Protocol for a Single-Arm Pilot Clinical Trial: Developing and Evaluating a Machine Learning Opioid Prediction & Risk-Stratification E-Platform (DEMONSTRATE)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting, Participants and Recruitment

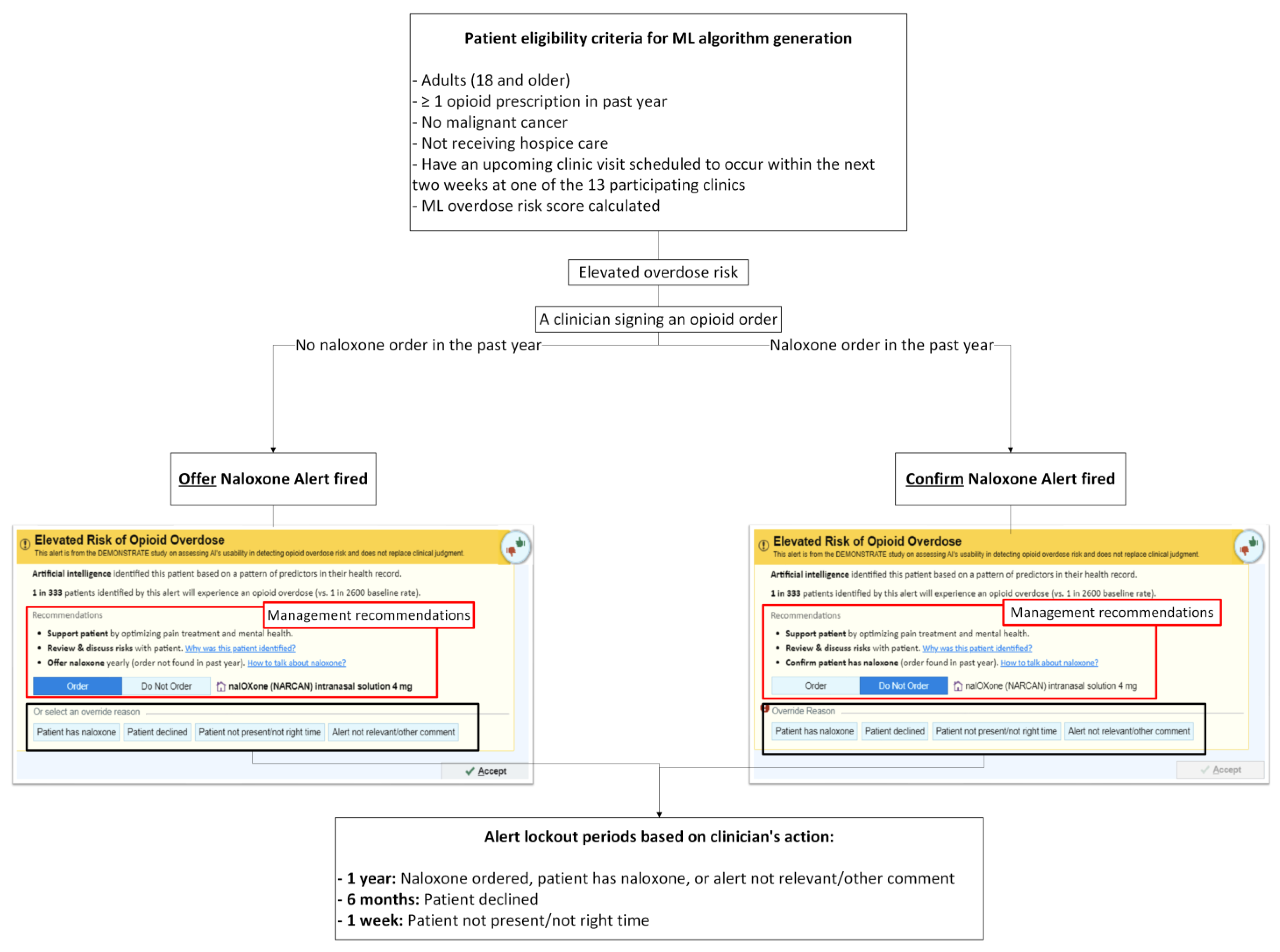

2.3. Patient Eligibility Criteria for ML Overdose Risk Score Generation

Overview of the ML Overdose Risk Prediction Model

2.4. ML-Driven Overdose Prevention Alert Intervention

2.4.1. Alert User Interface (UI)

- (1)

- No naloxone order in the past year—“Order Naloxone Overdose Prevention Alert” (Figure 1A): Recommends ordering naloxone and provides three mitigation strategies:

- “Support patient by optimizing pain treatment and mental health”;

- “Review & discuss risks with patient”;

- “Offer naloxone yearly (order not found in past year).”

