Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval

Abstract

1. Introduction

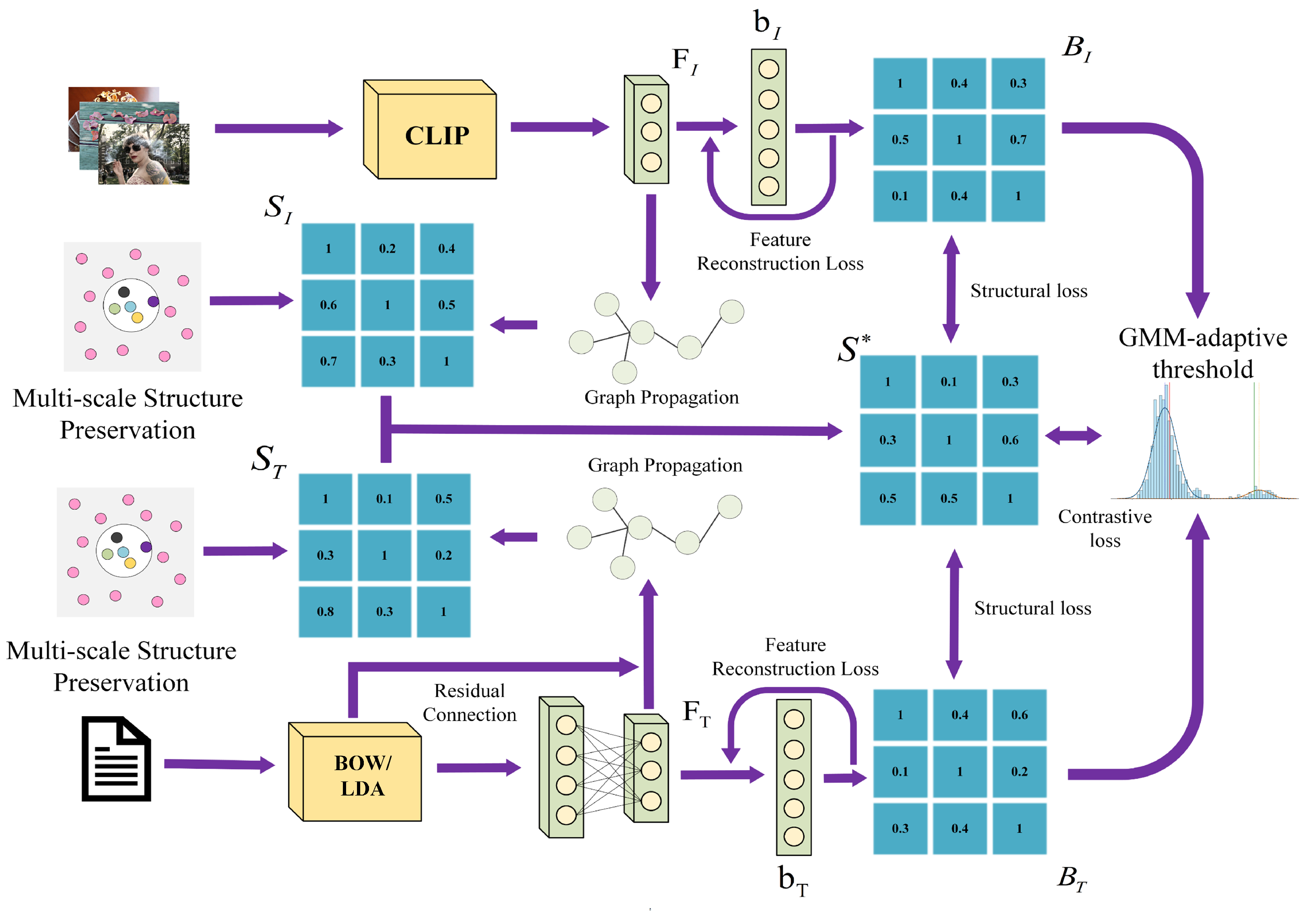

- The primary focus of this research is the design of a multi-scale similarity learning module guided by graph propagation, which generates a comprehensive semantic similarity matrix without the need for labeled data.

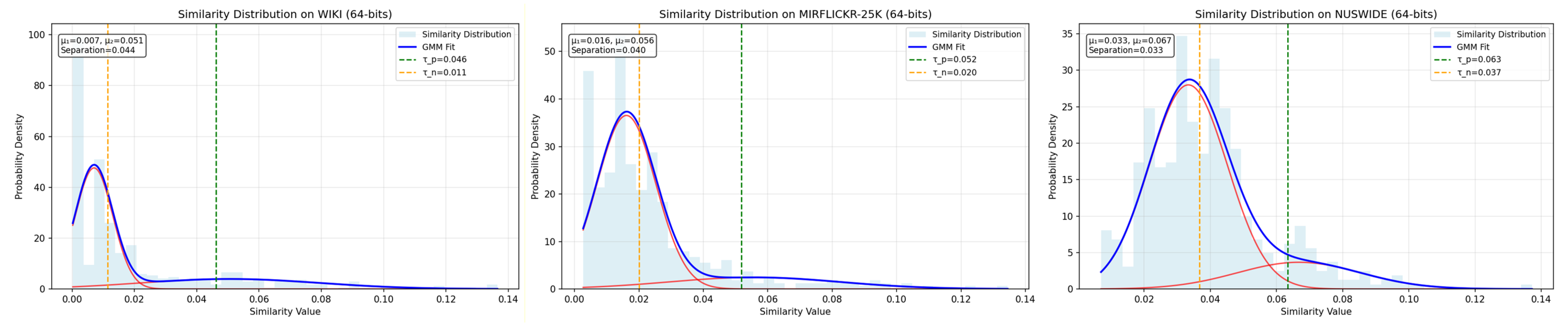

- We propose a hash contrastive learning module that establishes thresholds for positive and negative samples using GMM, providing more stable and distinguishable training signals for the entire model. This significantly enhances the semantic cohesion of the hash codes and improves retrieval accuracy.

