Sputum Microbiome Based on the Etiology and Severity of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

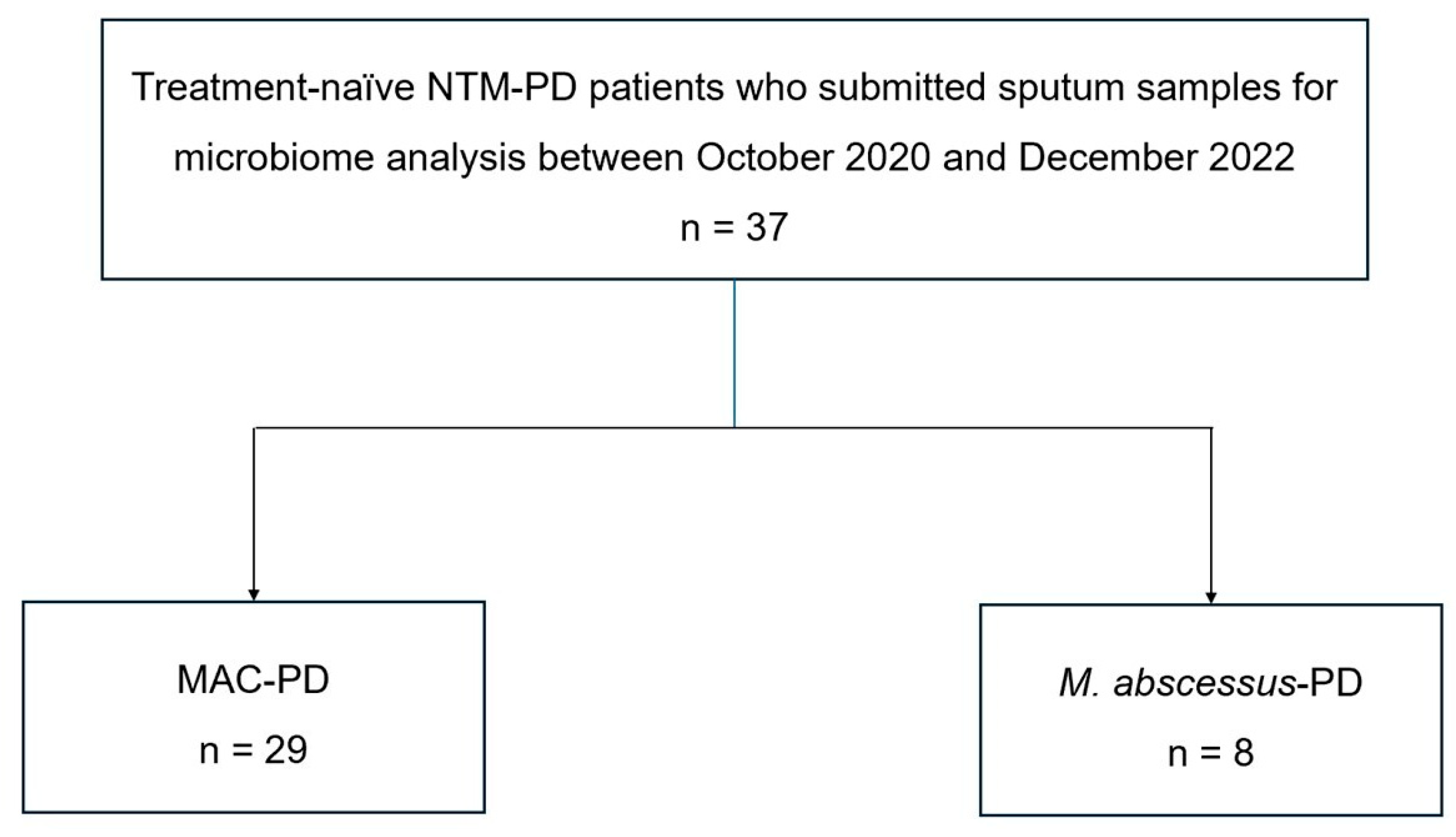

2.1. Study Patients and Data Collection

2.2. Sputum Collection and Sequencing

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Patients

3.2. Differential Sputum Microbiota Between MAC-PD and M. abscessus-PD

3.3. Microbial Metabolic Pathways Associated with Disease Severity of NTM-PD

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prevots, D.R.; Marshall, J.E.; Wagner, D.; Morimoto, K. Global epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: A review. Clin. Chest Med. 2023, 44, 675–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevots, D.R.; Marras, T.K. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: A review. Clin. Chest Med. 2015, 36, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefsloot, W.; van Ingen, J.; Andrejak, C.; Angeby, K.; Bauriaud, R.; Bemer, P.; Beylis, N.; Boeree, M.J.; Cacho, J.; Chihota, V.; et al. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: An NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 42, 1604–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, D. Infection source and epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2019, 82, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.E.; Aksamit, T.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Catanzaro, A.; Daley, C.; Gordin, F.; Holland, S.M.; Horsburgh, R.; Huitt, G.; Iademarco, M.F.; et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 367–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, C.L.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lange, C.; Cambau, E.; Wallace, R.J., Jr.; Andrejak, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Brozek, J.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: An official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2000535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.G.; Jhun, B.W.; Kim, H.; Kwon, O.J. Treatment outcomes of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease according to disease severity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.L.; Lin, C.H.; Lee, M.R.; Huang, W.C.; Sheu, C.C.; Cheng, M.H.; Lu, P.L.; Huang, C.H.; Yeh, Y.T.; Yang, J.M.; et al. Sputum bacterial microbiota signature as a surrogate for predicting disease progression of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 149, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, I.; Wu, B.G.; Li, Y.; Scott, A.S.; Malecha, P.; Scaglione, B.; Wang, J.; Basavaraj, A.; Chung, S.; Bantis, K.; et al. Evaluation of the airway microbiome in nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1800810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kang, N.; Jhun, B.W. Comparison of the sputum microbiome between patients with stable nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease and patients requiring treatment. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philley, J.V.; Kannan, A.; Olusola, P.; McGaha, P.; Singh, K.P.; Samten, B.; Griffith, D.E.; Dasgupta, S. Microbiome diversity in sputum of nontuberculous mycobacteria infected women with a history of breast cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 52, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilloux, C.A.; Lamoureux, C.; Beauruelle, C.; Héry-Arnaud, G. Porphyromonas: A neglected potential key genus in human microbiomes. Anaerobe 2021, 68, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, K.; Zain, N.M.M.; Stewart, I.; Fogarty, A.; Nash, E.F.; Whitehouse, J.L.; Smyth, A.R.; Lilley, A.K.; Knox, A.; Williams, P.; et al. Porphyromonas pasteri and Prevotella nanceiensis in the sputum microbiota are associated with increased decline in lung function in individuals with cystic fibrosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 001481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenboom, I.; Thavarasa, A.; Richardson, H.; Long, M.B.; Wiehlmann, L.; Davenport, C.F.; Shoemark, A.; Chalmers, J.D.; Tümmler, B. Sputum metagenomics of people with bronchiectasis. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 01008-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minias, A.; Gąsior, F.; Brzostek, A.; Jagielski, T.; Dziadek, J. Cobalamin is present in cells of non-tuberculous mycobacteria, but not in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipkorir, T.; Mashabela, G.T.; de Wet, T.J.; Koch, A.; Dawes, S.S.; Wiesner, L.; Mizrahi, V.; Warner, D.F. De novo cobalamin biosynthesis, transport, and assimilation and cobalamin-mediated regulation of methionine biosynthesis in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e00620-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwamino, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Sato, Y.; Tamizu, E.; Asakura, T.; Uno, S.; Mori, M.; Fujiwara, H.; Ishii, M.; Kawabe, H.; et al. Low serum estradiol levels are related to Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danley, J.; Kwait, R.; Peterson, D.D.; Sendecki, J.; Vaughn, B.; Nakisbendi, K.; Sawicki, J.; Lande, L. Normal estrogen, but low dehydroepiandrosterone levels, in women with pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex. A preliminary study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.G.; Kang, N.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.; Kwon, O.J.; Huh, H.J.; Lee, N.Y.; Jhun, B.W. The lung microbiota in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total (n = 37) | MAC (n = 29) | M. abscessus (n = 8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 59 (53–66) | 60 (54–67) | 53 (50–57) | 0.119 |

| Sex, female | 34 (92) | 26 (90) | 8 (100) | >0.999 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21 (20–23) | 22 (20–23) | 21 (21–22) | 0.915 |

| Positive AFB smear | 7 (19) | 4 (14) | 3 (38) | 0.156 |

| Number of lobes involved by bronchiectasis ¶ | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | 0.435 |

| Cavitary lesion on CT | 5 (14) | 4 (14) | 1 (13) | >0.999 |

| Severe group # | 15 (41) | 11 (38) | 4 (50) | 0.690 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choe, J.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, D.H.; Jhun, B.W. Sputum Microbiome Based on the Etiology and Severity of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238482

Choe J, Kim S-Y, Kim DH, Jhun BW. Sputum Microbiome Based on the Etiology and Severity of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238482

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoe, Junsu, Su-Young Kim, Dae Hun Kim, and Byung Woo Jhun. 2025. "Sputum Microbiome Based on the Etiology and Severity of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238482

APA StyleChoe, J., Kim, S.-Y., Kim, D. H., & Jhun, B. W. (2025). Sputum Microbiome Based on the Etiology and Severity of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238482