- (2)

- Naloxone order in the past year—“Confirm Patient Has Naloxone Overdose Prevention Alert” (Figure 1B): Defaults to “Do Not Order” and prompts the PCP to verify that the patient already possesses naloxone.

2.4.2. Alert Exposure and Workflow

- (1)

- No naloxone order/fill record in the past year: When a patient has not had a naloxone order/fill in the past year, “Order Naloxone Overdose Prevention Alert” (Figure 1A) is triggered at the time the PCP signs an opioid order. This version recommends naloxone prescribing and presents three management strategies:

- “Support patient by optimizing pain treatment and mental health”;

- “Review & discuss risks with patient”;

- “Offer naloxone yearly (order not found in past year).”

The default selection is “Order Naloxone.” PCPs may override by selecting “Do Not Order” or choosing a pre-labeled override reason, including:- “Patient has naloxone”,

- “Patient declined”,

- “Patient not present/not the right time”,

- “Alert not relevant/other comment” (free text required).

- (2)

- Naloxone order/fill documented in the past year: When a patient had a naloxone order/fill in the past year, “Confirm Patient Has Naloxone Overdose Prevention Alert” (Figure 1B) appears when the PCP signs an opioid order. This version defaults to “Do Not Order” and prompts the PCP to verify that the patient possesses naloxone. If the PCP elects to prescribe naloxone, they must actively select “Order.” PCPs may choose a pre-labeled override reason, including: “Patient has naloxone”, “Patient declined”, “Patient not present/not the right time,” and “Alert not relevant/other comment”.

- 1 year—Naloxone ordered, or a PCP chooses an override reason “Patient has naloxone” or “Alert not relevant/other comment.” Free-text entry is enabled for “Alert not relevant/other comment”.

- 6 months— A PCP chooses an override reason “Patient declined.”

- 1 week— A PCP chooses an override reason “Patient not present/not the right time.”

2.5. Outcomes

2.5.1. Primary Patient-Level Outcomes

- (1)

- Evidence of naloxone access (order, fill, or documentation of possession [e.g., PCP selection of button ‘patient has naloxone’]),

- (2)

- Absence of opioid overdose diagnoses and naloxone administration,

- (3)

- Absence of ED visits or hospitalizations due to opioid overdose or OUD,

- (4)

- Absence of overlapping opioid and benzodiazepine use within a 7-day window,

- (5)

- Absence of opioid use ≥50 MME daily average,

- (6)

- Receipt of referrals to non-pharmacological pain management (e.g., physical therapy, chiropractic care).

2.5.2. Primary PCP-Level Outcomes

- (1)

- the Overdose Prevention Alert’s information was clear,

- (2)

- the alert was easy to use,

- (3)

- the alert helps identify patients at elevated overdose risk,

- (4)

- the alert helps understand patient’s overdose risk,

- (5)

- the alert provides risk management recommendations,

- (6)

- the alert identifies the right patients with elevated overdose risk,

- (7)

- the alert notifies the correct healthcare team member (i.e., PCPs),

- (8)

- a pop-up alert is an appropriate notification approach,

- (9)

- signing an opioid order is the right time for the alert,

- (10)

- alert frequency is appropriate,

- (11)

- I prefer the Overdose Prevention Alert over the legacy naloxone alert (see picture),

- (12)

- I want the Overdose Prevention Alert to continue to operate in my EHR.

2.5.3. Secondary Alert Use-Related Outcomes

- Penetration: Penetration outcomes measure the extent to which the alert reached its intended users and patients. These include the total number of alert appearances (overall and by alert version: “Order Naloxone” vs. “Confirm Naloxone”), the percentage of ML-flagged elevated-risk patients who received ≥1 alert, the average number of alerts per alerted patient, and the percentage of PCPs at participating clinics who encountered at least one alert.

- Adoption: Adoption outcomes evaluate the extent to which clinicians accepted or acted upon the alert recommendations. Measures include the percentage of alerts resulting in an accepted naloxone order, patient-level naloxone acceptance (≥1 accepted naloxone order per alerted patient), and the percentage of alerts for which a naloxone order was initially selected but ultimately unsigned (e.g., deleted after clicking “Accept”).

