Numerical Stability and Handling Studies of Three-Wheeled Vehicles Using ADAMS/Car

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Stability and Controllability of the Three-Wheeled Vehicles

1.2. Equations of Motion of the Vehicle in Terms of Wheels Configuration

2. Materials and Methods

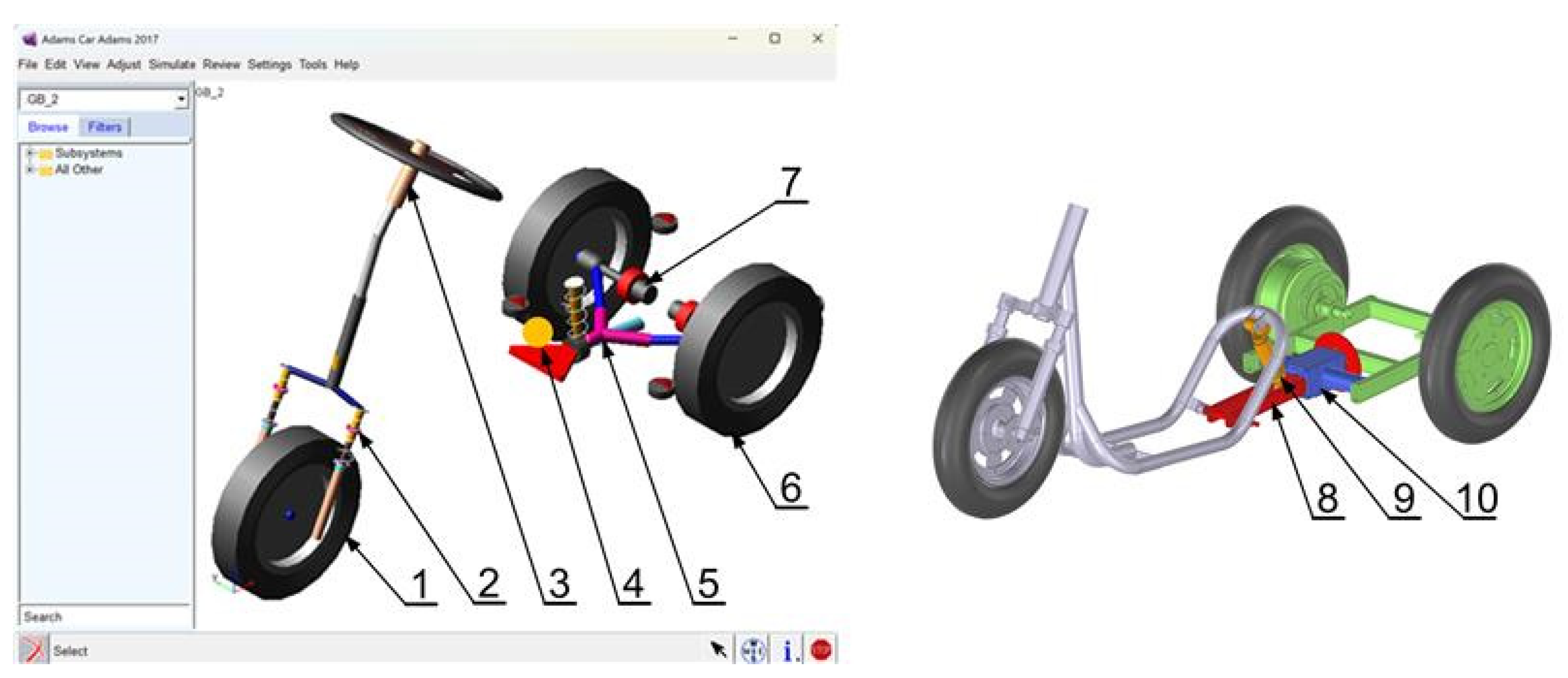

2.1. MSC.ADAMS/Car Model of the Tilted Three-Whelled Vehicle

2.2. Ramp Steer Simulation

2.3. Single-Lane Change Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ramp Steer Simulation Results

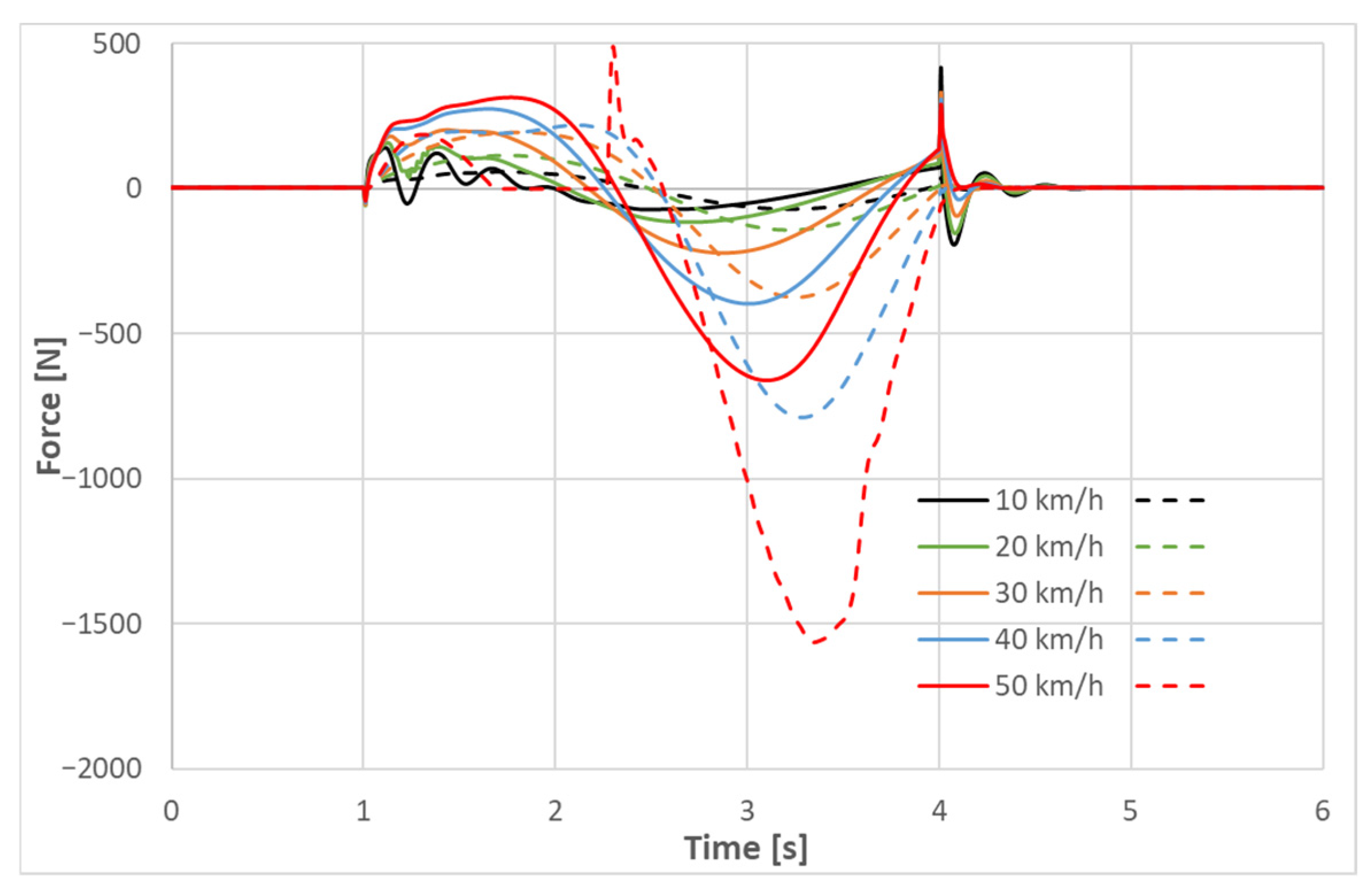

3.2. Single-Lane Change Simulation Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caban, J. Traffic congestion level in 10 selected cities of Poland. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2021, 112, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caban, J.; Droździel, P. Traffic congestion in chosen cities of Poland. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2020, 108, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caban, J.; Voltr, O. A Study on the use of eco-driving technique in city traffic. Arch. Automot. Eng. Arch. Motoryz. 2021, 93, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, A.; Caban, J. Organization of Urban Transport Organization—Presentation of Bicycle System and Bicycle Infrastructure in Lublin. LOGI—Sci. J. Transp. Logist. 2021, 12, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhao, H. A Review of Research on Coordinated Control of Traffic Signals at Urban Road Intersection Groups. Promet—Traffic Transp. 2025, 37, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palo, J.; Stopka, O. On-site traffic management evaluation and proposals to improve safety of access to workplaces. Commun.—Sci. Lett. Univ. Žilina 2021, 23, A125–A136. [Google Scholar]

