Feasibility of Trastuzumab-Deruxtecan in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

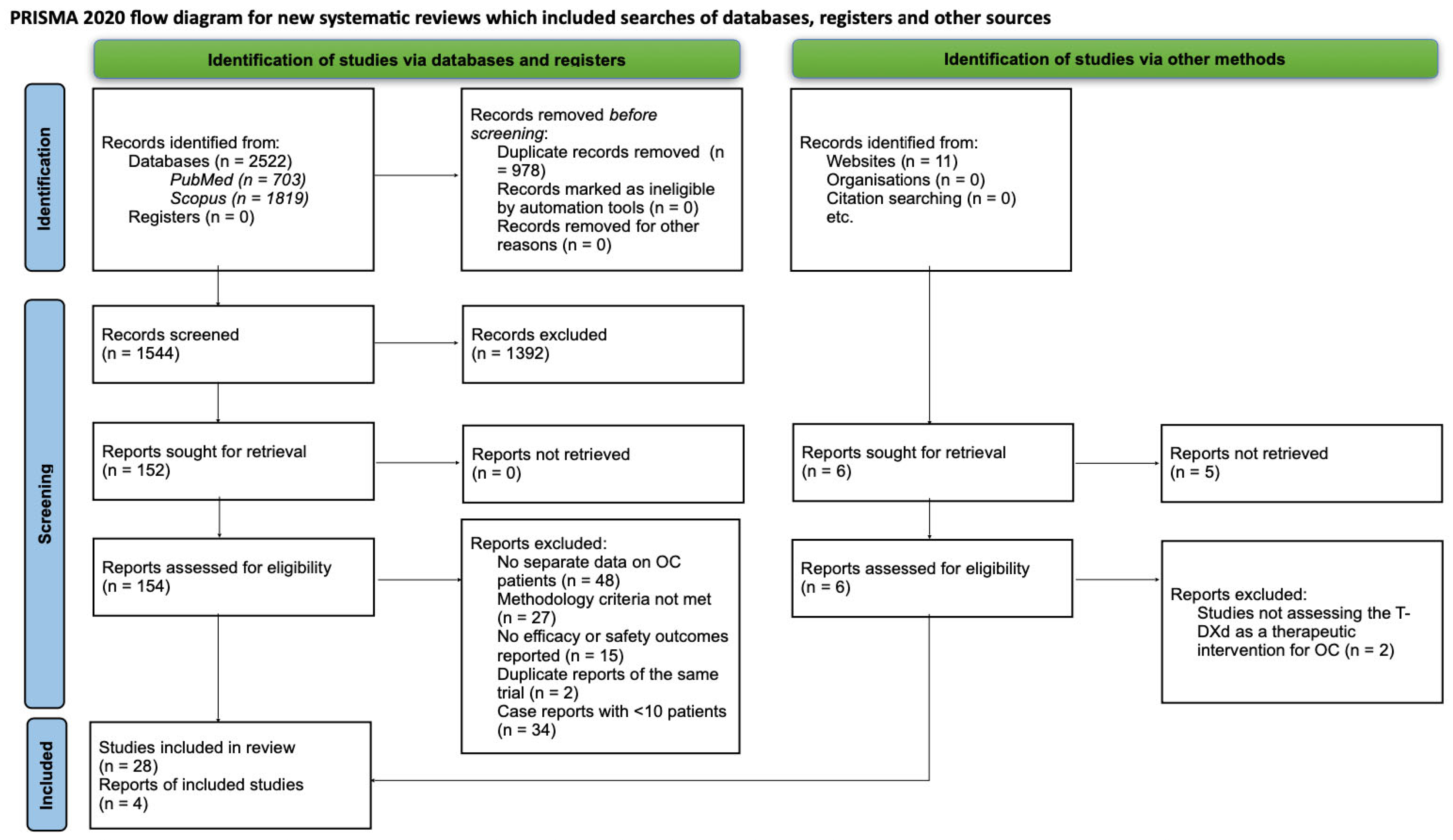

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Method

2.2. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Fundamental Principles of the Pharmaceutical

3.2. Outcomes of Clinical Trials

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | antibody-drug conjugate |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FRα | folate receptor α |

| HER2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| ILD | interstitial lung disease |

| MIRV | mirvetuximab soravtansine-gynx |

| OC | ovarian cancer |

| ORR | objective response rate |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| T-DXd | trastuzumab-deruxtecan |

