CaNO and eCO Might Be Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Disease Severity and Exacerbations in Interstitial Lung Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

2.2. Exhaled Gas Measurement

2.3. High-Resolution Chest CT Examination

2.4. Pulmonary Function Test

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Population

3.2. FeNO50 Is Significant High in IPF Patients

3.3. Association of Exhaled Gas Levels with Pulmonary Function

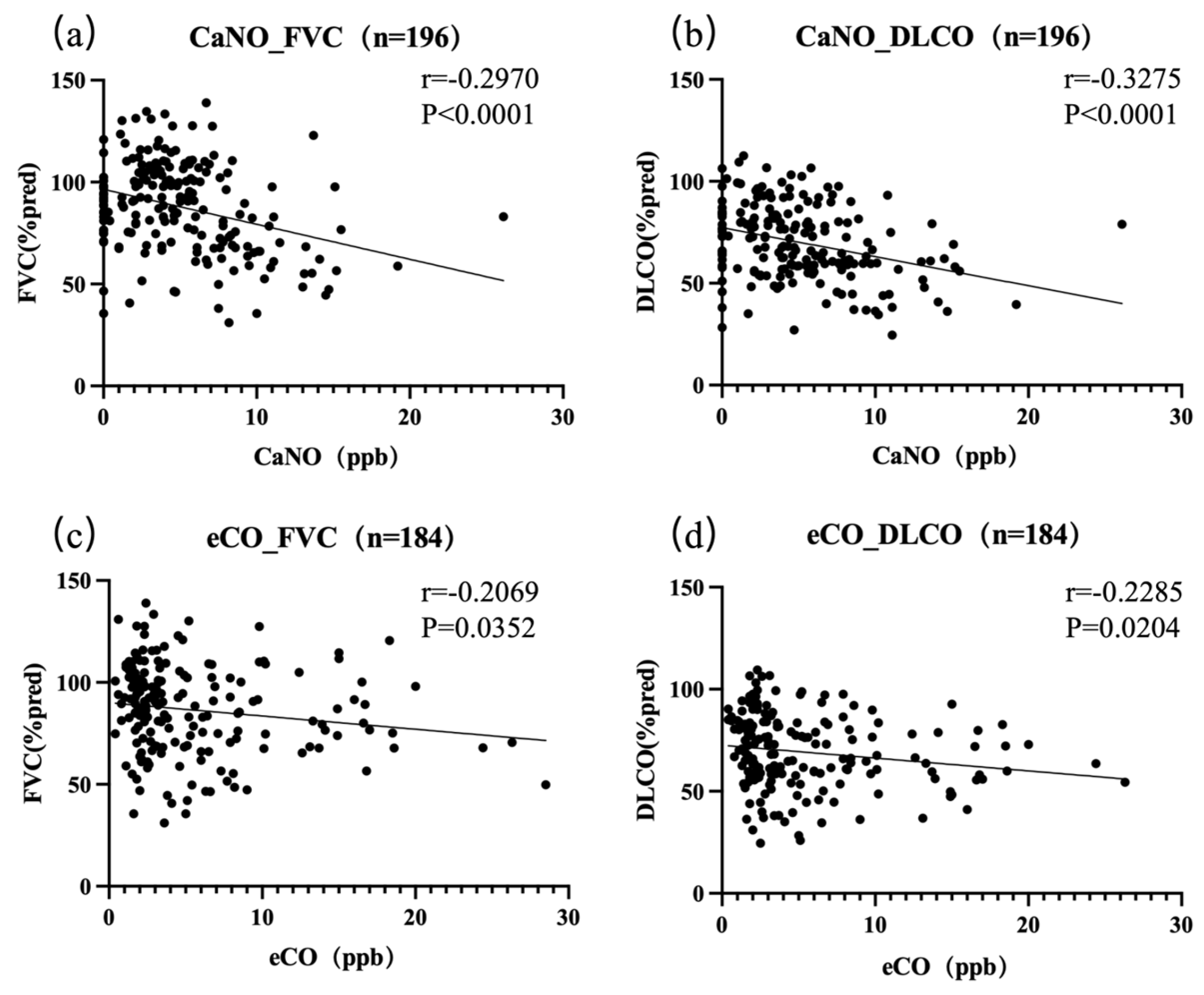

