From Lab to Workplace: Efficacy of Skin Protection Creams Against Hydrophobic Working Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Occupational Skin Protection Creams Against Hydrophobic Working Materials

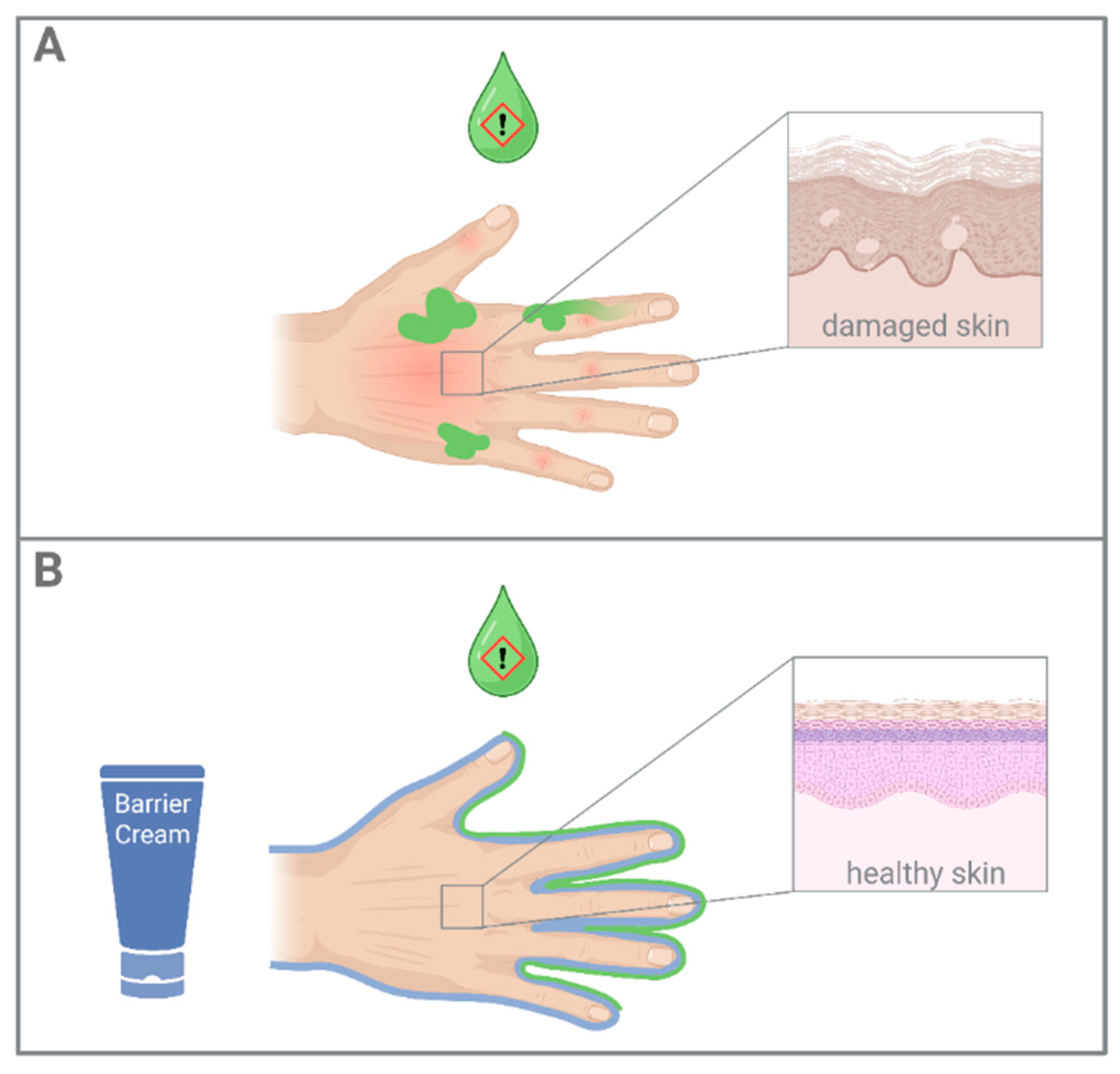

2.1. Barrier Creams

2.2. After-Work Emollients

| Functional Class | Examples (INCI Names) | Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| barrier creams: | |||

| film formers | PERFLUORODECALIN PVP | Create a thin protective, often occlusive or semi-occlusive layer on the skin to prevent moisture loss and shield the skin from environmental stressors. | [10,20,21] |

