1. Introduction

In the field of space robotics, flexible manipulators have garnered significant attention due to their distinctive advantages. Compared to traditional industrial manipulators, which are characterized by high rigidity, high energy consumption, and relatively low precision, flexible manipulators feature lightweight long-link structures, low moment of inertia, and high transmission efficiency [

1]. These attributes make them well-suited for applications in space exploration. A spatial flexible manipulator constitutes a complex high-order, strongly coupled, nonlinear, and time-varying system. It faces challenges such as vibrations induced by structural flexibility, model uncertainties, parameter variations, and external disturbances. If not properly controlled, these issues may degrade system performance and stability.

In the work by Shang D et al. [

2], the dual-flexibility coupling and two-dimensional deformation characteristics of the system are explored. This paper employs the assumed mode method to describe the transverse and longitudinal deformations of the flexible load and establishes a dynamic model using Lagrange’s theorem. Furthermore, the vibration mechanism of the flexible manipulator is explained from an energy perspective, providing valuable insights for system modeling in this field.

Numerous control strategies have been developed to address system uncertainties and parameter variations in the control of spatial flexible manipulators. These include fuzzy algorithms [

3], PID control [

4], reinforcement learning [

5], singular perturbation methods [

6], and sliding mode control [

7]. As an important branch of variable structure control, SMC is well-known for its insensitivity to system uncertainties and parameter variations [

8]. Consequently, it has been widely applied in satellite systems [

9], robotic manipulators [

10], and other fields. However, conventional SMC suffers from issues such as slow response, singularities, and chattering in the control input [

11]. To overcome these limitations, a non-singular terminal sliding mode (NTSM) approach was designed in and applied to multi-joint manipulator systems, enabling stable and rapid convergence to the equilibrium point. Despite this improvement, NTSM still exhibits chattering, which degrades system performance. To suppress chattering, Reference [

12] replaced the sign function with a hyperbolic tangent function, while Van M et al. [

13] designed the sliding surface using a saturation function. In contrast, Zhang J et al. [

14] employed a higher-order sliding mode (HOSM) to design the control law. By increasing the sliding order to hide discontinuities, this approach effectively reduces chattering while maintaining the strong robustness of first-order SMC. Nevertheless, it sacrifices robustness within the boundary layer of the switching function to achieve smoothness. To address these trade-offs, a super-twisting algorithm sliding mode control was proposed in [

15]. This method preserves the advantages of HOSM and introduces an integral term to compensate for disturbances and smooth the output. Its structure inherently avoids high-frequency switching, thereby significantly mitigating chattering.

On the other hand, the motion of flexible joints is significantly affected by nonlinear friction torque [

16]. Therefore, nonlinear friction models must be considered when establishing the dynamic equations of spatial flexible manipulator systems. Additionally, as the system itself contains numerous nonlinearities, researchers often treat external disturbances (such as nonlinear friction) and other nonlinear terms as system uncertainties [

17]. Substantial uncertainties in the model can induce chattering. This phenomenon can cause severe damage to actuators and mechanical components, making adequate compensation for model uncertainties particularly necessary. For instance, Reference [

18] employed a disturbance observer to asymptotically estimate unmodeled external disturbances and compensate for their effects. Consequently, the integration of disturbance observers with sliding mode control to suppress chattering from the perspective of external disturbances has become a research focus in the SMC field [

19]. With advancements in intelligent control, neural network techniques have also been widely adopted in robotics control. The Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural network, leveraging its universal approximation capability, can accurately approximate nonlinear dynamic parameters through an online learning mechanism [

20]. In Reference [

21], an RBF neural network was utilized to identify and compensate for uncertainties in a flexible manipulator system. By designing adaptive and control laws, the adverse effects of friction torque and nonlinearities were effectively mitigated.

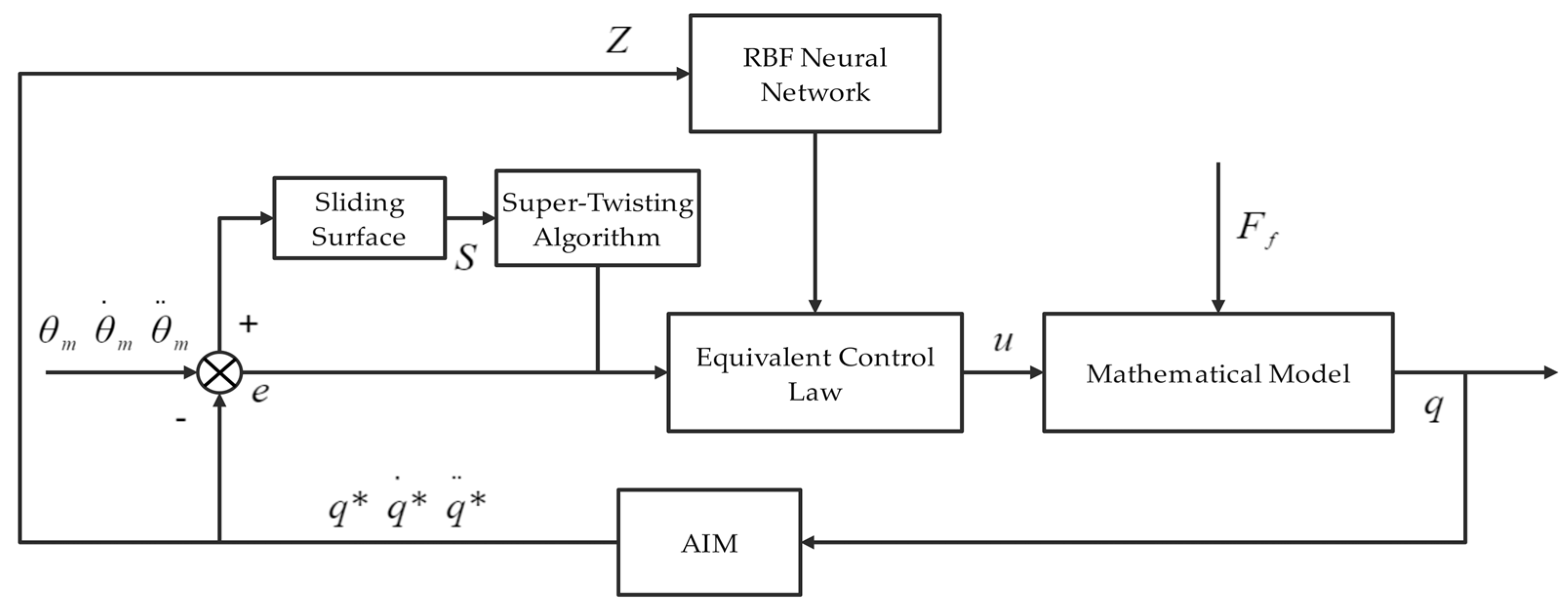

To address the aforementioned challenges in spatial flexible manipulators, we develop the system dynamics using Lagrange’s theorem and the assumed mode method. A super-twisting algorithm sliding mode control strategy, enhanced by a Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural network, is designed to compensate for system uncertainties. This integrated approach mitigates chattering induced by unmodeled dynamics and other uncertainties from multiple perspectives. The effectiveness of the proposed control strategy is validated through simulation experiments.

Regarding dynamic modeling, this work adopts the established Lagrangian method and assumed mode approach. This model accurately describes the dynamics of a dual-flexible servo system incorporating two-dimensional deformation, friction, and time-varying length, and its validity for precise representation has been previously verified. The primary contribution of this work lies in the control strategy. We propose a distinct improvement to address the chattering issue inherent in conventional sliding mode control (SMC) for flexible manipulators. While existing methods often mitigate chattering by modifying the switching function or introducing a boundary layer, our approach diverges by employing higher-order sliding mode (HOSM) concepts [

14]. Specifically, the super-twisting algorithm (STA)—an HOSM method—is applied to the flexible manipulator servo system. The super-twisting algorithm sliding mode control (STASMC) inherently suppresses chattering structurally while maintaining robustness against parameter variations and uncertainties. Furthermore, this is coupled with an RBF neural network that provides the real-time approximation of the system’s nonlinear and time-varying components. Together, they form a dual-enhancement mechanism characterized by “high-order chattering suppression + uncertainty compensation”. The proposed method theoretically guarantees finite-time convergence and enhanced stability, with its effectiveness being validated through simulation experiments.

