Common Pitfalls and Recommendations for Use of Machine Learning in Depression Severity Estimation: DAIC-WOZ Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- How reliable, reproducible, and methodologically rigorous are published machine learning models?

- RQ2:

- What are the most common methodological flaws present in current machine learning research?

- RQ3:

- Are there specific practices that systematically lead to the overestimation or misrepresentation of machine learning models’ performance?

- RQ4:

- How does subject leakage between training and evaluation partitions affect the measured performance of machine learning models?

- RQ5:

- What recommendations can be made to improve the methodological rigor, reproducibility, and documentation standards for future machine learning research?

2. Methods

- The study reported experimental results on the DAIC-WOZ dataset.

- The evaluation metrics for regression of depression severity scores included MAE.

- The study presents scientific novelty; studies that solely repurposed or applied existing methods without introducing methodological innovation were excluded.

- The study was published in English.

- Clear description of data preprocessing steps;

- Explicit reporting of data partitioning scheme (proportions, partitions disjoint levels);

- Detailed model description, including architecture, inputs, outputs, and intermediate layers;

- Specification of training details (data augmentation, hyperparameters, number of models trained);

- Method for selecting the final model.

3. Results

- Not addressing the DAIC-WOZ dataset ();

- Not reporting MAE as an evaluation metric ();

- Not introducing a new model or repurposing an existing model ();

- Not written in English ().

- Data partitioning: 37.9% (), including the following:

- Training details: 71.2% () [14,15,16,17,18,19,21,23,25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,36,37,38,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. We additionally stratify this number by the publication venue, as stricter page limits for conference papers lead to different documentation expectations compared to journal articles. Of the 47 studies with insufficient training details, 25 were conference papers and 22 were journal articles.

- In total, 81.8% () of the studies do not use repeated experiments and instead rely on a single experimental run [13,14,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,58,59,60,61,62,64,65,67,69,70,71,73,76,77,78]. This is a critical flaw, as many computational methods in machine learning involve stochastic elements such as random initialization, data shuffling, or sampling. Without running experiments multiple times and reporting measures of variability (e.g., mean and standard deviation (SD) over different seeds or cross-validation folds), the reported performance lacks statistical validity.