| absorbers | TALC KAOLIN | Form a dry, powdery layer that helps to prevent oils and other hydrophobic materials from adhering directly to the skin through absorption. | [10,20] |

| astringents | HAMAMELIS VIRGINIA EXTRACT ALUMINUM CHLOROHYDRATE | Contract skin tissue, and reduce perspiration and oil production. May also reduce inflammation. | [10,12,22] |

| chelating agents | DISODIUM EDTA | Bind to metal ions (e.g., calcium, magnesium) to reduce oxidative damage. | [10,23] |

| after-work emollients: | |||

| moisturizers | GLYCERIN UREA | Draw water into the stratum corneum, improving hydration and maintaining skin elasticity. | [22] |

| lipids | CERAMIDES LINOLEIC ACID CHOLESTEROL | Restore skin’s lipid barrier, enhancing hydration, skin flexibility, and protection against environmental damage. | [18] |

3. Efficacy and Clinical Evidence

Challenges Regarding Efficacy Testing

| Test Method | Model Type | Principle | Measurements | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch testing | In vivo (human) | A substance is applied under a patch or chamber to a BC-treated and an untreated site for a defined duration. 24–48 h afterwards, skin irritation is determined. | TEWL, erythema (visual scoring or chromametry), skin blood flow measurements (Laser Doppler), skin hydration measurements (capacitance, conductance or impedance) | Many occupationally relevant hydrophobic substances are prohibited for human testing. Here, toxic concentrations must be avoided but irritation in the control group must be established for meaningful comparisons. While there are guidelines by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD) available for diagnostic patch testing, none exist for the efficacy testing of BCs. | [40,41,42,43,44] |

| Repetitive irritation testing (RIT) | In vivo (human) | The test substance is applied repeatedly over multiple days (often up to two weeks) on BC-treated and untreated skin. The substance may be applied multiple times per day as well. Skin irritation may be assessed daily or at the end of the test phase. | TEWL, erythema (visual scoring or chromametry), skin blood flow measurements (Laser Doppler), skin hydration measurements (capacitance, conductance or impedance) | Many occupationally relevant hydrophobic substances are prohibited for human testing. Here, toxic concentrations must be avoided but irritation in the control group must be established for meaningful comparisons. No standards or guidelines are available. | [12,25] |

| Tape stripping | In vivo (human), ex vivo | A (hydrophobic) dye is applied onto BC-treated and untreated skin of human volunteers or excised human or animal skin. A tape is applied in a standardized manner and removed. This step is repeated with a fresh tape until a few layers of the epidermis are removed. This method investigates the depth of the penetration of the dye as well as the state of the skin. The amount of removed corneocytes correlates with skin health. | The tapes are analyzed for the content of the test substance and/or amount of corneocytes. | Dyes are only a surrogate and may not mimic real occupational substances. This model does not directly assess irritation but rather the depth of dye penetration. The standard dye for hydrophobic substances is Oil Red dissolved in ethanol. Ethanol can act as a penetration enhancer. | [45,46] |

| Perfused Bovine udder model | Ex vivo | The udder is removed after slaughter, and the arterial supply is cannulated and perfused with an appropriate fluid. BCs can be applied on the skin surface before exposure to a test substance. The permeated amount of the substance can be analyzed in the perfusate. | The perfusate is analyzed for concentration of the specific substance that was applied (e.g., with HPLC). | The udder must be obtained shortly after slaughter. Its skin differs from human skin (lipid composition and follicular structure). Uneven perfusion can occur due to partial clotting, vessel collapse, or tissue heterogeneity. No standards or guidelines are available. | [47,48] |

| Franz diffusion cells | In vitro (skin equivalents), ex vivo | A synthetic membrane, artificial skin or excised human or animal skin is clamped between two chambers of a Franz diffusion cell. The chamber underneath the skin is filled with a receptor fluid (e.g., saline) and collects the test substance which is applied on top of the dermis part of the untreated or BC-treated skin or membrane. The test substance must have adequate solubility in the receptor fluid, which is often achieved by adding ethanol or albumin in the case of hydrophobic substances. Guideline available: OECD Test Guideline 428. | The receptor fluid is analyzed for concentration of the specific substance that was applied (e.g., with HPLC). | This model investigates the permeation of substances rather than irritation. Hydrophobic substances may remain in the SC; hence, they might not be detected in the receptor fluid (there are methods available to assess the content that remained in the skin). The skin/membrane will become hyperhydrated due to constant contact with the receptor fluid during the experiment which likely increases its permeability. | [49,50,51,52] |

