Ovarian Collision Tumor in a Pediatric Patient: A Mature Teratoma Associated with a Combined Tumor Containing a Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma Component

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient Information

2.2. Clinical Findings

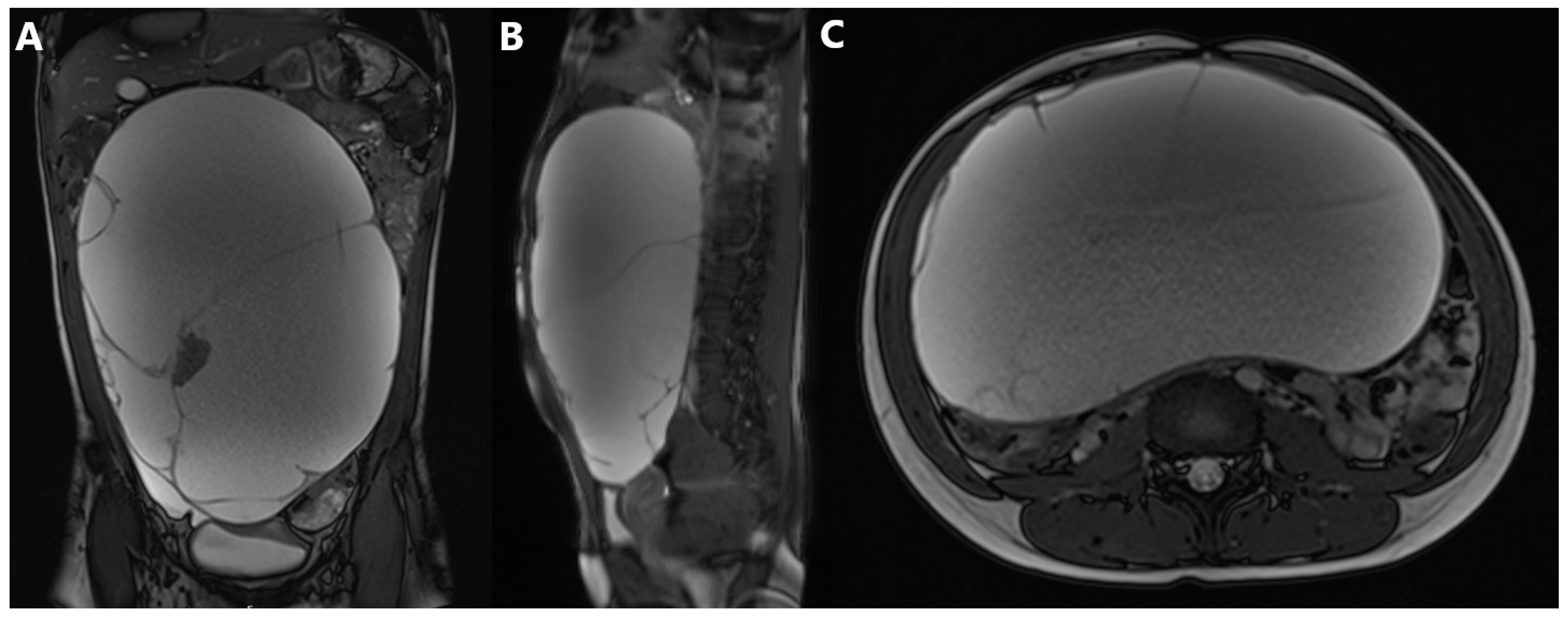

2.3. Diagnostic Assessment

2.4. Therapeutic Intervention

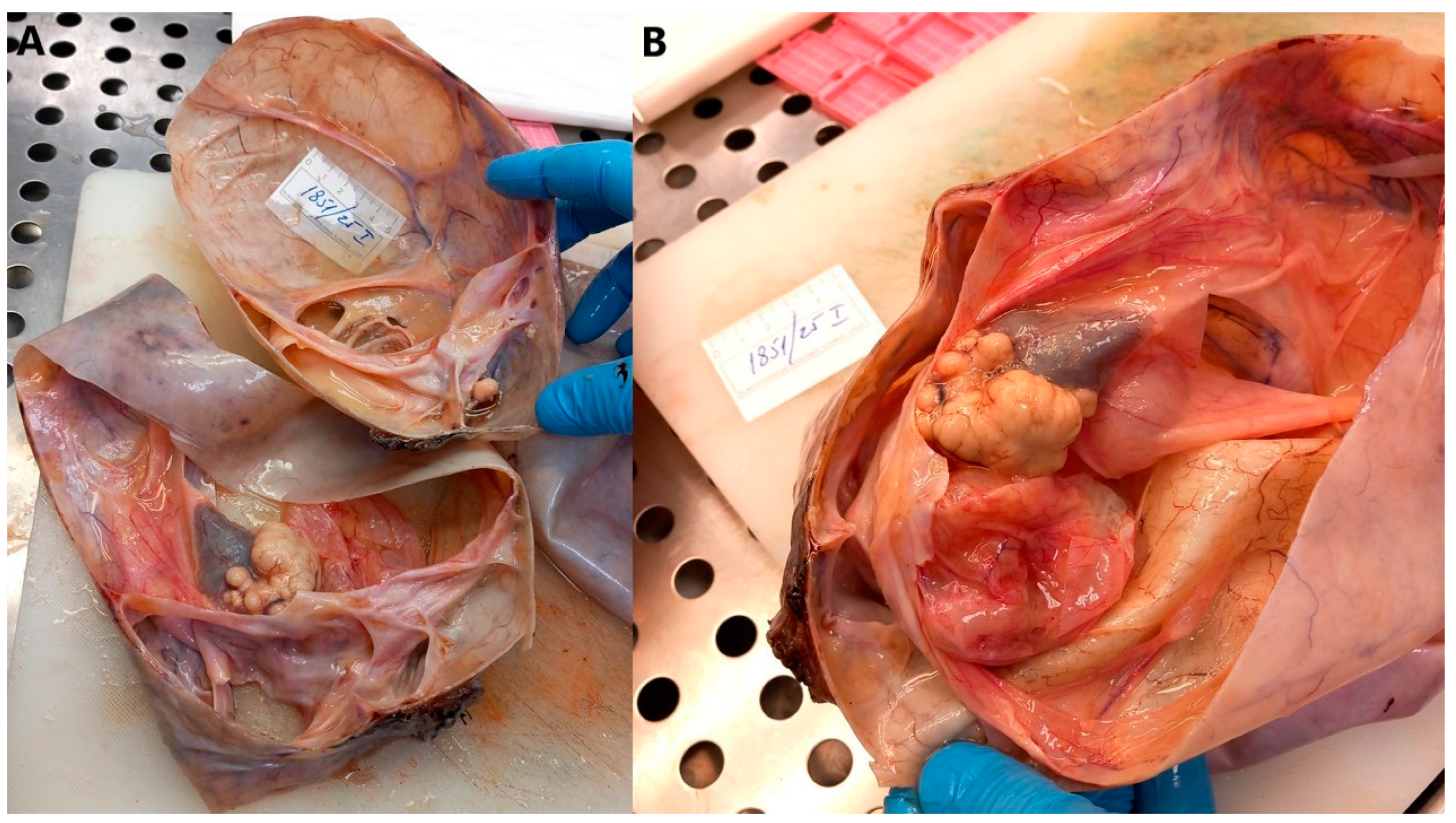

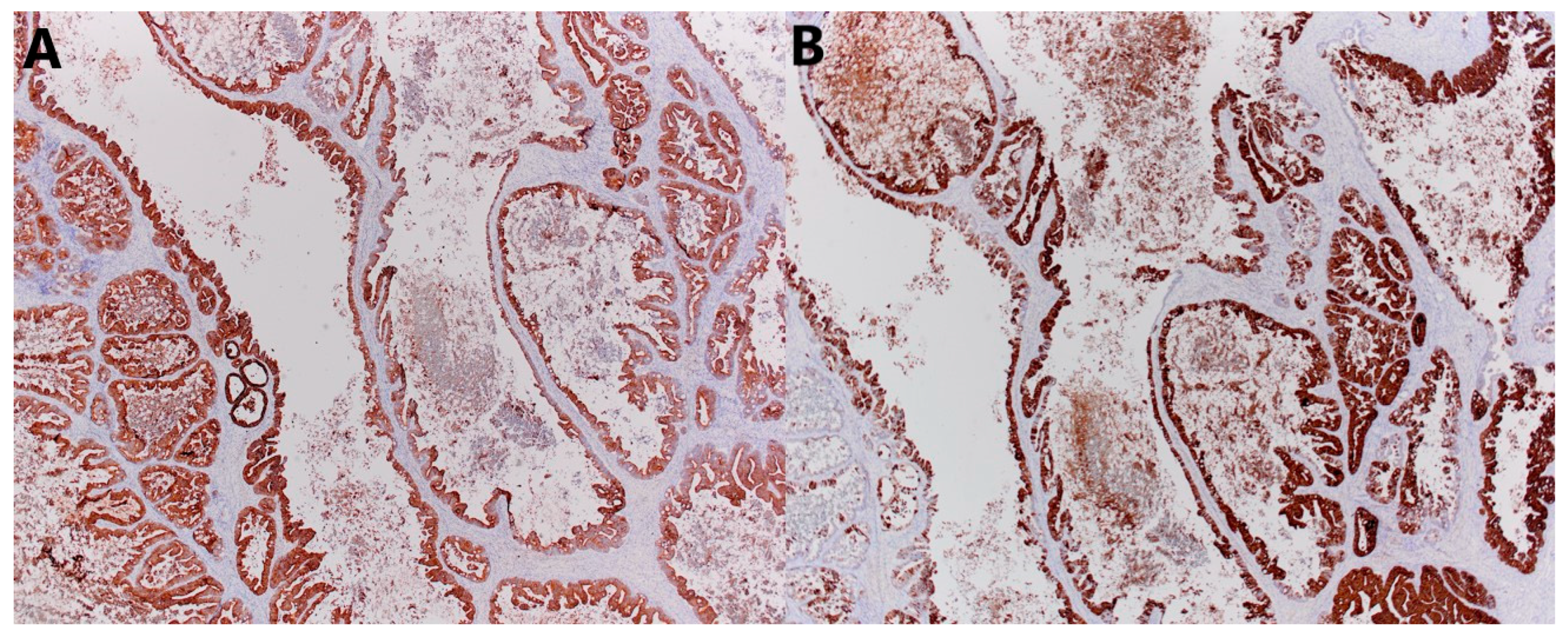

2.5. Histopathological Analysis

2.6. Follow-Up and Outcomes

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LL | Latero-lateral |

| AP | Antero-posterior |

| CC | Cranio-caudal |

| US | Ultrasound |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PET-CT | Positron emission tomography–computed tomography |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| FER | Ferritin |

| HCG | Human chorionic gonadotropin |

| NSE | Neuron-specific enolase |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CA | Cancer antigen |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

References

- Taskinen, S.; Fagerholm, R.; Lohi, J.; Taskinen, M. Pediatric ovarian neoplastic tumors: Incidence, age at presentation, tumor markers and outcome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birbas, E.; Kanavos, T.; Gkrozou, F.; Skentou, C.; Daniilidis, A.; Vatopoulou, A. Ovarian Masses in Children and Adolescents: A Review of the Literature with Emphasis on the Diagnostic Approach. Children 2023, 10, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussios, S.; Attygalle, A.; Hazell, S.; Moschetta, M.; McLachlan, J.; Okines, A.; Banerjee, S. Malignant Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors in Postmenopausal Patients: The Royal Marsden Experience and Literature Review. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 6713–6722. [Google Scholar]

