Methylxanthines: The Major Impact of Caffeine in Clinical Practice in Patients Diagnosed with Apnea of Prematurity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Question and Objectives

- Population (P): Preterm infants (<37 weeks of gestation) diagnosed with apnea of prematurity (AOP).

- Intervention (I): Any methylxanthine therapy (caffeine, theophylline, aminophylline), administered by any route or regimen.

- Comparator (C): Placebo, no treatment, or another methylxanthine compound.

- Outcomes (O): Primary—reduction in apnea frequency or severity. Secondary—extubation success, duration of mechanical ventilation, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, mortality, and adverse events.

3. Methods

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Preterm infants (<37 weeks’ gestation) or with low birth weight (<2500 g) experiencing apnea of prematurity.

- Intervention: Caffeine, theophylline, or aminophylline used for prophylaxis or treatment of AOP, via any route (intravenous, oral, nasogastric).

- Comparator: Placebo, no treatment, or other methylxanthine compounds.

- Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and case–control studies.

- Outcomes: At least one clinically relevant respiratory or safety outcome reported.

- Studies involving term infants (≥37 weeks’ gestation) or apnea due to other causes (e.g., sepsis, seizures, metabolic disorders).

- Studies limited to pharmacokinetic data without clinical outcomes.

- Non-methylxanthine interventions only.

- Case reports, reviews, editorials, or conference abstracts without extractable data.

- Studies from before 1970.

3.2. Search Strategy

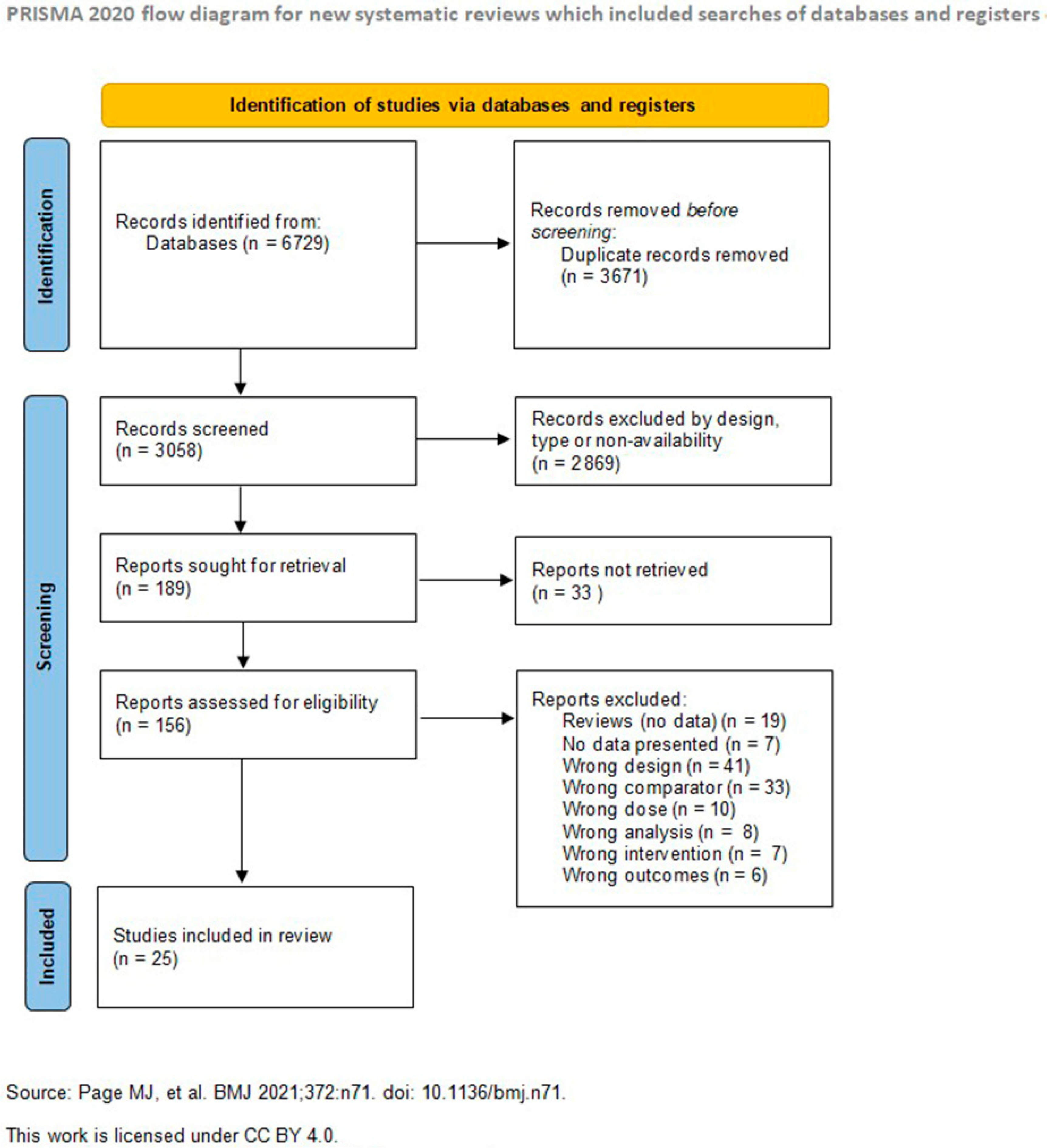

3.3. Study Selection Process

3.4. Data Extraction

- Study characteristics (authors, year, country, design, sample size);

- Population demographics (gestational age, birth weight);

- Intervention details (methylxanthine type, dose, route, duration);

- Comparator characteristics;

- Primary and secondary outcomes (efficacy, safety, respiratory support);

