Signal in the Noise: Dispersion as a Marker of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Protocol

2.3. Sociodemographic and Stroke-Related Characteristics

2.4. Physical Disability and Strength

2.5. Neuropsychological Battery

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Physical Disability and Strength

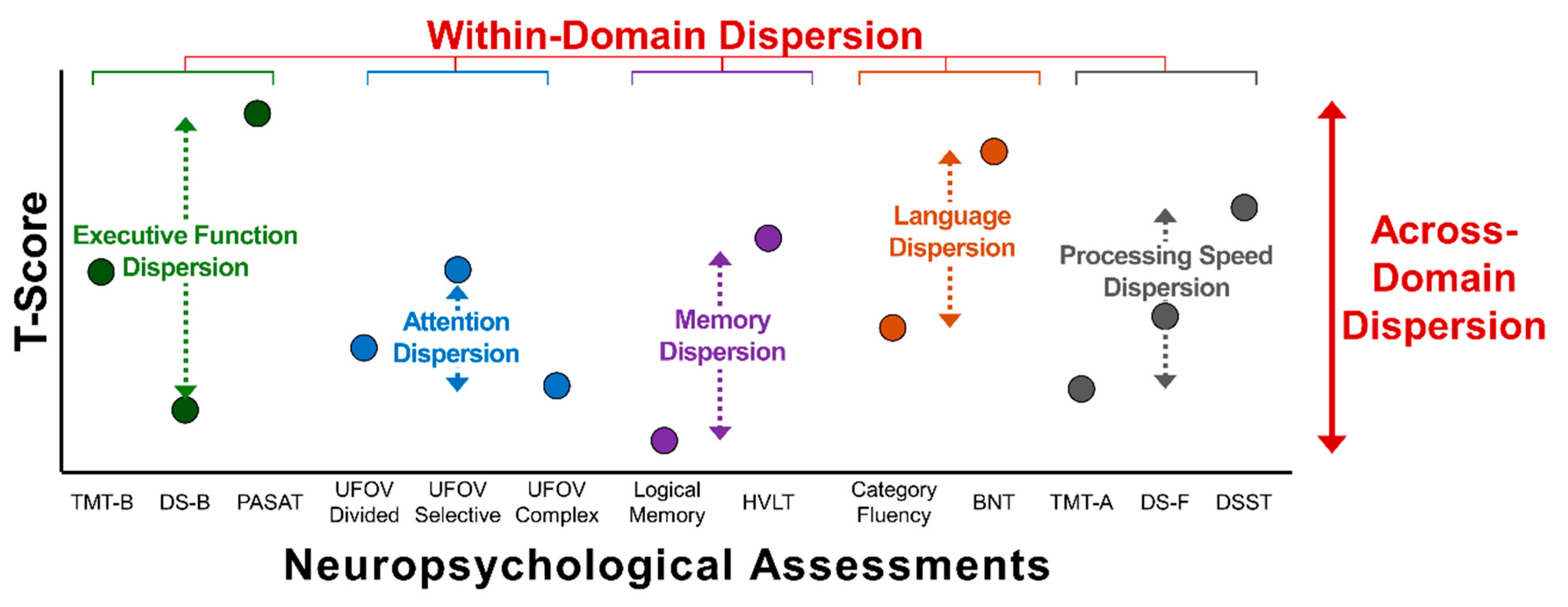

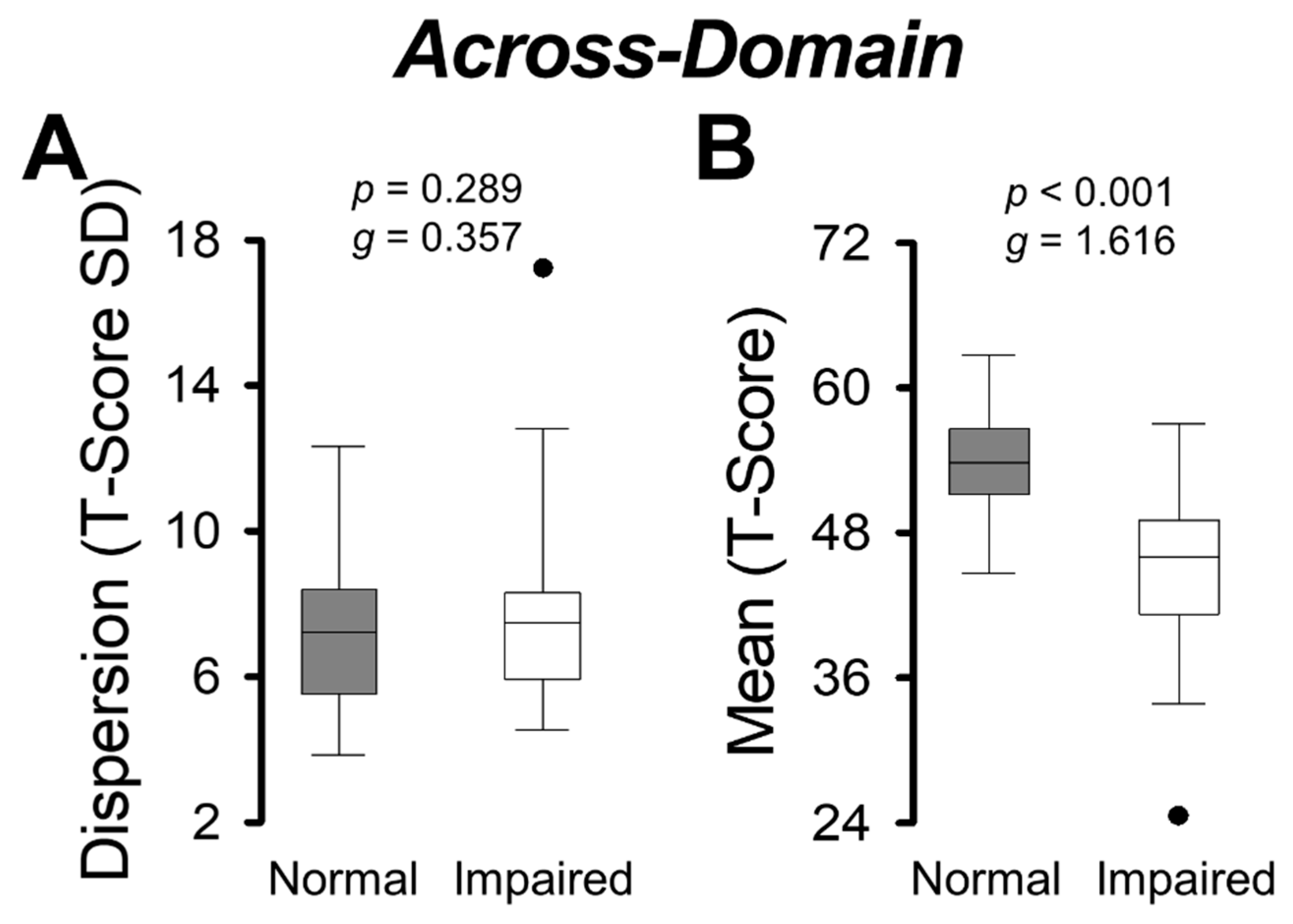

