A Physical Modeling Method for the Bulking–Compaction Behavior of Rock Mass in the Caving Zone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

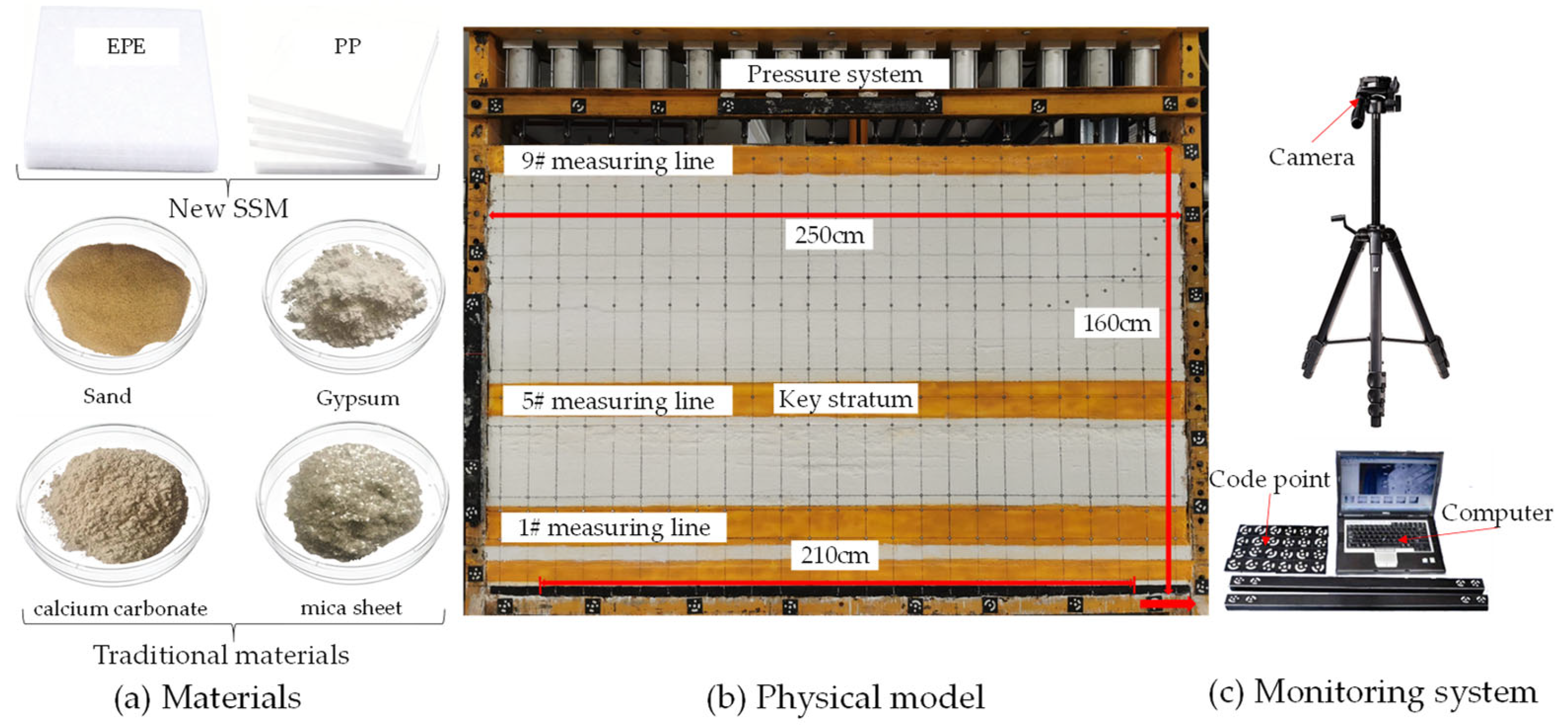

2.1. New Similar Simulation Material of the Caving Zone

2.2. Orthogonal Experimental Design

2.3. Experimental Methods

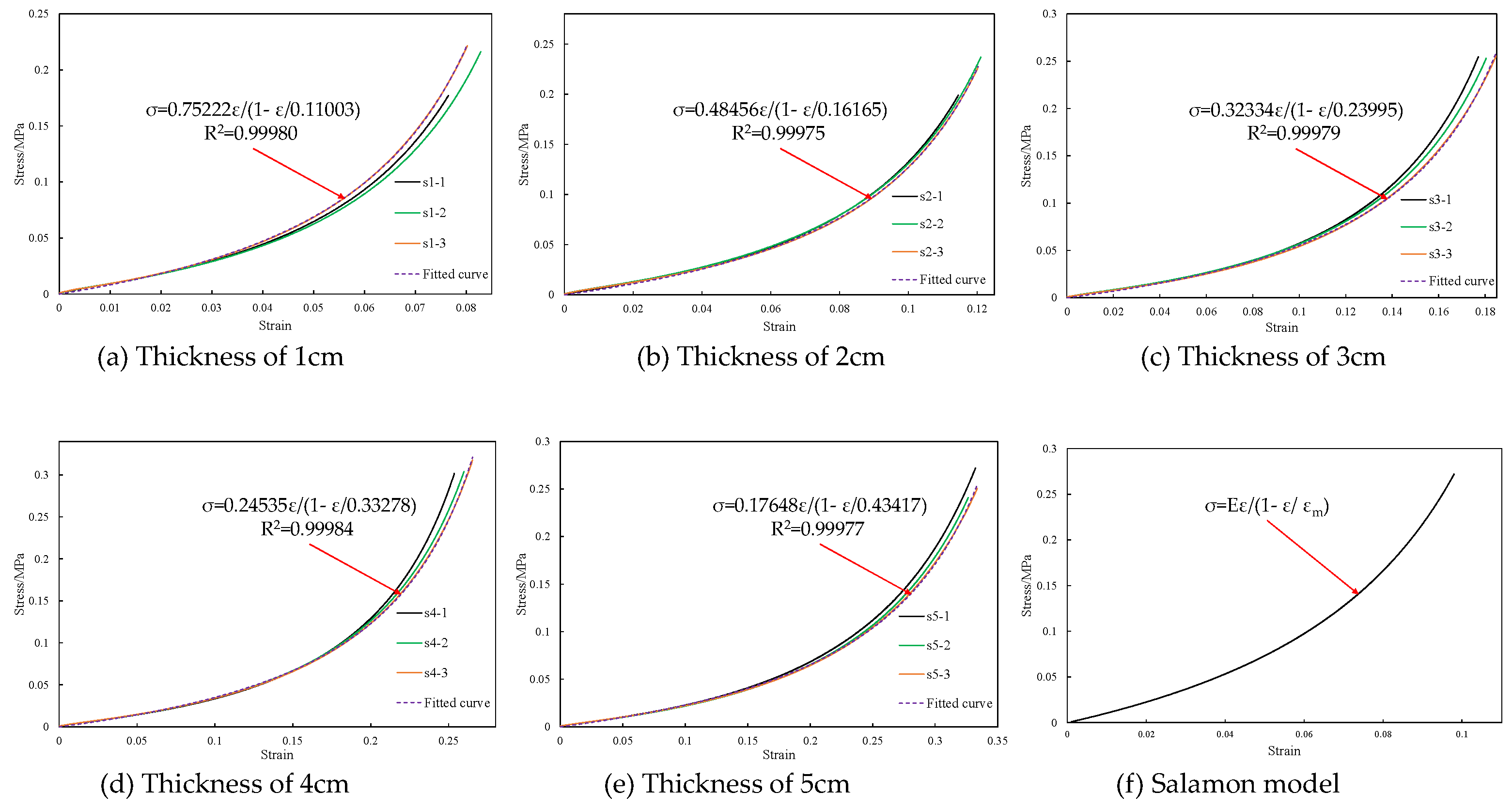

3. Orthogonal Experimental Results

4. Verification by Physical Similarity Modeling

4.1. Physical Simulation Experimental Program