- Risk of bias elements.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

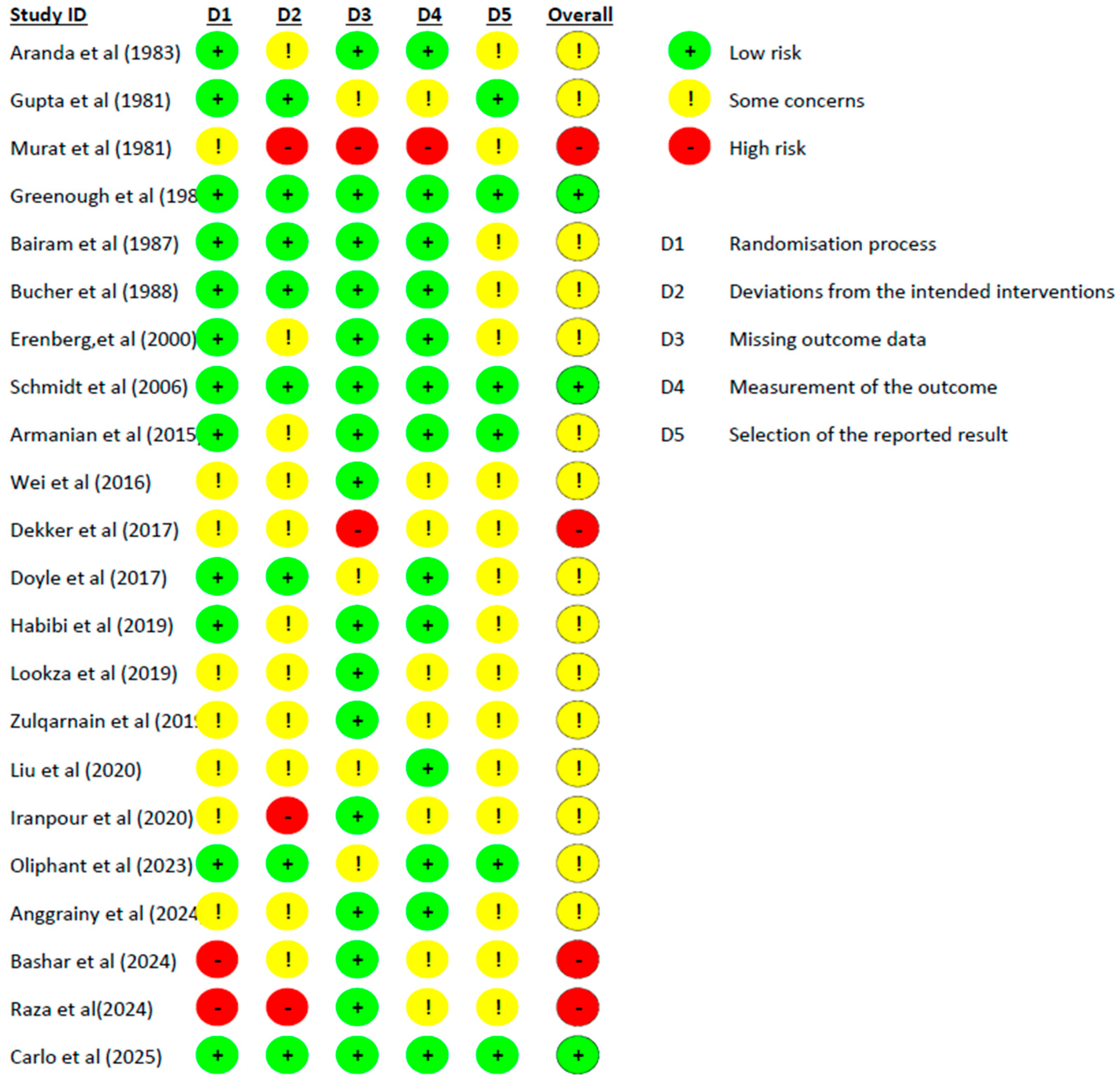

4.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

4.3. Synthesis of Results

4.4. Certainty of Evidence, Heterogeneity, and Sensitivity Analysis

4.4.1. Certainty of the Body of Evidence

4.4.2. Exploration of Heterogeneity

4.4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

4.5. Efficacy in Apnea Reduction

4.6. Respiratory Support and Extubation Success

4.7. Safety Profile and Adverse Effects

4.8. Comparative Effectiveness of Caffeine Versus Theophylline

4.9. Long-Term Outcomes

4.10. Dosing Strategies and Treatment Protocols

5. Discussion

5.1. Clinical Implications

5.1.1. Evidence-Based Practice Recommendations

5.1.2. Implications for Neonatal Intensive Care Practice

5.1.3. Economic and Health System Implications

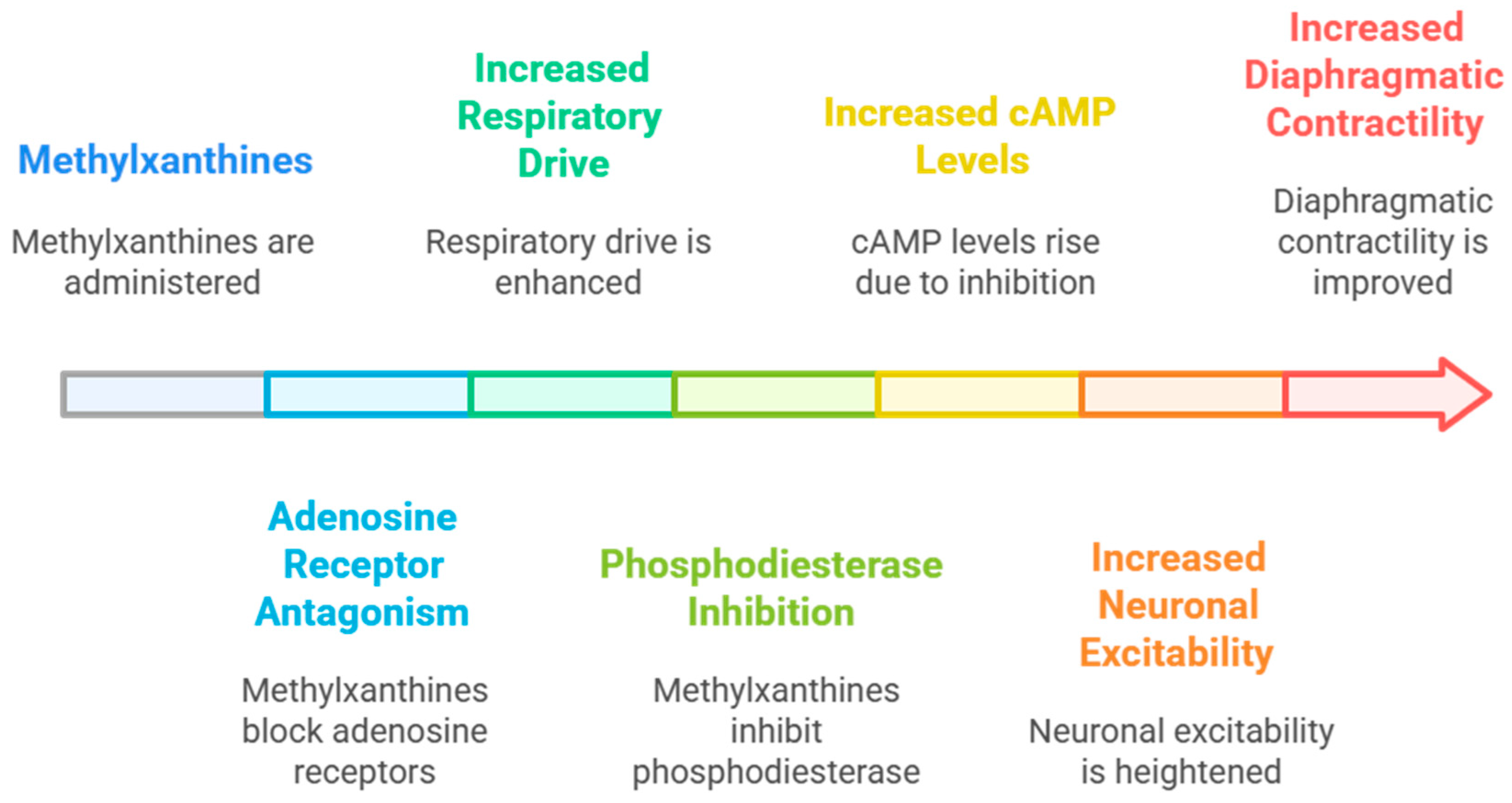

5.2. Mechanistic Insights and Future Directions

5.2.1. Mechanistic Interpretation of Clinical Benefits

5.2.2. Variability in Response and Sources of Uncertainty

- Lack of standardized biomarkers to monitor caffeine responsiveness and optimal discontinuation timing.