- Comprehensive experiments carried out on three benchmark datasets verify that GPMCL can optimize hash functions more efficiently in comparison with other unsupervised cross-modal hashing algorithms.

2. Related Work

2.1. Supervised Methods

2.2. Unsupervised Methods

2.3. Multi-Modal Representation and Feature Fusion Paradigms

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. Problem Definition

3.2. Network Architecture

3.2.1. Image Network

3.2.2. Text Network

3.2.3. Model Training Optimization

3.2.4. Tensor Dimension Reference

3.3. Semantic Similarity Construction

3.3.1. Adaptive Graph Construction

3.3.2. Graph Propagation Process

3.3.3. Multi-Scale Structure Preservation

3.3.4. Semantic Similarity Fusion

3.3.5. Computational Complexity Analysis

- KNN construction: for distance computation and neighbor selection.

- Graph propagation: for layers of matrix multiplication.

- Multi-scale processing: for scales.

3.4. Hashing Learning

3.4.1. Semantic Hashing Construction

3.4.2. Structure Preserving

3.4.3. Feature Reconstruction Module

3.4.4. Adaptive Threshold Determination

3.4.5. Comparative Hashing Learning

3.5. Optimization

Algorithm 1 Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning |

Input: Training set ; batch size N; hash length ; hyperparameters , K. Output: Network parameters . 1: Initialize , parameters randomly. 2: Repeat 3: , update (). 4: Sample batch . 5: Extract features and construct enhanced similarity matrix with Equations (14)–(21). 6: Generate hash codes , and reconstruct features with Equations (22) and (23). 7: Compute losses: , , with Equations (24)–(32). 8: Update parameters via SGD with total loss . 9: Until convergence. 10: Return learned parameters. |

4. Experiment

4.1. DataSets

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Baseline Methods and Evaluation Metrics