2. Problem Representation and Dynamic Model Establishment

Throughout this paper, the terms “flexible manipulator” and “flexible load” refer to distinct but related concepts within the studied servo system. The flexible manipulator denotes the entire mechanical structure, which comprises a servo motor, a flexible joint, and a driven link that exhibits significant compliance. The flexible load specifically refers to that compliant driven link (modeled as a Euler–Bernoulli beam model) which is connected to the motor via the flexible joint and undergoes two-dimensional deformation during operation. Thus, the flexible load is a key component of the flexible manipulator system, and its dynamics are the primary focus of the modeling and control design presented in this work.

In view of the research status in the field of space robot, its mainstream control strategy focuses on joint control and whole arm control based on a dynamic model [

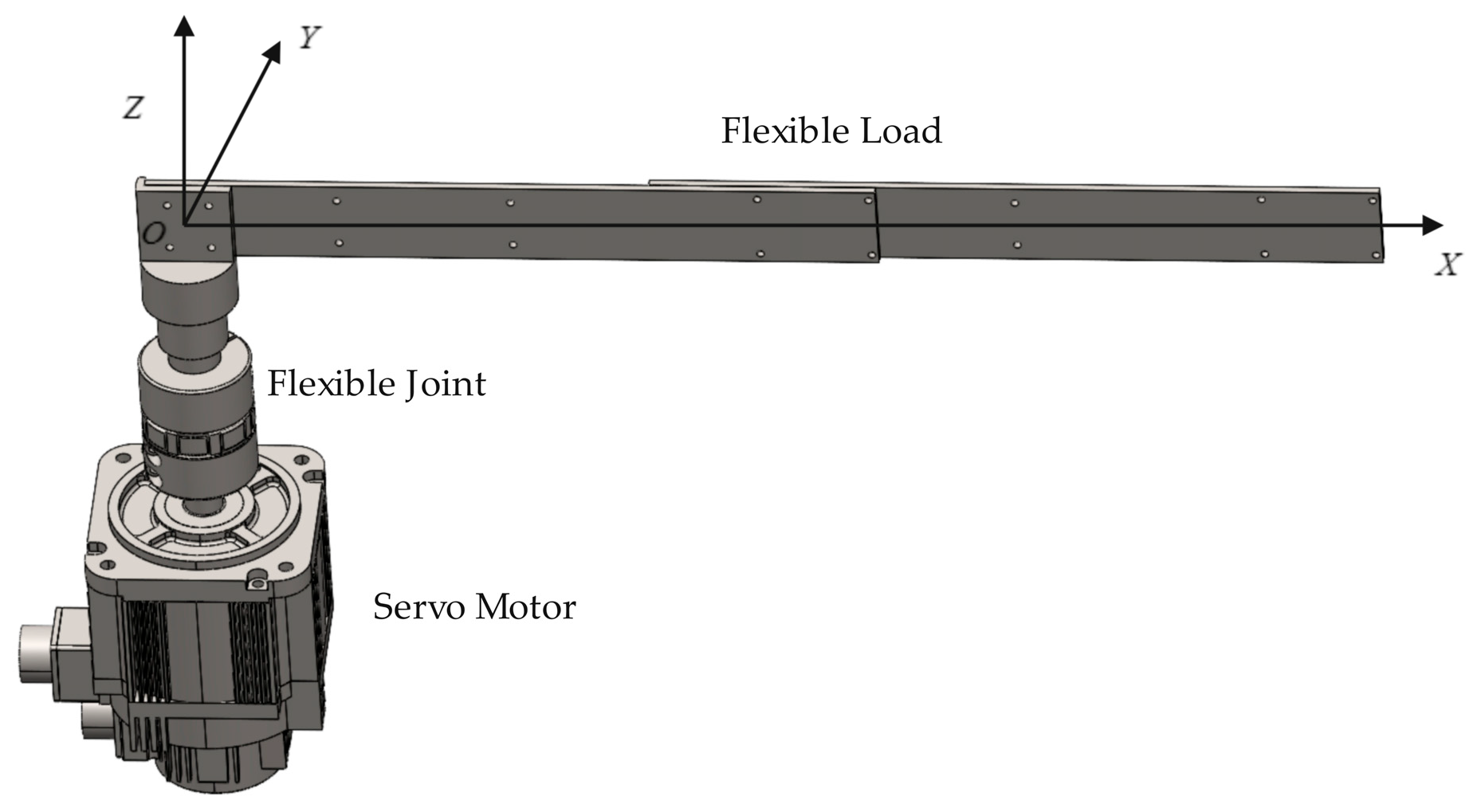

22]. For the convenience of assumption and research, we model the entire system as a single-link manipulator, actuated by a motor through flexible joints, as shown in

Figure 1. In line with many established studies in this field, this work simplifies the spatial flexible manipulator system to a planar single-link model for investigation. The core dynamic challenge of the spatial manipulator—namely, the coupling between vibrations induced by flexible deformation and the rotational motion—is fully preserved in this simplified model. Secondary factors, such as three-dimensional spatial rotations, would significantly increase the complexity of the equations. This model therefore focuses effectively on the essential dynamics, thereby reducing the complexity of both modeling and control design.

The effective description of flexible load deformation is the key link, and the assumed mode method is a widely used and effective method in this field [

23]. Based on Assumption 2, we regard the flexible load as a Euler–Bernoulli beam model [

24], and use the assumed mode method to characterize the elastic deformation of the flexible load. In order to simplify the above discussion before the establishment of the dynamic model, the following basic assumptions are introduced:

Assumption 1. Only the fixed-axis rotation of the flexible load in the XOY plane is considered.

Assumption 2. In view of the fact that the flexible load bar is far longer than its cross-sectional size, it is regarded as a slender beam.

Assumption 3. In the space environment, the influence of the gravity of the flexible load itself is ignored.

Assumption 4. The deformation of the flexible payload satisfies the conditions of inextensibility along the neutral axis and small deformations.

Based on the above assumptions and modeling method, the lateral deformation of the flexible load can be described as

where

is the i-th order modal function and

is the corresponding modal coordinate. Based on Assumption 4, the relationship between transverse deformation