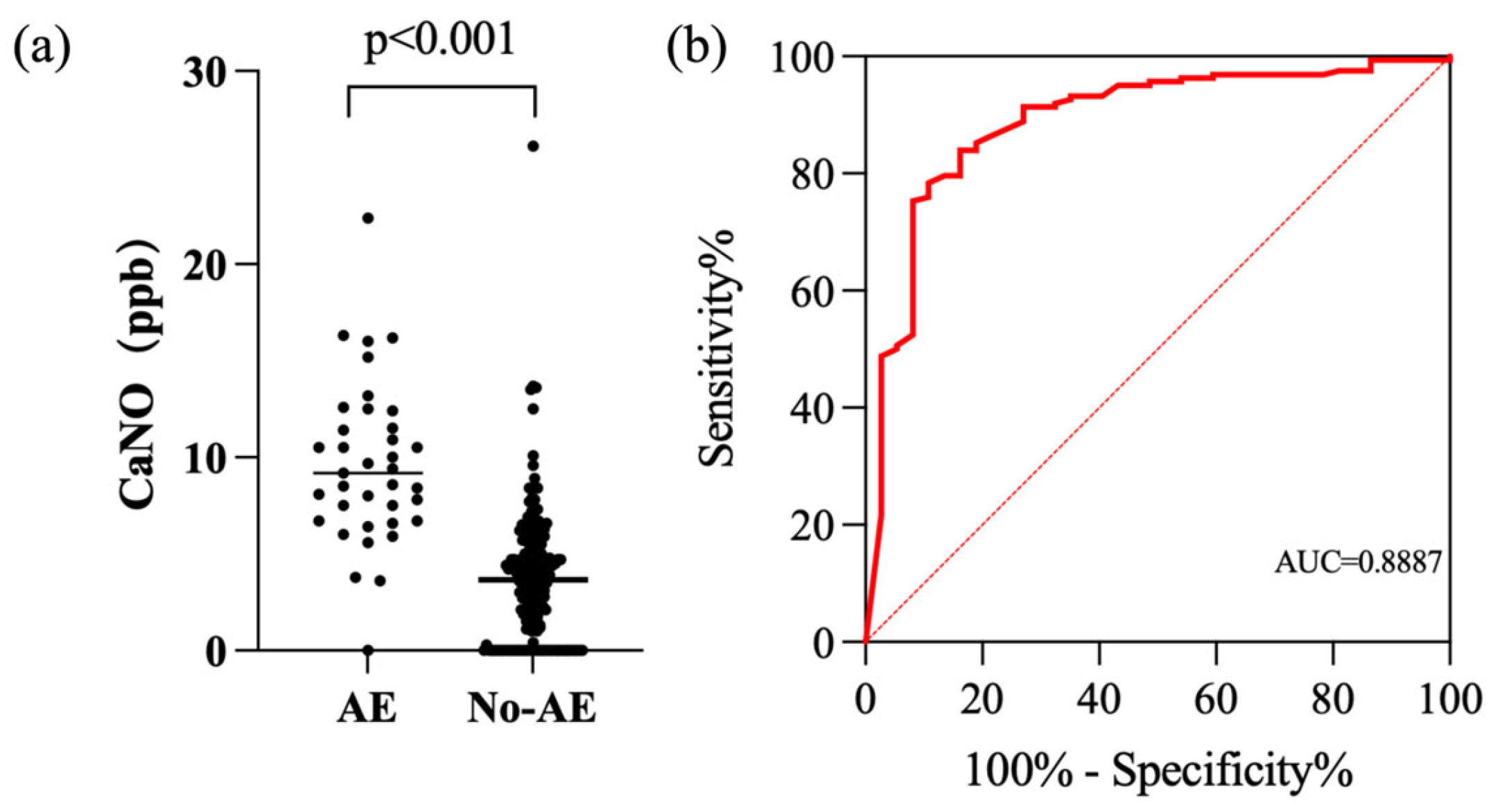

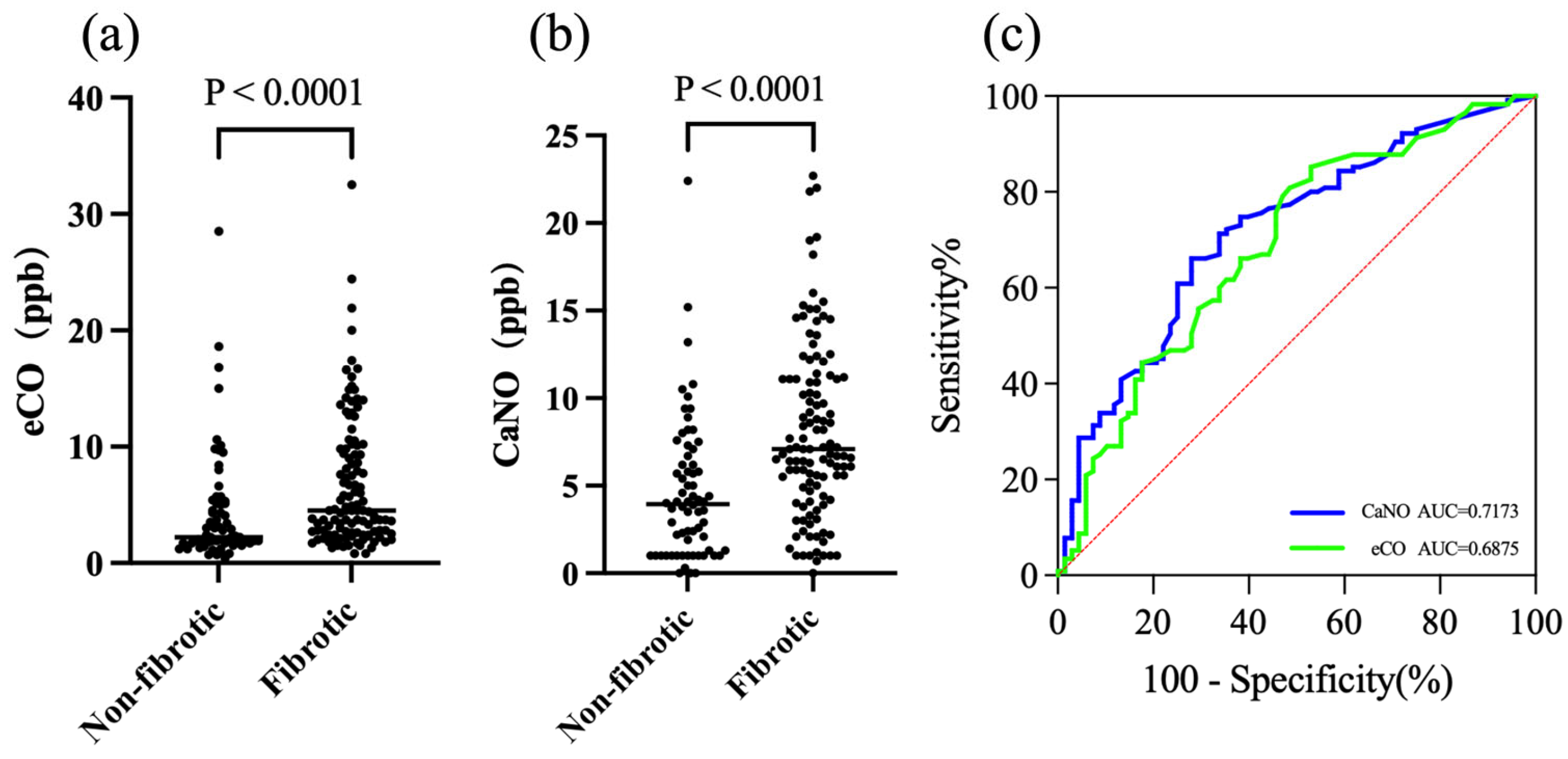

3.4. Exhaled Biomarkers as Indicators of Fibrotic ILD and Acute Exacerbation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | acute exacerbation |