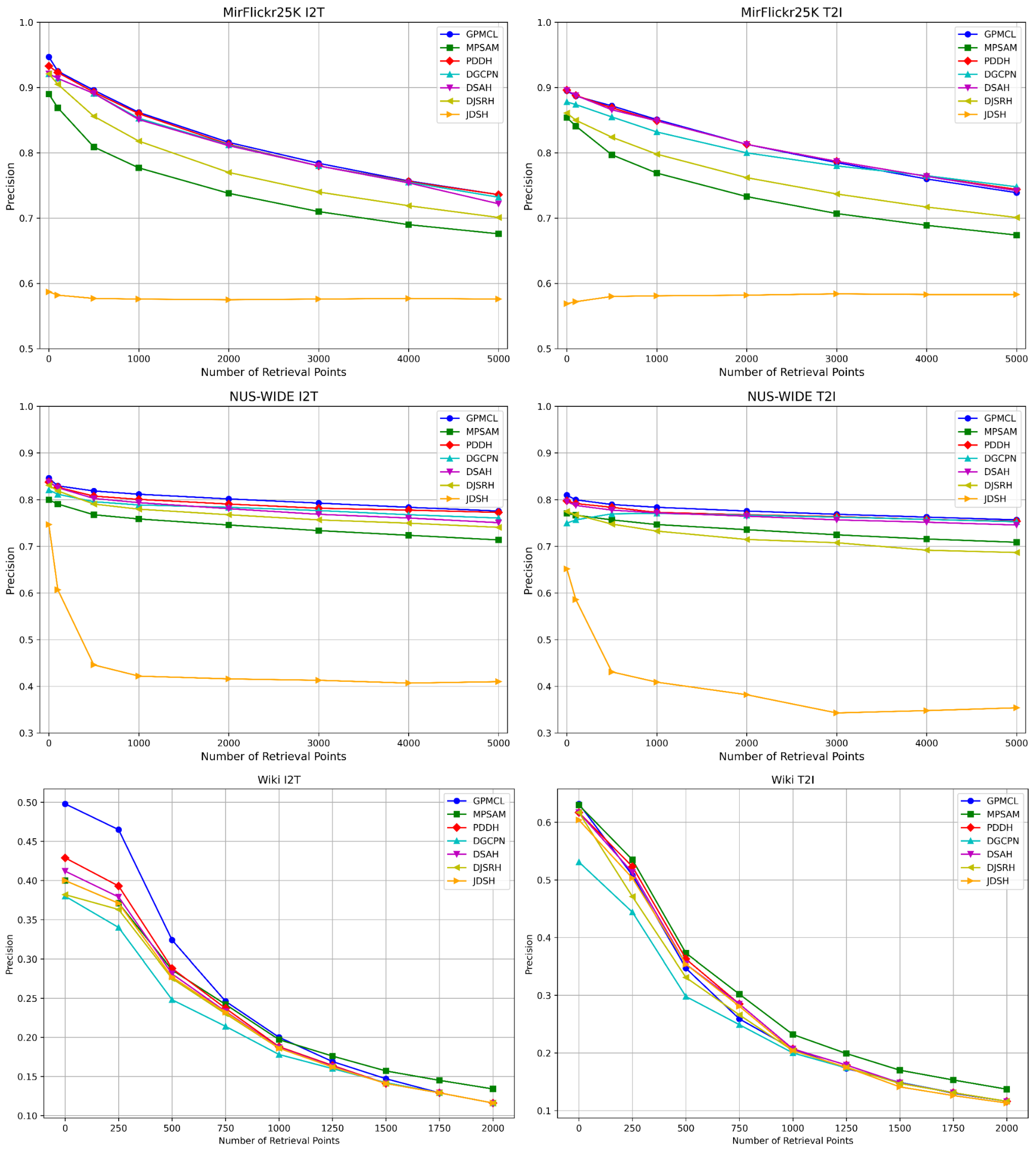

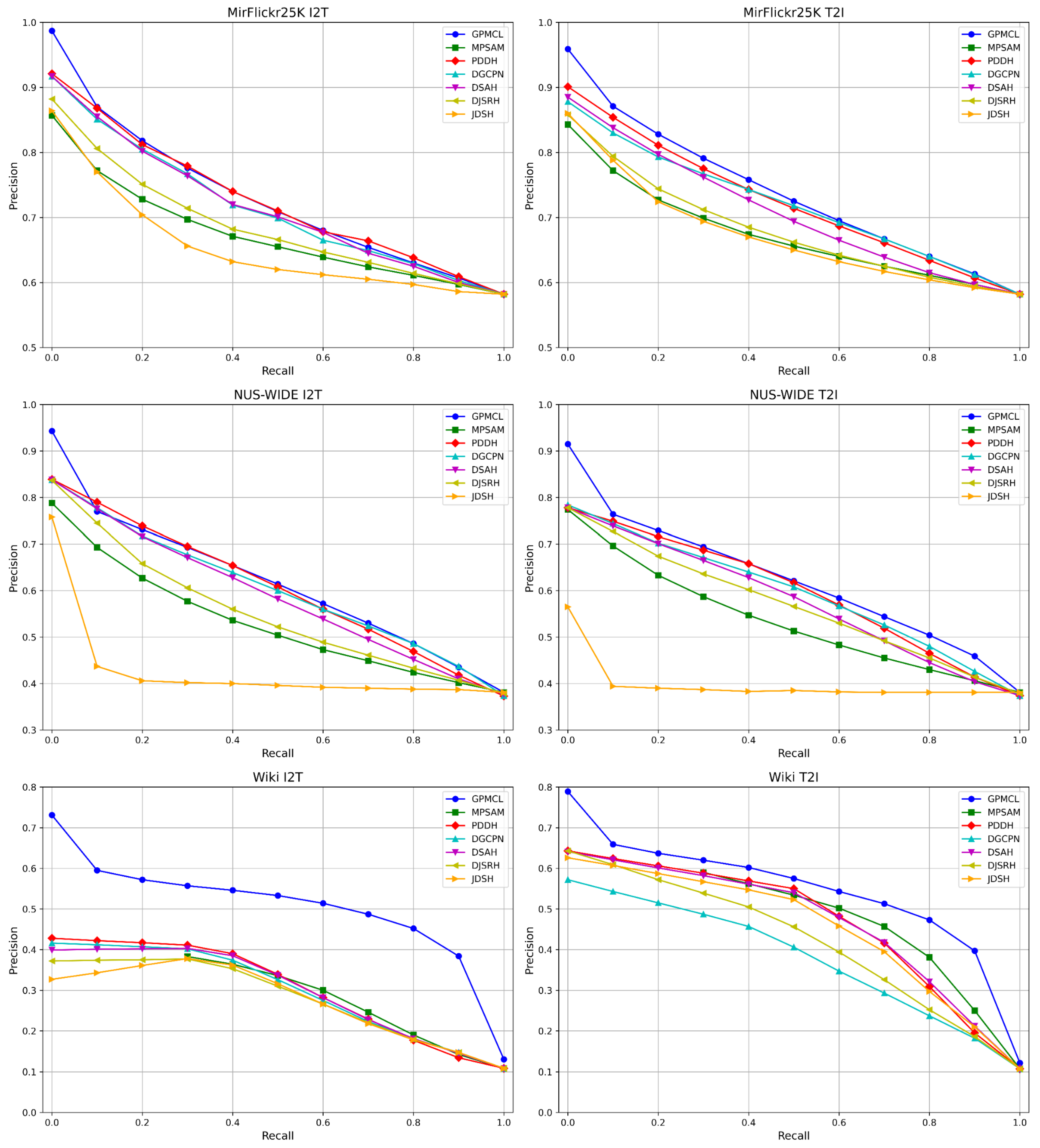

4.4. Precision Comparison

4.5. Ablation Study

- Architecture Variants:

- −

- GPMCL-AlexNet: Replaces the CLIP visual backbone with AlexNet to evaluate the impact of visual backbone representational capacity while maintaining the same text encoder.

- −

- GPMCL-VGG19: Replaces the CLIP visual backbone with the standard VGG19 network to create a controlled experimental setting for a fair comparison, while keeping the text encoder unchanged.

- Module Ablation Variants:

- −

- GPMCL-1: Removes the multi-scale structural preservation module. The model generates the similarity matrix solely through graph propagation.

- −

- GPMCL-2: Removes the entire structural preservation module, i.e., .

- −

- GPMCL-2(a): Removes the component from the structural preservation module, i.e., .

- −

- GPMCL-2(b): Removes the component from the structural preservation module, i.e., .