- Appropriateness: Appropriateness outcomes examine whether clinicians perceived the alert as relevant and useful in practice. Measures include the proportion of alerts associated with specific override reasons (“Patient has naloxone,” “Patient declined,” “Patient not present/not the right time,” and “Alert not relevant/other”), patterns of override reasons across clinics and PCPs, and the percentage of alerts accompanied by free-text override comments (with qualitative analysis).

2.6. Sample Size Estimation

2.7. Statistical and Qualitative Analyses

2.7.1. Patient-Level Outcomes

2.7.2. PCP-Level Outcomes

2.7.3. Alert Use-Related Outcomes

2.8. Confidentiality and Safety Monitoring

3. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| DEMONSTRATE | Developing and Evaluating a Machine Learning Opioid Prediction & Risk-Stratification E-Platform |

| ED | Emergency department |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| IDR | Integrated Data Repository |

| IRB | Institutional review board |

| MME | Morphine milligram equivalents |

| ML | Machine learning |

| OUD | Opioid use disorder |

| PCP | Primary care provider |

| PDMP | Prescription drug monitoring program |

| RE-AIM | Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance |

| SaMD | Software as a Medical Device |

| SPIRIT | Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials |

| UI | User interface |

| UF | University of Florida |

| US | United States |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. U.S. Overdose Deaths Decrease Almost 27% in 2024: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/releases/20250514.html (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose Prevention: Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs). 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/php/interventions/prescription-drug-monitoring-programs.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Dowell, D.; Ragan, K.R.; Jones, C.M.; Baldwin, G.T.; Chou, R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, D.; Zhang, K.; Noonan, R.K.; Hockenberry, J.M. Mandatory Provider Review And Pain Clinic Laws Reduce The Amounts Of Opioids Prescribed And Overdose Death Rates. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Ciganic, W.H.; Huang, J.L.; Zhang, H.H.; Weiss, J.C.; Wu, Y.; Kwoh, C.K.; Donohue, J.M.; Cochran, G.; Gordon, A.J.; Malone, D.C.; et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e190968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, J.H.; El-Bassel, N.; Winhusen, T.J.; Jackson, R.D.; Oga, E.A.; Chandler, R.K.; Villani, J.; Freisthler, B.; Adams, J.; Aldridge, A.; et al. Community-Based Cluster-Randomized Trial to Reduce Opioid Overdose Deaths. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 989–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.K.; Sidhu, G.K.; Gupta, K. Current and Future Perspective of Devices and Diagnostics for Opioid and OIRD. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. DOSE-SYS Dashboard: Nonfatal Overdose Syndromic Surveillance Data. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/data-research/facts-stats/dose-dashboard-nonfatal-surveillance-data.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Madras, B.K. The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis: Origins and Recommendations. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo-Ciganic, W.H.; Donohue, J.M.; Hulsey, E.G.; Barnes, S.; Li, Y.; Kuza, C.C.; Yang, Q.; Buchanich, J.; Huang, J.L.; Mair, C.; et al. Integrating human services and criminal justice data with claims data to predict risk of opioid overdose among Medicaid beneficiaries: A machine-learning approach. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Ciganic, W.H.; Huang, J.L.; Zhang, H.H.; Weiss, J.C.; Kwoh, C.K.; Donohue, J.M.; Gordon, A.J.; Cochran, G.; Malone, D.C.; Kuza, C.C.; et al. Using machine learning to predict risk of incident opioid use disorder among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries: A prognostic study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Ciganic, W.H.; Donohue, J.M.; Yang, Q.; Huang, J.L.; Chang, C.Y.; Weiss, J.C.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.H.; Cochran, G.; Gordon, A.J.; et al. Developing and validating a machine-learning algorithm to predict opioid overdose in Medicaid beneficiaries in two US states: A prognostic modelling study. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e455–e465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Florida Clinican and Translational Science Institute. Integrated Data Repository Research Service. 2025. Available online: https://idr.ufhealth.org/about-us/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Joseph, S. Epic’s Market Share: Who Should Control The Levers of Healthcare Innovation? 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sethjoseph/2024/02/26/epics-antitrust-paradox-who-should-control-the-levers-of-healthcare-innovation/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Naderalvojoud, B.; Curtin, C.; Asch, S.M.; Humphreys, K.; Hernandez-Boussard, T. Evaluating the impact of data biases on algorithmic fairness and clinical utility of machine learning models for prolonged opioid use prediction. JAMIA Open 2025, 8, ooaf115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.; Wilson, D.L.; Diiulio, J.; Hall, B.; Militello, L.; Gellad, W.F.; Harle, C.A.; Lewis, M.; Schmidt, S.; Rosenberg, E.I.; et al. Design and development of a machine-learning-driven opioid overdose risk prediction tool integrated in electronic health records in primary care settings. Bioelectron. Med. 2024, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militello, L.G.; Diiulio, J.; Wilson, D.L.; Nguyen, K.A.; Harle, C.A.; Gellad, W.; Lo-Ciganic, W.-H. Using human factors methods to mitigate bias in artificial intelligence-based clinical decision support. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R. The five “rights” of clinical decision support. J. Ahima. 2013, 84, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vegt, A.H.; Scott, I.A.; Dermawan, K.; Schnetler, R.J.; Kalke, V.R.; Lane, P.J. Implementation frameworks for end-to-end clinical AI: Derivation of the SALIENT framework. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2023, 30, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasey, B.; Clifton, D.A.; Collins, G.S.; Denniston, A.K.; Faes, L.; Geerts, B.F.; Liu, X.; Morgan, L.; Watkinson, P.; McCulloch, P. DECIDE-AI: New reporting guidelines to bridge the development-to-implementation gap in clinical artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 186–187. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Cruz Rivera, S.; Moher, D.; Calvert, M.J.; Denniston, A.K.; SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI Working Group. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: The CONSORT-AI extension. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Developing and Evaluating a Machine-Learning Opioid Overdose Prediction & Risk-Stratification Tool in Primary Care (DEMONSTRATE); Identifier NCT06810076; National Library of Medicine (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06810076 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Butcher, N.J.; Monsour, A.; Mew, E.J.; Chan, A.W.; Moher, D.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Terwee, C.B.; Chee-A-Tow, A.; Baba, A.; Gavin, F.; et al. Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Protocols: The SPIRIT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA 2022, 328, 2345–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 1995, 7, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, E.M.; Bisantz, A.M.; Wang, X.; Kim, T.; Hettinger, A.Z. A Work-Centered Approach to System User-Evaluation. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 2021, 15, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. A Tutorial on Multilevel Survival Analysis: Methods, Models and Applications. Int. Stat. Rev. 2017, 85, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food & Drug. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). 2018. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/software-medical-device-samd (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Pristell, C.; Byun, H.; Huffstetler, A.N. Opioid Prescribing Has Significantly Decreased in Primary Care. Am. Fam. Physician. 2024, 110, 572–573. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Ashby, D.; Kerry, S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: Effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapham, G.T.; Lee, A.K.; Caldeiro, R.M.; McCarty, D.; Browne, K.C.; Walker, D.D.; Kivlahan, D.R.; Bradley, K.A. Frequency of Cannabis Use Among Primary Care Patients in Washington State. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2017, 30, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, J.-W.J.; Wilson, D.L.; Nguyen, K.; Gellad, W.F.; Diiulio, J.; Militello, L.; Yan, S.; Harle, C.A.; Nelson, D.; Rosenberg, E.I.; et al. Protocol for a Single-Arm Pilot Clinical Trial: Developing and Evaluating a Machine Learning Opioid Prediction & Risk-Stratification E-Platform (DEMONSTRATE). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238522

