1. Introduction

Selecting an exploitation method is a key decision that should be made at the very start of a project [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The selection of the method—surface, underground, or combined—depends on factors such as deposit size, shape, and orientation; rock mass properties; mining capacity and losses; recovery rate; overburden volume; machinery capabilities; environmental and social aspects; climate; discount rate; investment costs; mining costs; depreciation; and profit [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The primary objective is to find the most favourable mine contour at which exploitation is economically optimal (profitable), while also ensuring that safety and environmental protection requirements are met.

Underground mining offers several advantages over surface mining, including land reclamation, better control of deposit quality, economic value, operational flexibility, improved safety, and lower environmental impact—which is now a key factor [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Accurately determining the optimal exploitation contour for surface, underground, or combined mining is essential for minimising financial investment during mine development [

14,

15,

16].

In the literature, the term optimal depth and final contour of an open pit is stated as the contour within which exploitation is technologically, environmentally, and economically acceptable (profitable); however, this does not apply to dimension stone (DS) deposits [

17,

18]. Most DS quarries do not recognise the concept of optimal depth, as exploitation is primarily conducted above the basic ground level. Furthermore, optimal depth refers to the one–dimensional field of open pits that develop from the surface towards the deeper parts of the deposit, while the final contour denotes the temporal dimension, usually representing the final state of deposit exploitation. Determining the optimal exploitation contour or optimal transition point (OTP) from surface to underground exploitation is important and should be established during the initial planning phases.

Bastante et al. [

19] apply optimisation algorithms—traditionally used for non-stratified deposits such as metal ores—to enhance the exploitation of DS deposits by designing, planning, and scheduling exploitation phases. A deposit model was created that included a block and a financial model of the deposit. The block model of the deposit was represented by the number of recoverable blocks, i.e., stone slabs, while the financial model introduced the relationship between the stripping ratio and the stone slabs.

Using a heuristic algorithm based on an economic block model, Bakhtavar and Shahriar [

13] compared the values of blocks for both surface and underground mining methods at each horizon. By identifying the first positive-value blocks for underground mining at a given horizon, they determined the transition point, that is, the depth at which surface mining ends and underground mining begins.

Bakhtavar et al. [

20] determined the optimal contour for transitioning from surface to underground exploration using a derived economic-mathematical formula. The method is based on the economically justified overall stripping ratio and the permissible stripping ratio. This methodology is applicable to ore deposits that extend from the surface to the depth.

Opoku and Musingwini [

21] consider the current method for determining the optimal transition point from surface to underground exploitation to be insufficiently accurate as it is based on static models that do not account for changes throughout the lifespan of the gold mine. The authors argue that the issue should be approached stochastically, developing several exploitation models (surface, underground, and combined methods) for the same deposit. They emphasize the need to consider the sale price and quality of the mineral resource, geological unpredictability of the ore body, market fluctuations, and many other factors. The authors introduce the concept of a temporally variable “transition point” from surface to underground exploitation of gold deposits.

De Carli et al. [

22] analyse the optimal transition point from surface to underground mining, using a gold deposit as a case study. They compared several different scenarios involving combined mining methods, as well as evaluating each method separately, with the aim of maximising the project’s net present value and the quantity of exploited mineral resources. The authors emphasize that determining the optimal transition point is crucial for the continuation of exploitation since an incorrectly defined transition point from surface to underground mining can result in unprofitable underground mining due to an insufficient quantity of mineral resources for exploitation, ultimately leading to project termination.

Bakhtavar et al. [

23] introduce a stochastic mathematical model that uses a long-term surface mining plan on an integrated block model of surface and underground exploitation to determine the optimal transition point, i.e., the transition from surface to underground mining. In the block model, ore quality is treated as a random parameter of the main function, and changes in ore quality are constrained, with the main function seeking to maximize the net present value when combining surface and underground mining methods.

When determining the optimal depth for transitioning from surface to underground mining, the use of economic block models and Monte Carlo price simulations is introduced. For instance, in the case of a copper mine, an optimal transition depth of 375 m was established [

24]. Badakhshan et al. [

25] and Bakhtavar et al. [

26] explore similar models in their studies, and depending on geological, economic, and environmental parameters, a wide range of optimal transition depths has been identified, from 62.5 m to as much as 950 m.

To maximize the economic value of the project and its prospective mining operations, it is essential to integrate both surface and underground mining methods from the beginning of the project, rather than planning these approaches independently [

27,

28].