- −

- GPMCL-3: Removes the feature reconstruction module, i.e., .

- −

- GPMCL-4: Removes the contrastive hashing learning module, i.e., .

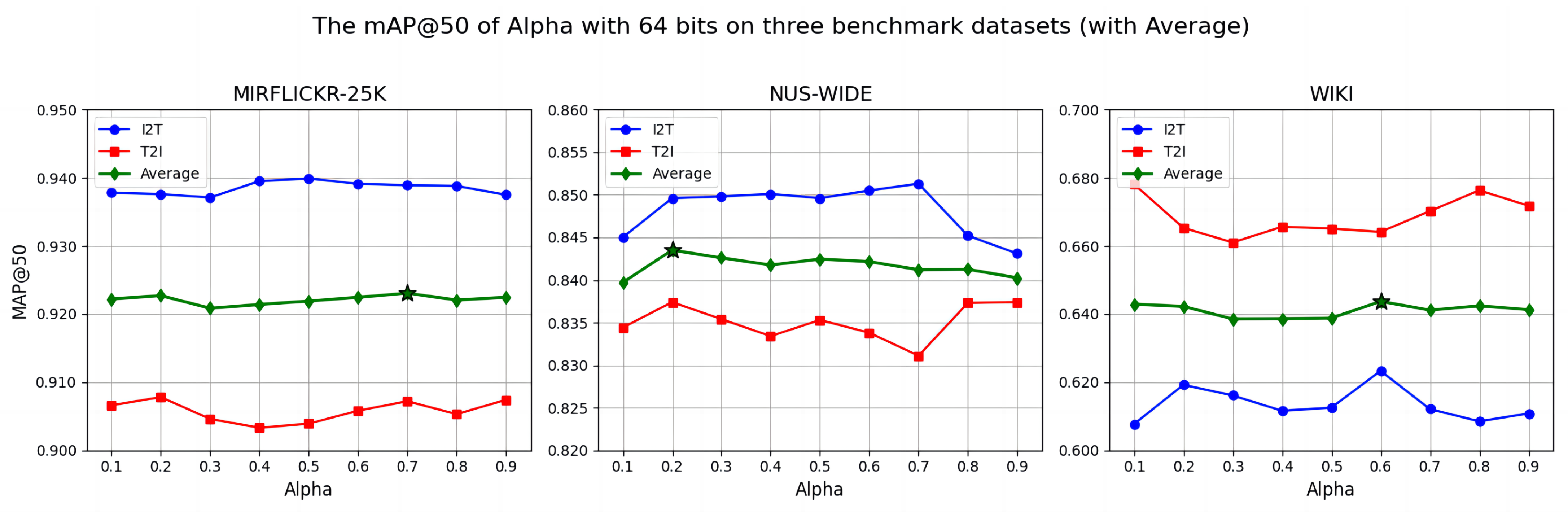

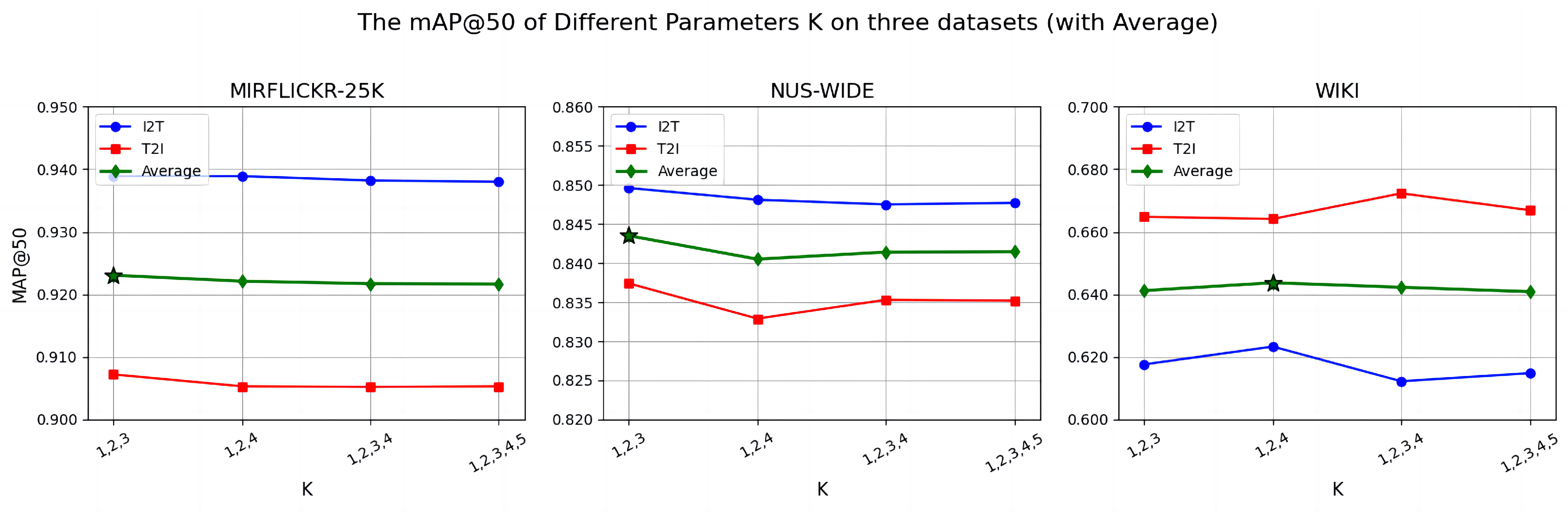

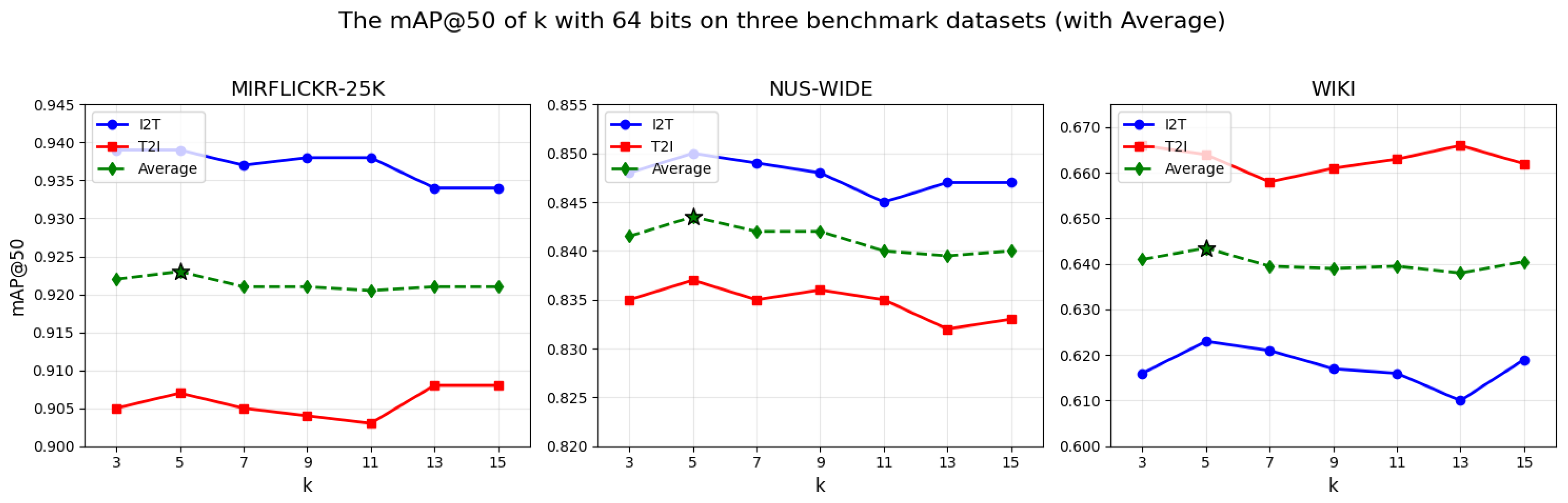

4.6. Parameter Sensitivity

- : the weighting coefficient for integrating image and text features into the similarity matrix.

- K: the predefined size of the multi-scale set within the similarity matrix.

- k: The graph sparsity hyperparameter. It specifies the number of nearest neighbors selected for each node during the construction of the similarity graph.

4.7. Efficiency and Complexity Analysis

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GPMCL | Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning |

| I2T | Image-to-Text |

| T2I | Text-to-Image |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| PR | Precision-Recall |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| CLIP | Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| BoW | Bag-of-Words |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

