Efficacy of Injectable Calcium Composite Bone Substitute Augmentation for Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Fractures: A Prospective, Non-Randomized Controlled Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

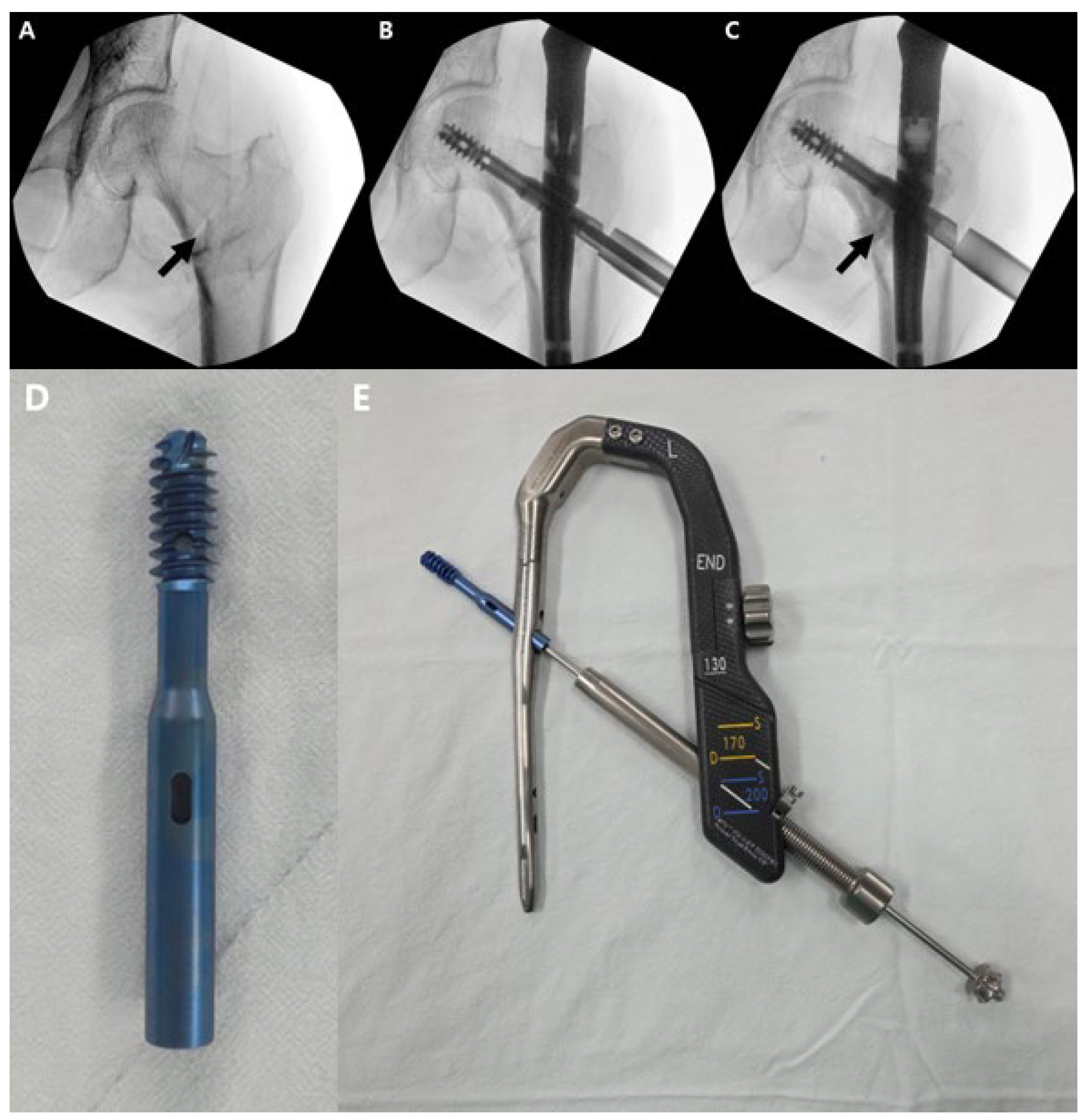

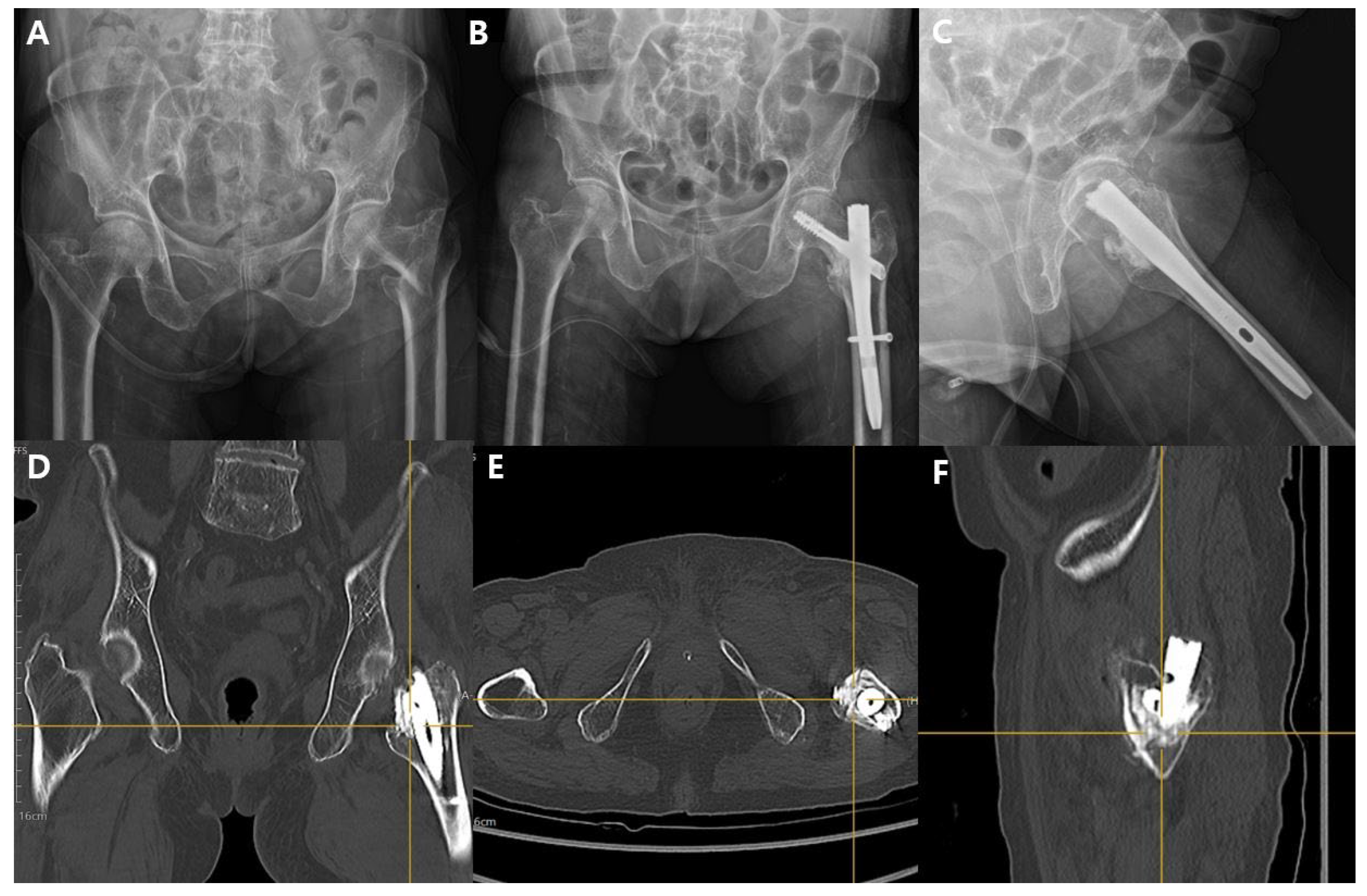

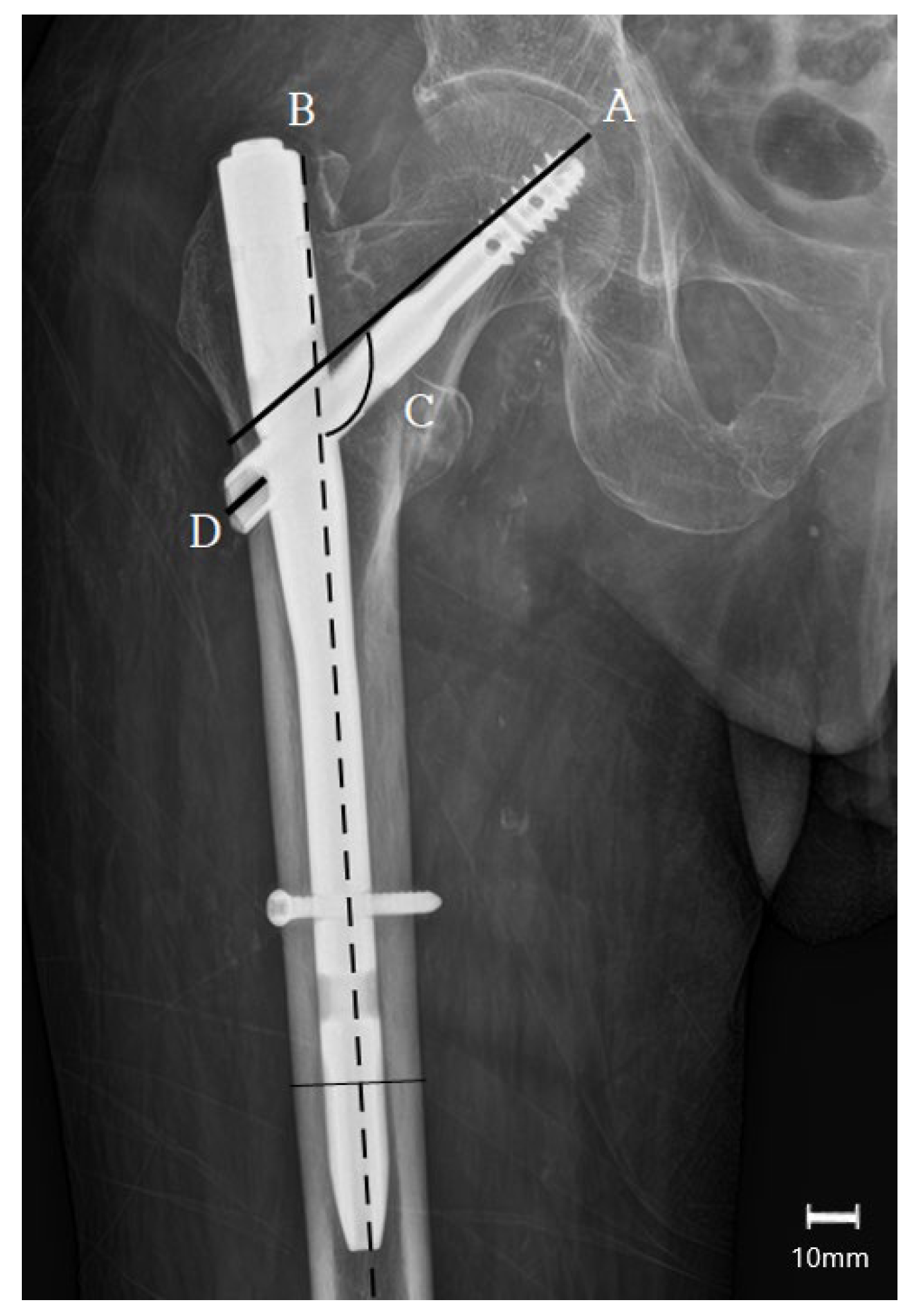

2.1. Surgical Technique