and longitudinal deformation

can be expressed as

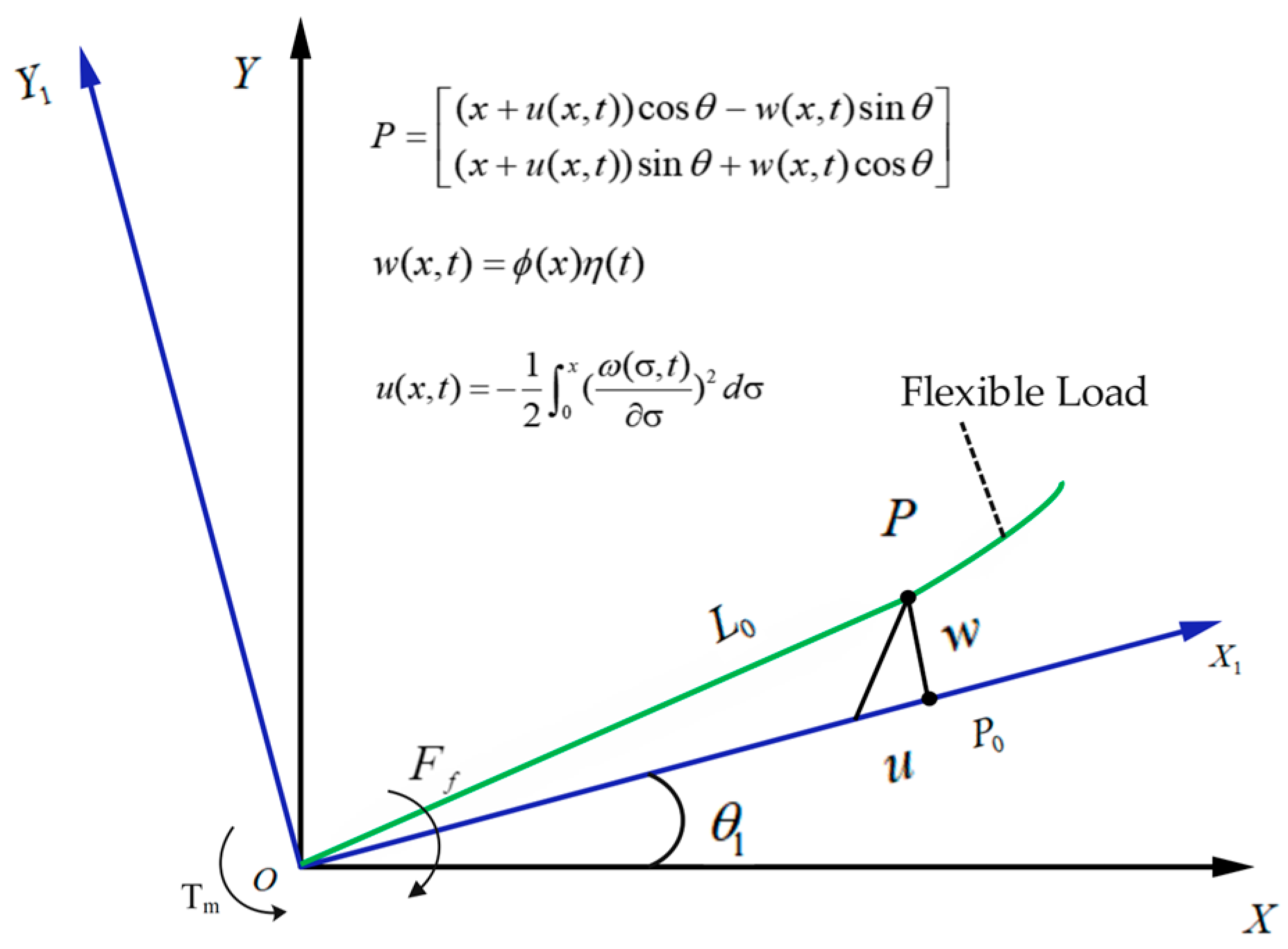

In order to further intuitively characterize the spatial flexible manipulator system considering both lateral and longitudinal deformation of the load, the static coordinate system O-XYZ fixed to the ground and the rotating coordinate system O-X

1Y

1Z

1 during the movement are established in

Figure 2. The Z

1 axis (rotation axis) coincides with the Z axis (rotation center of the manipulator), in which the motion of the flexible load can be decomposed into elastic deformation caused by the traction motion of the rotating coordinate system and rigid body motion relative to the rotating coordinate system.

The length of the flexible load is

, Tm is the input torque of the servo motor,

is the friction and

denotes the rotation angle of the flexible load. During motion, an arbitrary point

on the undeformed flexible link moves to position

after deformation, as illustrated in

Figure 2, and the P position of any point on the flexible load can be expressed as

The total kinetic energy of the system is composed of the kinetic energy of the load end and the kinetic energy of the motor end, as shown in the following equation:

In the formula,

is the linear density of the flexible load, and

is the moment of inertia of the motor. The space environment does not consider the gravitational potential energy. The potential energy of the system is composed of the elastic potential energy of the flexible load and the elastic potential energy of the flexible joint.

where

is the torsional stiffness coefficient of the joint,

denotes the elastic modulus,

represents the area moment of inertia of the cross-section, and

denotes the rotation angle of the flexible load, while

represents the rotation angle at the motor end. Part of the vibration mechanism of the system can be explained by the formula. Due to the existence of its own structural flexibility, the spatial flexible manipulator will store elastic potential energy during its movement. When the potential energy is released, it can cause system vibration.

The Lagrange function is introduced by the Lagrange second principle combined with the vibration theory. The dynamic equation of the spatial flexible manipulator system can be established as follows:

The generalized coordinate vector and generalized force vector are defined to describe the system motion.

Considering the dynamic characteristics of the system, the LuGre [

25] model with more comprehensive friction characteristics is selected to characterize the friction nonlinear term in the transmission system:

Among them, is the average friction deformation, is the friction stiffness coefficient, is the friction damping coefficient, is the viscous friction coefficient, is a nonlinear function describing the Stribeck effect, which is asymmetric and always greater than 0, is the friction velocity coefficient, is the coulomb friction torque, and is the static friction torque.

The choice of modal coordinate order during system modeling directly influences both the model’s accuracy and computational efficiency. Theoretically, retaining higher-order modes can more accurately approximate the dynamic characteristics of a continuous system, but it significantly increases control system complexity and computational burden. Research [

26] indicates that the dynamic response of a flexible manipulator is predominantly governed by its first-order mode, whose contribution substantially exceeds the combined effects of all higher-order modes. Furthermore, the deformation deviation between the two-dimensional deformation of the flexible load and the neglected nonlinear coupling terms is negligible. The study indicates that the first-order natural frequency of the flexible load (10–20 Hz) is significantly higher than the system’s dominant rotational motion frequency (0.1–0.3 Hz), demonstrating a clear frequency separation. As the natural frequencies of higher-order modes are even higher, their excitation energy during the system’s low-frequency motion is extremely limited. Furthermore, numerical analysis shows that under the given operating condition, the maximum amplitude of transverse deformation is on the order of 10

−2, while the longitudinal deformation amplitude is only on the order of 10

−5. This verifies that neglecting higher-order modes, nonlinear coupling terms, and longitudinal deformation does not significantly affect model accuracy. Therefore, retaining only the first-order mode is well-justified for dynamic analysis and control strategy design. Following this conclusion, this work retains the first-order mode while neglecting the coupling nonlinear terms. Integrated with the LuGre friction model, the dynamic equations of the spatial flexible manipulator system are derived as follows:

In the formula,

is the inertia matrix,

is the stiffness matrix,

is the disturbance term,

is the control input of the system. The specific parameters of the above formula are shown in the

Appendix A. In this paper, the LuGre friction model is primarily used to construct a high-fidelity simulation benchmark, accurately reflecting the complex friction characteristics of a real system. In terms of controller design, however, this friction is treated as a bounded nonlinear disturbance. It is compensated for online by the RBF neural network, thereby enhancing the robustness of the controller.

4. Simulation Analysis

To evaluate the control performance of the proposed strategy in a spatial flexible manipulator system, simulation studies are conducted for the Radial Basis Function neural network-based super-twisting algorithm (the legend is represented as STASMC + RBF). A simulation model is developed in MATLAB/Simulink. For comparison, conventional sliding mode control with a neural network (the legend is represented as SMC + RBF) and PID control (the legend is represented as PID) are implemented as benchmark controllers. The parameters used in the numerical simulations are listed in

Table 1. For the PID controller, the parameters were set as follows: proportional gain = 15, integral gain = 20, derivative gain = 5, and filter coefficient = 100. For the SMC with an RBF neural network, a conventional sliding surface was adopted, with its coefficient set to 0.5.

Owing to their lightweight long-link structure and substantial payload capacity, spatial flexible manipulators are prone to elastic deformation in the flexible load, which consequently induces end-point vibration. To prevent mechanical vibrations caused by the input rotation angle exciting the structural resonant frequency, a simply optimized sinusoidal function is adopted as the desired rotational speed input for the system’s servo motor. The remaining desired input parameters are determined using the angle-uncorrelated method [

26]. Under these operating conditions, simulation results for different control strategies are obtained.