References

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal Machine Learning: A Survey and Taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasiwasia, N.; Costa Pereira, J.; Coviello, E.; Doyle, G.; Lanckriet, G.R.G.; Levy, R.; Vasconcelos, N. A new approach to cross-modal multimedia retrieval. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Firenze, Italy, 25–29 October 2010; pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Deep Supervised Hashing for Fast Image Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2064–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Feng, W.; Lin, Q.; Cao, G.; He, Z. A Review of Hashing Methods for Multimodal Retrieval. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 15377–15391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, F.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, H.T. Cross-Modal Retrieval: A Systematic Review of Methods and Future Directions. Proc. IEEE 2024, 112, 1716–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, F.; Ou, W.; You, X.; Peng, Q. Deep Adaptively-Enhanced Hashing With Discriminative Similarity Guidance for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 7255–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, R.C.; Mao, X.L.; Lin, Q.H.; Ji, W.J.; Qin, W.Z.; Wei, W.; Huang, H.Y. Unsupervised Cross-Modal Hashing via Semantic Text Mining. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 8946–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xu, K.; Xie, Y. Pseudo-label driven deep hashing for unsupervised cross-modal retrieval. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2023, 14, 3437–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Y. An Overview of Cross-Media Retrieval: Concepts, Methodologies, Benchmarks, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018, 28, 2372–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Ding, G.; Hu, M.; Wang, J. Semantics-preserving hashing for cross-view retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3864–3872. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Wang, K.; Shao, L. Supervised Matrix Factorization Hashing for Cross-Modal Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 3157–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Shen, F.; Yang, Y.; Shen, H.T.; Li, X. Learning Discriminative Binary Codes for Large-scale Cross-modal Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 2494–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.D.; Li, C.X.; Luo, X.; Nie, L.Q.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.S. SCRATCH: A Scalable Discrete Matrix Factorization Hashing Framework for Cross-Modal Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 30, 2262–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.Y.; Li, W.J. Deep Cross-Modal Hashing. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3270–3278. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.; Liu, X.; Lin, Z.; Hong, R.; Wang, M. Differentiable Cross-modal Hashing via Multimodal Transformers. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.; Qin, Q.; Dai, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Wang, C. Deep Semantic-Aware Proxy Hashing for Multi-Label Cross-Modal Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Y.; Torralba, A.; Fergus, R. Spectral hashing. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–10 December 2008; pp. 1753–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Udupa, R. Learning hash functions for cross-view similarity search. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Barcelona, Spain, 16–22 July 2011; pp. 1360–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Shen, H.T. Inter-media hashing for large-scale retrieval from heterogeneous data sources. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, New York, NY, USA, 22–27 June 2013; pp. 785–796. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Ding, G.; Guo, Y. Latent semantic sparse hashing for cross-modal similarity search. In Proceedings of the 37th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, 6–11 July 2014; pp. 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, C. Deep Joint-Semantics Reconstructing Hashing for Large-Scale Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3027–3035. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhan, Y.; Tao, D. Deep Graph-neighbor Coherence Preserving Network for Unsupervised Cross-modal Hashing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qian, S.; Guan, Y.; Zhan, J.; Ying, L. Joint-modal Distribution-based Similarity Hashing for Large-scale Unsupervised Deep Cross-modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, China, 25–30 July 2020; pp. 1379–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Wu, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Wang, W. Deep Semantic-Alignment Hashing for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Dublin, Ireland, 8–11 June 2020; pp. 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Zhu, H.; Lin, J.; Peng, D.; Zhao, Y.P.; Peng, X. Unsupervised Contrastive Cross-Modal Hashing. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 3877–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, J.; Yang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Qin, J. Unsupervised multi-perspective fusing semantic alignment for cross-modal hashing retrieval. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 63993–64014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Contreras, G.; Balderas-Díaz, S.; Serrano-Fernández, A.; Muñoz, A. Enhancing Sentiment Analysis on Social Media: Integrating Text and Metadata for Refined Insights. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Environments (IE), Málaga, Spain, 9–12 September 2024; pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Balderas-Díaz, S.; Guerrero-Contreras, G.; Ramírez-Vela, M.; Toribio-Camuñas, S.; Gay, N.C.; Reguera, A.M. Inclusive Education and Cultural Heritage Access: The LECTPAT Platform Multimodal Online Dictionary. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), Madrid, Spain, 25–27 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Csurka, G.; Dance, C.R.; Fan, L.; Willamowski, J.; Bray, C. Visual categorization with bags of keypoints. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Statistical Learning in Computer Vision, ECCV, Prague, Czech Republic, 11–14 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Atwood, J.; Towsley, D. Diffusion-convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; pp. 2001–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.A. Multi-Scale Contrastive Learning Networks for Graph Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications Technology and Computer Science (ACCTCS), Harbin, China, 22–24 March 2024; pp. 618–625. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Li, Y.; Ge, M.; Ma, L. CLIP-based fusion-modal reconstructing hashing for large-scale unsupervised cross-modal retrieval. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S. Contrastive Graph Convolutional Networks With Generative Adjacency Matrix. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.; Berthelot, D.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, Z.; Carlini, N.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C. FixMatch: Simplifying Semi-Supervised Learning with Consistency and Confidence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.07685. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Yu, P.S. HashNet: Deep Learning to Hash by Continuation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5609–5618. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Liu, H. Understanding the Behaviour of Contrastive Loss. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2495–2504. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Jia, M.; Lin, T.Y.; Song, Y.; Belongie, S.J. Class-Balanced Loss Based on Effective Number of Samples. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9260–9269. [Google Scholar]

- Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.04747. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Pereira, J.; Coviello, E.; Doyle, G.; Rasiwasia, N.; Lanckriet, G.R.G.; Levy, R.; Vasconcelos, N. On the Role of Correlation and Abstraction in Cross-Modal Multimedia Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 36, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiskes, M.J.; Lew, M.S. The MIR flickr retrieval evaluation. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Conference on Multimedia Information Retrieval, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30–31 October 2008; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, T.S.; Tang, J.; Hong, R.; Li, H.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, Y. NUS-WIDE: A real-world web image database from National University of Singapore. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Image and Video Retrieval, Santorini, Greece, 8–10 July 2009; Article No. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Kumar, S.; Chang, S.F. Learning to Hash for Indexing Big Data—A Survey. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.05472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Image | Text |

|---|---|---|

| Input | ||

| Feature Extraction | ||

| Hash Code | ||

| Reconstruction |

| Datasets | Wiki | MIR-Flickr-25K | NUS-WIDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database | 2866 | 20,015 | 186,577 |

| Training | 2173 | 5000 | 5000 |

| Testing | 693 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Image Feature | CLIP-ViT-B/16 | CLIP-ViT-B/16 | CLIP-ViT-B/16 |

| Text Feature | LDA (10-dim) | BoW (1386-dim) | BoW (1000-dim) |

| Task | Method | MIR-Flickr-25K | NUS-WIDE | Wiki | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 Bits | 32 Bits | 64 Bits | 128 Bits | 16 Bits | 32 Bits | 64 Bits | 128 Bits | 16 Bits | 32 Bits | 64 Bits | 128 Bits | ||