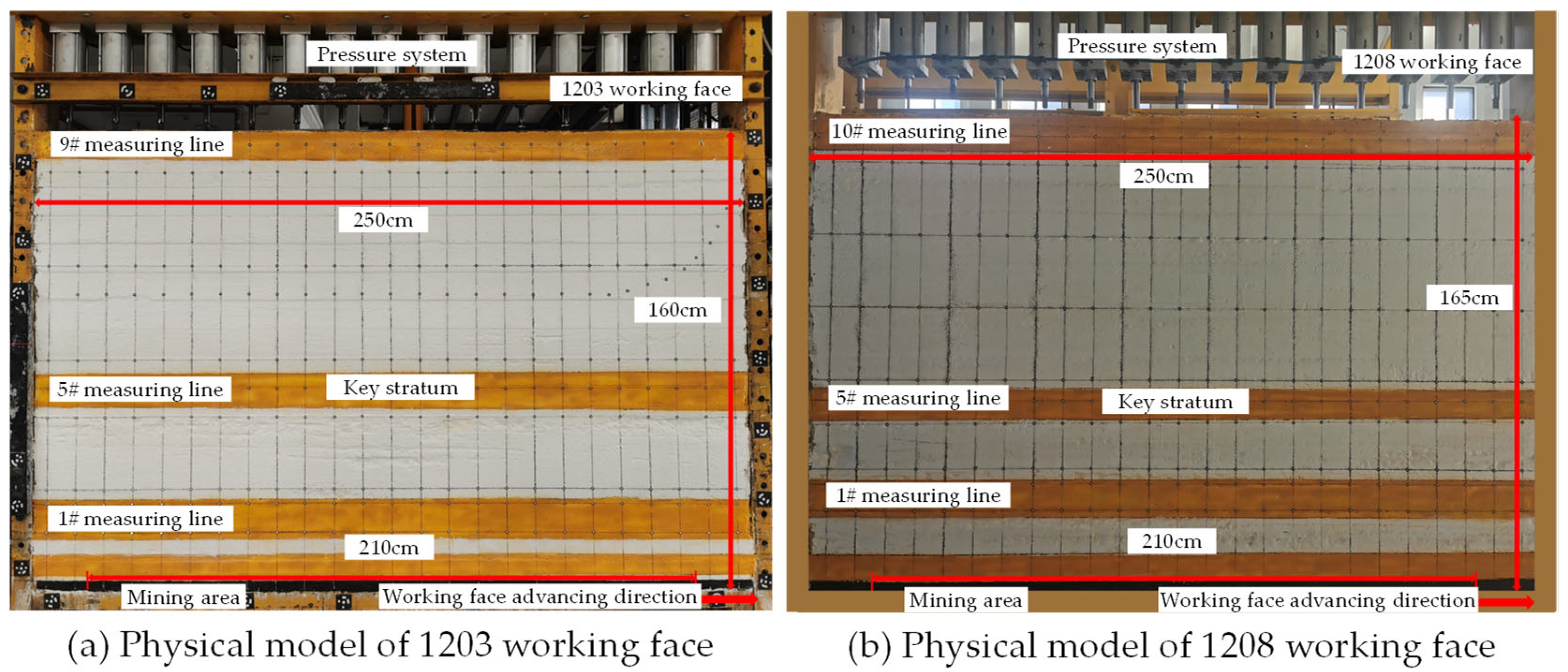

4.1.1. Physical Simulation Model

4.1.2. Determination of the New SSM Dimensions

4.2. Materials and Methods for Physical Modeling

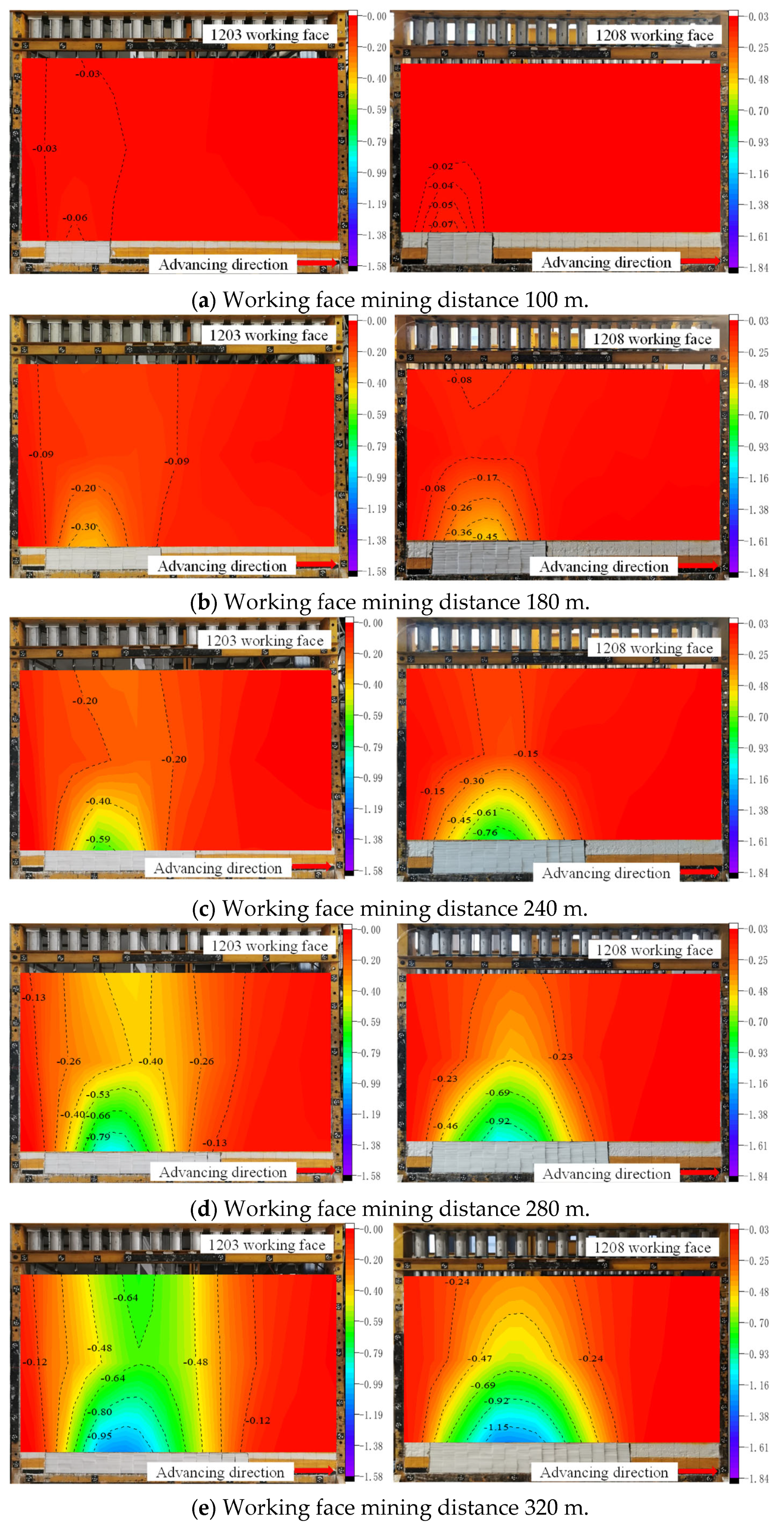

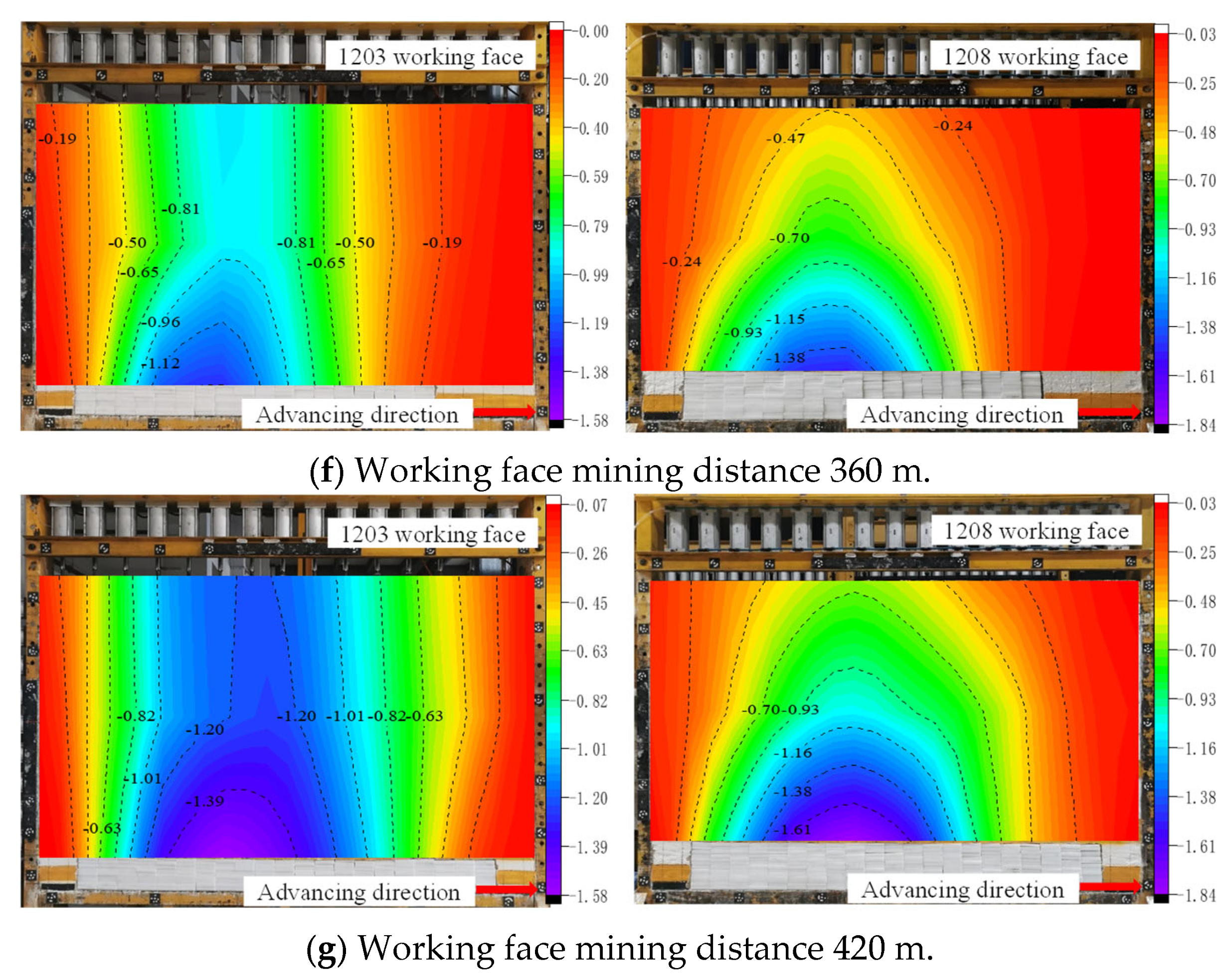

4.3. Physical Simulation Results

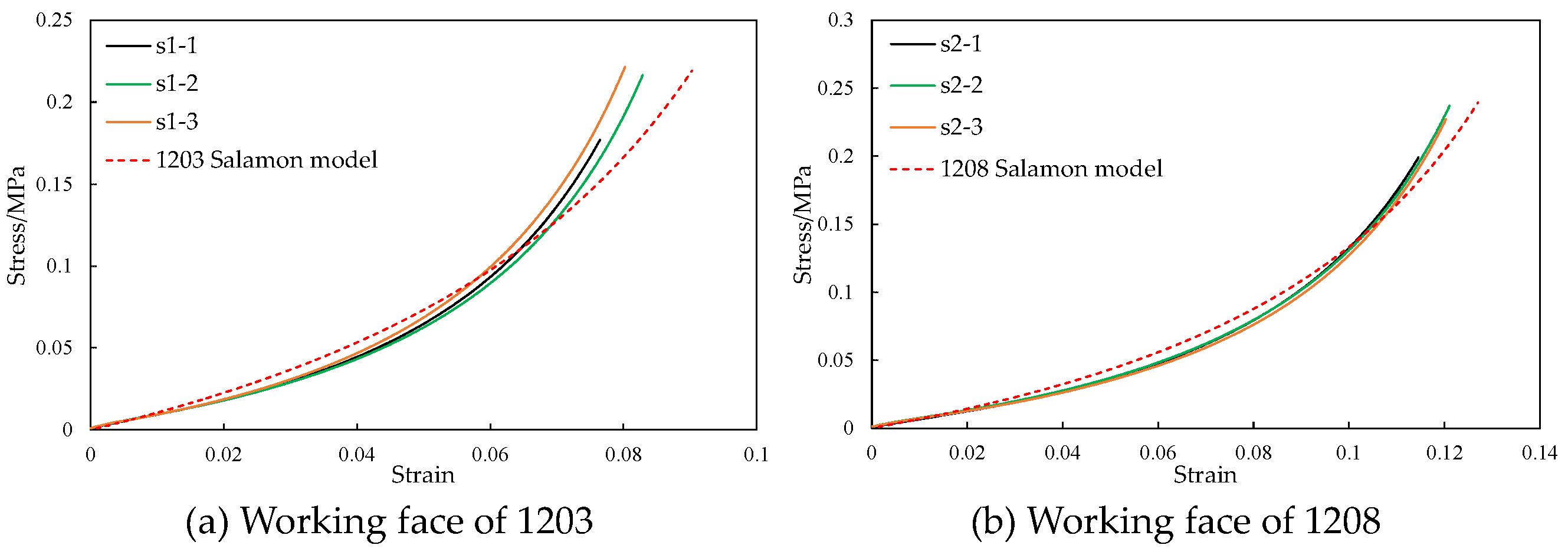

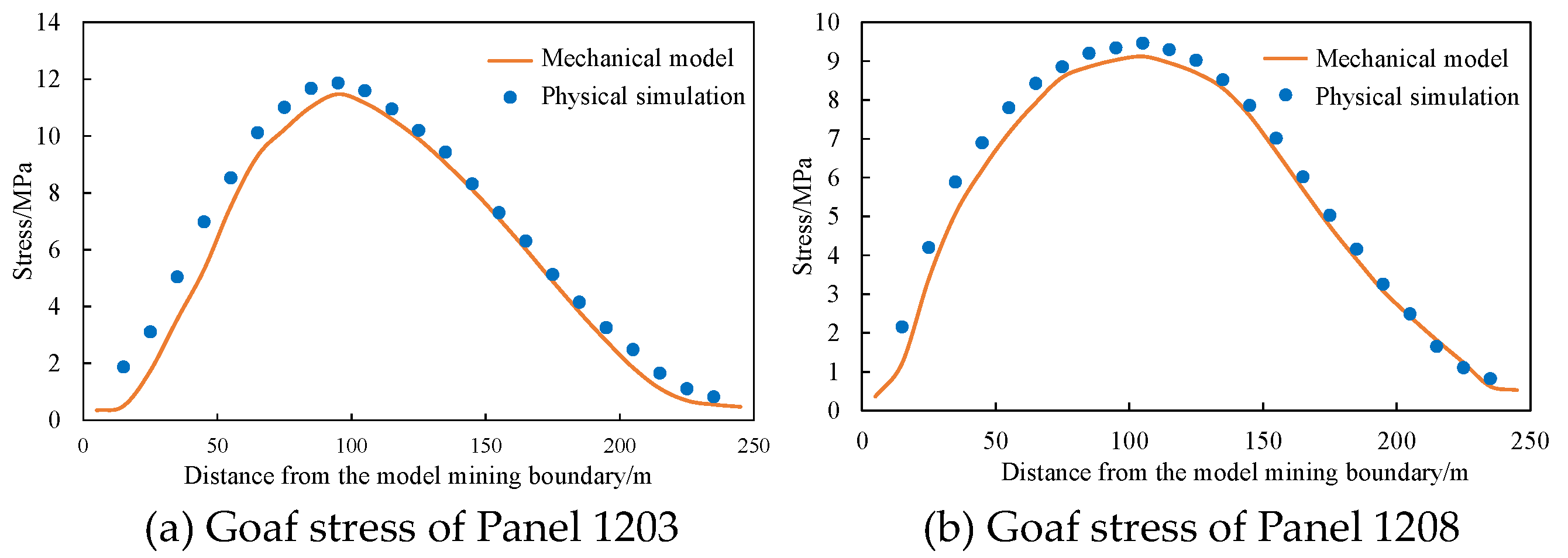

4.4. Validation of the New Similar Simulation Material

4.4.1. Verification of Caving Zone Compression

