Patch Test Preparations: Basis and State-of-the-Art Modern Diagnostic Tools for Contact Allergy

Abstract

1. Introduction

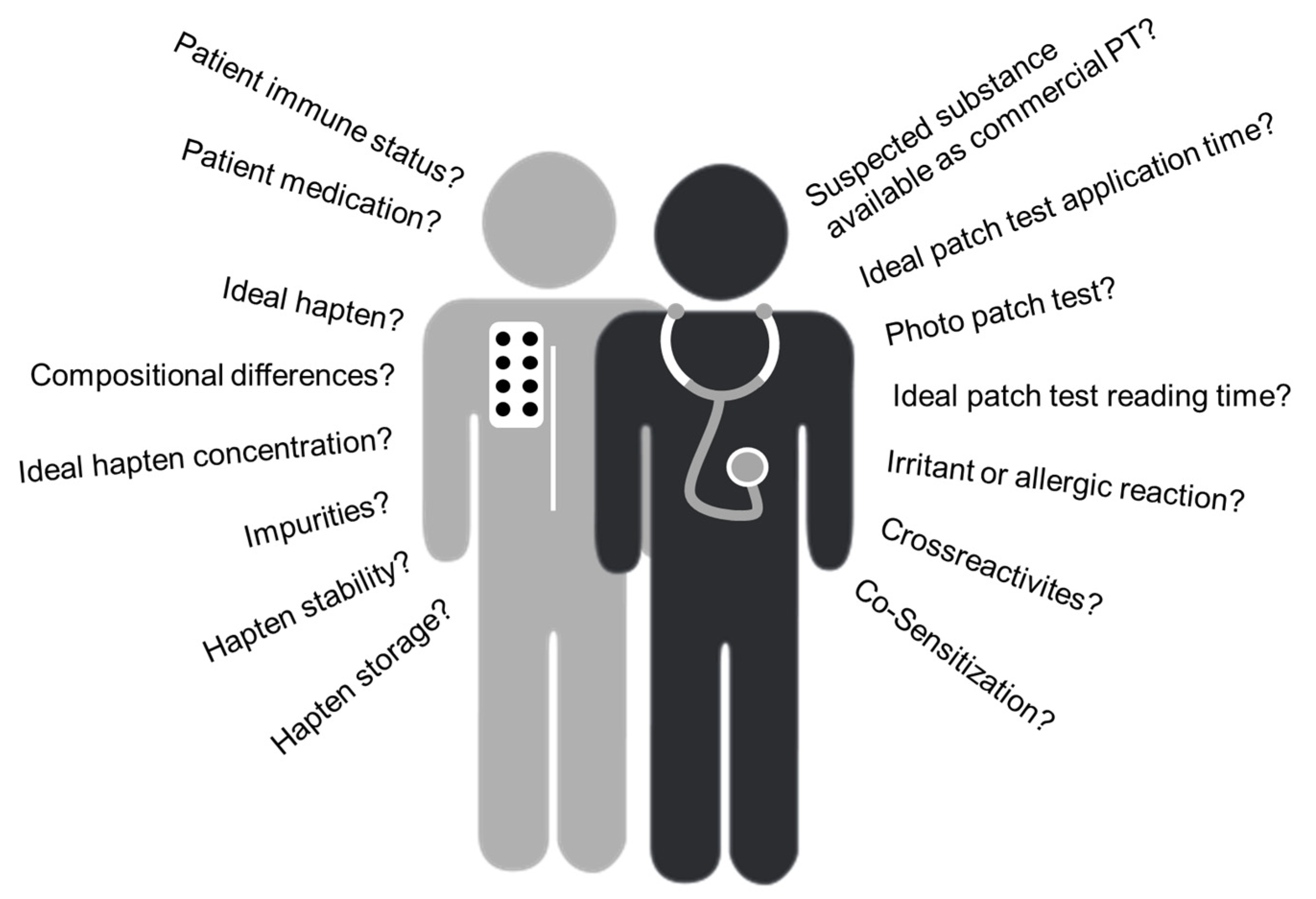

2. Challenges Observed in the Clinic

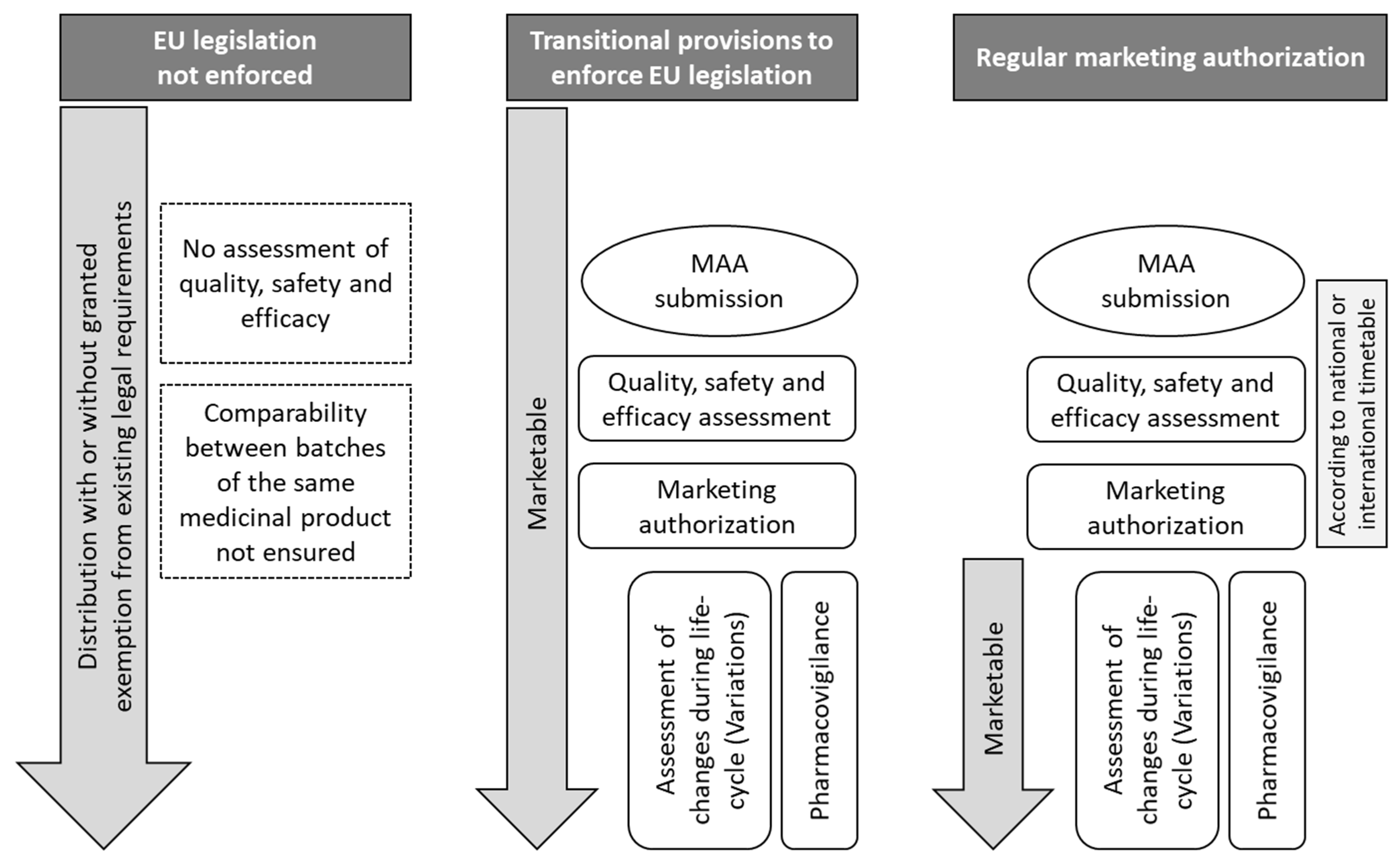

3. Specific Regulatory Practice for Patch Tests

4. Why Use Authorized Products?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Abbreviations

| 2-HEMA | 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| DCP | decentralized procedure |

| DKG | German Contact Dermatitis Research Group |

| EU | European Union |

| GMP | good manufacturing practice |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use |