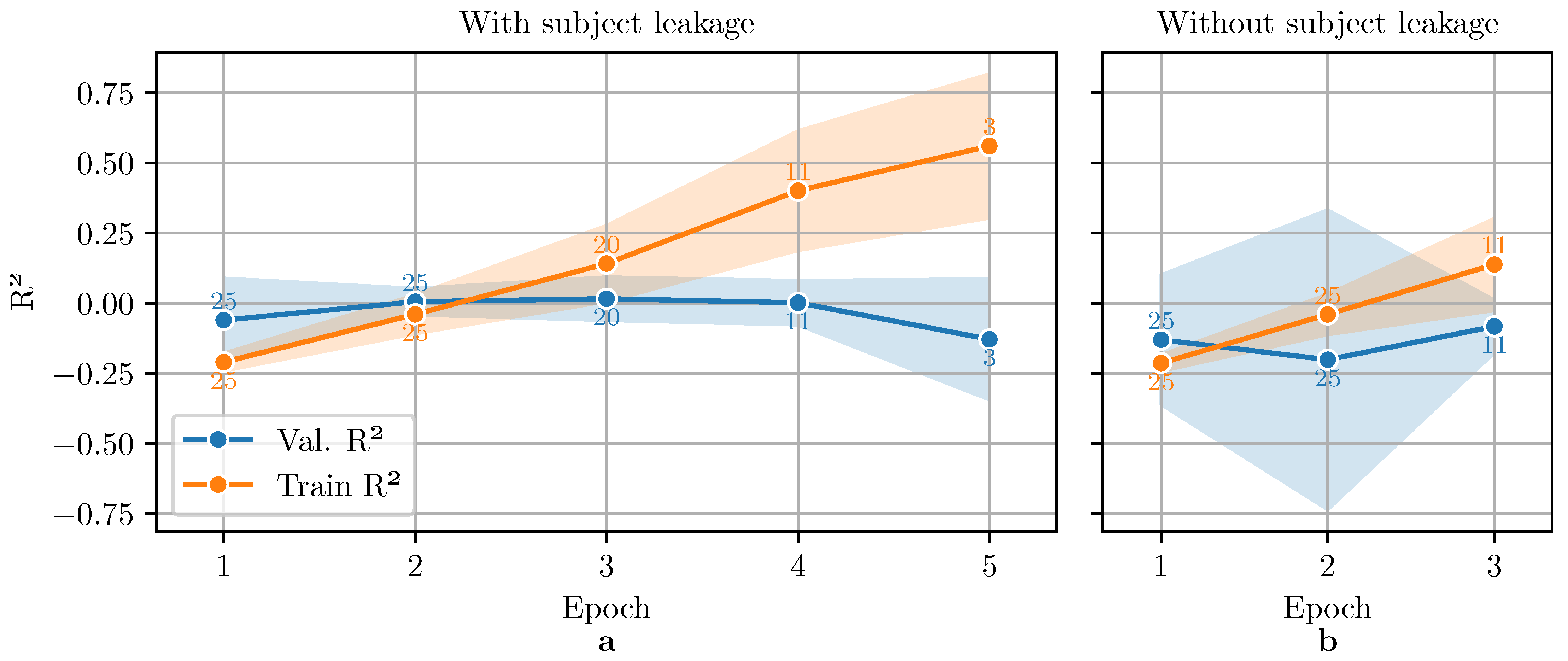

- The vast majority of the studies report measures of errors such as MAE and RMSE, while completely ignoring goodness-of-fit metrics such as coefficient of determination (). Although useful, MAE and RMSE have no upper bound and do not provide information about the performance of the regression with respect to the distribution of the ground truth values. In contrast, quantifies the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that the model predicts from the independent variables [79]. Without or a similar measure of explained variance, it is difficult to assess whether low prediction errors reflect genuine variance explained by the model or are a consequence of the target variable’s scale. ( has its own limitations. Due to its definition (see Equation (2)), direct comparisons of across datasets with differing variance in the dependent variable are problematic. may also be less informative when residuals or the dependent variable are non-normally distributed. Nevertheless, it provides a useful measure of the proportion of variance explained by the model within a given dataset.) Yet only 6.1% () of the studies additionally report [17,26,61,63].

- Only 30.3% () of the studies report performance on a held-out test set [28,31,41,44,45,49,52,53,54,59,63,64,68,69,71,72,73,74,76,77], while the rest evaluate models solely on the validation set. Relying on the validation set only can lead to the overly optimistic results, as this set is often used for model selection (early stopping on validation loss, best validation performance, etc.) or hyperparameter tuning, and is a form of inadvertent overfitting.

- It has been shown for DAIC-WOZ that incorporating interviewer turns into the feature set leads to inflated performance estimates. Burdisso et al. [80] demonstrated that models trained solely on interviewer prompts achieve equal or higher performance than those trained on participant responses, indicating that interviewer turns in the DAIC-WOZ dataset act as discriminative shortcuts rather than clinically meaningful signals. Although the actual evidence is limited to the textual modality, a similar effect may plausibly occur in the audio modality, since the transcripts are extracted directly from the audio recordings. This may potentially constitute a methodological pitfall in 42.4% () of the studies, as they incorporate interviewer utterances as input data [18,19,24,32,33,36,37,39,40,41,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,58,60,63,68,71,72,73,74,75,76] (due to the underreported data preprocessing procedures in some of the papers, data on the use of interviewer turns are missing for 25.8% () of the studies).