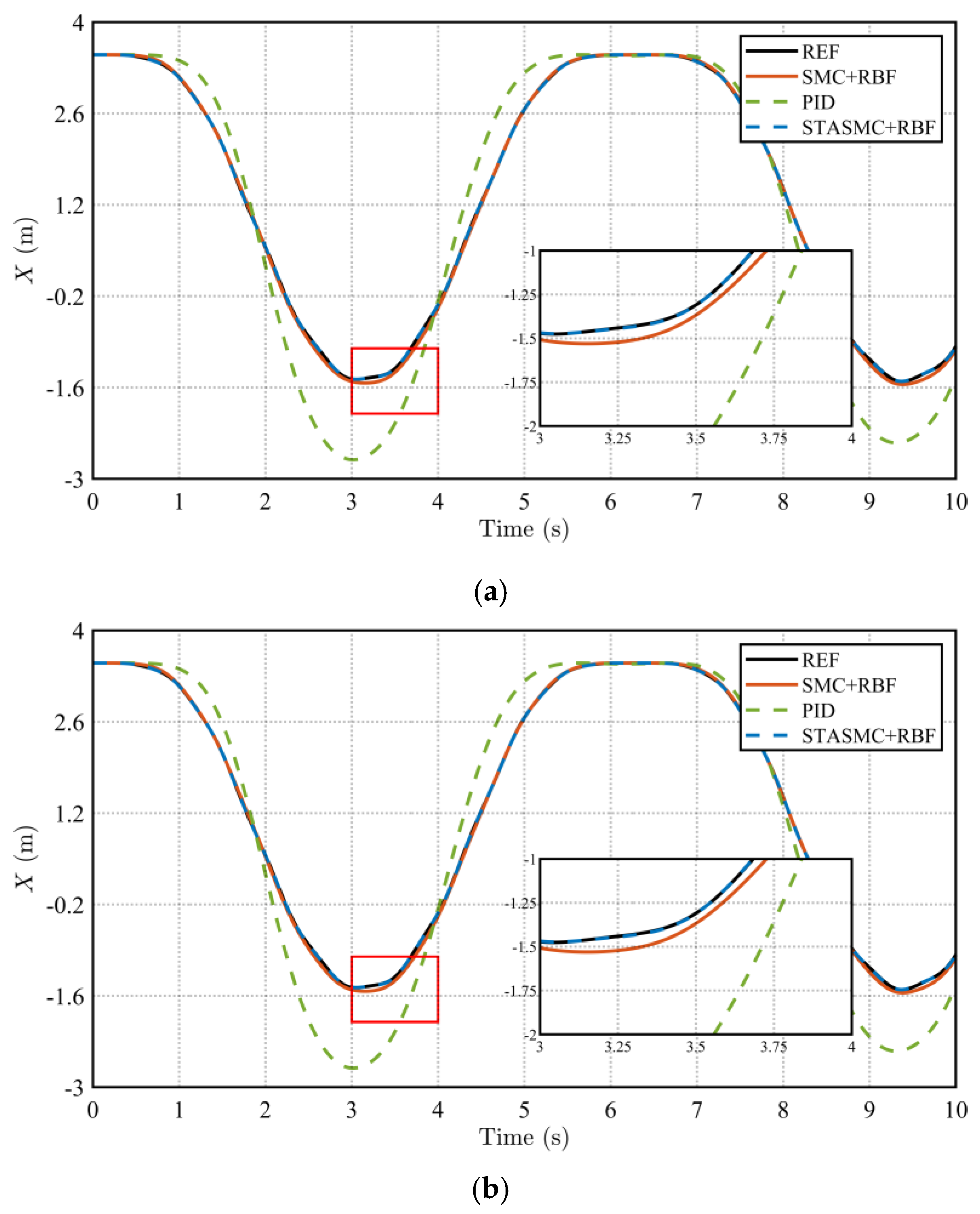

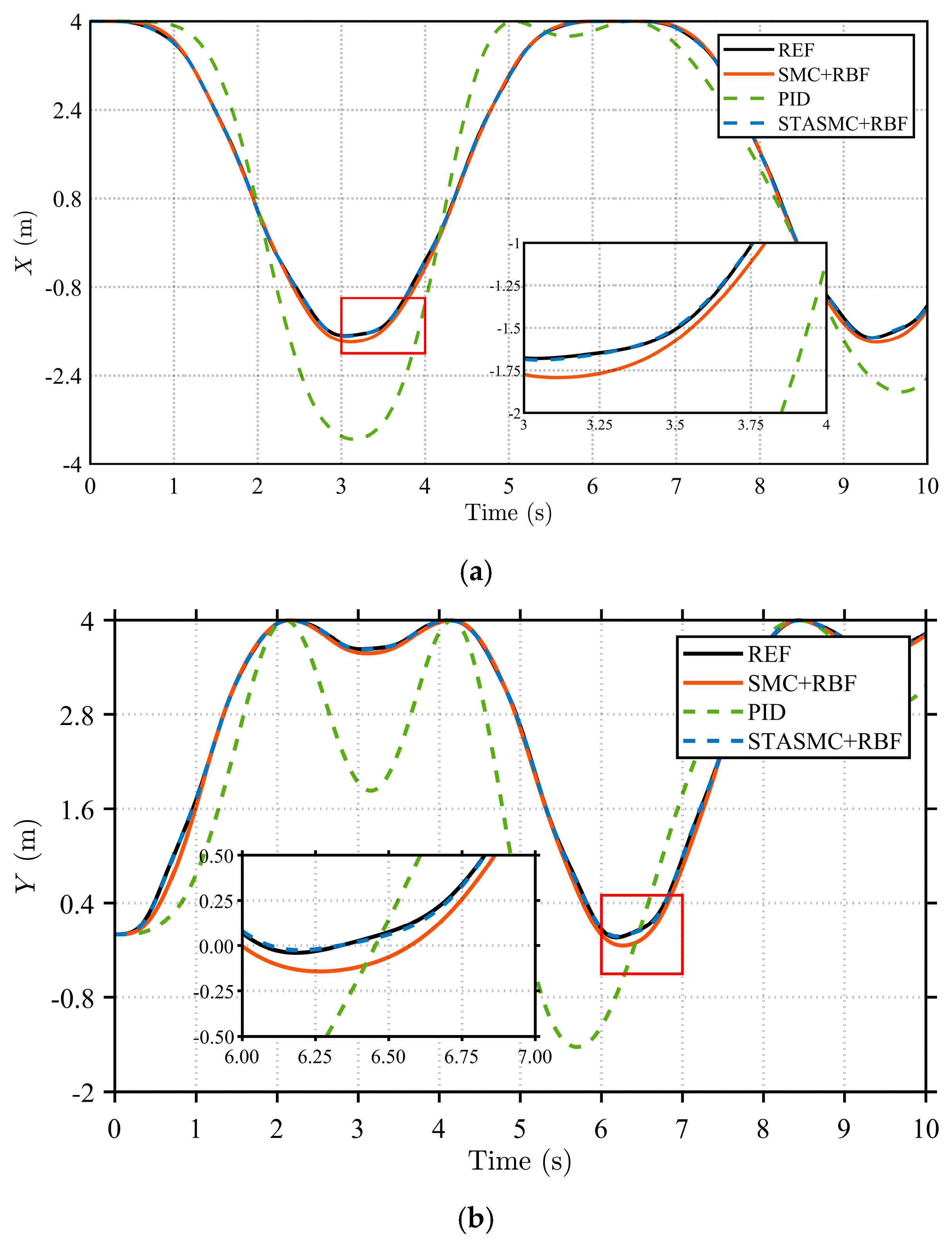

The trajectory tracking accuracy of the flexible load’s end-effector serves as a key metric for evaluating system control precision. The X and Y axis trajectories of the spatial flexible manipulator are illustrated in

Figure 4.