| AE-ILD | acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| AUC | area under the (ROC) curve |

| CI | confidence interval |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CTD-ILD | connective tissue disease-associated ILD |

| DLCO | diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide |

| eCO | exhaled carbon monoxide |

| FeNO | fractional exhaled nitric oxide |

| FeNO50 | FeNO at 50 mL/s |

| FeNO200 | FeNO at 200 mL/s |

| FEV1 | forced expiratory volume in 1 s |

| FVC | forced vital capacity |

| GGO (s) | ground-glass opacity (ies) |

| HC | healthy controls |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| HRCT | high-resolution computed tomography |

| HP | hypersensitivity pneumonitis |

| IIP | idiopathic interstitial pneumonias |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| ILD | interstitial lung disease |

| IPAF | interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features |

| IPF | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| M2 | M2 macrophages |

| MCTD-ILD | mixed connective tissue disease-associated ILD |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| PM/DM-ILD | polymyositis/dermatomyositis-associated ILD |

| RA-ILD | rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| RR | relative risk |

| RV | residual volume |

| SLE-ILD | systemic lupus erythematosus–associated ILD |

| SS-ILD | Sjögren’s syndrome-associated ILD |

| SSc-ILD | systemic sclerosis-associated ILD |

| TLC | total lung capacity |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| %pred | percent predicted |