3.3. Group Comparisons on Across-Domain Dispersion and Mean

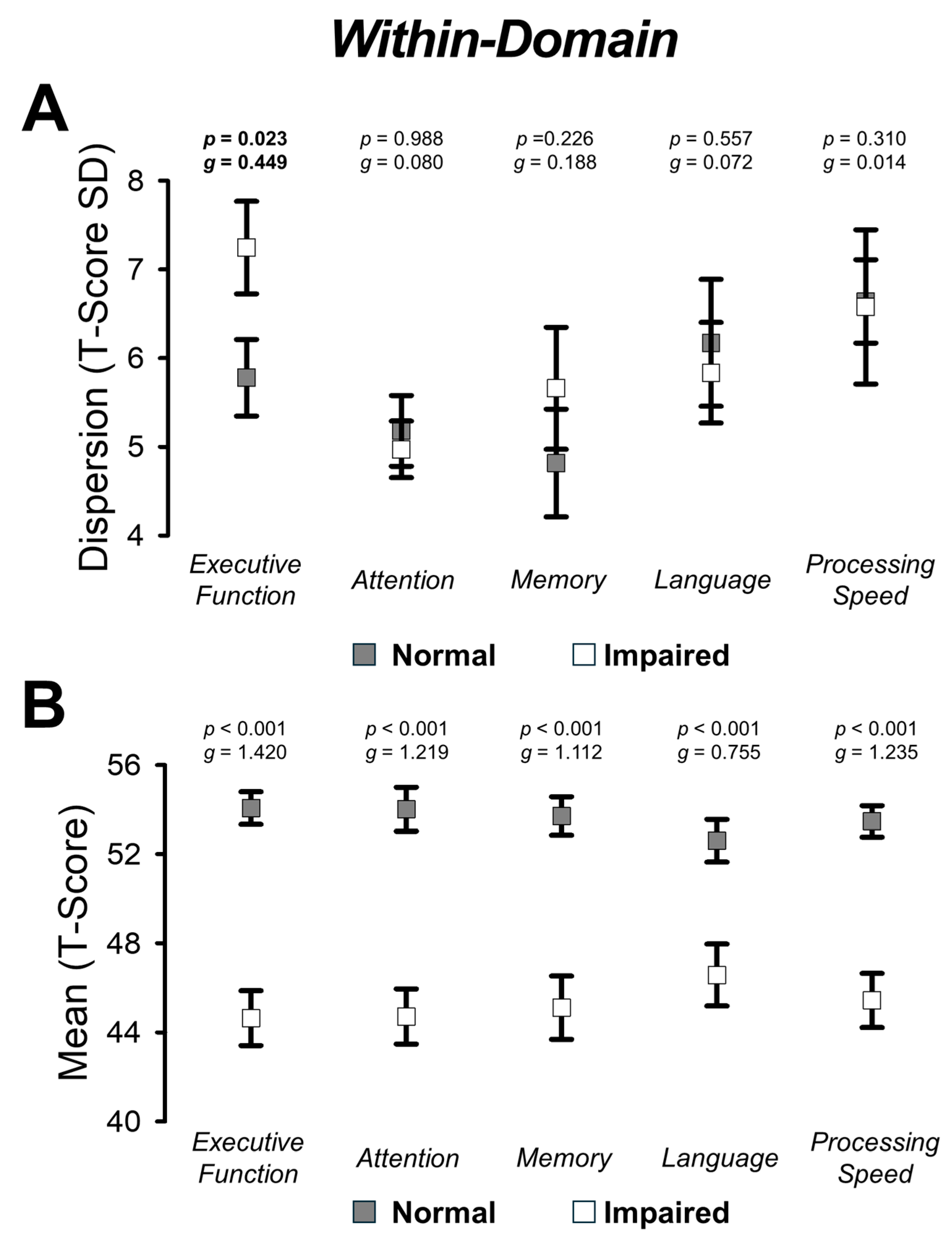

3.4. Group Comparisons on Within-Domain Dispersion and Mean

4. Discussion

4.1. Variability in Executive Functioning Is Exacerbated in Individuals with Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

4.2. Variability Across Cognitive Domains Is Similar Among Stroke Individuals

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Further Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BNT | Boston Naming Test |

| CSU | Colorado State University |

| DRS-2 AEMSS | Dementia Rating Scale (age- and education-adjusted) |

| DS-B | Digit Span-Backwards |

| DS-F | Digit Span-Forwards |

| DSST | Digit Symbol Substitution Test |

| HVLT | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| NINDS-CSN | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network |