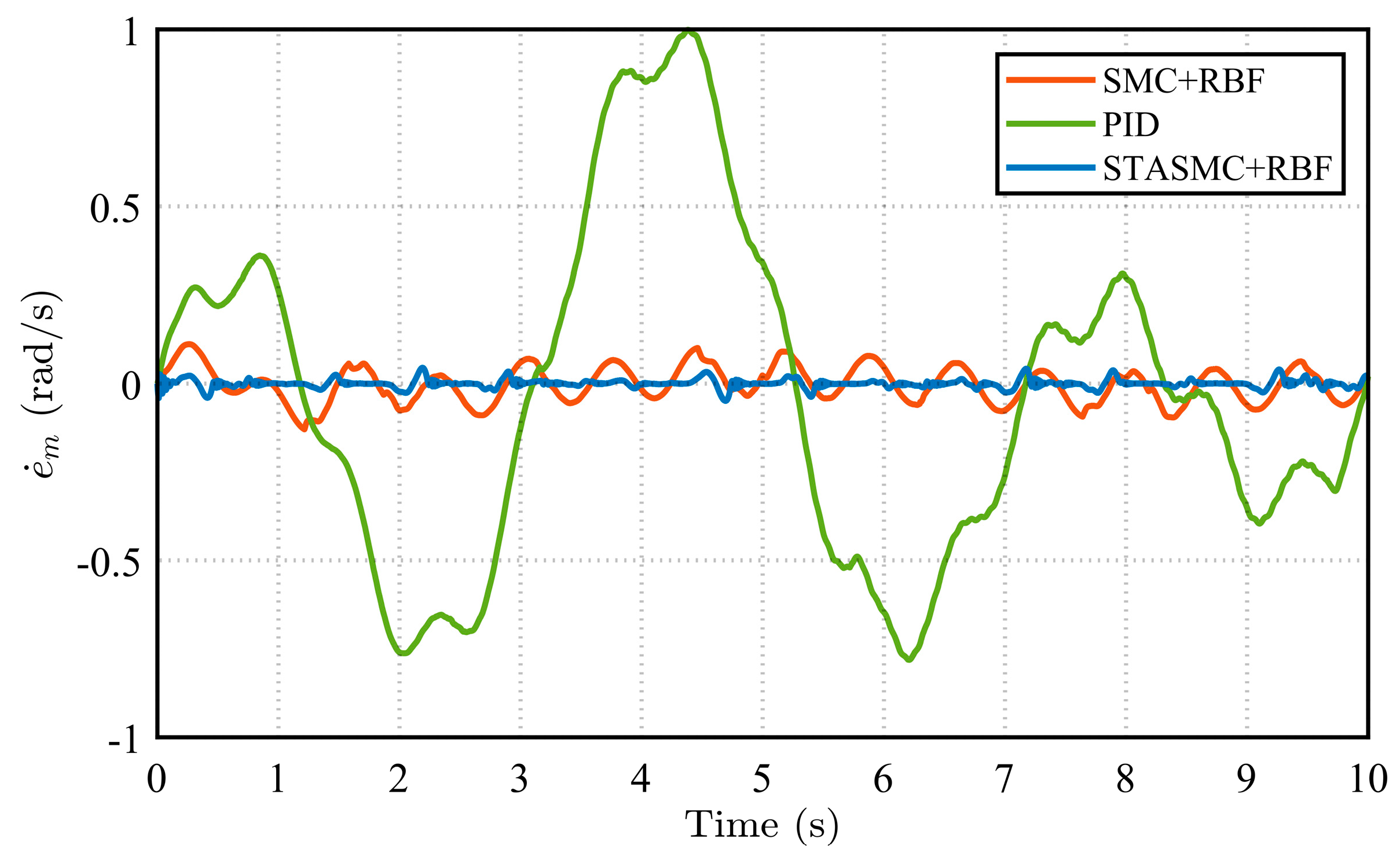

In

Figure 4, REF represents the desired trajectory. A comparison of the simulation results reveals clear discrepancies between the desired trajectory and the actual tracking trajectories under different control strategies. The PID control exhibits sustained and significant deviations in both the X and Y axis directions, with its trajectory consistently failing to align closely with the desired path. This reflects the inherent limitations of PID in handling complex nonlinear systems and disturbances. In contrast, the SMC strategy improves tracking performance to some extent; however, its deviation increases further during turning and acceleration phases. The STASMC + RBF strategy demonstrates superior trajectory tracking performance. Overall, the path tracked by STASMC + RBF almost coincides with the desired trajectory, showing no noticeable lag. Further observation of the local magnified view confirms that STASMC + RBF achieves precise tracking in both the X and Y axis directions without significant oscillation or deviation at turns. By comparison, the trajectory under SMC exhibits continuous minor deviations and jitter, indicating the inferior convergence of the sliding surface and disturbance rejection capability relative to the STASMC + RBF structure. As shown in

Figure 5, the proposed STASMC + RBF strategy maintains an excellent trajectory tracking performance across different operating conditions. To quantitatively evaluate accuracy and further highlight the advantages of the proposed strategy, the rotation angle error (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) and angular velocity error (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) at the flexible load end, as well as the rotation angle error (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) and angular velocity error (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) at the servo motor end, are compared for the three control strategies under the same operating condition. These metrics respectively reflect the disturbance suppression capability of the flexible load and the control precision of the actuator.

