Assessment of the Connection Between Maxillary Sinus Volume, Number of Surgical Interventions, and Craniofacial Development in Patients with Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection

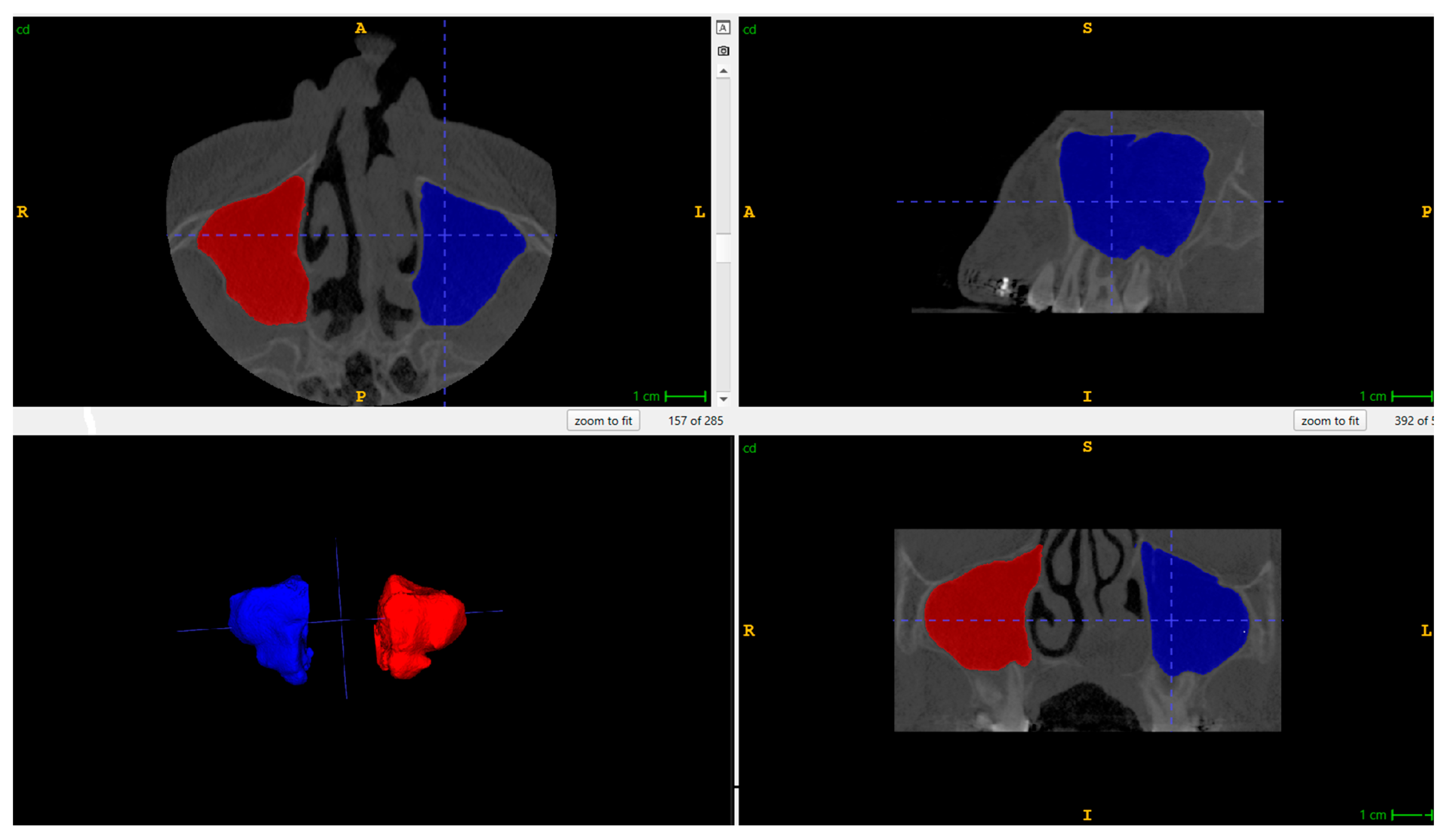

2.4. Radiographic Data Acquisition

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Platform on Rare Disease Registration. Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Mossey, P.A.; Little, J.; Munger, R.G.; Dixon, M.J.; Shaw, W.C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 2009, 374, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, B.; Wang, R.G.; Hawke, M.; Kwok, P. The embryonic development of the lateral nasal wall from 8 to 24 weeks. Laryngoscope 1991, 101, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, W.; Patel, Z.M.; Lin, F.Y. The development and pathologic processes that influence maxillary sinus pneumatization. Anat. Rec. 2008, 291, 1554–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, A.; Boeddinghaus, R. The maxillary sinus: Physiology, development and imaging anatomy. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2019, 48, 20190205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.E.; Zerlin, G.K.; Passy, V. Maxillary sinus development in patients with cleft palates as compared to those with normal palates. Laryngoscope 1982, 92, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Furukawa, M. Maxillary sinus development and sinusitis in patients with cleft lip and palate. Auris Nasus Larynx 2000, 27, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards of Care. ERN CRANIO Website. Available online: https://www.ern-cranio.eu/standards-of-care (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Wlodarczyk, J.R.; Munabi, N.C.O.; Wolfswinkel, E.; Nagengast, E.; Higuch, E.C.; Turk, M.; Urata, M.M.; Hammoudeh, J.A.; Yao, C.; Magee, W., 3rd. Midface Growth Potential in Unoperated Clefts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celie, K.-B.; Wlodarczyk, J.; Naidu, P.; Tapia, M.F.; Nagengast, E.; Yao, C.; Magee, W. Sagittal Growth Restriction of the Midface Following Isolated Cleft Lip Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2024, 61, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waitzman, A.A.; Posnick, J.C.; Armstrong, D.C.; Pron, G.E. Craniofacial skeletal measurements based on computed tomography: Part I. Accuracy and reproducibility. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 1992, 29, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Hamimi, M.; Choi, J.J.E.; Figueredo, C.M.S.; Cameron, M.A. Comparisons of AI automated segmentation techniques to manual segmentation techniques of the maxilla and maxillary sinus for CT or CBCT scans-A Systematic review. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2025, 54, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastav, S.; Tewari, N.; Duggal, R.; Goel, S.; Rahul, M.; Mathur, V.P.; Yadav, R.; Upadhyaya, A.D. Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Assessment of Maxillary Sinus Characteristics in Patients with Cleft Lip and Palate: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2023, 60, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Rezende Barbosa, G.; Pimenta, L.A.; Pretti, H.; Golden, B.A.; Roberts, J.; Drake, A.F. Difference in maxillary sinus volumes of patients with cleft lip and palate. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 2234–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.L.; Francisco, I.; Caramelo, F.; Figueiredo, J.P.; Vale, F. A retrospective and tridimensional study of the maxillary sinus in patients with cleft lip and palate. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2021, 159, e17–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13 (Suppl. S1), S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Kalabalik, F.; Dane, A.; Aktan, A.M.; Ciftci, E.; Tarim, E. Does Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Affect the Maxillary Sinus Volume? Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2018, 55, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikosaka, M.; Nagasao, T.; Ogata, H.; Kaneko, T.; Kishi, K. Evaluation of maxillary sinus volume in cleft alveolus patients using 3-dimensional computed tomography. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2013, 24, e23–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, B.; Shrestha, R.; Lin, T.; Lu, Y.; Lu, H.; Mai, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Ai, H. Evaluation of maxillary sinus volume in different craniofacial patterns: A CBCT study. Oral Radiol. 2021, 37, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinç, K.; İçöz, D. Maxillary sinus volume changes in individuals with different craniofacial skeletal patterns: CBCT study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruç, K.; Akkurt, A.; Tuncer, M.C. Relation between orthodontic malocclusion and maxillary sinus volume. Folia Morphol. 2025, 84, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Yin, N.; Zheng, Y.; Song, T. Characteristics of Maxillary Morphology in Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Patients Compared to Normal Subjects and Skeletal Class III Patients. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, e517–e523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, Z.; Ma, L.; Li, W. Cone-beam computed tomography-synthesized cephalometric study of operated unilateral cleft lip and palate and noncleft children with Class III skeletal relationship. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 150, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamata, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Ogata, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Ishii, T.; Kishi, K. Influence of Lip Revision Surgery on Facial Growth in Patients with A Cleft Lip. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2023, 34, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, P.; Verma, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar Verma, R.; Pal Singh, S. Effects of Secondary Alveolar Bone Grafting on Maxillary Growth in Cleft Lip or Palate Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2024, 61, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Right UCLP | Left UCLP | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2 | 12 | 0.78 |

| Male | 4 | 12 | 0.78 |

| Age | 15.8 (10.3–21.3) | 12.8 (11.3–14.2) | 0.12 |

| RMSV [mm3] | 13,937.0 (8367.5–19,506.5) | 11,816.2 (9789.0–13,843.5) | 0.35 |

| LMSV [mm3] | 12,292.0 (7909.8–16,674.2) | 12,045.0 (10,290.3–13,799.7) | 0.89 |