| PASAT | Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test |

| TMT-A | Trail Making Test-Part A |

| TMT-B | Trail Making Test Part B |

| UFOV | Useful Field of View |

References

- El Husseini, N.; Katzan, I.L.; Rost, N.S.; Blake, M.L.; Byun, E.; Pendlebury, S.T.; Aparicio, H.J.; Marquine, M.J.; Gottesman, R.F.; Smith, E.E. Cognitive Impairment After Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2023, 54, E272–E291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendlebury, S.T.; Rothwell, P.M. Incidence and Prevalence of Dementia Associated with Transient Ischaemic Attack and Stroke: Analysis of the Population-Based Oxford Vascular Study. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, E.; McLoughlin, A.; Williams, D.J.; Merriman, N.A.; Donnelly, N.; Rohde, D.; Hickey, A.; Wren, M.A.; Bennett, K. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment No Dementia in the First Year Post-Stroke. Eur. Stroke J. 2019, 4, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douiri, A.; Rudd, A.G.; Wolfe, C.D.A. Prevalence of Poststroke Cognitive Impairment: South London Stroke Register 1995–2010. Stroke 2013, 44, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, E93–E621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbay, M.; Diouf, M.; Roussel, M.; Godefroy, O. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence in Post-Stroke Neurocognitive Disorders in Hospital-Based Studies. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2019, 46, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijajlović, M.D.; Pavlović, A.; Brainin, M.; Heiss, W.D.; Quinn, T.J.; Ihle-Hansen, H.B.; Hermann, D.M.; Assayag, E.B.; Richard, E.; Thiel, A.; et al. Post-Stroke Dementia—A Comprehensive Review. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks: A Compass for Global Action. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2980–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.H.; Kang, S.H.; Seo, K.M.; Kim, D.K.; Shin, H.I.; Shin, H.E. Relationship Between Grip and Pinch Strength and Activities of Daily Living in Stroke Patients. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 39, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövdén, M.; Li, S.-C.; Shing, Y.L.; Lindenberger, U. Within-Person Trial-to-Trial Variability Precedes and Predicts Cognitive Decline in Old and Very Old Age: Longitudinal Data from the Berlin Aging Study. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 2827–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzer, R.; Mahoney, J.; Verghese, J. Intraindividual Variability in Executive Functions but Not Speed of Processing or Conflict Resolution Predicts Performance Differences in Gait Speed in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 69, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultsch, D.F.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Dixon, R.A. Variability in Reaction Time Performance of Younger and Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2002, 57, P101–P115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.D.; Balota, D.A.; Duchek, J.M.; Head, D. White Matter Integrity and Reaction Time Intraindividual Variability in Healthy Aging and Early-Stage Alzheimer Disease. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, S.W.S.; Nyberg, L.; Bäckman, L. Intra-Individual Variability in Behavior: Links to Brain Structure, Neurotransmission and Neuronal Activity. Trends Neurosci. 2006, 29, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjell, A.M.; Westlye, L.T.; Amlien, I.K.; Walhovd, K.B. Reduced White Matter Integrity Is Related to Cognitive Instability. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 18060–18072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuss, D.T.; Pogue, J.; Buckle, L.; Bondar, J. Characterization of Stability of Performance in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: Variability and Consistency on Reaction Time Tests. Neuropsychology 1994, 8, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.L.; Hultsch, D.F.; Strauss, E.; Hunter, M.A. Intraindividual Variability in Physical and Emotional Functioning: Comparison of Adults with Traumatic Brain Injuries and Healthy Adults. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2002, 16, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.L.; Strauss, E.; Hultsch, D.F.; Moll, A.; Hunter, M.A. Intraindividual Variability as a Marker of Neurological Dysfunction: A Comparison of Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2006, 28, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, D.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Hultsch, D.F. Inconsistency in Serial Choice Decision and Motor Reaction Times Dissociate in Younger and Older Adults. Brain Cogn. 2004, 56, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultsch, D.F.; MacDonald, S.W.S. Intraindividual Variability in Performance as a Theoretical Window onto Cognitive Aging. In New Frontiers in Cognitive Aging, 1st ed.; Dixon, R., Backman, L., Nilsson, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch, D.F.; Strauss, E.; Hunter, M.A.; MacDonald, S.W.S. Intraindividual Variability, Cognition, and Aging. In The Handbook of Aging and Cognition, 3rd ed.; Craik, F.I.M., Salthouse, T.A., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 491–556. [Google Scholar]