2.2. Postoperative Management

2.3. Data Collection

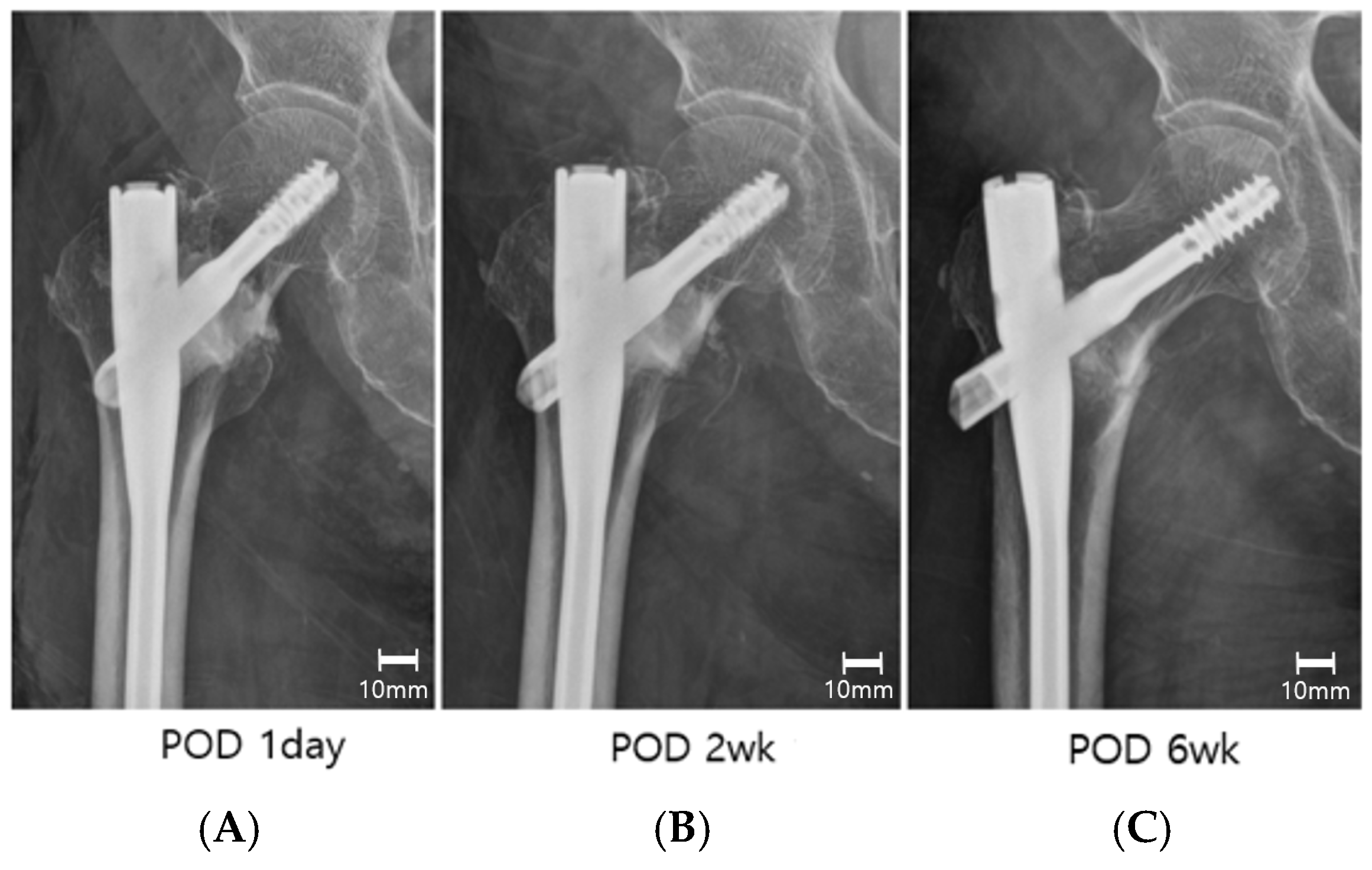

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ITF | Intertrochanteric fracture. |

| ICCBS | Injectable calcium composite bone substitute. |

| TAD | Tip–apex distance. |

| NSA | Neck shaft angle. |

| mHHS | Modified Harris hip score. |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale. |