- Minimal data on extremely low birth-weight (<1000 g) infants, who may require altered dosing intervals.

- Unclear impact of concomitant medications and environmental factors (hypoxia, infection, nutrition) on caffeine efficacy.

- Absence of large-scale pharmacogenomic studies to identify genetic determinants of treatment variability.

5.2.3. Directions for Future Research

5.3. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

5.3.1. Limitations of the Review Process

5.3.2. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

5.3.3. Outcome Definition Variability

5.3.4. Population Heterogeneity

5.4. Gaps in Current Knowledge

5.4.1. Optimal Treatment Duration

5.4.2. Combination Therapies

5.4.3. Long-Term Safety

5.5. Research Priorities

5.5.1. Mechanistic Studies

5.5.2. Personalized Medicine Approaches

5.5.3. Novel Delivery Methods

5.6. Clinical Practice Implications

- Caffeine citrate should be considered first-line therapy for apnea of prematurity in preterm infants.

- A standard dosing protocol consisting of a 20 mg/kg loading dose followed by a 5 mg/kg daily maintenance dose is well established.

- Routine monitoring of plasma methylxanthine levels can facilitate individualized therapy and ensure that therapeutic effects are achieved safely and effectively.

- The LC–MS method validated at the Research Center of the Faculty of Pharmacy in Craiova can be employed to determine real plasma titers of caffeine and theophylline in infants with apnea of prematurity, supporting personalized dosing strategies.

- Early initiation of methylxanthine therapy within the first days of life provides optimal benefits in reducing apnea frequency, facilitating extubation, and lowering bronchopulmonary dysplasia risk.

- Treatment duration should continue until apnea episodes resolve, typically by 34–37 postmenstrual weeks of age.

5.7. Take-Home Messages

- Caffeine citrate should be considered first-line treatment for apnea of prematurity in preterm infants.

- A standard dosing regimen of 20 mg/kg loading dose followed by 5 mg/kg daily maintenance is well established and widely validated.

- Selective monitoring in infants with variable metabolism or clinical instability ensures of plasma methylxanthine levels enables individualized dosing that therapeutic effects remain within safe limits.

- The LC–MS method validated at the Research Center of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Craiova, can be used to determine accurate plasma titers of caffeine and theophylline in infants with apnea of prematurity.

- Early initiation of methylxanthine therapy within the first 72 h of life yields optimal respiratory and neurodevelopmental benefits.

- Therapy should be continued until apnea episodes resolve, usually between 34 and 37 postmenstrual weeks of age.

- Integration of caffeine therapy into kangaroo mother care, early feeding, and thermal regulation programs enhances its feasibility and impact in resource-limited settings.

- The long-term benefits of caffeine—improved neurological, respiratory, and growth outcomes—support its inclusion in international guidelines such as the World Health Organization (2023) Recommendations for Care of Preterm or Low Birth Weight Infants [81].

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pergolizzi, J.; Kraus, A.; Magnusson, P.; Breve, F.; Mitchell, K.; Raffa, R.; LeQuang, J.A.K.; Varrassi, G. Treating Apnea of Prematurity. Cureus 2022, 14, e21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamţu, S.; Găman, G.; Stanca, L.; Buzatu, I.; Dijmărescu, L.; Manolea, M. The Contribution of Laboratory Investigations in Diagnosis of Congenital Infections. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2011, 52, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Neamţu, S.D.; Novac, M.B.; Neamţu, A.V.; Stanca, I.D.; Boldeanu, M.V.; Gluhovschi, A.; Stanca, L.; Dijmărescu, A.L.; Manolea, M.M.; Trăistaru, M.R.; et al. Fetal-Maternal Incompatibility in the Rh System. Rh Isoimmunization Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis: Case Presentation and Review of the Literature. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2022, 63, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camen, I.V.; Istrate-Ofiţeru, A.M.; Novac, L.V.; Manolea, M.M.; Dijmărescu, A.L.; Neamţu, S.D.; Radu, L.; Boldeanu, M.V.; Şerbănescu, M.S.; Stoica, M.; et al. Analysis of the Relationship between Placental Histopathological Aspects of Preterm and Term Birth. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2022, 63, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, C.E.; Corwin, M.J.; Weese-Mayer, D.E.; Davidson Ward, S.L.; Ramanathan, R.; Lister, G.; Tinsley, L.R.; Heeren, T.; Rybin, D. Longitudinal Assessment of Hemoglobin Oxygen Saturation in Preterm and Term Infants in the First Six Months of Life. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, S.; Max, E.E. Immunology, Immunopathology, and Immunity, 6th ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, T.A.; Schroeder, H.W. Clinical Immunology: Principles and Practice: Expert Consult with Updates; Mosby; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; ISBN 0323044042. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Davis, P.; Doyle, L.W.; Barrington, K.J.; Ohlsson, A.; Solimano, A.; Tin, W. Caffeine Therapy for Apnea of Prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotzbach, S.F.; Baldwin, R.B.; Lederer, N.E.; Tansey, P.A.; Ariagno, R.L. Periodic Breathing in Preterm Infants: Incidence and Characteristics. Pediatrics 1989, 84, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.J.; Wilson, C.G. Apnea of Prematurity. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 2923–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, H.C.; Costarino, A.T.; Stayer, S.A.; Brett, C.M.; Cladis, F.; Davis, P.J. Outcomes for Extremely Premature Infants. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 120, 1337–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, G. Respiratory Control in the Newborn: Comparative Physiology and Clinical Disorders. In Respiratory Control and Disorders in the Newborn; Mathew, O.P., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, O.P. Apnea of Prematurity: Pathogenesis and Management Strategies. J. Perinatol. 2011, 31, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poets, C.F. Apnea of Prematurity: What Can Observational Studies Tell Us about Pathophysiology? Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch-Salisbury, E.; Hall, M.H.; Sharma, P.; Boyd, T.; Bednarek, F.; Paydarfar, D. Heritability of Apnea of Prematurity: A Retrospective Twin Study. Pediatrics 2010, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatto, H. Breathing and Sleep in Preterm. In Sleep and Breathing in Children, a Developmental Approach; Carroll, G.M., Marcus, J.L., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 495–523. [Google Scholar]