| LTT | lymphocyte transformation test |

| MA | marketing authorization |

| MAA | marketing authorization application |

| MBT | mercaptobenzothiazole |

| MDBGN | methyldibromoglutaronitrile |

| MMA | methyl methacrylate |

| MRP | mutual recognition procedure |

| MS | member state |

| Ph. Eur. | European Pharmacopoeia |

| PR | positivity ratio |

| PT | patch test |

| PTD | p-toluene diamine |

| RI | reaction index |

| SmPC | summary of product characteristics |

References

- Martin, S.F.; Bonefeld, C.M. Mechanisms of Irritant and Allergic Contact Dermatitis. In Contact Dermatitis, 6th ed.; Duus Johansen, J., Mahler, V., Lepoittevin, J.-P., Frosch, P.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 95–120. ISBN 978-3-030-36334-5. [Google Scholar]

- Groot, A.C.d. Patch Testing: Test Concentrations and Vehicles for 5100 Chemicals, 5th ed.; Acdegroot Publishing: Wapserveen, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 9789081323369. [Google Scholar]

- Popple, A.; Williams, J.; Maxwell, G.; Gellatly, N.; Dearman, R.J.; Kimber, I. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: New opportunities. J. Immunotoxicol. 2016, 13, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Soto, M.; Riedel, F.; Leddermann, M.; Bacher, P.; Scheffold, A.; Kuhl, H.; Timmermann, B.; Chudakov, D.M.; Molin, S.; Worm, M.; et al. TCRs with segment TRAV9-2 or a CDR3 histidine are overrepresented among nickel-specific CD4+ T cells. Allergy 2020, 75, 2574–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, J.; Mahler, V. Regulatory framework for development and marketing authorization of allergen products for diagnosis of rare type I and type IV allergies: The current status. Allergol. Select 2024, 8, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.M.; Bonertz, A.; Zimmer, J.; Aerts, O.; Bauer, A.; Bova, M.; Brans, R.; Del Giacco, S.; Dickel, H.; Corazza, M.; et al. Severely compromised supply of patch test allergens in Europe hampers adequate diagnosis of occupational and non-occupational contact allergy. A European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD), European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) task forces ‘Contact Dermatitis’ and ‘Occupational Skin Disease’ position paper. Contact Dermat. 2024, 91, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonertz, A.; Mahler, V.; Vieths, S. New guidance on the regulation of allergen products: Key aspects and outcomes. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 20, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrevski, M. Post Launch Approval Process for Allergens in Italy (presented atI PES 2023—16th International Paul-Ehrlich-Seminar; September 6—9, 2023, Langen, Germany). Allergologie 2024, 47, 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, J.D.; Aalto-Korte, K.; Agner, T.; Andersen, K.E.; Bircher, A.; Bruze, M.; Cannavó, A.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Gonçalo, M.; Goossens, A.; et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing—Recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermat. 2015, 73, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruze, M.; Isaksson, M.; Gruvberger, B.; Frick-Engfeldt, M. Recommendation of appropriate amounts of petrolatum preparation to be applied at patch testing. Contact Dermat. 2007, 56, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S.; Geier, J.; Brans, R.; Heratizadeh, A.; Kränke, B.; Schnuch, A.; Bauer, A.; Dickel, H.; Buhl, T.; Vieluf, D.; et al. Patch testing hydroperoxides of limonene and linalool in consecutive patients-Results of the IVDK 2018–2020. Contact Dermat. 2023, 89, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, N.; Gaikwad, S.; Holden, C. Sodium benzoate: An important allergen to patch test to—Is 5% in petrolatum too irritant? Br. J. Dermatol. 2023, 188 (Suppl. S4), CD01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokrungsee, S.; Leysen, J.; Aerts, O.; Dendooven, E. Frequent Positive Patch Test Reactions to Glucosides in Children: A Call for Caution? Contact Dermat. 2025, 93, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, J.; Henseler, T.; Aberer, W.; Bauerle, G.; Frosch, P.J.; Fuchs, T.; Funfstuck, V.; Kaiser, G.; Lischka, G.G.; Pilz, B. Reproducibility of patch tests: A multicenter study of synchronous left-versus right-sided patch tests by the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 31, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier, J.; Schnuch, A.; Brasch, J.; Gefeller, O. Patch testing with methyldibromoglutaronitrile. Am. J. Contact Dermat. 