| FAC | Functional ambulation category. |

| MCID | Minimal clinically important differences. |

References

- Haentjens, P.; Magaziner, J.; Colón-Emeric, C.S.; Vanderschueren, D.; Milisen, K.; Velkeniers, B.; Boonen, S. Meta-analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guideline CG124 N. Hip Fracture: Management (Update). 2023. Available online: https://www.apta.org/patient-care/evidence-based-practice-resources/cpgs/hip-fracture-management-nice-cg124 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Switzer, J.A.; O’Connor, M.I. AAOS Management of Hip Fractures in Older Adults Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline. JAAOS-J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, e1297–e1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, K.J.; Goubar, A.; Almilaji, O.; Martin, F.C.; Potter, C.; Jones, G.D.; Sackley, C.; Ayis, S. Discharge after hip fracture surgery by mobilisation timing: Secondary analysis of the UK National Hip Fracture Database. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.T.; Jakobsen, T.L.; Nielsen, J.W.; Jørgensen, L.M.; Nienhuis, R.J.; Jønsson, L.R. Cumulated Ambulation Score to evaluate mobility is feasible in geriatric patients and in patients with hip fracture. Dan. Med. J. 2012, 59, A4464. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, C.M.; Harris-Hayes, M.; Kristensen, M.T.; Overgaard, J.A.; Herring, T.B.; Kenny, A.M.; Mangione, K.K. Physical Therapy Management of Older Adults with Hip Fracture. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, CPG1–CPG81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, M.L. Mechanical Complications After Intramedullary Fixation of Extracapsular Hip Fractures. JAAOS - J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, e1550–e1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojan, A.J.; Beimel, C.; Taglang, G.; Collin, D.; Ekholm, C.; Jönsson, A. Critical factors in cut-out complication after Gamma Nail treatment of proximal femoral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Bonomo, M.; Valpiani, G.; Salvatori, G.; Gildone, A.; Lorusso, V.; Massari, L. A six-year retrospective analysis of cut-out risk predictors in cephalomedullary nailing for pertrochanteric fractures: Can the tip-apex distance (TAD) still be considered the best parameter? Bone Jt. Res. 2017, 6, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgaertner, M.R.; Curtin, S.L.; Lindskog, D.M.; Keggi, J.M. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1995, 77, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Nakayama, S.; Hara, M.; Koizumi, W.; Itabashi, T.; Saito, M. Tip-Apex Distance Is Most Important of Six Predictors of Screw Cutout After Internal Fixation of Intertrochanteric Fractures in Women. JBJS Open Access 2017, 2, e0022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotfried, Y. Integrity of the Lateral Femoral Wall in Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures: An Important Predictor of a Reoperation. JBJS 2007, 89, 2552–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotfried, Y. The lateral trochanteric wall: A key element in the reconstruction of unstable pertrochanteric hip fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2004, 425, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompen, I.F.; Knobe, M.; Link, B.-C.; Beeres, F.J.P.; Baumgaertner, R.; Diwersi, N.; Migliorini, F.; Nebelung, S.; Babst, R.; van de Wall, B.J.M. Cement augmentation for trochanteric femur fractures: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and observational studies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattsson, P.; Alberts, A.; Dahlberg, G.; Sohlman, M.; Hyldahl, H.C.; Larsson, S. Resorbable cement for the augmentation of internally-fixed unstable trochanteric fractures. A prospective, randomised multicentre study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2005, 87, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammerlander, C.; Hem, E.S.; Klopfer, T.; Gebhard, F.; Sermon, A.; Dietrich, M.; Bach, O.; Weil, Y.; Babst, R.; Blauth, M. Cement augmentation of the Proximal Femoral Nail Antirotation (PFNA)—A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Injury 2018, 49, 1436–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Ogawa, T.; Banno, M.; Watanabe, J.; Noda, T.; Schermann, H.; Ozaki, T. Cement augmentation of internal fixation for trochanteric fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Fujii, T.; Tomita, Y. Effectiveness of Cement Augmentation on Early Postoperative Mobility in Patients Treated for Trochanteric Fractures with Cephalomedullary Nailing: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, T.W.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, O.G.; Heo, K.S.; Shon, W.Y. Usefulness of Synthetic Osteoconductive Bone Graft Substitute with Zeta Potential Control for Intramedullary Fixation with Proximal Femur Nail Antirotation in Osteoporotic Unstable Femoral Intertrochanteric Fracture. Hip Pelvis 2021, 33, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Ni, H.