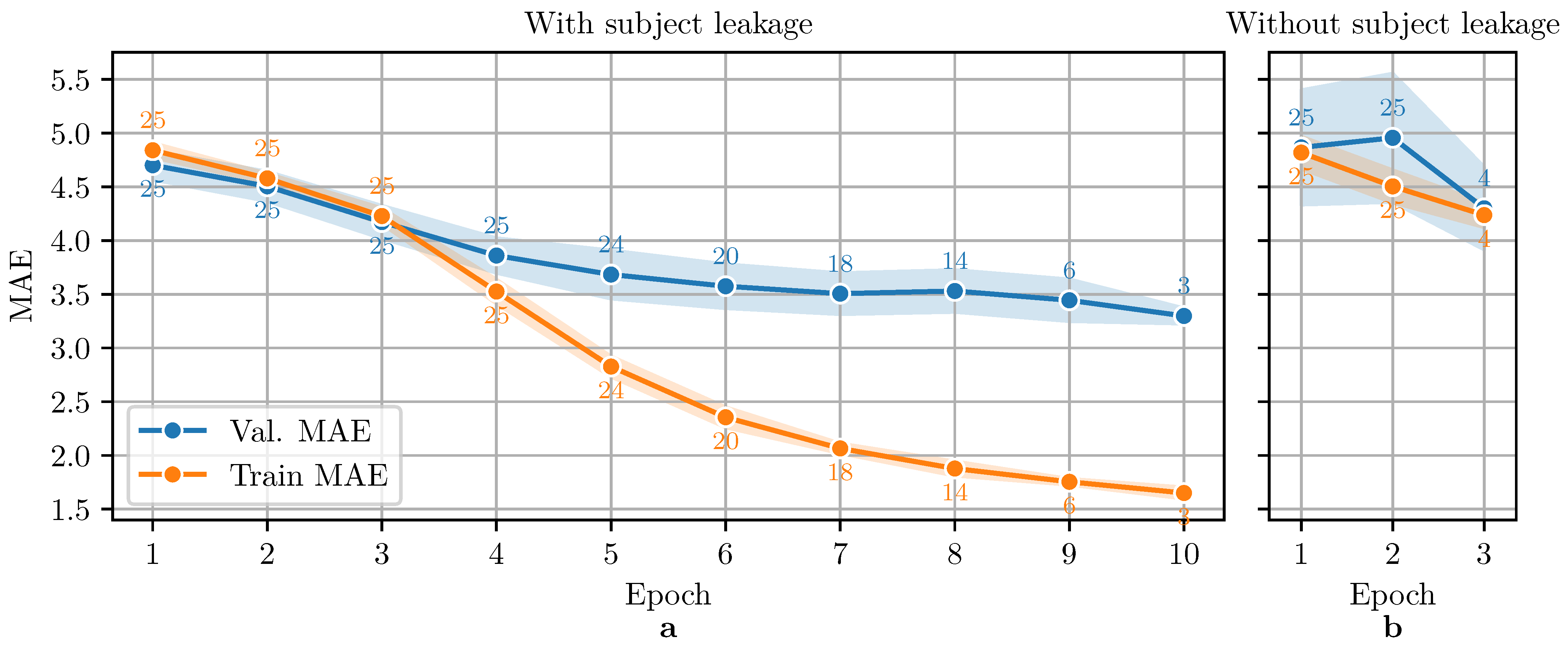

- At least 9.1% () of the studies exhibit subject leakage [32,34,55,56,60,70], while an additional 24.2% () could not be confirmed due to the insufficient documentation of data preprocessing procedures. Subject leakage occurs when data partitions are disjoint at a level more granular than the interview (e.g., at the level of 30 s audio clips, individual participant turns, etc.), and random splits are applied after such preprocessing. This results in the same participant contributing data to both training and evaluation partitions, allowing models to exploit subject-specific cues rather than learning generalizable patterns.