- Kälin, A.M.; Pflüger, M.; Gietl, A.F.; Riese, F.; Jäncke, L.; Nitsch, R.M.; Hock, C. Intraindividual Variability across Cognitive Tasks as a Potential Marker for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 89204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, R.P.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. Between-Domain Cognitive Dispersion and Functional Abilities in Older Adults. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2015, 37, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, N.S.; Hill, B.D.; Duff, K.; Mold, J.; Scott, J.G. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) Intraindividual Variability in Older Adults: Associations with Disease and Mortality. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2015, 37, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangen, K.J.; Weigand, A.J.; Thomas, K.R.; Delano-Wood, L.; Clark, L.R.; Eppig, J.; Werhane, M.L.; Edmonds, E.C.; Bondi, M.W. Cognitive Dispersion Is a Sensitive Marker for Early Neurodegenerative Changes and Functional Decline in Nondemented Older Adults. Neuropsychology 2019, 33, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E.; Del Bene, V.A.; Frank, J.S.; Billings, R.; Triebel, K.; Buchholz, A.; Rubin, L.H.; Woods, S.P.; Li, W.; Fazeli, P.L. Cognitive Intra-Individual Variability in HIV: An Integrative Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2022, 32, 855–876. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, K.S.; O’Connell, M.E.; Kirk, A.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Morgan, D. Intraindividual Variability Measured with Dispersion across Diagnostic Groups in a Memory Clinic Sample. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2023, 30, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mulet-Pons, L.; Solé-Padullés, C.; Cabello-Toscano, M.; Abellaneda-Pérez, K.; Perellón-Alfonso, R.; Cattaneo, G.; Sánchez, J.S.; Alviarez-Schulze, V.; Bargalló, N.; Tormos-Muñoz, J.M.; et al. Brain Connectivity Correlates of Cognitive Dispersion in a Healthy Middle-Aged Population: Influence of Subjective Cognitive Complaints. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2023, 78, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, B.M.; Austin, T.; Royall, D.R.; Hilsabeck, R.C. Cognitive Intraindividual Variability as a Potential Biomarker for Early Detection of Cognitive and Functional Decline. Neuropsychology 2022, 37, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- DesRuisseaux, L.A.; Guevara, J.E.; Duff, K. Examining the Stability and Predictive Utility of Across- and Within-Domain Intra-Individual Variability in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2025, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuss, D.T.; Murphy, K.J.; Binns, M.A.; Alexander, M.P. Staying on the Job: The Frontal Lobes Control Individual Performance Variability. Brain 2003, 126, 2363–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Mackinnon, A.J.; Korten, A.E.; Jorm, A.F.; Henderson, A.S.; Jacomb, P. Dispersion in Cognitive Ability as a Function of Age: A Longitudinal Study of an Elderly Community Sample. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 1999, 6, 214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, D.W.R.; Stawski, R.S.; Cerino, E.S.; Decarlo, C.A.; Grewal, K.; Macdonald, S.W.S. Intraindividual Variability across Neuropsychological Tests: Dispersion and Disengaged Lifestyle Increase Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Intell. 2018, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tractenberg, R.E.; Pietrzak, R.H. Intra-Individual Variability in Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Aging: Definitions, Context, and Effect Sizes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16973. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, M.A.; Schnaider-Beeri, M.; Sano, M.; Silverman, J.M.; Haroutunian, V. Cross-Domain Variability of Cognitive Performance in Very Old Nursing Home Residents and Community Dwellers: Relationship to Functional Status. Gerontology 2005, 51, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachinski, V.; Iadecola, C.; Petersen, R.C.; Breteler, M.M.; Nyenhuis, D.L.; Black, S.E.; Powers, W.J.; DeCarli, C.; Merino, J.G.; Kalaria, R.N.; et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Canadian Stroke Network Vascular Cognitive Impairment Harmonization Standards. Stroke 2006, 37, 2220–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, G.; Pantoni, L. Use of Montreal Cognitive Assessment in Patients with Stroke. Stroke 2014, 45, 3135–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springate, B.A.; Tremont, G.; Papandonatos, G.; Ott, B.R. Screening for Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Dementia Rating Scale-2. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2014, 27, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saver, J.L.; Chaisinanunkul, N.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Grotta, J.C.; Hill, M.D.; Khatri, P.; Landen, J.; Lansberg, M.G.; Venkatasubramanian, C.; Albers, G.W. Standardized Nomenclature for Modified Rankin Scale Global Disability Outcomes: Consensus Recommendations from Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable XI. Stroke 2021, 52, 3054–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ada, D.L.; O’Dwyer, N.; Ada, D.L.; O’Dwyer, N.; O’Neill, E. Relation between Spasticity, Weakness and Contracture of the Elbow Flexors and Upper Limb Activity after Stroke: An Observational Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.K.; McArthur, K.S.; Quinn, T.J. Assessment Scales in Stroke: Clinimetric and Clinical Considerations. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canning, C.G.; Ada, L.; Adams, R.; O’Dwyer, N.J. Loss of Strength Contributes More to Physical Disability after Stroke than Loss of Dexterity. Clin. Rehabil. 2004, 18, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Fortini, I.; Michaelsen, S.M.; Cassiano, J.G.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F. Upper Extremity Function in Stroke Subjects: Relationships between the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Domains. J. Hand Ther. 2011, 24, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Fortini, I.; Basílio, M.L.; Polese, J.C.; Menezes, K.K.P.; Faria, C.D.C.M.; Scianni, A.A.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F. Strength Deficits of the Paretic Lower Extremity Muscles Were the Impairment Variables That Best Explained Restrictions in Participation after Stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 2158–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissy, P.; Bourbonnais, D.; Carlotti, M.M.; Gravel, D.; Arsenault, B.A. Maximal Grip Force in Chronic Stroke Subjects and Its Relationship to Global Upper Extremity Function. Clin. Rehabil. 