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Tang, H.; Dong, Y. Comparison of Baumgaertner and Chang reduction quality criteria for the assessment of trochanteric fractures. Bone Jt. Res. 2019, 8, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, W.H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: Treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1969, 51, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.K.; Queen, R.M.; Butler, R.J.; Bolognesi, M.P.; Lowry Barnes, C. Are Range of Motion Measurements Needed When Calculating the Harris Hip Score? J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskisson, E.C. Measurement of pain. Lancet 1974, 2, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.K.; Gill, K.M.; Magliozzi, M.R.; Nathan, J.; Piehl-Baker, L. Clinical gait assessment in the neurologically impaired. Reliability and meaningfulness. Phys. Ther. 1984, 64, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. Functional Ambulation Category (FAC). RehabMeasures Database. 2024. Available online: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/functional-ambulation-category (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Chinzei, N.; Hiranaka, T.; Niikura, T.; Fujishiro, T.; Hayashi, S.; Kanzaki, N.; Hashimoto, S.; Sakai, Y.; Kuroda, R.; Kurosaka, M. Accurate and Easy Measurement of Sliding Distance of Intramedullary Nail in Trochanteric Fracture. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 7, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, J.W.; Kim, M.W.; Noh, Y.M.; Seo, H.E.; Lee, D.H. Using Risk Factors and Preoperative Inflammatory Markers to Predict 3-Year Mortality in Patients with Unstable Intertrochanteric Femur Fractures. Hip Pelvis 2025, 37, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Oh, J.H.; Han, I.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, S.W. Grafting using injectable calcium sulfate in bone tumor surgery: Comparison with demineralized bone matrix-based grafting. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2011, 3, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, V.; Milano, G.; Pagano, E.; Barba, M.; Cicione, C.; Salonna, G.; Lattanzi, W.; Logroscino, G. Bone substitutes in orthopaedic surgery: From basic science to clinical practice. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 2445–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez de Grado, G.; Keller, L.; Idoux-Gillet, Y.; Wagner, Q.; Musset, A.M.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; Bornert, F.; Offner, D. Bone substitutes: A review of their characteristics, clinical use, and perspectives for large bone defects management. J. Tissue Eng. 2018, 9, 2041731418776819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.H.K.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Bao, C.; Chen, Q.; Weir, M.D.; Chow, L.C.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Reynolds, M.A. Calcium phosphate cements for bone engineering and their biological properties. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 17056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermon, A.; Hofmann-Fliri, L.; Zderic, I.; Agarwal, Y.; Scherrer, S.; Weber, A.; Altmann, M.; Knobe, M.; Windolf, M.; Gueorguiev, B. Impact of Bone Cement Augmentation on the Fixation Strength of TFNA Blades and Screws. Medicina 2021, 57, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhart, S.; Schmoelz, W.; Blauth, M.; Lenich, A. Biomechanical effect of bone cement augmentation on rotational stability and pull-out strength of the Proximal Femur Nail Antirotation™. Inj.-Int. J. Care Inj. 2011, 42, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiss, F.; Apelt, D.; Brand, B.; Kutter, A.; Zlinszky, K.; Bohner, M.; Matter, S.; Frei, C.; Auer, J.A.; von Rechenberg, B. Biocompatibility and resorption of a brushite calcium phosphate cement. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4383–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker. Pro-Dense Injectable Regenerative Graft: Technical Monograph (Mechanism of Action); Technical Monograph; Stryker: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Summary—PRO-DENSE Bone Graft Substitute (K132656); Regulatory Summary; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, H.; Pandey, A.; Agarwal, R.; Mehra, H.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, A. Application of calcium sulfate as graft material in implantology and maxillofacial procedures: A review of literature. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 15, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, S.; Cathro, P.; Ivanovski, S.; Muhammad, N. Biomimetic bone grafts and substitutes: A review of recent advancements and applications. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2023, 6, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.S.; Phull, S.S.; Bal, B.S.; Towler, M.R. Bone void filler materials for augmentation in comminuted fractures: A comprehensive review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangkanjanavelukul, P.; Thaitalay, P.; Srisuwan, S.; Petchwisai, P.; Thasanaraphan, P.; Saramas, Y.; Nimarkorn, K.; Warojananulak, W.; Kanchanomai, C.; Rattanachan, S.T. Feasibility biomechanical study of injectable Biphasic Calcium Phosphate bone cement augmentation of the proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) for the treatment of two intertrochanteric fractures using cadaveric femur. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2024, 10, 045043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Group A (ICCBS Augmentation) (n = 78) | Group B (Non-Augmentation) (n = 75) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 78.3 ± 8.09 | 76.2 ± 7.94 | 0.17 |