By applying a stochastic approach to optimisation, models that account for uncertainty in geological data and market prices have demonstrated an increase in net present value (NPV) of up to 9% compared with deterministic approaches [

29], while in the case of the gold mine, MacNeil et al. [

30] achieved an NPV increase of as much as 23%.

When analysing and selecting the optimal transition point from surface to underground mining, it is necessary to consider various aspects such as safety, technical, and other factors to more reliably determine the point of transition from one mining method to another. Dintwe et al. [

31], in their work, introduce the use of numerical models that examine potential occurrences of slope instability, ground subsidence, and collapse of underground chambers. Zhang et al. [

32] stated that the safety aspects of this type of mining differ from conventional ones and require specialized protocols and training. According to Soltani Khaboushan et al. [

33], equally important criteria, which are increasingly being incorporated into decision-making systems and the selection of optimal solutions for a given project, are environmental and social criteria. From an environmental perspective, underground mining results in a reduced environmental impact, such as lower amounts of waste rock and preservation of the surface cover. Badakhshan et al. [

34], using the example of the Sungun copper mine, showed that a transition depth ranging from 887.5 to 950 m, even when including environmental costs, resulted in a net present value (NPV) higher than USD 7.5 billion, with 67.7% of the overall impact being economic in nature, whilst environmental and social factors accounted for 41.7% and 39.8% of the total sustainability assessment, respectively.

Afum and Ben-Awuah [

35] present in their work a comprehensive review and analysis of the literature by various authors who, over the past decade, have addressed the topic of transitioning from surface to underground deposit exploitation. The authors state that understanding existing tools and methodologies is crucial for planning the transition from one method of exploitation to another.

Despite the availability of advanced tools and models, the timely and comprehensive planning of transitional phases is still not undertaken during the preparation of mining projects, which leads to suboptimal results and potential long-term consequences [

36,

37].

Extensive scientific research into the transition from surface to underground mining has been conducted on stratified, massive, and irregular metal deposits. However, the scientific literature does not record any research into the optimal transition point from surface to underground exploitation in dimension stone deposits. In this paper, a novel method for determining the optimal transition point from surface to underground exploitation of dimension stone deposits is presented, based on the analysis of techno-economic factors. The optimal transition point represents the economically optimal contour for surface, underground, or combined exploitation of the dimension stone deposit.

The dimension stone exploitation optimisation method (DS-EOM) represents a significant advancement in the modelling and evaluation of the transition from surface to underground mining for dimension stone deposits. In contrast to traditional methods designed for metal and coal deposits, which often utilize static block models, robust grade estimation, and regular deposit geometry assumptions, DS-EOM addresses the complexity and distinctive features of dimension stone deposits. These deposits are defined by heterogeneous recovery rates—where the economic value is tied to the proportion of marketable blocks rather than mineral grade—along with shallow and highly irregular geometries that make traditional block modelling inefficient and less representative. Additionally, dimension stone deposits are evaluated based on block quality and recoverable volume, not grade, necessitating a departure from grade-centric frameworks.

The DS-EOM method models the deposit as a sequence of exploitable layers instead of a detailed block-by-block approach. This layer-based representation is more flexible and better reflects the actual geological and operational conditions found in dimension stone deposits. Within this framework, blocks (block A, block B, and block C) are designated for either surface or underground exploitation, and techno-economic factors are calculated for each scenario to determine the optimal transition point.

A key innovation of the DS-EOM approach lies in its economic modelling process. Unlike earlier methods that require specialized software for techno–economic calculations, DS-EOM utilizes widely available spreadsheet tools, making the process more accessible and facilitating rapid adjustments in response to market changes. Stakeholders can dynamically evaluate profitability, recovery coefficients (which represent the ratio between the volume of commercial blocks and the total volume of exploited mass

and depend on the geological conditions within the deposit [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]), and cost structures, leading to real-time updates and greater adaptability in project planning. This capability stands in stark contrast to the rigidity of classical, software-dependent approaches, offering clear improvements in terms of flexibility and responsiveness.

Furthermore, DS-EOM prioritizes the direct calculation of economic impacts resulting from variable recovery rates and fluctuating costs. This enables a tailored determination of the optimal transition contour between surface and underground mining that accommodates the changing nature of both market and operational conditions. As a result, the method delivers a more precise, practical, and adaptable solution for identifying the best transition point, addressing the shortcomings of previous methodologies.