2000, 11, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, B.; Geier, J. Dauerbrenner Konservierungsmittelallergie: Was geht, was kommt, was bleibt? Hautarzt 2020, 71, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, A. Linalool Hydroperoxides. Dermatitis 2019, 30, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogueta, I.A.; Brared Christensson, J.; Giménez-Arnau, E.; Brans, R.; Wilkinson, M.; Stingeni, L.; Foti, C.; Aerts, O.; Svedman, C.; Gonçalo, M.; et al. Limonene and linalool hydroperoxides review: Pros and cons for routine patch testing. Contact Dermat. 2022, 87, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, S.M.; Gonçalo, M.; Aerts, O.; Badulici, S.; Dickel, H.; Gallo, R.; Garcia-Abujeta, J.L.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M.; Hamman, C.; Hervella, M.; et al. The European baseline series and recommended additions: 2023. Contact Dermat. 2023, 88, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, A. Limonene Hydroperoxides. Dermatitis 2019, 30, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, J.; Lessmann, H.; Schnuch, A.; Hildebrandt, S.; Uter, W. Patch testing with p-toluene diamine preparations of different ages. Contact Dermat. 2005, 53, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, J.; Uter, W.; Schnuch, A.; Brasch, J.; Gefeller, O. Both mercaptobenzothiazole and mercapto mix should be part of the standard series. Contact Dermat. 2006, 55, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, C.; Agrup, G. Stability of the mercaptobenzothiazole compounds. Contact Dermat. 1993, 28, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowitz, M.; Svedman, C.; Zimerson, E.; Bruze, M. Fragrance patch tests prepared in advance may give false-negative reactions. Contact Dermat. 2014, 71, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontek, K.; Radonjic-Hoesli, S.; Grabbe, J.; Drewitz, K.P.; Apfelbacher, C.; Wöhrl, S.; Simon, D.; Lang, C.; Schubert, S. Comparison of patch testing Brazilian (Green) propolis and Chinese (poplar-type) propolis: Clinical epidemiological study using data from the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK). Contact Dermat. 2025, 92, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oers, E.M.; Ipenburg, N.A.; Groot, A.d.; Calta, E.; Rustemeyer, T. Results of Concurrent Patch Testing of Brazilian and Chinese Propolis. Contact Dermat. 2025, 92, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, A.C. Myroxylon pereirae resin (balsam of Peru)—A critical review of the literature and assessment of the significance of positive patch test reactions and the usefulness of restrictive diets. Contact Dermat. 2019, 80, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, A.C.d.; Schmidt, E. Essential Oils, Part VI: Sandalwood Oil, Ylang-Ylang Oil, and Jasmine Absolute. Dermatitis 2017, 28, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, A.; Mushtaq, A.; Shakeel, R. Risks Associated with Adulterated Essential Oils. IJCBS 2023, 24, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mose, K.F.; Andersen, K.E.; Christensen, L.P. Investigation of the homogeneity of methacrylate allergens in commercially available patch test preparations. Contact Dermat. 2013, 69, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.D.; Fowler, J.F.; Law, B.F.; Warshaw, E.M.; Taylor, J.S. Concentrations and stability of methyl methacrylate, glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde and nickel sulfate in commercial patch test allergen preparations. Contact Dermat. 2014, 70, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Henriks-Eckerman, M.L.; Kanerva, L. Gas chromatographic and mass spectrometric purity analysis of acrylates and methacrylates used as patch test substances. Am. J. Contact Dermat. 1997, 8, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, K.; Gruvberger, B.; Zimerson, E.; Isaksson, M.; Persson, L.; Sorensen, O.; Goossens, A.; Bruze, M. Chemical investigations of disperse dyes in patch test preparations. Contact Dermat. 2008, 58, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uter, W.; Hildebrandt, S.; Geier, J.; Schnuch, A.; Lessmann, H. Current patch test results in consecutive patients with, and chemical analysis of, disperse blue (DB) 106, DB 124, and the mix of DB 106 and 124. Contact Dermat. 2007, 57, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piontek, K.; Schubert, S. Dyes, pigments and inks. In Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology; John, S.M., Johansen, J.D., Rustemeyer, T., Elsner, P., Maibach, H.I., Eds.; Springer International PU: Basel, Switzerland, 2025; ISBN 3031421051. (In Press)