- Stopka, O.; Sarkan, B.; Chovancova, M.; Kapustina, L.M. Determination of the appropriate vehicle operating in particular urban traffic conditions. Commun.—Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2017, 19, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dižo, J.; Blatnický, M.; Lovska, A.; Molnár, D.; Šuvada, R. An Engineering Design of a Scooter. In Machine and Industrial Design in Mechanical Engineering; Rackov, M., Miltenović, A., Banić, M., Eds.; KOD 2024. Mechanisms and Machine Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szemere, D.; Nemeslaki, A. The implications of electric scooters as a new technology artifact in urban transportation. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2023, 20, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K.; Kubik, A.; Folęga, P.; Chen, F. Perception of shared electric scooters: A case study from Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Q.; Xie, K.; Yang, D. Safety of micro-mobility: Analysis of E-Scooter crashes by mining news reports. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 143, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudziak, A.; Caban, J. The Urban Transport Strategy on the Example of the City Bike System in the City of Lublin in Relation to the COVID-19 Pandemic. LOGI—Sci. J. Transp. Logist. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalák, S.; Gogola, M.; Cerný, M. Options for assessing the impact of the bike-sharing system on mobility in the city Žilina. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 55, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathouský, B.; Mervart, M. The cycling transport in Prague. Perner’s Contacts 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatnický, M.; Dižo, J.; Sága, M.; Molnár, D.; Slíva, A. Utilizing Dynamic Analysis in the Complex Design of an Unconventional Three-Wheeled Vehicle with Enhancing Cornering Safety. Machines 2023, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Jaiswal, R.; Srivastava, A.; Verma, M. Design and Fabrication of an Electric Tricycle. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology, ICICAT 2023, Gorakhpur, India, 23–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jilek, P.; Berg, J.; Tchuigwa, B.S.S. Influence of the Weld Joint Position on the Mechanical Stress Concentration in the Construction of the Alternative Skid Car System’s Skid Chassis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilek, P.; Cerman, J. Design of sliding frame system for two-wheeled vehicle. In Transport Means—Proceedings of the International Conference; 2020; pp. 136–141. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10195/77047 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Yildiz, B.; Çiğdem, Ş.; Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, I. Sustainable mobility and electric vehicle adoption: A study on the impact of perceived benefits and risks. Transport 2024, 39, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatnický, M.; Dižo, J.; Molnár, D.; Suchánek, A. Comprehensive Analysis of a Tricycle Structure with a Steering System for Improvement of Driving Properties While Cornering. Materials 2022, 15, 8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dižo, J.; Blatnický, M.; Melnik, R.; Karľa, M. Improvement of Steerability and Driving Safety of an Electric Three-Wheeled Vehicle by a Design Modification of its Steering Mechanism. Logi Sci. J. Transp. Logist. 2022, 13, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukac, M.; Brumercik, F.; Krzywonos, L. Driveability simulation of vehicle with variant tire properties. Commun.—Sci. Lett. Univ. Žilina 2016, 18, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motrike. Delta vs. Tadpole Trike. Available online: https://www.motrike.com/delta-vs-tadpole-trike/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Honda Gyro Canopy. Available online: https://pl.e-scooter.co/honda-gyro-canopy/ (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Piaggio MP3 400 na 2021—Duży Skuter na Samochodowe Prawo Jazdy [Piaggio MP3 400 for 2021—Large Scooter for Car License Holders]. Available online: https://motogen.pl/piaggio-mp3-400-na-2021-duzy-skuter-na-samochodowe-prawo-jazdy-test/ (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Kukla, M.; Wieczorek, B.; Warguła, Ł.; Berdychowski, M. An analytical model of the demand for propulsion torque during manual wheelchair propelling. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 16, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B.; Kukla, M.; Warguła, Ł. The symmetric nature of the position distribution of the human body center of gravity during propelling manual wheelchairs with innovative propulsion systems. Symmetry 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańko-Pająk, K.; BBursa Seńko, J.; Detka, T.; Korczak, S.; Nowak, R.; Popiołek, K.; Lisiecki, J.; Paczkowski, A. Selected Aspects of Materials Engineering for Vehicle Design. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1247, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilek, P. Vehicle wheel positioning innovation on a machine for measuring the contact parameters between a tyre and the road. Arch. Automot. Eng. 2023, 100, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrucany, T.; Vrabel, J.; Kazimir, P. The influence of the cargo weight and its position on the braking characteristics of light commercial vehicles. Open Eng. 2020, 10, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabel, J.; Jagelcak, J.; Stopka, O.; Kiktova, M.; Caban, J. Determination of the maximum permissible cargo length exceeding the articulated vehicle length in order to detect its critical rotation radius. In Proceedings of the XI International Science-Technical Conference Automotive Safety, Casta-Papiernicka, Slovakia, 18–20 April 2018; pp. 1–7, ISBN 978-1-5386-4579-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Shao, Z. Stability Analysis of a Vehicle–Cargo Securing System for Autonomous Trucks Based on 6-SPS-Type Parallel Mechanisms. Machines 2023, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, M.P.; Chonhenchob, V.; Singh, S.P.; Sittipod, S. Measurement and Analysis of Vibration Levels in Two and Three Wheel Delivery Vehicles in Southeast Asia. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniążek, W.; Więckowski, D. Badania Kierowalności i Stateczności Pojazdów Samochodowych; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frej, D.; Hupka, M. The vehicle insurance and the risk of road accidents in Poland. Arch. Automot. Eng. 2025, 107, 49–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybicka, I.; Caban, J.; Vrabel, J.; Šarkan, B.; Stopka, O.; Misztal, W. Analysis of the safety systems damage on the example of a suburban transport enterprise. In Proceedings of the XI International Science-Technical Conference Automotive Safety, Casta-Papiernicka, Slovakia, 18–20 April 2018; pp. 1–6, ISBN 978-1-5386-4579-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorum, N.G.; Sorum, M.G. Prediction and Investigation of the Injury Severity of Drivers Involved in Speeding-Related Crashes Using Machine Learning Models. Promet—Traffic Transp. 2025, 37, 1612–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Increasing the Road Safety of E-bike: Design of Protective Shells Based on Stability Criterion. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, Ž.; Tretjakovas, J.; Drozd, K.; Rudzinskas, V.; Walczak, M.; Kilikevičius, A.; Matijosius, J.; Boretska, I. Material’s Strength Analysis of the Coupling Node of Axle of the Truck Trailer. Materials 2023, 16, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosobudzki, M.; Zajac, P.; Gardyński, L. A Model-Based Approach for Setting the Initial Angle of the Drive Axles in a 4 × 4 High Mobility Wheeled Vehicle. Energies 2023, 16, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravilonis, T.; Sokolovskij, E. Analysis of composite material properties and their possibilities to use them in bus frame construction. Transport 2020, 35, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilek, P.; Nemec, J. Changing adhesion force for testing road vehicles at safe speed. Eng. Rural. Dev. 2020, 19, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, J.C.; Graves, B.J.; Johnson, D.B. Three Wheeled Vehicle Dynamics; SAE Technical Paper 820139; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagelčák, J.; Gnap, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Kuba, O.; Frnda, J. Calculation of an Average Vehicle’s Sideways Acceleration on Small Roundabouts. Sensors 2022, 22, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagelčák, J.; Kiktová, M.; Frančák, M. The Analysis of Manoeuvrability of Semi-trailer Vehicle Combination. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 44, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabel, J.; Skrucany, T.; Bartuska, L.; Koprna, J. Movement analysis of the semitrailer with the tank-container at hard braking-the case study. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 710, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, K.; Sano, K.; Watanabe, K.; Kaieda, T.; Takano, K. Study on the Behavior of Three-Wheeled Vehicles Travelling over Low-μ Road Surfaces; Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd.: Iwata, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Lee, T. Analysis of Stability of Three- and Four-Wheeled Vehicles. Seria III 1990, 33, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R. Ride, eigenvalue and stability analysis of three-wheel vehicle using Lagrangian dynamics; Maharishi Markandeshwar University: Mullana, India, 2017; No. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, D. Stability of Three-Wheeled Vehicles and Bicycles; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Worcester Polytechnic Institute: Worcester, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saeedi, A.; Kazemi, R. Stability of Three-Wheeled Vehicles with and without Control System. Int. J. Automot. Eng. 2012, 2, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nieoczym, A.; Drozd, K. Fractographic Assessment and FEM Energy Analysis of the Penetrability of a 6061-T Aluminum Ballistic Panel by a Fragment Simulating Projectile. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2021, 15, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkevich, O.; Nikonova, T.; Gierz, Ł.; Berg, A.; Berg, A.; Zhunuspekov, D.; Warguła, Ł.; Łykowski, W.; Fryczyński, K. Parametric Optimization of a New Gear Pump Casing Based on Weight Using a Finite Element Method. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosłaniec, K. Analysis of the effect of projectile impact angle on the puncture of a steel plate using the finite element method in Abaqus software. Appl. Comput. Sci. 2022, 18, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulička, J.; Jílek, P. The Fourier analysis in transport application using Matlab. In Proceedings of the Transport Means International Conference, Juodkrantė, Lithuania, 5–7 October 2016; pp. 820–825. [Google Scholar]