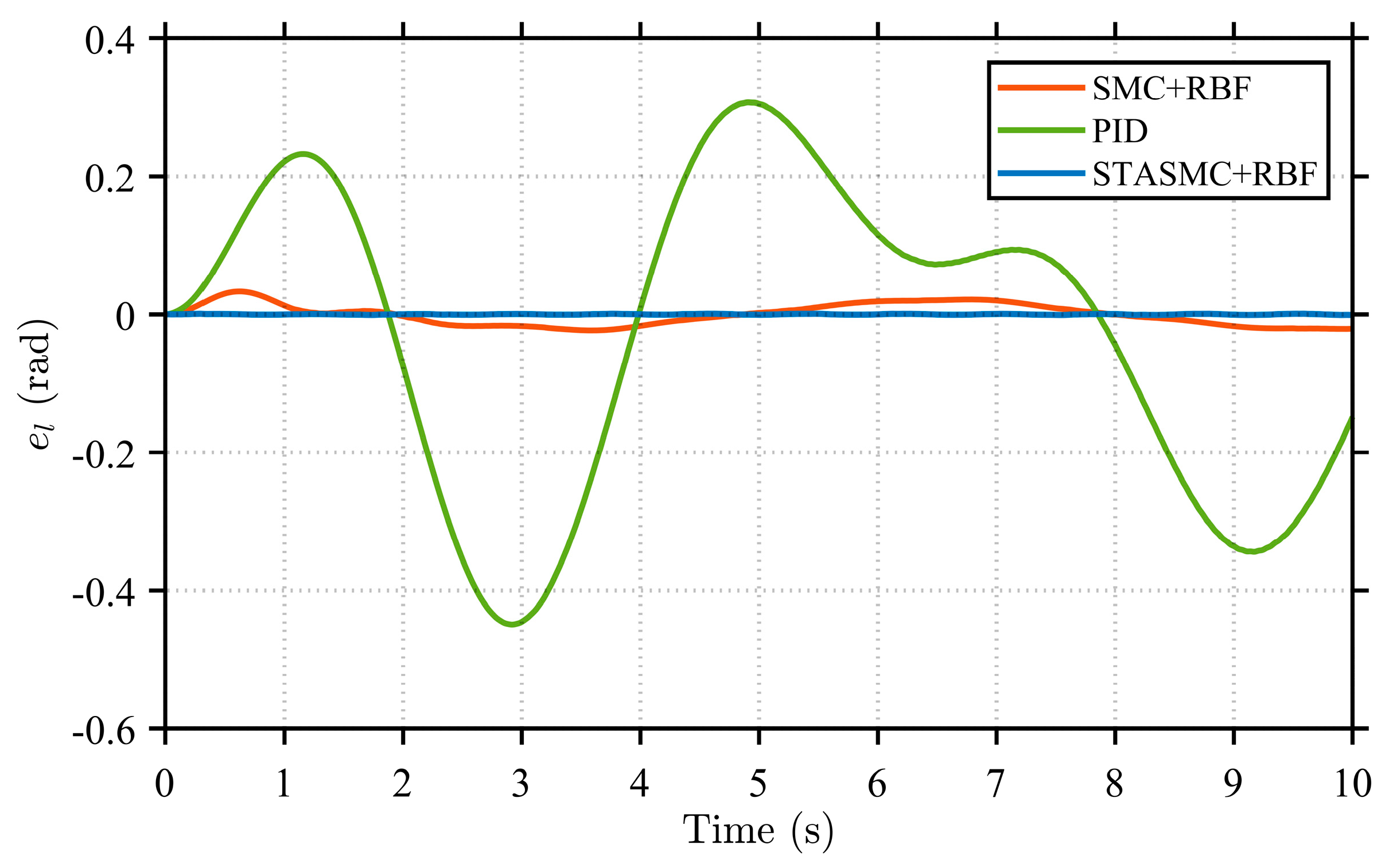

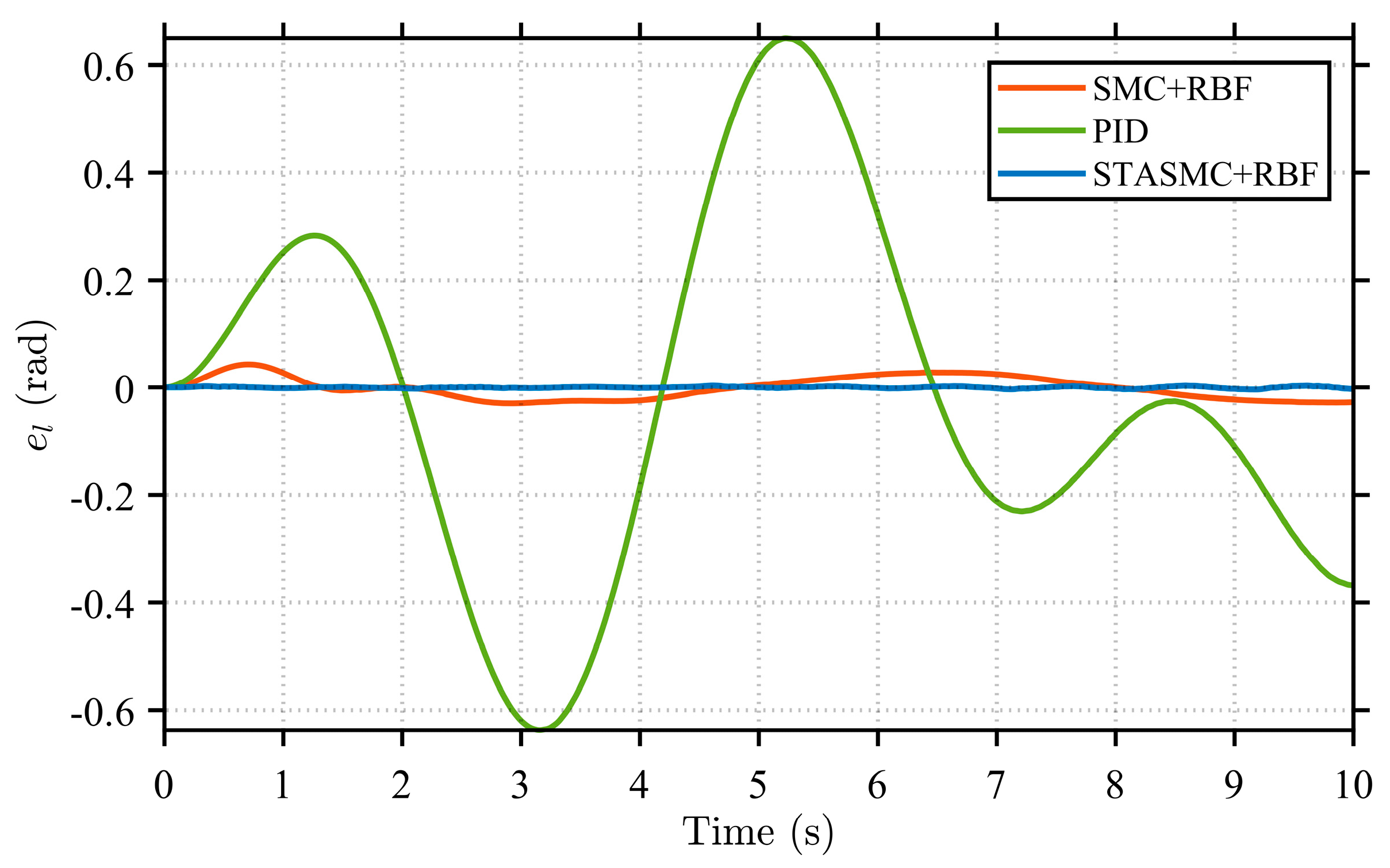

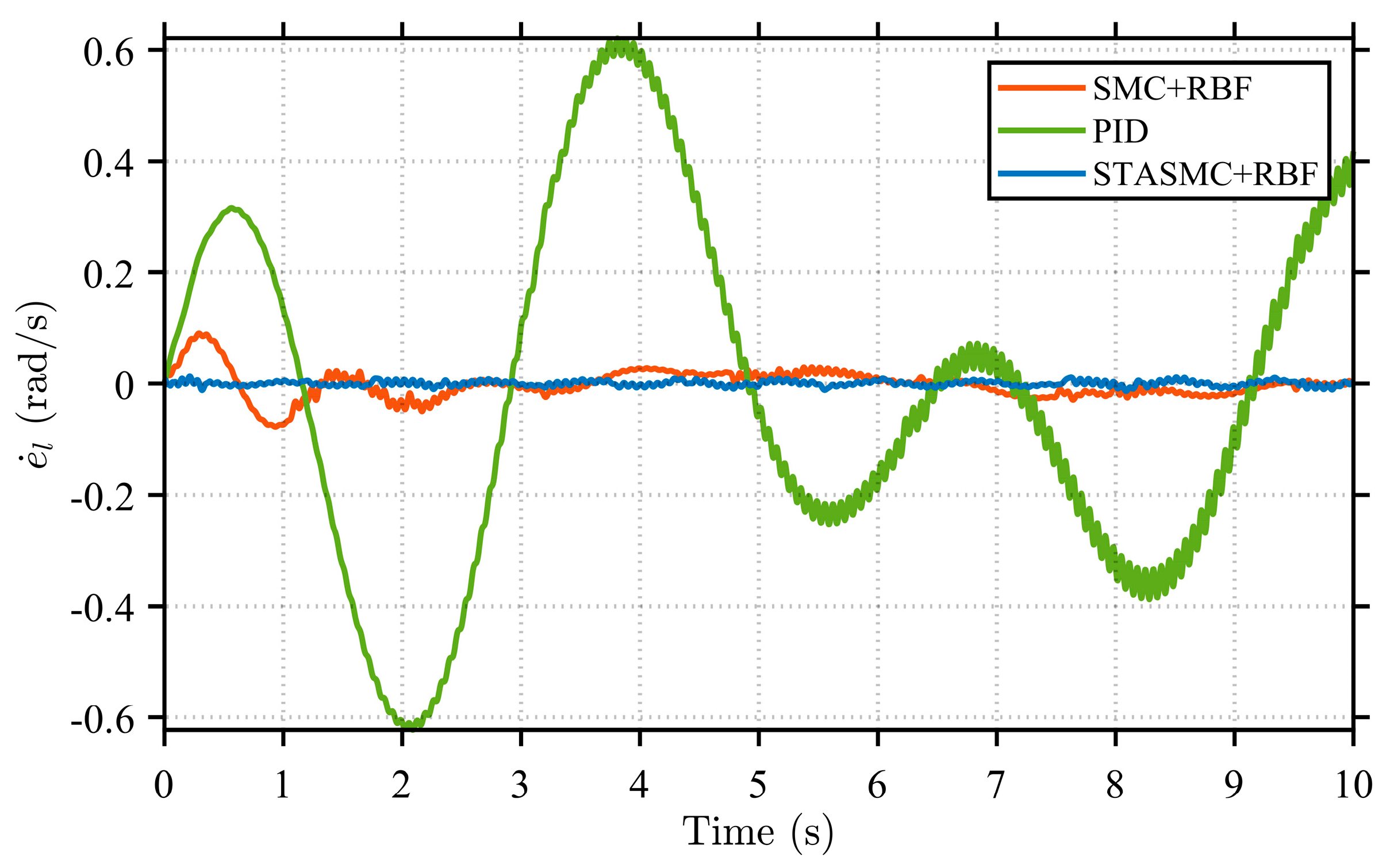

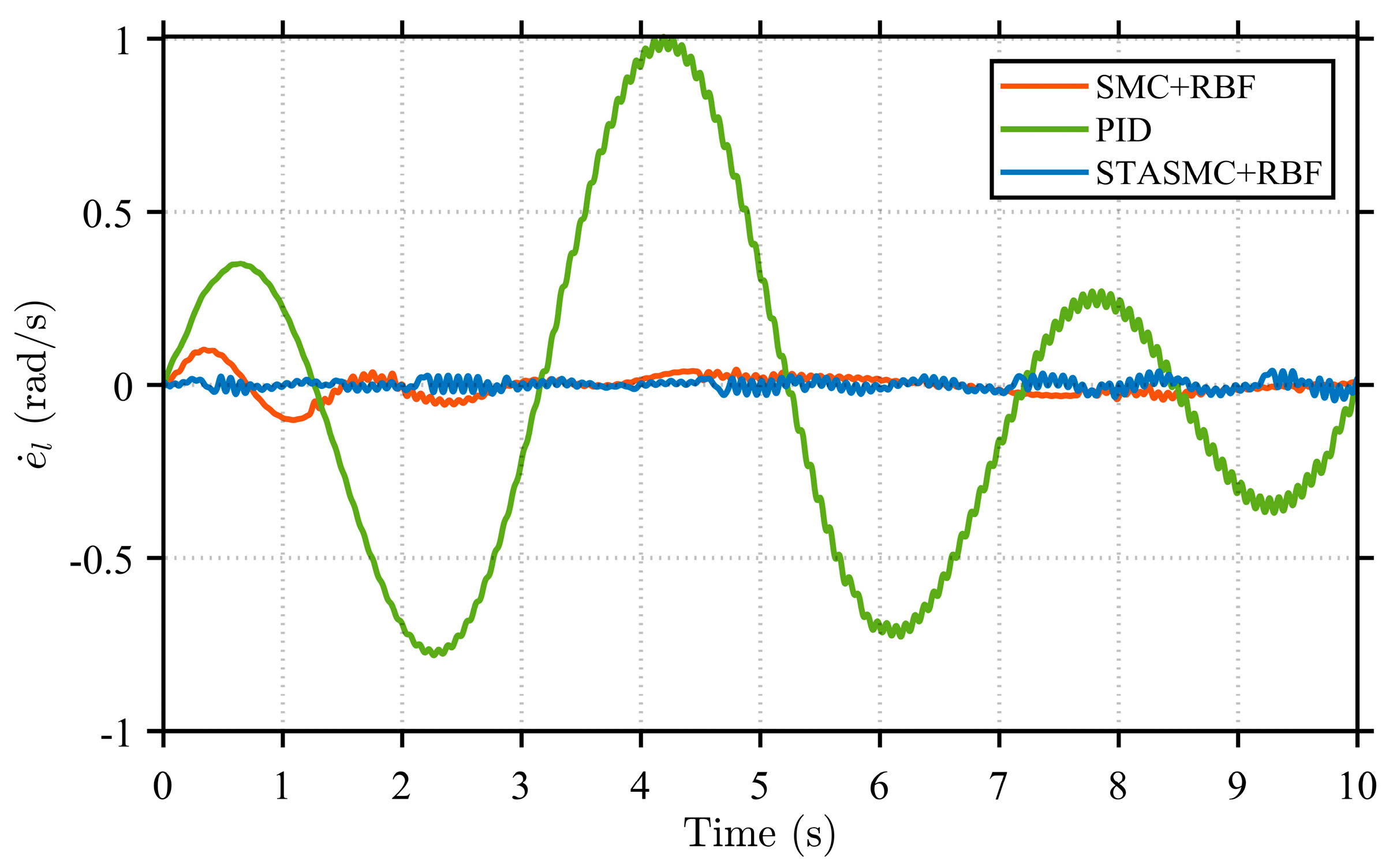

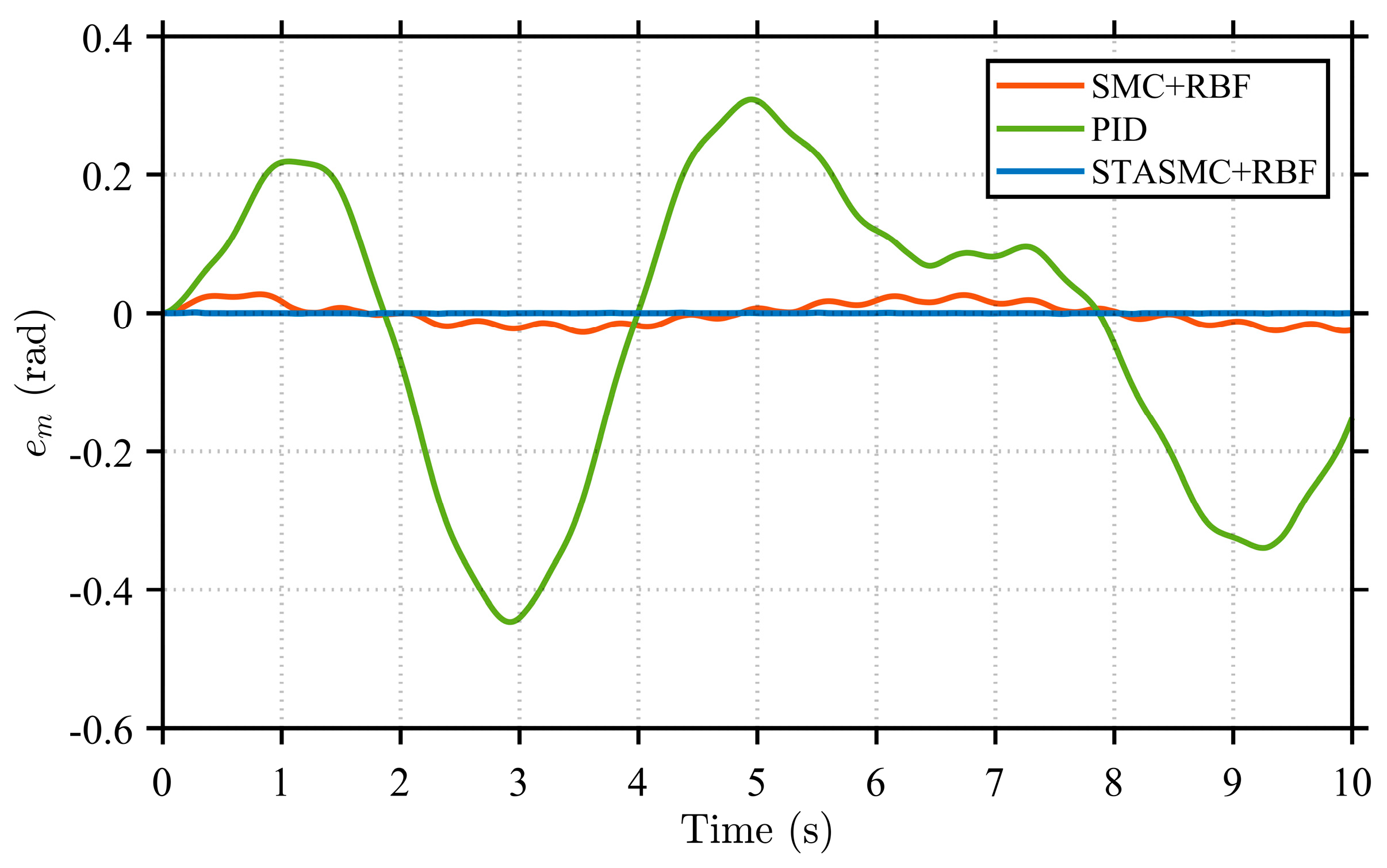

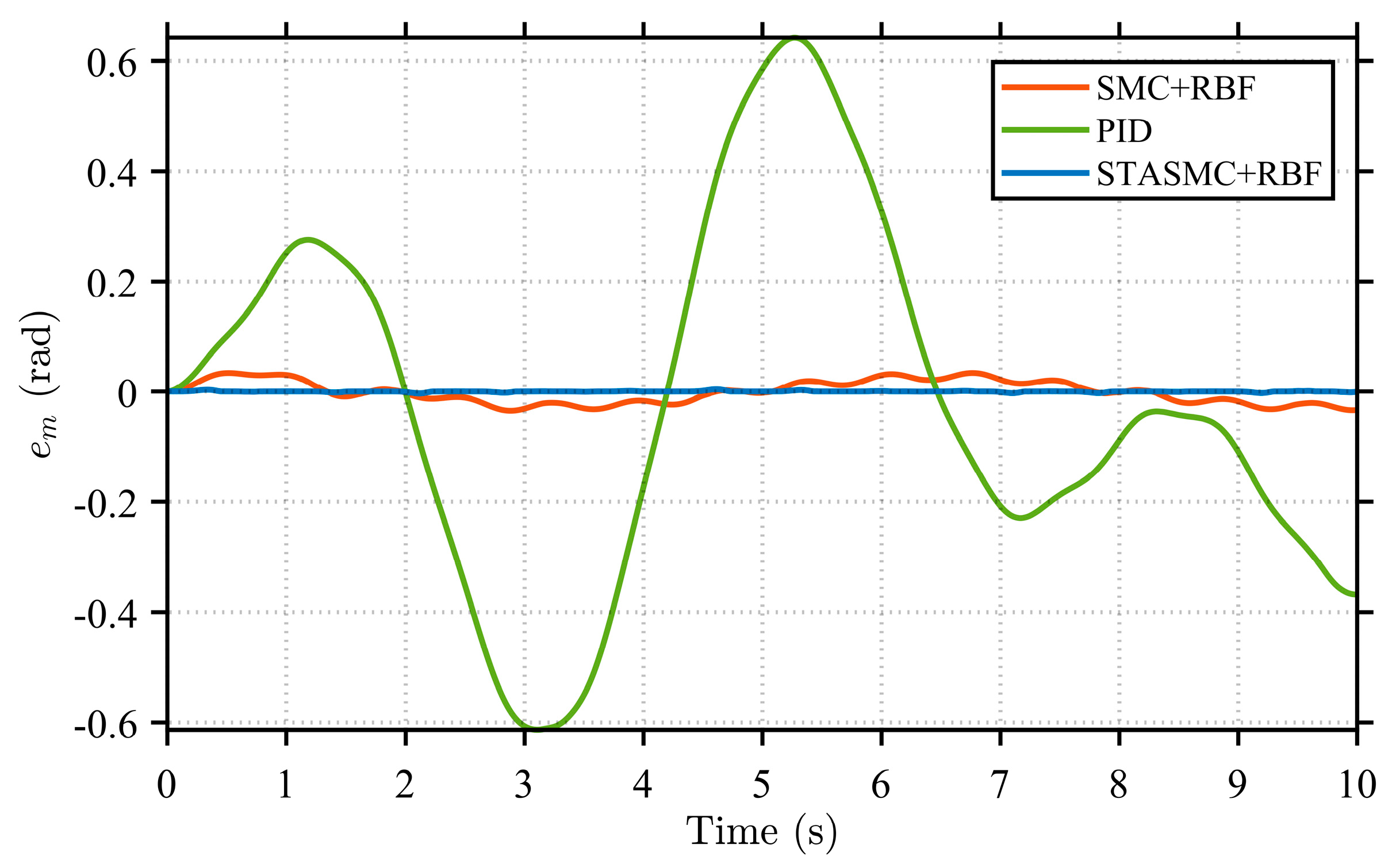

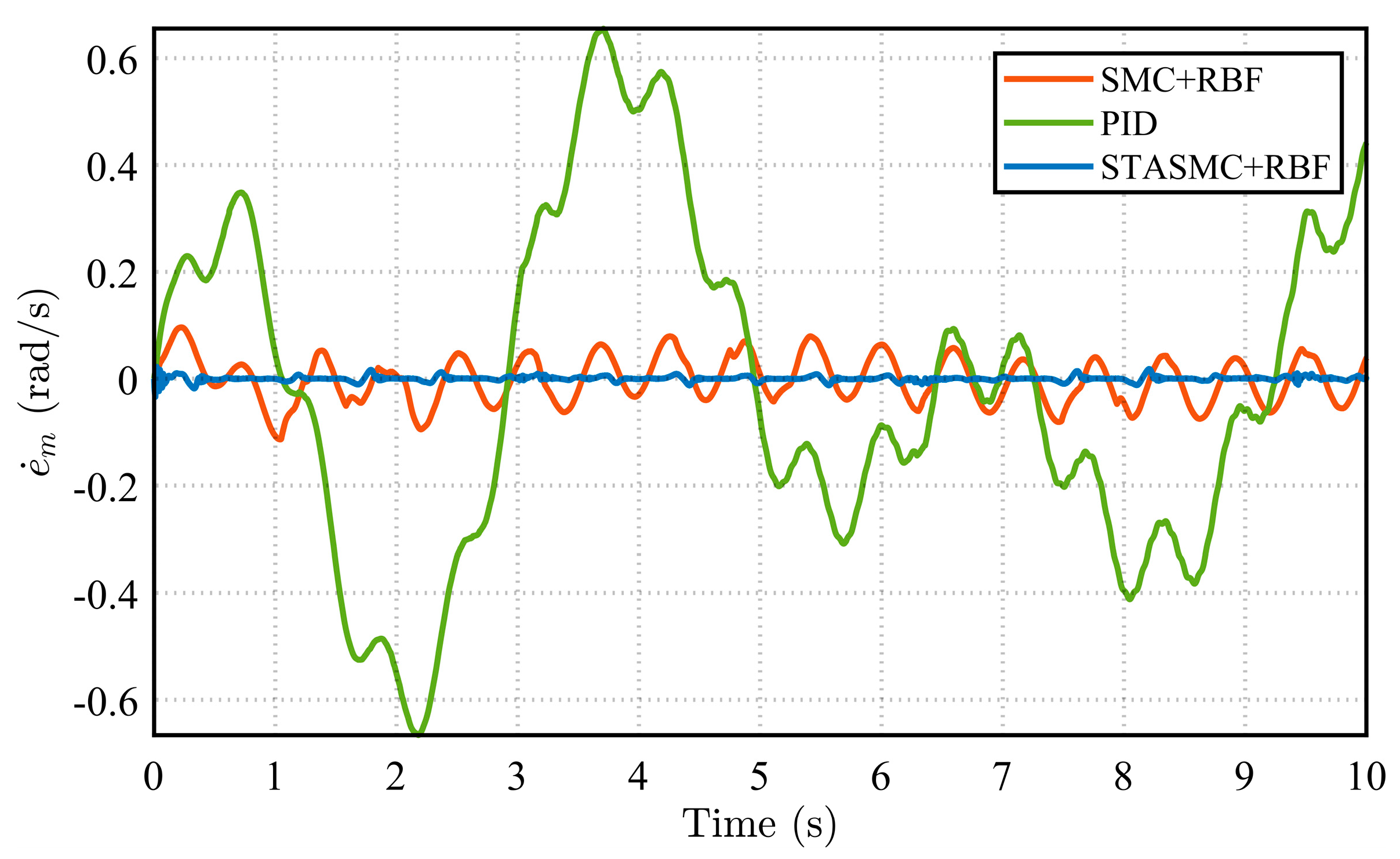

The rotation angle and angular velocity error curves at both the load end and motor end, shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, clearly demonstrate the performance differences among the control strategies. Regarding rotation angle errors, the PID control strategy exhibits significant deviations throughout the entire time range. Its error curves show considerable fluctuations with large amplitudes, presenting persistent asymmetric oscillations at both the load end and motor end. This observation further confirms the limited capability of the PID strategy in suppressing disturbances in nonlinear systems, resulting in relatively unstable system performance. In comparison, the SMC + RBF strategy exhibits relatively regular periodic fluctuations in its error curves, with reduced amplitude compared to the PID strategy. This indicates that its variable structure control mechanism enhances robustness against parameter variations and disturbances, demonstrating certain insensitivity characteristics. Additionally, with the adaptive compensation capability of the RBF neural network, the SMC + RBF strategy achieves the better identification and suppression of uncertainties in the system. However, the SMC + RBF strategy still exhibits some level of chattering, which is also reflected in the continuous fluctuations of its angular velocity error curves. Furthermore, the error performance of the three control strategies under various conditions is presented, with a focus on the angle and angular velocity errors of the flexible load. It can be observed that as the manipulator arm length