROCAT-Full%20Guide%201%204%20version%2022-Nov-2021.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Heidarzadeh, M.; Taheri, M.; Mazaheripour, Z.; Abbasi-Khameneh, F. The incidence of congenital anomalies in newborns before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, N.K.M.; Lake, R.M.; Englum, B.R.M.; Turner, D.J.; Siddiqui, T.; Mayorga-Carlin, M.; Sorkin, J.D.; Lal, B.K. COVID-19 Vaccination Associated with Reduced Postoperative SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Morbidity. Ann. Surg. 2021, 275, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paidas, M.; Hussain, H.; Ramamoorthy, R.; Masciarella, A.D.; Di Gregorio, D.; Ravelo, N.; Chen, P.; Kwal, J.; Jayakumar, A. 1100 Major congenital malformation in an experimental mouse model of COVID-19. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S577–S578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, M.C.; Söderling, J.; Örtqvist, A.K.; Andersen, A.-M.N.; Stephansson, O.; E Håberg, S.; Urhoj, S.K. Covid-19 infection and vaccination during first trimester and risk of congenital anomalies: Nordic registry based study. BMJ 2024, 386, e079364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, C.; Carruthers, J.; Denny, C.; Donaghy, J.; Hopcroft, L.E.M.; Hopkins, L.; Goulding, A.; Lindsay, L.; McLaughlin, T.; Moore, E.; et al. A population-based matched cohort study of major congenital anomalies following COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: An international cohort study. Lancet 2020, 396, 10243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandibur, T.E.; Kundnani, N.R.; Boia, M.; Nistor, D.; Velimirovici, D.M.; Mada, L.; Manea, A.M.; Boia, E.R.; Neagu, M.N.; Popoiu, C.M. Does COVID-19 Infection during Pregnancy Increase the Appearance of Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformations in Neonates? Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covid-19. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Goodman, L.F.; Yu, P.T.; Guner, Y.; Awan, S.; Mohan, A.; Ge, K.; Chandy, M.; Sánchez, M.; Ehwerhemuepha, L. Congenital anomalies and predisposition to severe COVID-19 among pediatric patients in the United States. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 96, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, Y. Postoperative outcomes of pediatric patients with perioperative COVID-19 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Anesthesia 2024, 38, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Archer, P.; von Ungern-Sternberg, B.S. Pediatric anesthetic implications of COVID-19—A review of current literature. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2020, 30, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.E.; Blumberg, T.J.; Adler, A.C.; Fazal, F.Z.; Talwar, D.; Ellingsen, K.; Shah, A.S. Incidence of COVID-19 in Pediatric Surgical Patients Among 3 US Children’s Hospitals. JAMA Surgery 2020, 155, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.M.; Disma, N.; Matava, C.T. Coronavirus disease 2019 and pediatric anesthesia. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 34, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasbey, J.; COVIDSurg and GlobalSurg Collaboratives. Peri-operative outcomes of surgery in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepogodiev, D. Favourable perioperative outcomes for children with SARS-CoV-2. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, e644–e645. [Google Scholar]

- Al Farooq, A.; Kabir, S.M.H.; Chowdhury, T.K.; Sadia, A.; Alam, A.; Farhad, T. Changes in children’s surgical services during the COVID-19 pandemic at a tertiary-level government hospital in a lower middle-income country. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamir, N.; Taqvi, S.M.R.H.; Akhtar, J.; Saddal, N.S.; Anwar, M. Effect of Strict Lockdown on Pediatric Surgical Services and Residency Programme during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2021, 31, S75–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise, K.; Tachimori, H.; Fujishiro, J.; Tomita, H.; Suzuki, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Miyata, H.; Fuchimoto, Y. Impact of the novel coronavirus infection on pediatric surgery: An analysis of data from the National Clinical Database. Surg. Today 2024, 54, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1097–1103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duceac, L.D.; Banu, E.A.; Baciu, G.; Lupu, V.V.; Ciomaga, I.M.; Tarca, E.; Mitrea, G.; Ichim, D.L.; Damir, D.; Constantin, M.; et al. Assessment of Bacteria Resistance According to Antibiotic Chemical Structure. Rev. de Chim. 2019, 70, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Namat, R.; Duceac, L.D.; Chelaru, L.; Dimitriu, C.; Bazyani, A.; Tarus, A.; Bacusca, A.; Roșca, A.; Al Namat, D.; Livanu, L.I.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Oxidative Stress and Cardiac Fibrosis Biomarkers in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction (STEMI), a Single-Center Experience Analysis. Life 2024, 14, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandibur, T.E.; Kundnani, N.R.; Ramakrishna, K.; Mederle, A.; Manea, A.M.; Boia, M.; Popoiu, M.C. Comparison of One-Year Post-Operative Evolution of Children Born of COVID-19-Positive Mothers vs. COVID-19-Negative Pregnancies Having Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation and Having Received Proper Parenteral Nutrition during Their Hospital Stay. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors/Reference | Journal | Year Published/ Analyzed Period | Country | Study Design | No. of Patients | Surgical Diagnosis | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bindi et al. [24] | Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports | 2020 | Italy | Case report | 1 | Meckel’s diverticulum | Discharged home |