- Seńko, J.; Nowak, R. Symulacyjne badania pojazdu typu Formula Student. Logistyka 2010, 2, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, T.; Seńko, J.; Jasiński, P.; Paczkowski, A. Selected Issues Related to the Research on Hybrid Three-Wheeler for Disabled. Arch. Motoryz. 2018, 80, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navikas, M.; Pitrėnas, P. Determination and Evaluation of a Three-Wheeled Tilting Vehicle Prototype’s Dynamic Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel-Milleret, A. Steady-state comparison of torque vectoring and vehicle tilt influence on narrow vehicle steering characteristics, Oeconomia. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, H. Obstacle avoidance capabilities of PMVs with inward active tilt. Sensors 2025, 8, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Khadr, A. Multibody dynamics modeling and simulation of a three-wheeled mobile robot using a robotic approach, Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory. Int. J. Intell. Unmanned Syst. 2024, 12, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Gu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y. Research on steering-tilting characteristics of an active tilting three-wheeled vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2023, 37, 2831–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Hang, W.; Chen, H. A novel in-situ sensor calibration method for building thermal systems based on virtual samples and autoencoder. Energy 2024, 297, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Shi, L.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Yang, P.; Xiao, H.; Chen, D.; Zhao, P. Virtual sample diffusion generation method guided by large language model-generated knowledge for enhancing information completeness and zero-shot fault diagnosis in building thermal systems. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2025, 26, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle’s length | L | 1947 | mm |