1999, 13, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R.; Thrane, G.; Askim, T.; Anke, A.; Mork, P.J. Development of Grip Strength during the First Year after Stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazer, B.L.; Sofer, S.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Gelinas, I. Use of the UFOV to Evaluate and Retrain Visual Attention Skills in Clients with Stroke: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2001, 55, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitan, R.M. Trail Making Test: Manual for Administration and Scoring; Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, C.R.; Harvey, P.D. Administration and Interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2277–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.L.; Kishiyama, M.M.; Yund, E.W.; Herron, T.J.; Edwards, B.; Poliva, O.; Hink, R.F.; Reed, B. Improving Digit Span Assessment of Short-Term Verbal Memory. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2011, 33, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, J. Digit Symbol Substitution Test. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 38, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.D.; Yi, D.; Joung, H.; Seo, E.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Byun, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Jeon, S.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Sohn, B.K.; et al. Normative Data for the Logical Memory Subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-IV in Middle-Aged and Elderly Korean People. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkonen, S. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology, 2nd ed.; Kreutzer, J.S., DeLuca, J., Caplan, B., Eds.; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1733–1735. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, J.A.; Ivnik, R.J.; Smith, G.E.; Bohac, D.L.; Tangalos, E.G.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Petersen, R.C. Mayo’s Older Americans Normative Studies: Category Fluency Norms. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998, 20, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.F.; Goodglass, H.; Weintraub, S. The Boston Naming Test, 2nd ed.; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh, T.N. A Comprehensive Review of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT). Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 21, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.H.; Linn, R.T.; Szymanski, H.; Coad, M.L.; Wack, D.S. Mapping the Neural Systems That Mediate the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT). J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, K.S.; Wilson, S.M.; Giesser, B.S.; Drain, A.E.; Sicotte, N.L. A Longitudinal FMRI Study of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E.; Azuero, A.; Vinikoor, M.; Schexnayder, J.K.; Puga, F.; Galatzan, B.; Byun, J.Y.; Xiao, C.; Phaowiriya, H.; James, D.L.; et al. Cognitive Intra-Individual Variability as an Outcome or Moderator of Speed of Processing Training in Aging Adults with HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder: A Secondary Data Analysis of a 2-Year Longitudinal Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. Plus 2024, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herve, A. Coefficient of Variation. Encycl. Res. Des. 2010, 1, 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H.; Dear, K.B.G.; Anstey, K.J.; Parslow, R.A.; Sachdev, P.; Jorm, A.F. Within-Occasion Intraindividual Variability and Preclinical Diagnostic Status: Is Intraindividual Variability an Indicator of Mild Cognitive Impairment? Neuropsychology 2005, 19, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjasvaara, T.; Leskelä, M.; Vataja, R.; Kalska, H.; Ylikoski, R.; Hietanen, M.; Leppävuori, A.; Kaste, M.; Erkinjuntti, T. Post-Stroke Depression, Executive Dysfunction and Functional Outcome. Eur. J. Neurol. 2002, 9, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasquin, S.M.C.; Lodder, J.; Ponds, R.W.H.M.; Winkens, I.; Jolles, J.; Verhey, F.R.J. Cognitive Functioning after Stroke: A One-Year Follow-up Study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2004, 18, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilborn, J.V.; Strauss, E.; Hultsch, D.F.; Hunter, M.A. Intraindividual Variability across Cognitive Domains: Investigation of Dispersion Levels and Performance Profiles in Older Adults. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2009, 31, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, H.; Melkas, S.; Ylikoski, R.; Pohjasvaara, T.; Kaste, M.; Erkinjuntti, T.; Hietanen, M. Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment Is Common Even after Successful Clinical Recovery. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hornby, T.G.; Henderson, C.E.; Plawecki, A.; Lucas, E.; Lotter, J.; Holthus, M.; Brazg, G.; Fahey, M.; Woodward, J.; Ardestani, M.; et al. Contributions of Stepping Intensity and Variability to Mobility in Individuals Poststroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Felice, S.; Holland, C.A. Intra-Individual Variability across Fluid Cognition Can Reveal Qualitatively Different Cognitive Styles of the Aging Brain. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 390642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzer, R.; Verghese, J.; Wang, C.; Hall, C.B.; Lipton, R.B. Within-Person Across-Neuropsychological Test Variability and Incident Dementia. JAMA 2008, 300, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Kuhn, T.; Mahmood, Z.; Singer, E.J.; Hinkin, C.H.; Thames, A.D. Longitudinal Intra-Individual Variability in Neuropsychological Performance Relates to White Matter Changes in HIV. Neuropsychology 2018, 32, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koscik, R.L.; Berman, S.E.; Clark, L.R.; Mueller, K.D.; Okonkwo, O.C.; Gleason, C.E.; Hermann, B.P.; Sager, M.A.; Johnson, S.C. Intraindividual Cognitive Variability in Middle Age Predicts Cognitive Impairment 8–10 Years Later: Results from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2016, 22, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Cognitively Normal | Cognitively Impaired | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 54 | 41 | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 62.47 ± 13.97 | 70.53 ± 10.38 | 0.002 |