4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACD | Allergic contact dermatitis |

| BC | Barrier cream |

| CMR | carcinogenic, mutagenic and reprotoxic |

| dOFM | dermal open flow microperfusion |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| ICD | Irritant Contact Dermatitis |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| PFPE | Perfluoropolyether |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| SC | Stratum corneum |

| TEWL | Transepidermal Water Loss |

References

- Bains, S.N.; Nash, P.; Fonacier, L. Irritant Contact Dermatitis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfarth, F.; Schliemann, S.; Antonov, D.; Elsner, P. Dry skin, barrier function, and irritant contact dermatitis in the elderly. Clin. Dermatol. 2011, 29, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepgen, T.L.; Coenraads, P.J. The epidemiology of occupational contact dermatitis. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1999, 72, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodde, B.; Paul, M.; Roguedas-Contios, A.M.; Eniafe-Eveillard, O.B.; Misery, L.; Dewitte, J.D. Occupational dermatitis in workers exposed to detergents, disinfectants, and antiseptics. Skinmed 2012, 10, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, G.; Rasmussen, K.; Bregnhøj, A.; Isaksson, M.; Diepgen, T.L.; Carstensen, O. Causes of irritant contact dermatitis after occupational skin exposure: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkier-Sorensen, L. Occupational skin diseases. Contact Dermat. 1996, 35 (Suppl. 1), 1–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.L. Cutting oil dermatitis on guinea pig skin (I). Cutting oil dermatitis and barrier cream. Contact Dermat. 1991, 24, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fartasch, M.; Diepgen, T.L.; Drexler, H.; Elsner, P.; John, S.M.; Schliemann, S. S1 guideline on occupational skin products: Protective creams, skin cleansers, skin care products (ICD 10: L23, L24)—Short version. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2015, 13, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresken, J.; Klotz, A. Occupational skin-protection products—A review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2003, 76, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.S.; Brown, L.H.; Brancaccio, R.R. Are barrier creams actually effective? Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2001, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliermann, S.; Kleesz, P.; Elsner, P. Protective creams fail to prevent solvent-induced cumulative skin irritation–results of a randomized double-blind study. Contact Dermat. 2013, 69, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, P.J.; Schulze-Dirks, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Axthelm, I. Efficacy of skin barrier creams (II). Ineffectiveness of a popular “skin protector” against various irritants in the repetitive irritation test in the guinea pig. Contact Dermat. 1993, 29, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.; Salameh, B.; Stolkovich, S.; Nikl, M.; Barth, A.; Ponocny, E.; Drexler, H.; Tappeiner, G. Effectiveness of skin protection creams in the prevention of occupational dermatitis: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.L. Occupational contact dermatitis of the upper extremity. Occup. Med. 1994, 9, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schurer, N.Y.; Elias, P.M. The biochemistry and function of stratum corneum lipids. Adv. Lipid Res. 1991, 24, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meguro, S.; Arai, Y.; Masukawa, Y.; Uie, K.; Tokimitsu, I. Relationship between covalently bound ceramides and transepidermal water loss (TEWL). Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2000, 292, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damien, F.; Boncheva, M. The extent of orthorhombic lipid phases in the stratum corneum determines the barrier efficiency of human skin in vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danby, S.G.; Andrew, P.V.; Brown, K.; Chittock, J.; Kay, L.J.; Cork, M.J. An Investigation of the Skin Barrier Restoring Effects of a Cream and Lotion Containing Ceramides in a Multi-vesicular Emulsion in People with Dry, Eczema-Prone, Skin: The RESTORE Study Phase 1. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 10, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluhr, J.W.; Menzel, P.; Schwarzer, R.; Nikolaeva, D.G.; Darlenski, R.; Albrecht, M. Clinical efficacy of a multilamellar cream on skin physiology and microbiome in an epidermal stress model: A controlled double-blinded study. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2024, 46, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, H.D.; Venier, M.; Wu, Y.; Eastman, E.; Urbanik, S.; Diamond, M.L.; Shalin, A.; Schwartz-Narbonne, H.; Bruton, T.A.; Blum, A.; et al. Fluorinated Compounds in North American Cosmetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliemann-Willers, S.; Wigger-Alberti, W.; Elsner, P. Efficacy of a new class of perfluoropolyethers in the prevention of irritant contact dermatitis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2001, 81, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, U.; Wigger-Alberti, W.; Gabard, B.; Elsner, P. Efficacy of a barrier cream and its vehicle as protective measures against occupational irritant contact dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 2000, 42, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valacchi, G. Supplement Individual Article: Chelating Agents in Skincare: Comprehensive Protection Against Environmental Aggressors. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2023, 22, SF383499s5–SF383499s10. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, P.; Musitelli, G.; Perugini, P. Wetting and adhesion evaluation of cosmetic ingredients and products: Correlation of in vitro-in vivo contact angle measurements. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2017, 39, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schluter-Wigger, W.; Elsner, P. Efficacy of 4 commercially available protective creams in the repetitive irritation test (RIT). Contact Dermat. 1996, 34, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, K.; Hilt, B. Skin disorders in ship’s engineers exposed to oils and solvents. Contact Dermat. 1997, 36, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.; Rönsch, H.; Elsner, P.; Dittmar, D.; Bennett, C.; Schuttelaar, M.L.A.; Lukács, J.; John, S.M.; Williams, H.C. Interventions for preventing occupational irritant hand dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, Cd004414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and the Council. Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 342, 59–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, E.; Schwarz, A.; Fink, J.; Kamolz, L.P.; Kotzbeck, P. Modelling the Complexity of Human Skin In Vitro. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardesca, E. EEMCO guidance for the assessment of stratum corneum hydration: Electrical methods. Skin. Res. Technol. 1997, 3, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, V. EEMCO guidance for the assessment of transepidermal water loss in cosmetic sciences. Skin. Pharmacol. Appl. Skin. Physiol. 2001, 14, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardesca, E.; Loden, M.; Serup, J.; Masson, P.; Rodrigues, L.M. The revised EEMCO guidance for the in vivo measurement of water in the skin. Skin. Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardesca, E.; Fideli, D.; Borroni, G.; Rabbiosi, G.; Maibach, H. In vivo hydration and water-retention capacity of stratum corneum in clinically uninvolved skin in atopic and psoriatic patients. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1990, 70, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodén, M. The increase in skin hydration after application of emollients with different amounts of lipids. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1992, 72, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodén, M.; Lindberg, M. The influence of a single application of different moisturizers on the skin capacitance. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1991, 71, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, P.A.; Raney, S.G.; Franz, T.J. Percutaneous absorption in man: In vitro-in vivo correlation. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011, 24, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, M.; Ruzgas, T.; Svedenhag, P.; Anderson, C.D.; Ollmar, S.; Engblom, J.; Björklund, S. Skin hydration dynamics investigated by electrical impedance techniques in vivo and in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECHA. Highlights from September RAC and SEAC Meetings. 2024 ECHA/NR/24/24. Available online: https://www.echa.europa.eu/-/highlights-from-september-2024-rac-and-seac-meetings (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Française République. LOI n° 2025-188 du 27 février 2025. J. Off. République Française 2025. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/download/pdf?id=z1qB8sWbalojVtx8AaeSDvW-c5JqEb-SEAz0MfCl1vU= (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Treffel, P.; Gabard, B. Measurement of sodium lauryl sulfate-induced skin irritation. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1996, 76, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treffel, P.; Gabard, B. Bioengineering measurements of barrier creams efficacy against toluene and NaOH in an in vivo single irritation test. Skin. Res. Technol. 1996, 2, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardesca, E.; Lévêque, J.L.; Masson, P. EEMCO guidance for the measurement of skin microcirculation. Skin. Pharmacol. Appl. Skin. Physiol. 2002, 15, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestmann, E.; Lavrijsen, A.P.; Hermans, J.; Ponec, M. Skin barrier function in healthy volunteers as assessed by transepidermal water loss and vascular response to hexyl nicotinate: Intra- and inter-individual variability. Br. J. Dermatol. 1993, 128, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, J.D.; Aalto-Korte, K.; Agner, T.; Andersen, K.E.; Bircher, A.; Bruze, M.; Cannavó, A.; Gimenez-Arnau, A.; Gonçalo, M.; Goossens, A.; et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing–recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermat. 2015, 73, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Badhe, Y.; Rai, B.; Mitragotri, S. Molecular mechanism of the skin permeation enhancing effect of ethanol: A molecular dynamics study. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12234–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Maibach, H.I. Effect of barrier creams: Human skin in vivo. Contact Dermat. 1996, 35, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, M.; Löscher, W.; Arens, D.; Maass, P.; Lubach, D. The isolated perfused bovine udder as an in vitro model of percutaneous drug absorption. Skin viability and percutaneous absorption of dexamethasone, benzoyl peroxide, and etofenamate. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 1993, 30, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittermann, W.; Kietzmann, M.; Jackwerth, B. The isolated perfused Bovine Udder Skin. ALTEX 1995, 12, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chilcott, R.P.; Jenner, J.; Hotchkiss, S.A.M.; Rice, P. Evaluation of barrier creams against sulphur mustard. I. In vitro studies using human skin. Skin. Pharmacol. Appl. Skin. Physiol. 2002, 15, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casiraghi, A.; Ranzini, F.; Musazzi, U.M.; Franzè, S.; Meloni, M.; Minghetti, P. In vitro method to evaluate the barrier properties of medical devices for cutaneous use. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 90, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Maibach, H.I. Occlusion vs. skin barrier function. Skin. Res. Technol. 2002, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 428: Skin Absorption: In Vitro Method. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. Section 4. 2004. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-428-skin-absorption-in-vitro-method_9789264071087-en.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Birngruber, T.; Tiffner, K.I.; Mautner, S.I.; Sinner, F.M. Dermal open flow microperfusion for PK-based clinical bioequivalence studies of topical drug products. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1061178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenlenz, M.; Aigner, B.; Dragatin, C.; Liebenberger, L.; Zahiragic, S.; Höfferer, C.; Birngruber, T.; Priedl, J.; Feichtner, F.; Schaupp, L.; et al. Clinical applicability of dOFM devices for dermal sampling. Skin. Res. Technol. 2013, 19, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryzalowska, Z.; Blicharz, L.; Michalczyk, A.; Koscian, J.; Maj, M.; Czuwara, J.; Rudnicka, L. The Usefulness of Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography in Monitoring Epidermal Changes in Atopic Dermatitis in Response to Treatment: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunter, D.; Klang, V.; Kocsis, D.; Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Berkó, S.; Erdó, F. Novel aspects of Raman spectroscopy in skin research. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 1311–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadali, M.; Ghiaseddin, A.; Irani, S.; Amirkhani, M.A.; Dahmardehei, M. Design and evaluation of a skin-on-a-chip pumpless microfluidic device. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.U. In Vitro Models Mimicking Immune Response in the Skin. Yonsei Med. J. 2021, 62, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 439: In Vitro Skin Irritation: Reconstructed Human Epidermis Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-439-in-vitro-skin-irritation-reconstructed-human-epidermis-test-method_9789264242845-en.html (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Akagi, T.; Nagura, M.; Hiura, A.; Kojima, H.; Akashi, M. Construction of Three-Dimensional Dermo-Epidermal Skin Equivalents Using Cell Coating Technology and Their Utilization as Alternative Skin for Permeation Studies and Skin Irritation Tests. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer-Korting, M.; Bock, U.; Diembeck, W.; Düsing, H.J.; Gamer, A.; Haltner-Ukomadu, E.; Hoffmann, C.; Kaca, M.; Kamp, H.; Kersen, S.; et al. The use of reconstructed human epidermis for skin absorption testing: Results of the validation study. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2008, 36, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenlenz, M.; Tiffner, K.I.; Raml, R.; Augustin, T.; Dragatin, C.; Birngruber, T.; Schimek, S.; Schwagerle, G.; Pieber, T.R.; Raney, S.G.; et al. Open Flow Microperfusion as a Dermal Pharmacokinetic Approach to Evaluate Topical Bioequivalence. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2017, 56, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Pendlington, R.; Glavin, S.; Chen, T.; Belsey, N.A. Characterisation of skin penetration pathways using stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 204, 114518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.; Namjoshi, S.; Mohammed, Y.; Grice, J.E.; Benson, H.A.E.; Raney, A.G.; Roberts, M.S.; Windbergs, M. Application of Confocal Raman Microscopy for the Characterization of Topical Semisolid Formulations and their Penetration into Human Skin Ex Vivo. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzì, A.E.; Lacarrubba, F.; Musumeci, M.L.; Caltabiano, R.; Micali, G. Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging of Psoriasis with Histopathology Correlation. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2025, 52, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnier, F.; Pedrazzani, M.; Fischman, S.; Viel, T.; Lavoix, A.; Pegoud, D.; Nili, M.; Jimenez, Y.; Ralambondrainy, S.; Cauchard, J.H.; et al. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography coupled with artificial intelligence algorithms to identify quantitative biomarkers of facial skin ageing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.F.E.; Di Cio, A.; Connelly, J.T.; Gautrot, J.E. Design of an Integrated Microvascularized Human Skin-on-a-Chip Tissue Equivalent Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 915702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Sito, L.; Mao, M.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhao, X. Current advances in skin-on-a-chip models for drug testing. Microphysiological Syst. 2018, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Test Method | Model Type | Principle | Measurements | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstructed human epidermis (RHE) testing | In vitro (skin equivalents) | This method is based on lab-grown 3D keratinocyte cultures that form layers similar to a physiological epidermis. BCs can be applied before exposure to a test substance. Toxic substances that are prohibited for use in human testing can be applied in this model. No guidelines are available; however, the OECD Test Guideline 439 could be adapted to include BCs. | The converted blue formazan can be measured photometrically. Values below or equal to 50% indicate a decreased cell viability and with that, irritation. Additionally, cytokine release can be assessed as well. | This is a static model; there is a lack of appendages and immune components in the artificial epidermis. | [36,61] |