- Mahler, V.; Nast, A.; Bauer, A.; Becker, D.; Brasch, J.; Breuer, K.; Dickel, H.; Drexler, H.; Elsner, P.; Geier, J.; et al. S3 Guidelines: Epicutaneous patch testing with contact allergens and drugs—Short version, Part 2. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2019, 17, 1187–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, A.; Waldek, S. It is time to review how unlicensed medicines are used. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pharmacopoeia. Monograph on Allergen Products (1063). Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Allergen Products: Production and Quality Issues (EMEA/CHMP/BWP/304831/2007). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/allergen-products-production-quality-issues-scientific-guideline (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Allergen Products Development for Immunotherapy and Allergy Diagnosis in Moderate to Lowsized Study Populations (EMA/161669/2025). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/allergen-products-development-immunotherapy-allergy-diagnosis-moderate-low-sized-study-populations-scientific-guideline (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Process Validation for Finished Products—Information and Data to be Provided in Regulatory Submissions (EMA/CHMP/CVMP/QWP/BWP/70278/2012-Rev1,Corr.1). 2016. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-process-validation-finished-products-information-and-data-be-provided-regulatory-submissions-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Clinical Evaluation of Diagnostic Agents (CPMP/EWP/1119/98/Rev. 1). 2009. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-evaluation-diagnostic-agents-scientific-guideline (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Brasch, J.; Henseler, T. The reaction index: A parameter to assess the quality of patch test preparations. Contact Dermat. 1992, 27, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, J.; Geier, J. How to use the reaction index and positivity ratio. Contact Dermat. 2008, 59, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1234/2008 of 24 November 2008 Concerning the Examination of Variations to the Terms of Marketing Authorisations for Medicinal Products for Human Use and Veterinary Medicinal Products. 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/1234/oj/eng (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Joy, N.M.; Rice, K.R.; Atwater, A.R. Stability of patch test allergens. Dermatitis 2013, 24, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Application | Legal Basis | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Full marketing authorization | Article 8(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC | Based on the full data set, including product-specific data from clinical studies |

| Mixed marketing authorization | Article 8(3) in combination with Annex I Part II Section 7 of Directive 2001/83/EC | Based on a combination of reports from limited non-clinical and/or clinical studies and bibliographical references |

| Well-established use | Article 10a of Directive 2001/83/EC | Based on appropriate scientific literature, if the active substances have been in well-established medicinal use within the EU for at least 10 years and if efficacy and safety are evident |

| Standard Regulatory Requirements for In Vivo Diagnostics | Adapted Requirements for PT preparations |

|---|---|

| Quality | |

| Validation of the manufacturing process for each product | Option of matrix approach for process validation in case of an identical production process |

| GMP requirements must be fulfilled throughout the manufacturing process | Waiver of GMP requirements for active substance production at the supplier |

| Details on the manufacturing of the active substance need to be presented in the product dossier | Absence of information on active substance manufacturing is acceptable |

| A full set of stability data (in accordance with ICH requirements) needs to be submitted for MA | Commitments for stability studies may be acceptable when long-term stability data for at least one batch are available |

| Non-clinic | |

| Collection of non-clinical data in corresponding animal studies | Option of compilation of already existing data from the literature |

| Clinic | |

| Performance of Phase II dose-finding studies necessary to select the appropriate concentration | Data from expert associations and/or suitable literature can support the selection of an appropriate concentration |

| Phase III confirmatory efficacy trials necessary | Relevant data from registries may be acceptable |

| Determination of sensitivity and specificity | Option to use alternative parameters like reaction index and positivity ratio |

| Potential Quality Deficiencies | Resulting Potential Clinical Consequences (Impaired Reliability of Diagnosis and/or Safety) | Regulatory Countermeasures (Requirements for Each Hapten (no Extrapolation Possible): |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing errors | ||