increases, the amplitudes of both the steering angle error and the angular velocity error exhibit an increasing trend. This indicates intensified system vibration under the extended arm configuration. Despite this, the STASMC + RBF-based control strategy consistently demonstrates significantly narrower error bounds. In contrast, both the conventional SMC + RBF and PID strategies exhibit larger oscillation amplitudes and more pronounced fluctuations in steering angle error.

To quantitatively evaluate the advanced advantages of the proposed control strategy, this paper selects the rotation angle error

and the angular velocity error

at the load end for comparative analysis, as shown in

Table 2. The rotation angle error

directly determines the absolute positioning accuracy of the end-effector, serving as a key static parameter for evaluating trajectory tracking performance. In contrast, the angular velocity error

reflects the dynamic smoothness during motion, whose fluctuations are directly related to issues such as the residual oscillation of the flexible load and operational chattering.

Given that the preceding simulation results clearly show a significant performance gap (by orders of magnitude) between conventional PID control and the sliding-mode-based strategies for both error types, the comparison is focused on two RBF-enhanced sliding mode variants, namely, the conventional sliding mode control with RBF neural network (SMC + RBF) and the proposed super-twisting sliding mode control with RBF neural network (STASMC + RBF). This approach excludes the vastly underperforming PID baseline, allowing for a more precise examination of the unique improvements brought by the STASMC structure.

For quantitative comparison,