| Haddadin et al. [25] | The American Surgeon | 2022 20 July–21 June | USA | Prospective | 2 | CHPS HD | Discharged home |

| Kadian et al. [26] | African Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 2022 | India | Case series | 4 | EA-TEF (n = 2) Low ARM DA with pyloric web | Discharged home |

| Mehl et al. [27] | Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 2021 April–20 August | USA | Retrospective | 3 | CHPS (n = 3) | Discharged home |

| Moreno-Duarte et al. [28] | Pediatric Anesthesia | 2021 | USA | Case report | 1 | DA | Discharged home |

| Saynhalath et al. [29] | Pediatric Anesthesiology | 2021 April–20 September | USA | Retrospective | 1 | DA | No data |

| Saha et al. [30] | The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal | 2020 March–20 July | Bangladesh | Case series | 2 | ARM | 1 * transfer to a COVID-19-designated hospital postoperatively 1 * death prior to surgical input (early neonatal sepsis) |

| Shah et al. [31] | J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg | 2022 20 March–21 July | India | Cohort | 15 | TEF (n = 8) Intestinal atresia (n = 3) High ARM (n = 3) CHPS (n = 1) | Partially reported: 24 patients recovered; 7 died or lost to follow-up (diagnoses unspecified) * |

| Surgical Diagnosis | No. of Patients (%) | Surgical Approach | Surgical Procedure | Surgical Invasiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARM | 3 (10.3%) | No data | No data [31] | NA |

| 1 (3.44%) | NA | NA [30] | NA | |

| 2 (6.89%) | Transanally | Anoplasty (V-Y) | Moderate | |

| CHPS | 4 (13.79%) | Minimally invasive | Pyloromyotomy | Low |

| 1 (3.44%) | No data | No data [31] | NA | |

| DA | 2 (6.89%) | Open | Duodenoduodenal (+pylorojejunal anastomosis) | High |

| 1 (3.44%) | Minimally invasive −>converted to open | Duodenoduodenal anastomosis | High | |

| HD | 1 (3.44%) | Minimally invasive | Resection pull-through | Moderate |

| Intestinal atresia | 3 (10.3%) | No data | No data [31] | NA |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | 1 (3.44%) | Open | Diverticulum resection with ileo-ileal end-to-end anastomosis | High |

| EA ± TEF | 2 (6.89%) | Open | End-to-end esophageal anastomosis± fistula closure | High |

| 8 (27.55%) | No data | No data [31] | NA | |

| Total | 29 |

| Surgical Invasiveness | COVID-19-Related Complications | Surgery-Related Complications | Total (n) | % of Total Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0 | 0 | 4 | 30.8% |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | 3 | 23.01% |

| High | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 6 | 46.01% |

| Total | 2 | 1 | 13 | |

| Fisher–Freeman–Halton exact p = 0.3 | Fisher–Freeman–Halton exact p = 0.47 | |||

| No data/No surgery | - | - | 16 |

| Authors | No. of Patients | Age | Clinical Status | Reason for COVID-19 Testing | Type of COVID-19 Testing | COVID-19 Test Result | Diagnosis | Complications | Mother’s COVID-19 Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | Intraop | Postop | COVID-19 | Surgical | ||||||||

| Bindi et al. [24] | 1 | 3 days | No symptoms | Symptomatic referral pediatrician | No data | Not tested | Not tested | Positive | Meckel’s diverticulum | No | Yes | Negative |