- Rassameehiran, S.; Klomjit, S.; Hosiriluck, N.; Nugent, K. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Proton Pump Inhibitors on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Symptoms and Indices in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2016, 29, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson-Smart, D.J.; Pettigrew, A.G.; Campbell, D.J. Clinical Apnea and Brain-Stem Neural Function in Preterm Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 308, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andropoulos, D.B. Pediatric Normal Laboratory Values. In Gregory’s Pediatric Anesthesia, 5th ed.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschettini, M.; Brattström, P.; Russo, C.; Onland, W.; Davis, P.G.; Soll, R. Caffeine Dosing Regimens in Preterm Infants with or at Risk for Apnea of Prematurity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 4, CD013873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, D.G.; Carnielli, V.P.; Greisen, G.; Hallman, M.; Klebermass-Schrehof, K.; Ozek, E.; Te Pas, A.; Plavka, R.; Roehr, C.C.; Saugstad, O.D.; et al. European Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome: 2022 Update. Neonatology 2023, 120, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, A. Surfactant for Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Neoreviews 2014, 15, e236–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneman, M.W.; Madhok, J.; Weimer, J.M.; Dalia, A.A. Perioperative Implications of the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Drug-Induced Arrhythmias-A Focused Review. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2022, 36, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenwald, E.C. Apnea of Prematurity. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschino, L.; Zivanovic, S.; Hartley, C.; Trevisanuto, D.; Baraldi, E.; Roehr, C.C. Caffeine in Preterm Infants: Where Are We in 2020? ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00330-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoen, K.; Yu, T.; Stockmann, C.; Spigarelli, M.G.; Sherwin, C.M.T. Use of Methylxanthine Therapies for the Treatment and Prevention of Apnea of Prematurity. Pediatr. Drugs 2014, 16, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Katsuma, A.; Mito, A.; Tamura, K.; Makimoto, M.; Yoshida, T. Pharmacokinetic Variability of Caffeine in Routinely Treated Preterm Infants: Preliminary Considerations on Developmental Changes of Systemic Clearance. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nix, D.E.; Devito, J.M.; Whitbread, M.A.; Schentag, J.J. Effect of Multiple Dose Oral Ciprofloxacin on the Pharmacokinetics of Theophylline and Indocyanine Green. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1987, 19, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, R.J.; Bales, P.D.; Himwich, H.E. The Effects of DFP on the Convulsant Dose of Theophylline, Theophylline-Ethylenediamine and 8-Chlorotheophylline. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1951, 101, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennmalm, A.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Wennmalm, M. Effect of Aminophylline on Plasma and Urinary Catecholamine Levels during Heavy Leg Exercise in Healthy Young Men. Clin. Sci. 1989, 76, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacrétaz, A.; Vandenberghe, F.; Glatard, A.; Levier, A.; Dubath, C.; Ansermot, N.; Crettol, S.; Gholam-Rezaee, M.; Guessous, I.; Bochud, M.; et al. Association Between Plasma Caffeine and Other Methylxanthines and Metabolic Parameters in a Psychiatric Population Treated with Psychotropic Drugs Inducing Metabolic Disturbances. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.V.; Devi, R.; Kumar, G. Non-Invasive Ventilation in Neonates: A Review of Current Literature. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1248836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.N.K.; Mercer, B.M.; Burchfield, D.J.; Joseph, G.F. Periviable Birth: Executive Summary of a Joint Workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. J. Perinatol. 2014, 34, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenough, A.; Elias-Jones, A.; Pool, J.; Morley, C.J.; Davis, J.A. The Therapeutic Actions of Theophylline in Preterm Ventilated Infants. Early Hum. Dev. 1985, 12, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugino, M.; Kuboi, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Nishioka, K.; Tadatomo, Y.; Kawaguchi, N.; Sadamura, T.; Nakano, A.; Konishi, Y.; Koyano, K.; et al. Serum Caffeine Concentrations in Preterm Infants: A Retrospective Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.A. Advanced Neuroimaging and Its Role in Predicting Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Very Preterm Infants. Semin. Perinatol. 2016, 40, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neamțu, A.V.; Manda, C.V.; Croitoru, O.; Popescu, M.D.E.; Calucică, D.M.; Neamțu, J.; Biță, A.; Stanca, L.; Siminel, M.A.; Neamțu, S.D. Porous Graphitic Carbon Column in Quantitation of Caffeine in Preterm Infants’ Serum Samples. Farmacia 2025, 73, 942–948. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, J.V.; Turmen, T.; Davis, J.; Trippenbach, T.; Grondin, D.; Zinman, R.; Watters, G. Effect of Caffeine on Control of Breathing in Infantile Apnea. J. Pediatr. 1983, 103, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.M.; Mercer, H.P.; Koo, W.W.K. Theophylline in Treatment of Apnoea of Prematurity. Aust. Paediatr. J. 1981, 17, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, I.; Moriette, G.; Blin, M.C.; Couchard, M.; Flouvat, B.; De Gamarra, E.; Relier, J.P.; Dreyfus-Brisac, C. The Efficacy of Caffeine in the Treatment of Recurrent Idiopathic Apnea in Premature Infants. J. Pediatr. 1981, 99, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairam, A.; Boutroy, M.J.; Badonnel, Y.; Vert, P. Theophylline versus Caffeine: Comparative Effects in Treatment of Idiopathic Apnea in the Preterm Infant. J. Pediatr. 1987, 110, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, H.U.; Duc, G. Does Caffeine Prevent Hypoxaemic Episodes in Premature Infants? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1988, 147, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenberg, A.; Leff, R.D.; Haack, D.G.; Mosdell, K.W.; Hicks, G.M.; Wynne, B.A. Caffeine Citrate for the Treatment of Apnea of Prematurity: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Pharmacotherapy 2000, 20, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.; Kim, H.S.; Song, E.S.; Choi, Y.Y. Comparison between Caffeine and Theophylline Therapy for Apnea of Prematurity. Neonatal Med. 2015, 22, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanian, A.M.; Iranpour, R.; Faghihian, E.; Salehimehr, N. Caffeine Administration to Prevent Apnea in Very Premature Infants. Pediatr. Neonatol 2016, 57, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.Z.; Su, P.; Han, J.T.; Zhang, X.; Duan, Y.H. Effect of Early Caffeine Treatment on the Need for Respirator Therapy in Preterm Infants with Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2016, 18, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, J.; Hooper, S.B.; Van Vonderen, J.J.; Witlox, R.S.G.M.; Lopriore, E.; Te Pas, A.B. Caffeine to Improve Breathing Effort of Preterm Infants at Birth: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 82, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.W.; Ranganathan, S.; Cheong, J.L.Y. Neonatal Caffeine Treatment and Respiratory Function at 11 Years in Children under 1,251 g at Birth. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, M.; Mahyar, A.; Nikdehghan, S. Effect of Caffeine and Aminophylline on Apnea of Prematurity. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2019, 10, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosein Lookzadeh, M.; Jafari-Abeshoori, E.; Noorishadkam, M.; Reza Mirjalili, S.; Reza Mohammadi, H.; Emambakhshsani, F. Caffeine versus Aminophylline for Apnea of Prematurity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. World J. Peri Neonatol. 2019, 2, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulqarnain, A.; Hussain, M.; Suleri, K.M.; Ali Ch, Z. Comparison of Caffeine versus Theophylline for Apnea of Prematurity. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakoor, Z.; Makooie, A.; Joudi, Z.; Asl, R. The Effect of Venous Caffeine on the Prevention of Apnea of Prematurity in the Very Preterm Infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Shahid Motahhari Hospital, Urmia, during a Year. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2019, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Zhu, C. Early Application of Caffeine Improves White Matter Development in Very Preterm Infants. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2020, 281, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Tan, Y.L.; Yen, T.A.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsao, P.N.; Chou, H.C. Specific Premature Groups Have Better Benefits When Treating Apnea with Caffeine Than Aminophylline/Theophylline. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 817624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, E.A.; Mckinlay, C.J.D.; Mcnamara, D.; Cavadino, A.; Alsweiler, J.M. Caffeine to Prevent Intermittent Hypoxaemia in Late Preterm Infants: Randomised Controlled Dosage Trial. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023, 108, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggrainy, N.; Sarosa, G.I.; Suswihardhyono, A.N.R. Comparison of Oral Caffeine and Oral Theophylline for Apnea of Prematurity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Paediatr. Indones. 2024, 64, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashar, A.R.; Hameed, S.A.W.; Khaleq, H.L.A. Compare the Efficacy and the Safety of Caffeine versus Aminophylline for Prophylaxis and Treatment of Apnea of Prematurity in Preterm Neonates (≤34 Weeks). Int. J. Paediatr. Geriatr. 2024, 7, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool Raza, A.; Zulfiqar, A.; Nawaz, N. An Experience in Tertiary Care Unit: Comparison between Efficacy of Caffeine Versus Aminophylline in Apnea of Prematurity. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2024, 18, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, W.A.; Eichenwald, E.C.; Carper, B.A.; Bell, E.F.; Keszler, M.; Patel, R.M.; Sánchez, P.J.; Goldberg, R.N.; D’Angio, C.T.; Van Meurs, K.P.; et al. Extended Caffeine for Apnea in Moderately Preterm Infants: The MoCHA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 2154–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranpour, R.; Armanian, A.M.; Miladi, N.; Feizi, A. Effect of Prophylactic Caffeine on Noninvasive Respiratory Support in Preterm Neonates Weighing 1250-2000 g: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Iran. Med. 2022, 25, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, E.A.; Hanning, S.M.; McKinlay, C.J.D.; Alsweiler, J.M. Caffeine for Apnea and Prevention of Neurodevelopmental Impairment in Preterm Infants: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Perinatol. 2024, 44, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington, K.J.; Finer, N.N. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Aminophylline in Ventilatory Weaning of Premature Infants. Crit. Care Med. 1993, 21, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Davis, P.; Doyle, L.W.; Barrington, K.J.; Ohlsson, A.; Solimano, A.; Tin, W. Long-Term Effects of Caffeine Therapy for Apnea of Prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Brozek, J.; Glasziou, P.; Jaeschke, R.; Vist, G.E.; Williams, J.W.; Kunz, R., Jr.; Craig, J.; Montori, V.M.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008, 336, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, R.E. Control of Breathing and Apnea of Prematurity. Neoreviews 2018, 19, e224–e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, G.; Dobson, N.R.; Hunt, C.E. Immature Control of Breathing and Apnea of Prematurity: The Known and Unknown. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 2111–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kua, K.P.; Lee, S.W.H. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes of Early Caffeine Therapy in Preterm Neonates. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, D.J.; Goodman, A.; Ray, P.; Ballard, R.A.; Clyman, R.I. Theophylline Treatment in the Extubation of Infants Weighing Less than 1,250 Grams: A Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 1987, 80, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias-Jones, A.C.; Dhillon, S.; Greenough, A. The Efficacy of Oral Theophylline in Ventilated Premature Infants. Early Hum. Dev. 1985, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.Z.; Azab, S.S.; Khattab, A.R.; Farag, M.A. Over a Century since Ephedrine Discovery: An Updated Revisit to Its Pharmacological Aspects, Functionality and Toxicity in Comparison to Its Herbal Extracts. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 9563–9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamatari, M. Inhaled Theophylline: Old Drug New Tricks? Int. J. Basic Amp. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Moustafa, H. EBNEO Commentary: Caffeine to Prevent Intermittent Hypoxaemia in Late Preterm Infants: Randomised Controlled Dosage Trial. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenough, A. Long-Term Respiratory Consequences of Premature Birth at Less than 32 Weeks of Gestation. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, S25–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Bancalari, E. Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Clinical Perspective. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2014, 100, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbreen, H.; Qureshi, A.N.; Shahid, S.; Naheed, I.; Abdullah, H.M. Comparison of the Efficacy of Caffeine with Aminophylline for Management of Infants having Apnea of Prematurity. Ind. J. Bio. Res. 2025, 3, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Huang, C. Adverse Drug Reactions in Primary Care: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, B.T.; Shi, J.; Ferraro, J.P.; Skarda, D.E.; Samore, M.H.; Hurdle, J.F.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Chapman, W.W.; Finlayson, S.R.G. Portable Automated Surveillance of Surgical Site Infections Using Natural Language Processing: Development and Validation. Ann. Surg. 2020, 272, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Valdez, R.; Wills-Karp, M.; Ahlawat, R.; Cristofalo, E.A.; Nathan, A.; Gauda, E.B. Caffeine Modulates TNF-Alpha Production by Cord Blood Monocytes: The Role of Adenosine Receptors. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 65, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmstadt, G.L.; Al Jaifi, N.H.; Arif, S.; Bahl, R.; Blennow, M.; Cavallera, V.; Chou, D.; Chou, R.; Comrie-Thomson, L.; Edmond, K.; et al. New World Health Organization Recommendations for Care of Preterm or Low Birth Weight Infants: Health Policy. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 63, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, S.; Banerjee, S. Fluid, Electrolyte and Early Nutritional Management in the Preterm Neonate with Very Low Birth Weight. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 31, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, C.S. A New Look at the Respiratory Stimulant Doxapram. CNS Drug Rev. 2006, 12, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillekamp, F.; Hermann, C.; Keller, T.; Von Gontard, A.; Kribs, A.; Roth, B. Factors Influencing Apnea and Bradycardia of Prematurity—Implications for Neurodevelopment. Neonatology 2007, 91, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, N.R.; Patel, R.M.; Smith, P.B.; Kuehn, D.R.; Clark, J.; Vyas-Read, S.; Herring, A.; Laughon, M.M.; Carlton, D.; Hunt, C.E. Trends in Caffeine Use and Association between Clinical Outcomes and Timing of Therapy in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenwald, E.C.; Hansen, A.R.; Martin, C.; Stark, A.R. Cloherty and Stark’s Manual of Neonatal Care, 8th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer Business: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-496343-61-1. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, J.V.; Beharry, K.D. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Metabolism of Caffeine in Newborns. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 25, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outcome Category | Definition/Measurement | Effect Measures Reported in Included Studies | Summary of Findings (Synthesis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea Reduction | Reduction in frequency or severity of apneic episodes (>15–20 s cessations) measured via cardiorespiratory monitoring. | Proportion achieving ≥ 50% reduction [44], mean difference in episodes/day [40,57], RR or OR where available. | All studies reported significant reductions in apnea frequency with methylxanthines vs. placebo. Example: CAP trial [8]: Caffeine significantly reduced apnea and oxygen need; Erenberg trial [44] showed ≥50% reduction in apnea episodes (68.9% success). Overall qualitative synthesis supports caffeine as superior to placebo and equivalent or better than theophylline. |

| Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD) | Oxygen dependency at 36 weeks postmenstrual age. | Adjusted OR for BPD occurrence (CAP trial) [8]. | CAP trial: OR = 0.63 (95% CI 0.52–0.76; p < 0.001) for BPD in caffeine vs. placebo (36.3% vs. 46.9%). Early caffeine administration associated with reduced BPD incidence in meta-analyses [63]. |

| Mechanical Ventilation Duration | Duration (hours/days) of invasive ventilation or non-invasive support (CPAP, NCPAP). | Mean difference or median difference in ventilation days between caffeine vs. control [8,34,47]. | Caffeine group had ≈1-week earlier discontinuation of positive pressure support (CAP trial). Theophylline reduced ventilation duration by ~33 h [34]. Early caffeine: shortened intubation and CPAP times [47]. |

| Extubation Success | Successful discontinuation of ventilation without reintubation within 48–72 h. | Proportion (%) success or RR. | Extubation success 78% vs. 53% with aminophylline [64]. Early caffeine improved extubation outcomes (lower FiO2, lower PIP) [47]. Pooled qualitative synthesis—consistent improvement in extubation success with methylxanthines. |

| Intermittent Hypoxemia (IH) | Events with ≥10% SpO2 drop from baseline per hour. | Rate ratio (events/hour) or mean difference. | Caffeine 10–20 mg/kg/day reduced IH frequency significantly vs. placebo. Rate ratio ~0.65 vs. placebo [56]. |

| Mortality | All-cause mortality during hospitalization or follow-up. | RR where reported (CAP trial). | No significant difference in mortality between caffeine and placebo (CAP trial; RR ≈ 1.0). |

| Neurodevelopmental Outcomes | Cognitive delay, cerebral palsy, deafness, blindness at 18–21 months or later. | Composite OR for adverse neurodevelopment (CAP trial), Mean z-scores for FEV1, IQ at 11 years [49]. | CAP trial follow-up (18–21 months): no increase in adverse outcomes; long-term follow-up showed better pulmonary function (FEV1 z-score −1.00 vs. −1.53) and trend to improved cognitive scores [65]. |

| Adverse Effects (Tachycardia, GI, Neurological) | Incidence of side effects requiring dose reduction or discontinuation. | Proportion (%) affected. | CAP trial: 1.8% required dose reduction (tachycardia/jitteriness). Tachycardia 8.3% (caffeine) vs. 34.4% (aminophylline/theophylline). Mild GI effects; no serious neurological toxicity [55]. |

| Growth Parameters | Weight gain and head circumference change over treatment. | Mean difference (grams). | CAP trial: temporary ↓ weight gain (−23 g at week 2), normalized by week 6. No difference in head growth. |

| Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) Closure | Need for pharmacologic/surgical PDA treatment. | Proportion (%) receiving PDA therapy. | CAP post hoc: significantly fewer infants required PDA closure in caffeine group. OR ≈ 0.68 (p < 0.05). |

| Length of Hospital Stay | Days from randomization to discharge. | Median difference (days). | No significant difference in length of stay (median 18 vs. 16.5 days) [60]. |

| No. | Study (Author, Year) | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Primary Outcome(s) | Key Findings | Risk-of-Bias Rating (Low/Some Concerns/High) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Aranda et al. (1983) [39] | Non-controlled study | 18 preterm neonates with recurrent apneic spells; mean birth weight: 1065.0 g; mean gestational age: 27.5 weeks. | Caffeine citrate, loading dose of 20 mg/kg intravenously, followed by a maintenance dose of 5 to 10 mg/kg once daily. | No comparator/control group; this was a non-controlled study. | Frequency of apneic episodes. | Caffeine significantly reduced mean apnea episodes (13.6 → 2.1/day) and improved ventilation parameters. | Some concerns |

| 2. | Gupta et al. (1981) [40] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 29 premature infants (15 in theophylline group, 14 in placebo group) with 4 or more apnoeas in a 12 h period. | Theophylline, initially 4 mg/kg six-hourly via nasogastric tube, increased to 6 mg/kg if no clinical response. | Placebo-same base as theophylline. | Decrease in the number of apneic episodes within 6–12 h of commencement of therapy. | Theophylline reduced apnea frequency within 6–12 h; 10/15 infants had no further episodes within 48 h. | Some concerns |

| 3. | Murat et al. (1981) [41] | Prospective controlled study | Eighteen preterm infants (29 to 35 weeks’ gestation). | Caffeine sodium citrate (20 mg/kg loading dose, 5 mg/kg daily maintenance dose). | Control group (no treatment, but received caffeine if condition worsened). | Change in frequency and severity of mild and severe apnea events. | Caffeine decreased both severe and mild apnea vs. control; no treatment failures occurred. | High |

| 4. | Greenough et al. (1985) [34] | Double-blind randomized trial | 40 preterm, ventilated infants (gestational ages 24–33 weeks, mean gestational age 29.8 ± 2.4 weeks in theophylline group. | Oral theophylline solution (5 mg/mL); loading dose: 1 mL/kg (5 mg/kg theophylline); maintenance dose: 1 mL/kg per day. | Placebo (vehicle alone) solution, administered orally via nasogastric tube. | Lung compliance and duration of mechanical ventilation. | Theophylline improved lung compliance and shortened ventilation duration compared to placebo. | Low |

| 5. | Bairam et al. (1987) [42] | Double-blind randomized controlled trial | 20 premature infants with idiopathic apnea; theophylline group (n = 10): birth weight 1.5 ± 0.3 kg. | Theophylline: loading dose 6 mg/kg, maintenance dose 2 mg/kg every 12 h administered intravenously. | Caffeine: loading dose 10 mg/kg, maintenance dose 1.25 mg/kg every 12 h, administered intravenously. | Frequency of apnea ≥ 15 s with bradycardia < 80 bpm in idiopathic AOP. | Both theophylline and caffeine decreased cardiorespiratory abnormalities; theophylline caused more side effects. | Some concerns |