| Dermal open flow microperfusion (dOFM) | In vivo (human), in vitro (skin equivalents), ex vivo | Fine tubes are inserted into the dermis and connected to a peristaltic pump for perfusion. The tubes contain an open area, which allows the entry of various molecules (e.g., hydrophilic, hydrophobic, small and large molecules, cytokines, immune cells, etc.). By slowly perfusing the tubes, these molecules are transported away and collected for subsequent analysis. The system is recognized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a validated method for assessing bioequivalence of topical drug products. | The perfusate is analyzed with appropriated methods (e.g., immunoassays, HPLC, etc.). | The method is technically demanding and requires specialized equipment and specifically trained personnel. No standards or guidelines are available. | [53,54,62] |

| Confocal Raman Microscopy | In vivo (human), in vitro (skin equivalents), ex vivo | The specific Raman spectrum of a molecule of interest is detected by a Raman microscope directly in the skin or skin equivalent. This noninvasive method can determine the penetration depth and intensity of a molecule as well as changes in the water content and lipid order of the skin, thereby also assessing skin health simultaneously. Additionally, this method can also inform about the distribution of the compound in the skin, e.g., detecting high signal intensities around hair follicles or sweat ducts suggests follicular uptake. | Characteristic Raman spectral bands are used to detect and quantify molecules. | The detection is limited to the upper epidermis (up to 30 µm); deeper layers of the skin are not reached. The spectral bands of applied BCs could overlap with the skin or with hydrophobic test substances. The method is technically demanding and requires specialized equipment and specifically trained personnel. No standards or guidelines are available. | [63,64] |

| Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography | In vivo (human), in vitro (skin equivalents), ex vivo | Here, a line-shaped beam is simultaneously illuminated and detected, enabling real-time acquisition of cross-sectional and horizontal-section images of the skin. This can be utilized to measure the penetration depth of a topically applied compound as well as assess skin health. | Differences in optical backscattering between tissue structures are determined. | This method cannot assess skin health or irritation. Penetration depth is limited to 500 µm, restricting the visualization to the epidermis and upper dermis. The contrast relies on refractive-index differences, so highly reflective surface films or oily residues can cause optical artifacts. The method is technically demanding and requires specialized equipment and specifically trained personnel. No standards or guidelines are available. | [65,66] |

| Skin-on-a-chip model | In vitro (skin equivalents) | These microfluidic platforms integrate skin equivalents with sensors and a perusable microsystem to allow monitoring as well as continuous sampling. | The perfusate is analyzed with appropriated methods (e.g., immunoassays, HPLC, etc.). Sensors may be integrated to monitor specific parameters during testing. | Fabrication of microfluidic chips is highly complex and the inter-laboratory reproducibility is low because of custom designs and lack of standardization. Further, artificial skin lacks appendages and immune components. No standards or guidelines are available. | [67,68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dick, A.; Metzger, M.; Dungel, P. From Lab to Workplace: Efficacy of Skin Protection Creams Against Hydrophobic Working Materials. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238470

Dick A, Metzger M, Dungel P. From Lab to Workplace: Efficacy of Skin Protection Creams Against Hydrophobic Working Materials. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238470

Chicago/Turabian StyleDick, Anja, Magdalena Metzger, and Peter Dungel. 2025. "From Lab to Workplace: Efficacy of Skin Protection Creams Against Hydrophobic Working Materials" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238470

APA StyleDick, A., Metzger, M., & Dungel, P. (2025). From Lab to Workplace: Efficacy of Skin Protection Creams Against Hydrophobic Working Materials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238470