| Wrong active substance, e.g., due to a mix-up during production or a mistake by the supplier | - test result invalid, leading to a false diagnosis Depending on the nature of the wrong active substance: - risk of active sensitization or other adverse reactions | - active substance identity control using validated methods in the finished product |

| Suboptimal concentration of active substance, e.g., due to weighing error, or a missing definition of active substance shelf-life or general absence of content control by manufacturers | Depending on the extent of deviation from the labelled/recommended active substance concentration: - risk of false-negative results - risk of excessive positive reactions - risk of irritant or other adverse reactions - risk of active sensitization | - routine control of the manufacturing process - control of active substance content using validated methods both at release and in stability studies - definition of active substance shelf-life prior to and after initial opening of container |

| Inhomogeneity e.g., due to insufficient stirring during production | Depending on the extent of inhomogeneity and thus deviation from the labelled/recommended active substance concentration in the applied dose: - risk of false-negative results - risk of excessive positive reactions - risk of irritant or other adverse reactions | - control of homogeneity at release and in guideline-conforming stability studies in a validated method - validation of the manufacturing process, at least for a set of representative products |

| Hapten-specific problems | ||

| Degradation or evaporation of active substance, e.g., during manufacturing and/or storage | Depending on the extent of deviation from the labelled/recommended active substance concentration: - risk of false-negative results - risk of irritant or other adverse reactions due to potentially harmful degradation products | - routine control of the manufacturing process - shelf-life determined based on stability data generated using validated methods in guideline-conform stability studies - photostability studies if the product is not stored protected from light |

| Reactions between the hapten and the container | Depending on the nature and extent of interaction: - risk of false-negative results - risk of false-positive results - irritant reactions | - assessment of the suitability of the container closure system - control of patch test quality in guideline-conform stability studies |

| Particle growth or formation, e.g., during manufacturing and/or storage | Depending on particle size/hapten: - sandpaper effect - potentially reduced bioavailability of the active substance - irritant reactions | - control of particle size at release and in guideline-conform stability studies in a validated method |

| Contaminations | ||

| Contamination with impurities, e.g., due to the supplier’s manufacturing process or source material | Depending on the nature of impurity: - risk of false-positive results - risk of irritant reactions | - active substance content control in validated methods in the finished product - information on impurities to be provided for MAA - control of critical impurities by patch test manufacturer (if not controlled by supplier) |

| Contamination with other haptens, e.g., due to insufficient line clearance/cleaning regime | - risk of false-positive results - risk of active sensitization or other adverse reactions | - active substance content control in validated methods in the finished product - GMP requirements are effective upon active substance arrival at the PT manufacturer |

| Microbiological contamination, e.g., in the case of natural substances | - in case of, e.g., irritant patch test reaction, risk of infection - risk of false-positive reactions | - control of microbiological quality at finished product release and in stability studies using Ph. Eur. methods |

| Product life-cycle | ||

| Change in critical active substance quality parameters due to a change in the supplier | Depending on the extent of difference between active substances: - no reproducibility of test results - risk of false-negative results - risk of excessive positive reactions - risk of irritant and other adverse reactions | - assessment of comparability pre/post change in active substance supplier and finished product batch-to-batch consistency in the mandatory variation procedure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zimmer, J.; Neimanis, S.; Schmidt, S.; Schubert, S.; Mahler, V. Patch Test Preparations: Basis and State-of-the-Art Modern Diagnostic Tools for Contact Allergy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217521

Zimmer J, Neimanis S, Schmidt S, Schubert S, Mahler V. Patch Test Preparations: Basis and State-of-the-Art Modern Diagnostic Tools for Contact Allergy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217521

Chicago/Turabian StyleZimmer, Julia, Sonja Neimanis, Sandra Schmidt, Steffen Schubert, and Vera Mahler. 2025. "Patch Test Preparations: Basis and State-of-the-Art Modern Diagnostic Tools for Contact Allergy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217521

APA StyleZimmer, J., Neimanis, S., Schmidt, S., Schubert, S., & Mahler, V. (2025). Patch Test Preparations: Basis and State-of-the-Art Modern Diagnostic Tools for Contact Allergy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217521