- Jakimovska Stefanovska, M.; Čelebić, A.; Calleja-Agius, J.; Drusany Staric, K. Ovarian cancer in children and adolescents: A unique clinical challenge. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 108785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saani, I.; Raj, N.; Sood, R.; Ansari, S.; Mandviwala, H.A.; Sanchez, E.; Boussios, S. Clinical Challenges in the Management of Malignant Ovarian Germ Cell Tumours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023, 20, 6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkrozou, F.; Tsonis, O.; Vatopoulou, A.; Galaziou, G.; Paschopoulos, M. Ovarian Teratomas in Children and Adolescents: Our Own Experience and Review of Literature. Children 2022, 9, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadrack, M.; Ali, S.J.; Andrea, R.S.; Bokhary, Z.; Ngotta, V.; Ngiloi, P. Delayed presentation of mature teratoma with umbilical perforation in a 9-years old female without congenital abdominal wall defects: A rare case report of atypical teratoma location. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2025, 130, 111285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzillo, C.; Imparato, A.; Fortarezza, F.; Maniglio, S.; Lucà, S.; La Verde, M.; Serio, G.; Marzullo, A. Gonadal Teratomas: A State-of-the-Art Review in Pathology. Cancers 2024, 16, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Wang, S.; Yeung, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.S.; Chung, J.P.W.; Chan, D.Y.L. Mature Cystic Teratoma: An Integrated Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zou, C.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Yan, T. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary in a 14-year-old girl: A case report and literature review. BMC Womens Health. 2023, 23, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beroukhim, G.; Ozgediz, D.; Cohen, P.J.; Hui, P.; Morotti, R.; Schwartz, P.E.; Yang-Hartwich; Vash-Margita, A. Progression of Cystadenoma to Mucinous Borderline Ovarian Tumor in Young Females: Case Series and Literature Review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2022, 35, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkhchi, P.; Cybulski, C.; Gronwald, J.; Wong, F.O.; Narod, S.A.; Akbari, M.R. CA125 and Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2020, 12, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Fang, L. Salpingo-oophorectomy versus cystectomy in patients with borderline ovarian tumors: A systemic review and meta-analysis on postoperative recurrence and fertility. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaier, A.; Ghatage, P. Mucinous Cancer of the Ovary: Overview and Current Status. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Lin, J.; Guan, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.; Guo, Y. Ovarian collision tumors: Imaging findings, pathological characteristics, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 2156–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, M.; Silvestris, E.; Loizzi, V.; Cormio, G.; Cazzato, G.; Arezzo, F. A Rare Case of Collision Tumours of the Ovary: An Ovarian Serous Cystadenoma Coexisting with Fibrothecoma. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayed, A.M.; Almawi, A.S.; Alghamdi, E.G.; Alfaleh, H.S.; Kadasah, N.S. Ovarian Collision Tumor, Massive Mucinous Cystadenoma, and Benign Mature Cystic Teratoma. Cureus 2021, 13, e16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Kou, X.; Lan, Y.; Jia, Y. A collision tumor composed of colon adenocarcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with gingival metastasis: A case report. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1633770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumny, F.; Speisky, D.; Rizzolo, M.; Sánchez, M.F.; Garavaglia, G.; Kujaruk, M. Collision tumor of a primary colonic adenocarcinoma and a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Medicina 2025, 85, 610–614. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Chin, S.; Lim, C.W.; Kim, Z.; Hur, S.M. Collision tumor of thyroid: A case report of synchronous papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Medicine 2025, 104, e43982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulte, C.A.; Hoegler, K.M.; Khachemoune, A. Collision tumors: A review of their types, pathogenesis, and diagnostic challenges. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorella, I.; Memeo, L.; Ciardi, A.; Rotterdam, H. An unusual case of colonic mixed adenoendocrine carcinoma: Collision versus composite tumor. A case report and review of the literature. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2007, 11, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, G.; Blandino, A.; Pergolizzi, S.; Ascenti, G.; Mazziotti, S. Collision and composition tumors: Rare conditions to remember in differential diagnosis of adrenal glands lesions. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 1902–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, J.K.; Soslow, R.A.; Longacre, T.A. Ovarian mature teratomas with mucinous epithelial neoplasms: Morphologic heterogeneity and association with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, B.K.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, B.H.; Byun, J.Y. Collision tumors of the ovary associated with teratoma: Clues to the correct preoperative diagnosis. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1999, 23, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bige, O.; Demir, A.; Koyuncuoglu, M.; Secil, M.; Ulukus, C.; Saygili, U. Collision tumor: Serous cystadenocarcinoma and dermoid cyst in the same ovary. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 279, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, M. Collision tumours of ovary: A very rare case series. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, FD14–FD16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Dey, M.K.; Devireddy, R.; Gartia, M.R. Biomarkers in Cancer Detection, Diagnosis, and Prognosis. Sensors 2023, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.C.; Irshaid, L.; Mathur, M. Multimodality Imaging Approach to Ovarian Neoplasms with Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2021, 41, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatta, G.; Calleja-Agius, J.; Sandrucci, S.; Bennet, D.; Azzopardi, M.J.; Capocaccia, R.; EUROCARE WG. Incidence and survival of rare female genital tract cancers in Europe: The EUROCARE-6 study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 109996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canlorbe, G.; Chabbert-Buffet, N.; Uzan, C. Fertility-Sparing Surgery for Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, R.; Gown, A.M.; Zhao, C.; Barry, T.S.; Isacson, C.; Richardson, M.S.; Ronnett, B.M. Ovarian mucinous tumors associated with mature cystic teratomas: Morphologic and immunohistochemical analysis identifies a subset of potential teratomatous origin that shares features of lower gastrointestinal tract mucinous tumors more commonly encountered as secondary tumors in the ovary. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dundr, P.; Singh, N.; Nožičková, B.; Němejcová, K.; Bártů, M.; Stružinská, I. Primary mucinous ovarian tumors vs. ovarian metastases from gastrointestinal tract, pancreas and biliary tree: A review of current problematics. Diagn. Pathol. 2021, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, O.; Hamadeh, A.; Pourvaziri, A.; Mercaldo, S.; Clark, J.; McLay, K.; Harisinghani, M. Differentiating primary from metastatic ovarian tumors of gastrointestinal origin by CT. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2025, 54, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.K.; Ding, D.C. Early Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of the Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberto, J.M.; Chen, S.Y.; Shih, I.M.; Wang, T.H.; Wang, T.L.; Pisanic, T.R., 2nd. Current and Emerging Methods for Ovarian Cancer Screening and Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keretić, D.; Petračić, I.; Mašić Binder, S.; Ulamec, M.; Plavec Živko, A.; Stepan Giljević, J.; Bonevski, A.; Habek, D.; Bašković, M. Ovarian Collision Tumor in a Pediatric Patient: A Mature Teratoma Associated with a Combined Tumor Containing a Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma Component. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186387

Keretić D, Petračić I, Mašić Binder S, Ulamec M, Plavec Živko A, Stepan Giljević J, Bonevski A, Habek D, Bašković M. Ovarian Collision Tumor in a Pediatric Patient: A Mature Teratoma Associated with a Combined Tumor Containing a Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma Component. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186387

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeretić, Dorotea, Ivan Petračić, Silvija Mašić Binder, Monika Ulamec, Andrea Plavec Živko, Jasminka Stepan Giljević, Aleksandra Bonevski, Dubravko Habek, and Marko Bašković. 2025. "Ovarian Collision Tumor in a Pediatric Patient: A Mature Teratoma Associated with a Combined Tumor Containing a Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma Component" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186387

APA StyleKeretić, D., Petračić, I., Mašić Binder, S., Ulamec, M., Plavec Živko, A., Stepan Giljević, J., Bonevski, A., Habek, D., & Bašković, M. (2025). Ovarian Collision Tumor in a Pediatric Patient: A Mature Teratoma Associated with a Combined Tumor Containing a Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma Component. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186387