4. Empirical Demonstration of Subject Leakage Pitfall

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Data Preprocessing

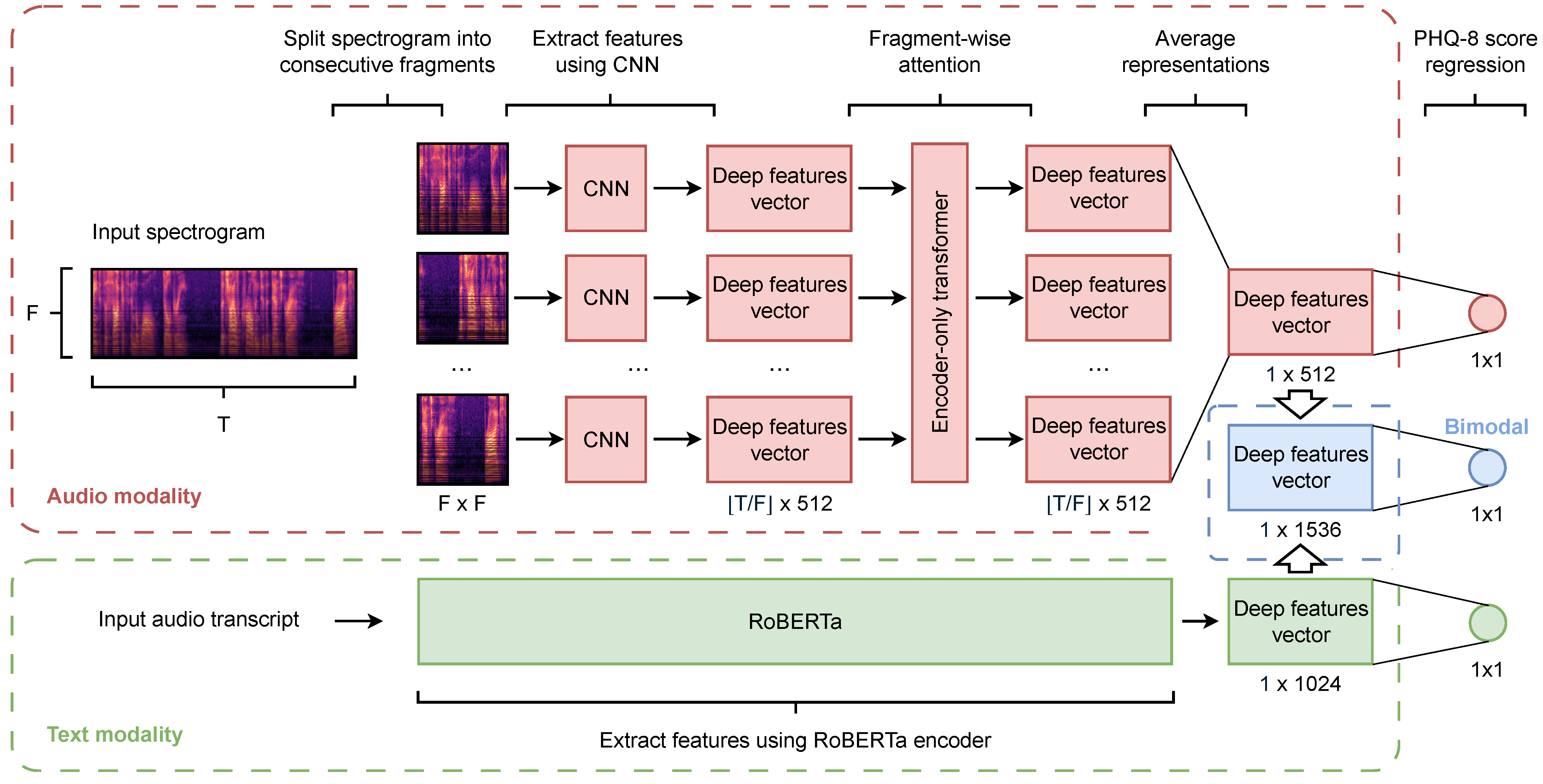

4.3. Model Architecture

4.4. Training Procedure

4.5. Impact of Subject Leakage on Model Performance

5. Discussion

- i.

- Reporting results from a single experimental run is prone to misrepresenting the actual performance due to the stochasticity in machine learning.

- ii.

- The lack of tests on held-out data causes inadvertent overfitting to validation data.

- iii.

- The most prevalent choice for the evaluation metric in the literature related to depression severity estimation is MAE. This is often accompanied by RMSE and MSE used as an optimization criterion. While MSE is a good choice as a cost function for model training, it and its rooted variant RMSE do not quantify errors in an easily interpretable way. MAE directly translates to the scale of actual labels and therefore is easier to interpret. Nevertheless, all three metrics share common limitations of not having an upper bound and not explaining how well the model fits the data. We strongly encourage researchers to incorporate into their evaluation procedures. in the [0, 1] interval directly indicates the fraction of variance explained by the model, while its negative value means that the regression fits worse than the mean predictor. Furthermore, is monotonically related to MSE (Equation (2)). This means that the ordering of the regression models based on the coefficient of determination will be identical to an ordering of models based on MSE or RMSE [79]. Our model, trained without subject leakage on the audio modality of DAIC-WOZ, achieved MAE (val.: , test: ) comparable to the models included in this review. Relying on MAE alone would misleadingly suggest success, whereas negative clearly indicates that the model fails to generalize to unseen data.

- i.

- For the textual modality of the DAIC-WOZ, the model trained on interviewer prompts yields better performance than the one trained on participant responses [80]. This flaw is specific to the DAIC-WOZ text modality, although it is possible that this may have similar effects to the other modalities of the dataset. We therefore recommend authors to explicitly state whether interviewer turns are included in the inputs of the model and justify their use. The best results included in our review (val. MAE of [75] and test MAE of [76]) were reported by studies that used text modality and incorporated interviewer prompts.

- ii.

- In our study, we examined the impact of subject leakage on the validation set and showed that this results in a substantive performance overestimation on audio, text, and combined modality of the DAIC-WOZ dataset. This effect cannot be diagnosed without evaluation on the held-out set with unseen participants. In the following paragraph, we discuss the results of our empirical experiments.

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

References

- World Health Organization. Depression: Let’s Talk Says WHO, as Depression Tops List of Causes of Ill Health. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017–depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Paykel, E.S.; Priest, R.G. Recognition and management of depression in general practice: Consensus statement. BMJ 1992, 305, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringaris, A. Editorial: What is depression? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1287–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Xie, G.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Shao, G.; Lv, B.; Jing, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Automatic depression diagnosis through hybrid EEG and near-infrared spectroscopy features using support vector machine. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1205931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kumbale, S.; Chen, Y.; Surana, T.; Chng, E.S.; Guan, C. Automated Depression Detection from Text and Audio: A Systematic Review. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Rahman Ahad, M.A.; Ren, M.; Yao, L.; Huang, Y. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Depressive Disorders via Various Data Modalities: A Survey. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2025, 12, 1320–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J. A systematic review on automated clinical depression diagnosis. npj Ment. Health Res. 2023, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratch, J.; Artstein, R.; Lucas, G.; Stratou, G.; Scherer, S.; Nazarian, A.; Wood, R.; Boberg, J.; DeVault, D.; Marsella, S.; et al. The Distress Analysis Interview Corpus of human and computer interviews. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14), Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–31 May 2014; pp. 3123–3128. [Google Scholar]