| Years of education, mean ± SD | 16.42 ± 2.38 | 15.13 ± 2.40 | 0.007 |

| Women, % | 44.44 | 48.78 | 0.675 |

| Ethnicity, % | 0.134 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 98.15 | 87.80 | |

| African American | 0 | 7.32 | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 2.44 | |

| Other | 1.85 | 2.44 | |

| Side Dominance, % | 0.713 | ||

| Right | 85.19 | 87.80 | |

| Left | 14.81 | 12.20 | |

| Type of stroke, % | 0.086 | ||

| Ischemic | 85.19 | 70.73 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 3.70 | 14.63 | |

| Both | 0 | 4.88 | |

| Unknown | 11.11 | 9.76 | |

| Side of the lesion, % | 0.335 | ||

| Right | 35.19 | 26.83 | |

| Left | 46.30 | 39.02 | |

| Both | 7.40 | 9.76 | |

| Unknown | 11.11 | 24.39 | |

| Lesion location, % | 0.333 | ||

| Infratentorial | 12.96 | 12.20 | |

| Supratentorial | 64.81 | 48.78 | |

| Both | 5.56 | 12.20 | |

| Unknown | 16.67 | 26.83 | |

| Affected Side, % | 0.341 | ||

| Right | 38.89 | 43.90 | |

| Left | 37.04 | 43.90 | |

| Other | 24.07 | 12.20 | |

| Years since stroke, mean ± SD | 4.56 ± 6.81 | 4.51 ± 6.67 | 0.976 |

| modified Rankin Score | 0.378 | ||

| 0, % | 24.07 | 9.76 | |

| 1, % | 44.44 | 46.34 | |

| 2, % | 25.93 | 31.71 | |

| 3, % | 3.70 | 7.32 | |

| 4, % | 1.85 | 4.88 |

| Variable | Cognitively Normal | Cognitively Impaired |

|---|---|---|

| Across-Domain | ||

| Dispersion | 7.08 ± 1.95 | 7.87 ± 2.48 |

| Mean | 53.64 ± 4.27 | 45.21 ± 6.18 |

| Within-Domain | ||

| Executive Function | ||

| Dispersion | 5.77 ± 3.17 | 7.25 ± 3.34 |

| Mean | 54.07 ± 5.38 | 44.64 ± 7.91 |

| Attention | ||

| Dispersion | 5.18 ± 2.93 | 4.97 ± 2.04 |

| Mean | 54.02 ± 7.28 | 44.71 ± 7.94 |

| Memory | ||

| Dispersion | 4.82 ± 4.46 | 5.66 ± 4.40 |

| Mean | 53.71 ± 6.37 | 45.11 ± 9.12 |

| Language | ||

| Dispersion | 6.17 ± 5.26 | 5.84 ± 3.63 |

| Mean | 52.60 ± 7.07 | 46.57 ± 8.92 |

| Processing Speed | ||

| Dispersion | 6.64 ± 3.45 | 6.58 ± 5.57 |

| Mean | 53.47 ± 5.21 | 45.43 ± 7.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Delmas, S.; Tiwari, A.; Lodha, N. Signal in the Noise: Dispersion as a Marker of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010388

Delmas S, Tiwari A, Lodha N. Signal in the Noise: Dispersion as a Marker of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010388

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelmas, Stefan, Anjali Tiwari, and Neha Lodha. 2026. "Signal in the Noise: Dispersion as a Marker of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010388

APA StyleDelmas, S., Tiwari, A., & Lodha, N. (2026). Signal in the Noise: Dispersion as a Marker of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010388