| Haddadin et al. [25] | 2 | 6 weeks | No symptoms | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive | Positive | Not tested | CHPS | No | No | No data |

| 1.25 years | No symptoms | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive | Positive | Not tested | HD | No | No | No data | ||

| Kadian et al. [26] | 4 | 2 days | No symptoms | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive | Positive | Neg POD 5 | ARM | No | No | Negative |

| 3 days | No symptoms | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive on admission/Neg at DOL 3 and 4 | Neg | Not tested | EA-TEF | No | No | No data | ||

| 1 day | No symptoms | Protocol | No data | Positive at DOL 7 + 8/Neg at DOL 13 | Neg | Not tested | DA with pyloric web | No | No | Positive after delivery (day 5) | ||

| 5 days | No symptoms | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive on admission/Neg at DOL 4 and 6 | Neg | Not tested | EA-TEF | No | No | Negative | ||

| Mehl et al. [27] | 3 | 4–6 weeks | No data | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive | Positive | No data | CHPS | No | No | No data |

| Moreno-Duarte et al. [28] | 1 | 4 days | No symptoms | Protocol | Biofire Panel | Pending | Positive | No data | DA | Yes | No | Negative |

| Saynhalath et al. [29] | 1 | 4 days | No data | Protocol | RT-PCR/Biofire Panel//Rapid test | Positive | Positive | No data | DA | Yes | No | No data |

| Senjuti et al. [30] | 2 | 2 days | Early onset of neonatal sepsis | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive | NA | NA | ARM (imperforate anus) | Succumbed at DOL 3 (neonatal sepsis) | N/A | Not tested |

| 1 day | No symptoms | Protocol | RT-PCR | Not tested | Not tested | Positive (POD2) | ARM (Ano cutaneous fistula) | No | No | Not tested | ||

| Shah et al. [31] | 15 | Neonates | No data | Protocol | RT-PCR | Positive/pending * | Positive/ pending * | No data | EA-TEF (n = 8) Intestinal atresia (n = 3) ARM (n = 3) CHPS (n = 1) | No | No *** | No data |

| Reference No | Author | COVID-19 Protective Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| [24] | Bindi et al. | Patients’ isolation; staff swab-tested; emphasize pre-op screening to limit exposure |

| [25] | Haddadin et al. | Used smoke evacuation/filtration; found no SARS-CoV-2 in aerosols but kept strict containment practices |

| [26] | Kadian et al. | Dedicated COVID-19-neonates intensive care and operating room; PPE for all staff; defer non-urgent cases until negative test; urgent cases under full COVID protocol |

| [27] | Mehl et al. | Institutional COVID perioperative pathway; testing and triage before surgery; safe workflows to continue urgent surgeries |

| [28] | Moreno-Duarte et al. | Airborne PPE (N95, gown, goggles, gloves); minimize staff during intubation/extubation; HEPA filters in circuit |

| [30] | Saha et al. | Routine SARS-CoV-2 testing for surgical patients; isolation and referral to COVID-19-dedicated hospitals |

| [29] | Saynhalath et al. | Highlighted increased peri anesthetic respiratory complications; reinforced airborne-level PPE and airway planning |

| [31] | Shah et al. | Dedicated COVID OR/team; full PPE; minimize staff during intubation/extubation; smoke evacuation; RT-PCR before elective cases |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stratulat-Chiriac, I.; Țarcă, E.; Chistol, R.O.; Halip, I.-A.; Țarcă, V.; Furnică, C. Association Between Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation Outcome and Largely Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pediatric Patients—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238533

Stratulat-Chiriac I, Țarcă E, Chistol RO, Halip I-A, Țarcă V, Furnică C. Association Between Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation Outcome and Largely Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pediatric Patients—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238533

Chicago/Turabian StyleStratulat-Chiriac, Iulia, Elena Țarcă, Raluca Ozana Chistol, Ioana-Alina Halip, Viorel Țarcă, and Cristina Furnică. 2025. "Association Between Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation Outcome and Largely Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pediatric Patients—A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238533

APA StyleStratulat-Chiriac, I., Țarcă, E., Chistol, R. O., Halip, I.-A., Țarcă, V., & Furnică, C. (2025). Association Between Congenital Gastrointestinal Malformation Outcome and Largely Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pediatric Patients—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238533