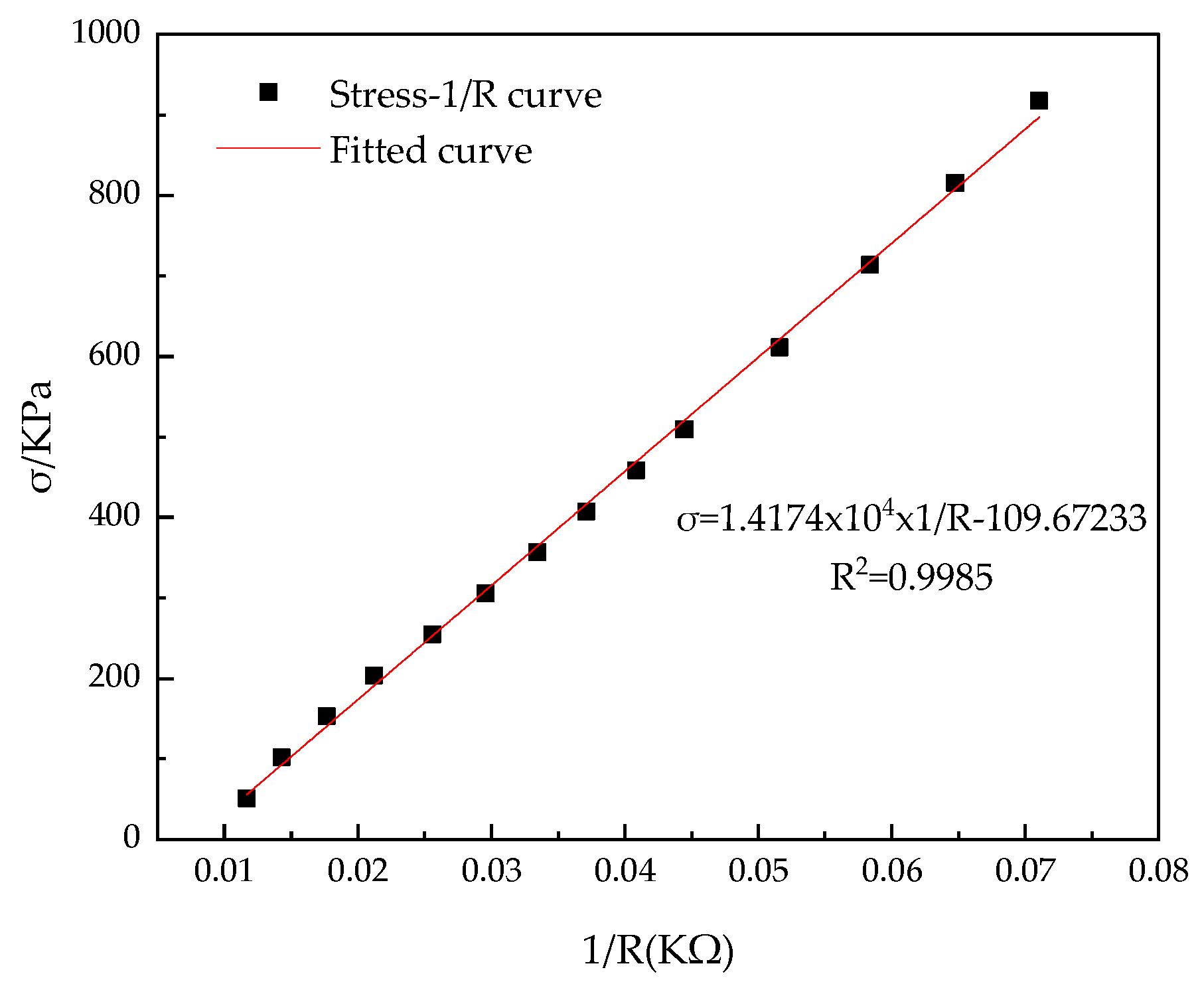

4.4.2. Feasibility Validation Based on Goaf Stress

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- A novel method for simulating the bulking–compaction characteristics of the caving zone is proposed, breaking through the technical bottleneck where traditional materials struggle to accurately reproduce the bulking–compaction process of fragmented rock masses in goafs. Experimental results indicate that the stress–strain curve of the new SSM exhibits high consistency with the Salamon model. This addresses, at the constitutive relationship level, the critical issue of distortion in simulating rock mass bulking–compaction behavior in traditional physical simulations.

- (2)

- The dominant controlling factors of the stress–strain behavior of the new SSM are revealed. The study finds that the material’s mechanical response is significantly correlated only with the thickness of the EPE component and is independent of its position. Under fixed position conditions, the stress–strain response exhibits a non-linearly enhancing characteristic with increasing EPE thickness, and this strengthening effect becomes progressively more pronounced. Conversely, under different position conditions, the stress–strain curves remain essentially consistent.

- (3)

- A selection method for the dimensions of the new SSM under different working conditions has been established. In the curve-fitting formula for the new SSM, the initial tangent modulus (E) gradually decreases with increasing material thickness, while the maximum strain (εm1) increases with thickness. Therefore, based on the required numerical ranges of the E and εm1 for the target working condition, the corresponding thickness of the new SSM can be selected, thereby achieving precise simulation and matching of its mechanical behavior.

- (4)