By integrating these conceptual and technical innovations, DS-EOM supports improved project planning and operational decision-making in dimension stone exploitation. The method not only enhances the accuracy of transition modelling but also empowers decision-makers with a tool that reflects the true complexity of dimension stone deposits, ultimately driving better economic outcomes and more sustainable exploitation strategies.

Table 1 presents the principal parameters of DS-EOM in comparison with the classical transition methods.

2. Materials and Methods

The DS-EOM, that is, the determination of the optimal exploitation contour, i.e., the optimal transition point (OTP) from surface to underground exploitation, consists of three main components:

The first section concerns the identification of the area or section of the deposit to be analysed, as well as the characteristics related to the selected area. This section covers all available data for the chosen location. Based on the collected data, three-dimensional models of the deposit and the terrain surface are created.

The second section concerns the three-dimensional models of the surface and the underground quarry, namely, the final contours of the quarry obtained through the exploitation of optimisation blocks, as well as the quantities of dimension stone (DS) and waste rock. The final contours of the quarry are determined based on design parameters, while the quarry volumes are calculated by measuring the volume of individual three-dimensional model parts.

The third section involves determining the economic values of the quarry models, that is, defining and analysing the costs (—costs of underground DS exploitation, EUR; —costs of surface DS exploitation, EUR), revenues, profits, and minimum selling prices of dimension stone blocks obtained through surface and underground exploitation. The position of the optimal exploitation contour, or the OTP from surface to underground exploitation, is established based on a comparative analysis of the economic values of the quarry models. In other words, it is determined which mining method should be used in which part of the deposit to maximise profit.

To determine the OTP from surface to underground exploitation, an algorithm has been developed to select between surface, underground, or combined methods of dimension stone deposit exploitation (see

Figure 1).

2.1. First Section

To determine the research area and apply the DS-EOM, it is necessary to consider all available data regarding a specific location, provided that the site is suitable for DS exploitation. By analysing all accessible information about the area, a deposit section is selected for which the greatest amount of data collected during exploration is available (such as geodetic data on the terrain surface, exploratory drilling, geological data, structural elements, details about the rock mass of the area, etc.) or a section for which minimal additional exploration of the site and deposit is required (e.g., exploratory drilling and similar activities) so that it can be chosen as the location where the DS-EOM will be applied.

Based on the available geodetic and geological data for the research area, a digital elevation model (DEM) of the terrain surface and a three-dimensional geological model of the deposit were created.

Within the defined research area, a section with the most available exploration data has been selected, and the DS-EOM will be implemented within the boundaries of this identified section of the research model. The optimisation method will be carried out in segments, meaning specific parts of the deposit—blocks within the selected boundaries—will be designated for either surface or underground exploitation. In this study, three blocks (A, B, and C) have been identified for analysis.

2.2. Second Section

For each block (A, B, and C) in the optimisation model, the final contours of both the surface and underground quarries have been designed. The condition was set that each block (A, B and C) in the optimisation model must be fully exploited, regardless of the chosen mining method or the quarry’s final contour. Additionally, it was specified that due to the specifics of each exploitation method, all activities required to commence the exploitation of block A would be considered preparatory works and would not be considered during the economic analysis of the exploitation methods. The final contours of the surface and underground quarries for blocks A, B, and C continue from the preparatory stage, which is the same across all models.

For each block in the exploitation optimisation model, new surface and underground quarries are designed, along with their final contours, to ensure the entire block is fully exploited. Both surface and underground quarries are modelled based on the established values of the design parameters.

The design process is undertaken in a three-dimensional environment. This approach immediately generates models of the final quarry contours, enabling calculation of exploited volumes of DS and waste rock for both surface and underground quarries.

When calculating the quantities of DS, all rock mass losses can be expressed through the recovery coefficient of the DS deposit .

2.3. Third Section

The definition of the economic values of quarries (both surface and underground) is necessary to determine the profitability of exploitation, that is, the limit contour at which exploitation becomes economically justified.

Put simply, underground exploitation of DS is more cost-effective than surface exploitation, according to Expression (1), if mining occurs only in DS layers:

where

—costs of underground DS exploitation (EUR),

—costs of surface DS exploitation (EUR),

—costs of surface overburden removal (EUR),

—costs of land reclamation (EUR).