| No. of Primary Interventions | 1 | 2 | 3 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 5 | 23 | 2 | |

| RMSV [mm3] | 10,422.8 (6280.8–14,564.8) | 12,589.8 (10,361.4–14,818.2) | 13,850.0 (53,696.184–81,396.2) | 0.58 |

| LMSV [mm3] | 10,041.7 (6316.5–13,766.8) | 12,638.0 (10,753.4–14,522.6) | 12,273.0 (16,722.559–41,268.6) | 0.40 |

| No. of Secondary Interventions | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | 7 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| RMSV | 12,802.2 (10,079.9–15,524.5) | 10,839.0 (6596.9–15,081.1) | 11,635.0 (5260.8–18,009.2) | 5925.0 | 16,040.0 | 19,166.0 | 0.42 |

| LMSV | 12,758.2 (10,145.4–15,371.0) | 11,079.7 (8920.1–13,239.4) | 11,732.2 (6434.2–17,030.2) | 5825.0 | 14,860.0 | 14,555.0 | 0.58 |

| No. of Primary Interventions | 1 | 2 | 3 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (81.00 ± 3.00) | 75.3 (73.8–76.7) | 76.6 (75.1–78.2) | 74.5 (67.5–81.6) | 0.58 |

| SNB (78.00 ± 3.00) | 72.6 (71.4–73.9) | 75.9 (74.9–77.0) | 74.0 (73.2–74.8) | 0.005 * |

| ANB (3.00 ± 2.00) | 1.8 (0.394–3.2) | 0.646 (−0.296–1.6) | 3.4 (2.4–4.4) | 0.034 * |

| WITS (0.00 ± 2.00) | −0.523 (−2.849–1.8) | −1.358 (−2.562–−0.155) | 1.8 (−2.15–5.8) | 0.245 |

| SN/NL (8.00 ± 3.00) | 14.0 (10.4–17.6) | 10.6 (9.5–11.8) | 10.2 (7.2–13.1) | 0.12 |

| No. of Secondary Interventions | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (81.00 ± 3.00) | 76.2 (74.4–78.0) | 75.5 (73.5–77.4) | 77.3 (75.9–78.7) | 86.8 | 70.9 | 70.7 | 0.03 * |

| SNB (78.00 ± 3.00) | 75.0 (73.6–76.4) | 75.6 (73.7–77.5) | 75.0 (73.8–76.2) | 79.7 | 71.5 | 73.5 | 0.16 |

| ANB (3.00 ± 2.00) | 0.78 (−0.273–1.8) | −0.106 (−1.79–1.6) | 2.3 (0.76–3.8) | 7.1 | −0.56 | 2.9 | 0.03 * |

| WITS (0.00 ± 2.00) | −1.456 (−2.93–0.02) | −1.457 (−3.64–0.72) | 0.726 (−1.90–3.4) | 4.1 | −4.78 | −0.3 | 0.11 |

| SN/NL (8.00 ± 3.00) | 12.2 (10.4–13.9) | 10.2 (8.7–11.7) | 11.4 (7.7–15.1) | 5.7 | 13.4 | 8.6 | 0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kołodziejska, A.; Nazar, W.; Kalinowska, J.; Racka-Pilszak, B.; Wojtaszek-Słomińska, A. Assessment of the Connection Between Maxillary Sinus Volume, Number of Surgical Interventions, and Craniofacial Development in Patients with Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238468

Kołodziejska A, Nazar W, Kalinowska J, Racka-Pilszak B, Wojtaszek-Słomińska A. Assessment of the Connection Between Maxillary Sinus Volume, Number of Surgical Interventions, and Craniofacial Development in Patients with Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238468

Chicago/Turabian StyleKołodziejska, Aleksandra, Wojciech Nazar, Jolanta Kalinowska, Bogna Racka-Pilszak, and Anna Wojtaszek-Słomińska. 2025. "Assessment of the Connection Between Maxillary Sinus Volume, Number of Surgical Interventions, and Craniofacial Development in Patients with Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238468

APA StyleKołodziejska, A., Nazar, W., Kalinowska, J., Racka-Pilszak, B., & Wojtaszek-Słomińska, A. (2025). Assessment of the Connection Between Maxillary Sinus Volume, Number of Surgical Interventions, and Craniofacial Development in Patients with Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238468