Hong J-WJ, Wilson DL, Nguyen K, Gellad WF, Diiulio J, Militello L, Yan S, Harle CA, Nelson D, Rosenberg EI, et al. Protocol for a Single-Arm Pilot Clinical Trial: Developing and Evaluating a Machine Learning Opioid Prediction & Risk-Stratification E-Platform (DEMONSTRATE). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238522

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Je-Won J., Debbie L. Wilson, Khoa Nguyen, Walid F. Gellad, Julie Diiulio, Laura Militello, Shunhua Yan, Christopher A. Harle, Danielle Nelson, Eric I. Rosenberg, and et al. 2025. "Protocol for a Single-Arm Pilot Clinical Trial: Developing and Evaluating a Machine Learning Opioid Prediction & Risk-Stratification E-Platform (DEMONSTRATE)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238522

APA StyleHong, J.-W. J., Wilson, D. L., Nguyen, K., Gellad, W. F., Diiulio, J., Militello, L., Yan, S., Harle, C. A., Nelson, D., Rosenberg, E. I., Schmidt, S., Chang, C.-C. H., Cochran, G., Wu, Y., Staras, S. A. S., Kuza, C., & Lo-Ciganic, W.-H. (2025). Protocol for a Single-Arm Pilot Clinical Trial: Developing and Evaluating a Machine Learning Opioid Prediction & Risk-Stratification E-Platform (DEMONSTRATE). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238522