To determine the profitability of exploitation, that is, the limit contour at which exploitation becomes economically justified, it is necessary to establish the economic or market values that can be achieved through the sale of mineral raw materials, as well as the total DS exploitation costs. This is primarily carried out at the very beginning, that is, prior to the commencement of mining activities, through preliminary, pre-investment, and investment studies [

43]. To enable a comparison of the economic values of block exploitation by either surface or underground mining, identical parameters have been established for all blocks and all methods of exploitation. The analysis covers the following factors: the volume of DS blocks and the economic values of costs, revenues, and profits from exploitation, as well as the unit cost of exploiting DS stone blocks.

The net value of the quarry can be determined using the following expression:

where

—the value of the deposit expressed as the net profit from the sale of DS blocks (EUR),

—market value of commercial DS blocks (EUR/m3),

—average exploitation costs of commercial DS blocks (EUR/m3),

—total quantity of commercial DS blocks (m3).

Based on the economic values of surface and underground quarries, an analysis of the results of the final quarries contours is conducted [

43].

The quantity of commercial blocks is calculated separately for each productive layer, given that different productive layers have different recovery rates. This is done by multiplying the quantity of exploited rock mass from each productive layer by the recovery coefficient for that layer. The quantity of commercial blocks is determined using the following expression:

where

—quantity of exploited rock mass from the n-th productive layer,

—recovery coefficient of the deposit for the n-th productive layer.

The costs of surface exploitation

consist of the costs of exploiting the productive layers

, as well as the costs of exploiting the low wall

and the overburden

. The overburden and the low wall are considered waste rock and will not be valued during the economic analysis. The costs of surface overburden removal and the costs of low wall exploitation can be presented together as the cost of waste rock exploitation

:

where

—cost of waste rock exploitation (EUR),

—cost of surface overburden removal (EUR),

—cost of low wall exploitation (EUR).

The total costs of surface exploitation can be represented as the sum of waste rock removal costs

, DS exploitation costs

, and land reclamation costs

, as shown in the following expression:

where

—total costs of surface DS exploitation (EUR),

—exploitation costs for DS (EUR),

—waste rock removal costs (EUR),

—land reclamation costs (EUR).

The total costs of underground exploitation consist of the costs of exploiting the productive DS layers and overburden and low wall.

In underground exploitation of DS, overburden and low walls are considered as waste rock that must be exploited during the exploitation of the DS layer. Analogous to surface exploitation, the costs of overburden removal

and the costs of low wall exploitation

can be collectively represented as the costs of waste rock exploitation

:

where

—cost of waste rock exploitation (EUR),

—cost of underground overburden removal (EUR),

—cost of low wall exploitation (EUR).

The costs of underground exploitation

can be represented as the sum of the costs of waste rock exploitation

and the costs of exploiting the productive DS layers

. The costs of land reclamation are entirely omitted, resulting in the following expression:

where

—total costs of underground DS exploitation (EUR),

—exploitation costs for DS (EUR),

—underground waste rock exploitation costs (EUR).

Through a comparative analysis of the profit from surface and underground exploitation, it is possible to determine the position of the optimal exploitation contour, that is, the location of the optimal transition point from surface to underground exploitation.

5. Conclusions

One of the challenges in DS exploitation is adapting the exploitation method to the deposit conditions; thus, the same deposit can be exploited by surface, underground, or even a combined method. Given that both exploitation methods differ in their approach and that various techno-economic factors affect each method to different extents, it is essential to accurately define the point at which it is necessary to switch from surface to underground exploitation should the deposit conditions require it.