| Vehicle’s height | H | 1777 | mm |

| Vehicle’s width | W | 801 | mm |

| Mass | m | 353 | kg |

| Center of gravity height z | xc | 307 | mm |

| Center of gravity height x | zc | 1028 | mm |

| Wheelbase | Wb | 1520 | mm |

| Track width | Tb | 700 | mm |

| Front and rear tires | - | 90/90–12 | - |

| Rake | Ra | 67.5 | degree |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stańko-Pająk, K.; Seńko, J.; Nowak, R.; Rymuszka, M.; Danielewicz, D.; Jóźwik, K. Numerical Stability and Handling Studies of Three-Wheeled Vehicles Using ADAMS/Car. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010098

Stańko-Pająk K, Seńko J, Nowak R, Rymuszka M, Danielewicz D, Jóźwik K. Numerical Stability and Handling Studies of Three-Wheeled Vehicles Using ADAMS/Car. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleStańko-Pająk, Katarzyna, Jarosław Seńko, Radosław Nowak, Maciej Rymuszka, Dariusz Danielewicz, and Kamil Jóźwik. 2026. "Numerical Stability and Handling Studies of Three-Wheeled Vehicles Using ADAMS/Car" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010098

APA StyleStańko-Pająk, K., Seńko, J., Nowak, R., Rymuszka, M., Danielewicz, D., & Jóźwik, K. (2026). Numerical Stability and Handling Studies of Three-Wheeled Vehicles Using ADAMS/Car. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010098