- The feasibility of the new SSM for the caving zone is validated through physical simulation experiments. Taking the Shilawusu Coal Mine as an example, the simulation errors for key parameters—including caving zone compression subsidence, goaf stress, and stress in the central section of the working face—using the new SSM are all controlled within 12%. This fully demonstrates the feasibility of this material in physical simulations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, J.; Qin, W.; Xuan, D. Accumulative effect of overburden strata expansion induced by stress relief. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Qin, W.; Chen, X. Influencing factors of accumulative effect of overburden strata expansion induced by stress relief. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, J. Mining Pressure and Strata Control; China University of Mining and Technology Press: Xuzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Can, E.; Mekik, C.; Kuscu, S. Subsidence occurring in mining regions and a case study of Zonguldak-Kozlu basin. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Li, L. Rock strata failure and subsidence characteristics under the mining of short distance thick coal seams: A case in west China. Int. J. Glob. Energy Issues 2021, 43, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Han, X.; Zhang, J. Compressive deformation and energy dissipation of crushed coal gangue. Powder Technol. 2016, 297, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Miao, X.; Ge, X. Testing study on compaction breakage of loose rock blocks. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S. Method for determination of mined-out roof expansion coefficient of self-formed roadway without pillar. Saf. Coal Mines 2020, 51, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Mao, X.; Hu, G. Research on broken expand and press solid characteristics of rocks and coals. J. Exp. Mech. 1997, 3, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Tu, S.; Zhao, Y. Compaction characteristics of the caving zone in a longwall goaf: A review. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xu, N.; Guo, Y. Physical simulation of the influence of the original rock strength on the compaction characteristics of caving rock in longwall goaf. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 220558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, H. An estimation method for cover pressure re-establishment distance and pressure distribution in the goaf of longwall coal mines. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palchik, V. Bulking factors and extents of caved zones in weathered overburden of shallow abandoned underground workings. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 79, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, M. Mechanism of caving in longwall coal mining. In Rock Mechanics Contribution and Challenges, Proceedings of the 31th US Symposium of Rock Mechanics, Golden, CO, USA, 18–20 June 1990; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, D.M.; Mark, C. Behavior of Simulated Longwall Gob Material; Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Tao, G.; Cao, Z. Study on failure characteristics of stope overlying rock considering strain hardening characteristics of caved rock mass. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Tang, C.; Liang, Z. Investigation on overburden strata collapse around coal face considering effect of broken expansion of rock. Rock Soil Mech. 2010, 31, 3537–3541. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie, T.; Eberhardt, E.; Pierce, M.E. Numerical modelling of rock mass bulking and geometric dilation using a bonded block modelling approach to assist in support design for deep mining pillars. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 156, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z. Strata Caving and Gob Evolution Characteristic in Longwall Mining. Shock Vib. 2022, 2022, 3235063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Song, T.; Gu, W. Research on the Distribution Characteristics of the Bulking Coefficient in the Strike Direction of the Longwall Goaf Filled with Slurry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhanov, D.; Zhienbayev, A.; Zharaspaev, M. Determining the parameters for the overlying stratum caving zones during repeated mining of pillars. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Nguyen, C.K.; Tran, M.T. Longwall mining-induced weighting mechanism and its interactions with shield support and coal wall. Min. Miner. Depos. 2025, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Physical simulation research on the dynamic bulking of mining-induced fractured rock mass. Coal Prep. Technol. 2006, S1, 69–72+19. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, K.; Zhou, M.; Tan, Z. Study on Laws of Rockmass Breaking Induced by Mining. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 1998, 3, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, K.; Zhang, D. The study on the character of strata subsidence during repeat mining. J. China Coal Soc. 1998, 5, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cao, H.; Jiang, Z. Influence of Gangue Compaction Process on Coal Pillar Supporting Pressure in Goaf. Saf. Coal Mines 2020, 51, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Deng, K.; Zhou, M. Research on variation law of bulking factor of mining-induced rock mass. Energy Technol. Manag. 1998, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, L.; Kan, Z.; Cao, A. Physical Similarity Principles of Coal–Rock Dynamics Simulation for Coal Burst. J. China Coal Soc. 2025, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Bai, J.; Wang, X. Development and performance study on low strength and high rockburst tendency similar simulation material of coal. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K. The Experimental System and Application of Slurry Flow Simulation of Isolated Grouting Filling for Overburden. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J. Experiment on size effect of coal and rock deformation characteristics in coalmine underground reservoir. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2021, 38, 810–818. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, L. Permeability Characteristics of Broken Coal and Rock Under Cyclic Loading and Unloading. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 28, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Tu, S. Influence mechanism of particle size on the compaction and breakage characteristics of broken coal mass in goaf. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 660–670. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P.; Fan, B.; Cheng, J. The whole-cycle dynamic evolution characteristics of overburden fracture and movement in extremely high mining longwall face in western mining area. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025, 10, 648–660. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, J. Mining-induced displacement deformation law in full-columnar overburden and its design guidance in gas extraction. Fuel 2024, 363, 130934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group Number | EPE Position | EPE Thickness/cm | Group Number | EPE Position | EPE Thickness/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1-1 | a | 1 | s3-3 | c | 3 |

| s1-2 | b | 1 | s4-1 | a | 4 |

| s1-3 | c | 1 | s4-2 | b | 4 |

| s2-1 | a | 2 | s4-3 | c | 4 |

| s2-2 | b | 2 | s5-1 | a | 5 |

| s2-3 | c | 2 | s5-2 | b | 5 |

| s3-1 | a | 3 | s5-3 | c | 5 |

| s3-2 | b | 3 |

| Number | Lithology | Thickness/cm | Density (kg/m3) | Sand/kg | CaCO3/kg | Gypsum/kg | Layer Thickness/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KS4 | 10.50 | 1800 | 88.60 | 8.85 | 20.70 | 10.50 |