| 6. | Bucher et al. (1988) [43] | Randomized controlled trial | 50 spontaneously breathing, preterm infants of 32 weeks’ gestation or less. | Caffeine citrate (loading dose 20 mg/kg, maintenance dose 10 mg/kg per day). | Placebo (NaCl 0.9%) | Proportion of infants with recurrent hypoxaemic episodes (>20% fall in SpO2). | Caffeine reduced recurrent hypoxemic episodes compared with placebo from 57% to 51%, though effect size was modest. | Some concerns |

| 7. | Erenberg, et al. (2000) [44] | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with an open-label rescue phase | 82 preterm infants (28 to 32 weeks post conceptual age) with >6 apnea episodes >20 s per 24 h. | Caffeine citrate: IV loading dose of 10 mg/kg with daily dose of 2.5 mg/kg caffeine base, followed by 3 mg/kg daily. | Placebo | Reduction ≥ 50% in apnea frequency. | ≥50% reduction in apnea achieved in 68.9% of caffeine group vs. placebo; consistent improvement over 10 days. | Some concerns |

| 8. | Schmidt et al. (2006) [8] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, No. NCT00182312/22.03.2018 | 2006 preterm infants with birth weights 500–1250 g, enrolled within first 10 days of life | Caffeine citrate: loading dose 20 mg/kg IV, maintenance 5 mg/kg daily (increased to 10 mg/kg if needed) until apnea resolved. | Placebo (normal saline) | Composite of death cerebral palsy, cognitive delay, deafness, or blindness at 18–21 months; secondary—BPD and short-term morbidities. | Caffeine reduced BPD (36% vs. 47%; OR 0.63, p < 0.001), shortened ventilation by ~1 week, and lowered PDA treatment rates; no significant differences in mortality, NEC, or brain injury. | Low |

| 9. | Jeong et al. (2015) [45] | Retrospective study | 143 infants born at less than 33 weeks of gestation (Caffeine group: n = 54, Theophylline group: n = 89). | Caffeine group (n = 54): loading dose of 20 mg/kg intravenously for 30 min, followed by 5–8 mg/kg intravenously once a day. | Theophylline group (n = 89): loading dose of 5–7 mg/kg intravenously for 30 min, followed by 1.5–2 mg/kg every 8 h. | Apnea frequency, adverse effects, and major neonatal morbidity (e.g., BPD, PVL). | Caffeine and theophylline showed similar short-term efficacy for apnea control. | Moderate |

| 10. | Armanian et al. (2016) [46] | Single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial (IRCT.ir (No. IRCT2013110610026N3). | 52 premature infants with a birth weight of ≤ 1200 g and spontaneous breathing at 24 h of life. | Caffeine administered intravenously; a loading dose of 20 mg/kg was given on the first day of life, followed by a daily maintenance dose. | Placebo group (n = 26) received an equivalent volume of normal saline daily for the first 10 days of life. | Incidence of apnea, bradycardia, and cyanosis during the first 10 days of life. | Caffeine prophylaxis lowered apnea incidence (15% vs. 62%) and reduced bradycardia events. | Some concerns |

| 11. | Wei et al. (2016) [47] | Prospective controlled clinical trial | 59 preterm infants with RDS requiring mechanical ventilation; gestational age 27–33 + 6 weeks, birth weight < 1500 g. | Caffeine (citrate) intravenously; caffeine group: 20 mg/kg loading dose at 12–24 h after birth, followed by 8 mg/kg daily maintenance dose. | Control group (n = 29) received caffeine 4–6 h before planned extubation (same dosage as caffeine group). | Respirator parameters (PIP, PEEP, FiO2, intubation time, NCPAP time, oxygen time), incidence of complications. | Early caffeine reduced ventilator pressures, oxygen needs, and ventilator-associated pneumonia incidence. | Some concerns |

| 12. | Dekker (2017) [48] | Randomized controlled trial | 30 preterm infants (23 analyzed) of 24–30 weeks’ gestation; birth weight was 870 g in the caffeine group and 960 g the comparison group. | A loading dose of caffeine base (10 mg/kg) administered in the delivery room within the first 7 min after birth. | Infants who received a loading dose of caffeine base (10 mg/kg) later, after arrival in the NICU. | Respiratory effort—minute and tidal volumes during initial ventilation. | Delivery-room caffeine improved minute (189 vs. 162 mL/kg/min) and tidal volumes (5.2 vs. 4.4 mL/kg) during initial neonatal ventilation. | High |

| 13. | Doyle et al. (2017) [49] | RCT–follow-up of the CAP trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, No. NCT00182312/22.03.2018) | 142 children (74 caffeine, 68 placebo) from the CAP trial, born with birth weight less than 1251 g (range 500–1250 g). | Caffeine citrate 20 mg/kg loading dose and 5–10 mg/kg/d maintenance dose. | Placebo (saline) | Pulmonary function at 11 years (FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, FEF25–75). | Former caffeine-treated infants had better expiratory flow rates (FEV1 z –1.00 vs. –1.53) at 11 years. | Some concerns |

| 14. | Habibi et al. (2019) [50] | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | 67 premature neonates with idiopathic apnea of prematurity; inclusion criteria: gestational age < 37 weeks. | Aminophylline: intravenous, 5–7 mg/kg loading dose, then 1–2 mg/kg every 6–12 h. Caffeine: intravenous, 20 mg/kg loading dose and 5–10 mg/kg/d maintenance dose. | Caffeine recipient group (n = 36). | Recurrent apnea frequency and short-term drug side effects. | Aminophylline and caffeine had similar efficacy and side-effect profiles; minimal recurrence of apnea. | Some concerns |

| 15. | Lookzadeh et al. (2019) [51] | Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) (IR code IRU.MEDICINE.REC.1397.78) | 80 premature neonates (43 male, 37 female) with gestational age under 34 weeks. | Caffeine (initial dose of 30 mg/kg, 24 h maintenance dose of 10 mg/kg). | Aminophylline (initial dose of 5 mg/kg, maintenance dose of 2 mg/kg every 8 h). | Apnea frequency, oxygen/CPAP requirement, and adverse events. | No significant difference in the frequency of apnea or oxygen need between the two groups. | Some concerns |

| 16. | Zulqarna et al. (2019) [52] | Randomized Control Trial | 100 infants (50 in Theophylline group, 50 in Caffeine group). | Theophylline: loading dose 4.8 mg/kg intravenously in 30 min, maintenance dose 2 mg/kg. | Theophylline group compared to Caffeine group. | Daily apnea episodes and correlation with methylxanthine serum levels. | Daily apnea rates improved after caffeine treatment compared with theophylline. | Some concerns |

