First Breath Matters: Out-of-Hospital Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Cerebral Autoregulation in TBI

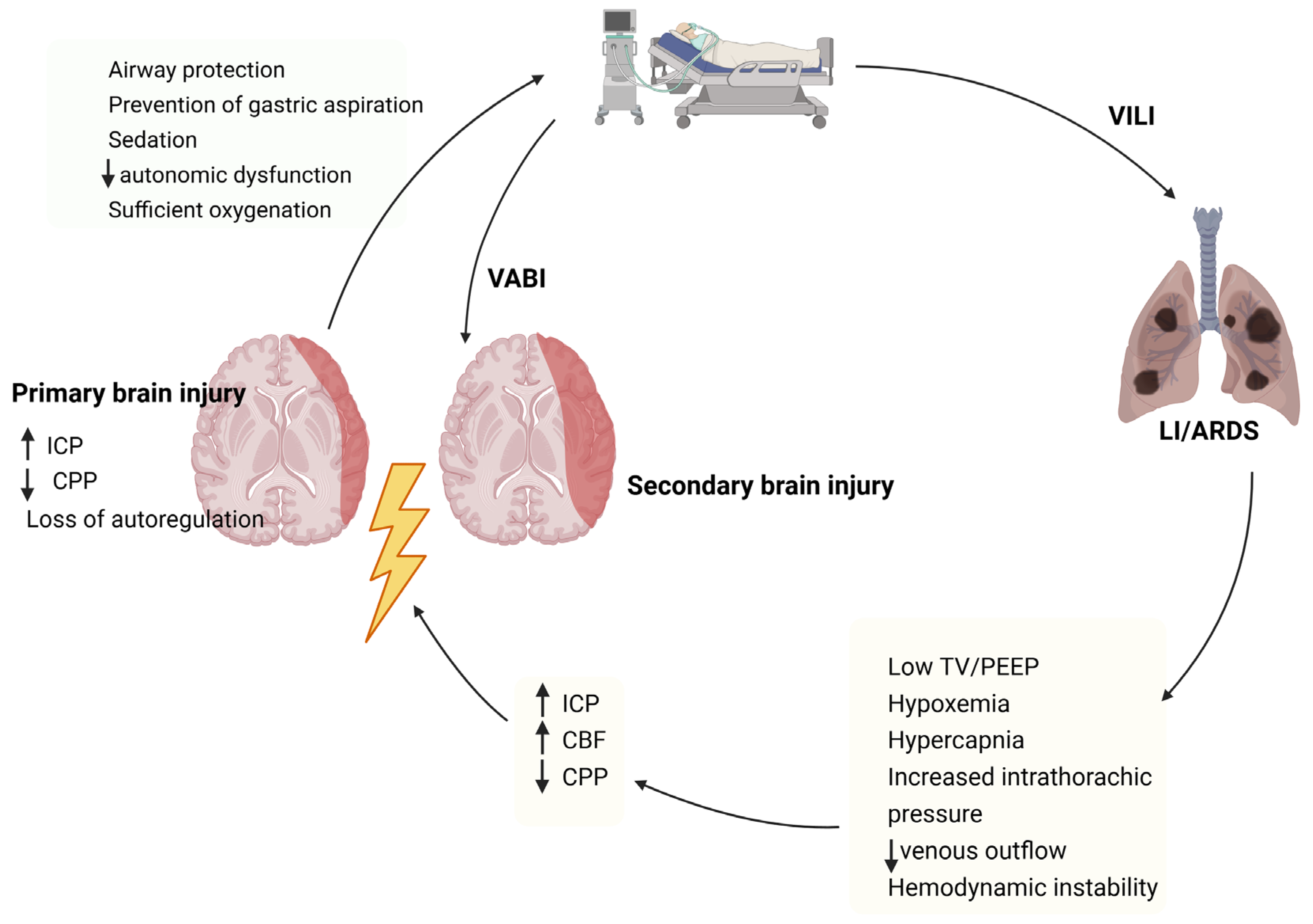

4. Gas Exchange Alterations and Cerebral Homeostasis in Traumatic Brain Injury

5. Effects of Mechanical Ventilation on Cerebral Autoregulation

6. Ventilatory Strategies in TBI

7. Goals of PaO2 and PaCO2

8. Tidal Volume

9. Positive End-Expiratory Pressure

10. Areas of Future Research

11. Limitations of the Existing Evidence

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khellaf, A.; Khan, D.Z.; Helmy, A. Recent advances in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 2878–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Sharma, S. Recent Advances in Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeev, I.; Santarius, T.; Kolias, A.G.; Hutchinson, P.J. Decompressive craniectomy-operative technique and perioperative care. Adv. Tech. Stand. Neurosurg. 2012, 38, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; Adelson, P.D.; Andelic, N.; Bell, M.J.; Belli, A.; Bragge, P.; Brazinova, A.; Buki, A.; Chesnut, R.M.; et al. Traumatic brain injury: Integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 987–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, D.A.; Murillo-Cabezas, F.; Suarez, J.I.; Badenes, R.; Pelosi, P.; Robba, C. “THE MANTLE” bundle for minimizing cerebral hypoxia in severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, A.; Zhang, J.H.; Obenaus, A. Response of the cerebral vasculature following traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2017, 37, 2320–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauner, A.; Daugherty, W.P.; Bullock, M.R.; Warner, D.S. Brain oxygenation and energy metabolism: Part I-biological function and pathophysiology. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, 289–301; discussion 302. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, G.S.; Engel, D.C.; Butcher, I.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Lu, J.; Mushkudiani, N.; Hernandez, A.V.; Marmarou, A.; Maas, A.I.; Murray, G.D. Prognostic value of secondary insults in traumatic brain injury: Results from the IMPACT study. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Taccone, F.S.; He, X. Harmful Effects of Hyperoxia in Postcardiac Arrest, Sepsis, Traumatic Brain Injury, or Stroke: The Importance of Individualized Oxygen Therapy in Critically Ill Patients. Can. Respir. J. 2017, 2017, 2834956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, E.; Peelen, L.; Keijzers, P.J.; Joore, H.; de Lange, D.; van der Voort, P.H.; Bosman, R.J.; de Waal, R.A.; Wesselink, R.; de Keizer, N.F. Association between administered oxygen, arterial partial oxygen pressure and mortality in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care 2008, 12, R156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusin, G.; Farley, C.; Dorris, C.S.; Yusina, S.; Zaatari, S.; Goyal, M. The Effect of Early Severe Hyperoxia in Adults Intubated in the Prehosptial Setting or Emergency Department: A Scoping Review. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 65, e495–e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Poole, D.; McNett, M.; Asehnoune, K.; Bösel, J.; Bruder, N.; Chieregato, A.; Cinotti, R.; Duranteau, J.; Einav, S.; et al. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute brain injury: Recommendations of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine consensus. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 2397–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arleth, T.; Baekgaard, J.; Rosenkrantz, O.; Zwisler, S.T.; Andersen, M.; Maissan, I.M.; Hautz, W.E.; Verdonck, P.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Steinmetz, J. Clinicians’ attitudes towards supplemental oxygen for trauma patients-A survey. Injury 2025, 56, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iten, M.; Pietsch, U.; Knapp, J.; Jakob, D.A.; Krummrey, G.; Maschmann, C.; Steinmetz, J.; Arleth, T.; Mueller, M.; Hautz, W. Hyperoxaemia in acute trauma is common and associated with a longer hospital stay: A multicentre retrospective cohort study. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2024, 32, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Brain-lung interactions and mechanical ventilation in patients with isolated brain injury. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascia, L.; Andrews, P.J. Acute lung injury in head trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 1998, 24, 1115–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, A.D.T.; Ranieri, V.M.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Thompson, B.T.; Ferguson, N.D.; Caldwell, E.; Fan, E.; Camporota, L.; Slutsky, A.S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012, 307, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonis, F.D.; Serpa Neto, A.; Binnekade, J.M.; Braber, A.; Bruin, K.C.M.; Determann, R.M.; Goekoop, G.J.; Heidt, J.; Horn, J.; Innemee, G.; et al. Effect of a Low vs Intermediate Tidal Volume Strategy on Ventilator-Free Days in Intensive Care Unit Patients Without ARDS: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, V.; Badenes, R.; Corradi, F.; Racca, F.; Lavinio, A.; Matta, B.; Bilotta, F.; Robba, C. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in traumatic brain injury: How do we manage it? J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 5368–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropper, A.H. Hyperosmolar therapy for raised intracranial pressure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Pathophysiology of acute lung injury in patients with acute brain injury: The triple-hit hypothesis. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Siwicka-Gieroba, D.; Sikter, A.; Battaglini, D.; Dabrowski, W.; Schultz, M.J.; de Jonge, E.; Grim, C.; Rocco, P.R.; Pelosi, P. Pathophysiology and clinical consequences of arterial blood gases and pH after cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, M.; Citerio, G. ARDS in the brain-injured patient: What’s different? Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, U.; Muller, M.; Hautz, W.E.; Jakob, D.A.; Knapp, J. The Importance of Normocapnia in Patients With Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Prehospital Emergency Medicine. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2025, 6, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teismann, I.K.; Oelschläger, C.; Werstler, N.; Korsukewitz, C.; Minnerup, J.; Ringelstein, E.B.; Dziewas, R. Discontinuous versus Continuous Weaning in Stroke Patients. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2015, 39, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilotta, F.; Robba, C.; Santoro, A.; Delfini, R.; Rosa, G.; Agati, L. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Imaging in Detection of Changes in Cerebral Perfusion. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 42, 2708–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinotti, R.; Bouras, M.; Roquilly, A.; Asehnoune, K. Management and weaning from mechanical ventilation in neurologic patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woratyla, S.P.; Morgan, A.S.; Mackay, L.; Bernstein, B.; Barba, C. Factors associated with early onset pneumonia in the severely brain-injured patient. Conn. Med. 1995, 59, 643–647. [Google Scholar]

- Bronchard, R.; Albaladejo, P.; Brezac, G.; Geffroy, A.; Seince, P.F.; Morris, W.; Branger, C.; Marty, J. Early onset pneumonia: Risk factors and consequences in head trauma patients. Anesthesiology 2004, 100, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.J.; Siegler, J.E.; Fuller, B.M. Mechanical Ventilation in the Prehospital and Emergency Department Environment. Respir. Care 2019, 64, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, J.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Panerai, R.B.; Faraci, F.M. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: Physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1487–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, N.A. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol. Rev. 1959, 39, 183–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Hautz, W.; Exadaktylos, A. A Comprehensive Review of Fluid Resuscitation Strategies in Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.O.; Adji, A.; O’Rourke, M.F.; Avolio, A.P.; Smielewski, P.; Pickard, J.D.; Czosnyka, M. Principles of cerebral hemodynamics when intracranial pressure is raised: Lessons from the peripheral circulation. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, N.A. The Monro-Kellie doctrine in its own context. J. Neurosurg. 2025, 142, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, J.C. The lower limit of autoregulation: Time to revise our thinking? Anesthesiology 1997, 86, 1431–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoemaker, L.N.; Milej, D.; Sajid, A.; Mistry, J.; Lawrence, K.S.; Shoemaker, J.K. Characterization of cerebral macro- and microvascular hemodynamics during transient hypotension. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2023, 135, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.A.; Carpenter, K.L.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Smielewski, P.; Helmy, A. Candidate neuroinflammatory markers of cerebral autoregulation dysfunction in human acute brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2023, 43, 1237–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osol, G.; Halpern, W. Myogenic properties of cerebral blood vessels from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1985, 249, H914–H921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.O.; Hamner, J.W.; Taylor, J.A. The role of myogenic mechanisms in human cerebrovascular regulation. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 5095–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godo, S.; Shimokawa, H. Endothelial Functions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, e108–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.C.; Wang, Z.; Britz, G. Regulation of cerebral blood flow. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2011, 2011, 823525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.A. The role of nitric oxide and other endothelium-derived vasoactive substances in vascular disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1995, 38, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szenasi, A.; Amrein, K.; Czeiter, E.; Szarka, N.; Toth, P.; Koller, A. Molecular Pathomechanisms of Impaired Flow-Induced Constriction of Cerebral Arteries Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Potential Impact on Cerebral Autoregulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willie, C.K.; Tzeng, Y.C.; Fisher, J.A.; Ainslie, P.N. Integrative regulation of human brain blood flow. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, P.M.; Heistad, D.D.; Strait, M.R.; Marcus, M.L.; Brody, M.J. Cerebral vascular responses to physiological stimulation of sympathetic pathways in cats. Circ. Res. 1979, 44, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, P.N.; Brassard, P. Why is the neural control of cerebral autoregulation so controversial? F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassard, P.; Labrecque, L.; Smirl, J.D.; Tymko, M.M.; Caldwell, H.G.; Hoiland, R.L.; Lucas, S.J.E.; Denault, A.Y.; Couture, E.J.; Ainslie, P.N. Losing the dogmatic view of cerebral autoregulation. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.P.; De Sloovere, V.; Meyfroidt, G.; Depreitere, B. Differential Hemodynamic Response of Pial Arterioles Contributes to a Quadriphasic Cerebral Autoregulation Physiology. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e022943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, F.A.; Aries, M.; Czosnyka, M.; Smielewski, P. Cerebral Autoregulation Monitoring in Traumatic Brain Injury: An Overview of Recent Advances in Personalized Medicine. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, F.; Zeiler, F.A.; Ercole, A.; Monteiro, M.; Kamnitsas, K.; Glocker, B.; Whitehouse, D.P.; Das, T.; Smielewski, P.; Czosnyka, M.; et al. Relationship between Measures of Cerebrovascular Reactivity and Intracranial Lesion Progression in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: A CENTER-TBI Study. J. Neurotrauma 2020, 37, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junger, E.C.; Newell, D.W.; Grant, G.A.; Avellino, A.M.; Ghatan, S.; Douville, C.M.; Lam, A.M.; Aaslid, R.; Winn, H.R. Cerebral autoregulation following minor head injury. J. Neurosurg. 1997, 86, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, D.; Taran, S.; Bolaki, M.; Akoumianaki, E. Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Acute Brain Injuries: A Pathophysiology-based Approach. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, S.; Patriota, G.C.; Godoy, D.A.; Paranhos, J.L.; Rubiano, A.M.; Paiva, W.S. Monro-Kellie 4.0: Moving from intracranial pressure to intracranial dynamics. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.M.; Glass, H.I. Effect of alterations in the arterial carbon dioxide tension on the blood flow through the cerebral cortex at normal and low arterial blood pressures. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1965, 28, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, D.A.; Badenes, R.; Robba, C.; Murillo Cabezas, F. Hyperventilation in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Has Something Changed in the Last Decade or Uncertainty Continues? A Brief Review. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 573237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brian, J.E., Jr. Carbon dioxide and the cerebral circulation. Anesthesiology 1998, 88, 1365–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouvea Bogossian, E.; Peluso, L.; Creteur, J.; Taccone, F.S. Hyperventilation in Adult TBI Patients: How to Approach It? Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 580859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, D.A.; Seifi, A.; Garza, D.; Lubillo-Montenegro, S.; Murillo-Cabezas, F. Hyperventilation Therapy for Control of Posttraumatic Intracranial Hypertension. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchetti, N.; Maas, A.I.; Chieregato, A.; van der Plas, A.A. Hyperventilation in head injury: A review. Chest 2005, 127, 1812–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.P.; Minhas, P.S.; Fryer, T.D.; Smielewski, P.; Aigbirihio, F.; Donovan, T.; Downey, S.P.; Williams, G.; Chatfield, D.; Matthews, J.C.; et al. Effect of hyperventilation on cerebral blood flow in traumatic head injury: Clinical relevance and monitoring correlates. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diringer, M.N.; Videen, T.O.; Yundt, K.; Zazulia, A.R.; Aiyagari, V.; Dacey, R.G., Jr.; Grubb, R.L.; Powers, W.J. Regional cerebrovascular and metabolic effects of hyperventilation after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2002, 96, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citerio, G.; Robba, C.; Rebora, P.; Petrosino, M.; Rossi, E.; Malgeri, L.; Stocchetti, N.; Galimberti, S.; Menon, D.K. Management of arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the first week after traumatic brain injury: Results from the CENTER-TBI study. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandi, G.; Stocchetti, N.; Pagnamenta, A.; Stretti, F.; Steiger, P.; Klinzing, S. Cerebral metabolism is not affected by moderate hyperventilation in patients with traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Zhang, X.; Ou, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, S.; Zeng, H.; Jiang, W.; Wen, M. Optimal Targets of the First 24-h Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide in Patients with Cerebral Injury: Data from the MIMIC-III and IV Database. Neurocrit Care 2022, 36, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asehnoune, K.; Rooze, P.; Robba, C.; Bouras, M.; Mascia, L.; Cinotti, R.; Pelosi, P.; Roquilly, A. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute brain injury: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.G.; Eastwood, G.M.; Bellomo, R.; Bailey, M.; Lipcsey, M.; Pilcher, D.; Young, P.; Stow, P.; Santamaria, J.; Stachowski, E.; et al. Arterial carbon dioxide tension and outcome in patients admitted to the intensive care unit after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2013, 84, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaahersalo, J.; Bendel, S.; Reinikainen, M.; Kurola, J.; Tiainen, M.; Raj, R.; Pettila, V.; Varpula, T.; Skrifvars, M.B.; Group, F.S. Arterial blood gas tensions after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Associations with long-term neurologic outcome. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, G.M.; Tanaka, A.; Bellomo, R. Cerebral oxygenation in mechanically ventilated early cardiac arrest survivors: The impact of hypercapnia. Resuscitation 2016, 102, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolner, E.A.; Hochman, D.W.; Hassinen, P.; Otahal, J.; Gaily, E.; Haglund, M.M.; Kubova, H.; Schuchmann, S.; Vanhatalo, S.; Kaila, K. Five percent CO(2) is a potent, fast-acting inhalation anticonvulsant. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Croinin, D.; Ni Chonghaile, M.; Higgins, B.; Laffey, J.G. Bench-to-bedside review: Permissive hypercapnia. Crit. Care 2005, 9, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Battaglini, D.; Abbas, A.; Sarrio, E.; Cinotti, R.; Asehnoune, K.; Taccone, F.S.; Rocco, P.R.; Schultz, M.J.; Citerio, G.; et al. Clinical practice and effect of carbon dioxide on outcomes in mechanically ventilated acute brain-injured patients: A secondary analysis of the ENIO study. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinotti, R.; Mijangos, J.C.; Pelosi, P.; Haenggi, M.; Gurjar, M.; Schultz, M.J.; Kaye, C.; Godoy, D.A.; Alvarez, P.; Ioakeimidou, A.; et al. Extubation in neurocritical care patients: The ENIO international prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, D.A.; Rovegno, M.; Lazaridis, C.; Badenes, R. The effects of arterial CO(2) on the injured brain: Two faces of the same coin. J. Crit. Care 2021, 61, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofke, W.A.; Rajagopalan, S.; Ayubcha, D.; Balu, R.; Cruz-Navarro, J.; Manatpon, P.; Mahanna-Gabrielli, E. Defining a Taxonomy of Intracranial Hypertension: Is ICP More Than Just a Number? J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2020, 32, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.R.; Wetmore, G.C.; Goodman, M.D.; Rodriquez, D., Jr.; Branson, R.D. Review of Ventilation in Traumatic Brain Injury. Respir. Care 2025, 70, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, S.; Cho, S.M.; Stevens, R.D. Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: Is it so Different? Neurocrit Care 2023, 38, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Exploring the lung-gut direction of the gut-lung axis in patients with ARDS. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, P.; Stevens, R.D.; Mirski, M.A. Neurologic injury and mechanical ventilation. Neurocrit Care 2008, 9, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, T.; Taran, S.; Girard, T.D.; Robba, C.; Goligher, E.C. Ventilator-associated Brain Injury: A New Priority for Research in Mechanical Ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 1186–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.L.; Rocco, P.R.M. The basics of respiratory mechanics: Ventilator-derived parameters. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iavarone, I.G.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Grieco, D.L.; Rosa, T.; Pellegrini, M.; Badenes, R.; Stevens, R.D.; Asehnoune, K.; Robba, C.; Camporota, L.; et al. Pathophysiology and clinical applications of PEEP in acute brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 2104–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beqiri, E.; Smielewski, P.; Guerin, C.; Czosnyka, M.; Robba, C.; Bjertnaes, L.; Frisvold, S.K. Neurological and respiratory effects of lung protective ventilation in acute brain injury patients without lung injury: Brain vent, a single centre randomized interventional study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, A.; Cardim, D.; Ciliberti, P.; Battaglini, D.; Ball, L.; Kasprowicz, M.; Beqiri, E.; Smielewski, P.; Czosnyka, M.; Frisvold, S.; et al. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on cerebral hemodynamics in acute brain injury patients. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1139658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammervold, R.; Beqiri, E.; Smielewski, P.; Storm, B.S.; Nielsen, E.W.; Guerin, C.; Frisvold, S.K. Positive end-expiratory pressure increases intracranial pressure but not pressure reactivity index in supine and prone positions: A porcine model study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1501284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Castilla, L.; Gasco, J.; Nauta, H.J.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Robertson, C.S. Cerebral pressure autoregulation in traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008, 25, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, G.J.; Muizelaar, J.P. Cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, and cerebrovascular reactivity after severe head injury. J. Neurotrauma 1992, 9 (Suppl. S1), S333–S348. [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi, P.; Ferguson, N.D.; Frutos-Vivar, F.; Anzueto, A.; Putensen, C.; Raymondos, K.; Apezteguia, C.; Desmery, P.; Hurtado, J.; Abroug, F.; et al. Management and outcome of mechanically ventilated neurologic patients. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, R.; Kawati, R.; Hanell, A.; Lewen, A.; Enblad, P.; Engquist, H.; Bjarnadottir, K.J.; Joensen, O.; Barrueta Tenhunen, A.; Freden, F.; et al. Intracranial response to positive end-expiratory pressure is influenced by lung recruitability and gas distribution during mechanical ventilation in acute brain injury patients: A proof-of-concept physiological study. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2025, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.H.; Knudson, M.M.; Vassar, M.J.; McCarthy, M.C.; Shapiro, M.B.; Mallet, S.; Holcroft, J.J.; Moncrief, H.; Noble, J.; Wisner, D.; et al. Prehospital hypoxia affects outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury: A prospective multicenter study. J. Trauma 2006, 61, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, G.D.; Butcher, I.; McHugh, G.S.; Lu, J.; Mushkudiani, N.A.; Maas, A.I.; Marmarou, A.; Steyerberg, E.W. Multivariable prognostic analysis in traumatic brain injury: Results from the IMPACT study. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, M.; Bodnar, D.; Williamson, F.; Parker, L.; Ryan, G. Prevalence of secondary insults and outcomes of patients with traumatic brain injury intubated in the prehospital setting: A retrospective cohort study. Emerg. Med. J. 2023, 40, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, L.; Fanelli, V.; Mistretta, A.; Filippini, M.; Zanin, M.; Berardino, M.; Mazzeo, A.T.; Caricato, A.; Antonelli, M.; Della Corte, F.; et al. Lung-Protective Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Severe Acute Brain Injury: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (PROLABI). Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muizelaar, J.P.; Marmarou, A.; Ward, J.D.; Kontos, H.A.; Choi, S.C.; Becker, D.P.; Gruemer, H.; Young, H.F. Adverse effects of prolonged hyperventilation in patients with severe head injury: A randomized clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. 1991, 75, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hulst, R.A.; Lameris, T.W.; Haitsma, J.J.; Klein, J.; Lachmann, B. Brain glucose and lactate levels during ventilator-induced hypo- and hypercapnia. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2004, 24, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttunen, J.; Tolvanen, H.; Heinonen, E.; Voipio, J.; Wikstrom, H.; Ilmoniemi, R.J.; Hari, R.; Kaila, K. Effects of voluntary hyperventilation on cortical sensory responses. Electroencephalographic and magnetoencephalographic studies. Exp. Brain Res. 1999, 125, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, D.W.; Puccio, A.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Kochanek, P.; Dixon, C.E.; Bullian, L.; Carlier, P. Effect of hyperventilation on extracellular concentrations of glutamate, lactate, pyruvate, and local cerebral blood flow in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 2619–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.P.; Hoyt, D.B.; Ochs, M.; Fortlage, D.; Holbrook, T.; Marshall, L.K.; Rosen, P. The effect of paramedic rapid sequence intubation on outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma 2003, 54, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, T.M.; Visioni, A.J.; Rughani, A.I.; Tranmer, B.I.; Crookes, B. Inappropriate prehospital ventilation in severe traumatic brain injury increases in-hospital mortality. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaite, D.W.; Bobrow, B.J.; Keim, S.M.; Barnhart, B.; Chikani, V.; Gaither, J.B.; Sherrill, D.; Denninghoff, K.R.; Mullins, T.; Adelson, P.D.; et al. Association of Statewide Implementation of the Prehospital Traumatic Brain Injury Treatment Guidelines With Patient Survival Following Traumatic Brain Injury: The Excellence in Prehospital Injury Care (EPIC) Study. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, e191152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulla, A.; Lumba-Brown, A.; Totten, A.M.; Maher, P.J.; Badjatia, N.; Bell, R.; Donayri, C.T.J.; Fallat, M.E.; Hawryluk, G.W.J.; Goldberg, S.A.; et al. Prehospital Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury-3rd Edition. Prehosp Emerg. Care 2023, 27, 507–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Vajpeyee, A.; Phadke, R.V.; Handique, A.; Salwani, V. Brain herniations in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2009, 119, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picetti, E.; Catena, F.; Abu-Zidan, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Armonda, R.A.; Bala, M.; Balogh, Z.J.; Bertuccio, A.; Biffl, W.L.; Bouzat, P.; et al. Early management of isolated severe traumatic brain injury patients in a hospital without neurosurgical capabilities: A consensus and clinical recommendations of the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES). World J. Emerg. Surg. 2023, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk, G.W.J.; Lulla, A.; Bell, R.; Jagoda, A.; Mangat, H.S.; Bobrow, B.J.; Ghajar, J. Guidelines for Prehospital Management of Traumatic Brain Injury 3rd Edition: Executive Summary. Neurosurgery 2023, 93, e159–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin-Jones, T.; Solorzano-Aldana, M.C.; Rezk, A.; Rizk, A.A.; Lele, A.V.; Englesakis, M.; Zeiler, F.A.; Chowdhury, T. Impact of oxygen and carbon dioxide levels on mortality in moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezoagli, E.; Petrosino, M.; Rebora, P.; Menon, D.K.; Mondello, S.; Cooper, D.J.; Maas, A.I.R.; Wiegers, E.J.A.; Galimberti, S.; Citerio, G.; et al. High arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration in traumatic brain injury: Insights from CENTER-TBI and OzENTER-TBI. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1709–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirunpattarasilp, C.; Shiina, H.; Na-Ek, N.; Attwell, D. The Effect of Hyperoxemia on Neurological Outcomes of Adult Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurocrit Care 2022, 36, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, P.; Keane, S.; Martin-Loeches, I. Change is in the air: Dying to breathe oxygen in acute respiratory distress syndrome? J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S2133–S2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfar, P.; Schortgen, F.; Boisrame-Helms, J.; Charpentier, J.; Guerot, E.; Megarbane, B.; Grimaldi, D.; Grelon, F.; Anguel, N.; Lasocki, S.; et al. Hyperoxia and hypertonic saline in patients with septic shock (HYPERS2S): A two-by-two factorial, multicentre, randomised, clinical trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.S.; Tenfen, L.; Joaquim, L.; Lanzzarin, E.V.R.; Bernardes, G.C.; Bonfante, S.R.; Mathias, K.; Biehl, E.; Bagio, E.; Stork, S.S.; et al. Hyperoxia by short-term promotes oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in rat brain. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2022, 306, 103963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hencz, A.J.; Magony, A.; Thomas, C.; Kovacs, K.; Szilagyi, G.; Pal, J.; Sik, A. Short-term hyperoxia-induced functional and morphological changes in rat hippocampus. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1376577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon Machado, R.; Mathias, K.; Joaquim, L.; de Quadros, R.W.; Rezin, G.T.; Petronilho, F. Hyperoxia and brain: The link between necessity and injury from a molecular perspective. Neurotox. Res. 2024, 42, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortet, G.; Ma, L.; Garcia-Medina, J.S.; LaManna, J.; Xu, K. Impaired Cognitive Performance in Mice Exposed to Prolonged Hyperoxia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1395, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arleth, T.; Baekgaard, J.; Siersma, V.; Creutzburg, A.; Dinesen, F.; Rosenkrantz, O.; Heiberg, J.; Isbye, D.; Mikkelsen, S.; Hansen, P.M.; et al. Early Restrictive vs Liberal Oxygen for Trauma Patients: The TRAUMOX2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Jacobs, A.; Brody, D.L.; Friess, S.H. Delayed Hypoxemia after Traumatic Brain Injury Exacerbates Long-Term Behavioral Deficits. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, D.A.; Rubiano, A.M.; Paranhos, J.; Robba, C.; Lazaridis, C. Avoiding brain hypoxia in severe traumatic brain injury in settings with limited resources-A pathophysiological guide. J. Crit. Care 2023, 75, 154260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesnut, R.M.; Marshall, L.F.; Klauber, M.R.; Blunt, B.A.; Baldwin, N.; Eisenberg, H.M.; Jane, J.A.; Marmarou, A.; Foulkes, M.A. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J. Trauma 1993, 34, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaite, D.W.; Hu, C.; Bobrow, B.J.; Chikani, V.; Barnhart, B.; Gaither, J.B.; Denninghoff, K.R.; Adelson, P.D.; Keim, S.M.; Viscusi, C.; et al. The Effect of Combined Out-of-Hospital Hypotension and Hypoxia on Mortality in Major Traumatic Brain Injury. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 69, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.P.; Idris, A.H.; Sise, M.J.; Kennedy, F.; Eastman, A.B.; Velky, T.; Vilke, G.M.; Hoyt, D.B. Early ventilation and outcome in patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirawattanasoot, N.; Chantanakomes, J.; Pansiritanachot, W.; Rangabpai, W.; Surabenjawong, U.; Chaisirin, W.; Riyapan, S.; Shin, S.D.; Song, K.J.; Chiang, W.C.; et al. Association between prehospital oxygen saturation and outcomes in hypotensive traumatic brain injury patients in Asia (Pan-Asian Trauma Outcomes Study (PATOS)). Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 18, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.P.; Meade, W.; Sise, M.J.; Kennedy, F.; Simon, F.; Tominaga, G.; Steele, J.; Coimbra, R. Both hypoxemia and extreme hyperoxemia may be detrimental in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2009, 26, 2217–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, E.; Del Sorbo, L.; Goligher, E.C.; Hodgson, C.L.; Munshi, L.; Walkey, A.J.; Adhikari, N.K.J.; Amato, M.B.P.; Branson, R.; Brower, R.G.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical Ventilation in Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sud, S.; Friedrich, J.O.; Adhikari, N.K.J.; Fan, E.; Ferguson, N.D.; Guyatt, G.; Meade, M.O. Comparative Effectiveness of Protective Ventilation Strategies for Moderate and Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. A Network Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpa Neto, A.; Cardoso, S.O.; Manetta, J.A.; Pereira, V.G.; Esposito, D.C.; Pasqualucci Mde, O.; Damasceno, M.C.; Schultz, M.J. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2012, 308, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slutsky, A.S.; Ranieri, V.M. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2126–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, J.; Libuy, J.; Jimenez, M.; Delgado, M.; Besa, C.; Bugedo, G.; Bruhn, A. Preliminary study of ventilation with 4 ml/kg tidal volume in acute respiratory distress syndrome: Feasibility and effects on cyclic recruitment-derecruitment and hyperinflation. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, L.; Zavala, E.; Bosma, K.; Pasero, D.; Decaroli, D.; Andrews, P.; Isnardi, D.; Davi, A.; Arguis, M.J.; Berardino, M.; et al. High tidal volume is associated with the development of acute lung injury after severe brain injury: An international observational study. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, A.; Payne, S. The conducted vascular response as a mediator of hypercapnic cerebrovascular reactivity: A modelling study. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 107985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderloni, M.; Schuind, S.; Salvagno, M.; Donadello, K.; Peluso, L.; Annoni, F.; Taccone, F.S.; Gouvea Bogossian, E. Brain Oxygenation Response to Hypercapnia in Patients with Acute Brain Injury. Neurocrit Care 2024, 40, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Zuccarello, M.; Rapoport, R.M. pCO(2) and pH regulation of cerebral blood flow. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daza, J.F.; Hamad, D.M.; Urner, M.; Liu, K.; Wahlster, S.; Robba, C.; Stevens, R.D.; McCredie, V.A.; Cinotti, R.; Taran, S.; et al. Low-Tidal-Volume Ventilation and Mortality in Patients With Acute Brain Injury: A Secondary Analysis of an International Observational Study. Chest 2025, 68, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asehnoune, K.; Mrozek, S.; Perrigault, P.F.; Seguin, P.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Lasocki, S.; Pujol, A.; Martin, M.; Chabanne, R.; Muller, L.; et al. A multi-faceted strategy to reduce ventilation-associated mortality in brain-injured patients. The BI-VILI project: A nationwide quality improvement project. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinotti, R.; Taran, S.; Stevens, R.D. Setting the ventilator in acute brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 1513–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukou, A.; Katsiari, M.; Orfanos, S.E.; Kotanidou, A.; Daganou, M.; Kyriakopoulou, M.; Koulouris, N.G.; Rovina, N. Respiratory mechanics in brain injury: A review. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 5, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Bonatti, G.; Pelosi, P.; Citerio, G. Extracranial complications after traumatic brain injury: Targeting the brain and the body. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2020, 26, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Bonatti, G.; Battaglini, D.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Pelosi, P. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute ischaemic stroke: From pathophysiology to clinical practice. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turon, M.; Fernández-Gonzalo, S.; de Haro, C.; Magrans, R.; López-Aguilar, J.; Blanch, L. Mechanisms involved in brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: Implications and therapeutics. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranieri, V.M.; Eissa, N.T.; Corbeil, C.; Chassé, M.; Braidy, J.; Matar, N.; Milic-Emili, J. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on alveolar recruitment and gas exchange in patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1991, 144, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, L.; Fernandez, R.; Benito, S.; Mancebo, J.; Net, A. Effect of PEEP on the arterial minus end-tidal carbon dioxide gradient. Chest 1987, 92, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doblar, D.D.; Santiago, T.V.; Kahn, A.U.; Edelman, N.H. The effect of positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation (PEEP) on cerebral blood flow and cerebrospinal fluid pressure in goats. Anesthesiology 1981, 55, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videtta, W.; Villarejo, F.; Cohen, M.; Domeniconi, G.; Santa Cruz, R.; Pinillos, O.; Rios, F.; Maskin, B. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure. In Intracranial Pressure and Brain Biochemical Monitoring; Acta Neurochirurgica Supplements; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2002; Volume 81, pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Ball, L.; Nogas, S.; Battaglini, D.; Messina, A.; Brunetti, I.; Minetti, G.; Castellan, L.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Pelosi, P. Effects of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure on Lung Recruitment, Respiratory Mechanics, and Intracranial Pressure in Mechanically Ventilated Brain-Injured Patients. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 711273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, D.; Schwarz, S.; Baumgartner, R.W.; Veltkamp, R.; Schwab, S. Influence of positive end-expiratory pressure on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure in patients with acute stroke. Stroke 2001, 32, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, M.D.; Jinadasa, S.P.; Mueller, A.; Shaefi, S.; Kasper, E.M.; Hanafy, K.A.; O’Gara, B.P.; Talmor, D.S. The Effect of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure on Intracranial Pressure and Cerebral Hemodynamics. Neurocrit. Care 2017, 26, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barea-Mendoza, J.A.; Molina-Collado, Z.; Ballesteros-Sanz, M.A.; Corral-Ansa, L.; Misis Del Campo, M.; Pardo-Rey, C.; Tihista-Jimenez, J.A.; Corcobado-Marquez, C.; Martin Del Rincon, J.P.; Llompart-Pou, J.A.; et al. Effects of PEEP on intracranial pressure in patients with acute brain injury: An observational, prospective and multicenter study. Med. Intensiva (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 48, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, G.; Crossley, D.; Richards, J.; Wong, D. Effects of varying levels of positive end-expiratory pressure on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 25, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, J. Positive end-expiratory pressure-induced increase in central venous pressure to predict fluid responsiveness: Don’t forget the peripheral venous circulation! Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.P.; Lin, Y.N.; Cheng, Z.H.; Qu, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.Y. Intracranial-to-central venous pressure gap predicts the responsiveness of intracranial pressure to PEEP in patients with traumatic brain injury: A prospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongstad, L.; Grande, P.O. The role of arterial and venous pressure for volume regulation of an organ enclosed in a rigid compartment with application to the injured brain. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1999, 43, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, L. Acute lung injury in patients with severe brain injury: A double hit model. Neurocrit Care 2009, 11, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Fluid management strategies in critically ill patients with ARDS: A narrative review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picetti, E.; Pelosi, P.; Taccone, F.S.; Citerio, G.; Mancebo, J.; Robba, C.; The ESICM NIC/ARF Sections. VENTILatOry strategies in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: The VENTILO Survey of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Crit. Care 2020, 24, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Camporota, L.; Citerio, G. Acute respiratory distress syndrome complicating traumatic brain injury. Can opposite strategies converge? Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. ARDS associated acute brain injury: From the lung to the brain. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharie, S.A.; Almari, R.; Azzam, S.; Al-Husinat, L.; Araydah, M.; Battaglini, D.; Schultz, M.J.; Patroniti, N.A.; Rocco, P.R.; Robba, C. Brain Protective Ventilation Strategies in Severe Acute Brain Injury. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 25, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A.W.; Lin, H.S.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Brown, J.B.; Moore, E.E.; Schreiber, M.A.; Joseph, B.; Wilson, C.T.; Cotton, B.A.; Ostermayer, D.G.; et al. Adverse Prehospital Events and Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2457506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, A.; Poynter, E.; Garner, A.; Lee, A. Near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring in a pre-hospital trauma patient cohort: An analysis of successful signal collection. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2020, 64, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, E.L.; Mercer, M.P.; Wood, A.J.; Amorim, E.; Kleen, J.K.; Gerard, D.; Kellison, C.; Yamashita, S.; Auerbach, B.; Joshi, N.; et al. Evaluating the feasibility of prehospital point-of-care EEG: The prehospital implementation of rapid EEG (PHIRE) study. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaither, J.B.; Spaite, D.W.; Bobrow, B.J.; Barnhart, B.; Chikani, V.; Denninghoff, K.R.; Bradley, G.H.; Rice, A.D.; Howard, J.T.; Keim, S.M.; et al. EMS Treatment Guidelines in Major Traumatic Brain Injury With Positive Pressure Ventilation. JAMA Surg. 2024, 159, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravesteijn, B.Y.; Sewalt, C.A.; Nieboer, D.; Menon, D.K.; Maas, A.; Lecky, F.; Klimek, M.; Lingsma, H.F.; CENTER-TBI Collaborators. Tracheal intubation in traumatic brain injury: A multicentre prospective observational study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Schoettker, P.; Henzi, I.; Osterwalder, J.; Walder, B. Pre-hospital tracheal intubation in patients with traumatic brain injury: Systematic review of current evidence. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009, 103, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brinker, V.; Exadaktylos, A.; Hautz, W.; Ziaka, M. First Breath Matters: Out-of-Hospital Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238443

Brinker V, Exadaktylos A, Hautz W, Ziaka M. First Breath Matters: Out-of-Hospital Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238443

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrinker, Victoria, Aristomenis Exadaktylos, Wolf Hautz, and Mairi Ziaka. 2025. "First Breath Matters: Out-of-Hospital Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238443

APA StyleBrinker, V., Exadaktylos, A., Hautz, W., & Ziaka, M. (2025). First Breath Matters: Out-of-Hospital Mechanical Ventilation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238443