| I2T | DJSRH [21] | 0.810 | 0.843 | 0.862 | 0.876 | 0.724 | 0.773 | 0.798 | 0.817 | 0.388 | 0.403 | 0.412 | 0.421 |

| JDSH [23] | 0.832 | 0.853 | 0.882 | 0.892 | 0.736 | 0.793 | 0.832 | 0.835 | 0.313 | 0.432 | 0.430 | 0.447 | |

| DGCPN [22] | 0.852 | 0.867 | 0.892 | 0.905 | 0.789 | 0.814 | 0.825 | 0.848 | 0.425 | 0.437 | 0.441 | 0.457 | |

| DSAH [24] | 0.863 | 0.877 | 0.895 | 0.903 | 0.775 | 0.805 | 0.818 | 0.827 | 0.416 | 0.430 | 0.438 | 0.445 | |

| PDDH [8] | – | 0.915 | 0.929 | 0.940 | – | 0.824 | 0.841 | 0.856 | – | 0.464 | 0.467 | 0.467 | |

| MPSAM [26] | 0.847 | 0.864 | 0.874 | 0.887 | 0.758 | 0.784 | 0.805 | 0.820 | 0.412 | 0.421 | 0.425 | 0.428 | |

| GPMCL | 0.901 | 0.922 | 0.936 | 0.943 | 0.800 | 0.828 | 0.847 | 0.858 | 0.598 | 0.613 | 0.625 | 0.619 | |

| T2I | DJSRH [21] | 0.786 | 0.822 | 0.835 | 0.847 | 0.712 | 0.744 | 0.771 | 0.789 | 0.611 | 0.635 | 0.646 | 0.658 |

| JDSH [23] | 0.825 | 0.864 | 0.878 | 0.880 | 0.721 | 0.795 | 0.794 | 0.804 | 0.379 | 0.590 | 0.632 | 0.651 | |

| DGCPN [22] | 0.831 | 0.858 | 0.875 | 0.884 | 0.742 | 0.767 | 0.783 | 0.808 | 0.618 | 0.626 | 0.632 | 0.654 | |

| DSAH [24] | 0.846 | 0.860 | 0.881 | 0.882 | 0.770 | 0.790 | 0.804 | 0.815 | 0.644 | 0.650 | 0.660 | 0.662 | |

| PDDH [8] | – | 0.890 | 0.901 | 0.898 | – | 0.792 | 0.797 | 0.797 | – | 0.635 | 0.652 | 0.649 | |

| MPSAM [26] | 0.849 | 0.855 | 0.858 | 0.874 | 0.761 | 0.776 | 0.789 | 0.791 | 0.622 | 0.642 | 0.644 | 0.653 | |

| GPMCL | 0.876 | 0.899 | 0.907 | 0.911 | 0.789 | 0.823 | 0.836 | 0.843 | 0.640 | 0.657 | 0.662 | 0.666 | |

| Task | Metric | Hash Code Length | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 Bits | 32 Bits | 64 Bits | 128 Bits | ||

| I2T | Seed 1 | 0.896 | 0.926 | 0.939 | 0.944 |

| Seed 42 | 0.905 | 0.923 | 0.937 | 0.940 | |

| Seed 123 | 0.898 | 0.923 | 0.938 | 0.945 | |

| Seed 999 | 0.898 | 0.920 | 0.936 | 0.943 | |

| Seed 2025 | 0.908 | 0.919 | 0.930 | 0.943 | |

| Mean | 0.9010 | 0.9222 | 0.9360 | 0.9430 | |

| Std | 0.0049 | 0.0027 | 0.0034 | 0.0018 | |

| 95% CI | ±0.0061 | ±0.0034 | ±0.0042 | ±0.0022 | |

| Final Report | 0.901 ± 0.005 | 0.922 ± 0.003 | 0.936 ± 0.003 | 0.943 ± 0.002 | |

| T2I | Seed 1 | 0.877 | 0.898 | 0.907 | 0.909 |

| Seed 42 | 0.870 | 0.898 | 0.904 | 0.911 | |

| Seed 123 | 0.876 | 0.897 | 0.903 | 0.909 | |

| Seed 999 | 0.874 | 0.900 | 0.908 | 0.916 | |

| Seed 2025 | 0.882 | 0.900 | 0.911 | 0.909 | |

| Mean | 0.8758 | 0.8986 | 0.9066 | 0.9108 | |

| Std | 0.0045 | 0.0013 | 0.0033 | 0.0033 | |

| 95% CI | ±0.0056 | ±0.0016 | ±0.0041 | ±0.0041 | |

| Final Report | 0.876 ± 0.004 | 0.899 ± 0.001 | 0.907 ± 0.003 | 0.911 ± 0.003 | |

| Task | Metric | Hash Code Length | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 Bits | 32 Bits | 64 Bits | 128 Bits | ||

| I2T | Seed 1 | 0.799 | 0.830 | 0.850 | 0.858 |

| Seed 42 | 0.801 | 0.828 | 0.845 | 0.861 | |

| Seed 123 | 0.797 | 0.826 | 0.851 | 0.857 | |

| Seed 999 | 0.802 | 0.826 | 0.844 | 0.857 | |

| Seed 2025 | 0.800 | 0.832 | 0.846 | 0.859 | |

| Mean | 0.7998 | 0.8284 | 0.8472 | 0.8584 | |

| Std | 0.0019 | 0.0024 | 0.0028 | 0.0015 | |

| 95% CI | ±0.0024 | ±0.0030 | ±0.0035 | ±0.0019 | |

| Final Report | 0.800 ± 0.002 | 0.828 ± 0.002 | 0.847 ± 0.003 | 0.858 ± 0.001 | |

| T2I | Seed 1 | 0.805 | 0.823 | 0.837 | 0.840 |

| Seed 42 | 0.758 | 0.822 | 0.840 | 0.839 | |

| Seed 123 | 0.799 | 0.820 | 0.831 | 0.846 | |

| Seed 999 | 0.791 | 0.825 | 0.835 | 0.845 | |

| Seed 2025 | 0.792 | 0.825 | 0.836 | 0.846 | |

| Mean | 0.7890 | 0.8230 | 0.8358 | 0.8432 | |

| Std | 0.0195 | 0.0021 | 0.0033 | 0.0036 | |

| 95% CI | ±0.0242 | ±0.0026 | ±0.0041 | ±0.0045 | |

| Final Report | 0.789 ± 0.020 | 0.823 ± 0.002 | 0.836 ± 0.003 | 0.843 ± 0.004 | |