References

- Zhou, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhu, X. Global, regional, and national burden of interstitial lung diseases and pulmonary sarcoidosis from 2000 to 2021: A systematic analysis of incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1578480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lv, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Ren, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Assessing the global burden of interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis using multiple statistical models: Analysis and future projections. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Guler, S.A.; Chaudhuri, N.; Udwadia, Z.; Sesé, L.; Kaul, B.; Enghelmayer, J.I.; Valenzuela, C.; Malhotra, A.; Ryerson, C.J.; et al. Global epidemiology and burden of interstitial lung disease. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Wang, L.; Xia, S.; Mao, M.; Qian, W.; Peng, X.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, R.; Han, Q.; Luo, Q. The interstitial lung disease spectrum under a uniform diagnostic algorithm: A retrospective study of 1945 individuals. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 3688–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, C.; Yan, W.; Xie, B.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ye, Q.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, D.; Geng, J.; et al. Spectrum of interstitial lung disease in China from 2000 to 2012. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1701554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, T.M. Interstitial Lung Disease: A Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryerson, C.J.; Adegunsoye, A.; Piciucchi, S.; Hariri, L.P.; Khor, Y.H.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Wells, A.U.; Sharma, A.; Cooper, W.A.; Antoniou, K.; et al. Update of the International Multidisciplinary Classification of the Interstitial Pneumonias: An ERS/ATS Statement. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 2500158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szturmowicz, M.; Garczewska, B.; Jędrych, M.E.; Bartoszuk, I.; Sobiecka, M.; Tomkowski, W.; Augustynowicz-Kopeć, E. The value of serum precipitins against specific antigens in patients diagnosed with hypersensitivity pneumonitis—Retrospective study. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 44, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, P.W.; Martusewicz-Boros, M.M.; Lewandowska, K.B. Assessment of lung function and severity grading in interstitial lung diseases (% predicted versus z-scores) and association with survival: A retrospective cohort study of 6808 patients. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e1004619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Bruni, C.; Cuomo, G.; Delle Sedie, A.; Gargani, L.; Gutierrez, M.; Lepri, G.; Ruaro, B.; Santiago, T.; Suliman, Y.; et al. The role of ultrasound in systemic sclerosis: On the cutting edge to foster clinical and research advancement. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2020, 6, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryter, S.W.; Sethi, J.M. Exhaled carbon monoxide as a biomarker of inflammatory lung disease. J. Breath Res. 2007, 1, 026004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, L.-L.; Ning, G.-L.; Teng, X.-B.; Shi, J.-F.; Cui, S.-S.; Cao, Z.-X.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Han, M.-F. Analysis of exhaled nitric oxide and its influencing factors in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1611947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Smith, M.; Guo, Y.; Whitlock, G.; Bian, Z.; Kurmi, O.; Collins, R.; Chen, J.; Lv, S.; et al. Exhaled carbon monoxide and its associations with smoking, indoor household air pollution and chronic respiratory diseases among 512,000 Chinese adults. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabricius, P.; Scharling, H.; Løkke, A.; Vestbo, J.; Lange, P. Exhaled CO, a predictor of lung function? Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradicich, M.; Schuurmans, M.M. Smoking status and second-hand smoke biomarkers in COPD, asthma and healthy controls. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00192-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.K.V.; Ramesh, V.; Castro, C.A.; Kaushik, V.; Kulkarni, Y.M.; Wright, C.A.; Venkatadri, R.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Azad, N. Nitric oxide mediates bleomycin-induced angiogenesis and pulmonary fibrosis via regulation of VEGF. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 2484–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.-S.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.-C.; Wu, L.-L.; Yu, H.-P. Clinical implications of concentration of alveolar nitric oxide in asthmatic and non-asthmatic subacute cough. J. Breath. Res. 2021, 16, 016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Stonham, C.; Rutherford, C.; Pavord, I.D. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO): The future of asthma care? Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2023, 73, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Xu, J.; Zeng, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Yu, H. Differential Clinical Significance of FENO200 and CANO in Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO). J. Asthma Allergy 2024, 17, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Shinkai, M.; Kanoh, S.; Fujikura, Y.; Rubin, B.K.; Kawana, A.; Kaneko, T. Arterial Carboxyhemoglobin Measurement Is Useful for Evaluating Pulmonary Inflammation in Subjects with Interstitial Lung Disease. Intern. Med. 2017, 56, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, P.; Bargagli, E.; Bergantini, L.; d’Alessandro, M.; Pieroni, M.; Fontana, G.A.; Sestini, P.; Refini, R.M. Extended Exhaled Nitric Oxide Analysis in Interstitial Lung Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, H.R.; Ryerson, C.J.; Corte, T.J.; Jenkins, G.; Kondoh, Y.; Lederer, D.J.; Lee, J.S.; Maher, T.M.; Wells, A.U.; Antoniou, K.M.; et al. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An International Working Group Report. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweik, R.A.; Boggs, P.B.; Erzurum, S.C.; Irvin, C.G.; Leigh, M.W.; Lundberg, J.O.; Olin, A.-C.; Plummer, A.L.; Taylor, D.R. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: Interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, I.; Barnes, P.J.; Loukides, S.; Sterk, P.J.; Högman, M.; Olin, A.-C.; Amann, A.; Antus, B.; Baraldi, E.; Bikov, A.; et al. A European Respiratory Society technical standard: Exhaled biomarkers in lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1600965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Ryerson, C.J.; Putman, R.; Oldham, J.; Salisbury, M.; Sverzellati, N.; Valenzuela, C.; Guler, S.; Jones, S.; Wijsenbeek, M.; et al. Early diagnosis of fibrotic interstitial lung disease: Challenges and opportunities. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixey, A.G.; Oh, A.S.; Alsamarraie, A.; Chung, J.H. Pictorial Review of Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease on High-Resolution CT Scan and Updated Classification. Chest 2024, 165, 908–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Crapo, R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Enright, P.; van der Grinten, C.P.M.