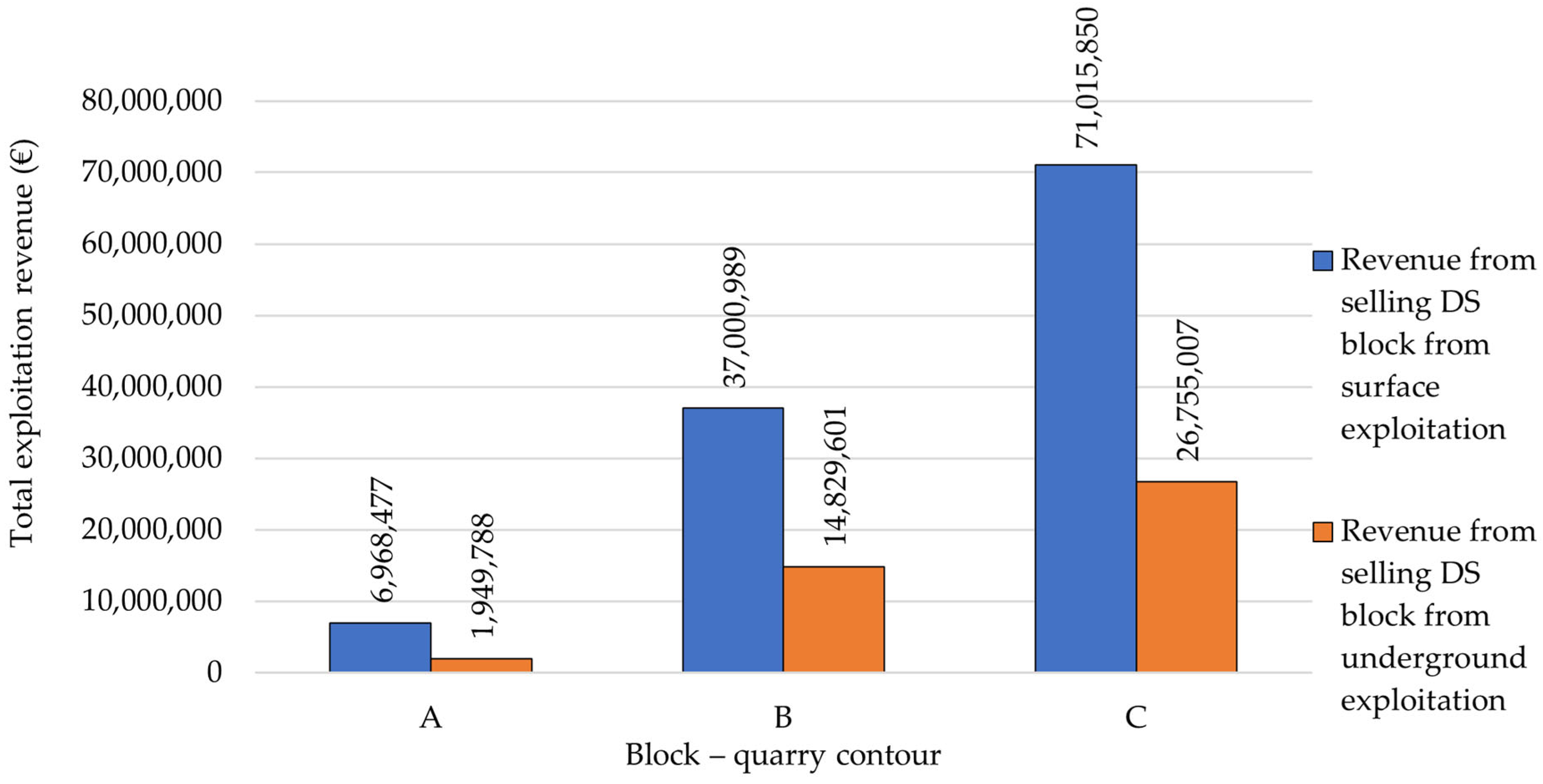

To determine the optimal exploitation method for DS based on the location of mining activities, a research model was selected. Three optimisation model blocks (A, B, and C) were identified, each of which was analysed for the possibility of applying both exploitation methods.

A comprehensive analysis of techno-economic factors—including recovery rates, exploitation costs, revenue generated from the sale of DS blocks, and overall profit—was conducted for each block to determine the optimal transition point (OTP) from surface to underground quarry exploitation. When assessing these techno-economic factors, it is essential to adapt them to the specific conditions present within the deposit, as well as to the prevailing economic circumstances at the location where the method is to be applied.

The DS-EOM method is specifically designed for the determination of the optimal transition point between surface and underground exploitation in dimension stone (DS) deposits. Its application is most effective in deposits where both exploitation methods are technically feasible and where there is sufficient geological, geometric, and economic data to support detailed techno-economic analysis. The method is applicable regardless of the specific lithology or geometry of the DS deposit, provided that the deposit can be discretised into blocks for comparative evaluation. However, the accuracy and reliability of the DS-EOM approach are contingent upon the quality and resolution of input data, as well as the appropriateness of the economic parameters used. The method may be less suitable for deposits with highly irregular geometries or complex tectonic settings or where the economic or technical feasibility of either exploitation method is fundamentally constrained.

Furthermore, as an opportunity for further research, development, and application of this method, a software solution could be created that would enable the new methodology to be efficiently, quickly, simply, and accurately applied depending on deposit conditions. Additionally, the accuracy of the method can be further improved by introducing additional blocks in the analysis. This refinement would allow for a more precise determination of the optimal transition point (OTP), ensuring that the shift from surface to underground exploitation is identified with greater exactness.