| Task | Metric | Hash Code Length | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 Bits | 32 Bits | 64 Bits | 128 Bits | ||

| I2T | Seed 1 | 0.593 | 0.612 | 0.623 | 0.617 |

| Seed 42 | 0.595 | 0.614 | 0.633 | 0.624 | |

| Seed 123 | 0.598 | 0.615 | 0.622 | 0.617 | |

| Seed 999 | 0.604 | 0.617 | 0.623 | 0.615 | |

| Seed 2025 | 0.600 | 0.606 | 0.625 | 0.621 | |

| Mean | 0.5980 | 0.6128 | 0.6252 | 0.6188 | |

| Std | 0.0043 | 0.0038 | 0.0046 | 0.0036 | |

| 95% CI | ±0.0053 | ±0.0047 | ±0.0057 | ±0.0045 | |

| Final Report | 0.598 ± 0.004 | 0.613 ± 0.004 | 0.625 ± 0.005 | 0.619 ± 0.004 | |

| T2I | Seed 1 | 0.637 | 0.653 | 0.664 | 0.665 |

| Seed 42 | 0.639 | 0.665 | 0.653 | 0.667 | |

| Seed 123 | 0.635 | 0.649 | 0.668 | 0.664 | |

| Seed 999 | 0.647 | 0.662 | 0.655 | 0.665 | |

| Seed 2025 | 0.644 | 0.654 | 0.668 | 0.671 | |

| Mean | 0.6404 | 0.6566 | 0.6616 | 0.6664 | |

| Std | 0.0050 | 0.0074 | 0.0066 | 0.0027 | |

| 95% CI | ±0.0062 | ±0.0092 | ±0.0082 | ±0.0034 | |

| Final Report | 0.640 ± 0.005 | 0.657 ± 0.007 | 0.662 ± 0.007 | 0.666 ± 0.003 | |

| Task | Method | MIR-Flickr-25K | NUS-WIDE | Wiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2T | GPMCL | 0.939 | 0.850 | 0.623 |

| JDSH(AlexNet) | 0.882 | 0.832 | 0.430 | |

| DGCPN(VGG19) | 0.892 | 0.825 | 0.441 | |

| GPMCL-AlexNet | 0.897 | 0.818 | 0.530 | |

| GPMCL-VGG19 | 0.913 | 0.839 | 0.552 | |

| GPMCL-1 | 0.925 | 0.836 | 0.610 | |

| GPMCL-2 | 0.829 | 0.724 | 0.577 | |

| GPMCL-2(a) | 0.823 | 0.634 | 0.570 | |

| GPMCL-2(b) | 0.918 | 0.833 | 0.585 | |

| GPMCL-3 | 0.936 | 0.848 | 0.614 | |

| GPMCL-4 | 0.925 | 0.836 | 0.592 | |

| T2I | GPMCL | 0.907 | 0.837 | 0.664 |

| JDSH(AlexNet) | 0.878 | 0.794 | 0.632 | |

| DGCPN(VGG19) | 0.875 | 0.783 | 0.632 | |

| GPMCL-AlexNet | 0.877 | 0.816 | 0.643 | |

| GPMCL-VGG19 | 0.897 | 0.821 | 0.637 | |

| GPMCL-1 | 0.897 | 0.825 | 0.659 | |

| GPMCL-2 | 0.841 | 0.704 | 0.608 | |

| GPMCL-2(a) | 0.845 | 0.604 | 0.589 | |

| GPMCL-2(b) | 0.891 | 0.793 | 0.629 | |

| GPMCL-3 | 0.905 | 0.832 | 0.661 | |

| GPMCL-4 | 0.886 | 0.814 | 0.619 |

| Method | Backbone | MIR-Flickr-25K | NUS-WIDE | Wiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJSRH [21] | AlexNet + MLP | 145.8 | 144.2 | 140.1 |

| JDSH [23] | AlexNet + MLP | 145.8 | 144.2 | 140.1 |

| DSAH [24] | AlexNet + MLP | 144.5 | 146.1 | 140.4 |

| DGCPN [22] | VGG19 + MLP | 160.9 | 162.6 | 156.9 |

| PDDH [8] | VGG19 + MLP | 146.1 | 144.5 | 140.4 |

| GPMCL | CLIP + MLP | 152.6 | 152.0 | 150.5 |

| Dataset | Index Time (ms) | I → T Latency (ms/Query) | T → I Latency (ms/Query) | DB Storage (KB) | Query Storage (KB) | Samples (DB/Query) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR-Flickr-25K | 2.00 | 0.5399 | 0.5710 | 4505.60 | 500.00 | 18,015/2000 |

| NUS-WIDE | 25.02 | 0.7598 | 0.7370 | 46,131.20 | 500.00 | 184,577/2000 |

| Wiki | 0.01 | 0.1528 | 0.1551 | 543.25 | 173.25 | 2173/693 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Shi, G. Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010389

Zhao Y, Shi G. Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010389

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yan, and Guohua Shi. 2026. "Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010389

APA StyleZhao, Y., & Shi, G. (2026). Graph-Propagated Multi-Scale Hashing with Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Cross-Modal Retrieval. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010389