| 2 | Soft rock | 75.00 | 1800 | 723.20 | 84.40 | 36.20 | 2.50 |

| 3 | KS3 | 12.50 | 1800 | 105.50 | 10.50 | 24.60 | 12.50 |

| 4 | Soft rock | 30.50 | 1800 | 294.10 | 34.30 | 14.70 | 2.03 |

| 5 | KS2 | 15.00 | 1800 | 126.60 | 12.70 | 29.50 | 15.00 |

| 6 | Soft rock | 4.50 | 1800 | 43.40 | 5.10 | 2.20 | 2.25 |

| 7 | KS1 | 7.00 | 1800 | 63.00 | 4.70 | 11.00 | 7.00 |

| 8 | Soft rock | 2.50 | 1800 | 24.10 | 2.80 | 1.20 | 2.50 |

| 9 | Coal | 2.50 | 1800 | 16.40 | 1.60 | 0.70 | 2.50 |

| Number | Lithology | Thickness/cm | Density (kg/m3) | Sand/kg | CaCO3/kg | Gypsum/kg | Layer Thickness/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KS4 | 11.50 | 1800 | 97.00 | 9.70 | 22.60 | 11.50 |

| 2 | Soft rock | 82.50 | 1800 | 795.50 | 92.80 | 39.80 | 2.38 |

| 3 | KS3 | 9.50 | 1800 | 85.50 | 6.40 | 15.00 | 9.50 |

| 4 | Soft rock | 22.50 | 1800 | 217.00 | 25.30 | 10.80 | 2.25 |

| 5 | KS2 | 13.00 | 1800 | 109.70 | 11.00 | 25.60 | 13.00 |

| 6 | Soft rock | 12.00 | 1800 | 115.70 | 13.50 | 5.80 | 2.00 |

| 7 | KS1 | 9.00 | 1800 | 81.00 | 6.10 | 14.20 | 9.00 |

| 8 | Coal | 5.00 | 1800 | 32.80 | 3.30 | 1.40 | 5.00 |

| Working Face | Measurement Value | Theoretical Value | Error | Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1203 | 1.57 | 1.73 | 0.16 | 10.19% |

| 1208 | 1.83 | 1.64 | −0.19 | −10.38% |

| Distance of Boundary | Measurement Value | Theoretical Value | Error | Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | 8.53 | 7.52 | −1.01 | −11.84% |

| 130 | 10.12 | 9.30 | −0.82 | −8.13% |

| 150 | 11.01 | 10.22 | −0.79 | −7.14% |

| 170 | 11.68 | 11.03 | −0.65 | −5.58% |

| 190 | 11.87 | 11.47 | −0.40 | −3.35% |

| 210 | 11.59 | 11.16 | −0.43 | −3.73% |

| 230 | 10.95 | 10.60 | −0.36 | −3.24% |

| 250 | 10.21 | 9.89 | −0.31 | −3.08% |

| 270 | 9.43 | 9.05 | −0.38 | −4.02% |

| 290 | 8.32 | 8.12 | −0.20 | −2.42% |

| 310 | 7.30 | 7.09 | −0.21 | −2.90% |

| 330 | 6.30 | 6.01 | −0.29 | −4.60% |

| 350 | 5.12 | 4.89 | −0.23 | −4.55% |

| 370 | 4.16 | 3.81 | −0.35 | −8.39% |

| Distance of Boundary | Measurement Value | Theoretical Value | Error | Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 6.90 | 6.21 | −0.69 | −10.06% |

| 110 | 7.80 | 7.16 | −0.64 | −8.23% |

| 130 | 8.43 | 7.94 | −0.49 | −5.81% |

| 150 | 8.85 | 8.59 | −0.27 | −3.02% |

| 170 | 9.20 | 8.86 | −0.34 | −3.75% |

| 190 | 9.35 | 9.03 | −0.32 | −3.39% |

| 210 | 9.46 | 9.12 | −0.34 | −3.60% |

| 230 | 9.30 | 8.96 | −0.34 | −3.69% |

| 250 | 9.02 | 8.70 | −0.32 | −3.56% |

| 270 | 8.52 | 8.30 | −0.22 | −2.54% |

| 290 | 7.86 | 7.59 | −0.27 | −3.43% |

| 310 | 7.01 | 6.67 | −0.34 | −4.91% |

| 330 | 6.02 | 5.70 | −0.32 | −5.35% |

| 350 | 5.03 | 4.74 | −0.28 | −5.63% |

| 370 | 4.16 | 3.90 | −0.26 | −6.26% |

| 390 | 3.26 | 3.08 | −0.17 | −5.36% |

| 410 | 2.49 | 2.42 | −0.06 | −2.58% |

| 430 | 1.65 | 1.81 | 0.16 | 9.59% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Qin, W.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Yao, R. A Physical Modeling Method for the Bulking–Compaction Behavior of Rock Mass in the Caving Zone. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010423

Chen X, Qin W, Xu J, Li J, Yao R. A Physical Modeling Method for the Bulking–Compaction Behavior of Rock Mass in the Caving Zone. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010423

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiaojun, Wei Qin, Jialin Xu, Jian Li, and Ruilin Yao. 2026. "A Physical Modeling Method for the Bulking–Compaction Behavior of Rock Mass in the Caving Zone" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010423

APA StyleChen, X., Qin, W., Xu, J., Li, J., & Yao, R. (2026). A Physical Modeling Method for the Bulking–Compaction Behavior of Rock Mass in the Caving Zone. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010423