References

- Cabasag, C.J.; Fagan, P.J.; Ferlay, J.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; Liu, L.; van der Aa, M.A.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Ovarian cancer today and tomorrow: A global assessment by world region and Human Development Index using GLOBOCAN 2020. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideris, M.; Menon, U.; Manchanda, R. Screening and prevention of ovarian cancer. Med. J. Aust. 2024, 220, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann, J.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Amant, F.; Concin, N.; Davidson, B.; Fotopoulou, C.; González-Martin, A.; Gourley, C.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; et al. ESGO–ESMO–ESP consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology and early, advanced and recurrent disease. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Alvarez, R.D.; Backes, F.J.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Barroilhet, L.; Behbakht, K.; Berchuck, A.; Chen, L.-M.; Chitiyo, V.C.; Cristea, M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Ovarian Cancer, Version 3.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Luviano, P.; Medina-Gaona, L.A.; Magaña-Pérez, K. Epidemiology of ovarian cancer. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, P.M.; Jordan, S.J. Global epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanlarkhani, N.; Azizi, E.; Amidi, F.; Khodarahmian, M.; Salehi, E.; Pazhohan, A.; Farhood, B.; Mortezae, K.; Goradel, N.H.; Nashtaei, M.S. Metabolic risk factors of ovarian cancer: A review. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2021, 26, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samuel, D.; Diaz-Barbe, A.; Pinto, A.; Schlumbrecht, M.; George, S. Hereditary Ovarian Carcinoma: Cancer Pathogenesis Looking beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cells 2022, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferris, J.S.; Morgan, D.A.; Tseng, A.S.; Terry, M.B.; Ottman, R.; Hur, C.; Wright, J.D.; Genkinger, J.M. Risk factors for developing both primary breast and primary ovarian cancer: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 190, 104081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, M.E.; Farland, L.V.; Yan, B.; Wang, J.; Trabert, B.; Doherty, J.A.; Meeks, H.D.; Madsen, M.; Guinto, E.; Collin, L.J.; et al. Endometriosis Typology and Ovarian Cancer Risk. JAMA 2024, 332, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kuroki, L.; Guntupalli, S.R. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. BMJ 2020, 371, m3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Xia, B.-R.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Lou, G.; Jin, W.-L. Immunotherapy for Ovarian Cancer: Adjuvant, Combination, and Neoadjuvant. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 577869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fuentes-Antrás, J.; Genta, S.; Vijenthira, A.; Siu, L.L. Antibody–drug conjugates: In search of partners of choice. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpel, H.C.; Powell, S.S.; Pothuri, B. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Gynecologic Cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2023, 43, e390772, Erratum in Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2023, 43, e390772CX1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Makker, V.; Oaknin, A.; Oh, D.-Y.; Banerjee, S.; González-Martín, A.; Jung, K.H.; Ługowska, I.; Manso, L.; Manzano, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Expressing Solid Tumors: Primary Results From the DESTINY-PanTumor02 Phase II Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mauricio, D.; Bellone, S.; Mutlu, L.; McNamara, B.; Manavella, D.D.; Demirkiran, C.; Verzosa, M.S.Z.; Buza, N.; Hui, P.; Hartwich, T.M.P.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201a), a HER2-targeting antibody–drug conjugate with topoisomerase I inhibitor payload, shows antitumor activity in uterine and ovarian carcinosarcoma with HER2/neu expression. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 170, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keam, S.J. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biopharma PEG. PEG Supplier. Available online: https://www.biochempeg.com/article/291.html (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Yin, O.; Xiong, Y.; Endo, S.; Yoshihara, K.; Garimella, T.; AbuTarif, M.; Wada, R.; LaCreta, F. Population Pharmacokinetics of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Positive Breast Cancer and Other Solid Tumors. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 109, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information About Approved Drugs. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-fam-trastuzumab-deruxtecan-nxki-unresectable-or-metastatic-her2 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Henning, J.-W.; Brezden-Masley, C.; Gelmon, K.; Chia, S.; Shapera, S.; McInnis, M.; Rayson, D.; Asselah, J. Managing the Risk of Lung Toxicity with Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (T-DXd): A Canadian Perspective. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8019–8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Soares, L.; Vilbert, M.; Rosa, V.; Oliveira, J.; Deus, M.; Freitas-Junior, R. Incidence of interstitial lung disease and cardiotoxicity with trastuzumab deruxtecan in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dempsey, N.; Rosenthal, A.; Dabas, N.; Kropotova, Y.; Lippman, M.; Bishopric, N.H. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: A review of clinical risk factors, pharmacologic prevention, and cardiotoxicity of other HER2-directed therapies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 188, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.N.; Angelergues, A.; Konecny, G.E.; García, Y.; Banerjee, S.; Lorusso, D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Moroney, J.W.; Colombo, N.; Roszak, A.; et al. Mirvetuximab Soravtansine in FRα-Positive, Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2162–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Lorusso, D.; Oaknin, A.; Pignata, S.; Dean, A.; Denys, H.; Colombo, N.; Van Gorp, T.; Konner, J.A.; Marin, M.R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer With High Folate Receptor Alpha Expression: Results From the SORAYA Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2436–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gilbert, L.; Oaknin, A.; Matulonis, U.A.; Mantia-Smaldone, G.M.; Lim, P.C.; Castro, C.M.; Provencher, D.; Memarzadeh, S.; Method, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Safety and efficacy of mirvetuximab soravtansine, a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), in combination with bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 170, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogani, G.; Coleman, R.L.; Vergote, I.; van Gorp, T.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Oaknin, A.; Matulonis, U.; O’mAlley, D.; Raspagliesi, F.; Scambia, G.; et al. Mirvetuximab soravtansine-gynx: First antibody/antigen-drug conjugate (ADC) in advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 34, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oaknin, A.; Lee, J.-Y.; Makker, V.; Oh, D.-Y.; Banerjee, S.; González-Martín, A.; Jung, K.H.; Ługowska, I.; Manso, L.; Manzano, A.; et al. Efficacy of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in HER2-Expressing Solid Tumors by Enrollment HER2 IHC Status: Post Hoc Analysis of DESTINY-PanTumor02. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 4125–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhu, H. Mirvetuximab soravtansine in platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer with high folate receptor-alpha expression: A cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 35, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mudumba, R.; Chan, H.-H.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Correia, L.; Ballreich, J.; Levy, J. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan Versus Trastuzumab Emtansine for Patients With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer in the United States. Value Health 2023, 27, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Trials gov. International Registry of Clinical Trials. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06271837?rank=12024 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Clinical Trials gov. International Registry of Clinical Trials. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06819007?cond=Ovarian%20Cancer&term=Trastuzumab&rank=22025 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | T-DXd | MIRV |