Table 2 lists the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) for both strategies under different operating conditions. RMSE is more sensitive to larger errors, effectively characterizing the dispersion of the error distribution, while MAE provides a robust estimate of the absolute error level. As the data in

Table 2 indicate, under the two conditions with different load lengths, the STASMC + RBF strategy exhibits significantly lower RMSE and MAE values for both el and el compared to the SMC + RBF strategy. Specifically, under Condition 1, STASMC + RBF reduces the RMSE of el by 96.3% and that of

by 82.3%. Under the more challenging Condition 2 (with increased arm length), it still achieves reductions of 91.4% and 60.8%, respectively. These quantitative results demonstrate that the STASMC + RBF strategy not only shows a clear advantage in improving end-point positioning accuracy, but is also highly effective in suppressing velocity fluctuations and vibrations. Furthermore, the strategy maintains superior performance under varying parameters (load length), demonstrating its enhanced robustness.

In summary, the STASMC + RBF control strategy demonstrates excellent performance in all aspects. Both its rotation angle and angular velocity error curves maintain minimal amplitudes throughout, with overall smoother variations and no significant chattering or sustained oscillations. By introducing integral operations, the super-twisting algorithm’s architecture suppresses high-frequency switching, leading to smooth disturbance compensation and output. Furthermore, the STASMC + RBF strategy shows good consistency in the error curves at both the load end and the motor end, indicating effective cooperative control between the two ends and improved overall tracking accuracy and synchronization performance. Therefore, it can be concluded that the RBF neural network-based super-twisting algorithm sliding mode control strategy achieves high control precision in reducing system chattering and minimizing rotation angle and velocity errors.