| Sex | 0.74 | ||

| Male | 28 | 24 | |

| Female | 50 | 51 | |

| Side | 0.80 | ||

| Right | 38 | 34 | |

| Left | 40 | 41 | |

| Bone mineral density, T-score (mean ± SD) | −3.10 ± 0.99 | −3.16 ± 0.70 | 0.67 |

| Baumgaertner criteria | 0.61 | ||

| Good | 41 | 38 | |

| Acceptable | 32 | 33 | |

| Poor | 5 | 4 | |

| AO/OTA classification | 0.56 | ||

| 31-A1 | 14 | 15 | |

| 31-A2 | 38 | 41 | |

| 31-A3 | 26 | 19 | |

| Ambulatory status | 0.58 | ||

| Without assistance | 34 | 32 | |

| With assistance | 44 | 43 | |

| Follow-up duration, months (mean ± SD) | 12 ± 3.4 | 14 ± 4.6 | 0.2 |

| Outcome | Group A (n = 78) | Group B (n = 75) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to radiographic union, weeks (mean ± SD) | 11.2 ± 5.6 | 13.4 ± 6.2 | 0.28 |

| Lagscrew sliding, mm (mean ± SD) | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 3.2 | 0.01 * |

| Varus collapse (Δ neck–shaft angle), degrees (mean ± SD) | 3.3 ± 4.6 | 8.2 ± 5.3 | 0.02 * |

| Fixation failure | 2 | 3 | 0.67 |

| Outcome /Time Point | Group A (n = 78) | Group B (n = 75) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Harris Hip Score (mean ± SD) | |||

| Postoperative | |||

| 2 weeks | 42.2 ± 5.34 | 31.52 ± 6.12 | <0.001 * |

| 6 weeks | 59.3 ± 6.12 | 49.21 ± 4.23 | 0.01 * |

| 3 months | 75.2 ± 7.65 | 71.34 ± 8.12 | 0.23 |

| 6 months | 77.6 ± 8.52 | 74.4 ± 9.56 | 0.31 |

| 12 months | 79.6 ± 9.14 | 80.4 ± 7.96 | 0.58 |

| Pain—VAS 0–10 at rest (mean ± SD) | |||

| Postoperative | |||

| 2 weeks | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 0.001 * |

| 6 weeks | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 0.02 * |

| 3 months | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 0.24 |

| 6 months | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.38 |

| 12 months | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.55 |

| Pain—VAS 0–10 during mobilization (mean ± SD) | |||

| Postoperative | |||

| 2 weeks | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | <0.01 * |

| 6 weeks | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 0.04 * |

| 3 months | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 0.24 |

| 6 months | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 0.16 |

| 12 months | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 0.34 |

| Ambulatory status—FAC (0–6; higher = better) (mean ± SD) | |||

| Postoperative | |||

| 2 weeks | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | <0.001 * |

| 6 weeks | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 0.08 |

| 3 months | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 0.27 |

| 6 months | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 0.31 |

| 12 months | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 4.7 ± 2.1 | 0.60 |

| Complication | Group A (n = 78) | Group B (n = 75) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial infection, n | 2 | 1 | 0.58 |

| Deep infection, n | 0 | 0 | - |

| Wound dehiscence, n | 3 | 2 | 0.68 |

| Urinary tract infection, n | 7 | 6 | 0.83 |

| Venous thrombosis, n | 2 | 2 | 0.97 |

| Transfusion, n | 21 | 26 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.H.; Kim, H.T.; Sohn, H.M.; Kim, G.C.; Jin, E.J.; Jo, S. Efficacy of Injectable Calcium Composite Bone Substitute Augmentation for Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Fractures: A Prospective, Non-Randomized Controlled Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8536. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238536

Lee CH, Kim HT, Sohn HM, Kim GC, Jin EJ, Jo S. Efficacy of Injectable Calcium Composite Bone Substitute Augmentation for Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Fractures: A Prospective, Non-Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8536. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238536

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Chae Hun, Hyoung Tae Kim, Hong Moon Sohn, Gwui Cheol Kim, Eun Ju Jin, and Suenghwan Jo. 2025. "Efficacy of Injectable Calcium Composite Bone Substitute Augmentation for Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Fractures: A Prospective, Non-Randomized Controlled Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8536. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238536

APA StyleLee, C. H., Kim, H. T., Sohn, H. M., Kim, G. C., Jin, E. J., & Jo, S. (2025). Efficacy of Injectable Calcium Composite Bone Substitute Augmentation for Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Fractures: A Prospective, Non-Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8536. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238536