|---|---|---|

| target | HER2 (including HER2-low and HER2-mutant cases) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] | FRα [24,25,26,27] |

| FDA approval for OC | not yet (in trials for HER2-positive OC) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] | approved for FRα-positive, platinum-resistant OC in 2022 [24,25,26,27] |

| payload | deruxtecan: a topoisomerase I inhibitor disrupting DNA replication [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] | DM4: a maytansine derivative disrupting microtubule dynamics [24,25,26,27] |

| most severe adverse effects | pulmonary toxicity (including pneumonia, pulmonary fibrosis, ILD or lung injury syndrome), cardiac damage [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] | blurred vision [24,25,26,27] |

| trial examples | DESTINY-PanTumor02 [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] | SORAYA and MIRASOL [24,25,26,27] |

| Characteristics | DESTINY-PanTumor02 | SORAYA | MIRASOL |

|---|---|---|---|

| aim of the study | effectiveness of T-DXd among adults with HER-2 expressing locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic tumors with documented progression despite previous treatments or without alternative treatments [15,28] | first to test the efficacy and safety of MIRV in adults with platinum-resistant OC [25,27] | evaluate effectiveness and safety of treating platinum-resistant, high-grade serous OC among adults with high FRα expression tumors, with MIRV in comparison to chemotherapy [26,27] |

| phase of the trial | II [15,28] | II [24,25,27] | III [24,26,27] |

| dosage of the drug | 5.4 mg/kg given as an intravenous infusion once every 3 weeks [15,28] | 6 mg/kg given as an intravenous infusion once every 3 weeks [24,25,27] | 6 mg/kg given as an intravenous infusion once every 3 weeks [24,26,27] |

| number of participants | 40 [15,28] | 105 [24,25,27] | 453 (227 in MIRV group, 226 chemotherapy group) [24,26,27] |

| ORR | 42.5% [15,28] | 32.4% [24,25,27] | 42.3% in MIRV group (vs. 15.9% in chemotherapy group) [24,26,27] |

| median overall survival | 20.0 months [15,28] | 15.0 months [24,25,27] | 16.46 months in MIRV group (vs. 12.75 months in chemotherapy group) [24,26,27] |

| most common adverse effects | nausea, anemia, fatigue, decreased appetite, diarrhea [15,28] | blurred vision, nausea, keratopathy [24,25,27] | blurred vision, keratopathy, abdominal pain, fatigue [24,26,27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orzelska, J.; Trzcińska, A.; Gierulska, N.; Lachowska, K.; Mazur, K.; Tarkowski, R.; Puzio, I.; Tomaszewska, E.; Kułak, A.; Kułak, K. Feasibility of Trastuzumab-Deruxtecan in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238483

Orzelska J, Trzcińska A, Gierulska N, Lachowska K, Mazur K, Tarkowski R, Puzio I, Tomaszewska E, Kułak A, Kułak K. Feasibility of Trastuzumab-Deruxtecan in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238483

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrzelska, Julia, Amelia Trzcińska, Natalia Gierulska, Katarzyna Lachowska, Karolina Mazur, Rafał Tarkowski, Iwona Puzio, Ewa Tomaszewska, Anna Kułak, and Krzysztof Kułak. 2025. "Feasibility of Trastuzumab-Deruxtecan in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238483

APA StyleOrzelska, J., Trzcińska, A., Gierulska, N., Lachowska, K., Mazur, K., Tarkowski, R., Puzio, I., Tomaszewska, E., Kułak, A., & Kułak, K. (2025). Feasibility of Trastuzumab-Deruxtecan in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238483