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. General considerations for lung function testing. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högman, M.; Bowerman, C.; Chavez, L.; Dressel, H.; Malinovschi, A.; Radtke, T.; Stanojevic, S.; Steenbruggen, I.; Turner, S.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. ERS technical standard: Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for exhaled nitric oxide fraction (F ENO50). Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2300370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, A.M.; Balleza, M.; Calaf, N.; González, M.; Feixas, T.; Casan, P. Determining the alveolar component of nitric oxide in exhaled air: Procedures and reference values for healthy persons. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2009, 45, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, S.E.; Deveci, F.; Açik, Y.; Ozan, A.T. The measurement of exhaled carbon monoxide in healthy smokers and non-smokers. Respir. Med. 2004, 98, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuttge, D.M.; Bozovic, G.; Hesselstrand, R.; Aronsson, D.; Bjermer, L.; Scheja, A.; Tufvesson, E. Increased alveolar nitric oxide in early systemic sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, S5–S9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girgis, R.E.; Gugnani, M.K.; Abrams, J.; Mayes, M.D. Partitioning of alveolar and conducting airway nitric oxide in scleroderma lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilleminault, L.; Saint-Hilaire, A.; Favelle, O.; Caille, A.; Boissinot, E.; Henriet, A.C.; Diot, P.; Marchand-Adam, S. Can exhaled nitric oxide differentiate causes of pulmonary fibrosis? Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardolo, F.L.M.; Sorbello, V.; Ciprandi, G. A pathophysiological approach for FeNO: A biomarker for asthma. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2015, 43, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, P.; Bargagli, E.; Refini, R.M.; Pieroni, M.G.; Bennett, D.; Rottoli, P. Exhaled nitric oxide in interstitial lung diseases. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2014, 197, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, P.; Barbagli, E.; Rottoli, P. Exhaled nitric oxide is not increased in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2016, 33, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A.; Mastalerz, M.; Ansari, M.; Schiller, H.B.; Staab-Weijnitz, C.A. Emerging Roles of Airway Epithelial Cells in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Cells 2022, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, J.A.; Wells, A.U.; Cottin, V.; Nicholson, A.G.; Renzoni, E.A. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: Challenges and controversies. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 210177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Khatri, S.B.; Tejwani, V. Measuring exhaled nitric oxide when diagnosing and managing asthma. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2023, 90, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R.; Bernstein, E.J.; Bolster, M.B.; Chung, J.H.; Danoff, S.K.; George, M.D.; Khanna, D.; Guyatt, G.; Mirza, R.D.; Aggarwal, R.; et al. 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Guideline for the Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease in People with Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 1182–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiev, K.P.; Cabane, J.; Aubourg, F.; Kettaneh, A.; Ziani, M.; Mouthon, L.; Duong-Quy, S.; Fajac, I.; Guillevin, L.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. Severity of scleroderma lung disease is related to alveolar concentration of nitric oxide. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 30, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, P.; Bergantini, L.; Salvini, M.; Refini, R.M.; Pieroni, M.; Bargagli, E.; Sestini, P. Alveolar concentration of nitric oxide as a prognostic biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nitric Oxide 2019, 89, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, P.; Bargagli, E.; Bergantini, L.; d’Alessandro, M.; Giugno, B.; Gentili, F.; Sestini, P. Alveolar Nitric Oxide as a Biomarker of COVID-19 Lung Sequelae: A Pivotal Study. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akira, M.; Kozuka, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Sakatani, M. Computed tomography findings in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Kondoh, Y.; Brown, K.K.; Johkoh, T.; Kataoka, K.; Fukuoka, J.; Kimura, T.; Matsuda, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Fukihara, J.; et al. Acute exacerbations of fibrotic interstitial lung diseases. Respirology 2020, 25, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejazi, M.A.; Shameem, M.; Bhargava, R.; Ahmad, Z.; Akhtar, J.; Khan, N.A.; Alam, M.M.; Alam, M.A.; Adil Wafi, C.G. Correlation of exhaled carbon monoxide level with disease severity in chronic obstruction pulmonary disease. Lung India 2018, 35, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofor, L.; Miron, R.; Man, M.A.; Grosu, I.-A.; Trofor, A.C. Correlations between lung function, exhaled carbon monoxide and „lung age” in smokers versus former smokers with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50 (Suppl. S61), PA2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Loukides, S.; Wodehouse, T.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Cole, P.J.; Barnes, P.J. Increased levels of exhaled carbon monoxide in bronchiectasis: A new marker of oxidative stress. Thorax 1998, 53, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I.; Donnelly, L.E.; Kiss, A.; Paredi, P.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Barnes, P.J. Raised levels of exhaled carbon monoxide are associated with an increased expression of heme oxygenase-1 in airway macrophages in asthma: A new marker of oxidative stress. Thorax 1998, 53, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, V.; Wagener, F.A.D.T.G.; Immenschuh, S. The macrophage heme-heme oxygenase-1 system and its role in inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 153, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, T.D.; Agarwal, A.; George, J.F. The mononuclear phagocyte system in homeostasis and disease: A role for heme oxygenase-1. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2014, 20, 1770–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, E.H.; Wang, X.; Balaji, S.; Butte, M.J.; Bollyky, P.L.; Keswani, S.G. The Role of the Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine Interleukin-10 in Tissue Fibrosis. Adv. Wound Care 2020, 9, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-S.; Chau, L.-Y. Heme oxygenase-1 mediates the anti-inflammatory effect of interleukin-10 in mice. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IPF (n = 14) | IPAF (n = 46) | CTD-ILD (n = 177) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Information | Gender (Female/male) | 0/14 | 37/9 | 155/22 |