- Ringeval, F.; Schuller, B.; Valstar, M.; Cummins, N.; Cowie, R.; Tavabi, L.; Schmitt, M.; Alisamir, S.; Amiriparian, S.; Messner, E.M.; et al. AVEC 2019 Workshop and Challenge: State-of-Mind, Detecting Depression with AI, and Cross-Cultural Affect Recognition. In Proceedings of the 9th International on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge and Workshop, New York, NY, USA, 21 October 2019; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugwell, P.; Tovey, D. PRISMA 2020. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, A5–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, J.; Moy, L.; Kahn, C.E., Jr. Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): A Guide for Authors and Reviewers. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e200029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Li, M.; Fu, C. PointTransform Networks for automatic depression level prediction via facial keypoints. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 297, 111951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Peng, S.; Liang, Y.; Hung, C.C.; Liu, S. A multimodal fusion model with multi-level attention mechanism for depression detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 82, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, A.; El Sayad, D.; Ezzat, D.; Amin, S.; El Gamal, M. Speech-Based Depression Detection System Optimized Using Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th Novel Intelligent and Leading Emerging Sciences Conference (NILES), Giza, Egypt, 19–21 October 2024; pp. 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, T.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X. Gaze Behavior based Depression Severity Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 4th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (PRML), Urumqi, China, 4–6 August 2023; pp. 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoz, N.; Beresteneva, O.G.; Aksyonov, S.V. Enhancing Depression Detection: Employing Autoencoders and Linguistic Feature Analysis with BERT and LSTM Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon), Sochi, Russia, 10–16 September 2023; pp. 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.R.; Godoy, E.; Cha, M.; Schwarzentruber, A.; Khorrami, P.; Gwon, Y.; Kung, H.T.; Dagli, C.; Quatieri, T.F. Detecting Depression using Vocal, Facial and Semantic Communication Cues. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 16 October 2016; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, J.; Lu, H.; Guo, M.; Chen, S. Rethinking Inconsistent Context and Imbalanced Regression in Depression Severity Prediction. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2024, 15, 2154–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Chaspari, T. Robust and Explainable Depression Identification from Speech Using Vowel-Based Ensemble Learning Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), Houston, Texas, USA, 10–13 November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoz, N. Detecting Depression from Text: A Gender Based Comparative Approach Using Machine Learning and BERT Embeddings. In Proceedings of the 20th All-Russian Conference of Student Research Incubators, Tomsk, Russia, 10–16 September 2023; pp. 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Iyortsuun, N.K.; Kim, S.H.; Yang, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Jhon, M. Additive Cross-Modal Attention Network (ACMA) for Depression Detection Based on Audio and Textual Features. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 20479–20489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Hu, B.; Qian, W.; Guo, D.; Wang, M. Facial Depression Estimation via Multi-Cue Contrastive Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 6007–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkel, H.; Wu, M.; Yu, K. Text-based depression detection on sparse data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.05154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, K. Unaligned Multimodal Sequences for Depression Assessment From Speech. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 3409–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoz, N.; Beresteneva, O.G.; Vladimirovich, A.S.; Tahsin, M.S. Enhancing depression detection through advanced text analysis: Integrating BERT, autoencoder, and LSTM models. Res. Sq. Platf. LLC 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangyao, S.; Shenghui, Z.; Bochao, Z.; Yubo, A. Multimodal depression detection using a deep feature fusion network. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Computer Science and Communication Technology, ICCSCT 2022, Beijing, China, 30–31 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Wang, X.; Gong, J.; Liu, B.; Tao, J.; Schuller, B.W. Depression Scale Dictionary Decomposition Framework for Multimodal Automatic Depression Level Prediction. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 6195–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Yan, L.; Gou, C.; Wang, F.Y. Graph Attention Model Embedded with Multi-Modal Knowledge for Depression Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME 2020), London, United Kingdom, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TJ, S.J.; Jacob, I.J.; Mandava, A.K. D-ResNet-PVKELM: Deep neural network and paragraph vector based kernel extreme machine learning model for multimodal depression analysis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 25973–26004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Li, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhou, X.; Schuller, B.W. DepressionMLP: A Multi-Layer Perceptron Architecture for Automatic Depression Level Prediction via Facial Keypoints and Action Units. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 8924–8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Shu, J. Depression detection methods based on multimodal fusion of voice and text. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, D.; Jung, J. LEFORMER: Liquid Enhanced Multimodal Learning for Depression Severity Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 38th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS 2025), Madrid, Spain, 18–20 June 2025; pp. 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Misra, S.; Shao, Z.; Zhu, B.; Raman, B.; Li, X. Multimodal Interpretable Depression Analysis Using Visual, Physiological, Audio and Textual Data. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV 2025), Tucson, Arizona, USA, 28 February–4 March 2025; pp. 5305–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, W. Multi-level spatiotemporal graph attention fusion for multimodal depression detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 110, 108123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Bao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cummins, N.; Wang, H.; Schuller, B. Hierarchical Attention Transfer Networks for Depression Assessment from Speech. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP 2020), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 7159–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Dhamaniya, A.; Gupta, P. RADIANCE: Reliable and interpretable depression detection from speech using transformer. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 183, 109325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, B.; Lian, Z.; Cai, C.; Tao, J.; Zhao, Z. Prediction of Depression Severity Based on Transformer Encoder and CNN Model. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing (ISCSLP), Singapore, 11–14 December 2022; pp. 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, D.; Lou, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, S.; Yu, J.; Xiao, J. Text-guided multimodal depression detection via cross-modal feature reconstruction and decomposition. Inf. Fusion 2025, 117, 102861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Diao, G. Recognition of Audio Depression Based on Convolutional Neural Network and Generative Antagonism Network Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 101181–101191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Guo, Q.; Sun, W.; Shang, Y. A Layered Multi-Expert Framework for Long-Context Mental Health Assessments. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 5–7 May 2025; pp. 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.C.; Peng, K.; Roitberg, A.; Yang, K.; Zhang, J.; Stiefelhagen, R. Multi-modal Depression Estimation Based on Sub-attentional Fusion. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022 Workshops, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2023; pp. 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanggala, K.; Elwirehardja, G.N.; Pardamean, B. Depression detection through transformers-based emotion recognition in multivariate time series facial data. Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2025, 14, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Lu, R. Neural Architecture Searching for Facial Attributes-based Depression Recognition. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 21–25 August 2022; pp. 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; He, L.; Pei, E.; Oveneke, M.C.; Sahli, H. Decision Tree Based Depression Classification from Audio Video and Language Information. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 16 October 2016; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, L. Towards automatic depression detection: A BiLSTM/1D CNN-based model. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasipuram, S.; Bhat, J.H.; Maitra, A.; Shaw, B.; Saha, S. Multimodal Depression Detection Using Task-oriented Transformer-based Embedding. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Rhodes Island, Greece, 30 June–3 July 2022; pp. 01–04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Chan, W.Y.; Zhu, X. Improving Depression Assessment with Multi-Task Learning from Speech and Text Information. In Proceedings of the 55th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 31 October–3 November 2021; pp. 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohanian, M.; Hough, J.; Purver, M. Detecting Depression with Word-Level Multimodal Fusion. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2019, Graz, Austria, 15–19 September 2019; pp. 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakrankamanant, P.; Watanabe, S.; Chuangsuwanich, E. Explainable Depression Detection using Masked Hard Instance Mining. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.24609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, A.; Xie, Q.; Ma, H.; Li, Z.; Guo, D. Agentmental: An interactive multi-agent framework for explainable and adaptive mental health assessment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.11567. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Shao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Niu, M.; Chen, H.; Hu, Q.; Wu, J.; et al. TTFNet: Temporal-Frequency Features Fusion Network for Speech Based Automatic Depression Recognition and Assessment. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 7536–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, Y. Multilevel depression status detection based on fine-grained prompt learning. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2024, 178, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Yu, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, Z. A Random Forest Regression Method With Selected-Text Feature For Depression Assessment. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, New York, NY, USA, 23 October 2017; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, R. An automatic diagnostic network using skew-robust adversarial discriminative domain adaptation to evaluate the severity of depression. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019, 173, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, W.; Wu, Q. Autoencoder Based on Cepstrum Separation to Detect Depression from Speech. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information Technologies and Electrical Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 14–15 September 2021; pp. 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mao, K.; Chen, J. A Multimodal approach for detection and assessment of depression using text, audio and video. Phenomics 2024, 4, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Chen, K.; Chen, Q.; Yang, L. HCAG: A Hierarchical Context-Aware Graph Attention Model for Depression Detection. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 4235–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Sahli, H.; Xia, X.; Pei, E.; Oveneke, M.C.; Jiang, D. Hybrid Depression Classification and Estimation from Audio Video and Text Information. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, New York, NY, USA, 23 October 2017; pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, M.; Okada, Y.; Uchiyama, R.; Horiguchi, R.; Toyoshima, I. A new regression model for depression severity prediction based on correlation among audio features using a graph convolutional neural network. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Shang, Y. Advancing Mental Health Pre-Screening: A New Custom GPT for Psychological Distress Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Cognitive Machine Intelligence (CogMI), Washington, DC, USA, 28–31 October 2024; pp. 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oureshi, S.A.; Dias, G.; Saha, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Gender-Aware Estimation of Depression Severity Level in a Multimodal Setting. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Shenzhen, China, 18–22 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.A.; Dias, G.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Saha, S. Improving Depression Level Estimation by Concurrently Learning Emotion Intensity. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2020, 15, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; An, N. Parallel Multiscale Bridge Fusion Network for Audio–Visual Automatic Depression Assessment. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 6830–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Li, W.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. Encoding Visual Behaviors with Attentive Temporal Convolution for Depression Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019), Lille, France, 14–18 May 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Shen, L.; Valstar, M. Human Behaviour-Based Automatic Depression Analysis Using Hand-Crafted Statistics and Deep Learned Spectral Features. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018), Xi’an, China, 15–19 May 2018; pp. 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; Sahli, H. Feature Augmenting Networks for Improving Depression Severity Estimation From Speech Signals. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 24033–24045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Poellabauer, C. Topic Modeling Based Multi-modal Depression Detection. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, New York, NY, USA, 23 October 2017; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shao, S.; Milling, M.; Schuller, B.W. Large language models for depression recognition in spoken language integrating psychological knowledge. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 7, 1629725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, S.; Bharathi, V.C. Se-GCaTCT: Correlation based optimized self-guided cross-attention temporal convolutional transformer for depression detection with effective optimization strategy. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2026, 112, 108561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Teng, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Y. SIMMA: Multimodal Automatic Depression Detection via Spatiotemporal Ensemble and Cross-Modal Alignment. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2025, 12, 3548–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhou, H.; Ba, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, G. Improving depression prediction using a novel feature selection algorithm coupled with context-aware analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Shang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Liu, J.; Guo, G.; Liu, T.; Ding, H.; Hu, Q. Spatial–Temporal Feature Network for Speech-Based Depression Recognition. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2024, 16, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milintsevich, K.; Sirts, K.; Dias, G. Towards automatic text-based estimation of depression through symptom prediction. Brain Inform. 2023, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Cohn, A.; Hogg, D. Using graph representation learning with schema encoders to measure the severity of depressive symptoms. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Online, 25–29 April 2022; Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/186629/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Kang, A.; Chen, J.Y.; Lee-Youngzie, Z.; Fu, S. Synthetic Data Generation with LLM for Improved Depression Prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.17672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Z.S.; Sidorov, K.; Marshall, D. Depression Severity Prediction Based on Biomarkers of Psychomotor Retardation. In Proceedings of the AVEC ’17: 7th Annual Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, New York, NY, 23 October 2017; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, S.; Kaur, B.; Agrawal, R.K. Enhanced Depression Detection from Facial Cues Using Univariate Feature Selection Techniques. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Machine Intelligence, Kolkata, India, 17–20 December 2019; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdisso, S.; Reyes-Ramírez, E.; Villatoro-tello, E.; Sánchez-Vega, F.; Lopez Monroy, A.; Motlicek, P. DAIC-WOZ: On the Validity of Using the Therapist’s prompts in Automatic Depression Detection from Clinical Interviews. In Proceedings of the 6th Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop, Mexico City, Mexico, 21 June 2024; pp. 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degottex, G.; Kane, J.; Drugman, T.; Raitio, T.; Scherer, S. COVAREP—A collaborative voice analysis repository for speech technologies. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Florence, Italy, 4–9 May 2014; pp. 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazy, L.; Grote, M.; Liegl, G.; Rose, M.; Fischer, F. Cross-Sectional Reference Data From 29 European Countries for 6 Frequently Used Depression Measures. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2517394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, S.S.; Ntalampiras, S.; Sassi, R. Speech-Based Depression Assessment: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2025, 16, 1318–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Kim, J.; Yu, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, K. Self-supervised transfer learning from natural images for sound classification. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Valstar, M.; Schuller, B.; Smith, K.; Eyben, F.; Jiang, B.; Bilakhia, S.; Schnieder, S.; Cowie, R.; Pantic, M. AVEC 2013: The continuous audio/visual emotion and depression recognition challenge. In Proceedings of the AVEC ’13: 3rd ACM International Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, New York, NY, USA, 21 October 2013; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, M.; Ehghaghi, M.; Diep, B.; Novikova, J. DEPAC: A Corpus for Depression and Anxiety Detection from Speech. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.12443. [Google Scholar]