| 17. | Fakoor et al. (2019) [53] | Clinical–experimental trial | 100 very preterm infants with a gestational age ≤ 32 weeks and a birthweight ≤ 1500 g. | Group A (50 infants) received 20 mg/kg of venous caffeine on the 2nd day of birth (24–48 h), followed by a maintenance. | Group B (50 infants) did not receive caffeine. | Prevention of apnea episodes in very preterm infants. | There was no significant difference in the incidence of apnea between the caffeine group (14%) and the control group (18%). | Some concerns |

| 18. | Liu et al. (2020) [54] | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Total of 194 preterm infants (≤32 weeks’ gestational age) initially; 160 infants included in final analysis. | Caffeine, administered within 72 h after birth. | Placebo group (n = 93) | White-matter maturation and apnea/ventilation duration. | Caffeine reduced apnea and ventilation duration and improved white-matter development on MRI. | Some concerns |

| 19. | Lin et al. (2022) [55] | Retrospective case–control gestational age-matched study | 144 premature infants (48 in caffeine group, 96 in aminophylline/theophylline group). | Caffeine: loading dose 20 mg/kg, maintenance 5 mg/kg/dose once per day, titrated by 10 mg/kg/dose per day. | Aminophylline/Theophylline group | Treatment duration and incidence of tachycardia (≥160 bpm). | Caffeine required shorter treatment (11 vs. 17 days) and caused less tachycardia (8% vs. 34%). | Some concerns |

| 20. | Iranpour (2022) [61] | Randomized Controlled Trial | 90 neonates (birth weight between 1250 and 2000 g) clinically diagnosed with RDS. | Caffeine: 20 mg/kg initial dose, then 10 mg/kg daily maintenance dose. | Control group (no placebo or similar drugs). | Duration of NCPAP respiratory support. | Caffeine shortened NCPAP duration (41 h vs. 78 h) compared with control. | Some concerns |

| 21. | Oliphant (2023) [56] | Phase IIB, double-blind, five-arm, parallel, randomized controlled trial. (anzctr.org.au, no. ACTRN12618001745235/24.10.2018 | 132 late preterm infants born at 34 + 0–36 + 6 weeks’ gestation, with a mean (SD) birth weight of 2561 (481) g. | Caffeine citrate: infants were randomly assigned to receive a loading dose (10, 20, 30 or 40 mg/kg) followed by a daily maintenance dose. | Placebo group receiving an equivolume enteral solution. | Rate of intermittent hypoxemia events per hour. | Caffeine 10–20 mg/kg/day reduced IH events vs. placebo. | Some concerns |

| 22. | Anggrainy (2024) [57] | Randomized clinical trial | Fifty premature neonates (gestational age 28–34 weeks, birth weight < 2500 g) with apnea of prematurity (AOP). | Oral caffeine citrate with an initial dose of 20 mg/kg BW, followed by a maintenance dose of 5–10 mg/kg BW/day. | Oral theophylline with an initial dose of 5–8 mg/kg, followed by 4–22 mg/kg BW every 6–8 h for seven days. | Mean daily apnea frequency after treatment. | Theophylline slightly reduced apnea episodes more than caffeine (3.16 vs. 2.28), but with longer CPAP use. | Some concerns |

| 23. | Bashar (2024) [58] | Prospective, open-label, randomized controlled trial | 55 preterm neonates (≤34 weeks’ gestational age); mean gestational age: 31.3 ± 2.1 weeks (range 26–34 weeks). | Caffeine (loading dose of 20 mg/kg, followed by maintenance doses of 5 mg/kg/day). | Aminophylline (loading dose of 5 mg/kg, followed by maintenance doses of 2 mg/kg every 8 h). | Comparative efficacy and safety of caffeine vs. aminophylline for AOP prophylaxis/treatment. | Caffeine and aminophylline had similar efficacy and safety; no major outcome differences. | High |

| 24. | Raza (2024) [59] | Comparative randomized study | A total of 60 premature newborn babies (<37 weeks’ gestation) with their first apnea episode. | Caffeine (intravenous, 20 mg/kg anhydrous caffeine loading dose, 5 mg/kg maintenance every 24 h). | Aminophylline (intravenous, 5 mg/kg loading dose, 1.5 mg/kg maintenance every 12 h). | Reappearance of apnea within ≥3 days after initial episode. | Caffeine showed higher efficacy (87% vs. 63%), less oxygen need, and fewer reintubations than aminophylline. | High |

| 25. | Carlo (2025) [60] | Randomized clinical trial (Clinicaltrials.gov, no. NCT03340727) | 827 infants born at 29 to 33 weeks’ gestation (median gestational age, 31 weeks; 414 female [51%]). | Oral caffeine citrate 10 mg/kg/day | Placebo | Time to hospital discharge after randomization. | Extended caffeine therapy did not reduce hospital stay (18 vs. 16.5 days). | Low |

| Characteristic | Caffeine | Theophylline |

|---|---|---|

| Half-life | Longer half-life | Shorter half-life |

| Dosing Frequency | Once-daily dosing | More frequent dosing required |

| Therapeutic Window | Wider therapeutic window with reduced toxicity risk | Narrower therapeutic window |

| Pharmacokinetic Predictability | More predictable pharmacokinetics in preterm infants | More complex metabolism with age-related changes |

| Drug Interactions | Minimal drug interactions | Greater potential for drug interactions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neamțu, A.-V.; Zlatian, O.M.; Manda, C.-V.; Cioboată, R.; Bărbulescu-Mateescu, C.-M.; Coteanu, C.; Chiuțu, L.-C.; Stanca, L.; Mateescu, O.G.; Neamțu, S.-D. Methylxanthines: The Major Impact of Caffeine in Clinical Practice in Patients Diagnosed with Apnea of Prematurity. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8417. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238417

Neamțu A-V, Zlatian OM, Manda C-V, Cioboată R, Bărbulescu-Mateescu C-M, Coteanu C, Chiuțu L-C, Stanca L, Mateescu OG, Neamțu S-D. Methylxanthines: The Major Impact of Caffeine in Clinical Practice in Patients Diagnosed with Apnea of Prematurity. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8417. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238417

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeamțu, Adela-Valeria, Ovidiu Mircea Zlatian, Costel-Valentin Manda, Ramona Cioboată, Carla-Maria Bărbulescu-Mateescu, Cătălina Coteanu, Luminița-Cristina Chiuțu, Liliana Stanca, Olivia Garofița Mateescu, and Simona-Daniela Neamțu. 2025. "Methylxanthines: The Major Impact of Caffeine in Clinical Practice in Patients Diagnosed with Apnea of Prematurity" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8417. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238417

APA StyleNeamțu, A.-V., Zlatian, O. M., Manda, C.-V., Cioboată, R., Bărbulescu-Mateescu, C.-M., Coteanu, C., Chiuțu, L.-C., Stanca, L., Mateescu, O. G., & Neamțu, S.-D. (2025). Methylxanthines: The Major Impact of Caffeine in Clinical Practice in Patients Diagnosed with Apnea of Prematurity. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8417. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238417