| Age (years) | 68.57 ± 6.34 | 60.28 ± 12.25 | 53.33 ± 10.85 | |

| Medical History | Smoking history (Y/N) | 12/2 | 9/37 | 23/154 |

| Occupational/Environmental Exposure (Y/N) | 4/10 | 13/33 | 38/139 | |

| Exhaled Biomarkers | FeNO50 (ppb) | 31 ± 13.66 | 21.86 ± 11.05 | 20.17 ± 10.68 |

| FeNO200 (ppb) | 13.25 ± 5.71 | 10.63 ± 5.24 | 10.06 ± 5.25 | |

| CaNO (ppb) | 8.95 ± 6.54 | 5.52 ± 4.29 | 5.53 ± 4.32 | |

| eCO (ppb) | 5.69 ± 3.92 | 6.51 ± 6.08 | 5.59 ± 5.34 | |

| Pulmonary Function Measurements | FVC%Pred | 82.93 ± 19.16 | 87.51 ± 24.15 | 85.16 ± 21.79 |

| DLCO%Pred | 67.54 ± 17.59 | 68.06 ± 18.40 | 69.93 ± 18.52 | |

| Treatment | Hormone | 1 (7.14%) | 2 (4.35%) | 9 (5.08%) |

| Hormone + Immunosuppressive agents | 2 (14.29%) | 8 (17.39%) | 28 (15.82%) | |

| Hormone + Antifibrotic therapy | 1 (7.14%) | 14 (30.43%) | 18 (10.17%) | |

| Hormone + Immunosuppressive agents + Antifibrotic therapy | 7 (50.00%) | 10 (21.74%) | 93 (52.54%) | |

| Antifibrotic therapy | 3 (21.43%) | 5 (10.87%) | 21 (11.86%) | |

| Antifibrotic therapy + Immunosuppressive agents | 0 (0) | 7 (15.22%) | 8 (4.52%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Xie, Q.; Lv, X.; Yu, J.; et al. CaNO and eCO Might Be Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Disease Severity and Exacerbations in Interstitial Lung Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238469

Zhang Y, Wang F, Zhu M, Zhang Y, Xu L, Li L, Li P, Xie Q, Lv X, Yu J, et al. CaNO and eCO Might Be Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Disease Severity and Exacerbations in Interstitial Lung Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238469

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuling, Faping Wang, Min Zhu, Yali Zhang, Linrui Xu, Liangyuan Li, Ping Li, Qibing Xie, Xiaoyan Lv, Jianqun Yu, and et al. 2025. "CaNO and eCO Might Be Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Disease Severity and Exacerbations in Interstitial Lung Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238469

APA StyleZhang, Y., Wang, F., Zhu, M., Zhang, Y., Xu, L., Li, L., Li, P., Xie, Q., Lv, X., Yu, J., Moodley, Y., Wan, H., Mao, H., & Luo, F. (2025). CaNO and eCO Might Be Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Disease Severity and Exacerbations in Interstitial Lung Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238469