| Approach | Data Modality | Model | Val. MAE | Test MAE | Repeated Experiments | Uses Interviewer’s Prompts | Subject Leakage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milintsevich et al. [74] | T | RoBERTa-BiLSTM | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ||

| Syed et al. [77] | V–A | Fisher Vectors, PLSR | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Hong et al. [75] | T | GNN | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Rathi et al. [78] | V | Linear Regression | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Kang et al. [76] | T | BERT | — | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Ours (no leakage) | A | CNN-Transformer | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Ours (no leakage) | T | RoBERTa | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Ours (no leakage) | A–T | CNN-Transformer, RoBERTa | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Modality | Metric | Subject Leakage | Val. | Test (Heldout, No Leakage) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | False | |||

| True | ||||

| MAE | False | |||

| MAE | True | |||

| T | False | |||

| True | ||||

| MAE | False | |||

| MAE | True | |||

| A-T | False | |||

| True | ||||

| MAE | False | |||

| MAE | True |

| Modality | Metric | 95% CI | Shapiro p | Test | p | Cohen’s d | Adj. p (Holm) | Significant | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Val. | [, ] | Wilcoxon | ✓ | |||||

| Test | [, ] | t-test | ✓ | ||||||

| Val. MAE | [, ] | t-test | ✓ | ||||||

| Test MAE | [, ] | t-test | ✓ | ||||||

| T | Val. | [, ] | Wilcoxon | ✓ | |||||

| Test | [, ] | t-test | ✗ | ||||||

| Val. MAE | [, ] | t-test | ✗ | ||||||

| Test MAE | [, ] | t-test | ✗ | ||||||

| A-T | Val. | [, ] | Wilcoxon | ✓ | |||||

| Test | [, ] | t-test | ✗ | ||||||

| Val. MAE | [, ] | t-test | ✓ | ||||||

| Test MAE | [, ] | t-test | ✗ |

| Aspect | Item # | Checklist Item |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Requirements | ||

| Methodology | 1 | Use a data partitioning scheme with partitions disjoint at the participant to prevent subject leakage across training, validation, and test sets. |

| 2 | Preserve a held-out test set with unseen participants and report test performance separately from validation results. | |

| 3 | Incorporate into the evaluation protocol as a primary goodness-of-fit metric, in addition to error metrics such as MAE or RMSE. | |

| 4 | Train and validate models in cross-validation schemes or other forms of repeated experiments whenever applicable. | |

| 5 | Report metrics variability (e.g., standard deviation) across repeated experiments. | |

| Documentation | 6 | Explicitly document the adopted methodology—describe in detail all steps from data preprocessing through training and evaluation to final model selection, including (where applicable), but not limited to, data cleaning and augmentation, training objective and hyperparameters, best model selection objective, and number of models trained. |

| 7 | Provide a complete description of the model architecture (i.e., number of layers, dimensionalities, etc.). | |

| Best Practices | ||

| Model diagnostics | 8 | Report the model’s calibration curve or error distribution plots to visualize the model’s errors with respect to the ground truth labels. |

| 9 | Conduct ablation studies where applicable. | |

| Reproducibility | 10 | Make source code with frozen dependency versions publicly available for each part of the study, including model training, evaluation, and statistical analysis of the results. |

| 11 | Ensure accessibility of each experimental run outputs (e.g., logs, metrics, checkpoints). | |

| 12 | Employ containerized environments (e.g., Docker) for your experiments to ensure portability and long-term reproducibility. | |

| 13 | Use open-source experiment tracking tools (e.g., MLFlow) to foster experimentation and further ease of adoption. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Danylenko, I.; Unold, O. Common Pitfalls and Recommendations for Use of Machine Learning in Depression Severity Estimation: DAIC-WOZ Study. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010422

Danylenko I, Unold O. Common Pitfalls and Recommendations for Use of Machine Learning in Depression Severity Estimation: DAIC-WOZ Study. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010422

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanylenko, Ivan, and Olgierd Unold. 2026. "Common Pitfalls and Recommendations for Use of Machine Learning in Depression Severity Estimation: DAIC-WOZ Study" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010422

APA StyleDanylenko, I., & Unold, O. (2026). Common Pitfalls and Recommendations for Use of Machine Learning in Depression Severity Estimation: DAIC-WOZ Study. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010422